Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Weather front

View on Wikipedia

|

| Meteorology |

|---|

| Climatology |

| Aeronomy |

| Glossaries |

A weather front is a boundary separating air masses for which several characteristics differ, such as air density, wind, temperature, and humidity. Disturbed and unstable weather due to these differences often arises along the boundary. For instance, cold fronts can bring bands of thunderstorms and cumulonimbus precipitation or be preceded by squall lines, while warm fronts are usually preceded by stratiform precipitation and fog. In summer, subtler humidity gradients known as dry lines can trigger severe weather. Some fronts produce no precipitation and little cloudiness, although there is invariably a wind shift.[1]

Cold fronts generally move from west to east, whereas warm fronts move poleward, although any direction is possible. Occluded fronts are a hybrid merge of the two, and stationary fronts are stalled in their motion. Cold fronts and cold occlusions move faster than warm fronts and warm occlusions because the dense air behind them can lift as well as push the warmer air. Mountains and bodies of water can affect the movement and properties of fronts, other than atmospheric conditions.[2] When the density contrast has diminished between the air masses, for instance after flowing out over a uniformly warm ocean, the front can degenerate into a mere line which separates regions of differing wind velocity known as a shear line. This is most common over the open ocean.

Bergeron classification of air masses

[edit]The Bergeron classification is the most widely accepted form of air mass classification. Air mass classifications are indicated by three letters:[3][4] Fronts separate air masses of different types or origins, and are located along troughs of lower pressure.[5]

- The first letter describes its moisture properties, with

- c used for continental air masses (dry) and

- m used for maritime air masses (moist).

- The second letter describes the thermal characteristic of its source region:

- The third letter designates the stability of the atmosphere; it is labeled:

- k if the air mass is colder (“kolder”) than the ground below it.

- w if the air mass is warmer than the ground below it.

Surface weather analysis

[edit]

2. warm front

3. stationary front

4. occluded front

5. surface trough

6. squall / shear line

7. dry line

8. tropical wave

9. trough

A surface weather analysis is a special type of weather map which provides a top view of weather elements over a geographical area at a specified time based on information from ground-based weather stations.[6] Weather maps are created by detecting, plotting and tracing the values of relevant quantities such as sea-level pressure, temperature, and cloud cover onto a geographical map to help find synoptic scale features such as weather fronts.[7] Surface weather analyses have special symbols which show frontal systems, cloud cover, precipitation, or other important information. For example, an H may represent a high pressure area, implying fair or clear weather. An L on the other hand may represent low pressure, which frequently accompanies precipitation and storms. Low pressure also creates surface winds deriving from high pressure zones and vice versa. Various symbols are used not just for frontal zones and other surface boundaries on weather maps, but also to depict the present weather at various locations on the weather map. In addition, areas of precipitation help determine the frontal type and location.[6]

Types

[edit]There are two different meanings used within meteorology to describe weather around a frontal zone. The term "anafront" describes boundaries which show instability, meaning air rises rapidly along and over the boundary to cause significant weather changes and heavy precipitation. A "katafront" is weaker, bringing smaller changes in temperature and moisture, as well as limited rainfall.[8]

Cold front

[edit]A cold front is located along and on the bounds of the warm side of a tightly packed temperature gradient. On surface analysis charts, this temperature gradient is visible in isotherms and can sometimes also be identified using isobars since cold fronts often align with a surface trough. On weather maps, the surface position of the cold front is marked by a blue line with triangles pointing in the direction where cold air travels and it is placed at the leading edge of the cooler air mass.[2] Cold fronts often bring rain, and sometimes heavy thunderstorms as well. Cold fronts can produce sharper and more intense changes in weather and move at a rate that is up to twice as fast as warm fronts, since cold air is more dense than warm air, lifting as well as pushing the warm air preceding the boundary. The lifting motion often creates a narrow line of showers and thunderstorms if enough humidity is present as the lifted moist warm air condenses. The concept of colder, dense air "wedging" under the less dense warmer air is too simplistic,[9] as the upward motion is really part of a maintenance process for geostrophic balance on the rotating Earth in response to frontogenesis.

Warm front

[edit]Warm fronts are at the leading edge of a homogeneous advancing warm air mass, which is located on the equatorward edge of the gradient in isotherms, and lie within broader troughs of low pressure than cold fronts. A warm front moves more slowly than the cold front which usually follows because cold air is denser and harder to lift from the Earth's surface.[2]

This also forces temperature differences across warm fronts to be broader in scale. Clouds appearing ahead of the warm front are mostly stratiform, and rainfall more gradually increases as the front approaches. Fog can also occur preceding a warm frontal passage. Clearing and warming is usually rapid after frontal passage. If the warm air mass is unstable, thunderstorms may be embedded among the stratiform clouds ahead of the front, and after frontal passage thundershowers may still continue. On weather maps, the surface location of a warm front is marked with a red line of semicircles pointing in the direction the air mass is travelling.[2]

Occluded front

[edit]

An occluded front is formed when a cold front overtakes a warm front,[10] and usually forms around mature low-pressure areas, including cyclones.[2] The cold and warm fronts curve naturally poleward into the point of occlusion, which is also known as the triple point.[11] It lies within a sharp trough, but the air mass behind the boundary can be either warm or cold. In a cold occlusion, the air mass overtaking the warm front is cooler than the cold air mass receding from the warm front and plows under both air masses. In a warm occlusion, the cold air mass overtaking the warm front is warmer than the cold air mass receding from the warm front and rides over the colder air while lifting the warm air.[2]

A wide variety of weather can be found along an occluded front, with thunderstorms possible, but usually their passage is also associated with a drying of the air mass. Within the occlusion of the front, a circulation of air brings warm air upward and sends drafts of cold air downward, or vice versa depending on the type of occlusion the front is experiencing. Precipitations and clouds are associated with the trowal, the projection on the Earth's surface of the tongue of warm air aloft formed during the occlusion process of the depression or storm.[12]

Occluded fronts are indicated on a weather map by a purple line with alternating half-circles and triangles pointing in direction of travel.[2] The trowal is indicated by a series of blue and red junction lines.

Warm sector

[edit]The warm sector is a near-surface air mass in between the warm front and the cold front, usually found on the equatorward side of an extratropical cyclone. With its warm and humid characteristics, this air is susceptive to convective instability and can sustain thunderstorms, especially if lifted by the advancing cold front.

Stationary front

[edit]A stationary front is a non-moving (or stalled) boundary between two air masses, neither of which is strong enough to replace the other. They tend to remain essentially in the same area for extended periods of time, especially with parallel winds directions;[13] They usually move in waves but not persistently.[14] There is normally a broad temperature gradient behind the boundary with more widely spaced isotherm packing.

