Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Mandaeism

View on Wikipedia

| Mandaeism | |

|---|---|

| ࡌࡀࡍࡃࡀࡉࡅࡕࡀ | |

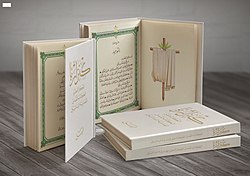

A copy of the Ginza Rabba in Arabic translation | |

| Type | Ethnic religion[1][page needed] |

| Classification | Gnosticism[1][page needed] |

| Scripture | Ginza Rabba, Qulasta, Mandaean Book of John (see more) |

| Theology | Monotheism |

| Rishama | Sattar Jabbar Hilow[2] |

| Region | Iraq, Iran and diaspora communities |

| Language | Mandaic[3] |

| Separated from | Second Temple Judaism[4][5] |

| Number of followers | c. 60,000–100,000[6][7] |

| Other names | Nasoraeanism, Sabianism[a] |

| Part of a series on |

| Mandaeism |

|---|

|

| Religion portal |

|

Mandaeism[b] (Classical Mandaic: ࡌࡀࡍࡃࡀࡉࡅࡕࡀ mandaiuta),[15] sometimes also known as Nasoraeanism or Sabianism,[a] is a Gnostic, monotheistic and ethnic religion with Greek, Iranian, and Jewish influences.[16][17][18]: 1 Its adherents, the Mandaeans, revere Adam, Abel, Seth, Enos, Noah, Shem, Aram, and especially John the Baptist. Mandaeans consider Adam, Seth, Noah, Shem, and John the Baptist prophets, with Adam being the founder of the religion and John being the greatest and final prophet.[19]: 45 [20]

The Mandaeans speak an Eastern Aramaic language known as Mandaic. The name 'Mandaean' comes from the Aramaic manda, meaning knowledge.[21][22] Within the Middle East, but outside their community, the Mandaeans are more commonly known as the صُبَّة Ṣubba (singular: Ṣubbī), or as Sabians (الصابئة, al-Ṣābiʾa). The term Ṣubba is derived from an Aramaic root related to baptism.[23] The term Sabians derives from the mysterious religious group mentioned three times in the Quran. The name of this unidentified group, which is implied in the Quran to belong to the "People of the Book" (ahl al-kitāb), was historically claimed by the Mandaeans as well as by several other religious groups in order to gain legal protection (dhimma) as offered by Islamic law.[24] Occasionally, Mandaeans are also called "Christians of Saint John", in the belief that they were a direct survival of the Baptist's disciples. Further research, however, indicates this to be a misnomer, as Mandaeans consider Jesus to be a false prophet.[25][26]

The core doctrine of the faith is known as Nāṣerutā (also spelled Nașirutha and meaning Nasoraean gnosis or divine wisdom)[27][19]: 31 (Nasoraeanism or Nazorenism) with the adherents called nāṣorāyi (Nasoraeans or Nazorenes). These Nasoraeans are divided into tarmidutā (priesthood) and mandāyutā (laity), the latter derived from their term for knowledge manda.[28]: ix [29] Knowledge (manda) is also the source for the term Mandaeism which encompasses their entire culture, rituals, beliefs and faith associated with the doctrine of Nāṣerutā. Followers of Mandaeism are called Mandaeans, but can also be called Nasoraeans (Nazorenes), Gnostics (utilizing the Greek word gnosis for knowledge) or Sabians.[28]: ix [29]

The religion has primarily been practiced around the lower Karun, Euphrates and Tigris, and the rivers that surround the Shatt al-Arab waterway, part of southern Iraq and Khuzestan province in Iran. As of 2007[update], there are believed to be between 60,000 and 70,000 Mandaeans worldwide.[6] Until the Iraq War, almost all of them lived in Iraq.[30] Many Mandaean Iraqis have since fled their country because of the turmoil created by the 2003 invasion of Iraq and subsequent occupation by U.S. armed forces, and the related rise in sectarian violence by extremists.[31] By 2007, the population of Mandaeans in Iraq had fallen to approximately 5,000.[30]

The Mandaeans have remained separate and intensely private. Reports of them and of their religion have come primarily from outsiders: particularly from Julius Heinrich Petermann, an Orientalist;[32] as well as from Nicolas Siouffi, a Syrian Christian who was the French vice-consul in Mosul in 1887,[33][34] and British cultural anthropologist Lady E. S. Drower. There is an early if highly prejudiced account by the French traveller Jean-Baptiste Tavernier[35] from the 1650s.

Etymology

[edit]The English spelling Mandaeism is a hypercorrection of Mandaism,[8][9][10][11][12][c] which is built on manda using the suffix -ism (from Ancient Greek -ισμός -ismós) and which refers to the religion of the Mandaeans.

The word Mandaean in turn derives from Mandaic Mandaiia,[36] lit. 'Mandaean' (in Neo-Mandaic: Mandāʾí[36] or Mandāyí,[36] plural Mandayānā),[36] which also derives from the word manda. On the basis of cognates in other Aramaic dialects, semiticists such as Mark Lidzbarski and Rudolf Macúch have translated the term manda as "knowledge" (cf. Imperial Aramaic: מַנְדַּע mandaʿ in Daniel 2:21, 4:31, 33, 5:12; cf. Hebrew: מַדַּע madda', with characteristic assimilation of /n/ to the following consonant, medial -nd- hence becoming -dd-).[37] This etymology suggests that the Mandaeans may well be the only sect surviving from late antiquity to identify themselves explicitly as Gnostics.[38]

Origins

[edit]According to the Mandaean text which recounts their early history, the Haran Gawaita (the Scroll of Great Revelation) which was authored between the 4th–6th centuries, the Nasoraean Mandaeans who were disciples of John the Baptist, left Jerusalem and migrated to Media in the first century CE, reportedly due to persecution.[39][40]: vi, ix The emigrants first went to Haran (possibly Harran in modern-day Turkey) or Hauran, and then to the Median hills in Iran before finally settling in southern Mesopotamia (modern day Iraq).[5] According to Richard Horsley, 'inner Hawran' is most likely Wadi Hauran in present-day Syria which the Nabataeans controlled. Earlier, the Nabataeans were at war with Herod Antipas, who had been sharply condemned by the prophet John, eventually executing him, and were thus positively predisposed toward a group loyal to John.[41]

