Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

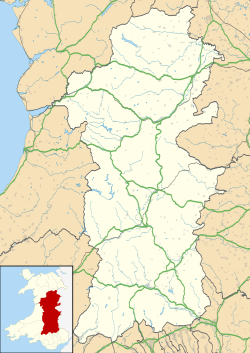

Brecon

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

Brecon (/ˈbrɛkən/;[3] Welsh: Aberhonddu; pronounced [ˌabɛrˈhɔnði]), archaically known as Brecknock, is a market town in Powys, mid Wales. In 1841, it had a population of 5,701.[4] The population in 2001 was 7,901,[5] increasing to 8,250 at the 2011 census. Historically it was the county town of Brecknockshire (Breconshire); although its role as such was eclipsed with the formation of the County of Powys, it remains an important local centre. Brecon is the third-largest town in Powys, after Newtown and Ystradgynlais. It lies north of the Brecon Beacons mountain range, but is just within the Brecon Beacons National Park.

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]The Welsh name, Aberhonddu, means "mouth of the Honddu". It is derived from the River Honddu, which meets the River Usk near the town centre, a short distance away from the River Tarell which enters the Usk a few hundred metres upstream. After the Dark Ages the original Welsh name of the kingdom in whose territory Brecon stands was (in modern orthography) "Brycheiniog", which was later anglicised to Brecknock or Brecon, and probably derives from Brychan, the eponymous founder of the kingdom.[6]

Before the building of the bridge over the Usk, Brecon was one of the few places where the river could be forded. In Roman Britain Y Gaer (Cicucium) was established as a Roman cavalry base for the conquest of Roman Wales and Brecon was first established as a military base.[7]

Norman control

[edit]The confluence of the River Honddu and the River Usk made for a valuable defensive position for the Norman castle which overlooks the town, built by Bernard de Neufmarche in the late 11th century.[8]: 80 Gerald of Wales came and made some speeches in 1188 to recruit men to go to the Crusades.[9]

Town walls

[edit]Brecon's town walls were constructed by Humphrey de Bohun after 1240.[10]: 8 The walls were built of cobble, with four gatehouses and was protected by ten semi-circular bastions.[10]: 9 In 1400 the Welsh prince Owain Glyndŵr rose in rebellion against English rule, and in response in 1404, 100 marks was spent by the royal government improving the fortifications to protect Brecon in the event of a Welsh attack. Brecon's walls were largely destroyed during the English Civil War. Today only fragments survive, including some earthworks and parts of one of the gatehouses; these are protected as scheduled monuments.[11]

In Shakespeare's play King Richard III, the Duke of Buckingham is suspected of supporting the Welsh pretender Richmond (the future Henry VII), and declares:

O, let me think on Hastings and be gone

To Brecknock, while my fearful head is on![12]

Priory and cathedral

[edit]

A priory was dissolved in 1538, and Brecon's Dominican Friary of St Nicholas was suppressed in August of the same year.[13] About 250 m (270 yd) north of the castle stands Brecon Cathedral, a fairly modest building compared to many cathedrals. The role of cathedral is a fairly recent one, and was bestowed upon the church in 1923 with the formation of the Diocese of Swansea and Brecon from what was previously the archdeaconry of Brecon — a part of the Diocese of St Davids.[14]

St Mary's Church

[edit]Saint Mary's Church began as a chapel of ease to the priory but most of the building is dated to later medieval times. The West Tower, some 27 m (90 ft) high, was built in 1510 by Edward, Duke of Buckingham at a cost of £2,000. The tower has eight bells which have been rung since 1750, the heaviest of which weighs 810 kg (16 long hundredweight). They were cast by Rudhall of Gloucester. In March 2007 the bells were removed from the church tower for refurbishment. When the priory was elevated to the status of a cathedral, St Mary's became the parish church.[15][16] It is a Grade II* listed building.[17]

St David's Church, Llanfaes

[edit]

The Church of St David, referred to locally as Llanfaes Church, was probably founded in the early sixteenth century. The first parish priest, Maurice Thomas, was installed there by John Blaxton, Archdeacon of Brecon in 1555. The name is derived from the Welsh – Llandewi yn y Maes – which translates as 'St David's in the field'.[18]

Plough Lane Chapel, Lion Street

[edit]Plough Lane Chapel, also known as Plough United Reformed Church, is a Grade II* listed building. The present building dates back to 1841 and was re-modelled by Owen Morris Roberts.[19]

St Michael's Church

[edit]After the Reformation, some Breconshire families such as the Havards, the Gunters and the Powells persisted with Catholicism despite its suppression. In the 18th Century a Catholic Mass house in Watergate was active, and Rev John Williams was the local Catholic priest from 1788 to 1815. The present parish priest is Rev Father Jimmy Sebastian Pulickakunnel MCBS since 2012. The Watergate house was sold in 1805, becoming the current Watergate Baptist Chapel, and property purchased as the priest's residence and a chapel between Wheat Street and the current St Michael Street, including the "Three Cocks Inn"; about this time Catholic parish records began again. The normal round of bishop's visitations and confirmations resumed in the 1830s. In 1832 most civil liberties were restored to Catholics and they became able to practise their faith more openly. A simple Gothic church, dedicated to St Michael and designed by Charles Hansom, was built in 1851 at a cost of £1,000.[13]

Military town

[edit]The east end of town has two military establishments:

- Dering Lines, home to the Infantry Battle School (formerly Infantry Training Centre Wales)[20]

- The Barracks, Brecon, home to 160th (Wales) Brigade.[21]

Approximately 9 miles (14 km) to the west of Brecon is Sennybridge Training Area, an important training facility for the British Army.[22]

Geography

[edit]The town sits within the Usk valley at the point where the Honddu and Tarell rivers join it from north and south respectively. Two low hills overlook the town, the 331m high Pen-y-crug to its northwest and 231m high Slwch Tump to the east. Both are crowned by Iron Age hillforts. The modern administrative community includes the town of Brecon on the north bank of the Usk together with the smaller settlement of Llanfaes on its southern bank. Llanfaes is built largely on the floodplain of the Usk and the Tarell; embankments and walls protect parts of both Brecon and Llanfaes from this risk.[23]

Governance

[edit]

There are two tiers of local government covering Brecon, at community (town) and county level: Brecon Town Council and Powys County Council. The town council is based at Brecon Guildhall on the High Street.[24]

The town council elects a mayor annually. In May 2018 it elected its first mixed race mayor, local hotelier Emmanuel (Manny) Trailor.[25]

Controversy

[edit]In 2010 the Town Council installed a plaque to the slave-trader Captain Thomas Phillips captain of the Hannibal slave ship.[26] During the worldwide Black Lives Matter protests the plaque was removed and thrown into the River Usk.[citation needed][27] Following the protests the Council passed two resolutions on 20 September 2020 to display the plaque in the local museum, Y Gaer, and to request that it is displayed as part of a suitable exhibit detailing the wider context, without being restored. It was also resolved unanimously that a working group is established to consider whether a new plaque, new work of art, or loaned artwork should be commissioned, and where any new piece should be located. [28]

Administrative history

[edit]Brecon was an ancient borough. Its date of becoming a borough is unknown, but it was described as having burgesses in 1100 and its first known charter was issued in 1276.[29] Until 1536, the town formed part of the wider Lordship of Brecknock, a marcher lordship. In 1536 the new county of Brecknockshire was created, with Brecon as its county town.[30]

The borough of Brecon's responsibilities were originally primarily judicial, holding various courts. The borough council also owned the manorial rights to the borough, oversaw the town's market and fairs, and ran elections for the borough's member of parliament. In 1776 a separate body of improvement commissioners was established to supply the town with water and pave and light the streets.[31]

The borough was reformed to become a municipal borough in 1836 under the Municipal Corporations Act 1835, which standarised how most boroughs operated across the country.[32] The improvement commissioners were abolished in 1850 when their functions were taken over by the borough council.[33][34]

The borough was abolished in 1974, with its area instead becoming a community called Brecon within the larger Borough of Brecknock in the new county of Powys. The former borough council's functions therefore passed to Brecknock Borough Council, which was in turn abolished in 1996 and its functions passed to Powys County Council.[35][36]

Education

[edit]