A wide variety of weather can be found along a stationary front, but usually clouds and prolonged precipitation are found there. Stationary fronts either dissipate after several days or devolve into shear lines, but they can transform into a cold or warm front if the conditions aloft change. Stationary fronts are marked on weather maps with alternating red half-circles and blue spikes pointing opposite to each other, indicating no significant movement.

When stationary fronts become smaller in scale and stabilizes in temperature, degenerating to a narrow zone where wind direction changes significantly over a relatively short distance, they become known as shearlines.[15] A shearline is depicted as a line of red dots and dashes.[2] Stationary fronts may bring light snow or rain for a long period of time.

Dry line

[edit]A similar phenomenon to a weather front is the dry line, which is the boundary between air masses with significant moisture differences instead of temperature. When the westerlies increase on the north side of surface highs, areas of lowered pressure will form downwind of north–south oriented mountain chains, leading to the formation of a lee trough. Near the surface during daylight hours, warm moist air is denser than dry air of greater temperature, and thus the warm moist air wedges under the drier air like a cold front. At higher altitudes, the warm moist air is less dense than the cooler dry air and the boundary slope reverses. In the vicinity of the reversal aloft, severe weather is possible, especially when an occlusion or triple point is formed with a cold front.[16] A weaker form of the dry line seen more commonly is the lee trough, which displays weaker differences in moisture. When moisture pools along the boundary during the warm season, it can be the focus of diurnal thunderstorms.[17]

The dry line may occur anywhere on earth in regions intermediate between desert areas and warm seas. The southern plains west of the Mississippi River in the United States are a particularly favored location. The dry line normally moves eastward during the day and westward at night. A dry line is depicted on National Weather Service (NWS) surface analyses as an orange line with scallops facing into the moist sector. Dry lines are one of the few surface fronts where the pips indicated do not necessarily reflect the direction of motion.[18]

Squall line

[edit]

Organized areas of thunderstorm activity not only reinforce pre-existing frontal zones, but can outrun actively existing cold fronts in a pattern where the upper level jet splits apart into two streams, with the resultant Mesoscale Convective System (MCS) forming at the point of the upper level split in the wind pattern running southeast into the warm sector parallel to low-level thickness lines. When the convection is strong and linear or curved, the MCS is called a squall line, with the feature placed at the leading edge of the significant wind shift and pressure rise.[19] Even weaker and less organized areas of thunderstorms lead to locally cooler air and higher pressures, and outflow boundaries exist ahead of this type of activity, which can act as foci for additional thunderstorm activity later in the day.[20]

These features are often depicted in the warm season across the United States on surface analyses and lie within surface troughs. If outflow boundaries or squall lines form over arid regions, a haboob may result.[21] Squall lines are depicted on NWS surface analyses as an alternating pattern of two red dots and a dash labelled SQLN or squal line, while outflow boundaries are depicted as troughs with a label of outflow boundary.

Precipitation produced

[edit]

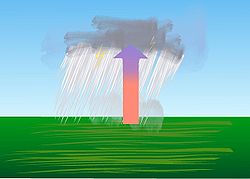

Fronts are the principal cause of significant weather. Convective precipitation (showers, thundershowers, heavy rain and related unstable weather) is caused by air being lifted and condensing into clouds by the movement of the cold front or cold occlusion under a mass of warmer, moist air. If the temperature differences of the two air masses involved are large and the turbulence is extreme because of wind shear and the presence of a strong jet stream, "roll clouds" and tornadoes may occur.[22]

In the warm season, lee troughs, breezes, outflow boundaries and occlusions can lead to convection if enough moisture is available. Orographic precipitation is precipitation created through the lifting action of air due to air masses moving over terrain such as mountains and hills, which is most common behind cold fronts that move into mountainous areas. It may sometimes occur in advance of warm fronts moving northward to the east of mountainous terrain. However, precipitation along warm fronts is relatively steady, as in light rain or drizzle. Fog, sometimes extensive and dense, often occurs in pre-warm-frontal areas.[23] Although, not all fronts produce precipitation or even clouds because moisture must be present in the air mass which is being lifted.[1]

Movement

[edit]Fronts are generally guided by winds aloft, but do not move as quickly. Cold fronts and occluded fronts in the Northern Hemisphere usually travel from the northwest to southeast, while warm fronts move more poleward with time. In the Northern Hemisphere a warm front moves from southwest to northeast. In the Southern Hemisphere, the reverse is true; a cold or occluded front usually moves from southwest to northeast, and a warm front moves from northwest to southeast. Movement is largely caused by the pressure gradient force (horizontal differences in atmospheric pressure) and the Coriolis effect, which is caused by Earth's spinning about its axis. Frontal zones can be slowed by geographic features like mountains and large bodies of warm water.[2]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Miller, Samuel T. (10 November 2000). "Clouds and precipitation". STEC 521 lecture notes. Durham, NH: University of New Hampshire. Archived from the original on 11 January 2005. Retrieved 8 July 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Roth, David (21 November 2013). Unified Surface Analysis Manual (PDF) (Report) (vers. 1 ed.). Honolulu, HI: NOAA / Hydrometeorological Prediction Center / National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 22 October 2006.

- ^ "Airmass classification". Glossary of Meteorology. Retrieved 22 May 2008 – via amsglossary.allenpress.com.

- ^ Saravanan, K.J., ed. (27 June 2008). "Bergeron classification of air masses". weatherfront.blogspot.com. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ Ahrens, C. Donald (2007). Meteorology Today: An introduction to weather, climate, and the environment. Cengage Learning. p. 296. ISBN 978-0-495-01162-0.

- ^ a b Monmonier, Mark S. (1999). Air Apparent: How meteorologists learned to map, predict, and dramatize weather. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-53422-7.

- ^ "Mixed surface analysis". Weather Underground (wunderground.com). Current weather maps. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ Park, Chris C. (2001). The Environment: Principles and applications. Psychology Press. p. 309. ISBN 978-0-415-21771-2.

- ^ "Overrunning". [letter] 'O'. Glossary. NOAA / National Weather Service. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ "Occluded front". Glossary – Weather World 2010 Project. Online guide. Department of Atmospheric Sciences. University of Illinois. Retrieved 22 October 2006.

- ^ "Triple Point". Norman, OK: NOAA / National Weather Service. Retrieved 22 October 2006.

- ^ "Trowal". English glossary. World Meteorological Organisation / Eumetcal. Archived from the original on 31 March 2014. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- ^ "Stationary Front". SKYbrary Aviation Safety. 20 July 2021. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ "Stationary front". Glossary – Weather World 2010 Project. Online guide. Department of Atmospheric Sciences. University of Illinois. Retrieved 22 October 2006.

