Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Fire temple

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Zoroastrianism |

|---|

|

|

|

A fire temple (Persian: آتشکده, romanized: ātashkade; Gujarati: અગિયારી, romanized: agiyārī)[a] is a place of worship for Zoroastrians.[1][2][3] In Zoroastrian doctrine, atar and aban (fire and water) are agents of ritual purity.

Clean, white "ash for the purification ceremonies [is] regarded as the basis of ritual life", which "are essentially the rites proper to the tending of a domestic fire, for the temple [fire] is that of the hearth fire raised to a new solemnity".[4] For, one "who sacrifices unto fire with fuel in his hand ..., is given happiness".[5]

As of 2021[update], there were 167 fire temples in the world, of which 45 were in Mumbai, 105 in the rest of India, and 17 in other countries.[6][7] Of these, only nine (one in Iran and eight in India) are the main temples known as Atash Behrams; the remainder are the smaller temples known as agiaries.

History and development

[edit]Concept

[edit]

First evident in the 9th century BCE, the rituals of fire are contemporary with that of Zoroastrianism itself. It appears at approximately the same time as the shrine cult and is roughly contemporaneous with the introduction of Atar as a divinity. There is no allusion to a temple of fire in the Avesta proper, nor is there any Old Persian word for one.

That the rituals of fire was a doctrinal modification and absent from early Zoroastrianism is also evident in the later Atash Nyash. In the oldest passages of that liturgy, it is the hearth fire that speaks to "all those for whom it cooks the evening and morning meal", which Boyce observes is not consistent with sanctified fire. The temple is an even later development: from Herodotus it is known that in the mid-5th century BCE the Zoroastrians worshipped to the open sky, ascending mounds to light their fires.[8] Strabo confirms this, noting that in the 6th century, the sanctuary at Zela in Cappadocia was an artificial mound, walled in, but open to the sky, although there is no evidence whatsoever that the Zela-sanctuary was Zoroastrian.[9] Although the "burning of fire" was a key element in Zoroastrian worship, the burning of "eternal" fire, as well as the presence of "light" in worship, was also a key element in many other religions.

By the Parthian Empire (250 BCE – 226 CE), there were two places of worship in Zoroastrianism: one, called bagin or ayazan, was a sanctuary dedicated to a specific divinity; it was constructed in honor of the patron saint (or angel) of an individual or family and included an icon or effigy of the honored. The second, the atroshan, were the "places of burning fire" which became more and more prevalent as the iconoclastic movement gained support. Following the rise of the Sassanid dynasty, the shrines to the Yazatas continued to exist, but with the statues – by law – either abandoned or replaced by fire altars.

Also, as Schippman observed,[10] there is no evidence even during the Sassanid era (226–650 CE) that the fires were categorized according to their sanctity. "It seems probable that there were virtually only two, namely the Atash-i Vahram [literally: "victorious fire", later misunderstood to be the Fire of Bahram],[11] and the lesser Atash-i Adaran, or 'Fire of Fires', a parish fire, as it were, serving a village or town quarter".[10][12] Apparently, it was only in the Atash-i Vahram that fire was kept continuously burning, with the Adaran fires being annually relit. While the fires themselves had special names, the structures did not, and it has been suggested that "the prosaic nature of the middle Persian names (kadag, man, and xanag are all words for an ordinary house) perhaps reflect a desire on the part of those who fostered the temple-cult ... to keep it as close as possible in character to the age-old cult of the hearth-fire, and to discourage elaboration".[13] Sasanian coins always depicted a fire altar with flames on the reverse.[14]

The Battle of al-Qādisiyyah (636 CE) and the Battle of Nihavānd (642 CE) were instrumental to the collapse of the Sassanid Empire and state-sponsored Zoroastrianism; destruction or conversion (mosques) of some fire temples in Greater Iran followed. The faith was practiced largely by the aristocracy but large numbers of fire temples did not exist. Some fire temples continued with their original purpose although many Zoroastrians fled. Legend says that some took fire with them and it most probably served as a reminder of their faith in an increasingly persecuted community since fire originating from a temple was not a tenet of the religious practice.[citation needed]

Archaeological traces

[edit]

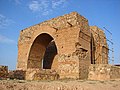

The oldest remains of what has been identified as a fire temple are those on Mount Khajeh, near Lake Hamun in Sistan. Only traces of the foundation and ground-plan survive and have been tentatively dated to the 3rd or 4th century BCE. The temple was rebuilt during the Parthian era (250 BCE – 226 CE), and enlarged during Sassanid times (226–650 CE).

