Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Taxicab geometry

View on Wikipedia

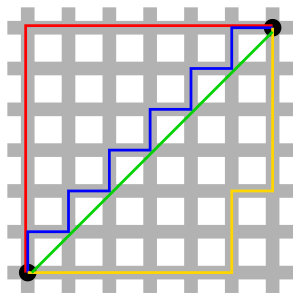

Taxicab geometry or Manhattan geometry is geometry where the familiar Euclidean distance is ignored, and the distance between two points is instead defined to be the sum of the absolute differences of their respective Cartesian coordinates, a distance function (or metric) called the taxicab distance, Manhattan distance, or city block distance. The name refers to the island of Manhattan, or generically any planned city with a rectangular grid of streets, in which a taxicab can only travel along grid directions. In taxicab geometry, the distance between any two points equals the length of their shortest grid path. This different definition of distance also leads to a different definition of the length of a curve, for which a line segment between any two points has the same length as a grid path between those points rather than its Euclidean length.

The taxicab distance is also sometimes known as rectilinear distance or L1 distance (see Lp space).[1] This geometry has been used in regression analysis since the 18th century, and is often referred to as LASSO. Its geometric interpretation dates to non-Euclidean geometry of the 19th century and is due to Hermann Minkowski.

In the two-dimensional real coordinate space , the taxicab distance between two points and is . That is, it is the sum of the absolute values of the differences in both coordinates.

Formal definition

[edit]The taxicab distance, , between two points in an n-dimensional real coordinate space with fixed Cartesian coordinate system, is the sum of the lengths of the projections of the line segment between the points onto the coordinate axes. More formally,For example, in , the taxicab distance between and is

History

[edit]The L1 metric was used in regression analysis, as a measure of goodness of fit, in 1757 by Roger Joseph Boscovich.[2] The interpretation of it as a distance between points in a geometric space dates to the late 19th century and the development of non-Euclidean geometries. Notably it appeared in 1910 in the works of both Frigyes Riesz and Hermann Minkowski. The formalization of Lp spaces, which include taxicab geometry as a special case, is credited to Riesz.[3] In developing the geometry of numbers, Hermann Minkowski established his Minkowski inequality, stating that these spaces define normed vector spaces.[4]

The name taxicab geometry was introduced by Karl Menger in a 1952 booklet You Will Like Geometry, accompanying a geometry exhibit intended for the general public at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago.[5]

Properties

[edit]Thought of as an additional structure layered on Euclidean space, taxicab distance depends on the orientation of the coordinate system and is changed by Euclidean rotation of the space, but is unaffected by translation or axis-aligned reflections. Taxicab geometry satisfies all of Hilbert's axioms (a formalization of Euclidean geometry) except that the congruence of angles cannot be defined to precisely match the Euclidean concept, and under plausible definitions of congruent taxicab angles, the side-angle-side axiom is not satisfied as in general triangles with two taxicab-congruent sides and a taxicab-congruent angle between them are not congruent triangles.

Spheres

[edit]

In any metric space, a sphere is a set of points at a fixed distance, the radius, from a specific center point. Whereas a Euclidean sphere is round and rotationally symmetric, under the taxicab distance, the shape of a sphere is a cross-polytope, the n-dimensional generalization of a regular octahedron, whose points satisfy the equation:

where is the center and r is the radius. Points on the unit sphere, a sphere of radius 1 centered at the origin, satisfy the equation

In two dimensional taxicab geometry, the sphere (called a circle) is a square oriented diagonally to the coordinate axes. The image to the right shows in red the set of all points on a square grid with a fixed distance from the blue center. As the grid is made finer, the red points become more numerous, and in the limit tend to a continuous tilted square. Each side has taxicab length 2r, so the circumference is 8r. Thus, in taxicab geometry, the value of the analog of the circle constant π, the ratio of circumference to diameter, is equal to 4.

A closed ball (or closed disk in the 2-dimensional case) is a filled-in sphere, the set of points at distance less than or equal to the radius from a specific center. For cellular automata on a square grid, a taxicab disk is the von Neumann neighborhood of range r of its center.

A circle of radius r for the Chebyshev distance (L∞ metric) on a plane is also a square with side length 2r parallel to the coordinate axes, so planar Chebyshev distance can be viewed as equivalent by rotation and scaling to planar taxicab distance. However, this equivalence between L1 and L∞ metrics does not generalize to higher dimensions.

