Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Zwickau

View on Wikipedia

Zwickau (German pronunciation: [ˈtsvɪkaʊ] ⓘ; Upper Sorbian: Šwikawa) is the fourth-largest city of Saxony, Germany, after Leipzig, Dresden and Chemnitz, with around 88,000 inhabitants,.

Key Information

The West Saxon city is situated in the valley of the Zwickau Mulde (German: Zwickauer Mulde; progression: Mulde→ Elbe→ North Sea), and lies in a string of cities sitting in the densely populated foreland of the Elster and Ore Mountains stretching from Plauen in the southwest via Zwickau, Chemnitz and Freiberg to Dresden in the northeast. Zwickau is the seat of the Zwickau District, the most densely populated district in the new states of Germany.

Zwickau is the seat of the West Saxon University of Zwickau (German: Westsächsische Hochschule Zwickau) with campuses in Zwickau, Markneukirchen, Reichenbach im Vogtland and Schneeberg (Erzgebirge). The city is the birthplace of composer Robert Schumann.

Zwickau has historically been one of the centres of the German automotive industry.[3][4] It is the cradle of Audi and its forerunner Horch. Horchwerke AG Zwickau was founded there in 1904 and was renamed to Audiwerke Zwickau AG in 1909. Zwickau was also the seat of VEB Sachsenring (now Sachsenring GmbH), which produced East Germany's most popular car, the Trabant, in Zwickau. Since 1990, there is a large Volkswagen plant in Zwickau-Mosel.

The 167-kilometre-long (104-mile) Zwickau Mulde River, originating in Schöneck/Vogtl. in the Western Ore Mountains, traverses the city in a south-to-north direction. It enters Zwickau between Zwickau-Cainsdorf and Zwickau-Bockwa, and leaves at Zwickau-Schlunzig near the Volkswagen plant, and is spanned by 17 bridges within the city. The Silver Road, Saxony's longest tourist route, connects Dresden with Zwickau.[5]

Zwickau can be reached by car via the nearby Autobahns A4 and A72, the main railway station (Zwickau Hauptbahnhof), via a public airfield which takes light aircraft, and by bike along the Zwickau Mulde River on the so-called Mulderadweg.[6]

History

[edit]

The region around Zwickau was settled by Sorbs as early as the 7th century AD. The name Zwickau is probably a Germanization of the Sorbian toponym Šwikawa, which derives from Svarozič, the Slavic Sun and fire god.[7] In the 10th century, German settlers began arriving and the native Slavs were Germanized. A trading place known as terretorio Zcwickaw (in Medieval Latin) was mentioned in 1118. The settlement received a town charter in 1212, and hosted Franciscans and Cistercians during the 13th century. Zwickau was a free imperial city from 1290 to 1323, but was subsequently granted to the Margraviate of Meissen. Although regional mining began in 1316, extensive mining increased with the discovery of silver in the Schneeberg in 1470. Because of the silver ore deposits in the Erzgebirge, Zwickau developed in the 15th and 16th centuries and grew to be an important economic and cultural centre of Saxony.

Its nine churches include the Gothic church of St. Mary (1451–1536), with a spire 285 ft (87 m) high and a bell weighing 51 tons. The church contains an altar with wood carvings, eight paintings by Michael Wohlgemuth and a pietà in carved and painted wood by Peter Breuer.

The late Gothic church of St. Catharine has an altar piece ascribed to Lucas Cranach the elder, and is remembered because Thomas Müntzer was once pastor there (1520–22). The city hall was begun in 1404 and rebuilt many times since. The municipal archives include documents dating back to the 13th century.

Early printed books from the Middle Ages, historical documents, letters and books are kept in the City Archives (e.g. Meister Singer volumes by Hans Sachs (1494–1576)), and in the School Library founded by scholars and by the city clerk Stephan Roth during the Reformation.

In 1520 Martin Luther dedicated his treatise "On the Freedom of the Christian Man" to his friend Hermann Muehlpfort, the Lord Mayor of Zwickau. The Anabaptist movement of 1525 began at Zwickau under the inspiration of the "Zwickau prophets".[8] After Wittenberg, it became the first city in Europe to join the Lutheran Reformation. The late Gothic Gewandhaus (cloth merchants' hall), was built in 1522–24 and is now converted into a theatre. The city was seriously damaged during the Thirty Years' War.[citation needed]

The old city of Zwickau, perched on a hill, is surrounded by heights with extensive forests and a municipal park. Near the city are the Hartenstein area, for example, with Stein and Wolfsbrunn castles and the Prinzenhöhle cave, as well as the Auersberg peak (1019 meters) and the winter sports areas around Johanngeorgenstadt and the Vogtland.

In the Old Town the Cathedral and the Gewandhaus (cloth merchants' hall) originate in the 16th century and when Schneeberg silver was traded. In the 19th century the city's economy was driven by industrial coal mining and later by automobile manufacturing.

During World War II, in 1942, a Nazi show trial of the members of the Czarny Legion Polish underground resistance organization from Gostyń was held in Zwickau, after which 12 members were executed in Dresden, and several dozen were imprisoned in Nazi concentration camps, where 37 of them died.[9] In May 1942, five Polish students of the Salesian Oratory in Poznań, known as the Poznań Five or five of the 108 Blessed Polish Martyrs of World War II, were imprisoned in Zwickau, before being executed in Dresden.[10] A subcamp of the Flossenbürg concentration camp was located in Zwickau, whose prisoners were mostly Poles and Russians, but also Italians, French, Hungarians, Jews, Czechs, Germans and others.[11]

On 17 April 1945, US troops entered the city. They withdrew on 30 June 1945 and handed Zwickau to the Soviet Red Army. Between 1944 and 2003, the city had a population of over 100,000.

A major employer is Volkswagen which assembles its ID.3, ID.4 and ID.5 models, as well as Audi and Cupra EV's in the Zwickau-Mosel vehicle plant.

Economic history

[edit]

Coal mining

[edit]Coal mining is mentioned as early as 1348.[8] However, mining on an industrial scale first started in the early 19th century. The coal mines of Zwickau and the neighbouring Oelsnitz-Lugau coalfield contributed significantly to the industrialisation of the region and the city.

In 1885 Carl Wolf invented an improved gas-detecting safety mining-lamp. He held the first world patent for it. Together with his business partner Friemann he founded the "Friemann & Wolf" factory. Coal mining ceased in 1978. About 230 million tonnes had been mined to a depth of over 1,000 metres. In 1992 Zwickau's last coke oven plant was closed.

Many industrial branches developed in the city in the wake of the coal mining industry: mining equipment, iron and steel works, textile, machinery in addition to chemical, porcelain, paper, glass, dyestuffs, wire goods, tinware, stockings, and curtains. There were also steam saw-mills, diamond and glass polishing works, iron-foundries, and breweries.

Automotive industry

[edit]In 1904 the Horch automobile plant was founded, followed by the Audi factory in 1909. In 1932 both brands were incorporated into Auto Union but retained their independent trademarks. Auto Union racing cars, developed by Ferdinand Porsche and Robert Eberan von Eberhorst, driven by Bernd Rosemeyer, Hans Stuck, Tazio Nuvolari, Ernst von Delius, became well known nationally and internationally. During World War II, the Nazi government operated a satellite camp of the Flossenbürg concentration camp in Zwickau which was sited near the Horch Auto Union plant. The Nazi administration built a hard labour prison camp at Osterstein Castle. Both camps were liberated by the US Army in 1945. On 1 August 1945 military administration was handed over to the Soviet Army. The Auto Union factories of Horch and Audi were dismantled by the Soviets; Auto Union relocated to Ingolstadt, Bavaria, evolving into the present day Audi company. In 1948 all large companies were seized by the East German government.

