Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Aesculapian snake

View on Wikipedia

| Aesculapian snake | |

|---|---|

| |

| Adult Zamenis longissimus from the region of Ticino, Switzerland | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Serpentes |

| Family: | Colubridae |

| Genus: | Zamenis |

| Species: | Z. longissimus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Zamenis longissimus (Laurenti, 1768)

| |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

The Aesculapian snake /ˌɛskjəˈleɪpiən/ (Zamenis longissimus, previously Elaphe longissima) is a species of non-venomous constrictor snake native to Europe, a member of the subfamily Colubrinae of the family Colubridae. Growing up to 2 metres (6.6 ft) in length, it is among the largest European snakes, similar in size to the four-lined snake (Elaphe quatuorlineata) and the Montpellier snake (Malpolon monspessulanus). The Aesculapian snake has been of cultural and historical significance for its role in ancient Greek, Roman, and Illyrian mythology and derived symbolism.

Description

[edit]

Zamenis longissimus hatches at around 30 cm (11.8 in). Adults are usually from 110 cm (43.3 in) to 160 cm (63 in) in total length (tail included), but can grow to 200 cm (79 in), with the record size being 225 cm (7.38 ft).[3] Expected body mass in adult Aesculapian snakes is from 350 to 890 g (0.77 to 1.96 lb).[4][5] It is dark, long, slender, and typically bronzy in colour, with smooth scales that give it a metallic sheen.

Juveniles can easily be confused with juvenile grass snakes (Natrix natrix) and barred grass snakes (Natrix helvetica), because juvenile Aesculapians also have a yellow collar on the neck that may persist for some time in younger adults. Juvenile Z. longissimus are light green or brownish-green with various darker patterns along the flanks and on the back. Two darker patches appear in the form of lines running on the top of the flanks. The head in juveniles also features several distinctive dark spots, one hoof-like on the back of the head in-between the yellow neck stripes, and two paired ones, with one horizontal stripe running from the eye and connecting to the neck marks, and one short vertical stripe connecting the eye with the fourth to fifth upper labial scales.

Adults are much more uniform, sometimes being olive-yellow, brownish-green, sometimes almost black. Often in adults, there may be a more or less regular pattern of white-edged dorsal scales appearing as white freckles all over the body up to moiré-like structures in places, enhancing the shiny metallic appearance. Sometimes, especially when pale in colour, two darker longitudinal lines along the flanks can be visible. The belly is plain yellow to off-white, while the round iris has amber to ochre colouration. Melanistic, erythristic, and albinotic natural forms are known, as is a dark grey form.

Although there is no noticeable sexual dimorphism in colouration, males grow significantly longer than females, presumably because of the more significant energy input of the latter into the reproductive cycle. Maximum weight for German populations has been 890 grams (1.96 lb) for males and 550 grams (1.21 lb) for females (Böhme 1993; Gomille 2002). Other distinctions, as in many snakes, include in males a relatively longer tail to total body length and a wider tail base.

Scale arrangement includes 23 dorsal scale rows at midbody (rarely 19 or 21), 211–250 ventral scales, a divided anal scale, and 60–91 paired subcaudal scales (Schultz 1996; Arnold 2002). Ventral scales are sharply angled where the underside meets the side of the body, which enhances the species' climbing ability.

Geographic range

[edit]

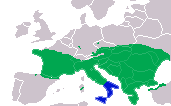

The contiguous area of the previous nominotypical subspecies, Zamenis longissimus longissimus, which is now the only recognized monotypic form, covers most of France except in the north (up to about the latitude of Paris), the Spanish Pyrenees and the eastern side of the Spanish northern coast, Italy (except the south and Sicily), all of the Balkan peninsula down to Greece and Asia Minor and parts of Central and Eastern Europe up until about the 49th parallel in the eastern part of the range (Switzerland, Austria, South Moravia (Podyjí/Thayatal in Austria) in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovakia, south Poland (mainly Bieszczady/Bukovec Mountains in Slovakia), Romania, south-west Ukraine).

