Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

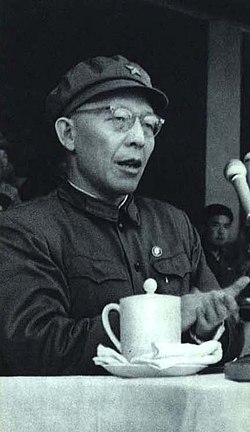

Zhang Chunqiao

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2023) |

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Chinese. (March 2023) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Key Information

| Zhang Chunqiao | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 张春桥 | ||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 張春橋 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Maoism |

|---|

|

Zhang Chunqiao (Chinese: 张春桥; 1 February 1917 – 21 April 2005; also spelled as Chang Chun-chiao[1]) was a Chinese political theorist, writer, and politician. He came to the national spotlight during the late stages of the Cultural Revolution, and was a member of the ultra-Maoist group dubbed the "Gang of Four".

Zhang joined the Chinese Communist Party in 1938, later becoming a prominent journalist in charge of Jiefang Daily after the establishment of the People's Republic. He rose to prominence after his October 1958 article entitled "Destroy the Ideology of Bourgeois Right" caught the attention of Mao Zedong, who ordered its reproduction in People's Daily.

With the onset of the Cultural Revolution, he was appointed as a member of the Cultural Revolution Group. In 1967, Zhang organized the Shanghai People's Commune and briefly became its chairman, effectively overthrowing the local Shanghai government and local party structures. Afterwards, he was appointed as the director of the Shanghai Revolutionary Committee. He joined the Politburo in 1969, and its inner Standing Committee in 1973, reaching his zenith as the country's second-ranking vice premier in 1975.

After Mao's death in 1976, Zhang was arrested along with the other members of what would become known as the Gang of Four. He was sentenced to death with a two-year reprieve, later commuted to life imprisonment, and then further reduced to 18 years. He was released from prison in 1998 to undergo medical treatment, and died in 2005.

Early life

[edit]Born in Juye County, Shandong, Zhang worked as a writer in Shanghai in the 1930s, developing strong connections within the city. After attending a 1938 conference in Yan'an, he joined the Chinese Communist Party.

Zhang first saw Mao Zedong at a party in 1938, and spoke to him for the first time in 1939, while he was serving as "head of the propaganda section of a public school in northern Shaanxi."[2]

People's Republic of China

[edit]With the proclamation of the People's Republic of China, Zhang became a prominent Shanghai journalist, put in charge of the newspaper Jiefang Daily. Here, he met Jiang Qing.

Zhang first came to prominence as the result of his October 1958 article in Jiefang Daily entitled "Destroy the Ideology of Bourgeois Right". Mao Zedong took notice of the article, and ordered it to be reprinted in People's Daily, along with an accompanying "Editor's Note" expressing his mild approval.[3] In the article, Zhang praised the Red Army's egalitarian focus in the 1930s, including its communist mutual relations not just internally but with the masses.[4]: 128 According to Zhang, "When comrades lived used to live under the supply system they did not envy wage labor, and people liked this kind of expression of a living institution of relations of equality. Before long, however, this kind of system was attacked by the ideology of bourgeois right. The core of the ideology of the bourgeois right is the wage system."[4]: 129

Zhang was seen as one of Mao's firmest supporters as the chairman engaged in an ideological struggle within party leadership with rival revolutionary Liu Shaoqi.

Cultural Revolution

[edit]Zhang spent much of the Cultural Revolution shuttling between Beijing and Shanghai. He arrived in Shanghai in November 1966 at representing the Cultural Revolution Group in their push to stop Cao Diqiu from dispersing workers in Anting. He signed the "Five-Point Petition of Workers", and in February 1967 organized the Shanghai People's Commune with Wang Hongwen and Yao Wenyuan, essentially overthrowing the city government and local party structure, becoming chairman of the city's Revolutionary Committee, a title that essentially combined the former posts of mayor and party secretary. This structure would persist until the latter post was restored in 1971.[citation needed]

In April 1969, he joined the Politburo, and in 1973 he was promoted to the Standing Committee therein. In January 1975, Zhang became the second-ranked Vice Premier, and penned "On Exercising All-Round Dictatorship Over the Bourgeoisie" to promote the theoretical study of the dictatorship of the proletariat. Deng Xiaoping was the first-ranked Vice Premier at the time, but was out of the office by 1976. After the death of Zhou Enlai in January 1976, Zhang Chunqiao competed for the position of Premier with his political opponent Deng Xiaoping. However, Mao did not choose either of them. Instead, he chose Hua Guofeng as the new Premier.

Arrest and death

[edit]Zhang was arrested along with the other members of the so-called "Gang of Four" in October 1976, as part of a conspiracy by Ye Jianying, Li Xiannian and the new party leader Hua Guofeng. He was expelled from the Communist Party in July 1977, and then sentenced to death with a two-year reprieve in 1984, alongside Jiang Qing. His sentence was later commuted to life imprisonment, and was further reduced to 18 years in December 1997.

Zhang remained silent during his 1980 trial, and refused to speak until his relatives were allowed to visit him in prison years later; according to his daughter, Weiwei, he could barely talk by that time.[2] He remained critical of the Communist Party under Deng Xiaoping and his successors in letters to his daughter, and stayed true to his Maoist beliefs, predicting the 21st century would see the triumph of socialist revolution in several countries.[2]

In 1998, Zhang was released from prison to undergo medical treatment, then lived in obscurity in Shanghai[citation needed] until he died from pancreatic cancer in April 2005.[5]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Zhang was briefly the head of the Shanghai People's Commune in February 1967.

References

[edit]- ^ Wade, Nigel. "MAO's Widow Arrested." Daily Telegraph, 12 Oct. 1976, pp. [1]+. The Telegraph Historical Archive. Accessed 21 June 2025.

- ^ a b c Zhang Chunqiao (2025). Excerpts from Zhang Chunqiao’s Home Letters from Prison. Chunqiao Publications.[dead link]

- ^ Chang, Parris H. (1978). Power and Policy in China (2nd ed.). University Park, Pa.: Penn State University Press. p. 100, and n21–22. ISBN 978-0-271-00544-7.

- ^ a b Kindler, Benjamin (2025). Writing to the Rhythm of Labor: Cultural Politics of the Chinese Revolution, 1942–1976. New York City, NY: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-21932-7.

- ^ "China's Gang of Four member dies". 10 May 2005.