- ^ "Shear line". Glossary of Meteorology. American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 14 March 2007. Retrieved 22 October 2006 – via amsglossary.allenpress.com.

- ^ Cai, Huaqing. "Dryline cross section". Archived from the original on 20 January 2008. Retrieved 5 December 2006.

- ^ "Lee trough". Glossary of Meteorology. American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 19 September 2011. Retrieved 22 October 2006 – via amsglossary.allenpress.com.

- ^ "Dry line: A moisture boundary". Glossary – Weather World 2010 Project. Online guide. Department of Atmospheric Sciences. University of Illinois. Retrieved 22 October 2006.

- ^ "Chapter 2: Definitions" (PDF). Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorological Services and Supporting Research. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 May 2009. Retrieved 22 October 2006.

- ^ Branick, Michael. "[letter] 'O'". A Comprehensive Glossary of Weather (Report). American Meteorological Society. Retrieved 22 October 2006 – via geographic.org.

- ^ "Haboob". Glossary. American Meteorological Society. 8 June 2016.

- ^ "Convection". Glossary of Meteorology. American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 5 March 2007. Retrieved 22 October 2006 – via amsglossary.allenpress.com.

- ^ "Orographic lifting". Glossary of Meteorology. American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 14 October 2006. Retrieved 22 October 2006 – via amsglossary.allenpress.com.

Further reading

[edit]- Monmonier, Mark S. (1999). Air Apparent: How meteorologists learned to map, predict, and dramatize weather. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-53422-7.

External links

[edit]- Roth, David (21 November 2013). Unified Surface Analysis Manual (PDF) (Report) (vers. 1 ed.). Honolulu, HI: NOAA / Hydrometeorological Prediction Center / National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 22 October 2006.

- "Cold fronts". Glossary – Weather World 2010 Project. Online guide. Department of Atmospheric Sciences. Urbana-Champaign, IL: University of Illinois.

- "Warm fronts". Glossary – Weather World 2010 Project. Online guide. Department of Atmospheric Sciences. Urbana-Champaign, IL: University of Illinois.

- "Fronts: The boundaries between air masses". Glossary – Weather World 2010 Project. Online guide. Department of Atmospheric Sciences. Urbana-Champaign, IL: University of Illinois.

Weather front

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Characteristics

A weather front is defined as a boundary or transition zone between two distinct air masses that differ in temperature, humidity, and density.[6] These air masses originate from different source regions, leading to sharp contrasts across the front, such as cooler, denser air abutting warmer, moister air.[1] The interface represents a narrow region where properties like temperature and dew point change abruptly over relatively short horizontal distances.[7] Key characteristics of weather fronts include their limited width, typically spanning 50-200 kilometers horizontally, forming a steep, sloping interface between the air masses.[1] This slope arises because the lighter, warmer air overrides the denser, cooler air, creating a tilted boundary that extends vertically for several kilometers before dissipating aloft, often between 2 and 4 kilometers in elevation.[8] Fronts are commonly associated with pressure troughs, where surface pressures dip due to the convergence of air from adjacent high-pressure systems, and they exhibit zones of convergence that enhance upward motion at the boundary.[7][8] In weather systems, fronts play a crucial role as triggers for cyclogenesis, the development of low-pressure centers, by promoting low-level convergence and vertical ascent.[1] They drive cloud formation through buoyancy-driven lifting, where warmer air rises over cooler air, often resulting in layered or convective clouds and sharp weather contrasts like temperature drops or wind shifts.[1] Mid-latitude fronts, for example, can extend horizontally for hundreds of kilometers, influencing synoptic-scale weather patterns across continents.[7]Historical Development

The concept of weather fronts emerged in the early 20th century amid efforts to improve military weather forecasting during World War I. In 1918, Norwegian physicist Vilhelm Bjerknes, tasked with establishing a forecasting service for the Norwegian military, began analyzing surface weather observations and identified sharp boundaries between contrasting air masses, which he termed "fronts" in analogy to the battlefronts of the war.[9] His work from 1918 to 1919 emphasized the interactions between polar (cold) and tropical (warm) air masses as key drivers of cyclonic activity, laying the groundwork for systematic front analysis.[10] This approach was initially applied in an experimental forecasting service at the Bergen Geophysical Institute, producing daily predictions starting in 1918.[10] The Bergen School, founded by Vilhelm Bjerknes in 1917 and active through the early 1920s, advanced these ideas into a comprehensive frontal cyclone model under the leadership of his son Jacob Bjerknes, along with Halvor Solberg and Tor Bergeron. Jacob Bjerknes' 1919 paper, "On the Structure of Moving Cyclones," introduced the notion of distinct warm and cold sectors separated by frontal discontinuities, formalizing the lifecycle of extratropical cyclones.[10] Building on this, the team developed the concepts of cold fronts (advancing cold air displacing warmer air), warm fronts (warm air overriding cooler air), and occluded fronts (where a cold front overtakes a warm front, lifting the warm sector aloft), as detailed in their collaborative analyses. A key milestone was the 1921 publication by Jacob Bjerknes and Halvor Solberg in Geofysiska Publikationer, titled "Meteorological Conditions for the Formation of Rain," which synthesized the Norwegian model and explained precipitation patterns along fronts.[12] Tor Bergeron further refined the occlusion process by 1922, highlighting its role in cyclone maturity. Following World War II, the frontal model integrated with expanding upper-air observations, enabling three-dimensional analysis of atmospheric dynamics. In the United States, adoption accelerated in the 1940s through military meteorology programs, where Swedish émigré Carl-Gustaf Rossby trained thousands of forecasters at the University of Chicago's Institute of Meteorology, incorporating Norwegian methods into wartime aviation forecasting using pilot-collected data.[13] By the 1950s, these foundations supported the advent of numerical weather prediction (NWP), with early experiments on the ENIAC computer in 1950 applying frontal principles to model cyclone evolution, marking a shift toward computational verification of the Norwegian concepts.[14]Air Masses and Formation