Further isolated populations have been identified in western Germany (Schlangenbad, Odenwald, lower Salzach, plus one - near Passau - connected to the contiguous distribution area) and the northwest of the Czech Republic (near Karlovy Vary, the northernmost known current natural presence of the species).[6] Also found in a separate enclave south of Greater Caucasus along the Russian, Georgian and Turkish northeastern and eastern shores of the Black Sea.

Two further enclaves include the first around Lake Urmia in northern Iran, and on the northern slopes of Mount Ararat in east Turkey, roughly halfway between the former and the Black Sea habitats.[3] V.L. Laughlin hypothesized that parts of the species' geographical distribution may be the result of intentional placement and later release of these snakes by Romans from the temples of Asclepius, classical god of medicine, where they were important in the medical rituals and worship of the god.[8][9]

The previously recognised subspecies Zamenis longissimus romanus, found in southern Italy and Sicily, has been recently elevated to the status of a separate new species, Zamenis lineatus (Italian Aesculapian snake). It is lighter in color, with a reddish-orange to glowing red iris.

The populations previously classified as Elaphe longissima living in south-east Azerbaijan and northern Iranian Hyrcanian forests were reclassified by Nilson and Andrén in 1984 to Elaphe persica, now Zamenis persicus.

According to fossil evidence, the species' area in the warmer Atlantic period (around 8000–5000 years ago) of Holocene reached as far north as Denmark. Three specimens were collected in Denmark between 1810 and 1863 on the southern part of Zealand, presumably from a relict and now extinct population.[10] The current northwestern Czech population now is considered an autochthonous remnant of that maximum distribution based on the results of genetic analyses (it is closest genetically to the Carpathian populations). This likely applies also to the German populations. There are also fossils showing that they had UK residency during earlier interglacial periods but were driven south afterwards with subsequent glacials; these repeated climate-caused contractions and extensions of range in Europe appear to have occurred multiple times over the Pleistocene.[11]

Escaped populations in Great Britain

[edit]There are three populations of Aesculapian snake, descendants of escapees, in Great Britain. The oldest recorded of these is on the grounds and in the vicinity of the Welsh Mountain Zoo, near Colwyn Bay, North Wales. This population has survived and consistently reproduced since at least the early 1970s,[12] and, in 2022, the population was estimated at 70 adults.[13]

A second, more recently established population was reported in 2010 along Regent's Canal, near the London Zoo, likely living on rats and mice, and thought to number a few dozen. Growth of this population may be limited due to the urban setting and potential scarcity of appropriate nesting sites. It is thought this colony has been present for years, living unseen: it is not harmful or invasive and is predicted to die out.[14] Sightings were still being reported in 2023, with the population estimated at around 40.[15]

In 2020, a third population was confirmed in Britain, this one in Bridgend, Wales. This group has thrived for approximately 20 years.[16]

As of 2022, the Aesculapian snake is believed to be the only non-native species of snake in the United Kingdom to have established breeding populations.[17]

Habitat

[edit]

The Aesculapian snake prefers forested, warm but not hot, moderately humid but not wet, hilly or rocky habitats with proper insolation and varied, not sparse vegetation that provides sufficient variation in local microclimates, helping the reptile with thermoregulation. In most of its range it is typically found in relatively intact or fairly cultivated warmer temperate broadleaf forests including the more humid variety such as along river valleys and riverbeds (but not marshes) and forest steppes. Frequented locations include places such as forest clearings in succession, shrublands at the edges of forests and forest/field ecotones, woods interspersed with meadows etc. However, it generally does not avoid human presence, being often found in places such as gardens and sheds, and even prefers habitats such as old walls and stonewalls, derelict buildings and ruins that offer a variety of hiding and basking places. The synanthropic aspect appears to be more pronounced in northernmost parts of the range where it is dependent on human structures for food, warmth and hatching grounds. It avoids open plains and agricultural deserts.

