Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

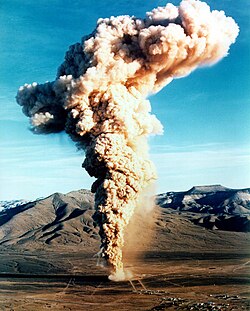

Yucca Flat

View on Wikipedia

Yucca Flat is a closed desert drainage basin, one of four major nuclear test regions within the Nevada Test Site (NTS), and is divided into nine test sections: Areas 1 through 4 and 6 through 10. Yucca Flat is located at the eastern edge of NTS, about ten miles (16 km) north of Frenchman Flat, and 65 miles (105 km) from Las Vegas, Nevada.[2] Yucca Flat was the site for 739 nuclear tests – nearly four of every five tests carried out at the NTS.[3]

Yucca Flat has been called "the most irradiated, nuclear-blasted spot on the face of the earth".[2] In March 2009, TIME identified the 1970 Yucca Flat Baneberry Test, where 86 workers were exposed to radiation, as one of the world's worst nuclear disasters.[4]

Geology

[edit]

The open, sandy geology of Yucca Flat in the Tonopah Basin made for straightforward visual documentation of atmospheric nuclear tests. When testing went underground, deep layers of sedimentary soil from the erosion of the surrounding mountains allowed for relatively easy drilling of test holes.[5]

Hundreds of subsidence craters dot the desert floor. A crater could develop when an underground nuclear explosion vaporized surrounding bedrock and sediment. The vapor cooled to liquid lava and pooled at the bottom of the cavity created by the explosion. Cracked rock and sediment layers above the explosion often settled into the cavity to form a crater.

At the south end of Yucca Flat is Yucca Lake, also called Yucca Dry Lake. The dry, alkaline lake bed holds a restricted runway (Yucca Airstrip) which was built by the Army Corps of Engineers before nuclear testing began in the area. To the west of the dry lake bed is News Nob, a rocky outcropping from which journalists and VIPs were able to watch atmospheric nuclear tests at Yucca Flat.[5]

Nearby

[edit]West of the dry lake bed, cresting the top of Yucca Pass, is Control Point, or CP-1, the 31,600 sq ft (2,940 m2) complex of buildings that contains testing and monitoring equipment for nuclear tests, and a cafeteria that seats 32. CP-1 overlooks Yucca and Frenchman Flats. Today, Control Point is the center for support of all activity at the NTS.[5]

A subsidence crater in nearby Area 5 is used to store containers of contaminated scrap metal and debris; its radioactivity is periodically measured.

Nuclear testing

[edit]Yucca Flat saw 739 nuclear tests, including 827 separate detonations. The higher number of detonations is from single tests that included multiple nuclear explosions occurring within a 0.1-second time window and inside a 1.2 mi (2 km) diameter circle. Sixty-two such tests took place at NTS.[3]

No test at Yucca Flat ever exceeded 500 kilotons of expected yield. Tests of larger explosions were carried out at Rainier Mesa and Pahute Mesa, as their geology allowed deeper test shafts.

First tests

[edit]

The first test explosion at Yucca Flat came after five atmospheric tests at nearby Area 5 as part of Operation Ranger. On October 22, 1951, the "Able" test of Operation Buster was detonated at the top of a tower in Area 7, resulting in a nuclear yield less than an equivalent kilogram of TNT; the shot was a fizzle. It was the world's first failure of a nuclear device. Over the next two weeks, four successful tests were conducted by bomber aircraft that dropped nuclear weapons over Area 7.

The first underground test at NTS was the "Uncle" shot of Operation Jangle. Uncle detonated on November 29, 1951, within a shaft sunk into Area 10.