Air Mass Classification

Air masses are large bodies of air with relatively uniform temperature and humidity characteristics, acquired from their source regions, and serve as the foundational components for weather fronts, which form at their boundaries.[2] The classification system, developed by Tor Bergeron in his seminal 1928 work on synoptic analysis, categorizes these air masses based on their latitude of origin (affecting temperature) and surface type (affecting moisture content), using a three-letter code to denote these attributes.[15] This system emphasizes the horizontal uniformity of properties within an air mass, enabling meteorologists to predict weather patterns from contrasts between them.[16] The first letter in the code indicates moisture: "c" for continental (dry air forming over land surfaces) or "m" for maritime (moist air forming over oceans).[2] The second letter denotes temperature based on latitude: "P" for polar (cold air from higher latitudes, typically 50°–70° N/S), "T" for tropical (warm air from lower latitudes, around 20°–30° N/S), or "A" for arctic (extremely cold air from polar ice caps, as a variant of polar).[2] The optional third letter, if present (k for cold or w for warm), further specifies vertical stability, though it is less commonly used in basic classifications.[17]| Code | Type | Source Region Example | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| cA | Continental Arctic | Arctic ice caps (e.g., Greenland) | Extremely cold, very dry, highly stable |

| cP | Continental Polar | High-latitude land (e.g., Siberia) | Cold, dry, stable |

| mP | Maritime Polar | Subpolar oceans (e.g., North Atlantic) | Cool, moist, conditionally unstable |

| cT | Continental Tropical | Deserts (e.g., Sahara) | Hot, dry, unstable near surface |

| mT | Maritime Tropical | Subtropical oceans (e.g., Gulf of Mexico) | Warm, very moist, unstable |

Mechanisms of Front Formation

Weather fronts develop primarily through the process of frontogenesis, which tightens horizontal temperature gradients via the advection of contrasting air masses toward a common boundary, resulting in deformation and convergence that sharpens the thermal contrast.[18] This kinematic forcing arises from large-scale atmospheric circulations that bring dissimilar air masses, such as dry continental polar (cP) and moist maritime tropical (mT), into juxtaposition, where differential velocities along the interface promote shearing and confluence.[18] The deformation field, characterized by stretching in one direction and compression in the perpendicular direction, acts as the core mechanism, converting broad baroclinic zones into narrow frontal discontinuities over scales of hours to days.[19] In the context of extratropical cyclones, fronts emerge as integral components of the cyclone's structure, driven by the cyclone's rotation and associated conveyor belts that organize air mass interactions.[20] The warm conveyor belt, a broad stream of ascending warm, moist air rising ahead of the warm front, contrasts with the cold air outbreak behind the cold front, where dense polar air surges equatorward, reinforcing the frontal boundary through sustained advection and convergence.[20] This cyclonic organization, first conceptualized in the Norwegian cyclone model, positions fronts along the cyclone's leading edges, where the interplay of these conveyor belts amplifies temperature gradients and sustains frontogenesis throughout the cyclone lifecycle.[20] The sloping nature of frontal surfaces, with a typical tilt ratio of 1:50 to 1:100 (horizontal distance to vertical rise), results from the buoyancy differences between air masses, leading to the denser cold air wedging under the warmer air and inducing forced ascent along the inclined boundary.[21] This geometry ensures that uplift occurs over a broad horizontal extent, particularly pronounced in cold fronts, where the steeper slope promotes rapid vertical motion and associated weather phenomena like precipitation bands.[21] Secondary mechanisms, including upper-level jet streams and vorticity advection, further enhance surface frontogenesis by generating ageostrophic circulations that concentrate isentropes and intensify baroclinicity.[22] Jet streaks aloft, often aligned parallel to surface fronts, produce divergence in their exit regions, promoting subsidence that sharpens upper-level thermal gradients, while positive vorticity advection downstream reinforces the low-level convergence essential for boundary maintenance.[22] These upper-level dynamics couple with surface processes, amplifying the overall frontogenetic forcing in baroclinic environments.[22]Analysis and Detection

Surface Weather Maps

Surface weather maps, also known as surface analysis charts, serve as the primary tool for manually identifying and depicting weather fronts through the plotting and interpretation of ground-based observations. These charts integrate data from weather stations, including temperature, dew point, wind direction and speed, and sea-level pressure, to reveal discontinuities that signify frontal boundaries. Fronts appear as lines connecting points of abrupt changes, often aligned with pressure troughs where isobars kink or bend sharply, reflecting the denser air mass overriding or undercutting the lighter one. Key symbols on these maps standardize the representation of fronts for consistent analysis. Cold fronts are depicted by a solid blue line with triangular "teeth" pointing in the direction of movement, indicating the advancing colder air mass. Warm fronts are shown as a solid red line with semicircular symbols on the side toward which the front is advancing, signifying the warmer air mass displacing cooler air. Occluded fronts use a purple line combining alternating triangles and semicircles, pointing toward the direction of motion to illustrate the complex lifting of the warm air sector. These conventions, established by the World Meteorological Organization, ensure global uniformity in frontal depiction. Manual interpretation of surface maps involves plotting station data, such as from METAR reports, onto a base chart to identify gradients. Analysts locate fronts along the axis of maximum temperature and dew point contrasts, typically where changes exceed 5°C (9°F) over 100 km (62 miles), often coinciding with wind shifts from southerly to westerly or northerly directions across the boundary. Pressure troughs, marked by converging isobars, guide front placement, as fronts rarely cross them; instead, they align parallel or along these features due to the baroclinic zone formed by air mass contrasts. This process requires evaluating multiple variables simultaneously to confirm a front's position, avoiding false identifications from local terrain effects. Historically, surface weather mapping relied on teletype networks from the 1940s to the 1980s, where automated weather observations were transmitted via Morse code or teletype to central offices for manual plotting on large charts. Organizations like the U.S. Weather Bureau used these real-time feeds to produce hourly or six-hourly analyses, enabling forecasters to track frontal movements across continents. This labor-intensive method laid the groundwork for modern automated systems while emphasizing the skill in recognizing subtle frontal signatures.Remote Sensing and Modeling