In the south its range seems to coincide with the borderline between deciduous broadleaf forests and Mediterranean shrublands, with the latter presumably too dry for the species. In the north its line of presence appears temperature-limited.[3][7]

Diet and predators

[edit]

The main food source of Zamenis longissimus is small mammals such as shrews, moles, and rodents up to the size of rats. A 130 cm (51 in) adult specimen has been reported to have overpowered a 200 g (7.1 oz) rat. It also eats birds as well as bird eggs and nestlings. It suffocates its prey by constriction, though harmless smaller mouthfuls may be eaten alive without constriction, or simply crushed on eating by jaws. Juveniles mainly eat lizards and arthropods, later small rodents. Other snakes and lizards are taken, but adults are rarely taken.

Predators include badgers and other mustelids, foxes, wild boar (mainly by digging up and eating egg clutches and hatchlings), hedgehogs, and various birds of prey (though there are reports of adults successfully standing their ground). Juveniles may be eaten by smooth snakes and other reptilivorous snakes. Domestic animals such as cats, dogs, and chickens are a threat mainly to juveniles and hatchlings; rats may be dangerous to inactive adults in hibernation. In areas of concurrent distribution, the snake is also preyed upon by introduced North American raccoons and east Asian raccoon dogs.[3][6][7][18]

Behaviour

[edit]Zamenis longissimus is active by day (diurnal). In the warmer months of the year, it comes out in late afternoon or early morning. It is a very good climber capable of ascending even vertical, branchless tree trunks. It has been observed at heights of 4 to 5 m (13 to 16 ft) and even 15 to 20 m (49 to 66 ft) in trees, and foraging in the roofs of buildings. Observed optimum temperature for activity in German populations is 20–22 °C (68–72 °F) (Heems 1988) and it is rarely recorded below 16 °C (61 °F) or above 25 °C (77 °F), other observations for Ukrainian populations (Skarbek et Ščerban 1980) put minimum activity temperature from 19 °C (66 °F) and optimum to 21–26 °C (70–79 °F). Above around 27 °C (81 °F) it tries to avoid exposure to direct sunlight and ceases activity with more extreme heat. It will exhibit a degree of activity even during hibernation, moving around to keep a body temperature near 5 °C (41 °F) and occasionally emerging to bask on sunny days.

The average home range for French populations has been calculated at 1.14 ha (2.8 acres), however males will travel longer distances of up to 2 km (1.2 mi) to find females during the mating season and females to find suitable hatching sites to lay eggs.

The Aesculapian snake is deemed secretive and not always easy to find even in areas of positive presence, or found in surprising contexts.[3][6][7][18] In contact with humans, it can be rather tame, possibly due to its cryptic coloration keeping it hidden within its natural environment. It usually disappears and hides, but if cornered it may sometimes stand its ground and try to intimidate its opponent, sometimes with a chewing-like movement of the mouth and occasionally biting.[6]

It has been speculated that the species may be more prevalent than thought due to spending a significant part of its time in tree canopy, but no reliable data exist as to what part that would be. In France it is said to be the only snake species that occurs inside dense, shadowy forests with minimum undergrowth, presumably because of using foliage for basking and foraging. In other parts of its geographic range it has been reported to only use the canopy on a more substantial basis in largely uninhabited areas, such as the natural beech forests of the East Slovak and Ukrainian Carpathians, with similar characteristics.[3][7]

Reproduction

[edit]Minimum length of individuals of Zamenis longissimus entering the reproductive cycle has been reported at 85–100 cm (33–39 in), which corresponds to sexual maturity age of about 4–6 years. Breeding occurs annually after hibernation in spring, typically from mid-May to mid-June. In this time the snakes actively seek each other and mating begins. Rival males engage in ritual fights the aim of which is to pin down the opponent's head with one's own or coils of one's body; biting may occur but is not typical. The actual courtship takes the form of an elegant dance between the male and female, with anterior portions of the bodies raised in an S-shape and the tails entwined. The male may also grasp the female's head with its jaws (Lotze 1975). 4 to 6 weeks after mating, about 10 eggs are laid (extremes are from 2 to 20, with 5–11 on average) in a moist, warm spot where organic decomposition occurs, usually under hay piles, in rotting wood piles, heaps of manure or leaf mold, old tree stumps and similar places. Particularly in the northern parts of the range, preferred hatching grounds often are used by multiple females and are also shared with grass snakes. The eggs incubate for around 8 (6 to 10) weeks before hatching.[3][6]

Taxonomy

[edit]Apart from recent taxonomic changes, there are currently four recognised phylogeographically traceable genetic lines in the species Zamenis longissimus: the Western haplotype, the Adriatic haplotype, the Danube haplotype, and the Eastern haplotype.