Operation Plumbbob

[edit]In Area 9, the 74-kiloton "Hood" test on July 5, 1957, part of Operation Plumbbob, was the largest atmospheric test ever conducted within the continental United States;[6] nearly five times as large in yield as the bomb dropped on Hiroshima. A balloon carried Hood up to 1,510 ft (460 m) above the ground where it was detonated. Over 2,000 troops took part in the test in order to train them in conducting operations on the nuclear battlefield. The test released 11 megacuries (410 PBq) of iodine-131 (131I) into the air.[7] With a relatively brief half-life of eight days, 131I is useful as a determinant in tracking specific nuclear contamination events. Iodine-131 comprises about 2% of radioactive materials in a cloud of dust stemming from a nuclear test, and causes thyroid problems if ingested.[7]

The "John" shot of Plumbbob, on July 19, 1957, was the first test firing of the nuclear-tipped AIR-2 Genie air-to-air rocket designed to destroy incoming enemy bombers with a nuclear explosion. The two-kiloton warhead exploded approximately three miles (4.8 km) above five volunteers and a photographer who stood unprotected at "ground zero" in Area 10 to demonstrate the purported safety of battlefield nuclear weapons to personnel on the ground.[8] The test also demonstrated the ability of a fighter aircraft to deliver a nuclear-tipped rocket and avoid being destroyed in the process. A Northrop F-89J fired the rocket.

Project Plowshare

[edit]

A dramatically different test shot was the "Sedan" test of Operation Storax on July 6, 1962, a 104 kiloton shot for Project Plowshare which sought to discover whether nuclear weapons could be used for peaceful means in creating lakes, bays or canals. The explosion displaced twelve million tons of earth, creating a crater 1,280 ft (390 m) wide and 320 ft (98 m) deep in Area 10. For an underground shot, a relatively large amount of energy was vented to the atmosphere, estimated to be 2.5 kilotons (7.4 bars of pressure).[9] Two radioactive dust clouds rose up from the explosion and traveled across the United States, one at 10,000 ft (3,000 m) and the other at 16,000 ft (4,900 m). Both dropped radioactive particles across the USA before crossing into the sky above the Atlantic Ocean. Among many other radioisotopes, the clouds carried 880 kCi (33 PBq) of 131I.

Sedan Crater was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1994.[10]

Baneberry

[edit]

Area 8 hosted the "Baneberry" shot of Operation Emery on December 18, 1970. The Baneberry 10-kiloton test detonated 900 ft (270 m) below the surface but its energy cracked the soil in unexpected ways, causing a fissure near ground zero and the failure of the shaft and cap.[11] A plume of fire and dust was released 3.5 minutes after initiation,[12] raining fallout on workers in different locations within NTS. The radioactive plume released 6.7 megacuries (250 PBq) of radioactive material, including 80 kCi (3.0 PBq) of iodine-131.[7][13] After dropping a portion of its material locally, the plume's lighter particles were carried to three altitudes and conveyed by winter storms and the jet stream to be deposited heavily as radionuclide-laden snow in Lassen and Sierra counties in northeast California, and to lesser degrees in southern Idaho, northern Nevada and some eastern sections of Oregon and Washington states.[14] The three diverging jet stream layers conducted radionuclides across the US to Canada, the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean.

Some 86 workers at the site were exposed to radioactivity, but according to the Department of Energy none received a dose exceeding site guidelines and, similarly, radiation drifting offsite was not considered to pose a hazard by the DOE.[15] In March 2009, TIME magazine identified the Baneberry Test as one of the world's worst nuclear disasters.[4]

Two US Federal court cases resulted from the Baneberry event. Two NTS workers who were exposed to high levels of radiation from Baneberry died in 1974, both from acute myeloid leukemia. The district court found that although the Government had acted negligently, the radiation from the Baneberry test did not cause the leukemia cases. The district decision was upheld on appeal in 1996.[16][17]

Huron King

[edit]

As part of Operation Tinderbox, on June 24, 1980, a small satellite prototype (DSCS III) was subjected to radioactivity from the "Huron King" shot in a vertical line-of-sight (VLOS) test undertaken in Area 3. This was a program to improve the database on nuclear hardening design techniques for defense satellites. The VLOS test configuration involved placing a nuclear device (less than 20 kilotons) at the bottom of a shaft. A communications satellite or other experiment was placed in a partially evacuated test chamber simulating a space environment. The test chamber was parked at ground level at the top of the shaft. At zero time, the radiation from the device shot up the vertical pipe to the surface test chamber. Mechanical closures then intercepted and sealed the pipe, preventing the explosive shock wave from damaging the targets. The test chamber was immediately disconnected by remote control from the pipe and quickly winched to safety before the ground could subside to form a crater. The Huron King test cost US$10.3 million in 1980 (equivalent to $39.3 million today).[18]