With the founding of the German Democratic Republic in 1949 in East Germany, post-war reconstruction began. In 1958 the Horch and Audi factories were merged into the Sachsenring plant. At the Sachsenring automotive plant the compact Trabant cars were manufactured. These small cars had a two-cylinder, two-stroke engine. The car was the first vehicle in the world to be industrially manufactured with a plastic car body. The production of the Trabant was discontinued after German reunification, but Volkswagen built a new factory in the nearby Mosel area to the north of the city and Sachsenring is now a supplier for the automobile industry. The former VEB Sachsenring manufacturing site was acquired by Volkswagen in 1990 and has since been redeveloped as an engine and transmission manufacturing facility. Nowadays the headquarters of Volkswagen-Saxony Ltd. (a VW subsidiary) is in the northern part of Zwickau.

Audi together with the city of Zwickau operates the August Horch Museum in the former Audi works. In 2021, production of the Audi Q4 e-tron began at the Zwickau-Mosel plant, marking the return of the manufacture of Audi badged cars in Zwickau for the first time in over 80 years.

Uranium mining

[edit]Two major industrial facilities of the Soviet SDAG Wismut were situated in the city: the uranium mill in Zwickau-Crossen, producing uranium concentrate from ores mined in the Erzgebirge and Thuringia, and the machine building plant in Zwickau-Cainsdorf producing equipment for the uranium mines and mills of East Germany. Uranium milling ended in 1989, and after the unification the Wismut machine building plant was sold to a private investor.

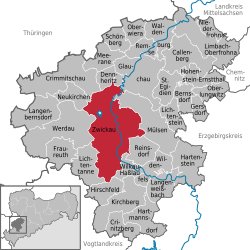

Boundaries

[edit]Zwickau is bounded by Mülsen, Reinsdorf, Wilkau-Hasslau, Hirschfeld (Verwaltungsgemeinschaft Kirchberg), Lichtentanne, Werdau, Neukirchen, Crimmitschau, Dennheritz (Verwaltungsgemeinschaft Crimmitschau), and the city of Glauchau.

Incorporations

[edit]- 1895: Pölbitz

- 1902: Marienthal

- 1905: Eckersbach

- 1922: Weissenborn

- 1923: Schedewitz

- 1939: Brand and Bockwa

- 1944: Oberhohndorf and Planitz

- 1953: Auerbach, Pöhlau, and Niederhohndorf

- 1993: Hartmannsdorf

- 1996: Rottmannsdorf

- 1996: Crossen (with 4 municipalities on 1 January 1994, Schneppendorf)

- 1999: Cainsdorf, Mosel, Oberrothenbach, and Schlunzig, along with Hüttelsgrün (Lichtentanne) and Freiheitssiedlung

Population

[edit]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1462 | 3,900 | — |

| 1530 | 7,677 | +96.8% |

| 1640 | 2,693 | −64.9% |

| 1723 | 3,753 | +39.4% |

| 1800 | 4,189 | +11.6% |

| 1840 | 9,740 | +132.5% |

| 1861 | 20,492 | +110.4% |

| 1871 | 27,322 | +33.3% |

| 1875 | 31,491 | +15.3% |

| 1890 | 44,198 | +40.4% |

| 1900 | 55,825 | +26.3% |

| 1905 | 68,502 | +22.7% |

| 1910 | 73,542 | +7.4% |

| 1925 | 80,358 | +9.3% |

| 1933 | 84,701 | +5.4% |

| 1939 | 85,198 | +0.6% |

| 1946 | 122,862 | +44.2% |

| 1950 | 138,844 | +13.0% |

| 1960 | 129,138 | −7.0% |

| 1972 | 124,796 | −3.4% |

| 1981 | 121,800 | −2.4% |

| 1990 | 122,979 | +1.0% |

| 2001 | 101,726 | −17.3% |

| 2011 | 93,081 | −8.5% |

| 2022 | 87,020 | −6.5% |

| Source: Census data for 1875 to 1939 | ||

Education

[edit]Zwickau is home to the University of Applied Sciences Zwickau, with about 4,700 students and two campuses within the boundaries of Zwickau.

Dr. Martin Luther School (German: Dr. Martin Luther Schule) is a grade 1–4 school of the Evangelical Lutheran Free Church in Zwickau.[12]

Politics

[edit]Mayor and city council

[edit]The first freely elected mayor after German reunification was Rainer Eichhorn of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), who served from 1990 to 2001. The mayor was originally chosen by the city council, but since 1994 has been directly elected. Dietmar Vettermann, also of the CDU, served from 2001 until 2008. He was succeeded by Pia Findeiß of the Social Democratic Party (SPD), who was in office until 2020. The most recent mayoral election was held on 20 September 2020, with a runoff held on 11 October, at which Constance Arndt (Bürger für Zwickau) was elected.[1]

| Candidate | Party | First round | Second round | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Votes | % | |||

| Kathrin Köhler | Christian Democratic Union | 9,453 | 31.5 | 7,549 | 28.1 | |

| Constance Arndt | Citizens for Zwickau | 6,506 | 21.7 | 19,358 | 71.9 | |

| Andreas Gerold | Alternative for Germany | 5,109 | 17.0 | Withdrew | ||

| Michael Jakob | Independent | 4,797 | 16.0 | Withdrew | ||

| Ute Manuela Brückner | The Left | 4,183 | 13.9 | Withdrew | ||

| Valid votes | 30,048 | 99.3 | 26,907 | 99.1 | ||

| Invalid votes | 204 | 0.7 | 246 | 0.9 | ||

| Total | 30,252 | 100.0 | 27,153 | 100.0 | ||

| Electorate/voter turnout | 72,225 | 41.9 | 72,085 | 37.7 | ||

| Source: City of Zwickau (1st round, 2nd round) | ||||||

The most recent city council election was held on 9 June 2024, and the results were as follows:

| Party | Votes | % | +/- | Seats | +/- | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative for Germany (AfD) | 38,740 | 32.3 | 16 | |||

| Christian Democratic Union (CDU) | 24,937 | 20.8 | 10 | |||

| Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance (BSW) | 15,593 | 13.0 | New | 6 | New | |

| Citizens for Zwickau (BfZ) | 14,970 | 12.5 | 6 | |||

| Social Democratic Party (SPD) | 8,304 | 6.9 | 3 | |||

| The Left (Die Linke) | 5,312 | 4.4 | 2 | |||

| Alliance 90/The Greens (Grüne) | 3,823 | 3.2 | 2 | |||

| Free Democratic Party (FDP) | 3,702 | 3.1 | 1 | |||

| Free Saxons (FS) | 2,823 | 2.4 | New | 1 | New | |

| Shaping Zwickau Together (2ZG) | 1,816 | 1.5 | New | 1 | New | |

| Valid votes | 120,020 | 100.0 | ||||

| Total ballots | 42,623 | 100.0 | 48 | ±0 | ||

| Electorate/voter turnout | 68,766 | 62.0 | ||||

| Source: City of Zwickau | ||||||

Historical mayors

[edit]

