Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Minyue

View on WikipediaKey Information

| Minyue | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 閩越 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 闽越 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

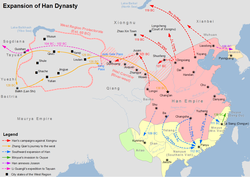

Minyue (Chinese: 閩越; Pinyin: Mǐnyuè, Mínyuè) was an ancient kingdom in what is now the Fujian province in southern China[a]. It was a contemporary of the Han dynasty, and was later annexed by the Han empire as the dynasty expanded southward. The kingdom existed approximately from 306 BC to 110 BC.[2]

History

[edit]

Foundation

[edit]

Both Minyue and Dong'ou were founded by the royal family of Yue that fled after being defeated by Chu and Qi in 334 BC. When the Qin dynasty fell in 206 BC, the Hegemon-King Xiang Yu did not make Zou Wuzhu and Zou Yao kings. For that reason, they refused to support him and instead joined Liu Bang in attacking Xiang Yu. When Liu Bang won the war in 202 BC, he made Zou Wuzhu king of Minyue and in 192 BC, he made Zou Yao king of Dong'ou (Eastern Ou).[3]

In 154 BC, Liu Pi King of Wu, revolted against the Han and tried to persuade Minyue and Dong'ou to join him. The king of Minyue refused but Dong'ou sided with the rebels. However, when Liu Pi was defeated and fled to Dong'ou, they killed him to appease the Han, and therefore escaped any retaliation. Liu Pi's son, Liu Ziju, fled to Minyue and worked to incite a war between the Minyue and Dong'ou.[3]

Wars against other countries

[edit]Attack on Dong'ou

[edit]In 138 BC, Minyue attacked Dong'ou and besieged their capital. Dong'ou managed to send someone to appeal for help from the Han. Opinions at the Han court were mixed on whether or not to help Dong'ou. Grand commandant Tian Fen was of the opinion that the Yue constantly attacked each other and it was not in the Han's interest to interfere in their affairs. Palace counsellor Zhuang Zhu argued that to not aid Dong'ou would be to signal the end of the empire just like the Qin. A compromise was made to allow Zhuang Zhu to call up troops, but only from Kuaiji Commandery, and finally an army was transported by sea to Dong'ou. By the time the Han forces had arrived, Minyue had already withdrawn its troops. The king of Dong'ou no longer wished to live in Dong'ou, so he requested permission for the inhabitants of his state to move into Han territory. Permission was granted and he and all his people settled in the region between the Changjiang (Yangtze) and Huai River.[3][4]

Invasion of Nanyue, defeat by Han and resettlement

[edit]In 137 BC, Minyue invaded Nanyue. An imperial army was sent against them, but the Minyue king was murdered by his brother Zou Yushan, who sued for peace with the Han. The Han enthroned Zou Wuzhu's grandson, Zou Chou, as king. However, after the Han envoy left, Zou Yushan also proclaimed himself king without the consent of the Han Emperor Wu. The emperor was informed of Yushan's actions, and recognized him as king of Dongyue instead of ordering a second invasion, deeming it too troublesome to punish Yushan. As a result, there were two kings coexisting in Minyue.[5][4][6]

In 112 BC, Nanyue rebelled against the Han. Zou Yushan pretended to send forces to aid the Han against Nanyue, but secretly maintained contact with Nanyue and only took his forces as far as Jieyang. Han general Yang Pu wanted to attack Minyue for their betrayal; however, the emperor felt that their forces were already too exhausted for any further military action, so the army was disbanded. The next year, Zou Yushan learned that Yang Pu had requested permission to attack him and saw that Han forces were amassing at his border. Zou Yushan then proclaimed himself Emperor of Dongyue[7] and made a preemptive attack against the Han, taking Baisha, Wulin, and Meiling, killing three commanders. In the winter, the Han retaliated with a multi-pronged attack by Han Yue, Yang Pu, Wang Wenshu, and two Yue marquises. When Han Yue arrived at the Minyue capital, the Yue native Wu Yang rebelled against Zou Yushan and murdered him. Wu Yang was appointed by the Han as marquis of Beishi. Han Emperor Wu felt it was too much trouble to occupy Minyue, as it was a region full of narrow mountain passes. He commanded the army to evict the region and resettle the people between the Changjiang (Yangtze) and Huai River. Legend has it that this left the region (modern Fujian) a deserted land.[8][9]

An ancient stone city located in the inner mountains of Fujian is said to have been the Minyue capital. The nearby tombs show the same funerary tradition as Yue state tombs in Zhejiang Province.

Culture

[edit]The indigenous Minyue of Fujian province had customs similar to those of some of the Taiwanese indigenous people, such as snake totemism, short hair-style, tattooing, teeth pulling, pile-dwellings, cliff burials, and uxorilocal post-marital residences. Perhaps the Taiwan aborigines were also Minyue people, derived in ancient times from the southeast coast of mainland China, as suggested by linguists Li Jen-Kuei and Robert Blust. It is suggested that in the southeast coastal regions of China, there were many sea nomads during the Neolithic era and that many spoke ancestral Austronesian languages, and were skilled seafarers.[10] In fact, there is evidence that an Austronesian language was still spoken in Fujian as late as 620 AD.[11]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Much of the present-day Fujian Province is controlled by the People's Republic of China (PRC), while the Republic of China (ROC) government based in Taipei retained control of Kinmen and Matsu islands, as part of the nominal Fuchien (Fukien) Province, albeit in a different spelling.

References

[edit]- ^ 《福建历代人口论考》,陈景盛,福建人民出版社,1991年8月

- ^ 《战国史》,杨宽,Shanghai People's Press,2016年7月

- ^ a b c Watson 1993, p. 220-221.

- ^ a b Whiting 2002, p. 145.

- ^ Yu 1986, p. 456.

- ^ Watson 1993, p. 222.

- ^ 薛瑜婷 (2018-09-19). "閩越重要人物——無諸與餘善". Academy of Chinese Studies (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 2024-05-21. Retrieved 2025-09-13.

- ^ Watson 1993, p. 224.

- ^ Amies & Ban 2020, pp. 41–45.

- ^ Chen, Jonas Chung-yu (24 January 2008). "[ARCHAEOLOGY IN CHINA AND TAIWAN] Sea nomads in prehistory on the southeast coast of China". Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association. 22. doi:10.7152/bippa.v22i0.11805 (inactive 2025-07-12).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ Goodenough, Ward H. (1996). Prehistoric Settlement of the Pacific. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. p. 43. ISBN 087169865X. OL 1021882M.

Further reading

[edit]- Amies, Alex; Ban, Gu (2020). Hanshu Volume 95 The Southwest Peoples, Two Yues, and Chaoxian: Translation with Commentary. Gutenberg Self Publishing Portal. ISBN 978-0-9833348-7-3.

- Taylor, Jay (1983), The Birth of the Vietnamese, University of California Press

- Watson, Burton (1993), Records of the Grand Historian by Sima Qian: Han Dynasty II Revised Edition, Columbia University Press

- Whiting, Marvin C. (2002), Imperial Chinese Military History, Writers Club Press

- Wylie, A. (1880). "History of the South-Western Barbarians and Chaou-Seen. Translated from the "Tseen Han Shoo," Book 95". The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 9: 78. doi:10.2307/2841871. JSTOR 2841871. OCLC 5545526568.

- Yu, Yingshi (1986). Twitchett, Denis; Loewe, Michael (eds.). Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220. University of Cambridge Press. ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

External links

[edit]- History of Minyue I (Chinese)

- History of Minyue II (Chinese)