Many scholars who specialize in Mandaeism, including Jorunn Jacobsen Buckley, agree with the historical account.[42][5][43] Others, however, argue for a southwestern Mesopotamian origin of the group.[39] Some scholars take the view that Mandaeism is older and dates back to pre-Christian times.[44] Mandaeans claim that their religion predates Judaism, Christianity and Islam,[45] and believe that they are the direct descendants of Shem, Noah's son.[46]: 186 They also believe that they are the direct descendants of John the Baptist's original Nasoraean Mandaean disciples in Jerusalem.[40]: vi, ix

History

[edit]

During Parthian rule, Mandaeans flourished under royal protection. This protection, however, did not last with the Sasanian emperor Bahram I ascending to the throne and his high priest Kartir, who persecuted all non-Zoroastrians.[5]: 4

At the beginning of the Muslim conquest of Mesopotamia in c. 640, the leader of the Mandaeans, Anush bar Danqa, is said to have appeared before the Muslim authorities, showing them a copy of the Ginza Rabba, the Mandaean holy book, and proclaiming the chief Mandaean prophet to be John the Baptist, who is also mentioned in the Quran as Yahya ibn Zakariya. This identified Mandaeans as among the ahl al-kitāb (People of the Book). Hence, Mandaeism was recognized as a legal minority religion within the Muslim Empire.[47] However, this account is likely apocryphal: since it mentions that Anush bar Danqa traveled to Baghdad, it must have occurred after the founding of Baghdad in 762, if it took place at all.[48]

Nevertheless, at some point the Mandaeans were identified as the Sabians mentioned along with the Jews, the Christians and the Zoroastrians in the Quran as People of the Book.[49] The earliest source to unambiguously do so was Ḥasan bar Bahlul (fl. 950–1000) citing the Abbasid vizier ibn Muqla (c. 885–940),[50] though it is not clear whether the Mandaeans of this period already identified themselves as Sabians or whether the claim originated with Ibn Muqla.[51] Mandaeans continue to be called Sabians to this day.[47]

Around 1290, a Catholic Dominican friar from Tuscany, Riccoldo da Monte di Croce, or Ricoldo Pennini, was in Mesopotamia where he met the Mandaeans. He described them as believing in a secret law of God recorded in alluring texts, despising circumcision, venerating John the Baptist above all and washing repeatedly to avoid condemnation by God.[52]

Mandaeans were called "Christians of Saint John" by members of the Discalced Carmelite mission in Basra during the 16th and 17th centuries, based on reports from missionaries such as Ignatius of Jesus.[25] Some Portuguese Jesuits had also met some "Saint John Christians" around the Strait of Hormuz in 1559, when the Portuguese fleet fought with the Ottoman army in Bahrain.[53]

Beliefs

[edit]Mandaeism, as the religion of the Mandaean people, is based on a set of religious creeds and doctrines. The corpus of Mandaean literature is quite large and covers topics such as eschatology, the knowledge of God, and the afterlife.[54]

According to Brikha Nasoraia:

The Mandaeans see themselves as healers of the "Worlds and Generations" (Almia u-Daria), and practitioners of the religion of Mind (Mana), Light (Nhura), Truth (Kušța), Love (Rahma/Ruhma) and Enlightenment or Knowledge (Manda).[19]: 28

Principal beliefs

[edit]- Recognition of one God known as Hayyi Rabbi, meaning The Great Life or The Great Living (God), whose symbol is Living Water (Yardena). It is, therefore, necessary for Mandaeans to live near rivers. God personifies the sustaining and creative force of the universe.[55]

- Power of Light, which is vivifying and personified by Malka d-Nhura ('King of Light'), another name for Hayyi Rabbi, and the uthras (angels or guardians) that provide health, strength, virtue and justice. The Drabsha is viewed as the symbol of Light.[55]

- Immortality of the soul: the fate of the soul is the main concern with the belief in the next life, where there is reward and punishment. There is no eternal punishment since God is merciful.[55]

Fundamental tenets

[edit]According to E. S. Drower, the Mandaean Gnosis is characterized by nine features, which appear in various forms in other gnostic sects:[27]

- A supreme formless Entity, the expression of which in time and space is a creation of spiritual, etheric, and material worlds and beings. Production of these is delegated by It to a creator or creators who originated It. The cosmos is created by Archetypal Man, who produces it in similitude to his own shape.

- Dualism: a cosmic Mother and Father, Light and Darkness, Left and Right, syzygy in cosmic and microcosmic form.

- As a feature of this dualism, counter-types (dmuta) exist in a world of ideas (Mshunia Kushta).

- The soul is portrayed as an exile, a captive, his home and origin being the supreme Entity to which he eventually returns.

- Planets and stars influence fate and human beings and are also the places of detention after death.

- A savior spirit or savior spirits that assist the soul on his journey through life and after it to 'worlds of light'.

- A cult language of symbol and metaphor. Ideas and qualities are personified.

- 'Mysteries,' i.e., sacraments to aid and purify the soul, to ensure its rebirth into a spiritual body, and its ascent from the world of matter. These are often adaptations of existing seasonal and traditional rites to which an esoteric interpretation is attached. In the case of the Naṣoraeans, this interpretation is based on the Creation story (see 1 and 2), especially on the Divine Man, Adam, as crowned and anointed King-priest.

- Great secrecy is enjoined upon initiates; full explanation of 1, 2, and 8 being reserved for those considered able to understand and preserve the gnosis.