- 1501–1518: Erasmus Stella

- 1518–1530: Hermann Mühlpfort

- 1800, 1802, 1804, 1806, 1808, 1810, 1812, 1814: Carl Wilhelm Ferber

- 1801, 1803, 1805, 1807, 1809, 1811, 1813, 1815, 1817, 1819: Tobias Hempel

- 1816, 1818, 1820, 1822: Christian Gottlieb Haugk

- 1821, 1823, 1825, 1826: Carl Heinrich Rappius

- 1824: Christian Heinrich Pinther

- 1827–1830: Christian Heinrich Mühlmann, Stadtvogt

- 1830–1832: Franz Adolf Marbach

- 1832–1860: Friedrich Wilhelm Meyer

- 1860–1898: Lothar Streit, from 1874 Lord Mayor

- 1898–1919: Karl Keil

- 1919–1934: Richard Holz

- 1934–1945: Ewald Dost

- 1945: Fritz Weber (acting Lord Mayor)

- 1945: Georg Ulrich Handke (1894–1962) (acting Lord Mayor)

- 1945–1949: Paul Müller

- 1949–1954: Otto Assmann (1901–1977)

- 1954–1958: Otto Schneider

- 1958–1969: Gustav Seifried

- 1969–1973: Liesbeth Windisch

- 1973–1977: Helmut Repmann

- 1977–1990: Heiner Fischer (1936–2016)

- 1990–2001: Rainer Eichhorn (born 1950)

- 2001–2008: Dietmar Vettermann (born 1957)

- 2008–2020: Pia Findeiss (born 1956)

- 2020 until now: Constance Arndt (born 1977)

Sports

[edit]Transport

[edit]

The city is close to the A4 (Dresden-Erfurt) and A72 (Hof-Chemnitz) Autobahns.

Zwickau Hauptbahnhof is on the Dresden–Werdau line, part of the Saxon-Franconian trunk line, connecting Nuremberg and Dresden. There are further railway connections to Leipzig as well as Karlovy Vary and Cheb in the Czech Republic. The core element of Zwickau's urban public transport system is the Zwickau tramway network; the system is also the prototype of the so-called Zwickau Model for such systems.

The closest airport is Leipzig-Altenburg, which has no scheduled commercial flights. The nearest major airports are Leipzig/Halle Airport and Dresden Airport, both of which offer a large number of national and international flights.

Museums

[edit]

In the city centre there are three museums: an art museum from the 19th century and the houses of priests from 13th century, both located next to St. Mary's church. Just around the corner there is the Robert-Schumann museum. The museums offer different collections dedicated to the history of the city, as well as art and a mineralogical, palaeontological and geological collection with many specimens from the city and the nearby Ore Mountains.

Zwickau is the birthplace of the composer Robert Schumann. The house where he was born in 1810 still stands in the marketplace. This is now called Robert Schumann House and is a museum dedicated to him.

The histories of the Audi and Horch automobile factories are presented at the August Horch Museum Zwickau. The museum is an Anchor Point of the European Route of Industrial Heritage (EIRH).

Notable people

[edit]

Born before 1900

[edit]- Nicholas Storch (before 1500 – after 1536), weaver and lay preacher (Zwickau Prophets)

- Janus Cornarius (c. 1500–1558), philologist and physician

- Gregor Haloander (1501–1531), jurist

- David Köler (1532–1565), musician, organist, choirmaster and composer

- Jacob Leupold (1674–1727), mechanic and instrument maker

- Robert Schumann (1810–1856), composer of the Romantic era

- Paul Emil Flechsig (1847–1929) neuroanatomist, psychiatrist and neuropathologist

- Heinrich Schurtz (1863–1903), ethnologist and historian

- August Horch (1868–1952), automotive engineer

- Heinrich Waentig (1870–1943), economist and politician (SPD)

- Hans Dominik (1872–1945), writer, journalist and engineer

- Fritz Bleyl (1880–1966), Expressionist painter and architect

- Max Pechstein (1881–1955), Expressionist painter

- "Margaret Scott" (1888–1973), militant suffragette in London

- Paul Langheinrich (1895–1979), genealogist

Born after 1900

[edit]

- Gerhard Küntscher (1900–1972), orthopedic surgeon and inventor of the modern intramedullary nailing procedure to treat long bone fractures

- Robert Eberan von Eberhorst (1902–1982), Austrian automotive engineer

- Gershom Schocken (1912–1990), Israeli journalist and politician

- Gert Fröbe (1913–1988), actor

- Gerhard Schürer (1921–2010), politician (SED)

- Erhard Weller (1926–1986), actor

- Rolf Hädrich (1931–2000), film director and screenwriter

- Dieter F. Uchtdorf (born 1940), Second Counselor in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. He lived here following World War II.

- Harald Fritzsch (1943–2022), theoretical physicist (quantum theory)

- Volkmar Weiss (born 1944), geneticists, social historian and genealogist

- Jürgen Croy (born 1946), footballer

- Christoph Bergner (born 1948), politician (CDU), 1993–1994 Prime Minister of Saxony-Anhalt

- Eckart Viehweg (1948–2010), mathematician

- Hagen von Ortloff (born 1949), TV-journalist

- Werner Schulz (1950–2022), politician (Alliance 90/The Greens)

- Frank Petzold (born 1951), composer and conductor

- Christoph Daum (1953–2024), football player and coach

- Lutz Dombrowski (born 1959), athlete and Olympic champion

- Lars Riedel (born 1967), discus thrower

- Sven Günther (born 1974), footballer

- Cathleen Martini (born 1982), bobsledder, world champion

- Marie-Elisabeth Hecker (born 1987), classical cellist

- Danny Röhl (born 1989), football coach

- Kristin Gierisch (born 1990), triple jumper

Twin towns – sister cities

[edit] Jablonec nad Nisou, Czech Republic (1971)

Jablonec nad Nisou, Czech Republic (1971) Zaanstad, Netherlands (1987)

Zaanstad, Netherlands (1987) Dortmund, Germany (1988)

Dortmund, Germany (1988) Volodymyr, Ukraine (2014)

Volodymyr, Ukraine (2014) Yandu (Yancheng), China (2014)

Yandu (Yancheng), China (2014)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Wahlergebnisse 2020, Freistaat Sachsen, accessed 10 July 2021.

- ^ "Bevölkerung der Gemeinden Sachsens am 31. Dezember 2023 - Fortschreibung des Bevölkerungsstandes auf Basis des Zensus vom 15. Mai 2022 (Gebietsstand 01.01.2023)" (in German). Statistisches Landesamt des Freistaates Sachsen.

- ^ "Wirtschaft & Standort" [Industry & Location]. zwickau.de (in German). Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- ^ "How to find us". horch-museum.de. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- ^ ADAC Travel Guide, Towns and Cities from A to Z – City Guide Germany Travel Information, first edition June 2005, 368 pages, ISBN 3-89905-233-1

- ^ "Mulderadweg" [Mulde bike lane] (in German). Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ Zwickau by Stadtbaurat Ebersbach in: Deutschlands Städtebau (Germany's Urban Development), Deutscher Architektur und Industrieverlag Berlin 1921

- ^ a b One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Zwickau". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 1061.