Whenever each pair in a collection of these circles has a nonempty intersection, there exists an intersection point for the whole collection; therefore, the Manhattan distance forms an injective metric space.

Arc length

[edit]Let be a continuously differentiable function. Let be the taxicab arc length of the graph of on some interval . Take a partition of the interval into equal infinitesimal subintervals, and let be the taxicab length of the subarc. Then[6]

By the mean value theorem, there exists some point between and such that .[7] Then the previous equation can be written

Then is given as the sum of every partition of on as they get arbitrarily small.

To test this, take the taxicab circle of radius centered at the origin. Its curve in the first quadrant is given by whose length is

Multiplying this value by to account for the remaining quadrants gives , which agrees with the circumference of a taxicab circle.[8] Now take the Euclidean circle of radius centered at the origin, which is given by . Its arc length in the first quadrant is given by

Accounting for the remaining quadrants gives again. Therefore, the circumference of the taxicab circle and the Euclidean circle in the taxicab metric are equal.[9] In fact, for any function that is monotonic and differentiable with a continuous derivative over an interval , the arc length of over is .[10]

Triangle congruence

[edit]

Two triangles are congruent if and only if three corresponding sides are equal in distance and three corresponding angles are equal in measure. There are several theorems that guarantee triangle congruence in Euclidean geometry, namely Angle-Angle-Side (AAS), Angle-Side-Angle (ASA), Side-Angle-Side (SAS), and Side-Side-Side (SSS). In taxicab geometry, however, only SASAS guarantees triangle congruence.[11]

Take, for example, two right isosceles taxicab triangles whose angles measure 45-90-45. The two legs of both triangles have a taxicab length 2, but the hypotenuses are not congruent. This counterexample eliminates AAS, ASA, and SAS. It also eliminates AASS, AAAS, and even ASASA. Having three congruent angles and two sides does not guarantee triangle congruence in taxicab geometry. Therefore, the only triangle congruence theorem in taxicab geometry is SASAS, where all three corresponding sides must be congruent and at least two corresponding angles must be congruent.[12] This result is mainly due to the fact that the length of a line segment depends on its orientation in taxicab geometry.

Applications

[edit]Compressed sensing

[edit]In solving an underdetermined system of linear equations, the regularization term for the parameter vector is expressed in terms of the norm (taxicab geometry) of the vector.[13] This approach appears in the signal recovery framework called compressed sensing.

Differences of frequency distributions

[edit]Taxicab geometry can be used to assess the differences in discrete frequency distributions. For example, in RNA splicing positional distributions of hexamers, which plot the probability of each hexamer appearing at each given nucleotide near a splice site, can be compared with L1-distance. Each position distribution can be represented as a vector where each entry represents the likelihood of the hexamer starting at a certain nucleotide. A large L1-distance between the two vectors indicates a significant difference in the nature of the distributions while a small distance denotes similarly shaped distributions. This is equivalent to measuring the area between the two distribution curves because the area of each segment is the absolute difference between the two curves' likelihoods at that point. When summed together for all segments, it provides the same measure as L1-distance.[14]

See also

[edit]

- Chebyshev distance

- Hamming distance – The number of differing bits between two strings of binary digits

- Lee distance

- Orthogonal convex hull – Minimal superset that intersects each axis-parallel line in an interval

- Staircase paradox – The paradox that the limit of the lengths of finer and finer "staircase curves" does not tend to the length of the diagonal line segment the curves tend towards

References

[edit]- ^ Black, Paul E. "Manhattan distance". Dictionary of Algorithms and Data Structures. Retrieved October 6, 2019.

- ^ Stigler, Stephen M. (1986). The History of Statistics: The Measurement of Uncertainty before 1900. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674403406. Retrieved October 6, 2019.

- ^ Riesz, Frigyes (1910). "Untersuchungen über Systeme integrierbarer Funktionen". Mathematische Annalen (in German). 69 (4): 449–497. doi:10.1007/BF01457637. hdl:10338.dmlcz/128558. S2CID 120242933.

- ^ Minkowski, Hermann (1910). Geometrie der Zahlen (in German). Leipzig and Berlin: R. G. Teubner. JFM 41.0239.03. MR 0249269. Retrieved October 6, 2019.