Cosmology

[edit]

The religion extolls an intricate, multifaceted, esoteric, mythological, ritualistic, and exegetical tradition, with the emanation model of creation being the predominant interpretation.[56]

The most common name for God in Mandaeism is Hayyi Rabbi ('The Great Life' or 'The Great Living God').[57] Other names used are Mare d'Rabuta ('Lord of Greatness'), Mana Rabba ('The Great Mind'), Malka d-Nhura ('King of Light') and Hayyi Qadmaiyi ('The First Life').[46][58] Mandaeans recognize God to be the eternal, creator of all, the one and only in domination who has no partner.[59]

There are numerous uthras (angels or guardians),[60] manifested from the light, that surround and perform acts of worship to praise and honor God. Prominent amongst them include Manda d-Hayyi, who brings manda (knowledge or gnosis) to Earth,[1][page needed] and Hibil Ziwa, who conquers the World of Darkness.[18]: 206–213 Some uthras are commonly referred to as emanations and are subservient beings to 'The First Life'; their names include Second, Third, and Fourth Life (i.e. Yushamin, Abatur, and Ptahil).[61][60]

Ptahil (ࡐࡕࡀࡄࡉࡋ), the 'Fourth Life', alone does not constitute the demiurge but only fills that role insofar as he is seen as the creator of the material world with the help of the evil spirit Ruha. Ruha is viewed negatively as the personification of the lower, emotional, and feminine elements of the human psyche.[62] Therefore, the material world is a mixture of 'light' and 'dark'.[46][1][page needed] Ptahil is the lowest of a group of three emanations, the other two being Yushamin (ࡉࡅࡔࡀࡌࡉࡍ, the 'Second Life' (also spelled Joshamin)) and Abatur (ࡀࡁࡀࡕࡅࡓ), the 'Third Life'. Abatur's demiurgic role consists of weighing the souls of the dead to determine their fate. The role of Yushamin, the first emanation, is more obscure; wanting to create a world of his own, he was punished for opposing the King of Light ('The First Life') but was ultimately forgiven.[63][28]

As is also the case among the Essenes, it is forbidden for a Mandaean to reveal the names of the angels to a gentile.[46]: 94

Chief prophets

[edit]

Mandaeans recognize several prophets. John the Baptist, known in Mandaic as Yuhana Maṣbana (ࡉࡅࡄࡀࡍࡀ ࡌࡀࡑࡁࡀࡍࡀ)[64] or Yuhana bar Zakria (John, son of Zechariah),[65] is accorded a special status, higher than his role in either Christianity or Islam. Mandaeans do not consider John to be the founder of their religion, but they revere him as their greatest teacher who renews and reforms their ancient faith,[5]: 101 [66] tracing their beliefs back to Adam. John is believed to be a messenger of Light (nhura) and Truth (kushta) who possessed the power of healing and full Gnosis (manda).[19]: 48

Mandaeism does not consider Abraham, Moses, or Jesus to be Mandaean prophets. However, it teaches the belief that Abraham and Jesus were originally Mandaean priests.[40][5][67] They recognize other prophetic figures from the Abrahamic religions, such as Adam, his sons Hibil (Abel) and Sheetil (Seth), and his grandson Anush (Enosh), as well as Nuh (Noah), Sam (Shem), and Ram (Aram), whom they consider to be their direct ancestors. Mandaeans consider Adam, Seth, Noah, Shem, and John the Baptist to be prophets, with Adam the founder and John the greatest and final prophet.[19]: 45 [20]

Scriptures and literature

[edit]

The Mandaeans have a large corpus of religious scriptures, the most important of which is the Ginza Rabba or Ginza, a collection of history, theology, and prayers.[68] The Ginza Rabba is divided into two halves—the Genzā Smālā or Left Ginza, and the Genzā Yeminā or Right Ginza. By consulting the colophons in the Left Ginza, Jorunn J. Buckley has identified an uninterrupted chain of copyists to the late second or early third century.[69] The colophons attest to the existence of the Mandaeans during the late Parthian Empire.

The oldest texts are lead amulets from about the third century CE, followed by incantation bowls from about 600 CE. The important religious texts survived in manuscripts not older than the sixteenth century, with most coming from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[70]

Mandaean religious texts may have been originally orally transmitted before being written down by scribes, making dating and authorship difficult.[46]: 20

Another important text is the Haran Gawaita, which tells the history of the Mandaeans. According to this text, a group of Nasoraeans (Mandean priests) left Judea before the destruction of Jerusalem in the first century CE and settled within the Parthian Empire.[5]

Other important books include the Qulasta, the canonical prayerbook of the Mandaeans, which was translated by E. S. Drower.[71] One of the chief works of Mandaean scripture, accessible to laymen and initiates alike, is the Mandaean Book of John, which includes a dialogue between John and Jesus. In addition to the Ginza, Qulasta, and Draša d-Yahya, there is the Diwan Abatur, which contains a description of the 'regions' the soul ascends through, and the Book of the Zodiac (Asfar Malwāshē). Finally, some pre-Muslim artifacts contain Mandaean writings and inscriptions, such as some Aramaic incantation bowls.

Mandaean ritual commentaries (esoteric exegetical literature), which are typically written in scrolls rather than codices, include:[1][page needed]

- The Thousand and Twelve Questions (Alf Trisar Šuialia)

- The Coronation of the Great Šišlam

- The Great "First World"

- The Lesser "First World"

- The Scroll of Exalted Kingship

- The Baptism of Hibil Ziwa

The language in which the Mandaean religious literature was originally composed is known as Mandaic, a member of the Aramaic group of dialects. It is written in the Mandaic script, a cursive variant of the Parthian chancellery script. Many Mandaean laypeople do not speak this language, although some members of the Mandaean community resident in Iran and Iraq continue to speak Neo-Mandaic, a modern version of this language.

If you see anyone hungry, feed him; if you see anyone thirsty, give him a drink.

— Right Ginza I.105

Give alms to the poor. When you give do not attest it. If you give with your right hand do not tell your left hand. If you give with your left hand do not tell your right hand.

Ye the chosen ones ... Do not wear iron and weapons; let your weapons be knowledge and faith in the God of the World of Light. Do not commit the crime of killing any human being.

Ye the chosen ones ... Do not rely on kings and rulers of this world, do not use soldiers and weapons or wars; do not rely on gold or silver, for they all will forsake your soul. Your souls will be nurtured by patience, love, goodness and love for Life.

