Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Xenobot

View on Wikipedia| Xenobot | |

|---|---|

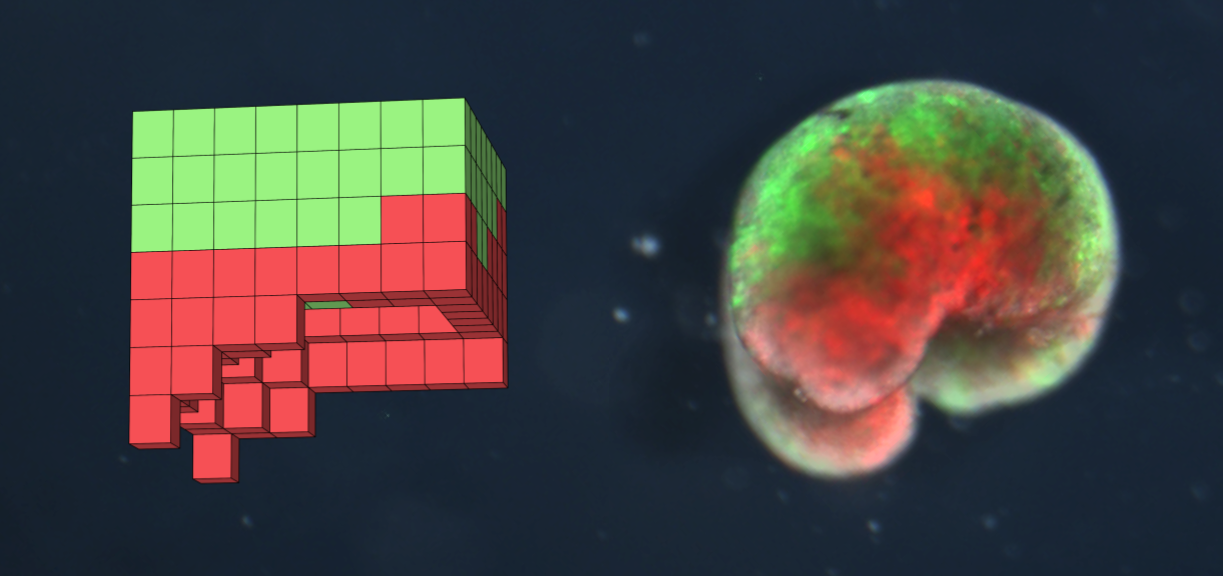

A xenobot design discovered in simulation (left) and the deployed organism (right) built from frog skin (green) and heart muscle (red) | |

| Industry | Robotics, Synthetic biology |

| Application | Medicine, environmental remediation |

| Dimensions | Microscale |

| Fuel source | Nutrients |

| Self-propelled | Yes |

| Components | Frog cells |

| Inventor | Sam Kriegman, Douglas Blackiston, Michael Levin, Josh Bongard |

| Invented | 2020 |

Xenobots, named after the clawed frog (Xenopus laevis),[1] are synthetic lifeforms that are designed by computers to perform some desired function and built by combining together different biological tissues.[1][2][3][4][5][6] There is debate among scientists whether xenobots are robots, organisms, or something else entirely.

Existing xenobots

[edit]The first xenobots were built by Douglas Blackiston according to blueprints generated by an AI program, which was developed by Sam Kriegman.[3]

Xenobots built to date have been less than 1 millimeter (0.04 inches) wide and composed of just two things: skin cells and heart muscle cells, both of which are derived from stem cells harvested from early (blastula stage) frog embryos.[7] The skin cells provide rigid support and the heart cells act as small motors, contracting and expanding in volume to propel the xenobot forward. The shape of a xenobot's body, and its distribution of skin and heart cells, are automatically designed in simulation to perform a specific task, using a process of trial and error (an evolutionary algorithm). Xenobots have been designed to walk, swim, push pellets, carry payloads, and work together in a swarm to aggregate debris scattered along the surface of their dish into neat piles. They can survive for weeks without food and heal themselves after lacerations.[2]

Other kinds of motors and sensors have been incorporated into xenobots. Instead of heart muscle, xenobots can grow patches of cilia and use them as small oars for swimming.[8] However, cilia-driven xenobot locomotion is currently less controllable than cardiac-driven xenobot locomotion.[9] An RNA molecule can also be introduced to xenobots to give them molecular memory: if exposed to specific kind of light during behavior, they will glow a prespecified color when viewed under a fluorescence microscope.[9]

Xenobots can also self-replicate. Xenobots can gather loose cells in their environment, forming them into new xenobots with the same capability.[10][11][12]

Potential applications

[edit]Currently, xenobots are primarily used as a scientific tool to understand how cells cooperate to build complex bodies during morphogenesis.[1] However, the behavior and biocompatibility of current xenobots suggest several potential applications to which they may be put in the future.