The characteristic feature of the Sassanid fire temple was its domed sanctuary where the fire-altar stood.[16] This sanctuary always had a square ground plan with a pillar in each corner that then supported the dome (the gombad). Archaeological remains and literary evidence from Zend commentaries on the Avesta suggest that the sanctuary was surrounded by a passageway on all four sides. "On a number of sites the gombad, made usually of rubble masonry with courses of stone, is all that survives, and so such ruins are popularly called in Fars čahār-tāq or 'four arches'."[17]

Ruins of temples of the Sassanid era have been found in various parts of the former empire, mostly in the southwest (Fars, Kerman and Elam), but the biggest are those of Adur Gushnasp in Media Minor (see also The Great Fires, below). Many more ruins are popularly identified as the remains of Zoroastrian fire temples even when their purpose is of evidently secular nature, or are the remains of a temple of the shrine cults, or as is the case of a fort-like fire temple and monastery at Surkhany, Azerbaijan, that unambiguously belongs to another religion. The remains of a fire-altar, most likely constructed during the proselytizing campaign of Yazdegerd II (r. 438–457) against the Christian Armenians, have been found directly beneath the main altar of the Echmiadzin Cathedral, the Mother See of the Armenian Apostolic Church.[18]

Legendary Great Fires

[edit]Apart from relatively minor fire temples, three were said to derive directly from Ahura Mazda, thus making them the most important in Zoroastrian tradition. These were the "Great Fires" or "Royal Fires" of Adur Burzen-Mihr, Adur Farnbag, and Adur Gushnasp. The legends of the Great Fires are probably of antiquity (see also Denkard citation, below), for by the 3rd century CE, miracles were said to happen at the sites, and the fires were popularly associated with other legends such as those of the folktale heroes Fereydun, Jamshid and Rustam.

The Bundahishn, an encyclopaedic collection of Zoroastrian cosmogony and cosmology written in Book Pahlavi,[19] which was finished in the 11th or 12th century CE, states that the Great Fires had existed since creation and had been brought forth on the back of the ox Srishok to propagate the faith, dispel doubt, and protect all humankind. Other texts observe that the Great Fires were also vehicles of propaganda and symbols of imperial sovereignty.

The priests of these respective "Royal Fires" are said to have competed with each other to draw pilgrims by promoting the legends and miracles that were purported to have occurred at their respective sites. Each of the three is also said to have mirrored social and feudal divisions: "The fire which is Farnbag has made its place among the priests; ... the fire which is Gūshnasp has made its place among the warriors; ... the fire which is Būrzīn-Mitrō has made its place among agriculturists" (Denkard, 6.293). These divisions are archaeologically and sociologically revealing, because they make clear that, since from at least the 1st century BCE onwards, society was divided into four, not three, feudal estates.

The Farnbag fire (translated as 'the fire Glory-Given' by Darmesteter) was considered the most venerated of the three because it was seen as the earthly representative of the Atar Spenishta, 'Holiest Fire' of Yasna 17.11, and it is described in a Zend commentary on that verse as "the one burning in Paradise in the presence of Ohrmazd."

Although "in the eyes of [contemporary] Iranian Zoroastrian priests, the three fires were not 'really existing' temple fires and rather belonged to the mythological realm",[20] several attempts have been made to identify the locations of the Great Fires. In the early 20th century, A. V. Jackson identified the remains at Takht-i-Suleiman, midway between Urumieh and Hamadan, as the temple of Adur Gushnasp. The location of the Mithra fire, i.e. that of Burzen-Mihr, Jackson "identified with reasonable certainty" as being near the village of Mihr half-way between Miandasht and Sabzevar on the Khorasan road to Nishapur.[21] The Indian (lesser) Bundahishn records the Farnbag fire having been "on the glory-having mountain which is in Khwarezm" but later moved "upon the shining mountain in the district of Kavul just as it there even now remains" (IBd 17.6). That the temple once stood in Khwarezm is also supported by the Greater (Iranian) Bundahishn and by the texts of Zadsparam (11.9). However, according to the Greater Bundahishn, it was moved "upon the shining mountain of Kavarvand in the Kar district" (the rest of the passage is identical to the Indian edition). Darmesteter identified this "celebrated for its sacred fire which has been transported there from Khvarazm as reported by Masudi" .[21] If this identification is correct, the temple of the Farnbag fire then lay 10 miles southwest of Juwun, midway between Jahrom and Lar. (28°1′N 53°1′E / 28.017°N 53.017°E)