— Right Ginza II.i.34[72]

Worship and rituals

[edit]

The two most important ceremonies in Mandaean worship are baptism (Masbuta) and 'the ascent' (Masiqta – a mass for the dead or ascent of the soul ceremony). Unlike in Christianity, baptism is not a one-off event but is performed every Sunday, the Mandaean holy day, as a ritual of purification. Baptism usually involves full immersion in flowing water, and all rivers considered fit for baptism are called Yardena (after the River Jordan). After emerging from the water, the worshipper is anointed with holy sesame oil and partakes in a communion of sacramental bread and water. The ascent of the soul ceremony, called the masiqta, can take various forms, but usually involves a ritual meal in memory of the dead. The ceremony is believed to help the souls of the departed on their journey through purgatory to the World of Light.[73][46]

Other rituals for purification include the Rishama and the Tamasha which, unlike Masbuta, can be performed without a priest.[46] The Rishama (signing) is performed before prayers and involves washing the face and limbs while reciting specific prayers. It is performed daily, before sunrise, with hair covered and after defecation or before religious ceremonies[55] (see wudu). The Tamasha is a triple immersion in the river without a requirement for a priest. It is performed by women after menstruation or childbirth, men and women after sexual activity or nocturnal emission, touching a corpse or any other type of defilement[55] (see tevilah). Ritual purification also applies to fruits, vegetables, pots, pans, utensils, animals for consumption and ceremonial garments (rasta).[55] Purification for a dying person is also performed. It includes bathing involving a threefold sprinkling of river water over the person from head to feet.[55]

-

Mandaean Beth Manda (Mashkhanna) in Baghdad, 2024

Mandaean Beth Manda (Mashkhanna) in Baghdad, 2024 -

Door entrance to the Mashkhanna, written in Classical Mandaic and Arabic. Transalation: ࡁࡔࡅࡌࡀࡉࡄࡅࡍ ࡖࡄࡉࡉࡀ ࡓࡁࡉࡀ = "in their name, the great living one" and on the doors, following: ࡊࡅࡔࡈࡀ ࡀࡎࡉࡍࡊࡅࡍ = "truth be upon you"

Door entrance to the Mashkhanna, written in Classical Mandaic and Arabic. Transalation: ࡁࡔࡅࡌࡀࡉࡄࡅࡍ ࡖࡄࡉࡉࡀ ࡓࡁࡉࡀ = "in their name, the great living one" and on the doors, following: ࡊࡅࡔࡈࡀ ࡀࡎࡉࡍࡊࡅࡍ = "truth be upon you" -

Inside the Mashkhanna

A Mandaean's grave must be in the north–south direction so that if the dead Mandaean were stood upright, they would face north.[46]: 184 Similarly, Essene graves are also oriented north–south.[74] Mandaeans must face north during prayers, which are performed three times a day.[75][76][46] Daily prayer in Mandaeism is called brakha.

Zidqa (almsgiving) is also practiced in Mandaeism, with Mandaean laypeople regularly offering alms to priests.

A mandī (Arabic: مندى) (beth manda) or mashkhanna[77] is a place of worship for followers of Mandaeism. A mandī must be built beside a river in order to perform maṣbuta (baptism) because water is an essential element in the Mandaean faith. Modern mandīs sometimes have a bath inside a building instead. Each mandi is adorned with a drabsha, which is a banner in the shape of a cross, made of olive wood half covered with a piece of white pure silk cloth and seven branches of myrtle. The drabsha is not identified with the Christian cross. Instead, the four arms of the drabsha symbolize the four corners of the universe, while the pure silk cloth represents the Light of God.[78] The seven branches of myrtle represent the seven days of creation.[79][80]

Mandaeans believe in marriage (qabin) and procreation, placing a high priority upon family life and in the importance of leading an ethical and moral lifestyle. Polygyny is accepted, though it is uncommon.[81][82] They are pacifist and egalitarian, with the earliest attested Mandaean scribe being a woman, Shlama Beth Qidra, who copied the Left Ginza sometime in the second century CE.[17] There is evidence for women priests, especially in the pre-Islamic era.[83] They believe the creator created the human body complete, so no part of it should be removed or cut off, hence circumcision is considered bodily mutilation for Mandaeans and therefore forbidden.[55][46] Mandaeans abstain from strong drink and most red meat, however meat consumed by Mandaeans must be slaughtered according to the proper rituals. The approach to the slaughter of animals for consumption is always apologetic.[55] On some days, they refrain from eating meat.[84][page needed] Fasting in Mandaeism is called sauma. Mandaeans have an oral tradition that some were originally vegetarian.[85]

Priests

[edit]

There is a strict division between Mandaean laity and the priests. According to E. S. Drower (The Secret Adam, p. ix):

[T]hose amongst the community who possess secret knowledge are called Naṣuraiia—Naṣoraeans (or, if the emphatic ‹ṣ› is written as ‹z›, Nazorenes). At the same time the ignorant or semi-ignorant laity are called 'Mandaeans', Mandaiia—'gnostics.' When a man becomes a priest he leaves 'Mandaeanism' and enters tarmiduta, 'priesthood.' Even then he has not attained to true enlightenment, for this, called 'Naṣiruta', is reserved for a very few. Those possessed of its secrets may call themselves Naṣoraeans, and 'Naṣoraean' today indicates not only one who observes strictly all rules of ritual purity, but one who understands the secret doctrine.[86]

There are three grades of priesthood in Mandaeism: the tarmidia (ࡕࡀࡓࡌࡉࡃࡉࡀ) "disciples" (Neo-Mandaic tarmidānā), the ganzibria (ࡂࡀࡍࡆࡉࡁࡓࡉࡀ) "treasurers" (from Old Persian ganza-bara "id.", Neo-Mandaic ganzeḇrānā) and the rišama (ࡓࡉࡔࡀࡌࡀ) "leader of the people". Ganzeḇrā, a title which appears first in a religious context in the Aramaic ritual texts from Persepolis (c. third century BCE), and which may be related to the kamnaskires (Elamite <qa-ap-nu-iš-ki-ra> kapnuskir "treasurer"), title of the rulers of Elymais (modern Khuzestan) during the Hellenistic age. Traditionally, any ganzeḇrā who baptizes seven or more ganzeḇrānā may qualify for the office of rišama. The current rišama of the Mandaean community in Iraq is Sattar Jabbar Hilo al-Zahrony. In Australia, the Mandaean rišama is Salah Chohaili.[2][87][88]

