Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Welsh Not

View on Wikipedia

The Welsh Not was a token used by teachers at some schools in Wales, mainly in the 19th century, to discourage children from speaking Welsh at school, by marking out those who were heard speaking the language. It could be followed by an additional punishment; sometimes a physical punishment. There is evidence of the Welsh Not's use from the end of 18th to the start of the 20th century, but it was most common in the early- to mid- 19th century.

The token was seen as a teaching aid to help children learn English. Over time, however, excluding Welsh began to be viewed as an ineffective way of teaching English and by the end of the 19th century schools were encouraged to use some Welsh in lessons. There was a widespread desire for children to learn English among Welsh people in the 19th century and the Welsh Not was not part of any government policy.

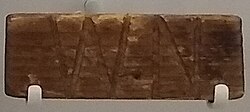

Accounts suggest that its form and the nature of its use could vary from place to place, but the most common form was a piece of wood suspended on a string that was put around the child's neck. Terms used historically include Welsh not, Welsh note, Welsh lump, Welsh stick, cwstom, Welsh Mark, and Welsh Ticket. The token remains prominent in Welsh collective memory.

Overview

[edit]

During the 19th century the primary function of day schools in Wales was the teaching of English.[2]: 437 The teaching of English in Welsh schools was generally supported by the Welsh public and parents who saw it as the language of economic advancement.[2]: 453, 457 Some schools practised what is now commonly called total immersion language teaching[2]: 438 and banned the use of Welsh in the school and playground to force children to use and become proficient in English. Some of these schools punished children caught speaking Welsh with the Welsh Not.[3]

The Welsh Not came in several forms and with different names (Welsh not,[4] Welsh note,[5] Welsh lump,[6] Welsh stick, Welsh lead, cwstom,[7] Welsh Mark,[8]: 24 Welsh Ticket[8]: 24 ) and was used in different ways. It was a token typically made of wood often inscribed with the letters 'WN' which might be worn around the neck.[7] Typically, following the start of some prescribed period of time, a lesson, the school day or the school week, it was given to the first child heard speaking Welsh[9] and would then be successively passed on to the next child heard speaking it. At the end of the period, the child with the token or all children who had held the token, might be punished. The nature of that punishment varies from one account to another; it might have been detention, the writing out of lines, or corporal punishment.[9][10][11][12]: 94 [13]

Martin Johnes, a historian who has studied the Welsh Not, comments that it was viewed as a "mode of instruction"; forcing children to practise English.[14] Similar approaches to teaching languages were used around Western Europe.[15] The method also encouraged children to participate in enforcing discipline by listening for peers speaking Welsh and was a way to keep solely Welsh-speaking children quiet; enforcing silence was considered important for managing a school.[16] The Welsh Not was not a government policy.[17] Some of the local committees and School Boards that administered non-private schools instructed teachers to refrain from using Welsh but most did not.[18] The Welsh Not was a practice introduced by individual teachers mostly on their own initiative.[19] Parents were generally supportive of physical punishment in schools[20] and appear to have been accepting of the Welsh Not.[21]

History

[edit]"Among other injurious effects, this custom has been found to lead children to visit stealthily the houses of their school-fellows for the purpose of detecting those who speak Welsh to their parents, and transferring to them the punishment due to themselves."

Johnes wrote that the practice may have originated in early modern grammar schools which aimed to teach Latin.[23] The first evidence of practices resembling the Welsh Not dates from around the 1790s; for instance, Rev Richard Warner wrote about schools in Flintshire "to give the children a perfect knowledge of the English tongue ... [the teachers force] the children to converse in it ... if ... one of them be detected in speaking a Welsh word, he is immediately degraded with the Welsh lump".[24] Accounts of the Welsh Not most frequently relate to the early- to mid-19th century.[25] Johnes believes it was probably widespread but not universal in the first half of the 19th century. There are records of it being used almost everywhere in Wales; but it was less common in Monmouthshire and Glamorgan where English was more established.[26] Accounts of children being beaten for speaking Welsh became less common after 1850; the penalty was increasingly likely to be non-physical where the Welsh Not was still used.[27]

Efforts by teachers to prohibit the speaking of Welsh in schools became gradually less common in the late 19th century.[28] The punishments used where prohibitions were in force were increasingly likely to be non-physical and less embarrassing for the children (e.g additional schoolwork).[29] However, some corporal punishment for speaking Welsh at school did continue.[30] Prohibitions on Welsh were most common in rural, heavily Welsh-speaking areas where teaching English was difficult.[31] Some use of the Welsh Not continued throughout the late-19th century.[32] In the late-19th century, the use and teaching of Welsh in schools began to receive moderate government support.[33] A few people, who grew up at the beginning of the 20th century, recalled in interviews that they saw or knew of the Welsh Not being used when they were children. However, there is no written evidence of the practice being used after 1900.[34]