Remote sensing techniques have revolutionized the detection of weather fronts by providing three-dimensional views of atmospheric structures that surface observations alone cannot capture. Satellites, such as the Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite (GOES) series operated by NOAA and the Meteosat series by EUMETSAT, utilize visible and infrared imagery to identify cloud bands associated with frontal boundaries. Visible imagery highlights thicker cloud formations during daylight hours, revealing elongated cloud streets or bands that delineate warm and cold fronts, while infrared channels detect cloud-top temperatures, distinguishing high-altitude cirrus clouds ahead of warm fronts from lower, warmer cumuliform clouds behind cold fronts.[23][24] Water vapor channels on these satellites further enhance upper-level front detection by tracing moisture gradients in the mid- to upper troposphere, where dry air intrusions signal the position of jet streams and associated upper fronts. For instance, Meteosat's Spinning Enhanced Visible and Infrared Imager (SEVIRI) captures water vapor imagery every 15 minutes, allowing meteorologists to visualize the transport of air masses and the structure of upper-level fronts influencing surface weather patterns. GOES satellites similarly employ water vapor bands to monitor these features over the Americas, aiding in the identification of frontal waves and occlusion processes aloft.[25][23] Ground-based remote sensing complements satellite data through Doppler radar and wind profilers, which probe the lower atmosphere for frontal signatures. Doppler weather radars, part of networks like the U.S. NEXRAD system, detect precipitation echoes aligned along frontal boundaries, such as the narrow lines of intense rain or snow marking cold fronts, and reveal velocity shifts indicating wind convergence or divergence across the front. These radars measure radial velocities to quantify the speed and direction of hydrometeors, enabling the tracking of frontal propagation over ranges up to 250 km. Wind profilers, operating in the VHF or UHF bands, provide vertical wind profiles from the surface to 16 km, capturing shear layers and low-level jets that characterize the vertical structure of fronts, particularly during high-impact events like frontal passages in the planetary boundary layer.[26][27] Numerical weather prediction models integrate these remote sensing inputs for automated frontal diagnosis, employing diagnostics like potential vorticity (PV) and thermal gradients to delineate fronts objectively. In the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) Integrated Forecasting System, PV anomalies at levels like 300 hPa highlight dynamic tropopause folds associated with upper fronts, while gradients in 850 hPa wet-bulb potential temperature identify surface air mass boundaries and frontal zones. The Global Forecast System (GFS) from NOAA similarly uses thermal frontogenesis parameters, derived from temperature advection and deformation fields, to locate regions of concentrated baroclinicity indicative of fronts. Automated front-finding algorithms, such as the FrontFinder AI developed for high-resolution model outputs, apply machine learning to detect gradients in thermodynamic variables like equivalent potential temperature and wind shifts, classifying cold, warm, stationary, and occluded fronts with high accuracy over continental scales.[28][29][30] For short-term forecasting, or nowcasting, ensemble modeling assimilates remote sensing data to predict frontal evolution over 0-6 hours. ECMWF's ensemble vertical profile products blend satellite and profiler observations to forecast wind shear and moisture layers across fronts, with multiple members capturing uncertainty in frontal speed and intensity, as seen in analyses of Antarctic frontal systems. Similarly, the GFS ensemble incorporates radar-derived precipitation nowcasts to refine frontal boundary positions, enabling probabilistic guidance on the timing of frontal passages and associated weather hazards. These integrated approaches improve lead times for severe weather alerts by quantifying the range of possible frontal trajectories.[31][32]Types of Fronts

Cold Fronts

A cold front represents the leading boundary of a cooler, denser air mass advancing into and displacing a warmer air mass, characterized by a steep slope typically ranging from 1:50 to 1:100, which promotes abrupt uplift of the warm air ahead of the front.[33][21] This steep inclination, often steepest in the lowest several hundred meters of the atmosphere, results in the cold air undercutting the warmer air, forcing it to rise rapidly over a narrow zone usually 5 to 50 kilometers wide.[34][35] The frontal surface's narrow width concentrates the temperature gradient, leading to intense vertical motion and dynamic instability along the boundary.[36] The weather associated with cold fronts is often vigorous and short-duration, featuring intense showers, squall lines, and thunderstorms due to the rapid lifting and cooling of moist warm air, which can generate cumulonimbus clouds and severe convective activity.[1][37] These phenomena typically occur along or just ahead of the front, with squalls producing strong, gusty winds exceeding 50 km/h and heavy precipitation in narrow bands.[38] Following the front's passage, post-frontal conditions bring clearing skies as sinking air in the cold sector evaporates clouds, accompanied by persistent gusty winds from the northwest in the Northern Hemisphere, reflecting the dense air's advection.[34][38] In mid-latitudes, cold fronts generally propagate from west to east at speeds of 20 to 40 km/h, driven by the prevailing westerly winds and the cyclone's circulation, though rates can vary with the season and synoptic setup.[39] Diurnal variations may influence movement, with fronts sometimes accelerating during daytime heating or slowing under nocturnal stability.[34] A representative example is spring cold fronts in the Midwest United States, where advancing cold air from Canada clashes with warm, humid Gulf air, frequently triggering severe thunderstorms, tornadoes, and hail during events like the April 2025 outbreak across Nebraska and Iowa.[40][41]Warm Fronts

A warm front represents the leading edge of an advancing warm air mass that gradually overrides a retreating mass of cooler air, creating a boundary characterized by a gentle slope due to the lower density of the warm air. This structure typically features a slope ratio of approximately 1:150 to 1:200, which facilitates the slow ascent of warm air over the denser cold air beneath, resulting in a broad transition zone spanning 200–300 km.[17][42] The gentle incline promotes layered cloud formation rather than abrupt lifting, distinguishing warm fronts from steeper boundaries. As the warm front approaches, a characteristic progression of clouds develops, beginning with high-level cirrus clouds appearing 500–1000 km ahead, transitioning to cirrostratus and altostratus, and culminating in low-level nimbostratus or stratus clouds near the front, often accompanied by fog. This leads to prolonged periods of light to moderate precipitation, including drizzle or steady rain, extending 200–400 km ahead of the front in a wide belt, with conditions improving to clearer skies and warmer temperatures after passage. Visibility may be reduced due to haze or fog in the warm sector, but severe weather is uncommon.[1][42][17] Warm fronts generally move more slowly than other frontal types, advancing at speeds of 15–40 km/h (10–25 mph), influenced by the upper-level winds and the resistance of the denser cold air. In the Northern Hemisphere, they often progress northeastward, associated with the warm sector of mid-latitude cyclones. For instance, in Europe, warm fronts ahead of low-pressure systems originating from the Atlantic frequently bring extended overcast conditions and persistent light rain across regions like the British Isles and northwestern continent.[43][2] These fronts arise from contrasts between moist, warm air masses (such as maritime tropical) and cooler ones (like continental polar).[38]Occluded Fronts

An occluded front forms when a faster-moving cold front overtakes a slower-moving warm front within an extratropical cyclone, lifting the warmer air mass in the intervening sector aloft and separating it from the surface low-pressure center.[44] This process typically occurs during the mature stage of cyclone development, as described in the Norwegian cyclone model, where the cold front "catches up" to the warm front.[45] There are two primary types: a cold occlusion, in which the air mass behind the overtaking cold front is colder than the air mass ahead of the warm front, causing the cold front to undercut both; and a warm occlusion, where the air behind the cold front is warmer than the air ahead, leading the cold front to ride over the cooler air mass.[44] The structure of an occluded front features a triple point, the junction where the cold front, warm front, and occluded front converge, often marking the point of most intense weather activity near the cyclone's center.[46] In mature extratropical cyclones, particularly those over oceanic regions, a bent-back occlusion may develop, where the frontal boundary wraps westward and around the low center, forming a hook-like extension that isolates the warm core aloft.[47] This configuration enhances the cyclone's intensity temporarily before decay sets in, with the occluded front appearing as a hybrid boundary blending elements of both parent fronts. Weather patterns along occluded fronts include widespread stratiform clouds and precipitation, often transitioning from the steady rain of a warm front ahead to clearer, cooler conditions behind, though with lingering moisture.[44] In winter scenarios, mixed precipitation is common, with rain falling on the warmer side and snow on the colder side, accompanied by wrapped cloud bands that spiral around the cyclone.[8] These fronts generally produce less severe weather than active cold or warm fronts, signaling the cyclone's weakening phase, though embedded bands of heavier rain or snow can occur parallel to the boundary.[44] Prominent examples of occluded fronts appear in North Atlantic winter cyclones, where the occlusion process often drives the storm's evolution and impacts. For instance, during the January 2007 Storm Kyrill, a mature cyclone crossing from the North Atlantic into Europe developed an occluded front that facilitated secondary cyclogenesis, leading to intense precipitation and winds exceeding 100 km/h across the region.[48] Similarly, observational studies of North Atlantic cyclones have documented cold-type occlusions forming rearward-sloping structures, contributing to prolonged cloud and precipitation bands in mid-latitude winter storms.[49]Stationary Fronts