Xenobots are composed solely of frog cells, making them biodegradable and environmentally friendly robots. Unlike traditional technologies, xenobots do not generate pollution or require external energy inputs during their life-cycle. They move using energy from fat and protein naturally stored in their tissue, which lasts about a week, at which point they simply turn into dead skin cells.[2] Additionally, since swarms of xenobots tend to work together to push microscopic pellets in their dish into central piles,[2] it has been speculated that future xenobots might be able to find and aggregate tiny bits of ocean-polluting microplastics into a large ball of plastic that a traditional boat or drone could gather and bring to a recycling center.

In future clinical applications, such as targeted drug delivery, xenobots could be made from a human patient’s own cells, which would virtually eliminate the immune response challenges inherent in other kinds of micro-robotic delivery systems. Such xenobots could potentially be used to scrape plaque from arteries, and with additional cell types and bioengineering, locate and treat disease.

Gallery

[edit]-

One hundred computer-designed blueprints for a walking organism composed of passive (cyan) and contractile (red) voxels.

-

AI methods automatically design diverse candidate lifeforms in simulation (top row) to perform some desired function, and transferable designs are then created using a cell-based construction toolkit to realize living systems (bottom row) with the predicted behaviors.

-

A tall quadruped xenobot

-

The manufactured organism is layered with heart muscle (now glowing red). AI optimized the shape of the organism and the location of its muscle to produce forward movement.

-

A manufactured organism with two muscular hind limbs was the most robust and energy-efficient configuration of passive (epidermis; green) and contractile (cardiac; red) tissues found by the computational design algorithm.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Meet Xenobot, an Eerie New Kind of Programmable Organism". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028.

- ^ a b c d Kriegman, Sam; Blackiston, Douglas; Levin, Michael; Bongard, Josh (13 January 2020). "A scalable pipeline for designing reconfigurable organisms". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 117 (4): 1853–1859. Bibcode:2020PNAS..117.1853K. doi:10.1073/pnas.1910837117. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 6994979. PMID 31932426.

- ^ a b Sokol, Joshua (2020-04-03). "Meet the Xenobots: Virtual Creatures Brought to Life". The New York Times.

- ^ Sample, Ian (2020-01-13). "Scientists use stem cells from frogs to build first living robots". The Guardian.

- ^ Yeung, Jessie (2020-01-13). "Scientists have built the world's first living, self-healing robots". CNN.

- ^ "A research team builds robots from living cells". The Economist.

- ^ Ball, Philip (25 February 2020). "Living robots". Nature Materials. 19 (3): 265. Bibcode:2020NatMa..19..265B. doi:10.1038/s41563-020-0627-6. PMID 32099110.

- ^ "Living robots made from frog skin cells can sense their environment". New Scientist.

- ^ a b Blackiston, Douglas; Lederer, Emma; Kriegman, Sam; Garnier, Simon; Bongard, Joshua; Levin, Michael (31 March 2021). "A cellular platform for the development of synthetic living machines". Science Robotics. 6 (52): 1853–1859. doi:10.1126/scirobotics.abf1571. PMID 34043553. S2CID 232432785.

- ^ Kriegman, Sam; Blakiston, Douglas; Levin, Michael; Bongard, Josh (7 December 2021). "Kinematic self-replication in reconfigurable organisms". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 118 (49). Bibcode:2021PNAS..11812672K. doi:10.1073/pnas.2112672118. PMC 8670470. PMID 34845026. S2CID 244769761.

- ^ "These living robots made of frog cells can now reproduce, study says". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2021-12-01.

- ^ "Team Builds First Living Robots That Can Reproduce". November 29, 2021. Retrieved December 1, 2021.

External links

[edit]- Webpage summarizing and linking to all of the xenobot papers

- Xenobot Lab website

- "These Researchers Used A.I. to Design a Completely New 'Animal Robot'" Video on YouTube from Scientific American