Last test

[edit]The final test at Yucca Flat (also the last test at the entire Nevada Test Site) was Operation Julin's "Divider" on September 23, 1992, just prior to the moratorium temporarily ending all nuclear testing. Divider was a safety experiment test shot that was detonated at the bottom of a shaft sunk into Area 3.

Abandoned tests

[edit]

Three tests planned for 1993 have been abandoned in place, two in Yucca Flat. The Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty had been strongly supported by the UN General Assembly in 1991, and negotiations began in earnest in 1993. The United States, on October 3, 1992, suspended all nuclear weapons testing programs in anticipation of eventual ratification of the treaty. The partially assembled cabling, towers and equipment for shot "Icecap" in Area 1 and shot "Gabbs" in Area 2 lie amid weeds and blowing dust, waiting for a possible resumption of nuclear testing. Shot "Greenwater" awaits its fate in Area 19 at Pahute Mesa. "Icecap" was to be a joint US-UK test event.[19]

Radioactivity

[edit]UGTA

[edit]The United States Department of Energy produced a report in April, 1997, on a subproject of the Nevada Environmental Restoration Project. The larger project involves environmental restoration and mitigation activities in the NTS, Tonopah Test Range, Nellis Air Force Range, and eight further sites in five other states. The Underground Test Area (UGTA) subproject focuses on defining the boundaries of areas containing unsafe water contaminated with radionuclides from underground nuclear tests. The ongoing subproject is tasked with predicting the future extent of contaminated water due to natural flow and it is expected to quantify safe limits for human health. Yucca Flat was identified as a Corrective Action Unit (CAU).[20][21] Because of the great expense and virtual impossibility of cleaning up the Nevada Test Site, it has been characterized as a "national sacrifice zone."[22]

USGS

[edit]In 2003, the United States Geological Survey (USGS) collected and processed magnetotellurics (MT) and audio-magnetotelluric (AMT) data at the Nevada Test Site from 51 data stations placed in and near Yucca Flat to get a more accurate idea of the pre-Tertiary geology found in the Yucca Flat Corrective Action Unit (CAU). The intent was to discover the character, thickness, and lateral extent of pre-Tertiary rock formations that affect the flow of underground water. In particular, a major goal was to define the upper clastic confining unit (UCCU) in the Yucca Flat area.[23][24]

First responder training

[edit]

The radioactivity present on the ground in Area 1 provides a radiologically contaminated environment for the training of first responders.[25] Trainees are exposed to methods of radiation detection and its health hazards. Further training takes place in other areas of NTS.[26]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ United States Geological Survey. Nevada Test Site. Geologic Surface Effects of Underground Nuclear Testing. Accessed on April 18, 2009.

- ^ a b Gerald H. Clarfield and William M. Wiecek (1984). Nuclear America: Military and Civilian Nuclear Power in the United States 1940–1980, Harper & Row, New York, p. 202.

- ^ a b "US Department of Energy. Nevada Operations Office. United States Nuclear Tests: July 1945 through September 1992 (December 2000)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-05. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- ^ a b The Worst Nuclear Disasters

- ^ a b c "Online Nevada. Alan Moore. Yucca Flat (Last Updated: 2007-04-19 09:22:27)". Archived from the original on 2012-02-14. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- ^ "Operation Plumbbob". 2003-07-12. Retrieved 2010-04-24.

- ^ a b c "National Cancer Institute. National Institute of Health. History of the Nevada Test Site and Nuclear Testing Background" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-12-21. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- ^ "California Literary Review. Peter Kuran. Images from How To Photograph an Atomic Bomb. (October 22, 2007)". Archived from the original on May 24, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2008.