The contemporary priesthood can trace its immediate origins to the first half of the nineteenth century. In 1831, an outbreak of cholera in Shushtar, Iran devastated the region and eliminated most, if not all, of the Mandaean religious authorities there. Two of the surviving acolytes (šgandia), Yahia Bihram and Ram Zihrun, reestablished the priesthood in Suq al-Shuyukh on the basis of their own training and the texts that were available to them.[89]

In 2009, there were two dozen Mandaean priests in the world.[90] However, according to the Mandaean Society in America, the number of priests has been growing in recent years.

Scholarship

[edit]

According to Edmondo Lupieri, as stated in his article in Encyclopædia Iranica, "The possible historical connection with John the Baptist, as seen in the newly translated Mandaean texts, convinced many (notably R. Bultmann) that it was possible, through the Mandaean traditions, to shed some new light on the history of John and on the origins of Christianity. This brought around a revival of the otherwise almost fully abandoned idea of their origins in Israel. As the archeological discovery of Mandaean incantation bowls and lead amulets proved a pre-Islamic Mandaean presence in the southern Mesopotamia, scholars were obliged to hypothesize otherwise unknown persecutions by Jews or by Christians to explain the reason for Mandaeans' departure from Israel." Lupieri believes Mandaeism is a post-Christian southern Mesopotamian Gnostic off-shoot and claims that Zazai d-Gawazta to be the founder of Mandaeism in the second century. Jorunn J. Buckley refutes this by confirming scribes that predate Zazai who copied the Ginza Rabba.[69][43] In addition to Edmondo Lupieri, Christa Müller-Kessler argues against the Israelite origin theory of the Mandaeans claiming that the Mandaeans are Mesopotamian.[91] Edwin Yamauchi believes Mandaeism's origin lies in the Transjordan, where a group of 'non-Jews' migrated to Mesopotamia and combined their Gnostic beliefs with indigenous Mesopotamian beliefs at the end of the second century CE.[92][93] Kevin van Bladel claims that Mandaeism originated no earlier than fifth century Sassanid Mesopotamia, a thesis which has been criticized by James F. McGrath.[94]

Brikha Nasoraia, a Mandaean priest and scholar, accepts a two-origin theory in which he considers the contemporary Mandaeans to have descended from both a line of Mandaeans who had originated from the Jordan valley of Israel, as well as another group of Mandaeans (or Gnostics) who were indigenous to southern Mesopotamia. Thus, the historical merging of the two groups gave rise to the Mandaeans of today.[95]: 55

Scholars specializing in Mandaeism such as Kurt Rudolph, Mark Lidzbarski, Rudolf Macúch, Ethel S. Drower, Eric Segelberg, James F. McGrath, Charles G. Häberl, Jorunn Jacobsen Buckley, and Şinasi Gündüz argue for an Israelite origin. The majority of these scholars believe that the Mandaeans likely have a historical connection with John the Baptist's inner circle of disciples.[96][97][68][98] Charles Häberl, who is also a linguist specializing in Mandaic, finds Jewish Aramaic, Samaritan Aramaic, Hebrew, Greek and Latin influence on Mandaic and accepts Mandaeans having a "shared Israelite history with Jews".[99][100] In addition, scholars such as Richard August Reitzenstein, Rudolf Bultmann, G. R. S. Mead, Samuel Zinner, Richard Thomas, J. C. Reeves, Gilles Quispel, and K. Beyer also argue for a Judea/Palestine or Jordan Valley origin for the Mandaeans.[101][102][103][104][105][106] James McGrath and Richard Thomas believe there is a direct connection between Mandaeism and pre-exilic traditional Israelite religion.[107][108] Lady Ethel S. Drower "sees early Christianity as a Mandaean heresy"[109] and adds "heterodox Judaism in Galilee and Samaria appears to have taken shape in the form we now call gnostic, and it may well have existed some time before the Christian era."[110] Barbara Thiering questions the dating of the Dead Sea Scrolls and suggests that the Teacher of Righteousness (leader of the Essenes) was John the Baptist.[111] Jorunn J. Buckley accepts Mandaeism's Israelite or Judean origins[5]: 97 and adds:

[T]he Mandaeans may well have become the inventors of – or at least contributors to the development of – Gnosticism ... and they produced the most voluminous Gnostic literature we know, in one language ... influenc[ing] the development of Gnostic and other religious groups in late antiquity [e.g. Manichaeism, Valentianism].[5]: 109

Other names

[edit]Sabians

[edit]During the 9th and 10th centuries several religious groups came to be identified with the mysterious Sabians (sometimes also spelled 'Sabaeans' or 'Sabeans', but not to be confused with the Sabaeans of South Arabia) mentioned alongside the Jews, the Christians, and the Zoroastrians in the Quran. It is implied in the Quran that the Sabians belonged to the 'People of the Book' (ahl al-kitāb).[112] The religious groups who purported to be the Sabians mentioned in the Quran included the Mandaeans, but also various pagan groups in Harran (Upper Mesopotamia) and the marshlands of southern Iraq. They claimed the name in order to be recognized by the Muslim authorities as a people of the book deserving of legal protection (dhimma).[49] The earliest source to unambiguously apply the term 'Sabian' to the Mandaeans was al-Hasan ibn Bahlul (fl. 950–1000) citing the Abbasid vizier Abu Ali Muhammad ibn Muqla (c. 885–940).[50] However, it is not clear whether the Mandaeans of this period identified themselves as Sabians or whether the claim originated with Ibn Muqla.[51]

Some modern scholars have identified the Sabians mentioned in the Quran as Mandaeans,[113] although many other possible identifications have been proposed.[114] Some scholars believe it is impossible to establish their original identity with any degree of certainty.[115] Mandaeans continue to be called Sabians to this day.[116]