The status of the Iranian enclave population remains unclear due to its specific morphological characteristics (smaller length, different scale arrangement, darker underbelly), probably pending reclassification.[18]

History

[edit]

The Aesculapian snake was first described by Josephus Nicolaus Laurenti in 1768 as Natrix longissima, later it was also known as Coluber longissimus and for the most part of its history as Elaphe longissima. The current scientific name of the species based on revisions of the large genus Elaphe is Zamenis longissimus. Zamenis is from Greek ζαμενής[19] "angry", "irritable", "fierce", longissimus comes from Latin and means "longest"; the snake is one of the longest over its range. The common name of the species, Aesculape in French and its equivalent in other languages, refers to the classical god of healing (Greek Asclepius and later Roman Aesculapius) whose temples the snake was encouraged around. It is surmised that the typical depiction of the god with his snake-entwined staff features the species. Later from these, modern symbols developed of the medical professions as used in a number of variations today. The species, along with four-lined snakes, is carried in an annual religious procession in Cocullo in central Italy, which is of separate origin and was later made part of the Catholic calendar.

-

The classical Rod of Aesculapius as a symbol of human medicine

-

The V-form as a symbol of veterinary medicine

-

The Aesculapian snake with the Bowl of Hygieia as a symbol of pharmacology

Conservation

[edit]Though the Aesculapian snake occupies a relatively broad range and is not endangered as a species, it is thought to be in general decline largely due to anthropic disturbances. The snake is especially vulnerable in fringe parts and northern areas of its distribution where, given the historic retreat as a result of climatic changes since the Holocene climatic optimum, local populations remain isolated both from each other and from the main distribution centers, with no exchange of genetic material and no reinforcement through migration as a result. In such areas active local protection is due. [citation needed]

The snake has been classified as Critically Endangered in the German Red List of endangered species.[citation needed] In most other countries including France, Switzerland, Austria, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Bulgaria, Poland, Ukraine and Russia it is also under protection status.[citation needed]

Among the key concerns is human-caused habitat destruction, with a series of respective recommendations concerning forestry and agriculture as to the protection through non-intervention of the species' core distribution centers, including targeted protection of potential hatching and hibernation places like old growth zones and fringe ecotones near woodland areas.[citation needed]

A significant threat also are roads both in terms of new construction and rising traffic, with a risk of further fragmentation of populations and loss of genetic exchange.[3]

Gallery

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Agasyan, A.; Avci, A.; Tuniyev, B.; Crnobrnja Isailović, J.; Lymberakis, P.; Andrén, C.; Cogălniceanu, D.; Wilkinson, J.; Ananjeva, N.B.; Üzüm, N.; Orlov, N.L.; Podloucky, R.; Tuniyev, S.; Kaya, U.; Böhme, W.; Ajtic, R.; Vogrin, M.; Corti, C.; Pérez Mellado, V.; Sá-Sousa, P.; Cheylan, M.; Pleguezuelos, J.M.; Borczyk, B.; Schmidt, B.R.; Meyer, A. (2017). "Zamenis longissimus ". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017 e.T157266A49063773. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-2.RLTS.T157266A49063773.en. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ^ Species Zamenis longissimus at The Reptile Database www.reptile-database.org.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Edgar P, Bird DR (2006). "Action Plan for the Conservation of the Aesculapian Snake (Zamenis longissimus) in Europe". Strasbourg: Council of Europe: Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats. Standing Committee, 26th meeting, 27–30 November 2006.

- ^ Kovar, Roman; Brabec, Marek; Vita, Radovan; Bocek, Radomir (March 2014). "Mortality Rate and Activity Patterns of an Aesculapian Snake (Zamenis longissimus) Population Divided by a Busy Road". Journal of Herpetology. 48 (1): 24–33. doi:10.1670/12-090. S2CID 83562512.