Brecon has primary schools, with a secondary school and further education college (Brecon Beacons College) on the northern edge of the town. The secondary school, known as Brecon High School, was formed from separate boys' and girls' grammar schools ('county schools') and Brecon Secondary Modern School, after comprehensive education was introduced into Breconshire in the early 1970s. The town is home to an independent school, Christ College, which was founded in 1541.[37]

Transport

[edit]

The junction of the east–west A40 (London-Monmouth-Carmarthen-Fishguard) and the north–south A470 (Cardiff-Merthyr Tydfil-Llandudno) is on the east side of Brecon town centre. The nearest airport is Cardiff Airport.[38]

The town's primary public transport hub is the Brecon Interchange at the B4601 Heol Gouesnou, served mainly by the long-distance T4, T6 and T14 routes operated by TrawsCymru. Local services 40A and 40B, operated by Stagecoach South Wales, connect the town centre with the suburbs, operating at a roughly-hourly frequency.[39]

Monmouthshire and Brecon Canal

[edit]The Monmouthshire and Brecon Canal runs for 35 miles (56 km) between Brecon and Pontnewydd, Cwmbran. It then continues to Newport, the towpath being the line of communication and the canal being disjointed by obstructions and road crossings. The canal was built between 1797 and 1812 to link Brecon with Newport and the Severn Estuary. The canalside in Brecon was redeveloped in the 1990s and is now the site of two mooring basins and Theatr Brycheiniog.[40]

Usk bridge

[edit]

The bridge carries the B4601 across the River Usk. A plaque on a house wall adjacent to the eastern end of the bridge records that the present bridge was built in 1563 to replace a medieval bridge destroyed by floods in 1535. It was repaired in 1772 and widened in 1794 by Thomas Edwards, the son of William Edwards of Eglwysilan. It had stone parapets until the 1970s when the present deck was superimposed on the old structure. The bridge was painted by J. M. W. Turner c.1769.[41]

Former railways

[edit]The Neath and Brecon Railway reached Brecon in 1867, terminating at Free Street. By this point, Brecon already had two other railway stations:

- Watton – from 1 May 1863 when the Brecon and Merthyr Railway to Merthyr Tydfil was opened for traffic[42]

- Mount Street – in September 1864, with Llanidloes by the Mid Wales Railway which linked to the Midland Railway at Talyllyn Junction. The three companies consolidated their stations at a newly rebuilt Free Street Joint Station from 1871[43] and the station finally closed in 1872[44]

Hereford, Hay and Brecon Railway

[edit]

The Hereford, Hay and Brecon Railway was opened gradually from Hereford towards Brecon. The first section opened in 1862, with passenger services on the complete line starting on 21 September 1864.[45] The Midland Railway Company (MR) took over the HH&BR from 1 October 1869, leasing the line by an Act of 30 July 1874 and absorbing the HH&BR in 1876.[46] The MR was absorbed into the London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS) on 1 January 1923.[47]

Passenger services to Merthyr ended in 1958, Neath in October 1962 and Newport in December 1962. In 1962 the important line to Hereford closed. Therefore, Brecon lost all its train services before the 1963 Reshaping of British Railways report (often referred to as the Beeching Axe) was implemented.[48]

Culture

[edit]Brecon hosted the National Eisteddfod in 1889.[49]

August sees the annual Brecon Jazz Festival. Concerts are held in both open air and indoor venues, including the town's market hall and the 400-seat Theatr Brycheiniog, which opened in 1997.[40]

October sees the annual 4-day weekend Brecon Baroque Music Festival, organised by leading violinist Rachel Podger.[50]

Idris Davies put "the pink bells of Brecon" in his poem published as XV in Gwalia Deserta (by T. S. Eliot). This was copied in "Quite Early One Morning" by Dylan Thomas, put to music by Pete Seeger as the song "The Bells of Rhymney", then recorded by the Byrds where it became known to millions although by then the Brecon line had gone missing.[51]

Points of interest

[edit]

- Brecon Castle

- Brecon Beacons National Park Visitor Centre (also known as the Mountain Centre)

- Brecon Beacons Food Festival

- Brecon Cathedral, the seat of the Diocese of Swansea and Brecon

- Brecon Jazz Festival

- Christ College, Brecon

- Regimental Museum of The Royal Welsh

- Theatr Brycheiniog (Brecon Theatre)

- Y Gaer

Notable people

[edit]

- Sibyl de Neufmarché (ca.1100 – after 1143), Countess of Hereford, suo jure Lady of Brecknock

- Gerald of Wales (ca.1146 – ca.1223), a Cambro-Norman priest and historian.

- William de Braose (ca.1197 – 1230), a Marcher lord.[52]

- Dafydd Gam (ca.1380 – 1415), archer, died fighting for Henry V at the Battle of Agincourt

- Edward Stafford, 3rd Duke of Buckingham (1478–1521) an English nobleman.

- Dafydd Epynt (15th Century), poet

- Hugh Price (ca.1495 – 1574), founder of Jesus College, Oxford

- Admiral Sir William Wynter (ca.1521 – 1589), principal officer of the Council of the Marine

- Henry Vaughan (1621–1695), physician and author, a major Metaphysical poet.[53]

- John Jeffreys (ca.1623 - 1689), landowner and politician, first master of the Royal Hospital Kilmainham

- Captain Thomas Phillips[54] (late 17th century), commander of the Hannibal slave ship

- Howell Harris (1714–1773), Calvinistic Methodist evangelist

- Diederich Wessel Linden (fl. 1745–1768; d. 1769), specialist on mining and the medicinal uses of mineral waters

- Thomas Coke (1747–1814), Mayor of Brecon in 1772 and the first Methodist bishop.[55]

- Sarah Siddons (1755–1831), tragedienne actress.[56]

- David Price (1762–1835), orientalist and officer in the East India Company.

- Charles Kemble (1775–1854), actor, younger brother of Sarah Siddons.[57]

- John Evan Thomas (1810–1873), a Welsh sculptor

- Mordecai Jones (1813-1880), businessman, pioneered the South Wales coalfield, Mayor of Brecon in 1854.

- Frances Hoggan (1843–1927), first British woman to receive a doctorate in medicine

- Ernest Howard Griffiths (1851–1932), physicist and academic

- Gwenllian Morgan (1852–1939), the first woman in Wales to hold the office of Mayor.

- Llewela Davies (1871–1952), pianist and composer

- Dame Olive Wheeler (1886–1963), educationist, psychologist and university lecturer

- Captain Richard Mayberry (1895–1917), World War I flying ace

- Lt Col S. F. Newcombe (1878–1956), Army Officer and associate of T. E. Lawrence.

- Tudor Watkins, Baron Watkins (1903–1983), politician and MP

- John Fullard (1907–1973), tenor singer with the Covent Garden Opera

- Jet Naessens (1915–2010), Belgian actress and director; born in Brecon where her parents had fled during World War I

- George Melly (1926–2007), trad jazz singer, art critic and writer, retreat at Brecon between 1971 and 1999

- Gareth Gwenlan (1937–2016), TV producer, director and executive

- Roger Glover (born 1945), bassist and songwriter with the band Deep Purple

- Jeb Loy Nichols (born ca.1965), musician

- Nia Roberts (born 1972), actress

- Gerard Cousins (born 1974), guitarist, composer and arranger.

- Natasha Marsh (born 1975), soprano singer.

- Sian Reese-Williams (born 1981), actress

Sport

[edit]- Frederick Bowley (1873–1943), a first-class cricketer for Worcestershire

- Walley Barnes (1920–1975), footballer with 299 club caps and 22 for Wales and a broadcaster.

- Andy Powell (born 1981), Welsh Rugby Union international number eight

- Sam Hobbs (born 1988), rugby union player with Cardiff Blues

- Jessica Allen (born 1989), a Welsh racing cyclist.

- Emma Plewa (born 1990), footballer with 20 caps with Wales women

Town twinning

[edit]Brecon is twinned with:

- Saline, Michigan, United States

- Blaubeuren, Baden-Württemberg, Germany. (Blaubeuren is twinned with Brecknockshire, which is an area of Powys, rather than with the town of Brecon.)

- Gouesnou, Brittany, France

- Dhampus, Kaski District, Nepal

References

[edit]- ^ "Town population 2011". Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ^ "Brecon Town Council". Brecon Town Council. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ "Brecon". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 15 January 2024.

- ^ The National Cyclopaedia of Useful Knowledge, Vol III, (1847) London, Charles Knight, p.765.