- ^ Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. J. B. Knox. A Heuristic Examination of Scaling. (July 14, 1969)

- ^ National Register of Historic Places. Nye County, Nevada.

- ^ "Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. News Archive. Tarabay H. Antoun. Three Dimensional Simulation of the Baneberry Nuclear Event" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-05-27. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- ^ "University of Las Vegas. Nevada Test Site Oral History Project. Clifford Olsen (interviewed September 20, 2004)". Archived from the original on August 1, 2008. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ "Shundahai Network. Area 8". Archived from the original on 2008-07-23. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- ^ Two-Sixty Press. Richard L. Miller. Fallout Maps. Gallery 33

- ^ "Nuclear testing at the Nevada Test Site". Brookings.

- ^ "United States Court of Appeals, Ninth Circuit. James Randall Roberts v. United States of America. (1996)". Archived from the original on 2008-07-16. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- ^ "University of Nevada, Las Vegas. Libraries Special Collections. MS 19. Baneberry Collection: Court proceedings of William Nunamaker vs. the United States and Harley Roberts vs. the United States, as they came to trial January 1979, in Federal District Court, Las Vegas. Donated by Judge Robert Foley". Archived from the original on 2008-05-12. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- ^ Nuclear weapon archive. Underground Testing at the Nevada Test Site

- ^ "US Department of Energy. Nevada Operations Office. Library. Factsheets. Icecap (May 2007)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-27. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- ^ DOE Nevada Operations Office, Las Vegas, Nevada. Underground test area quality assurance project plan, Nevada test site, Nevada. Revision 1 (April 1997)

- ^ DOE Scientific and Technical Information. Information Bridge. Bibliographic Citation. doi:10.2172/471470

- ^ Webster, Donovan (1998-05-12). Aftermath: The Remnants of War: From Landmines to Chemical Warfare – The Devastating Effects of Modern Combat. Vintage. ISBN 0-679-75153-X.

- ^ USGS. Science topics. Magnetotelluric Data, North Central Yucca Flat, Nevada Test Site, Nevada. Jackie M. Williams, Brian D. Rodriguez, and Theodore H. Asch. (November 2005)

- ^ USGS Deep Resistivity Structure of Yucca Flat, Nevada Test Site, Nevada. Theodore H. Asch, Brian D. Rodriguez, Jay A. Sampson, Erin L. Wallin, and Jackie M. Williams. (September 2006)

- ^ "US Department of Energy. Nevada Operations Office. Library. Photo Library. Photo Details T1area_CTOS". Archived from the original on 2008-08-04. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- ^ "First Responder Training". U.S. Department of Energy. Archived from the original on 2008-05-02. Retrieved 2010-07-19.

External links

[edit]- Yucca Flat Archived 2012-02-14 at the Wayback Machine at the Online Nevada Encyclopedia. Includes photo gallery.

Yucca Flat

View on GrokipediaYucca Flat is a dry lake basin and closed topographic depression spanning approximately 10 by 20 miles within the Nevada National Security Site in Nye County, Nevada, about 65 miles northwest of Las Vegas.[1] It functioned as the principal location for U.S. nuclear weapons testing on continental soil, accommodating 659 underground nuclear detonations between 1951 and 1992, along with numerous atmospheric tests prior to the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty.[2] These activities, conducted to develop and refine the nation's nuclear arsenal amid Cold War tensions, resulted in over 700 total explosions in the basin, producing distinctive subsidence craters that render the area one of the most pockmarked terrains globally.[3][4] The basin's alluvial geology and relative isolation facilitated safe containment of underground blasts, with most devices emplaced in vertical shafts penetrating saturated volcanic tuffs and older carbonate rocks.[2] Notable operations included the 104-kiloton Sedan test in 1962, part of the Plowshare Program for peaceful nuclear excavation, which excavated a 320-foot-deep crater measuring 1,280 feet across—the largest human-made crater from a single explosion.[5] Yucca Flat's testing legacy underpinned advancements in warhead design, yield prediction, and stockpile stewardship, while post-testing remediation efforts addressed groundwater contamination, achieving closure for the Yucca Flat corrective action unit by 2020.[6] Today, the site supports non-proliferation training, environmental monitoring, and serves as a testament to the empirical validation of nuclear physics principles through iterative experimentation.[5]