A stationary front forms when the boundary between two dissimilar air masses exhibits little to no net movement, typically due to opposing winds parallel to the front or weak pressure gradients that balance the forces between the air masses.[38][50] This occurs when neither the warmer air mass to the south nor the cooler air mass to the north can displace the other, often as a cold or warm front slows and stalls.[43] Such fronts are identified on weather maps by alternating red semicircles and blue triangles pointing in opposite directions along the line, indicating the stalled position.[50] The structure of a stationary front is characterized by a meandering boundary that remains largely in place, with minimal perpendicular displacement over observation periods of three to six hours.[51][50] These fronts can persist for days to weeks, depending on the stability of the atmospheric conditions, leading to extended influences on local weather without rapid evolution.[52][53] If the force balance shifts—such as through changes in wind patterns or pressure—one air mass may gain dominance, causing the front to transition into a moving cold or warm front.[43] Weather associated with stationary fronts includes persistent low-level clouds and scattered showers along the boundary, driven by convergence and gentle lifting of moist air.[38] In humid environments, fog can develop, especially overnight or in valleys, due to the stable, moist conditions near the surface.[38] For instance, summer stalls over the U.S. East Coast often feature these fronts, resulting in prolonged overcast skies and light precipitation that can disrupt outdoor activities for several days.[50]Drylines and Squall Lines

A dryline is a mesoscale boundary that separates moist maritime air masses from dry continental air masses, primarily occurring in the central and southern Great Plains of the United States.[54] This boundary forms due to the contrast between humid air advected northward from the Gulf of Mexico to the east and arid air originating from the southwestern deserts and Mexican Plateau to the west.[2] Unlike traditional fronts, the dryline features a pronounced moisture gradient with minimal temperature difference, often manifesting as a sharp dewpoint drop of around 10°C per 100 km, though stronger gradients up to 10°C per 1 km can occur in intense cases.[55][56] It typically orients north-south and advances eastward during the afternoon under solar heating, retreating westward at night.[50] The dryline plays a critical role in initiating severe weather, particularly thunderstorms, by providing lift through convergence along the boundary where denser moist air interacts with drier air.[57] Convection often erupts along or just east of the dryline, fueled by the release of instability from the moist sector, leading to supercell thunderstorms and potential tornadoes in the Great Plains region.[56] Squall lines, also known as quasi-linear convective systems, are elongated bands of thunderstorms that develop as linear mesoscale features, frequently along or ahead of boundaries like gust fronts.[58] These systems consist of contiguous or intermittent clusters of convective cells, producing heavy rain and high winds as they propagate.[59] The leading edge of a squall line is often marked by a gust front, a narrow zone of cool, rain-outflow air that acts like a density-driven boundary, forcing uplift of warmer, moist air ahead of it.[60] Squall lines can extend for hundreds of kilometers and move rapidly, typically at speeds of 30-60 km/h.[61] Associated with squall lines are hazardous weather phenomena, including damaging straight-line winds exceeding 90 km/h from downdrafts and microbursts, as well as large hail from intense updrafts within the convective line.[58] These systems contribute to widespread severe weather outbreaks, particularly when embedded in environments with high low-level shear.[62] In contrast to synoptic-scale fronts, which span thousands of kilometers and persist for days to weeks, drylines and squall lines are shorter-lived mesoscale phenomena, lasting from hours to a couple of days, and are predominantly driven by convective processes rather than large-scale advection.[56][61] This mesoscale nature results in more localized but rapidly evolving weather patterns, emphasizing moisture contrasts and boundary-layer dynamics over broader thermal gradients.[55]Dynamics and Movement

Frontal Structure

A weather front's horizontal structure features a narrow core zone where the maximum temperature gradient occurs, typically spanning about 100 km across the front while extending 1000 km or more along it, marking the boundary between distinct air masses with sharp contrasts in temperature, moisture, and density.[63] This core is embedded within a broader transition zone of several hundred kilometers, where gradients gradually diminish away from the front. A key characteristic is the wind reversal across the front, with stronger winds in the cold air mass compared to the warm, resulting in positive geostrophic relative vorticity due to the across-front ageostrophic pressure gradient force.[63] Fronts can be classified as narrowband, with intense, localized gradients over short distances (e.g., 100 km in cold fronts), or broad types, featuring more diffuse transitions over wider areas (e.g., warm fronts with gradients spanning 400 km or more).[63][2] Vertically, fronts exhibit sloping isentropes (surfaces of constant potential temperature) that tilt downward toward the colder air mass, with slopes varying by front type—steeper in cold fronts (around 1:50) and shallower in warm fronts (around 1:150)—leading to enhanced static stability within the frontal zone.[63] Above the surface front, an upper-level front often persists near the tropopause, characterized by a vertical thickness of 1-2 km and a cross-front scale of about 100 km at the level of maximum wind, where temperature gradients, cyclonic shear, and static stability are maximized.[64] In intense cases, such as those associated with strong baroclinic waves, tropopause folding occurs, where stratospheric air subsides into the troposphere along the front, driven by differential potential vorticity advection and reaching depths of 450-700 mb, facilitating stratosphere-troposphere exchange.[64][63] The warm sector represents a distinct zone of relatively homogeneous, warm air sandwiched between an advancing warm front and a trailing cold front in a mature extratropical cyclone, often featuring stable conditions with minimal precipitation and thinning low-level clouds.[17] This sector contrasts with the frontal boundaries, providing a buffer where air mass properties are uniform over hundreds of kilometers. Frontal diagnostics rely on the frontogenesis function, which quantifies the local intensification of the horizontal temperature gradient through combined effects of deformation (stretching and shearing of flow that aligns with isotherms to tighten gradients) and confluence (convergent airflow perpendicular to the front that packs isentropes closer together).[19][63] When deformation and confluence dominate, they enhance the core zone's sharpness, promoting ageostrophic circulations that sustain the front's structure.[19]Speed and Direction