- ^ "Parish Headcounts: Powys", Census, Office for National Statistics, 2001, archived from the original on 13 June 2011, retrieved 22 November 2009.

- ^ "Brychan Brycheiniog, King of Brycheiniog". Early English Kingdoms. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ "A short guide to Brecon Gaer Roman Fort". Clwyd Powys Archaeological Trust. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ^ Davies (2008).

- ^ "Gerald's Journey through Wales in 1188". History Points. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ a b Pettifer (2000).

- ^ Davis, Philip, "Brecon Town Walls", Gatehouse, retrieved 13 October 2011.

- ^ Cornwall, Barry (1853). The Plays of Shakspere, Carefully Revised from the Best Authorities. Vol. 2. p. 1250.

- ^ a b "History of St. Michael's Church – St. Michael's Catholic Church, Brecon". stmichaelsrcbrecon.org.uk. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ "Swansea and Brecon". Crockford's Clerical Directory. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ "Bellringing". St Mary's Church in Wales. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ "History". St Mary's Church Brecon. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ Cadw. "Church of St Mary, Brecon, Powys (Grade II*) (7015)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ Poole, Edwin (1886). The Illustrated History and Biography of Brecknockshire: From the Earliest Times to the Present Day. Illustrated by Several Engravings and Portraits (Public domain ed.). Edwin Poole. p. 67.

- ^ Cadw. "Plough Lane Chapel, Brecon (6945)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ "Brecon", Brigade of Gurkhas, UK: Army, archived from the original on 18 November 2004.

- ^ "Summary of Future Reserves 2020 (FR20) implementation measures within Wales" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 April 2014. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ "160the Wales Brigade", 5th Division, UK: Army[permanent dead link].

- ^ Barclay, W.J.; Davies, J.R.; Humpage, A.J.; Waters, R.A.; Wilby, P.R.; Williams, M.; Wilson, D. (2005). Geology of the Brecon District. Keyworth, Nottingham: British Geological Survey. p. 31. ISBN 0-85272-511-6.

- ^ "Brecon Town Council". Retrieved 15 November 2024.

- ^ "First mixed-race mayor elected by Brecon Town Council". The Brecon & Radnor Express. 16 May 2018. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- ^ "Controversial plaque commemorating Brecon's links to slave trader is removed ahead of review". The Brecon & Radnor Express. 11 June 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2025.

- ^ Thomas, James (12 June 2020). "Slave trader's town centre plaque stripped from wall in Brecon". Hereford Times. p. 1.

- ^ "Minutes of a Meeting of the Brecon Town Council held remotely via GoToMeeting on Monday 28 September 2020 at 7.00 P.M." (PDF). brecontowncouncil.org.uk.

- ^ "Brecon Boroughs". The History of Parliament. Retrieved 15 November 2024.

- ^ Laws in Wales Act 1535. 1536. p. 246. Retrieved 14 November 2024.

- ^ Report of the Commissioners appointed to inquire into the Municipal Corporations in England and Wales: Appendix 1. 1835. pp. 177–184. Retrieved 15 November 2024.

- ^ Municpal Corporations Act. 1835. p. 459. Retrieved 15 November 2024.

- ^ Lawes, Edward (1851). The Act for Promoting the Public Health, with notes. London: Shaw and Sons. pp. 260–261. Retrieved 15 November 2024.

- ^ "Brecon Urban District / Municipal Borough". A Vision of Britain through Time. GB Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth. Retrieved 15 November 2024.

- ^ Local Government Act 1972

- ^ Local Government (Wales) Act 1994

- ^ "Christ College Brecon in £5m anniversary investment boost". BBC News. BBC. 5 July 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- ^ "Getting There". Brecon Beacons. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ "40A, 40B - Brecon - Brecon".

- ^ a b "Theatr Brycheiniog - The Theatres Trust". theatrestrust.org.uk. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- ^ "Joseph Mallord William TurnerBrecon Bridge c.1798-9". Tate. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ^ Barrie, D.S.M. (1980) [1957]. The Brecon and Merthyr Railway. Trowbridge: The Oakwood Press. ISBN 0-85361-087-8.

- ^ "Railway stations", Victorian Brecon, UK: Powys

- ^ Railway Passenger Stations by M.Quick page 96

- ^ Butt 1995, p. 103

- ^ Awdry 1990, p. 80

- ^ Railways Act 1921, HMSO, 19 August 1921

- ^ Garry Keenor. "The Reshaping of British Railways – Part 1: Report". The Railways Archive. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- ^ "Past locations". National Eisteddfod. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- ^ "Brecon Baroque Music Festival". Music at Oxford. 21 October 2020. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ "The Bells of Rhymney". Welsh Not. 2 May 2013. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 432.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 955.

- ^ Caldicott, Rosemary L (1 March 2024). Voyage of Despair. The Hannibal, its captain and all who sailed in her, 1693-1695 (1st ed.). Bristol: Bristol Radical History Group. p. 250. ISBN 978-1-911522-63-8. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 655.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 37–38.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 723–724, see page 724.

Charles Kemble (1775–1854), a younger brother of....

Bibliography

[edit]- Awdry, Christopher (1990). Encyclopaedia of British Railway Companies. Sparkford: Patrick Stephens Ltd. ISBN 1-8526-0049-7. OCLC 19514063. CN 8983.

- Butt, R. V. J. (October 1995). The Directory of Railway Stations: details every public and private passenger station, halt, platform and stopping place, past and present (1st ed.). Sparkford: Patrick Stephens Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85260-508-7. OCLC 60251199. OL 11956311M.

- Caldicott, R. L. (2024). Voyage of Despair. The Hannibal, its captain and all who sailed in her, 1693-1695. BRHG Books. ISBN 978-1-911522-63-8

- Davies, John; Jenkins, Nigel (2008). The Welsh Academy Encyclopaedia of Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-0-7083-1953-6.

- Pettifer, Adrian (2000). Welsh Castles: a Guide by Counties. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-778-8.

External links

[edit] Brecon travel guide from Wikivoyage

Brecon travel guide from Wikivoyage- Brecon Town Council website

Brecon

View on GrokipediaBrecon (Welsh: Aberhonddu) is a historic market town and community in Powys, mid Wales, situated at the confluence of the Rivers Usk and Honddu.[1] With a population of approximately 8,000, it functions as the administrative centre for Powys and lies on the northern fringe of the Bannau Brycheiniog (formerly Brecon Beacons) National Park.[2][3]

The town boasts a rich historical legacy, with evidence of human occupation spanning from the Neolithic era through Roman, medieval, and industrial periods, evidenced by archaeological sites and conserved architecture.[4] Notable landmarks include Brecon Cathedral, Georgian buildings, and the Monmouthshire and Brecon Canal, which contribute to its appeal as a tourism hub for walking, cycling, and cultural events.[3][5] As a longstanding market town, Brecon has served as a key commercial and strategic location in southern Wales since medieval times, bolstered by its position on historic trade routes.[6]

History

Pre-Norman Origins

![Brecon River Usk][float-right] The area surrounding modern Brecon, known historically as part of Brycheiniog, exhibits limited archaeological evidence of prehistoric settlement directly within the town site, with primary indications of human activity concentrated in nearby hillforts during the Iron Age (c. 800 BC–AD 75). Slwch Camp, a univallate hillfort located on a prominent hill approximately 1 km north of Brecon, overlooks the River Usk valley and represents a key defensive structure associated with Celtic tribes, providing strategic oversight of routes and resources in the region.[1] Similarly, Pen-y-Crug hillfort to the east served comparable functions, reflecting dispersed settlement patterns rather than centralized occupation. Excavations at these sites reveal ramparts and enclosures typical of Iron Age defenses, though no extensive domestic remains have been uncovered to suggest large-scale communities.[7] Sparse finds, including possible prehistoric artifacts on the bluff at the confluence of the Usk and Honddu rivers—later the site of Brecon Castle—hint at transient or small-scale activity, but lack corroboration for permanent habitation.[8] During the Roman period, the establishment of Y Gaer (Brecon Gaer) fort around AD 75 marked a significant military presence approximately 3 km west of modern Brecon, encompassing about 4 hectares and housing an auxiliary ala of cavalry, underscoring the site's role in securing the Usk valley against native resistance. Archaeological investigations at the fort have yielded no evidence of pre-Roman Iron Age settlement on the site itself, with pottery and structural remains indicating de novo construction amid the existing landscape of local hillforts.[9] The fort's location facilitated control over riverine crossings and nascent road networks linking to broader Roman infrastructure, such as routes toward modern Swansea and Carmarthen, though direct evidence of a civilian vicus or bridge at Brecon remains absent.[10] Roman occupation persisted intermittently until the 4th century, with associated finds like samian ware and military equipment attesting to integration with indigenous populations, yet without fostering urban development in the core Brecon area.[11] Post-Roman and early medieval phases prior to the Norman Conquest show continuity in rural land use but no emergence of substantial settlement at Brecon, consistent with excavation records emphasizing agricultural and dispersed habitation over nucleated growth. The strategic value of the Usk crossing, formed by the river's meandering hydrology and gravelly bed conducive to fording, likely influenced prehistoric and Roman site selection, as evidenced by the alignment of forts and roads with the valley floor.[12] By the 10th–11th centuries, the region fell within the Kingdom of Brycheiniog, with potential ecclesiastical sites like a pre-Norman church precursor to later structures, but archaeological data confirm the absence of major urban foundations until Norman interventions.[12] Overall, empirical findings portray Brecon's pre-Norman origins as peripheral to primary settlement hubs, defined by defensive outposts and transient exploitation rather than enduring communities.Norman Conquest and Medieval Development