Geography and Geology

Location and Topography

Yucca Flat constitutes a topographic and structural basin situated in the northeastern sector of the Nevada National Security Site, Nye County, Nevada, United States.[7] Centered at coordinates 37.0534°N, 116.0540°W, it forms part of the Basin and Range physiographic province, approximately 105 km northwest of Las Vegas.[8] The basin spans roughly 200 square miles (518 km²), encompassing nuclear test areas 1 through 4, 6, and 7 of the former Nevada Test Site. Its valley floor, filled with Quaternary alluvium, exhibits low relief with an average elevation of 4,062 feet (1,238 m).[8] A seasonally dry playa occupies the southern end, while surrounding low-elevation mountain ranges, composed primarily of Tertiary volcanic rocks, bound the flat to the north, east, and west.[7] These topographic features—a broad, arid expanse with closed drainage—facilitated its selection for nuclear testing due to the unobstructed visibility and containment potential of surface effects.[9]Geological Composition and Features

Yucca Flat constitutes a structural and topographic basin within the Basin and Range province, featuring low-relief terrain with a central playa at its southern extremity. The basin fill primarily comprises Quaternary alluvial deposits, which overlie a thick sequence of Tertiary volcanic rocks and are underlain by Paleozoic sedimentary formations. These alluvial sediments exhibit hydraulic heterogeneity, subdivided into an older, volcanic-rich basal tuffaceous alluvium and a younger overlying mixed alluvium derived from diverse surrounding sources.[10][11] The volcanic foundation consists mainly of Miocene-age tuffs and flows associated with the Timber Mountain caldera complex, forming part of the regional volcanic stratigraphy that includes units from the Paintbrush and Timber Mountain groups. These volcanics, reaching thicknesses up to several kilometers, exhibit varying degrees of welding and alteration, influencing subsurface hydrology and structural integrity. Beneath the volcanics lie Paleozoic carbonate rocks, such as limestones and dolomites, interspersed with older clastic sediments, resting on a pre-Tertiary crystalline basement of granitic composition.[12][13][14] Structurally, Yucca Flat formed through Miocene-to-Quaternary extensional tectonics, involving block faulting and basin subsidence that displaced geologic units along normal faults bounding the basin margins. This faulting, accompanied by tilting of volcanic layers, created a half-graben configuration with displacements exceeding hundreds of meters in places. The basin's evolution reflects post-middle Miocene downwarping, accommodating sediment accumulation while preserving stratigraphic relations discernible from borehole data across the region.[15][16][17]Nuclear Weapons Testing History

Establishment and Atmospheric Era (1951-1963)

The Nevada Test Site (NTS), encompassing Yucca Flat, was designated by President Harry S. Truman on December 18, 1950, for continental nuclear testing following initial Pacific proving grounds. Initial detonations commenced on January 27, 1951, with Operation Ranger's Able shot at Frenchman Flat, south of Yucca Flat, using a 1-kiloton device air-dropped from a B-50 bomber. Yucca Flat, a 28-by-16-mile intermontane basin filled with Quaternary alluvium over Tertiary volcanic tuffs, was selected for expansion due to its isolation, providing greater standoff distances for instrumentation and troop maneuvers compared to Frenchman Flat's closer proximity to populated areas.[18][19][1] Yucca Flat's first nuclear tests occurred during Operation Buster–Jangle from October 22 to November 29, 1951, shifting some activities northward for enhanced safety after fallout concerns from earlier Frenchman Flat shots. Key atmospheric events included Shot Charlie, a 14-kiloton airdrop on October 30 over Area 9, and Shot Dog, a 21-kiloton airdrop on November 1 over Area 7 at 1,417 feet altitude, both evaluating weapons effects on ground forces from Camp Desert Rock. These tests, involving over 7,000 troops, yielded data on blast overpressure, thermal radiation, and cratering, with yields from 0.2 to 31 kilotons across the series' eight detonations, six atmospheric.[20][19] From 1952 to 1963, Yucca Flat hosted dozens of atmospheric tests across operations like Tumbler–Snapper (eight airdrops and towers, yields up to 31 kilotons), Upshot–Knothole (11 shots, including the 61-kiloton Grable artillery-fired device), and Teapot (14 shots, advancing thermonuclear designs with yields to 43 kilotons), primarily via airdrops over Areas 1–10 to simulate tactical delivery. These detonations, totaling part of NTS's 100 atmospheric tests with combined yields exceeding 500 megatons equivalent, prioritized yield calibration, fission-fusion staging, and survivability assessments amid escalating Cold War imperatives. Fallout from unsterilized shots dispersed radionuclides like iodine-131 and cesium-137, prompting health monitoring by the Atomic Energy Commission, though containment failures highlighted risks over Nevada and Utah.[19][21] The era concluded with the Limited Test Ban Treaty on August 5, 1963, prohibiting atmospheric, underwater, and space tests, transitioning Yucca Flat to underground operations while underscoring its role in stockpiling over 200 designs through empirical validation rather than simulation alone.[19]Underground Testing Period (1963-1992)