Nasoraeans

[edit]The Haran Gawaita uses the name Nasoraeans for the Mandaeans arriving from Jerusalem meaning guardians or possessors of secret rites and knowledge.[117] Scholars such as Kurt Rudolph, Rudolf Macúch, Mark Lidzbarski and Ethel S. Drower and James F. McGrath connect the Mandaeans with the Nasaraeans described by Epiphanius, a group within the Essenes according to Joseph Lightfoot.[118][119][98] Epiphanius says (29:6) that they existed before Christ. That is questioned by some, but others accept the pre-Christian origin of the Nasaraeans.[120][121]

The Nasaraeans – they were Jews by nationality – originally from Gileaditis, Bashanitis and the Transjordan ... They acknowledged Moses and believed that he had received laws – not this law, however, but some other. And so, they were Jews who kept all the Jewish observances, but they would not offer sacrifice or eat meat. They considered it unlawful to eat meat or make sacrifices with it. They claim that these Books are fictions, and that none of these customs were instituted by the fathers. This was the difference between the Nasaraeans and the others.

— Epiphanius's Panarion 1:18

Relations with other groups

[edit]Elkesaites

[edit]The Elkesaites were a Judeo-Christian baptismal sect that originated in the Transjordan and were active between 100 and 400 CE.[122] The members of this sect, like the Mandaeans, performed frequent baptisms for purification and had a Gnostic disposition.[122][46]: 123 The sect is named after its leader Elkesai.[123]

The Church Father Epiphanius (writing in the fourth century CE) seems to make a distinction between two main groups within the Essenes:[124] "Of those that came before his [Elxai (Elkesai), an Ossaean prophet] time and during it, the Ossaeans and the Nasaraeans."[125]

Epiphanius describes the Ossaeans as following:

After this Nasaraean sect in turn comes another closely connected with them, called the Ossaeans. These are Jews like the former ... originally came from Nabataea, Ituraea, Moabitis, and Arielis, the lands beyond the basin of what sacred scripture called the 'Salt Sea'. This is the one which is called the 'Dead Sea' ... The man called Elxai joined them later, in the reign of the emperor Trajan after the Saviour's incarnation, and he was a false prophet. He wrote a book, supposedly by prophecy or as though by inspired wisdom. They also say that there was another person, Iexaeus, Elxai's brother ... As has been said earlier, Elxai was connected with the sect I have mentioned, the one called the Ossaean. Even today there are still remnants of it in Nabataea, which is also called Peraea near Moabitis; this people is now known as the Sampsaean ... For he [Elxai] forbids prayer facing east. He claims that one should not face this direction, but should face Jerusalem from all quarters. Some must face Jerusalem from east to west, some from west to east, some from north to south and south to north, so that Jerusalem is faced from every direction ... Though it is different from the other six of these seven sects, it causes schism only by forbidding the books of Moses like the Nasaraean.

— Epiphanius's Panarion 1:19

Ossaeans have abandoned Judaism for the sect of the Sampsaeans, who are no longer either Jews or Christians.

— Epiphanius's Panarion 1:20

Essenes

[edit]The Essenes were a mystic Jewish sect during the Second Temple period that flourished from the second century BCE to the first century CE.[126]

Early Mandaean religious concepts and terminologies recur in the Dead Sea Scrolls, and Yardena (Jordan) has been the name of every baptismal water in Mandaeism.[127] Mara d-Rabuta (Mandaic: "Lord of Greatness", one of the names for Hayyi Rabbi) is found in the Genesis Apocryphon II, 4.[128] An early Mandaean self-appellation is bhiria zidqa, meaning 'elect of righteousness' or 'the chosen righteous', a term found in the Book of Enoch and Genesis Apocryphon II, 4.[129][117][130]: 52 As Nasoraeans, Mandaeans believe that they constitute the true congregation of bnia nhura, meaning 'Sons of Light', a term used by the Essenes.[19]: 50 [131] Mandaean scripture affirms that the Mandaeans descend directly from John the Baptist's original Nasoraean Mandaean disciples in Jerusalem and there are numerous similarities between John's movement and the Essenes.[40]: vi, ix [132] Similar to the Essenes, it is forbidden for a Mandaean to reveal the names of the angels to a gentile.[46]: 94 Essene graves are oriented north–south[74] and a Mandaean's grave must also be in the north–south direction so that if the dead Mandaean were stood upright, they would face north.[46]: 184 Mandaeans have an oral tradition that some were originally vegetarian[85] and also similar to the Essenes, they are pacifists.[133]: 47 [30]

The bit manda (beth manda) is described as biniana rba ḏ-šrara ("the Great building of Truth") and bit tušlima ("house of Perfection") in Mandaean texts such as the Qulasta, Ginza Rabba, and the Mandaean Book of John. The only known literary parallels are in Essene texts from Qumran such as the Community Rule, which has similar phrases such as the "house of Perfection and Truth in Israel" (Community Rule 1QS VIII 9) and "house of Truth in Israel."[134]

Bana'im

[edit]Bana'im were a minor Jewish sect and an offshoot of the Essenes during the second century in Israel.[135][136] The Bana'im put heavy emphasis on the cleanliness of clothing since they believed that garments cannot even have a small mudstain before dipping in purifying water. There exists considerable debate around their activities in Israel and the meaning of the name, some believe that they would put heavy emphasis on the study of the creation of the world, while some believe that the Bana'im were an Essene order employed with the ax and shovel. Other scholars instead have suggested that the name of the Bana'im is derived from the Greek word for "bath". In this case the sect would be similar to the Hemerobaptists or Tovelei Shaḥarit.[137][better source needed]

Hemerobaptists

[edit]Hemerobaptists (Heb. Tovelei Shaḥarit; 'Morning Bathers') were an ancient religious sect that practiced daily baptism. They were likely a division of the Essenes.[137] In the Clementine Homilies (ii. 23), John the Baptist and his disciples are mentioned as Hemerobaptists. The Mandaeans have been associated with the Hemerobaptists on account of both practicing frequent baptism and Mandaeans believing they are disciples of John.[138][40][139]