The Norman conquest of Brycheiniog culminated in the establishment of Brecon as a strategic stronghold following Bernard de Neufmarché's victory over Welsh forces, with the construction of a motte-and-bailey castle commencing around 1093 to secure control over the River Usk crossing and surrounding fertile valleys essential for feudal agriculture and supply lines.[13][14] This fortification addressed the persistent threat of Welsh resistance, enabling Norman lords to impose authority through military deterrence and resource extraction from subjugated lands.[7] Concurrent with military consolidation, Bernard de Neufmarché founded the Benedictine Priory of St John the Evangelist in 1093 on the site of an earlier Celtic church, transforming it into a center for ecclesiastical administration that reinforced Norman governance by integrating religious authority with secular power and attracting monastic settlers to bolster the nascent settlement.[15][16] St Mary's Church emerged in the 12th century as a chapel of ease affiliated with the priory, serving the growing borough population and facilitating local worship amid expanding trade activities.[17][18] By the 13th century, Brecon had evolved into a fortified market town, encircled by defensive walls constructed after 1240 to protect against renewed Welsh incursions while enclosing a borough layout conducive to commerce.[12] A royal charter granted in 1227, modeled on Hereford's, conferred borough status, market rights, and assize functions, fostering economic vitality through regulated trade fairs and judicial proceedings that drew merchants and integrated Brecon into broader Anglo-Norman networks.[19] These developments underscored the causal interplay of defensive necessities and feudal incentives, prioritizing settlement stability to sustain lordly revenues from tolls, rents, and agrarian surpluses.[20]

Early Modern Period

The Priory of St John at Brecon was dissolved in 1538 as part of Henry VIII's suppression of religious houses across England and Wales, with its church repurposed as the town's parish church while monastic buildings were repurposed or granted to secular owners, including initially the Bishop of St Davids and later Sir John Price, a local commissioner involved in the dissolutions who received monastic estates in Breconshire as reward.[21][22] This transition reflected broader Reformation pressures in Wales, where the Act of Union in 1536 integrated Breconshire into English administrative and religious frameworks, though residual Catholic sympathies persisted, evidenced by Jesuit activity and symbols on local tombs into the late 16th century.[23][24] During the English Civil War in the 1640s, Brecon's medieval defenses suffered significant damage, with the town walls largely demolished by Parliamentary forces and parts of Brecon Castle partially destroyed amid Royalist-Parliamentarian conflicts in the region.[12] Brecon itself saw limited direct engagements but aligned administratively with Parliamentarian control in Breconshire, contributing to the slighting of fortifications to prevent their reuse.[25] Brecon maintained its role as the county town of Breconshire into the 17th century, hosting quarter sessions for judicial and administrative functions, with records documenting meetings in the town from at least 1674 onward, handling matters like poor relief and local governance under justices of the peace.[26][27] Markets and fairs continued under earlier charters, including a royal grant in 1556, supporting trade in agricultural produce amid a rural economy dominated by pastoral farming, with wool and cattle driving local exchange rather than manufacturing or extensive river navigation on the Usk, which primarily powered mills on tributaries like the Honddu.[1][28] Industrial development remained minimal, preserving Brecon's focus on agrarian markets and limited overland commerce.[12]Industrial and Victorian Era

The completion of the Brecknock and Abergavenny Canal to Brecon in 1800 enabled efficient transport of lime, coal, and agricultural produce, stimulating trade with industrializing regions downstream.[29] The canal's full extension from Newport reached Brecon by 1812, though financial challenges delayed parts of the project.[30] This infrastructure supported Brecon's role as a market hub without fostering heavy local manufacturing. Military infrastructure expanded with additions to the Watton Barracks between 1842 and 1844, building on the original 1805 armaments store to house regiments amid Britain's imperial commitments.[31] These developments reflected Brecon's growing administrative and garrison functions as the county town. As an assize town, Brecon hosted superior courts in the newly built Shire Hall from the early 1840s, underscoring its judicial prominence in Brecknockshire.[32] The structure accommodated twice-yearly sessions, reinforcing the town's centrality in regional governance and markets. Railway arrival accelerated connectivity, with the Hereford, Hay and Brecon Railway opening sections from 1862 to 1864, linking Brecon to Hereford and facilitating goods movement toward coal valleys.[33] The Mid-Wales Railway extended service to Llanidloes in September 1864, though undercapitalization limited operational efficiency.[34] Census data indicate modest population growth, from 5,609 residents in 1841 to 5,975 in 1851, before stabilizing at 5,634 by 1861, driven by transport improvements rather than industrial employment booms.[35] Brecon's economy remained agrarian and service-oriented, with infrastructure enhancements providing indirect benefits from distant coalfields.[34]20th Century and World Wars

During the First World War, Brecon Barracks served as a primary training site for the Brecknockshire Battalion of the South Wales Borderers, where recruits underwent intensive musketry and infantry drills following the unit's mobilisation in 1914.[36] The barracks, expanded that year through War Office acquisition of adjacent land, facilitated the assembly and preparation of local volunteers who were later garrisoned in Aden, contributing to imperial defence efforts amid the battalion's overall deployment of over 1,000 men.[37] Local enlistments from Brecon swelled the ranks, with the town experiencing economic strain from labour shortages but bolstered by military-related supply demands on agriculture and small industries. In the Second World War, Brecon's military infrastructure supported home defence through the 1st (Brecon) Battalion of the Brecknockshire Home Guard, formed in May 1940 from Local Defence Volunteers in reserved occupations, focusing on anti-invasion preparations including patrols and static defences along the River Usk.[38] Nearby Sennybridge training area and the requisition of Mynydd Epynt in 1940—evicting around 200 residents to create a 30,000-acre artillery range—enabled intensive infantry and gunnery exercises for national forces, while the Brecknockshire Battalion provided drafts for active service and reinforced coastal defences.[39] The home front adapted via rationing and agricultural intensification, with the town's barracks sustaining employment in logistics and maintenance, mitigating broader industrial disruptions. Post-1945, the Infantry Battle School at Brecon emerged as a cornerstone of British Army training, building on wartime facilities at Dering Lines to deliver tactics, leadership, and combat courses for infantry from corporal to general ranks, processing thousands annually by the mid-20th century.[40] This institution, formalised in the late 1940s amid post-war restructuring, anchored Brecon's economy as a defence hub, offsetting civilian job losses. The 1962 closure of Brecon railway station to passengers—followed by goods traffic in 1964—as part of the Beeching rationalisation, severed key links to the Neath and Brecon line, accelerating the decline of freight-dependent trades and prompting a pivot toward service-oriented activities like military support and emerging tourism.[41] This shift underscored Brecon's resilience through sustained military investment amid national deindustrialisation.Geography