- ^ Wojciech Königsberg (20 August 2015). "Czarny Legion – polska organizacja podziemna rozbita przez Niemców". WP Opinie (in Polish). Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ "Poznańska piątka". Gosc.pl (in Polish). 24 August 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ "Zwickau Subcamp". KZ-Gedenkstätte Flossenbürg. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ "Evangelical Lutheran Free Church—Germany". Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ "Stabsstelle Stadtentwicklung". zwickau.de (in German). Zwickau. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

External links

[edit]- Zwickau Official website (in German)

- August-Horch Museum at Audi Works (in German)

Zwickau

View on GrokipediaGeography

Location and Topography

Zwickau is situated in the Free State of Saxony in eastern Germany, at coordinates 50°43′ N latitude and 12°30′ E longitude.[7] The city lies in the valley of the Zwickauer Mulde river, at the northern foothills of the Ore Mountains (Erzgebirge), forming part of the transition zone between the mountainous Erzgebirge to the south and the hilly Vogtland region to the west.[8] [9] The urban area spans 102.6 km², extending approximately 19 km from north to south and 11 km from east to west.[7] Topographically, Zwickau occupies a lowland valley setting with an average elevation of 267 meters above sea level, surrounded by gently rising hills that reach up to several hundred meters in the vicinity.[10] This terrain reflects the broader geological character of the western Ore Mountains foreland, featuring fluvial plains along the Mulde and undulating slopes shaped by glacial and erosional processes.[11] The city's position within the Chemnitz-Zwickau metropolitan region integrates it into a network of industrial and natural landscapes, with proximity to forested highlands influencing local microclimates and drainage patterns dominated by the northward-flowing Zwickauer Mulde tributary of the larger Mulde river system.[11]Climate and Natural Resources

Zwickau features a temperate oceanic climate (Köppen classification Cfb), marked by mild summers, cool winters, and evenly distributed precipitation without extreme dry seasons.[12] Average annual temperatures range from winter lows around -2°C (28°F) to summer highs near 23°C (74°F), with extremes rarely dropping below -11°C (13°F) or exceeding 29°C (85°F).[13] Precipitation totals approximately 933 mm annually, with monthly averages varying from about 50 mm in drier periods to over 100 mm during wetter months, supporting consistent vegetation growth. The surrounding landscape includes forested hills in the western Ore Mountains foothills, providing timber resources and biodiversity, though historical deforestation from mining has shaped current woodland composition.[14] Geologically, the area holds deposits of hard coal and formerly uranium, which fueled industrial development until extraction halted—coal mining ended in the 1970s under GDR policies, and uranium processing ceased after 1990 due to environmental and economic factors.[15][16] The Zwickauer Mulde river, a major tributary of the Mulde system spanning 166 km, supplies water for local use, irrigation, and ecosystems, though legacy contamination from upstream mining affects floodplain soils.[14][16] Current natural resources emphasize sustainable forestry and river-based recreation over extractive industries, reflecting post-industrial shifts in Saxony's resource management.[14]Demographics

Population Trends and Statistics

As of the 2022 German census, Zwickau had a population of 87,020 residents, reflecting a density of 848 inhabitants per square kilometer across its 102.6 square kilometers.[17] Recent estimates indicate modest growth to 87,410 by 2024, with an annual change of +0.17% between 2022 and 2024, suggesting stabilization following decades of decline.[18] The city's population has contracted significantly since reunification, driven by economic restructuring, out-migration to western Germany, and a persistent natural decrease from low birth rates and higher mortality amid an aging demographic. From 2011 to 2022, the annual decline averaged -0.61%, reducing the population from 93,081 to the 2022 figure.[17] Historical data show a sharper drop post-1990, from 122,979 residents to 101,726 by 2001, consistent with patterns in former East German industrial centers where job losses in mining and manufacturing prompted mass emigration.[18]| Year | Population | Notes/Source |

|---|---|---|

| 1990 (est.) | 122,979 | Pre-census estimate |

| 2001 (est.) | 101,726 | Population register |

| 2011 (census) | 93,081 | Federal census |

| 2022 (census) | 87,020 | Federal census |

| 2024 (est.) | 87,410 | Projection based on registers[18] |

Ethnic and Social Composition

Zwickau's population is overwhelmingly ethnic German, reflecting the broader demographic homogeneity of eastern Germany. As of mid-2019, residents with foreign citizenship accounted for 11.7% of those with primary residence, a figure higher than the Saxon state average but lower than national levels.[21] This includes migrants primarily from EU countries, Turkey, and more recently Syria and other Middle Eastern nations due to asylum inflows, though detailed ethnic breakdowns are not publicly itemized at the city level in official statistics. The low overall immigration rate compared to western German cities stems from historical patterns of limited post-reunification inflows and regional economic factors discouraging settlement.[22] Religiously, Zwickau exhibits high secularization, consistent with trends in former East German territories. The 2022 census recorded 9,531 Protestants (approximately 10.5% of respondents), 2,635 Roman Catholics (about 3%), and 74,855 individuals reporting other affiliations, none, or unknown (86.5%).[17] This marks a decline from the 2011 census, where Protestants comprised 21.7% and non-religious around 75%, underscoring ongoing disaffiliation from organized religion post-GDR era.[23] Socially, the composition features a near-even gender distribution, with 49.2% males and 50.8% females as of recent estimates.[18] As a post-industrial hub with roots in mining and manufacturing, Zwickau retains a pronounced working-class character, with socioeconomic challenges including above-average unemployment (around 5.4% in late 2024 for the electoral district) and reliance on automotive sector jobs.[24] Education levels lag national averages, contributing to income disparities, though recent shifts toward electric vehicle production offer stabilization.[23]History

Medieval Foundations and Early Growth

The region surrounding Zwickau was initially settled by Sorbian Slavs, with the site serving as a trading locale prior to German colonization efforts in the 12th century. The earliest documentary reference to Zwickau appears in a 1118 record as "territorio Zcwickaw," denoting a defined territory associated with commerce along trade routes in the Zwickauer Mulde valley.[25] [26] Zwickau obtained its town charter in 1212, marking the formal establishment of municipal governance and privileges typical of emerging medieval urban centers in the Holy Roman Empire. By the early 13th century, the foundational urban structure—characterized by a market square, surrounding streets, and defensive elements—had taken shape, reflecting organized settlement patterns driven by merchant and artisan influxes. Cloth production emerged as the initial key economic sector, leveraging local resources and regional markets to foster early prosperity.[26] [3] [27] Limited mining activities in the vicinity are attested by a 1316 charter documenting extraction efforts, predating the later silver boom but indicating nascent resource utilization that complemented trade and textile industries. The town's growth during this period was supported by its strategic location, facilitating exchange between Saxon lowlands and upland areas, though it remained subordinate to regional margraviates until achieving brief imperial immediacy in the late 13th century.[28]Mining and Industrial Emergence (16th-19th Centuries)