Maghāriya

[edit]Maghāriya were a minor Jewish sect that appeared in the first century BCE, their special practice was the keeping of all their literature in caves in the surrounding hills of Israel. They made their own commentaries on the Bible and the law. The Maghāriya believed that God is too sublime to mingle with matter, thus they did not believe that God directly created the world, but that an angel, which represents God created the earth which is similar to the Mandaean demiurgic Ptahil. Some scholars have identified the Maghāriya with the Essenes or the Therapeutae.[137][136][140]

Nasaraeans

[edit]see Nasoraeans

Ossaeans

[edit]see Elkesaites

Kabbalah

[edit]Nathaniel Deutsch writes:

Initially, these interactions [between Mandaeans and Jewish mystics in Babylonia from Late Antiquity to the medieval period] resulted in shared magical and angelogical traditions. During this phase the parallels which exist between Mandaeism and Hekhalot mysticism would have developed. At some point, both Mandaeans and Jews living in Babylonia began to develop similar cosmogonic and theosophic traditions involving an analogous set of terms, concepts, and images. At present it is impossible to say whether these parallels resulted primarily from Jewish influence on Mandaeans, Mandaean influence on Jews, or from cross fertilization. Whatever their original source, these traditions eventually made their way into the priestly – that is, esoteric – Mandaean texts ... and into the Kabbalah.[141]: 222

R.J. Zwi Werblowsky suggests Mandaeism has more commonality with Kabbalah than with Merkabah mysticism such as cosmogony and sexual imagery. The Thousand and Twelve Questions, Scroll of Exalted Kingship, and Alma Rišaia Rba link the alphabet with the creation of the world, a concept found in Sefer Yetzirah and the Bahir.[141]: 217 Mandaean names for uthras have been found in Jewish magical texts. Abatur appears to be inscribed inside a Jewish magic bowl in a corrupted form as "Abiṭur". Ptahil is found in Sefer HaRazim listed among other angels who stand on the ninth step of the second firmament.[142]: 210–211

Manichaeans

[edit]According to the Fihrist of ibn al-Nadim, the Mesopotamian prophet Mani, the founder of Manichaeism, was brought up within the Elkesaite (Elcesaite or Elchasaite) sect, this being confirmed more recently by the Cologne Mani Codex. None of the Manichaean scriptures has survived in its entirety, and it seems that the remaining fragments have not been compared to the Ginza Rabba. Mani later left the Elkasaites to found his own religion. In a comparative analysis, the Swedish Egyptologist Torgny Säve-Söderbergh indicated that Mani's Psalms of Thomas was closely related to Mandaean texts.[143] According to E. S. Drower, "some of the most ancient Manichaean psalms, the Coptic Psalms of Thomas, were paraphrases and even word-for-word translations of Mandaic originals; prosody and phrase offering proof that the Manichaean was the borrower and not vice-versa."[40]: IX

An extensive discussion of the relationships between Mandaeism and Manichaeism can be found in Băncilă (2018).[144]

Samaritan Baptist sects

[edit]According to Magris, Samaritan Baptist sects were an offshoot of John the Baptist.[145] One offshoot was in turn headed by Dositheus, Simon Magus, and Menander. It was in this milieu that the idea emerged that the world was created by ignorant angels. Their baptismal ritual removed the consequences of sin, and led to a regeneration by which natural death, which was caused by these angels, was overcome.[145] The Samaritan leaders were viewed as "the embodiment of God's power, spirit, or wisdom, and as the redeemer and revealer of 'true knowledge'".[145]

The Simonians were centered on Simon Magus, the magician baptised by Philip and rebuked by Peter in Acts 8, who became in early Christianity the archetypal false teacher. The ascription by Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, and others of a connection between schools in their time and the individual in Acts 8 may be as legendary as the stories attached to him in various apocryphal books. Justin Martyr identifies Menander of Antioch as Simon Magus' pupil. According to Hippolytus, Simonianism is an earlier form of Valentinianism.[146]

Sethians

[edit]Kurt Rudolph has observed many parallels between Mandaean texts and Sethian Gnostic texts from the Nag Hammadi library.[147] Birger A. Pearson also compares the "Five Seals" of Sethianism, which he believes is a reference to quintuple ritual immersion in water, to Mandaean masbuta.[148] According to Buckley (2010), "Sethian Gnostic literature ... is related, perhaps as a younger sibling, to Mandaean baptism ideology."[149]

Valentinians

[edit]A Mandaean baptismal formula was adopted by Valentinian Gnostics in Rome and Alexandria in the second century CE.[5]: 109

Demographics

[edit]

It is estimated that there are between 60,000 and 100,000 Mandaeans worldwide.[80] Their proportion in their native lands has collapsed because of the Iraq War, with most of the community relocating to nearby Iran, Syria, and Jordan. There are approximately 2,500 Mandaeans in Jordan.[150]

In 2011, Al Arabiya put the number of hidden and unaccounted for Iranian Mandaeans in Iran as high as 60,000.[151] According to a 2009 article in The Holland Sentinel, the Mandaean community in Iran has also been dwindling, numbering between 5,000 and, at most, 10,000 people.

Many Mandaeans have formed diaspora communities outside the Middle East in Sweden, Netherlands, Germany, United States, Canada, New Zealand, UK and especially Australia, where around 10,000 now reside, mainly around Sydney, representing 15% of the total world Mandaean population.[152]

Approximately 1,000 Iranian Mandaeans have emigrated to the United States, since the US State Department in 2002 granted them protective refugee status, which was also later accorded to Iraqi Mandaeans in 2007.[153] A community estimated at 2,500 members live in Worcester, Massachusetts, where they began settling in 2008. Most emigrated from Iraq.[154]

Mandaeism does not allow conversion, and the religious status of Mandaeans who marry outside the faith and their children is disputed.[90]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b The term 'Nasoraean' (lit. 'from Nazareth') is used for the initiated among the Mandaeans. For other religious groups sharing a similar name, see Nazarene (sect).