Location and Topography

Brecon lies in southeastern Powys, Wales, at the confluence of the Rivers Usk and Honddu, positioning it as a key valley settlement amid upland terrain.[42] The town's central area sits at coordinates 51°56′53″N 3°23′28″W, with elevations ranging from approximately 136 meters in lower sections to an average of 216 meters across the broader locale.[43][44] This positioning places Brecon fully within the boundaries of Bannau Brycheiniog National Park, designated in 1957 and covering 519 square miles of mountainous landscape, with the park's name officially reverting to its Welsh form in 2023.[45] The surrounding topography features the rugged Brecon Beacons range, characterized by steep escarpments and peaks rising to over 800 meters, which constrain settlement and route development to river valleys like that of the Usk.[45] This configuration has causally directed historical transport corridors through passes and along waterways, while the rivers' confluence elevates flood vulnerability in low-lying areas, as mapped in topographic surveys.[44] Proximity to the Sennybridge Training Area, situated about 13 kilometers north and encompassing over 12,400 hectares of restricted military land, further delineates land use patterns, limiting civilian development in adjacent uplands.[46]Climate and Environmental Features

Brecon experiences a temperate maritime climate characterized by mild, wet conditions influenced by its upland location in the Brecon Beacons. Average winter temperatures range from 4°C to 7°C, while summer highs typically reach 15°C to 18°C, with annual means decreasing by about 0.5°C per 100 meters of elevation gain due to topographic effects.[47] Annual precipitation averages around 1,200 mm, with peaks in autumn and winter; November often sees the highest monthly totals exceeding 80 mm, reflecting the region's exposure to Atlantic weather systems.[48] Historical records indicate natural variability, including wetter periods in the 18th and 19th centuries documented in Welsh archives, underscoring that extreme rainfall events predate modern anthropogenic influences.[49] The surrounding landscape features diverse habitats, including grasslands, heathlands, and moorlands, where military training activities on estates like Sennybridge contribute to environmental management by maintaining open terrain through controlled disturbance, which inhibits woody succession and supports species adapted to dynamic conditions.[50] The UK's Ministry of Defence oversees 190,000 hectares of such training land, implementing conservation measures that enhance biodiversity, such as habitat restoration for ground-nesting birds and invertebrates, resulting in higher populations of specialist flora and fauna compared to unmanaged areas.[50] These practices align with empirical observations that periodic human-induced disturbance can sustain ecological diversity in temperate uplands, countering narratives of uniform degradation.[51] The River Usk, flowing through Brecon, has a history of periodic flooding from channel capacity exceedance, with notable events in 1799, 1853, 2007, and 2020 recording peak levels that isolated communities and disrupted infrastructure. [52] Mitigation relies on engineering solutions, including flood risk management plans by Natural Resources Wales that prioritize structural defenses, river maintenance, and early warning systems over land-use restrictions, effectively reducing impacts in recent decades.[53] These approaches address fluvial dynamics empirically, recognizing floods as inherent to the catchment's hydrology rather than solely amplified by contemporary factors.[54]Demographics

Population Dynamics

The population of Brecon has exhibited modest growth and fluctuations over the past two centuries, as recorded in successive UK censuses. In 1841, the town's population stood at 5,609, encompassing the parishes of St. John's, St. Mary's, St. David's, and Christ's College.[35] This figure rose slightly to 5,975 by 1851, coinciding with early railway developments such as the Brecon and Llandovery Canal's influence on regional connectivity, before dipping to 5,634 in 1861 amid broader economic shifts in Breconshire. Subsequent decades saw an uptick to 6,251 in 1871 and a peak of 6,651 in 1881, potentially linked to expanded rail infrastructure including the Mid-Wales Railway's extension, followed by a decline to 5,960 in 1891 and stabilization at 6,012 in 1901.[35] By the 20th century, census figures reflected steady expansion, reaching 7,901 in 2001. This increased to 8,250 in the 2011 census and 8,254 in 2021, indicating near-stability with an annual change of approximately 0.0% over the 2011–2021 decade despite broader rural depopulation trends in Powys.[55] Peaks in population have historically correlated with influxes tied to military establishments, such as the barracks and training facilities established in the Victorian era and expanded post-World War II, which provided employment drawing residents to the area and countering out-migration from agriculture.[56] In the rural context of Powys, Brecon shares an aging demographic profile, with the county's proportion of residents aged 65 and over rising 22.3% between 2011 and 2021, outpacing national trends and accompanied by a 5.8% decline in the working-age population (15–64).[57] Net migration to Brecon has been influenced by employment opportunities, including sustained military presence at facilities like the Infantry Battle School, which sustains local residency amid otherwise subdued natural growth in this low-density region (743.5 persons per km² in 2021).[55][58]Socioeconomic Composition

According to the 2021 Census, Brecon's population of 8,093 residents is predominantly White, comprising 7,570 individuals or 93.6%, with Asian residents at 491 (6.1%), Black at 25 (0.3%), and other ethnic groups totaling under 0.5%.[55] This composition underscores the town's limited ethnic diversity, attributable to its rural setting in Powys, where immigration rates remain low compared to urban Wales.[59] Median earnings in Powys, encompassing Brecon, trail UK figures, with full-time male salaries at £35,700 and female at £28,700 as of 2024 data, versus UK medians exceeding £35,000 for males and £34,000 for females.[60] Local household incomes average £38,400 to £44,600 in Brecon-adjacent areas, ranking in the lower half nationally and reflecting dependence on agriculture, public administration, and military-related employment for economic ballast.[61] [62] Deprivation metrics indicate Brecon fares better than many Welsh locales; in the 2008 Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation (latest area-specific proxy available), zero Lower-layer Super Output Areas in Brecon and Radnorshire ranked among Wales's 10% most deprived, with 24% in the least deprived quartile.[63] Agricultural volatility contributes to pockets of income instability, yet public sector and defense jobs mitigate broader socioeconomic strain.Economy

Primary Sectors and Employment

Agriculture, forestry, and fishing represent a foundational primary sector in the Brecon area, with Powys as a whole supporting 8,600 jobs in these fields as of 2019, equivalent to roughly 14% of total workplace employment across 60,700 positions.[64] Sheep farming predominates due to the upland pastures of the surrounding Brecon Beacons, sustaining family-run operations and contributing to local self-reliance amid rural topography that limits diversification.[65][66] Military-related activities provide another core pillar, anchored by the nearby Sennybridge Training Area—the third largest in the United Kingdom—which generates direct and indirect employment through training exercises and support services.[67] In the Brecon and Radnorshire constituency, public administration and defence accounted for 2,000 employee jobs, or 8.7% of the 23,000 total, as of recent Nomis data.[68] This sector's stability, reinforced by ongoing Ministry of Defence commitments to maintain Army presence in Brecon, underpins economic resilience.[56] Retail, wholesale trade, and associated services fulfill the market town role, employing 3,000 workers (13% of jobs) in Brecon and Radnorshire, facilitating local commerce and distribution.[68] The area's claimant count stands at 2.7% (1,025 individuals), aligning with national lows and attributable in part to consistent defence expenditures offsetting rural vulnerabilities.[68] Historical canal infrastructure, including the Monmouthshire and Brecon Canal, once enabled modest logistics for agricultural goods, echoing a legacy of integrated transport in primary production.[69]Tourism and Recent Infrastructure Investments

Tourism in Brecon is predominantly driven by its position as a gateway to Bannau Brycheiniog National Park (formerly Brecon Beacons), featuring hiking trails, waterfalls, and outdoor activities that attract visitors seeking natural landscapes. The Monmouthshire and Brecon Canal, originating in Brecon Basin, contributes significantly to this sector, offering scenic boating, walking, and cycling routes voted among the UK's most beautiful waterways, with the canal alone generating £30 million in annual economic output and supporting approximately 1,000 jobs across its length.[70] Broader park-wide tourism yields over £126 million annually in local economic value, though specific Brecon attribution relies on its role as a central hub rather than isolated metrics.[71] Recent infrastructure investments emphasize pedestrian-friendly enhancements and tourism facilitation post-2023. In May 2025, Powys County Council secured additional Welsh Government funding for Brecon town centre streetscape improvements, focusing on prioritizing walkers amid ongoing community consultations that closed on March 30, 2025, with construction slated for early 2026.[72] This builds on nearly £7 million allocated under the Brecon and Radnorshire Strategic Town Centre Investment package for multiple projects aimed at regeneration.[73] Complementing these, a £5 million Welsh Government investment in July 2025 targets water pumping upgrades for the Monmouthshire and Brecon Canal to sustain navigability and boating tourism.[74] Controversial proposals, such as the £7 million development plan for Waterfall Country near Pontneddfechan—envisioning enhanced visitor facilities in the national park—faced local opposition over landscape alteration and overcrowding risks, despite council approval in early 2025 following funding success.[75] [76] Evaluations of return on investment remain preliminary, with visitor data from park surveys indicating sustained post-pandemic recovery but lacking granular ROI tied to these specific outlays, as broader Mid Wales tourism expenditure reached £1 billion directly in recent assessments without isolating Brecon's gains.[77]Military Significance