The discovery of rich silver deposits in nearby Schneeberg in 1470 initiated a mining boom in the Erzgebirge region, transforming Zwickau into a vital commercial center for ore trade and processing. Mining entrepreneurs from the surrounding districts converged on Zwickau's markets to sell silver, cobalt, and bismuth, generating substantial wealth that financed grand patrician houses, churches, and infrastructure expansions.[29] This influx peaked in the 16th century, with Zwickau serving as a distribution hub for refined metals destined for mints and export, supporting a population surge and elevating the city's status as an economic nexus under the Wettin dynasty.[30] By the 17th and 18th centuries, silver yields in the Erzgebirge began declining due to exhausted shallow veins and competition from American imports, shifting Zwickau's economy toward localized coal extraction and traditional cloth production. Coal seams in the Zwickau basin, documented since 1348, were mined on a small scale for local fuel and smithing, but lacked mechanization until steam power's advent.[31] Concurrently, Zwickau's cloth-weaving guilds expanded, leveraging silver-era capital to produce linen and woolens for regional markets, though output remained artisanal and prone to guild regulations.[31] The early 19th century marked Zwickau's industrial takeoff with the large-scale mechanized mining of hard coal, enabled by improved drainage, steam engines, and rail links. The Brückenberg and Morgenstern shafts, operational from the 1840s, yielded over 1 million tons annually by mid-century, fueling factories and drawing migrant labor that doubled the population between 1800 and 1870.[31] This coal-driven expansion spurred ancillary industries like machine works and textiles, with steam-powered looms in local mills boosting cloth output, though economic volatility from pit accidents and market fluctuations persisted.[32]World Wars, Nazi Era, and Post-War Division

During World War I, Zwickau served as the site of a prisoner-of-war camp that housed up to 10,000 Allied captives, primarily engaged in labor supporting the German war economy through local mining and industrial activities.[33] Conditions in the camp included documented instances of punishment and escape attempts, such as tunneling by prisoners with mining expertise.[34] Under the Nazi regime from 1933, Zwickau's Jewish community faced systematic persecution, including the destruction of the synagogue and deportations leading to the deaths of local Jews, as commemorated by post-war memorials.[35] The city's industries, particularly the Horch-Werke (later Auto-Union), were repurposed for armaments production, attracting Allied bombing raids targeting aircraft repair facilities and marshalling yards in 1944 and 1945, such as missions on April 12 and 21, 1944.[36][37] From August 30, 1944, to April 15, 1945, a subcamp of Flossenbürg concentration camp operated in Zwickau, detaining over 1,000 male prisoners—predominantly Poles (437, including 30 Jews), Russians (306), Italians (85), French (over 70), and others from nine nationalities—for forced labor in vehicle, airplane, and torpedo production at Auto-Union facilities.[38] Harsh conditions sparked epidemics, resulting in over 350 transfers to the main camp and at least 280 recorded deaths, with many more perishing post-evacuation.[38] Zwickau was captured by the U.S. 89th Infantry Division on April 17-18, 1945, following failed surrender negotiations and intense urban combat involving small arms, automatic weapons, Panzerfausts, and bazooka fire; the 1st Battalion, 355th Infantry secured key bridges over the Zwickauer Mulde river, freeing 200 British POWs amid the advance.[39] As part of Saxony, the city was transferred to Soviet control per Allied agreements, falling within the Soviet Occupation Zone (SBZ) established in 1945.[40] This zone, encompassing Saxony, formed the basis for the German Democratic Republic (GDR) upon its founding on October 7, 1949, initiating Zwickau's integration into the socialist East German state.[40] Soviet troops occupied local installations, marking the onset of divided Germany's ideological and administrative separation.[41]GDR Period: State Socialism and Economic Specialization

Following the formation of the German Democratic Republic on October 7, 1949, Zwickau's industries were nationalized under the Socialist Unity Party of Germany's (SED) central planning directives, transforming private enterprises into state-owned Volkseigene Betriebe (VEBs) to align with socialist economic principles.[42] This shift prioritized heavy industry and resource extraction to fulfill quotas for the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON), emphasizing output for intra-bloc trade over consumer needs or technological advancement. Local coal mining, a longstanding economic driver, was integrated into state combines, with production focused on hard coal extraction despite rising costs and depleting seams.[43] Zwickau's coal sector, operational since medieval times, saw continued but diminishing output during the GDR era, contributing to national hard coal totals amid broader inefficiencies in socialist resource allocation. The Zwickau coalfield yielded significant volumes until unprofitability forced closures; mining ceased entirely by 1977 after approximately 800 years, with cumulative extraction from 1850 to 1978 reaching 207 million metric tons, a portion of which supported GDR energy demands under rigid production targets.[23] [44] State-directed specialization redirected labor and capital toward automotive manufacturing as mining waned, leveraging pre-war facilities like the former Horch and Audi works to establish Zwickau as a key producer of small vehicles for the socialist market.[45] The VEB Sachsenring Automobilwerke Zwickau epitomized this economic reorientation, launching Trabant production in 1957 as a standardized, affordable car for the masses, with the model series continuing until 1991. Over 3 million Trabants were built, peaking at models like the 601 from 1963, serving primarily domestic users and exports to allied states while exemplifying central planning's emphasis on mass output using synthetic duroplast bodies to conserve metal.[46] [47] However, chronic shortages, decade-long waiting lists, and outdated two-stroke engines underscored the system's technological lag and prioritization of ideological conformity over efficiency or innovation.[48] By the 1980s, Zwickau's specialization in automotive assembly and residual mining supported SED goals of industrial self-sufficiency, yet underlying structural rigidities contributed to economic stagnation evident at reunification.[49]Reunification, Deindustrialization, and Recovery (1990-Present)

Following German reunification on October 3, 1990, Zwickau experienced severe economic disruption as East German state-owned enterprises, uncompetitive in a market economy, faced rapid privatization and closure under the Treuhandanstalt agency. The Trabant automobile factory, which had employed thousands producing over 3 million vehicles during the GDR era, ceased operations in April 1991 after failing to adapt, contributing to immediate job losses exceeding 20% unemployment in the region by the late 1990s.[50][46] Mining sectors, including lignite coal, also contracted sharply as subsidies ended and environmental regulations tightened, exacerbating deindustrialization.[51] Population decline accelerated during this period, with Zwickau's residents dropping from a GDR peak of around 140,000 to approximately 88,000 by 2025, driven by out-migration of working-age individuals seeking opportunities in western Germany or abroad amid economic uncertainty.[51][15] This shrinkage reflected broader East German trends, where inefficient socialist-era industries collapsed, leading to a loss of over 4 million jobs nationwide in manufacturing and extraction by the mid-1990s.[52] Recovery began in the early 2000s through foreign investment, particularly Volkswagen's 1990 acquisition and modernization of the former Trabant plant in Zwickau-Mosel, which shifted to producing conventional vehicles like the Golf and Passat, eventually delivering around 6 million units by 2010.[50] By 2020, the facility transitioned to electric vehicle production, including assembly of models for Volkswagen, Audi, and Cupra, while also manufacturing bodies for luxury Volkswagen Group models such as the Bentley Bentayga and Lamborghini Urus, employing over 10,000 workers and positioning Zwickau as a key hub in Germany's e-mobility strategy.[53][54] This pivot supported employment stabilization, with regional unemployment falling below national averages in recent years, though vulnerabilities persist, as evidenced by Volkswagen's 2024 announcement of potential cuts threatening 1,000 jobs amid global EV market challenges.[51] Urban renewal efforts, including infrastructure upgrades funded by federal solidarity pacts totaling over €2 trillion for eastern Germany since 1990, have aided diversification into logistics and services, fostering modest GDP per capita growth despite ongoing east-west disparities.[55]Economy