Iranshah Atash Behram

[edit]

According to Parsi legend, when (over a thousand years ago) one group of refugees from (greater) Khorasan landed in Western Gujarat, they had the ash of such a fire with them. This ash, it is said, served as the bed for the fire today at Udvada.[22]

This fire temple was not always at Udvada. According to the Qissa-i Sanjan, 'Story of Sanjan', the only existing account of the early years of Zoroastrian refugees in India and composed at least six centuries after their arrival, the immigrants established a Atash-Warharan, 'victorious fire' (see Warharan for etymology) at Sanjan. Under threat of war (probably in 1465), the fire was moved to the Bahrot Caves 20 km south of Sanjan, where it stayed for 12 years. From there, it was moved to Bansdah, where it stayed for another 14 years before being moved yet again to Navsari, where it would remain until the 18th century. It was then moved to Udvada where it burns today.

Although there are numerous eternally burning Zoroastrian fires today, with the exception of the 'Fire of Warharan', none of them are more than 250 years old. The legend that the Indian Zoroastrians invented the afrinagan (the metal urn in which a sacred fire today resides) when they moved the fire from Sanjan to the Bahrot Caves is unsustainable. Greek historians of the Parthian period reported the use of a metal vase-like urn to transport fire. Sassanid coins of the 3rd-4th century CE likewise reveal a fire in a vase-like container identical in design to the present-day afrinagans. The Indian Zoroastrians do however export these and other utensils to their co-religionists the world over.

Today

[edit]Nomenclature

[edit]One of the more common technical terms – in use – for a Zoroastrian fire temple is dar be-mehr, romanized as darb-e mehr or dialectally slurred as dar-e mehr. The etymology of this term, meaning 'Mithra's Gate' or 'Mithra's Court' is problematic. It has been proposed that the term is a throwback to the age of the shrine cults, the name being retained because all major Zoroastrian rituals were solemnized between sunrise and noon, the time of day especially under Mithra's protection. Etymological theories see a derivation from mithryana (so Meillet) or *mithradana (Gershevitch) or mithraion (Wilcken). It is moreover not clear whether the term referred to a consecrated inner sanctum or to the ritual precinct.[23]

Among present-day Iranian Zoroastrians, the term darb-e mehr includes the entire ritual precinct. It is significantly more common than the older atashkada, a Classical Persian language term that together with its middle Persian predecessors (𐭪𐭲𐭪 𐭠𐭲𐭧𐭱 ātaxš-kadag, -man and -xanag) literally means 'house of fire'. The older terms have the advantage that they are readily understood even by non-Zoroastrian Iranians. In the early 20th century, the Bombay Fasilis (see Zoroastrian calendar) revived the term as the name of their first fire temple, and later in that century the Zoroastrians of Tehran revived it for the name of their principal fire temple.

The term darb-e mehr is also common in India, albeit with a slightly different meaning. Until the 17th century the fire (now) at Udvada was the only continuously burning one on the Indian subcontinent. Each of the other settlements had a small building in which rituals were performed, and the fire of which the priests would relight whenever necessary from the embers carried from their own hearth fires.[3] The Parsis called such an unconsecrated building either dar-be mehr or agiary. The latter is the Gujarati language word for 'house of fire'[3] and thus a literal translation of atashkada. In recent years, the term dar-be mehr has come to refer to a secondary sacred fire (the dadgah) for daily ritual use that is present at the more prestigious fire temples. Overseas, in particular in North America, Zoroastrians use the term dar-be mehr for both temples that have an eternally burning fire as well as for sites where the fire is only kindled occasionally. This is largely due to the financial support of such places by one Arbab Rustam Guiv, who preferred the dialectal Iranian form.

