Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Yelang

View on Wikipedia

| Yelang | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 夜郎 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

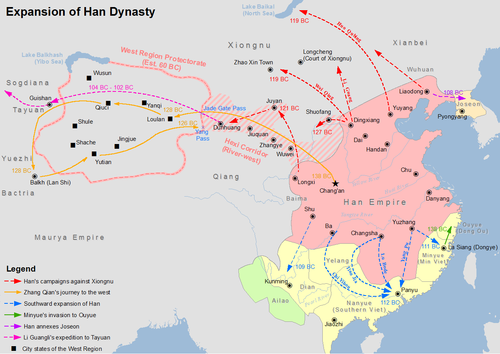

Yelang, also Zangke, was an ancient political entity first described in the 3rd century BC in what is now western Guizhou province, China. It was active for over 200 years.[1] The state is known to modern Chinese from the idiom, "Yelang thinks too highly of itself" (Chinese: 夜郎自大; pinyin: Yèláng zì dà; lit. 'Yelang self-aggrandizes').[2] It was absorbed by the Han Dynasty in 111 BC with the conquest of Nanyue, after an attempted conquest by the former Qin Dynasty.

Name

[edit]The inhabitants of Yelang called themselves Zina. This may be source of the Sanskrit word Cīna (चीन). The English word China is derived from this Sanskrit word.[2]

Geography

[edit]Expanse

[edit]

The Yelang were believed to have been an alliance of agricultural tribes covering parts of modern-day Guizhou, Hunan, Sichuan and Yunnan.[3]

Location

[edit]The ancient Chinese historian Sima Qian described Yelang located west of the Mimo and Dian, south of Qiongdu (in what is now southern Sichuan), and east of the nomadic Sui and Kunming.[4] Some people have identified the seat of the kingdom as Bijie (Chinese: 畢節) in today's Liupanshui area, in modern Guizhou province, whilst others suggest the capital moved throughout the region over time.[5]

Culture

[edit]Subsistence

[edit]The Yelang were primarily a confederation of agricultural farming tribes.[6]

Appearance and dress

[edit]Yelang people wore their hair up[6] and decorated themselves with jewellery such as bracelets and necklaces.

Material culture

[edit]Archaeologists have retrieved relics from Yelang graves including "bronze swords, U-shaped bronze hairclips, turquoise bracelets and jade necklaces",[1] as well as "various bronze, porcelain and stone vessels visibly different from those belonging to other cultures studied in China, like the Han, Dian and Bashu cultures".[6]

Burial rites

[edit]Tomb excavations show a unique burial custom in some Yelang tombs, in which the head of the deceased is placed into a bronze pot. This custom is unknown elsewhere in China.[6]

Military

[edit]According to Chinese records the Yelang had strong armies.[6]

Government

[edit]In 2007 a Miao man publicly disclosed his possession of an ancient seal, said to be that of the Yelang kingdom, and claimed to be the 75th generation descendant of the King of Yelang.[7]

Political relations

[edit]Warring States

[edit]In the early third century BCE, the state of Chu sent Zhuang Qiao to Yelang at the head of a military expedition to prevent the state of Qin from annexing these kingdoms. After negotiating these alliances with the state of Ba, who helped Zhuang Qiao negotiate passage through the state of Bi to reach Yelang. Yelang also accepted the terms of the agreement and Zhuang Qiao went further west to the Lake Dian region. However, in 281 BCE the Qin state sent Sima Cuo to intercept this threat to its interests and attacked Ba, eventually persuading Ba, Bi and Yelang to switch to alliances with the Qin.[8]

Nanyue

[edit]Yelang had a close relationship with the Nanyue ("Southern Yue") kingdom and used the Zangke River (now known as the Beipan River) as a means of international transportation.[9] The kingdom of Yelang declared their allegiance to Nanyue rule from the start of 183 BC until the end of 111 BC.

The Yi people may be modern-day descendants of the Yelang kingdom.[10]

In Chinese culture

[edit]Yelang is best known to modern Chinese because of an incident said to have occurred in the 120s BC. According to the story the king of Yelang, convinced that his kingdom was the greatest in all the world, inquired rhetorically of the Han emperor's envoy, "Which is greater, Yelang or Han?" This gave rise to the Chinese idiom, "Yelang thinks too highly of itself" (Chinese: 夜郎自大; pinyin: Yèláng zì dà). Other sources suggest that Yelang's king was simply copying an earlier statement by a ruler of the adjacent Kingdom of Dian.[11]

Other Chinese sources describe the Yelang people as possessing supernatural powers.[6]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Ancient Sites Open Windows on the Past". China Daily. 12 April 2002. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- ^ a b Wade, Geoff, "The Polity of Yelang and the Origin of the Name 'China'", Sino-Platonic Papers, No. 188, May 2009.

- ^ Gao, Wenchuan (January 2005). "Xinhuang County, the Site of Ancient Yelang Kingdom". China Pictorial. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- ^ Jacques Gernet (1996). A history of Chinese civilization. Cambridge University Press. p. 124. ISBN 0-521-49781-7. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

tien kingdom k'un-ming 1956.

- ^ 古国沉睡湖南沅陵?--打探"夜郎国"的秘密 (in Chinese). Beijing Youth Daily. 26 April 2001. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

贵州民族学院的王子尧教授告诉记者,从研究来看,夜郎的国都好像到处都是,除了沅陵、广顺、茅口等3个地方,牵涉到贵州省境的还有安顺、镇宁、关岭、贞丰、桐梓、贵阳、石阡、黄平、铜仁和云南省的宣威、沾益、曲靖,以及湖南省的麻阳等地方。于是有的学者就独辟蹊径,指出:既然在各地都发现有相关文物,证明该地为夜郎古都,这是否说明夜郎都邑处在一个不断变迁的过程,没有一个固定的地点。

- ^ a b c d e f "Chinese Archeologists Search for Clues on Lost Kingdom". People's Daily Online. 25 October 2002. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- ^ "Seal of ancient king made public". CRI.cn. 1 November 2007. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- ^ John Herman (2009). "The Kingdoms of Nanzhong China's Southwest Border Region Prior to the Eighth Century". T'oung Pao. 95 (4): 241–286.

- ^ Yang, Bin. "3". Between Winds and Clouds: The Making of Yunnan, Second Century BCE to Twentieth Century CE (Project Gutenberg Online ed.).

- ^ S.P. Chen (Jan 2005). "The Yelang Kingdom and the Yi People", Journal of Guizhou University For Nationalities, College of Cultural Communication de l'Université de Guizhou, Guiyang. Download links: 1 Archived 29 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Huo, Newmann (10 March 2005). "Relics reveal the mystery of Dian Kingdom". Shenzhen Daily online edition via Guangdong Culture News. Retrieved 19 August 2010.