Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Millettia laurentii

View on Wikipedia

| Millettia laurentii | |

|---|---|

| |

| Tree in flower | |

| |

| Tangentially-sawn wood | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae |

| Subfamily: | Faboideae |

| Genus: | Millettia |

| Species: | M. laurentii

|

| Binomial name | |

| Millettia laurentii | |

| Wenge | |

|---|---|

| Hex triplet | #645452 |

| sRGBB (r, g, b) | (100, 84, 82) |

| HSV (h, s, v) | (7°, 18%, 39%) |

| CIELChuv (L, C, h) | (37, 10, 20°) |

| Source | [1] |

| B: Normalized to [0–255] (byte) | |

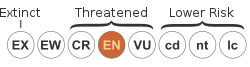

Millettia laurentii is a legume tree from Africa and is native to the Republic of Congo, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Cameroon, Gabon and Equatorial Guinea. The species is listed as "endangered" in the IUCN Red List, principally due to the destruction of its habitat and over-exploitation for timber.[1] Wenge, a dark coloured wood, is the product of Millettia laurentii. Other names sometimes used for wenge include faux ebony, dikela, mibotu, bokonge, and awong. The wood's distinctive colour is standardised as a "wenge" colour in many systems.

Wood

[edit]Wenge (/ˈwɛŋɡeɪ/ WENG-gay) is a tropical timber, very dark in colour with a distinctive figure and pattern. The wood is heavy and hard, suitable for flooring and staircases.

Several musical instrument makers employ wenge in their products. Mosrite used it for bodies of their Brass Rail models. Ibanez and Cort use it for the five-piece necks of some of their electric basses. Warwick electric basses use FSC sourced wenge for fingerboards and necks as of 2013. It is also used by Yamaha as the centre ply of their Absolute Hybrid Maple drums.[2]

The wood is popular in segmented woodturning because of its dimensional stability and colour contrast when mixed with lighter woods such as maple. This makes it especially sought after in the manufacture of high-end wood canes and chess boards.

The wood is sometimes used in the making of archery bows, particularly as a laminate in the production of flatbows. It can also be used in the making of rails or pin blocks on hammered dulcimers.

The wood may also be used for kendamas. Though a ken could be made entirely out of wenge, it's generally used to substitute a portion of the big/small cups[3] while the rest of the ken is made out of a softer, less dense wood. This concentration of weight in the big and/or small cup facilitates balance tricks such as lunars.

Health hazards

[edit]The dust produced when cutting or sanding wenge can cause dermatitis similar to the effects of poison ivy and is an irritant to the eyes. The dust also can cause respiratory problems and drowsiness.[citation needed] Splinters are septic, similar to those of greenheart (the wood of Chlorocardium rodiei).

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Millettia laurentii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1998 e.T33219A9767710. African Regional Workshop (Conservation & Sustainable Management of Trees, Zimbabwe, July 1996). 1998. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1998.RLTS.T33219A9767710.en.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Absolute Hybrid Maple - Acoustic Drum Sets - Drums - Musical Instruments - Products - Yamaha United States". Yamaha United States. Yamaha Corporation of America. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

Hybrid Maple Shell (center Wenge ply)

- ^ youtube.com

Further reading

[edit]- Baker, Mark (2004). Wood for Woodturners. Sussex: Guild of Master Craftsmen Publications. ISBN 1-86108-324-6.