Following the signing of the Limited Test Ban Treaty on August 5, 1963, which barred nuclear explosions in the atmosphere, underwater, and outer space, the United States shifted all nuclear testing at the Nevada Test Site to underground configurations, with Yucca Flat serving as the primary location for such activities until the 1992 testing moratorium.[22] This transition aimed to contain radioactive fallout while continuing weapons development, effects evaluation, and stockpile certification. Over the period from 1963 to 1992, Yucca Flat hosted the majority of the Nevada Test Site's approximately 800 underground tests, with shaft emplacements accounting for over 90 percent of all underground detonations nationwide.[23][24] Underground tests in Yucca Flat predominantly utilized vertical shaft drilling, involving boreholes 3 to 12 feet in diameter and depths ranging from 600 to 2,200 feet, into which nuclear devices were lowered and detonated.[24][5] Containment was achieved by backfilling or "stemming" the shaft above the device with layered materials such as sand, gravel, and epoxy plugs to trap radionuclides within the resulting molten rock cavity formed by the explosion.[23] Tunnel tests, conducted in horizontal drifts for specific weapon effects assessments, were less common but complemented shaft testing in areas like Rainier Mesa adjacent to Yucca Flat. Yields varied from sub-kiloton to hundreds of kilotons, with early post-treaty events like Bilby on September 13, 1963 (249 kilotons), demonstrating containment in volcanic tuff while producing a subsidence crater 1,800 feet wide and 80 feet deep.[5] Between 1951 and 1992, Yucca Flat accommodated 658 underground nuclear tests encompassing 747 individual detonations, the vast majority occurring after 1963 as atmospheric testing ceased. These efforts supported iterative improvements in nuclear warhead designs, safety features, and performance under diverse geological conditions, including alluvial fill and fractured tuff. Drilling operations alone spanned 1.5 million feet of borehole (equivalent to 280 miles) from 1961 to 1992, often requiring up to 60 days per 1,000-foot section due to challenging porous terrain.[5] Successful containment minimized surface release in most cases, though subsidence craters—resulting from cavity roof collapse—became characteristic surface features, their sizes determined by yield, depth, and lithology.[23] The final underground test at the site, Divider on September 23, 1992 (yield under 20 kilotons), marked the end of this era amid international pressure for a comprehensive test ban.[5]Peaceful Nuclear Applications