Background

[edit]The use of corporal punishment was legal in all schools in the United Kingdom until it was mostly outlawed in 1986;[35] flogging or caning was in widespread use in British schools throughout the 1800s and early 1900s.[36]

Under Henry VIII the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542 simplified the administration and the law in Wales. English law and norms of administration were to be used, replacing the complex mixture of regional Welsh laws and administration.[12]: 66 Public officials had to be able to speak English[12]: 66 and English was to be used in the law courts. These two language provisions probably made little difference[12]: 68 since English had already replaced French as the language of administration and law in Wales in the late 14th century.[37] In practice this meant that courts had to employ translators between Welsh and English.[38]: 587 The courts were 'very popular' with the working class possibly because they knew the jury would understand Welsh and the translation was only for the benefit of the lawyers and judges.[38]: 589 The use of English in the law courts inevitably resulted in significant inconvenience to those who could not speak English.[12]: 69 It would also have led to the realisation that to get anywhere in a society dominated by England and the English, the ability to speak English would be a key skill.[12]: 69

Johnes writes that as the Act granted the Welsh equality with the English in law, that the result was "the language actually regained ground in Welsh towns and rural anglicised areas such as the lowlands of Gwent and Glamorgan" and that thus "Welsh remained the language of the land and the people".[12]: 69 Furthermore, Johnes writes that the religious turmoil at the time persuaded the state to support, rather than try to extinguish, the Welsh language.[12]: 69 In 1546, Brecon man John Prys had published the first Welsh-language book (Welsh: Yny lhyvyr hwnn, "In This Book"), a book containing prayers, which, as the Pope disapproved of it, endeared it to the Crown.[12]: 69 The result of the 1567 order by the Crown that a Welsh translation of the New Testament be used in every parish church in Wales (to ensure uniformity of worship in the kingdom) was that Welsh would remain the language of religion.[12]: 70 Davies says that as the (Tudor) government were to promote Welsh for worship, they had more sympathy for Welsh, than for Irish in Ireland, French in Calais, and than the government of Scotland had for Gaelic of the Highlands. The Tudors themselves were of partly Welsh origin.[39]: 235

[Question] "as far as your experience goes, there is a general desire for education, and the parents are desirous that their children should learn the English language?" [Reply] "Beyond anything."

In the first half of the 19th century, the only areas of Wales where English was widely spoken were places close to the Anglo-Welsh border, the Gower Peninsula and southern Pembrokeshire. However, the language was becoming more widespread in the industrialising areas due to migration.[41] Welsh speakers were keen for their children to learn English; knowing the language was felt to be a route to social mobility, made life more convenient and was a status symbol.[42] Contemporaries often said that parents wanted schools to be conducted in English. For instance, the Rev Bowen Jones of Narberth told an inquiry following the Rebecca Riots that a school conducted in Welsh in his area was unsuccessful; while, in schools where "the schoolmaster has to teach them English, and to talk English in the school, there is no room in the school-room to admit all that come".[43] The upper- and middle-classes in Wales, who generally spoke English, were also eager for the masses to learn the language. They believed it would contribute to Wales's economic development and that tenants or employees who could speak English would be easier to manage.[44]

The three-part Reports of the Commissioners of Inquiry into the State of Education in Wales, often referred to as the "Treason of the Blue Books" in Wales, was a publication written by the commissioners for British government in 1847 which investigated the Welsh educational system. The work caused uproar in Wales, where many perceived it as disparaging the Welsh, with the publication being particularly scathing in its view of nonconformity, the Welsh language, and Welsh morality.[7]: 2 The report was critical of schools that tried to exclude Welsh, seeing it as an ineffective way of teaching English,[45] and described the Welsh Not negatively.[46] The inquiry did not lead to any governmental action and the hostile reaction was mainly aimed at the comments about Welsh morality.[12]: 96

Reactions and impact

[edit]

Adults who experienced the Welsh Not as children recalled it with differing emotions, including anger,[47] indifference[48] and humour.[49] In the late 19th and early 20th centuries several accounts were published of this method of discipline, which described it as having been used at an unclear point in the relatively recent past.[50] Some writers in this period saw the Welsh Not as something imposed on Wales by England or the British government with the aim of destroying Welsh language; others disagreed, often seeing it as a result of Welsh people's desire to learn English.[51] The best-selling novel How Green Was My Valley (1939) by Richard Llewellyn includes an emotive description of the practice, which Johnes considers one of the most influential depictions of the punishment:[52]

"About her neck a piece of new cord, and from the cord, a board that hung to her shins and cut her as she walked. Chalked on the board … I must not speak Welsh in school … And the board dragged her down, for she was small, an infant, and the card rasped the flesh of her neck, and there were marks upon her shins where the edge of the board had cut. Loud she cried … and in her eyes the big tears of a child who is hurt, and has shame, and is frightened."