- ^ Kreiner, Guido (2007). The Snakes of Europe: All Species from West of the Caucasus Mountains. Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Edition Chimaira. ISBN 978-3-89973-475-1.[page needed]

- ^ a b c d e f "Aesculapian snake, Zamenis longissimus at Reptiles & Amphibiens de France". Archived from the original on 11 July 2017. Retrieved 2 July 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Musilová R (2011). "Ekologie a status užovky stromové (Zamenis longissimus) v severozápadních Čechách [Ecology and Status of the Aesculapian Snake (Zamenis longissimus) in northwest Bohemia]" (in Czech and English). Dissertation. Prague: Czech University of Life Sciences Prague. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- ^ Laughlin, VC (July 1962). "The Aesculapian staff and the caduceus as medical symbols". The Journal of the International College of Surgeons. 38: 82–92. PMID 14462759.

- ^ Schmidt, Karl Patterson; Inger, Robert F. (1957). Living Reptiles of the World. New York: Hanover House. p. 211. ISBN 978-0-385-01726-8.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Hvass, Hans (1970). Danmarks Dyreverden, vol 5. Copenhagen: Rosenkilde og Bakker. pp. 223–228. OCLC 15637083.

- ^ Musilová, Radka; Zavadil, Vít; Marková, Silvia; Kotlík, Petr (December 2010). "Relics of the Europe's warm past: Phylogeography of the Aesculapian snake". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 57 (3): 1245–1252. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2010.09.017. PMID 20883801.

- ^ Press Office (16 May 2006). "Wild snake caught on film in north Wales". BBC.

- ^ "Rat-eating snakes in Wales after 10,000 years out of UK". BBC News. 13 May 2022. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ Loeb, Josh (2 September 2010). ""The Camden Creature" – An amphibian and reptile trust says our waterways are alive with some exotic creatures". Islington Tribune. Archived from the original on 12 February 2015.

- ^ Wiggins, Dan (6 May 2023). "The London canal where 2m long exotic snakes keep terrifying unwitting walkers". MyLondon.

- ^ Clemens, David J. (Summer 2020). "First record of the aesculapian snake (Zamenis longissimus) in South Wales". Herpetological Bulletin (152): 30–31. doi:10.33256/152.3031.

- ^ "Snakes of the British Isles: how many are native, which are venomous, and how to identify". www.discoverwildlife.com. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ a b c Baruš V, Král B, Oliva O, Opatrný E, Rehák I, Roček Z, Roth P, Špinar Z, Vojtková L (1992). Plazi–Reptilia. Fauna ČSFR, volume 26 (in Czech). Academia. ISBN 978-80-200-0082-8. OCLC 165544998.[page needed]

- ^ Wagler, J. (1830). Natürliches System der Amphibien : mit vorangehender Classification der Säugethiere und Vögel : ein Beitrag zur vergleichenden Zoologie. (Zamenis, new genus, p. 188). (in German and Latin). Available online at the Biodiversity Heritage Library (BHL).

- This page uses translations from respective articles in German, French, Russian and Polish Wikipedias.

Further reading

[edit]- Arnold EN, Burton JA (1978). A Field Guide to the Reptiles and Amphibians of Britain and Europe. London: Collins. 272 pp. + Plates 1–40. ISBN 0-00-219318-3. (Elaphe longissima, pp. 199–200 + Plate 36 + Map 112 on p. 266).

- Boulenger GA (1894). Catalogue of the Snakes in the British Museum (Natural History). Volume II., Containing the Conclusion of the Colubridæ Aglyphæ. London: Trustees of the British Museum (Natural History). (Taylor and Francis, printers). xi + 382 pp. + Plates I–XX. (Coluber longissimus, pp. 52–54).

- Laurenti JN (1768). Specimen medicum, exhibens synopsin reptilium emendatam cum experimentis circa venena et antidota reptilium austricorum. Vienna: "Joan. Thom. Nob. de Trattnern". 214 pp. + Plates I–V. (Natrix longissima, new species, p. 74). (in Latin).