Resource Extraction: Coal, Silver, and Uranium Mining

Zwickau's medieval prosperity was closely tied to silver mining in the adjacent Erzgebirge region, where deposits were exploited starting in the 12th century. The city's first economic boom occurred after silver discoveries in Schneeberg in 1470, attracting mining entrepreneurs who traded ore and enriched local commerce.[29][56] Coal extraction in the Zwickau area dates to at least 1348, with initial small-scale operations giving way to industrial mining in the early 19th century enabled by advancements like steam-powered drainage and ventilation. The Carboniferous coalfield, spanning roughly 92 km² around Zwickau, yielded approximately 230 million tonnes of hard coal by closure in 1978, extracted from depths exceeding 1,000 meters.[31][57] This sector dominated the local economy for over 600 years, shaping urban development and employing thousands until economic unviability led to abandonment.[32] During the German Democratic Republic (GDR) period, Zwickau served as a key site for the Soviet-German Wismut enterprise, which oversaw uranium production from 1947 to 1990 primarily in Saxony and Thuringia to fuel Soviet nuclear programs. While primary ore extraction focused on areas like Aue in the Erzgebirge, Zwickau hosted major Wismut facilities, including a tailing management plant for regional mines and a chemical processing works producing yellowcake concentrate in the Seilerstraße.[58][59] Wismut's operations across East Germany totaled over 230,000 tonnes of uranium, but left extensive environmental legacies in Zwickau, such as contaminated tailings and ongoing remediation efforts costing billions of euros into the 21st century.[59][60]Automotive Manufacturing: From Trabant to Electric Vehicles

The VEB Sachsenring Automobilwerke Zwickau, established on the site of pre-World War II Auto Union factories, began production of the Trabant P50 small car on November 7, 1957, marking the start of East Germany's primary automotive output under state socialism.[61] The Trabant series, featuring a durable Duroplast body made from recycled materials including cotton waste reinforced with phenolic resin, became the dominant vehicle for East German citizens, with over 3 million units produced by 1991 despite chronic shortages and long waiting lists averaging 10-15 years.[62] Powered by a two-stroke 500 cc engine initially producing 18 horsepower, later models like the Trabant 601 from 1963 offered modest upgrades but retained outdated technology due to GDR resource constraints and isolation from Western innovations.[61] Production ceased on April 30, 1991, following German reunification, as the inefficient Trabant failed to compete in a market economy, leading to rapid deindustrialization and unemployment peaking at over 20% in Zwickau by the mid-1990s.[47] The facility underwent modernization, with Volkswagen Group acquiring portions in the early 1990s to produce engines, components, and body parts, sustaining partial employment while adapting to capitalist demands; by 2005, it supplied parts for Audi models, leveraging the site's engineering legacy.[63] In 2017, Volkswagen selected Zwickau as its primary European hub for electric vehicle manufacturing, investing over €2 billion to convert the plant for the Modular Electric Drive Matrix (MEB) platform, with serial production of the ID.3 commencing on November 4, 2019.[61] By April 30, 2025, the plant had produced its one-millionth electric vehicle across six models from Volkswagen, Audi, and Cupra brands, achieving a capacity of up to 330,000 units annually through automated processes and battery integration.[64] Despite this growth, production pauses occurred in October 2025 due to softening EV demand amid subsidy reductions and competition, highlighting vulnerabilities in the sector's reliance on policy support.[65]Current Sectors, Employment, and Challenges

The automotive industry remains the dominant sector in Zwickau's economy, centered on the Volkswagen plant, which has pioneered electric vehicle production within the group since launching the ID.3 in 2019. The facility directly employs over 10,000 workers and sustains tens of thousands more jobs in ancillary supply chains, contributing significantly to regional output.[50] Complementary manufacturing sectors include mechanical engineering, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and metalworking, alongside growing trade and logistics activities tied to industrial clusters.[66] Total employment in Zwickau has shown resilience post-reunification, reaching approximately 52,800 persons in 2016 after a 14.4% increase since 2008, with recent stability amid Saxony's overall employment rate of 78.3% in 2024.[67][68] The local unemployment rate stands at 5.5% as of late 2024, exceeding the Saxon average of 3.8% and reflecting structural frictions in industrial transition.[51] Gross domestic product per employee in the Zwickau district lags behind national figures at around €55,900, underscoring lower productivity compared to western Germany.[69] Key challenges stem from heavy reliance on Volkswagen amid the electric vehicle shift, with demand shortfalls prompting workforce reductions, including the non-renewal of 1,000 temporary contracts by end-2025 and weekly production halts in 2025.[70][65] These measures signal broader automotive sector pressures, including stalled e-mobility adoption and potential for further job losses estimated in the thousands across eastern German plants.[71][72] Lingering effects of 1990s deindustrialization, such as population decline to 87,000 residents and limited diversification, exacerbate vulnerabilities to cyclical downturns and hinder skill adaptation in a shifting labor market.[51]Government and Politics

Municipal Structure and Leadership

Zwickau's municipal government operates under the Sächsische Gemeindeordnung, with the Stadtrat serving as the primary legislative body representing citizens' interests. The council comprises 48 elected members plus the Oberbürgermeisterin as chairperson, determining the number based on the city's population of approximately 88,000. Members are elected every five years through proportional representation, with the latest election occurring on 9 June 2024 and a voter turnout of 62.0%. [73] [74] The executive leadership is headed by the directly elected Oberbürgermeisterin, Constance Arndt of the local Bürger für Zwickau group, who assumed office on 17 November 2020 following a runoff election. [75] Arndt oversees administration, represents the city externally, and chairs council meetings, with authority to veto decisions subject to council override. Supporting her are appointed Beigeordnete (deputy mayors), including Silvia Queck-Hänel for construction and urban development and Sebastian Lasch for finance and public order, who manage specific departments. [76] Administrative operations are divided into departments (Ämter) handling areas such as education, social services, public utilities, and economic development, coordinated under the Oberbürgermeisterin's office. The structure emphasizes citizen participation through public consultations and advisory committees, though decision-making power resides with the elected bodies. Zwickau, as a Große Kreisstadt and seat of the Landkreis Zwickau, coordinates with district-level authorities on regional matters while retaining autonomy in local governance. [77]Electoral Dynamics and Far-Right Presence

In municipal elections, the Alternative for Germany (AfD) has emerged as a dominant force in Zwickau, surpassing the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) in the 2024 city council vote and securing the largest share of seats in the new Stadtrat, reflecting voter dissatisfaction with established parties amid economic stagnation and migration concerns.[78] In the preceding 2019 local elections, AfD obtained approximately 28.7% in key Zwickau precincts, contributing to its statewide gain of 21.2% across Saxon municipalities.[79] At the state level, Zwickau's electoral districts demonstrate AfD's strength in first-past-the-post contests, with party candidates winning direct mandates in Wahlkreis Zwickau 3 (36.7% of first votes for Jonas Dünzel) and Zwickau 5 (34.6% for Mike Moncsek) during the September 1, 2024, Saxony Landtag election.[80][81] List vote shares underscored this, at 32.6% in Zwickau 3 (edging CDU's 32.5%) and 31.8% in Zwickau 5 (behind CDU's 35.3%), exceeding the party's statewide 30.6% amid a record 74.5% turnout driven by anti-establishment sentiment.[80][81][82] Federal and European polls reinforce Zwickau's alignment with eastern German patterns of AfD dominance, fueled by post-reunification deindustrialization, persistent youth unemployment above 7%, and perceptions of unchecked immigration straining local resources.[83] In the June 2024 European Parliament election, AfD captured 34.8% in Zwickau district, outpacing CDU's 23.2% and dwarfing SPD's 6.5%.[84] This electoral foothold for AfD, classified by Saxony's domestic intelligence as a suspected right-wing extremist entity due to radical factions within its state branch, signals a mainstream channel for far-right views on national identity and EU skepticism, though overt neo-Nazi groups like NPD polled below 1% (0.34% in 2019 local races).[79] Despite AfD's advances, coalitions excluding it persist; Saxony's CDU-SPD minority government, formed December 2024, mirrors Zwickau's local dynamics where CDU retains influence but struggles against AfD's protest vote base.[85] Voter turnout spikes and AfD gains correlate with causal factors like factory closures (e.g., VW's Zwickau plant uncertainties) and cultural alienation in former GDR areas, rather than isolated ideological extremism.[86][87]NSU Terror Cell: Operations, Discoveries, and Institutional Failures