The punishment continues to be well known in Wales.[53] The Welsh Not has often been discussed in the media usually with an emphasis on its cruelty.[54] It has also featured in school teaching materials[55] and been linked to political debates.[56] It is sometimes incorrectly portrayed as a policy introduced by the British government.[57] According to the Encyclopaedia of Wales, "Welsh patriots view the Welsh Not(e) as an instrument of cultural genocide",[7] but "it was welcomed by some parents as a way of ensuring that their children made daily use of English".[7]

Government investigations in the mid-19th century indicated that excluding Welsh was not an effective way of teaching English,[58] some teachers made use of Welsh to help teach English in that period.[59] In the late 19th century, more Welsh began to be used informally in lessons to help facilitate the teaching of English. For instance, children might be given Welsh explanations of their English reading material or be given tasks translating between the two languages.[60] This frequently happened even at schools where children were punished for speaking Welsh.[61] A campaign developed for Welsh to be included in the curriculum.[62] Between 1889 and 1893, a series of changes were made to government policy: teachers in Welsh-speaking areas were now encouraged to teach English through Welsh, and schools could benefit financially from teaching Welsh as a subject.[63] The Welsh Department in the Board of Education encouraged the use of Welsh in lessons after its creation in 1907. Though teachers and parents in Welsh-speaking areas, whose priority was children learning English, often resisted this.[64]

In 2012, Chair of the Welsh Affairs Select Committee David T. C. Davies stated that the British government had not been responsible for suppressing the Welsh language in the 19th century, saying that the practice took place before government involvement in the education system began with the Education Act 1870, and that "the teachers who imposed the Welsh Not were Welsh and its imposition would have been done with the agreement of parents".[65]

The first academic study of the Welsh Not was completed by Martin Johnes in 2024.[66] He states that some government officials did want Welsh to cease to exist but the government never introduced policies to that end and believed that some use of Welsh was necessary in schools to effectively teach English.[67] He comments that the state had limited influence over the school system in the 19th century and it did not prohibit the use of Welsh in schools.[68] Johnes argued that there is little evidence to suggest that the Welsh Not caused the decline of Welsh. A large majority of children were not attending day school when it was most common and schools that attempted to completely exclude Welsh tended to be ineffective at teaching English.[69] He argued that;[70]

[The Welsh Not] was not a primary cause of linguistic change but the result of pedagogical misunderstandings and people’s desire for English. The first owed much to how underdeveloped education was, while the latter was rooted in Wales’s subordinate position within the United Kingdom. The Welsh Not was not imperialism in a direct sense, not least because the state never sanctioned it, but it was an example of how the Anglo-centricity of the United Kingdom produced cultural forces that had the similar effects to more overt imperialistic practices in the empire. The political, economic and cultural power of English was the direct cause of the decline of Welsh ... It was not beaten out of anyone.

Cultural interaction

[edit]In 2024, the 1923 Welsh Women's Peace message was translated into the Okinawan language from the perspective of the similarities between the Okinawan dialect cards and the Welsh Not.[71] The Asahi Shimbun claimed that the reconstruction of the Okinawan language is similar to the reconstruction of the Welsh language.[72] Japanese musicians also created a short film, inspired by the similarities between the history of Okinawan dialect tags and the Welsh Not.[73]

In literature

[edit]- Myrddin ap Dafydd (2019). Under the Welsh Not, Llanrwst, Gwasg Carreg Gwalch ISBN 978-1845276836

See also

[edit]- Dialect card Hōgenfuda (方言札; "dialect card"), used to promote standard speech in Japanese schools.

- Symbole, a similar object used in French schools as a means of punishment for students caught speaking regional dialects.

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Dimensions: length 58 mm (2.3 in); width 20 mm (0.79 in); depth 12 mm (0.47 in)[1]

- ^ The paragraph reads "The phrase – Welsh Note – might be unfamiliar to all the children of Wales. We have not seen nor heard so much as its name for many years. But forty and fifty years ago, the children of the day schools of Wales knew well what the Welsh Note was. It drew more reproaches and tears than can be described in words to many men who are still alive and well."

Citations

[edit]- ^ "Welsh not". National Museum Wales. Retrieved 26 April 2025.

- ^ "BBC Wales - History - Themes - Welsh language: The Welsh language in 19th century education". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- ^ Breverton, T. (2009). Wales A Historical Companion. United Kingdom: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 9781445609904.

- ^ Edwards, Thornton B. "The Welsh Not: A Comparative Analysis" (PDF). Carn (Winter 1995/1995). Ireland: Celtic League: 10.

- ^ Williams, Peter N. (2003). Presenting Wales from a to Y – The People, the Places, the Traditions: An Alphabetical Guide to a Nation's Heritage. Trafford. p. 275. ISBN 9781553954828.