Classification

[edit]Functionally, the fire temples are built to serve the fire within them, and the fire temples are classified (and named) according to the grade of fire housed within them. There are three grades of fires, the Atash Dadgah, Atash Adaran, and Atash Behram.

Atash Dadgah

[edit]The Atash Dadgah is the lowest grade of sacred fire, and can be consecrated within the course of a few hours by two priests, who alternatingly recite the 72 verses of the Yasna liturgy. Consecration may occasionally include the recitation of the Vendidad, but this is optional. A lay person may tend the fire when no services are in progress. The term is not necessarily a consecrated fire, and the term is also applied to the hearth fire, or to the oil lamp found in many Zoroastrian homes.

Atash Adaran

[edit]The next highest grade of fire is the Atash Adaran, the "Fire of fires". It requires a gathering of hearth fire from representatives of the four professional groups (that reflect feudal estates): from a hearth fire of the asronih (the priesthood), the (r)atheshtarih (soldiers and civil servants), the vastaryoshih (farmers and herdsmen) and the hutokshih (artisans and laborers). Eight priests are required to consecrate an Adaran fire and the procedure takes between two and three weeks.

Atash Behram

[edit]

The highest grade of fire is the Atash Behram "Fire of victory", and its establishment and consecration is the most elaborate of the three. It involves the gathering of sixteen different "kinds of fire", that is, fires gathered from 16 different sources, including lightning, fire from a pyre, fire from trades where a furnace is operated, and fires from the hearths as is also the case for the Atash Adaran. Each of the fires is then subject to a purification ritual before it joins the others. Thirty-two priests are required for the consecration ceremony, which can take up to a year to complete.

A temple that maintains an Adaran or Behram fire also maintains at least one Dadgah fire. In contrast to the Adaran and Behram fires, the Dadgah fire is the one at which priests then celebrate the rituals of the faith, and which the public addresses to invoke blessings for a specific individual, a family or an event. Veneration of the greater fires is addressed only to the fire itself – that is, following the consecration of such a fire, only the Atash Nyashes, the litany to the fire in Younger Avestan, is ever recited before it.

A list of the nine Atash Behrams:

- Iranshah Atash Behram in Udvada, India. Established 1742.

- Desai Atash Behram in Navsari, India. Established 1765.

- Dadiseth Atash Behram in Mumbai, India. Established 1783.

- Vakil Atash Behram in Surat, India. Established 1823.

- Modi Atash Behram in Surat, India. Established 1823.

- Wadia Atash Behram in Mumbai, India. Established 1830.

- Banaji Atash Behram in Mumbai, India. Established 1845.

- Anjuman Atash Behram in Mumbai, India. Established 1897.

- Yezd Atash Behram in Yazd, Iran. Established 1934.

Physical attributes

[edit]

The outer façade of a Zoroastrian fire temple is almost always intentionally nondescript and free of embellishment. This may reflect ancient tradition (supported by the prosaic nature of the technical terms for a fire temple) that the principal purpose of a fire temple is to house a sacred fire, and not to glorify what is otherwise simply a building.

The basic structure of present-day fire temples is always the same. There are no indigenous sources older than the 19th century that describe an Iranian fire temple (the 9th century theologian Manushchir observed that they had a standard floor plan, but what this might have been is unknown), and it is possible that the temples there today have features that are originally of Indian origin.[24] On entry one comes into a large space or hall where congregation (also non-religious) or special ceremonies may take place. Off to the side of this (or sometimes a floor level up or down) the devotee enters an anteroom smaller than the hall he/she has just passed through. Connected to this anteroom, or enclosed within it, but not visible from the hall, is the innermost sanctum (in Zoroastrian terminology, the atashgah, literally 'place of the fire'[2] in which the actual fire-altar stands).

A temple at which a Yasna service (the principal Zoroastrian act of worship that accompanies the recitation of the Yasna liturgy) may be celebrated will always have, attached to it or on the grounds, at least a well or a stream or other source of 'natural' water. This is a critical requirement for the Ab-Zohr, the culminating rite of the Yasna service.