The Nationalsozialistischer Untergrund (NSU), a neo-Nazi terrorist group centered in Zwickau, Saxony, operated underground from 1998 after its core members—Uwe Mundlos, Uwe Böhnhardt, and Beate Zschäpe—evaded arrest for illegal bomb production and fled Jena.[88] The trio resided at Frühlingsstraße 26 in Zwickau, sustaining themselves through approximately 15 bank robberies across Germany between 1999 and 2011, which provided funding for their activities.[89] Their operations included a string of nine murders targeting individuals of Turkish, Greek, or other immigrant backgrounds—primarily small business owners—between September 2000 and June 2006, executed methodically with a single Česká 83 pistol to evade detection; victims included Enver Şimşek (stabbed and shot in Nuremberg, 2000), Abdurrahim Özüdoğru (shot in Nuremberg, 2001), and others in cities like Munich, Hamburg, and Dortmund.[90] [89] In April 2007, they killed police officer Michèle Kiesewetter in Heilbronn, shooting her at close range and severely wounding her partner, marking a shift to targeting state representatives.[91] The group also conducted two major bombings: pipe bombs in 1999 and a nail bomb attack in Cologne's Keupstraße in June 2004, which injured 22 people and damaged multiple buildings.[89] These acts were ideologically driven by racial animosity, as later evidenced by NSU propaganda materials.[91] The NSU's exposure occurred on November 4, 2011, when Mundlos and Böhnhardt robbed a bank in Eisenach, Thuringia; pursuing police discovered their bodies in a nearby caravan alongside two firearms and the murder weapon, with autopsies indicating suicide by gunshot.[92] Zschäpe surrendered to authorities on November 11, 2011, after confessing to involvement and setting fire to the Zwickau apartment to destroy evidence; the blaze yielded remnants including 11 firearms (10 handguns and one machine pistol), explosives, over 2.5 kilograms of ammunition, neo-Nazi literature, and a data storage device containing a 90-minute propaganda video.[89] [91] The video, released publicly in November 2011, featured a cartoon character named "Bulleke" (mocking police) claiming responsibility for the murders and bombings, explicitly linking them under the NSU banner and framing them as racially motivated "war" against immigrants and the state.[92] Investigations post-exposure confirmed the pistol's serial traceability to prior NSU-linked crimes, unraveling the decade-long evasion.[91] Zschäpe was convicted in 2018 of complicity in the 10 murders, bombings, and robberies, receiving a life sentence, though the trial highlighted unresolved questions about broader network support.[93] Institutional failures profoundly enabled the NSU's longevity, as German police and intelligence agencies systematically dismissed right-wing extremist motives despite evidentiary leads.[94] Investigations into the murders, dubbed the "Döner-Killer" cases due to victims' ties to kebab shops, fixated on intra-ethnic criminality among immigrants, pressuring victims' families as suspects while ignoring neo-Nazi informants' tips about Mundlos and Böhnhardt's whereabouts and activities.[95] Domestic intelligence (Verfassungsschutz) maintained paid informants embedded in Thuringian neo-Nazi circles, including figures like Tino Brandt who met NSU members multiple times, yet failed to act on reports or share them effectively with police, prioritizing informant protection over threat disruption.[89] In Zwickau, local surveillance overlooked the group's 13-year presence in a residential area, with neighbors noting no overt suspicions despite occasional sightings.[92] Compounding this, Verfassungsschutz offices destroyed hundreds of NSU-related files in the weeks before the 2011 exposure, citing routine procedures but fueling accusations of obstruction; parliamentary inquiries later deemed these lapses a "total failure" of state security apparatus, underestimating right-wing terrorism amid focus on Islamist and left-wing threats.[94] [89] These shortcomings stemmed from fragmented agency coordination, inadequate right-wing extremism monitoring post-Cold War, and a reluctance to acknowledge persistent neo-Nazi networks in eastern Germany, allowing the cell to operate with impunity.[96]Culture and Education

Educational Institutions and Research

The primary higher education institution in Zwickau is the Westsächsische Hochschule Zwickau (WHZ), a university of applied sciences established in 1992 through the merger of predecessor technical colleges dating back to 1897, with approximately 3,500 students enrolled across its campuses.[97][98] The WHZ comprises eight faculties offering around 50 degree programs in fields such as technology, economics, arts, and life sciences, emphasizing practical training aligned with regional industries like automotive engineering and mobility.[97] Over 1,000 international students from more than 50 countries contribute to its diverse student body, supported by partnerships with global universities for exchange and collaborative projects.[99] WHZ positions itself as a research-oriented institution where applied scientific findings directly inform teaching and benefit small- and medium-sized enterprises in Saxony, with key focuses including electric mobility, digitization, energy transition, and globalization.[100][101] Internal and external collaborations drive application-oriented projects addressing economic and societal challenges, as highlighted in university publications like the "Campusforschung" magazine.[101] Within WHZ, the Imaging Centre Zwickau (ICZ) coordinates interdisciplinary research groups specializing in imaging technologies, fostering innovations in data processing and visualization for industrial use.[102] Complementing university efforts, the Fraunhofer Application Center for Optical Metrology AZOM, operational in Zwickau since around 2015 as part of the Fraunhofer Institute for Material and Beam Technology IWS, advances research in optical metrology, surface characterization, image processing, and process control tailored to manufacturing sectors like automotive and mechanical engineering.[103][104] This center emphasizes rapid transfer of research results into customized industrial solutions, evaluating positively in 2021 for its alignment with client needs unmet by standard technologies.[105]Museums, Arts, and Historical Sites

The Robert Schumann House, situated at the site of the composer's birth on June 8, 1810, functions as a dedicated museum, concert hall, and research center preserving the world's largest collection of Robert Schumann's manuscripts, original portraits, personal belongings, and those of his wife Clara Wieck-Schumann.[106] The facility, established in 1956 following reconstruction of the original building destroyed in World War II, features eight exhibition rooms with permanent displays of instruments, prints, and memorabilia, last redesigned in 2011 to highlight Schumann's life, works, and era.[106] Its archive emphasizes autobiographical, literary, and musical documents, supporting scholarly research on Romantic-era composition.[107] The Kunstsammlungen Zwickau, encompassing the Max Pechstein Museum, maintains municipal collections of fine arts spanning late Gothic altarpieces to 20th-century Expressionism, with a focus on native son Max Pechstein's paintings and graphics alongside natural history specimens like minerals from local mining.[108] Housed across historic venues including the former Dominican monastery, these holdings originated in the 19th century with antiquities, sacred art, and Schumann artifacts before expanding under municipal patronage.[108] The collections underscore Zwickau's ties to regional artists from the Dresden Secession group, integrating Expressionist works with geological exhibits tied to the city's industrial past.[109] Historical sites feature the Priesterhäuser, a cluster of 13th-century timber-framed houses originally inhabited by cathedral clergy, now adapted as a museum illustrating medieval domestic architecture and urban life in medieval Saxony.[6] St. Marien Cathedral, a late-Gothic hall church constructed primarily between 1426 and 1453, exemplifies brick Gothic style with its towering spire and interior furnishings, serving as a central religious and architectural landmark.[110] Ruins of Osterstein Castle, dating to the 12th century and later used as a residence and prison until its partial destruction in 1554, offer remnants of medieval fortifications overlooking the Zwickauer Mulde river valley.[111] Arts institutions include the Galerie am Domhof, established in 1878 as an exhibition space for the Zwickauer Kunstverein, which hosts temporary shows of contemporary visual arts and regional talents in a neoclassical setting adjacent to the cathedral.[112] The Gewandhaus Zwickau, a historic concert venue, supports classical music performances tied to Schumann's legacy, while the broader cultural landscape preserves sites like the Denkmal to Robert Schumann, commemorating his influence on Romantic music.[6]Notable Cultural Contributions and Figures