- ^ a b c d e Davies, John; Baines, Menna; Jenkins, Nigel; Lynch, Peredur I., eds. (2008). The Welsh Academy Encyclopaedia of Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. p. 942. ISBN 9780708319536.

- ^ a b "Welsh and 19th century education". Wales History. BBC. Archived from the original on 28 April 2014. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- ^ "English Education in Wales". The Atlas. 22 January 1848. p. 6.

- ^ Ford Rojas, John Paul (14 November 2012). "Primary school children 'punished for not speaking Welsh'". The Telegraph. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Johnes, Martin (2019). Wales: England's Colony?: The Conquest, Assimilation and Re-creation of Wales. Parthian. ISBN 978-1912681419.

- ^ Maelor, Lord (15 June 1967). "Welsh Language Bill Hl". Hansard. 283. Retrieved 14 September 2021.

- ^ Johnes 2024, p. 62.

- ^ Johnes 2024, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Johnes 2024, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Johnes 2024, p. 197.

- ^ Johnes 2024, pp. 301–302.

- ^ Johnes 2024, p. 3.

- ^ Johnes 2024, p. 288.

- ^ Johnes 2024, pp. 297–298.

- ^ Reports of the Commissioners of Inquiry into the State of Education in Wales. London: William Clowes and Sons. 1847.

- ^ Johnes 2024, p. 60.

- ^ Johnes 2024, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Johnes 2024, p. 47.

- ^ Johnes 2024, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Johnes 2024, p. 66.

- ^ Johnes 2024, p. 125.

- ^ Johnes 2024, p. 134.

- ^ Johnes 2024, p. 137.

- ^ Johnes 2024, p. 127.

- ^ Johnes 2024, pp. 117–118.

- ^ Johnes 2024, pp. 181–182.

- ^ Johnes 2024, pp. 185–186.

- ^ "Country report for UK". Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children. June 2015.

- ^ Gibson, Ian (1978). The English vice: Beating, sex, and shame in Victorian England and after. London: Duckworth. ISBN 0-7156-1264-6.

- ^ O'Neill, Pamela (2013). "The Status of the Welsh Language in Medieval Wales". The Land Beneath the Sea. University of Sydney Celtic Studies Foundation. pp. 59–74.

- ^ Davies, John (1994). A History of Wales. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-014581-8.

- ^ Report of the Commissioners of Inquiry for South Wales. London: William Clowes and Sons. 1844. p. 102.

- ^ Johnes 2024, p. 37.

- ^ Johnes 2024, pp. 280, 293–296.

- ^ Johnes 2024, p. 296.

- ^ Johnes 2024, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Johnes 2024, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Johnes 2024, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Johnes 2024, pp. 241–246.

- ^ Johnes 2024, pp. 246–247.

- ^ Johnes 2024, pp. 248–249.

- ^ Johnes 2024, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Johnes 2024, pp. 7–9, 21.

- ^ Johnes 2024, pp. 10–12.

- ^ Johnes 2024, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Johnes 2024, pp. 11, 14–16.

- ^ Johnes 2024, pp. 16–18.

- ^ Johnes 2024, pp. 9, 14, 18–19.

- ^ Johnes 2024, pp. 11, 13–16.

- ^ Johnes 2024, pp. 81–82, 201, 205–207 210–211.

- ^ Johnes 2024, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Johnes 2024, pp. 160–162.

- ^ Johnes 2024, p. 163.

- ^ Johnes 2024, pp. 179–180.

- ^ Johnes 2024, p. 181.

- ^ Johnes 2024, p. 185.

- ^ Shipton, Martin (17 November 2012). "Welsh Not 'a myth to stir up prejudice against the British Government'". WalesOnline. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- ^ Johnes 2024, pp. 22, 27–28.

- ^ Johnes 2024, p. 13.

- ^ Johnes 2024, pp. 197–198.

- ^ Johnes 2024, pp. 239–240.

- ^ Johnes 2024, p. 360.

- ^ "Global Peace and Goodwill Message translated into Uchinaaguchi for first time". www.okinawatimes.co.jp. 17 May 2024. Retrieved 26 April 2025.

- ^ "Japanese language subjected to 'Welsh Not'-style punishment takes inspiration from Cymraeg". nation.cymru. 16 May 2022. Retrieved 26 April 2025.

- ^ "Japanese singer to shoot video inspired by the Welsh Not in Cardiff". nation.cymru. 28 July 2024. Retrieved 26 April 2025.

- Johnes, Martin (2024). Welsh Not: Elementary Education and the Anglicisation of Nineteenth-Century Wales (PDF). University of Wales Press. ISBN 9781837721818.

External links

[edit]- Photographs of Welsh Not artefacts at the National Museum of Wales

- Owen Morgan Edwards describes his experience of the Welsh Not in school in Llanuwchllyn in his book Clych Atgof.