Only priests attached to a fire temple may enter the innermost sanctum itself, which is closed on at least one side and has a double domed roof. The double dome has vents to allow the smoke to escape, but the vents of the outer dome are offset from those of the inner, so preventing debris or rain from entering the inner sanctum. The sanctum is separated from the anteroom by dividers (or walls with very large openings) and is slightly raised with respect to the space around it. The wall(s) of the inner sanctum are almost always tiled or of marble, but are otherwise undecorated. There are no lights – other than that of the fire itself – in the inner sanctum. In Indian-Zoroastrian (not evident in the modern buildings in Iran) tradition the temples are often designed such that direct sunlight does not enter the sanctuary.

In one corner hangs a bell, which is rung five times a day at the boi – literally, '[good] scent'[25] – ceremony, which marks the beginning of each gah, or 'watch'. Tools for maintaining the fire – which is always fed by wood – are simply hung on the wall, or as is sometimes the case, stored in a small room (or rooms) often reachable only through the sanctum.

In India and in Indian-Zoroastrian communities overseas, non-Zoroastrians are strictly prohibited from entering any space from which one could see the fire(s). While this is not a doctrinal requirement (that is, it is not an injunction specified in the Avesta or in the so-called Pahlavi texts), it has nonetheless developed as a tradition. It is, however, mentioned in a 16th-century Rivayat epistle (R. 65). In addition, entry into any part of the facility is sometimes reserved for Zoroastrians only. This then precludes the use of temple hall for public (also secular) functions. Zoroastrians insist, though, that these restrictions are not meant to offend non-Zoroastrians, and point to similar practices in other religions. There was a custom in India that Zoroastrian women were not allowed to enter the Fire Temple and the Tower of Silence if they married a non-Zoroastrian person. This custom has been challenged before the Supreme Court of India.[26]

Worship

[edit]

When the adherent enters the sanctum he or she will offer bone-dry sandalwood (or other sweet-smelling wood) to the fire. This is in accordance with doctrinal statutes expressed in Vendidad 18.26-27, which in addition to enumerating which fuels are appropriate, also reiterates the injunctions of Yasna 3.1 and Yashts 14.55 that describe which fuels are not (in particular, any not of wood).

In present-day Zoroastrian tradition, the offering is never made directly, but placed in the care of the celebrant priest who, wearing a cloth mask over the nostrils and mouth to prevent pollution from the breath, will then – using a pair of silver tongs – place the offering in the fire. The priest will use a special ladle to proffer the holy ash to the layperson, who in turn daubs it on his or her forehead and eyelids, and may take some home for use after a Kushti ceremony.

A Zoroastrian priest does not preach or hold sermons, but rather just tends to the fire. Fire Temple attendance is particularly high during seasonal celebrations (Gahambars), and especially for the New Year (Noruz).

The priesthood is trigradal. The chief priest of each temple has the title of dastur. Consecration to this rank relieves him of the necessity of purification after the various incidents of life that a lesser priest must expiate. Ordinary priests have the title of mobad, and are able to conduct the congregational worship and such occasional functions as marriages. A mobad must be the son, grandson, or great-grandson of a mobad. The lowest rank is that of herbad, or ervad; these assist at the principal ceremonies.[27]

Gallery

[edit]-

Iranian Zoroastrians pray at Fire Temple of Baku.

-

Fire temple of Mazraeh-ye Kalantar

-

A Zoroastrian priest reads from a book while performing a sacrifice, Bernard Picart (1673–1733).

-

Three styles of a priest's hat with the mouth covered. Bernard Picart (1673–1733).

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Alternatively ātashgāh (آتشگاه). Other names include Darb-e Mehr (درب مهر) or Dar-e Mehr (در مهر, 'door/gate of light/kindness')

References

[edit]- ^ Boyce 1975.

- ^ a b Boyce, Mary (1993), "Dar-e Mehr", Encyclopaedia Iranica, vol. 6, Costa Mesa: Mazda Pub, pp. 669–670

- ^ a b c Kotwal, Firoz M. (1974), "Some Observations on the History of the Parsi Dar-i Mihrs", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 37 (3): 665, doi:10.1017/S0041977X00127557, S2CID 162207182

- ^ Boyce 1975, p. 455.