The speed of a weather front is primarily governed by the component of the geostrophic wind in the warm air mass perpendicular to the frontal boundary, which provides the advecting flow that propels the front forward.[17] Additionally, upper-level winds, particularly jet streams, steer the overall trajectory and pace of fronts by influencing the broader synoptic-scale circulation.[65] In theoretical models, the propagation speed of a front approximates the component of the geostrophic wind in the warm sector perpendicular to the front, often expressed as , where is the geostrophic wind speed in the warm air and is the angle between this wind and the frontal orientation.[66] Typical speeds vary by front type, with cold fronts advancing at 40–48 km/h (25–30 mph) due to the denser cold air mass driving more rapid progression, while warm fronts move more slowly at 16–40 km/h (10–25 mph) as the lighter warm air ascends gradually.[67][68] Stationary fronts, by contrast, progress at less than 5 knots (approximately 9 km/h) when opposing winds balance the motion.[34] The direction of frontal movement generally follows the isobars in the cyclone-relative sense, with fronts circulating counterclockwise around low-pressure centers in the Northern Hemisphere, often paralleling the warm-sector flow.[8] Seasonal variations influence this, as winter conditions promote more meridional (north-south) orientations due to amplified temperature gradients and wave patterns in the upper-level flow, whereas summer sees predominantly zonal (west-east) progressions.[69]Weather Effects

Precipitation Patterns

Precipitation associated with weather fronts arises primarily from the forced ascent of moist air along the frontal boundary, where warmer air is lifted over cooler air, promoting condensation and cloud formation. This lifting can be enhanced orographically when fronts interact with terrain, leading to increased rainfall on windward slopes due to additional uplift from the topography. For instance, in regions with steep terrain, such as the Alps, orographic enhancement can amplify precipitation by factors influenced by slope steepness, atmospheric stability, and wind speed, often resulting in localized heavy rain during frontal passages.[70] Frontal precipitation mechanisms differ between convective and stratiform types, with stratiform rain predominant in many systems due to large-scale ascent. The warm conveyor belt (WCB), a key airstream in extratropical cyclones, transports moist air northward and upward over the cold front, producing extensive stratiform clouds and precipitation in the comma head region of the cyclone. This quasi-isentropic ascent, often lasting over 12 hours, combines with the cold conveyor belt to form deep cloud layers and banded rain, particularly in occluded systems. In contrast, convective precipitation occurs more frequently along cold fronts where instability allows for upright development of showers and thunderstorms.[20] Precipitation patterns vary relative to the front's position. Pre-frontal precipitation, often associated with warm fronts, is typically light and widespread, occurring well ahead of the boundary as moist air ascends gradually over a broad area, producing stratus clouds and steady drizzle or rain. At the frontal boundary itself, precipitation intensifies into heavy, banded structures, such as narrow zones of intense rain along cold fronts where uplift is strongest. Post-frontal conditions feature scattered showers, often convective in nature, as cooler air stabilizes the atmosphere but residual moisture supports isolated cells; in colder seasons, this can manifest as snow in the cold sector behind the front, particularly in post-cold frontal environments over elevated terrain.[33][43][71] The intensity of frontal precipitation depends on factors like moisture flux and atmospheric stability. High moisture flux convergence ahead of the front supplies abundant water vapor, fueling heavier rain rates, while low stability promotes convective overturning and enhanced vertical motion. For example, along advancing cold fronts, these conditions can produce over 50 mm of rain in 24 hours in narrow bands, as seen in midlatitude systems where low-level jets amplify moisture transport. Frontal slopes contribute to this ascent, further intensifying precipitation through forced lifting.[72][73] Globally, frontal precipitation is more persistent and voluminous in midlatitudes, where frequent collisions of contrasting air masses along fronts drive a significant portion of annual rainfall, often exceeding 60% of extreme events in some regions. In subtropical zones, such patterns are more sporadic, limited by weaker baroclinicity and dominance of other mechanisms like the intertropical convergence zone, resulting in less consistent frontal rain.[74][75]Temperature and Wind Changes

As a cold front advances, it typically brings a sharp temperature drop due to the replacement of warmer air by denser, cooler air from higher latitudes, often ranging from 5 to 15°C within a few hours.[34] This rapid cooling results from cold air advection, where the influx of colder air displaces the pre-frontal warm air mass, creating a steep thermal gradient along the frontal boundary.[38] Wind patterns at cold fronts feature a backing shift, with winds turning counterclockwise—such as from southwesterly to northwesterly—as the front passes, accompanied by increasing speeds and gusts that can reach 15-25 m/s in the post-frontal zone due to enhanced mixing and pressure gradients.[76] In contrast, warm fronts involve a more gradual temperature rise as warmer air overrides cooler air ahead of the front, with increases of 5-10°C occurring over several hours to a day, modulated by diurnal cycles where daytime heating can amplify the warming effect.[77] Wind shifts at warm fronts are veering, changing clockwise—for instance, from easterly to southerly—reflecting warm air advection that elevates temperatures while maintaining relatively steady pressure.[78] These changes are less abrupt than at cold fronts, with gusts typically milder, under 10-15 m/s, as the sloping frontal surface promotes smoother air mass transition.[1] The underlying mechanisms driving these temperature contrasts and wind shifts stem from baroclinic instability, where horizontal temperature gradients generate potential energy that converts to kinetic energy, intensifying frontal zones through ageostrophic circulations and vertical motion.[79] Advection of distinct air masses—colder and drier behind cold fronts, warmer and often moister ahead of warm fronts—sustains the thermal discontinuities, while turbulent mixing at the boundary enhances local wind variability.[80] A notable example is the "blue norther" in Texas, a severe cold front type where temperatures can plummet by 20°C or more in under an hour, as seen in the historic event of November 11, 1911, with drops exceeding 30°C across the region.[81]Severe Weather Associations