- ^ Menger, Karl (1952). You Will Like Geometry. A Guide Book for the Illinois Institute of Technology Geometry Exhibition. Chicago: Museum of Science and Industry. Golland, Louise (1990). "Karl Menger and Taxicab Geometry". Mathematics Magazine. 63 (5): 326–327. doi:10.1080/0025570x.1990.11977548.

- ^ Heinbockel, J.H. (2012). Introduction to Calculus Volume II. Old Dominion University. pp. 54–55.

- ^ Penot, J.P. (1988-01-01). "On the mean value theorem". Optimization. 19 (2): 147–156. doi:10.1080/02331938808843330. ISSN 0233-1934.

- ^ Petrović, Maja; Malešević, Branko; Banjac, Bojan; Obradović, Ratko (2014). Geometry of some taxicab curves. 4th International Scientific Conference on Geometry and Graphics. Serbian Society for Geometry and Graphics, University of Niš, Srbija. arXiv:1405.7579.

- ^ Kemp, Aubrey (2018). Generalizing and Transferring Mathematical Definitions from Euclidean to Taxicab Geometry (PhD thesis). Georgia State University. doi:10.57709/12521263.

- ^ Thompson, Kevin P. (2011). "The Nature of Length, Area, and Volume in Taxicab Geometry". International Electronic Journal of Geometry. 4 (2): 193–207. arXiv:1101.2922.

- ^ Mironychev, Alexander (2018). "SAS and SSA Conditions for Congruent Triangles". Journal of Mathematics and System Science. 8 (2): 59–66.

- ^ THOMPSON, KEVIN; DRAY, TEVIAN (2000). "Taxicab Angles and Trigonometry". Pi Mu Epsilon Journal. 11 (2): 87–96. ISSN 0031-952X. JSTOR 24340535.

- ^ Donoho, David L. (March 23, 2006). "For most large underdetermined systems of linear equations the minimal -norm solution is also the sparsest solution". Communications on Pure and Applied Mathematics. 59 (6): 797–829. doi:10.1002/cpa.20132. S2CID 8510060.

- ^ Lim, Kian Huat; Ferraris, Luciana; Filloux, Madeleine E.; Raphael, Benjamin J.; Fairbrother, William G. (July 5, 2011). "Using positional distribution to identify splicing elements and predict pre-mRNA processing defects in human genes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (27): 11093–11098. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10811093H. doi:10.1073/pnas.1101135108. PMC 3131313. PMID 21685335.

Further reading

[edit]- Gardner, Martin (1997). "10. Taxicab Geometry". The Last Recreations. Copernicus. pp. 159–176. ISBN 0-387-94929-1.

- Krause, Eugene F. (1975). Taxicab Geometry. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0201039346. Reprinted by Dover (1986), ISBN 0-486-25202-7.

- Strogatz, Steven (2025-06-09). "Taxicab Geometry". The New York Times.

External links

[edit]- Weisstein, Eric W. "Taxicab Metric". MathWorld.

- Malkevitch, Joe (October 1, 2007). "Taxi!". American Mathematical Society. Retrieved October 6, 2019.

- Taxicab metric with stoplights

Taxicab geometry

View on GrokipediaDefinition

Metric Axioms

Taxicab geometry, also known as Manhattan geometry, is the real plane (or more generally ) equipped with the metric, defined by the distance functionThis distance measures the total horizontal and vertical displacement between points, analogous to navigating a grid-like city street system.[7][8] The metric induces the norm on vectors in , given by for , where the distance between points and is . This norm satisfies the standard norm axioms: positivity (, with equality if and only if ), homogeneity ( for scalar ), and the triangle inequality ().[9][10] To confirm that the metric defines a valid metric space, it must satisfy the following axioms for all points :

-

Non-negativity and identity of indiscernibles: , with if and only if .

Since absolute values are non-negative, their sum is non-negative. Equality holds only if both and , implying .[7][8] -

Symmetry: .

This follows directly from the symmetry of the absolute value function, as for any real numbers , applied componentwise.[7][8] -

Triangle inequality: .

By the subadditivity of the absolute value (i.e., for real ), we have

and similarly for the -coordinates. Adding these inequalities yields

This completes the verification.[7][11][8]

![{\displaystyle [a,b]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9c4b788fc5c637e26ee98b45f89a5c08c85f7935)