Historical Military Establishments

The Barracks in Brecon originated as an armaments store constructed in 1805 to support local militia needs during the Napoleonic Wars, with significant expansions occurring between 1842 and 1844 amid the Victorian era's military reforms and imperial commitments.[31] These additions transformed the site into a functional regimental complex, reflecting the British Army's strategic shift toward localized depots for recruitment, training, and administration to maintain readiness in response to colonial and European threats.[78] By 1873, under the Cardwell Reforms, the barracks were designated as the depot for the 24th Regiment of Foot (later the South Wales Borderers), housing two battalions and emphasizing territorial linkages to draw recruits from Wales while enabling rapid mobilization.[31] In 1881, following further localization, it became the permanent headquarters for the renamed South Wales Borderers, underscoring Brecon's role in sustaining infantry forces for operations in regions like Africa and Asia.[31] The establishment of the Sennybridge Training Area in 1939 marked a major expansion of military infrastructure around Brecon, as the War Office acquired approximately 12,400 hectares of Mynydd Epynt's rugged terrain for live-fire and maneuver exercises, compelled by the need for expansive, realistic training grounds amid rising European tensions.[79] During World War II, the area facilitated intensive preparations for infantry and armored units, leveraging the Beacons' topography to simulate defensive and assault scenarios, which proved vital for Allied operations given the site's isolation and natural cover.[80] Postwar, particularly in the Cold War era, developments included the construction of mock urban structures like the Cilieni village in the early 1980s, designed to replicate Eastern Bloc settlements for "Fighting in Built-Up Areas" (FIBUA) drills, addressing the strategic imperative of urban combat against potential Warsaw Pact advances in Europe.[81] Following a 2016 Ministry of Defence announcement to rationalize estates by closing Brecon Barracks by 2027, government commitments ensured the retention of key facilities, affirming their ongoing strategic value for infantry training in challenging terrains despite fiscal pressures.[82] This decision preserved the barracks' role as administrative hub and the Sennybridge range's capacity for large-scale exercises, rooted in the proven utility of Brecon's landscape for developing tactical proficiency without overseas dependencies.[83]Modern Training Facilities and Economic Contributions

The Infantry Battle School (IBS) at Brecon serves as the British Army's center for close combat training, delivering specialized courses for infantry officers, non-commissioned officers, and soldiers to enhance operational readiness. Annually, it equips over 3,500 personnel with tactical skills through demanding programs such as the Platoon Commanders' Battle Course and Platoon Sergeants' Battle Course, conducted in conjunction with the adjacent Sennybridge Training Area (SENTA). SENTA, the third-largest military training area in the United Kingdom spanning approximately 31,000 acres, supports live-fire exercises, maneuver training, and battle simulations essential for maintaining infantry proficiency amid evolving threats.[84][67][40] These facilities contribute to the local economy in Powys by generating direct employment at the IBS and SENTA, including roles for training area operatives, support staff, and contractors managed by organizations like Landmarc Support Services. The army camp at Sennybridge has long been recognized as a key employer in the area, sustaining jobs in maintenance, logistics, and ancillary services amid limited alternative opportunities in rural Mid Wales. Military personnel and visiting units further stimulate economic activity through expenditures on accommodation, supplies, and services in Brecon and surrounding communities, with the Ministry of Defence acknowledging such localized benefits from training estate operations in evidence to parliamentary inquiries.[85][86][87] Beyond immediate employment, the military's stewardship of SENTA preserves large tracts of land for training purposes, mitigating pressures for urban development and supporting rural land management practices that align with environmental objectives while bolstering national defense capabilities. This long-term allocation of Crown land prevents encroachment by alternative uses, maintaining the area's open character and indirectly aiding biodiversity efforts under MOD environmental policies. Overall, these contributions underscore the IBS and SENTA's dual role in fortifying UK security while providing sustained economic anchors in an otherwise agrarian Powys economy.[88][87]Criticisms and Environmental Debates

Criticisms of military training in the Brecon area, particularly at the Sennybridge Training Area within Bannau Brycheiniog (formerly Brecon Beacons) National Park, center on environmental disturbances such as noise pollution and potential soil erosion from vehicle maneuvers and infantry exercises. Local residents have reported excessive noise from artillery and small-arms fire, leading the Ministry of Defence to reduce training intensity by 30% at certain sites in response to complaints, as seen in adjustments to exercises involving international partners.[89][90] Inquiries into national park land use have highlighted a "fundamental conflict" between intensive military activities and public recreation, with concerns over habitat fragmentation and erosion in upland terrains used for live-fire drills.[91] Erosion risks arise from tracked vehicles and troop movements compacting peat soils, potentially exacerbating runoff in sensitive moorland ecosystems, though quantitative data on long-term degradation remains limited to site-specific MoD assessments rather than independent audits. Noise impacts extend to wildlife, with studies on similar UK training grounds noting disruptions to bird breeding patterns, though direct Brecon-specific avian surveys post-2010 show no population collapses attributable solely to military use.[92] Counterarguments emphasize military stewardship mitigating broader environmental pressures, as restricted access in training zones limits recreational trampling and overgrazing, preserving open landscapes akin to managed moors. The Ministry of Defence's environmental management framework, including habitat restoration and controlled burning to mimic natural cycles, has maintained biodiversity stability in Sennybridge, with monitoring reports indicating no net loss in key species like red grouse or blanket bog integrity since enhanced protocols in the early 2000s.[51] Local sentiment largely supports continued use, with protests rare and confined to historical displacements like the 1940 Epynt clearances rather than ongoing operations; no large-scale environmental actions have disrupted training since adaptations like reduced live-fire footprints following 2013 heat-related incidents.[93] These debates reflect a balance where military activities, while introducing localized stressors, contribute to landscape persistence by curbing alternative developments like intensified farming or tourism infrastructure, as acknowledged in national park planning documents prioritizing multi-use conservation.[94]Governance

Local Government Structure

Brecon is administered as a community within Powys, a unitary authority in Wales governed by Powys County Council, which holds responsibility for principal local services including education, highways, social care, and waste management. The council operates under statutory frameworks established by the Welsh Government, with Powys divided into electoral divisions where Brecon forms part of the broader authority's decision-making structure.[95] Brecon Town Council serves as the community's tier-one representative body, comprising 12 elected councillors who convene monthly meetings, excluding August and December recesses.[96] The council elects a mayor annually from among its members to preside over proceedings and represent the town ceremonially.[97] Committees, such as those for planning, finance, and amenities, address specific functions including reviewing planning applications forwarded from the Brecon Beacons National Park Authority and maintaining local assets like parks and allotments. Bylaws on local matters, such as public spaces, require approval from higher authorities but enable community-specific regulations.[97] Within Welsh devolution, powers over local government structure and operations rest with the Senedd, which has enacted legislation like the Local Government and Elections (Wales) Act 2021 granting councils general well-being powers to promote economic, social, environmental, and cultural advancement. This framework empowers Powys County Council and subordinate bodies like Brecon Town Council to deliver services in planning, housing, and community development, subject to national oversight. At the parliamentary level, Brecon falls within the Brecon, Radnor and Cwm Tawe constituency, represented by David Chadwick of the Liberal Democrats, who assumed office following the July 2024 general election and addresses constituency issues in the UK House of Commons.[98]Administrative Evolution