Weather fronts play a critical role in initiating severe thunderstorms, particularly through mechanisms like frontal lifting and convergence along boundaries such as drylines. In frontal lifting, the forced ascent of warm, moist air over a denser cold air mass at a cold front or along a warm front can release convective available potential energy (CAPE), leading to the development of supercell thunderstorms, which are long-lived, rotating storms capable of producing large hail, damaging winds, and tornadoes.[58] Supercells often form when CAPE values exceed 1000 J/kg, providing the buoyancy needed for intense updrafts.[82] Vertical wind shear, the change in wind speed and direction with height, further organizes these storms by tilting updrafts away from downdrafts, sustaining rotation and increasing severe weather potential; shear values of 20-40 knots over low levels (0-6 km) are commonly associated with supercell formation along fronts.[76][83] Drylines, sharp boundaries between moist and dry air masses often found in the central United States, contribute to severe weather outbreaks in the Plains by promoting strong convergence and lift. The density contrast across the dryline causes moist air east of the boundary to rise rapidly, fostering explosive thunderstorm development, including supercells, especially when combined with high CAPE and shear environments.[84] For instance, the 1974 Super Outbreak, which produced over 100 tornadoes, was driven by a powerful cold front interacting with a dryline, amplifying instability and shear across the Midwest and South. Beyond thunderstorms, fronts are linked to other severe hazards. Derechos, widespread windstorms with gusts exceeding 58 mph over hundreds of miles, frequently develop along squall lines embedded in or ahead of cold fronts, where progressive bow echoes form due to rear-inflow jets and system-scale vorticity.[85] Stalled fronts, which remain quasi-stationary for days, can lead to prolonged heavy precipitation and flash flooding by repeatedly drawing in moisture without advecting it away, saturating soils and overwhelming drainage systems.[86] In winter, ice storms often occur ahead of advancing cold fronts when warm, moist air aloft overrides a shallow layer of subfreezing surface air, causing supercooled rain to freeze on contact with ground surfaces and accumulate as glaze ice.[87] These events are particularly hazardous when associated with arctic fronts, where the temperature contrast enhances the warm layer's depth.[88] Globally, polar lows—intense mesoscale cyclones resembling tropical storms—form near arctic fronts during cold air outbreaks over relatively warm sea surfaces, driven by baroclinic instability in polar air masses. These systems, common in the Nordic Seas and Barents Sea during winter, can produce gale-force winds, heavy snow, and rough seas due to the interaction of cold arctic air with oceanic heat and moisture.[89][90]Forecasting and Impacts

Modern Forecasting Techniques

Modern forecasting techniques for weather fronts rely heavily on numerical weather prediction (NWP) models, which simulate the evolution of atmospheric conditions to predict frontal trajectories and associated weather patterns. The European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) employs its Integrated Forecasting System (IFS), a coupled atmospheric-ocean model that resolves frontal structures through high-resolution simulations, enabling accurate tracking of cold, warm, and occluded fronts over medium-range horizons up to 10 days.[91] Similarly, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA) Global Forecast System (GFS), a global NWP model with a horizontal resolution of approximately 13 km, integrates surface and upper-air data to forecast frontal movements, particularly emphasizing synoptic-scale features like pressure gradients and temperature contrasts that define front positions.[92] To address inherent uncertainties in initial conditions and model physics, ensemble prediction systems generate multiple simulations by perturbing inputs, providing probabilistic guidance on frontal trajectories and intensity. ECMWF's Ensemble Prediction System (EPS) runs 51 members at 18 km resolution, quantifying spread in front locations to estimate confidence levels, such as the likelihood of a cold front stalling over a region.[93] NOAA's Global Ensemble Forecast System (GEFS), paired with GFS, uses 31 members to capture variability in frontal evolution, helping forecasters assess risks like rapid frontogenesis leading to heavy precipitation.[94] For short-term predictions, nowcasting techniques focus on 0-6 hour forecasts of front positions using blended observational data. Fusion of weather radar and satellite imagery allows real-time tracking of frontal boundaries, with radar detecting precipitation gradients along fronts and satellites providing cloud and moisture signatures for extrapolation.[95] Recent AI advancements, such as the FrontFinder algorithm, employ machine learning on reanalysis datasets to automatically detect and nowcast fronts with high precision, identifying boundaries like drylines and stationary fronts by analyzing gradients in temperature and wind fields.[30] In 2025, NOAA operationalized AI-enhanced versions of the GFS and GEFS under Project EAGLE, improving forecast speed and accuracy for frontal systems through machine learning emulations.[96] Verification of these forecasts uses skill scores tailored to spatial accuracy, particularly displacement errors that measure how far predicted front positions deviate from observations. Techniques like the Fractions Skill Score (FSS) evaluate front-related precipitation patterns, revealing typical 24-hour displacement errors below 100 km for major synoptic fronts in global models.[97] Complex wavelet methods further decompose errors into phase shifts, showing that ensemble averages reduce positional biases in frontal forecasts to under 150 km at 24 hours for mesoscale convective systems associated with fronts.[98] Advances in high-resolution convection-allowing models (CAMs) since the 2010s have enhanced frontal forecasting by explicitly resolving convective processes along boundaries. NOAA's High-Resolution Rapid Refresh (HRRR) model, operational since 2014 at 3 km grid spacing, improves predictions of frontally forced thunderstorms by assimilating radar data hourly, leading to better timing and intensity of precipitation bands.[99] These CAMs outperform coarser models in depicting sharp frontal contrasts, with studies demonstrating reduced errors in severe weather initiation near fronts due to finescale dynamics.[100]Climate Change Influences

Observed changes in the frequency and intensity of weather fronts vary by region and season, with a general poleward shift in storm tracks since the 1980s contributing to decreased front frequency in subtropical areas and increased activity in higher mid-latitudes.[101] In Europe, there has been a possible increase in the number of strong and extremely strong fronts during summer and autumn, potentially linked to enhanced atmospheric instability.[102] These shifts are assessed with medium confidence in IPCC AR6, reflecting high natural variability and data limitations in frontal detection.[101] Mechanisms driving these alterations include Arctic amplification, which reduces meridional temperature gradients and weakens baroclinicity, leading to slower-moving circulation patterns and fewer but more persistent frontal systems.[103] This amplification also promotes a wavier jet stream configuration with increased atmospheric blocking, enhancing the stagnation of weather fronts in mid-latitudes.[101] Such dynamic changes, combined with thermodynamic effects like greater atmospheric moisture capacity, amplify frontal precipitation potential.[101] Impacts on precipitation extremes have intensified, with atmospheric instability associated with fronts increasing by 8–32% over the Northern Hemisphere from 1979 to 2020, fostering more severe convective activity and heavy rainfall events.[104] In colder regions, warming has reduced the prevalence of snow-producing fronts while shifting precipitation toward rain, exacerbating flood risks in transitional seasons.[105] These changes contribute to broader alterations in extreme weather patterns, including more intense but less frequent frontal rain events.[101] Projections under the high-emissions RCP8.5 scenario indicate fewer mid-latitude fronts by 2100, but with greater intensity in associated rainfall due to enhanced moisture and storm vigor.[106] Regional variations include expanded stalled frontal systems in Europe and North America, heightening flood risks from prolonged heavy precipitation.[107] Overall, these trends suggest a transition to more extreme, persistent impacts from remaining fronts, with high confidence in increased precipitation intensity scaling at about 7% per 1°C of warming.[101]References

- https://earthobservatory.[nasa](/page/NASA).gov/features/Bjerknes/bjerknes_3.php