- ^ Yasna 62.1; Nyashes 5.7

- ^ "List of Fire Temples". The Parsi Directory. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ Mathai, Kamini (12 July 2010). "Parsis go all out to celebrate milestone in Chennai". The Times of India. Chennai: The Times Group. Retrieved 24 Apr 2014.

- ^ Herodotus. "131". Histories (Herodotus), Vol. I.

- ^ Strabos. "8: East of the Caspian Sea: the Sacae and the Massagetae". Geographica, Vol. XI. Section 4, page 512.

- ^ a b Boyce 1975, p. 462.

- ^ Gnoli 1993, p. 512.

- ^ Boyce 1966, p.63[full citation needed]

- ^ Boyce 1987, p. 9.

- ^ History of Civilizations of Central Asia. UNESCO. 2006. p. 49. ISBN 978-9231032110.

- ^ Lawrence, Lee (3 September 2011). "A Mysterious Stranger in China". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660.

- ^ Boyce 1987, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Boyce 1987, p. 10.

- ^ Russell, James R. (1989), "Atrušan", Encyclopaedia Iranica, vol. 3, Costa Mesa: Mazda Pub

- ^ M. Hale, Pahlavi, in "The Ancient Languages of Asia and the Americas", published by Cambridge University Press, 2008, ISBN 0-521-68494-3, p. 123.

- ^ Stausberg 2004, p. 134.

- ^ a b Jackson 1921, p. 82.

- ^ Boyce, Mary; Kotwal, Firoze (2006), "Irānshāh", Encyclopaedia Iranica, vol. 13, Costa Mesa: Mazda Pub, archived from the original on 2008-02-08, retrieved 2006-09-06

- ^ Boyce, Mary (1996). "On the Orthodoxy of Sasanian Zoroastrianism". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 59 (1): 21–22. doi:10.1017/s0041977x00028536. ISSN 0041-977X. JSTOR 619388. S2CID 162913368.

- ^ Stausberg 2004, pp. 175, 405.

- ^ Stausberg 2004, p. 115.

- ^ "Parsi Woman Excommunication Case". Supreme Court Observer. Archived from the original on 2018-01-06. Retrieved 2018-01-05.

- ^ Hastings, James, Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics, vol. 10, New York, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, p. 322]

Sources

[edit]- Boyce, Mary (1975), "On the Zoroastrian Temple Cult of Fire", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 95 (3), Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 95, No. 3: 454–465, doi:10.2307/599356, JSTOR 599356

- Boyce, Mary (1987), "Ātaškada", Encyclopaedia Iranica, vol. 3, Costa Mesa: Mazda Pub, pp. 9–10

- Drower, Elizabeth Stephens (1944), "The Role of Fire in Parsi Ritual", Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 74 (1/2), Royal Anthropological Institute: 75–89, doi:10.2307/2844296, JSTOR 2844296

- Gnoli, Gherardo (1993), "Bahram in old and middle Iranian texts", Encyclopaedia Iranica, vol. 3, Costa Mesa: Mazda Pub, pp. 510–513

- Jackson, A. V. Williams (1921). "The Location of the Farnbāg Fire, the Most Ancient of the Zoroastrian Fires". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 41: 81–106. doi:10.2307/593711. ISSN 0003-0279. JSTOR 593711.

- Schippmann, Klaus (1971). Die Iranischen Feuerheiligtümer. Religionsgeschichtliche Versuche und Vorarbeiten (in German). Berlin: de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-001879-0. OCLC 833142282.

- Shenkar, Michael (2007), "Temple Architecture in the Iranian World before the Macedonian Conquest", Iran and the Caucasus, 11 (2): 169–194, doi:10.1163/157338407X265423

- Shenkar, Michael (2011), "Temple Architecture in the Iranian World in the Hellenistic Period", In Kouremenos, A., Rossi, R., Chandrasekaran, S. (Eds.), from Pella to Gandhara: Hybridisation and Identity in the Art and Architecture of the Hellenistic East: 117–140

- Stausberg, Michael (2004), Die Religion Zarathushtras, vol. III, Stuttgart: Kohlhammer Verlag, ISBN 3-17-017120-8