Brecon functioned as the county town of Brecknockshire, an administrative county established under the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542, handling county-level governance, quarter sessions, and markets from that period onward.[99] [100] The Local Government Act 1972 reorganized local authorities in England and Wales, abolishing Brecknockshire as an administrative county effective 1 April 1974, with the majority of its area, including Brecon, transferred to the newly formed county of Powys, which amalgamated parts of Brecknockshire, Montgomeryshire, and Radnorshire.[101] [100] This shift preserved Brecon's central role within the expanded Powys framework without altering its immediate municipal boundaries, though it ended the town's status as head of a standalone historic county.[102] Historically an assize town on the Wales circuit, Brecon accommodated visiting judges for superior criminal trials and civil disputes in the Shire Hall, a practice dating to at least the medieval period and formalized in the 19th century with the hall's construction.[32] The Courts Act 1971 terminated assizes nationwide effective 1972, redirecting major cases to permanent Crown Courts elsewhere, such as in Cardiff or Merthyr Tydfil, while Brecon's judicial facilities adapted to magistrates' courts for local petty sessions, summary trials, and youth proceedings. [103] This evolution reflected broader centralization of higher justice, reducing periodic judicial influxes to Brecon but maintaining basic local adjudication.[104]Political Controversies and Reforms

In January 2025, Powys County Council reported that its internal fraud team was investigating six staff members for potential irregularities, with inquiries potentially tracing back several years based on council statements.[105] [106] The probes formed part of wider efforts targeting Council Tax discounts and support claims, aiming to recover £1.329 million in identified overpayments, as detailed in quarterly governance reports.[105] Council leaders emphasized the investigations' role in enhancing financial oversight, though no charges had been filed by mid-2025, prompting calls from opposition councillors for clearer timelines and transparency.[107] A significant controversy emerged in early 2025 involving Powys Teaching Health Board, which proposed aligning waiting times for Powys residents treated in English NHS hospitals with slower Welsh targets to cut cross-border costs estimated at millions annually.[108] Critics, including local MPs and residents, argued the plan prioritized budgets over patient outcomes, potentially delaying urgent care amid already strained services.[109] The board scrapped the proposals on January 29, 2025, after public backlash and internal review, reaffirming commitment to equitable access while noting fiscal pressures from Welsh Government funding shortfalls.[108] [109] David Chadwick, Liberal Democrat MP for Brecon, Radnor and Cwm Tawe, voiced opposition to UK Labour government plans for mandatory digital IDs in October 2025, warning they could erode civil liberties by enabling unchecked surveillance without proven security gains.[110] [111] He highlighted privacy risks in a Westminster Hall debate, urging abandonment of the scheme amid constituent concerns over data centralization.[112] Supporters of the policy countered that voluntary digital verification already aids efficiency, but Chadwick's stance reflected broader Welsh Liberal Democrat resistance to perceived overreach.[110] Planning disputes in Brecon and surrounding areas have centered on affordable housing proposals clashing with Brecon Beacons National Park restrictions, which prioritize landscape preservation over development. In January 2024, Powys County Council refused outline permission for a single affordable home near Brecon, deeming it incompatible with the rural character despite acknowledged local shortages of 1,200 affordable units county-wide.[113] A similar bid in Bronllys, reapplied in June 2024 after initial rejection, faced opposition from park authorities citing visual and ecological impacts, illustrating tensions between housing needs and statutory protections under the Sandford Principle.[114] Local stakeholders, including developers and councils, advocate for policy reforms to permit modest infill developments, while environmental groups maintain strict controls are essential to prevent erosion of the park's 1,300-square-kilometer designated status.[113]Education

Primary and Secondary Schools

Brecon High School serves as the primary state secondary school for the town, accommodating approximately 500 pupils aged 11 to 16, with a focus on a broad curriculum including Welsh-medium provision.[115][116] The school has encountered significant operational challenges, including placement in Estyn special measures since 2014 due to inadequate leadership, teaching quality, and pupil outcomes identified in core inspections.[117] A 2019 Estyn report noted an inclusive ethos but persistent weaknesses in standards and progression, while a 2022 monitoring visit judged progress as insufficient against prior recommendations.[118][119] Financial difficulties have compounded these issues, with internal audits in 2020 revealing budgeting shortfalls and reserve overuse, contributing to broader Powys schools' deficits amid enrollment declines.[120][121] As of January 2025, the school remained in special measures despite some monitoring improvements, though Powys County Council anticipated Estyn's removal of this status by December 2025 based on ongoing recovery efforts.[122][123] Primary education in Brecon is provided by several institutions, including Ysgol Golwg Pen y Fan, formed in 2023 from the merger of Cradoc Primary, Mount Street Infants, and Mount Street Juniors to address sustainability amid falling pupil numbers across Powys.[124] Ysgol Penmaes offers specialist provision for pupils aged 3 to 19 with additional learning needs, emphasizing individualized support in a Welsh-medium context.[125] Other key primaries include Priory Church in Wales Primary School, serving local children with a faith-based curriculum.[126] Enrollment declines have intensified pressures, with Powys schools collectively facing a £3 million funding shortfall in 2024 due to reduced pupil intake and rising costs, leading to reserve drawdowns exceeding £5.8 million.[127] A specific manifestation of these trends occurred in October 2025, when Powys County Council proposed closing one campus of Ysgol Golwg Pen y Fan—opened just a year prior—owing to plummeting pupil numbers that rendered it unsustainable, exacerbated by the loss of on-site breakfast and after-school care services.[128][129][130] This reflects wider Estyn concerns over Powys education services, including leadership weaknesses and site security issues highlighted in a March 2025 inspection, amid fears of declining secondary standards county-wide.[131][132]Higher Education and Vocational Training

Brecon lacks a traditional university campus, with residents typically accessing higher education through nearby institutions or specialized programs tied to the local economy. Brecon Beacons College, part of the NPTC Group of Colleges, serves as the primary further education provider in the town, offering vocational qualifications in areas such as business, tourism management, and health and social care at facilities including The CWTCH and Y Gaer.[133] These courses emphasize practical skills relevant to tourism, a key sector in the Bannau Brycheiniog National Park region, including event management and hospitality operations.[133] Adjacent to Brecon, Black Mountains College provides alternative higher education through its BA (Hons) in Sustainable Futures, focusing on ecological thinking, regenerative agriculture, and systems change, with further education diplomas in regenerative horticulture and agroecology.[134] These programs, delivered at sites like Troed-yr-Harn farm near Talgarth, equip students with hands-on skills in sustainable land management and community resilience, aligning with agricultural and eco-tourism demands in rural Powys.[135] Enrollment emphasizes small cohorts for personalized training, with applications for 2026 intakes prioritizing interdisciplinary vocational outcomes over conventional academic paths.[136] The Infantry Battle School at Dering Lines in Brecon functions as a de facto advanced training hub for local recruits entering military service, delivering specialized infantry skills, leadership, and tactical proficiency to over 3,000 personnel annually, including many from surrounding communities.[40] While not open to civilians, participation by Powys residents provides transferable vocational expertise in discipline, navigation, and high-stakes decision-making, often leading to defense-related trades or security roles post-service.[40] This military pathway supplements formal college offerings by fostering practical competencies in a region where agriculture and tourism intersect with national defense infrastructure.[56]Transport

Road Networks and Bridges

Brecon's road infrastructure centers on the A40 trunk road, which bypasses the town center and provides essential east-west connectivity across southern Wales. The A40 intersects with the north-south A470 at a junction east of Brecon, enabling efficient links to major cities including Cardiff approximately 40 miles southeast via the A470 and Swansea to the southwest through the A40's route via the Brecon Beacons.[137] This configuration supports regional traffic flow while directing through-traffic away from the historic town core, with the bypass constructed to mitigate congestion and flood-related disruptions observed in earlier alignments.[138] The Usk Bridge, Brecon's oldest crossing over the River Usk, exemplifies historic engineering adapted to the area's flood-prone environment. Built in 1563 of stone to replace a structure destroyed by flooding in 1535, the multi-arch bridge originally carried the A40 before being redesignated to the B4601 following the town's bypass development.[139] Repairs in 1772 addressed wear from repeated inundations, underscoring the bridge's resilience through centuries of high river flows, with records noting severe floods impacting Usk crossings as recently as the 1979 event that challenged nearby infrastructure.[139][138] Maintenance efforts continue to prioritize flood mitigation, given the River Usk's documented history of overflow affecting Brecon's low-lying approaches. In response to growing traffic and parking pressures, Powys County Council implemented targeted restrictions in 2025, including double yellow lines along key village roads near Brecon such as in Llangynidr. These measures aim to curb obstructive parking on strategic routes like the A40 feeder paths, improving safety and flow amid rising visitor numbers to the Beacons.[140][141] Local consultations highlighted inconsiderate vehicle placement blocking emergency access and narrowing carriageways, prompting these enforceable demarcations effective from October 2025.[142]Canals and Waterways