Zwickau is internationally recognized for its contributions to Romantic music through the legacy of composer Robert Schumann, born on June 8, 1810, at Hauptmarkt 5 in the city center.[106] Schumann developed as a pivotal figure in the early Romantic period, producing influential works across piano sonatas, lieder, symphonies, and chamber music, often characterized by emotional depth and structural innovation.[113] The city preserves his birthplace as the Robert Schumann House museum, which holds the world's largest collection of his autographs, letters, and personal artifacts, drawing scholars and enthusiasts annually.[106] To honor his impact, Zwickau established the Robert Schumann Prize in 1964, awarded by the lord mayor typically on June 8 to musicians exemplifying his artistic spirit.[114] The city further promotes his oeuvre via the International Robert Schumann Competition for pianists and singers, initiated in 1956 to commemorate the centennial of his death, fostering young talent in interpreting his compositions.[115] In visual arts, Zwickau contributed to German Expressionism through Fritz Bleyl, born April 6, 1880, who co-founded the Die Brücke artists' group in Dresden in 1905, emphasizing raw emotion and simplified forms in woodcuts and paintings that challenged academic traditions.[116] Bleyl's architectural training and early sketches influenced the group's urban motifs and communal ethos, marking a shift toward modernist abstraction in early 20th-century Germany. The performing arts saw contributions from actor Gert Fröbe, born February 25, 1913, renowned for his commanding presence in theater and film, including the role of Auric Goldfinger in the 1964 James Bond production Goldfinger and the lead in The Golem (1961).[116] Fröbe's career spanned over 100 roles, blending gravitas with humor, and elevated post-war German cinema's global profile. Earlier, actress Caroline Neuber, born March 9, 1697, pioneered reforms in German theater by advocating natural acting styles and ensemble discipline, earning her title as the "Mother of the German Stage" for elevating dramatic art from commedia dell'arte influences in the 18th century.[117] These figures underscore Zwickau's role in nurturing talents that advanced musical innovation, expressive visual styles, and theatrical realism, with institutions like the Gewandhaus concert hall continuing to host performances rooted in this heritage.[118]Infrastructure

Transportation Systems

Zwickau is connected to the national road network primarily through the federal motorways A4 (Dresden–Erfurt) approximately 15 kilometers to the north and A72 (Hof–Chemnitz–Leipzig) directly to the south, with key access points including the Zwickau-Ost and Zwickau-West exits on the A72.[119][120] These connections facilitate efficient links to major cities like Leipzig, Dresden, and Chemnitz, supporting both freight and passenger traffic in the region's automotive industry hub.[119] The city's rail infrastructure centers on Zwickau Hauptbahnhof, the main station handling regional and local services, with the "Zwickau model" enabling seamless integration of standard-gauge regional trains (1435 mm) and narrow-gauge trams (1000 mm) via a three-rail track system into the city center.[121] This setup, operational since upgrades completed in June 2021, allows direct routes such as RB1 to Kraslice and RB2 to Hof and Cheb without transfers, using modernized signaling for joint operation between the municipal tram operator SVZ and regional provider Vogtlandbahn.[122] The model enhances connectivity to Bavaria and the Czech Republic, with services resuming full-day center access post-refurbishment funded partly by the Verkehrsverbund Mittelsachsen (VMS).[122] Local public transport is managed by Städtische Verkehrsbetriebe Zwickau GmbH (SVZ) in coordination with Regionalverkehr Westsachsen GmbH (RVW) under the VMS framework, comprising a tram network and low-floor bus services that carry an average of 29,000 passengers daily.[123] The system includes 25 dedicated school bus lines for student transport, with trams providing core urban routes integrated with the rail-tram hybrid tracks.[123][124] Air access is limited to Zwickau Airfield (EDBI), a small facility at 1,050 feet elevation supporting light general aviation with a single 6/24 runway, but lacking scheduled commercial flights; major airports like Leipzig/Halle and Dresden serve the region instead.[125]Urban Planning and Environmental Initiatives

Zwickau's urban planning emphasizes integrated development that balances economic growth, housing, mobility, and environmental protection, as coordinated by the city's urban development department. This approach guides the city's spatial evolution, including zoning for residential and industrial areas, with a focus on post-industrial revitalization following the decline of traditional manufacturing. For instance, the reconstruction of the Cainsdorfer Bridge, initiated in phases starting around 2023, incorporates modern infrastructure design to enhance connectivity while prioritizing ecological considerations such as reduced emissions and habitat preservation along the Zwickauer Mulde river.[126][127] Environmental initiatives in Zwickau center on energy transition and climate adaptation, exemplified by the ZED (Zwickauer Energiewende Demonstrator) project, which promotes innovations in urban energy systems to meet Germany's climate targets. Launched to maximize municipal contributions to decarbonization, ZED involves research into efficient heating, renewable integration, and building retrofits, positioning Zwickau as a model for medium-sized cities. Complementing this, the city's Environment and Climate Division enforces policies like a 2025 tree protection ordinance to safeguard urban greenery amid development pressures.[128][129] Sustainable mobility forms a core pillar, with projects like Z-MOVE 2025 developing a digital platform to aggregate data on commuting patterns and promote low-emission transport options for workers, reducing berufsbedingte (work-related) traffic. The "Extended Station Suburb" initiative employs intelligent traffic systems to digitize road management, cutting congestion and pollutants in rail-adjacent areas. Volkswagen's Zwickau plant, a major employer, supports these efforts through its 2017 switch to 100% eco-power and full conversion to electric vehicle production by 2019, which has lowered local industrial emissions significantly.[130][131][132]International Ties

Sister Cities and Partnerships

Zwickau maintains twin town partnerships, known as Städtepartnerschaften, with five cities across Europe and Asia, focusing on cultural exchanges, youth programs, economic cooperation, and mutual support initiatives. These relationships emphasize practical collaborations, such as delegation visits, student exchanges, and joint events, often highlighted in city press releases and tourism profiles.[118] The partnerships are as follows:| Partner City | Country | Established |

|---|---|---|

| Dortmund | Germany | 1988 |

| Jablonec nad Nisou | Czech Republic | 1971 |

| Zaanstad | Netherlands | 1987 |

| Yandu District (Yancheng) | China | 2013 |

| Volodymyr-Volynskyi (referred to as Volodymyr) | Ukraine | 2013 |