Yucca Flat hosted experiments under Project Plowshare, a U.S. Atomic Energy Commission initiative launched in 1957 to explore non-military applications of nuclear explosions, such as large-scale excavation for civil engineering projects including canals, harbors, and mining.[25] These efforts aimed to leverage the immense energy release from nuclear detonations to move vast quantities of earth more efficiently than conventional methods.[26] The most prominent Plowshare test in Yucca Flat was the Sedan detonation on July 6, 1962, conducted in Area 10 as part of Operation Storax.[27] This shallow underground explosion involved a 104-kiloton thermonuclear device buried 194 meters deep, designed to simulate excavation potential by creating a large crater.[26] The blast displaced approximately 12 million tons of earth, forming a crater initially 390 meters in diameter and 100 meters deep, demonstrating the capability to excavate volumes equivalent to millions of cubic yards in seconds.[27] Proponents envisioned applications like deepening ports or constructing a sea-level canal across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec as alternatives to the Panama Canal.[25] Despite technical success in earth-moving, the Sedan test released significant radioactive fallout, contributing about 7% to the total radionuclides from all U.S. nuclear tests due to the shallow burial and vaporization of surface materials.[27] This unexpected dispersion, lofted 3.7 kilometers high and carried by winds, underscored challenges in containing radioactivity for civilian uses, leading to heightened scrutiny and eventual constraints under the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty.[26] Plowshare's excavation experiments at the Nevada Test Site, including those in Yucca Flat, ultimately highlighted practical limitations, with no large-scale peaceful applications realized due to environmental, political, and economic factors.[25]Notable Tests and Incidents

Operation Plumbbob

Operation Plumbbob was a series of 29 nuclear tests conducted by the United States at the Nevada Test Site from May 28 to October 7, 1957, including 24 detonations with nuclear yields and five safety experiments designed to assess accidental detonation risks.[28][29] The operation aimed to refine thermonuclear weapon designs, evaluate military effects on equipment and personnel, and verify safety mechanisms to prevent nuclear yield from high-explosive failures in weapons.[28] Multiple tests occurred in Yucca Flat, the primary basin for tower, balloon, and shaft detonations during this era, contributing to its role as the epicenter of over 700 subsequent underground tests.[30] Yields ranged from sub-kiloton levels in safety shots to a maximum of 74 kilotons in the Hood test, with atmospheric releases generating localized fallout monitored by the Atomic Energy Commission.[28][31] The tests encompassed diverse configurations: tower shots for ground-burst simulations, balloon-suspended devices for air-burst effects, and underground shafts for containment trials, alongside the first evaluations of "one-point safety" where devices were subjected to single high-explosive lens detonations without nuclear chain reaction.[32] In Yucca Flat's Areas 7, 9, and 10, at least 15 detonations took place, including full-scale proofs of boosted fission and thermonuclear primaries, with data used to enhance warhead reliability for intercontinental ballistic missiles.[31] Military participation involved over 14,000 Department of Defense personnel, including troop maneuvers to study blast and radiation impacts, such as 2,100 Marines positioned 5,500 yards from the Hood shot for simulated combat exposure.[28] Safety experiments, like the Pascal series, tested arming and firing systems under mishandling scenarios, confirming no unintended yields despite some high-explosive anomalies.[32] Notable Yucca Flat tests included Hood on July 5, 1957—a 74-kiloton tower detonation in Area 9, the highest-yield atmospheric event at the site, which propelled a steel plate to estimated escape velocity during analysis.[28][31] Smoky, detonated August 31 in Area 8 at 44 kilotons via balloon, exposed 1,150 troops to fallout for dosimetry studies, yielding data on personnel vulnerability but prompting later health reassessments due to elevated cancer risks among participants.[28][33] Incidents during safety shots, such as the accidental drop of the Pascal-B device on July 26, highlighted handling risks but resulted in no nuclear release, reinforcing procedural safeguards.[31] Overall, Plumbbob advanced U.S. nuclear capabilities amid Cold War pressures, though retrospective analyses from Defense Threat Reduction Agency reports note incomplete initial containment and monitoring of radionuclides in Yucca Flat's alluvial basins.[28]| Test Name | Date | Yield (kt) | Type/Location | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hood | July 5, 1957 | 74 | Tower, Yucca Flat Area 9 | Largest atmospheric yield at NTS; military effects testing.[28][31] |

| Smoky | August 31, 1957 | 44 | Balloon, Yucca Flat Area 8 | Troop exposure; significant fallout.[28][31] |

| Galileo | September 2, 1957 | 11 | Tower, Yucca Flat | Weapon proof test.[31] |