The Brecknock and Abergavenny Canal, forming the northern section of the modern Monmouthshire and Brecon Canal, received parliamentary authorization in 1793 to transport lime, coal, iron, and other industrial freight from inland quarries and mines to coastal ports via connection to the Monmouthshire Canal.[29] Construction began in 1797 under engineers including John Duncombe and Charles Kyan, reaching Brecon Basin by 1800 after overcoming steep gradients through contoured routing along the Usk Valley.[143] Full linkage to the Monmouthshire Canal at Pontymoile occurred in 1812, enabling 35 miles (56 km) of narrow-beam navigation suited to horse-drawn barges carrying up to 20 tons per load.[144] Engineering highlights near Brecon include Brynich Lock, a broad single-chamber structure operational since the early 1800s, and the canal's contour-hugging design minimizing earthworks while incorporating feeder reservoirs for water supply amid the hilly Brecon Beacons terrain.[145] Towpaths, originally laid for towing animals, span the full length and feature stone or brick edging in preserved sections, with aqueducts and minor tunnels like the short Ashford cutting facilitating valley traversal without excessive locks in the Brecon approach.[146] These elements reflect early 19th-century hydraulic engineering prioritizing efficiency for freight over passenger use, with water levels maintained via gravity-fed pounds and waste weirs. By the mid-20th century, commercial freight ceased due to rail and road competition, prompting restoration efforts from the 1960s onward by volunteer groups and the Canal & River Trust, shifting the canal's role to heritage recreation.[147] Today, the navigable 35-mile stretch supports leisure boating via hire fleets based at Brecon Basin, requiring licenses for narrowboats up to 57 feet, with annual usage focused on short cruises amid scenic rural isolation featuring only 6 working locks overall.[146] Towpaths host over 3 million annual visits for walking and cycling, generating approximately £17 million in local economic activity through boater expenditures and tourism draw, per 2007 assessments updated for sustained post-industrial viability.[147] Maintenance challenges, including water abstraction limits under 21st-century regulations, underscore ongoing reliance on rainfall and trust interventions for sustained recreational access.[148]Rail History and Current Access

The Hereford, Hay and Brecon Railway, authorised in 1860 and opened progressively from 1863 to 1865, established a 36-mile route linking Hereford with Brecon via Hay-on-Wye, facilitating passenger and freight transport in rural Powys.[149] The line, initially independent, was absorbed by the Midland Railway in 1876, which integrated it into broader networks but struggled with low traffic volumes typical of branch lines.[149] Complementing this was the Neath and Brecon Railway, opened between 1862 and 1869, which connected Brecon southward to Neath and colliery districts, handling both passenger services and mineral traffic until its decline.[150] Passenger services on the Hereford, Hay and Brecon line ceased on 31 December 1962 as part of the Beeching cuts, which targeted unprofitable rural routes amid British Railways' financial losses exceeding £300 million annually by 1961.[149] [151] Freight operations ended in 1964, with the track fully dismantled shortly thereafter, severing Brecon's direct rail links to the north.[151] Similarly, the Neath and Brecon line lost all passenger traffic in October 1962, with the section north of Craig-y-Nos closing entirely that year, reflecting broader rationalisation under the 1963 Reshaping of British Railways report that recommended eliminating 5,000 miles of track nationwide.[150] These closures, driven by declining patronage—often fewer than a dozen daily passengers on terminal sections—left Brecon isolated from the national network.[152] Today, Brecon lacks an operational railway station, with the nearest services on the Heart of Wales Line, a preserved scenic route from Shrewsbury to Swansea via stations such as Builth Road (8 miles east) and Llandrindod Wells (15 miles northeast).[153] Access relies on bus substitutions, including TrawsCymru T4 services linking Brecon to Llandrindod Wells (journey time approximately 45 minutes, four daily departures) and connections to Builth Road for onward trains.[154] Post-1960s closures have sustained reduced connectivity, increasing dependence on road transport and contributing to economic challenges in rural Powys, where rail revival proposals have not materialised due to high restoration costs estimated over £100 million for similar branch lines.[153]Culture and Society

Local Traditions and Events

Brecon's market heritage, established by royal charter in 1556, manifests in ongoing traditions of local trade and produce fairs. The town continues to host weekly markets in Brecon Market Hall, a custom tracing back to medieval times when it served as a central hub for livestock and goods exchange in south Wales.[1] An annual highlight is the Brecon Beacons Food Festival, held on the first Saturday of October, which gathers over 50 regional producers to showcase traditional Welsh foods like cheeses, meats, and baked goods, emphasizing sustainable farming practices rooted in the area's agricultural economy.[155][156] The town's military connections, bolstered by the Infantry Battle School and other training facilities in the surrounding Brecon Beacons, underpin events that honor service traditions. Annually, Brecon Town Council facilitates a Gurkha parade, enabling the Gurkha Wing (Mandalay Company) of the 3rd Battalion, Royal Gurkha Rifles, to march through the streets under rights granted by honorary citizenship, commemorating their historical ties to the region dating to World War II deployments.[157] The biennial Cambrian Patrol, organized by the British Army's 160th Infantry Brigade, challenges international teams with a 64 km endurance march across the Beacons' terrain, replicating real-world infantry patrols and drawing record participation in recent years, such as 2025's event from October 3 to 12.[158] Customs linked to nonconformist history include community assemblies influenced by the Plough Chapel, founded in 1699 as one of Wales' earliest Independent chapels following the Toleration Act. While primarily architectural, this site symbolizes the town's role in early dissenting movements, where isolated farm gatherings evolved into structured market-town conventions that reinforced self-reliance and mutual aid among nonconformists, though formalized events from this era have largely integrated into broader civic life.[159][160]Arts, Media, and Community Life

The Brecon Community Swap Shop, established in October 2024 at Priory Church in Wales Primary School, facilitates the exchange of clothing, school uniforms, gym kits, and other essentials to address cost-of-living challenges in the rural area.[161] Funded by the Green Man Trust, the initiative operates year-round and serves the broader community, including families facing financial pressures from uniform costs, earning recognition in the Senedd for its practical support.[162] Complementing such efforts, the same school installed a book vending machine in January 2024, stocked with reading materials via a £2,000 grant from the Green Man Trust to encourage literacy among pupils and residents.[163] In the arts domain, Theatr Brycheiniog functions as a central hub for performing arts and community gatherings, presenting theatre, music, dance, and gallery exhibitions such as the embroidered Red Dress installation in recent years.[164] Y Gaer, a combined museum, art gallery, and library, hosts displays of local and regional artworks, including historical pieces tied to Breconshire's landscape traditions, while fostering creative learning spaces.[165] Venues like Brecon Story at the canal basin further support diverse artistic outputs, from live performances to heritage storytelling events.[166] Local media outlets, including the Brecon & Radnor Express and County Times, deliver coverage tailored to rural Powys dynamics, such as community funding allocations—like the £20,000 Anti-Poverty Locality Fund in September 2025 supporting arts and social projects—and everyday concerns like school closures or traffic disruptions, providing granularity often absent in national urban-oriented reporting.[167][168] These publications emphasize verifiable local data over broader narratives, aiding community cohesion through detailed accounts of initiatives like wellbeing programs and intergenerational activities.[169]Religion

Historical Christian Foundations

Brecon's Christian heritage originates from pre-Norman Celtic worship, particularly at the site now occupied by Brecon Cathedral, where an early Celtic church preceded Norman constructions. In 1093, Bernard de Neufmarché, the Norman lord of Brecon, founded the Benedictine Priory of St John the Evangelist on this elevated location above the River Honddu, establishing it as a monastic house with an initial church structure integrated into the priory complex.[170][15] The priory church underwent major rebuilding and Gothic-style extensions during the 13th century, incorporating features such as the nave and incorporating surviving elements like the original font from the 12th century. This development solidified its role as a central religious institution, serving both the monastic community and local parishioners until the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1537, when it transitioned to function as the parish church of St John the Evangelist.[15][170] St David's Church in the Llanfaes suburb represents another foundational Christian site, with records indicating its presence since at least the 1180s as a medieval parish church dedicated to the Welsh patron saint David. The original structure endured until collapsing in 1852, prompting a rebuild in 1859 on or adjacent to the historic location, thereby maintaining continuity of worship at this longstanding ecclesiastical point.[12][171]Contemporary Religious Landscape