The term 'Sabianism' is derived from the mysterious Sabians mentioned in the Quran, a name historically claimed by several religious groups. For other religions sometimes called 'Sabianism', see Sabians#Pagan Sabians. - ^ Also spelled Mandaism[8][9][10][11][12] in accordance with the word’s etymology (; see also Greek Μανδαϊσμός[13] Mandaïsmós and its regular Latinization Mandaismus.[14]

- ^ Greek: Μανδαϊσμός[13] Mandaïsmós; Latin: Mandaismus.[14]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Buckley 2002.

- ^ a b "His Holiness Sattar Jabbar Hilo". Global Imams Council. 20 November 2021. Archived from the original on 4 February 2022. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

His Holiness Ganzevra Sattar Jabbar Hilo al-Zahrony, the worldwide head of The Sabian Mandeans, is a member of the Interfaith Network of the Global Imams Council. [failed verification] - ^ E. S. Drower, The Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran (Leiden: Brill, 1937; reprint 1962); Kurt Rudolph, Die Mandäer II. Der Kult (Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht; Göttingen, 1961; Kurt Rudolph, Mandaeans (Leiden: Brill, 1967); Christa Müller-Kessler, "Sacred Meals and Rituals of the Mandaeans", in David Hellholm, Dieter Sänger (eds.), Sacred Meal, Communal Meal, Table Fellowship, and the Eucharist: Late Antiquity, Early Judaism, and Early Christianity, Vol. 3 (Tübingen: Mohr, 2017), pp. 1715–1726, pls.

- ^ King, Karen L. (2005). What is Gnosticism?. p. 140.

And sixty thousand Nasoraeans abandoned the Sign of the Seven and entered the Median Hills, a place where we were free from domination by all other races.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Buckley, Jorunn Jacobsen (2010). "4. Turning the Tables on Jesus: The Mandaean View". In Horsley, Richard (ed.). Christian Origins. A People's History of Christianity. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. pp. 94–111. ISBN 978-1-4514-1664-0.

- ^ a b Thaler, Kai (9 March 2007). "Iraqi minority group needs U.S. attention". Yale Daily News. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ "The Mandaeans – Who are the Mandaeans?". The Worlds of Mandaean Priests. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- ^ a b Higgins 1836, p. 657.

- ^ a b Wright 1871, p. xiv.

- ^ a b Hirschfeld 1898, p. 908.

- ^ a b Gaster 1925, p. 87.

- ^ a b Dodd 1968.

- ^ a b Αριστοτέλειο Πανεπιστήμιο Θεσσαλονίκης & Κέντρο Βυζαντινών Ερευνών 2010, p. 184.

- ^ a b Hoffmann & Merx 1867, p. 253.

- ^ "FORM 10-K - Annual report pursuant to section 13 or 15(d) of the securities exchange act of 1934" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 May 2025.

- ^ Rudolph, Kurt; Duling, Dennis C.; Modschiedler, John (1969). "Problems of a History of the Development of the Mandaean Religion". History of Religions. 8 (3): 210–235. doi:10.1086/462585. ISSN 0018-2710. JSTOR 1061760. S2CID 162362180.

[Wilhelm] Brandt maintains that the oldest layer of Mandaean tradition is pre-Christian. He designates it "polytheistic material,'" which is nourished above all from "semitic nature religion" (to which he also accords baptismal and water rites) and "Chaldaean philosophy." Gnostic, Greek, Persian, and Jewish conceptions were added and assimilated to it. [...] A newer trend of Mandaean theology was first capable of bringing about a reformation by attaching itself to Persian models; this is the school of the so-called "teaching of the king of light" (Lichtkonigslehre), as Brandt has named it. [...] Both of the central principles of Mandeism, Light and Life, attached themselves to Iranian and Semitic conceptions.

- ^ a b Buckley 2002, p. 4.

- ^ a b Al-Saadi, Qais; Al-Saadi, Hamed (2019). Ginza Rabba (2nd ed.). Germany: Drabsha.

- ^ a b c d e f Nasoraia, Brikhah S. (2012). "Sacred Text and Esoteric Praxis in Sabian Mandaean Religion" (PDF).

- ^ a b mandaean الصابئة المندايين (21 November 2019). "تعرف على دين المندايي في ثلاث دقائق". YouTube. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ^ Rudolph 1977, p. 15.

- ^ Fontaine, Petrus Franciscus Maria (January 1990). Dualism in ancient Iran, India and China. The Light and the Dark. Vol. 5. Brill. ISBN 9789050630511.

- ^ Häberl 2009, p. 1

- ^ De Blois 1960–2007; van Bladel 2017, p. 5.

- ^ a b Edmondo, Lupieri (2004). "Friar of Ignatius of Jesus (Carlo Leonelli) and the First "Scholarly" Book on Mandaeaism (1652)". ARAM Periodical. 16 (Mandaeans and Manichaeans): 25–46. ISSN 0959-4213.

- ^ Burkitt, F. C. (1928). "The Mandaeans". The Journal of Theological Studies. 29 (115): 225–235. doi:10.1093/jts/os-XXIX.115.225. ISSN 0022-5185. JSTOR 23950943.

When they were first discovered by Europeans in the 17th century, and it was found that they were neither Catholics nor Protestants but that they made much of baptism and honoured John the Baptist, they were called Christians of St John, in the belief that they were a direct survival of the Baptist's disciples. Further research, however, made it quite clear that they were not Christians or Jews at all, in any ordinary sense of the word. They regard 'Jesus Messiah' as a false prophet, and 'the Holy Spirit' as a female demon, and they denounce the Jews and all their ways.

- ^ a b Drower 1960b, p. xvi.

- ^ a b c Häberl & McGrath 2019

- ^ a b Drower 1960b.

- ^ a b c Deutsch, Nathaniel (6 October 2007). "Save the Gnostics". The New York Times.

- ^ Crawford, Angus (4 March 2007). "Iraq's Mandaeans 'face extinction'". BBC News. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ Foerster, Werner (1974). Gnosis: A Selection of Gnostic texts. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. p. 126. ISBN 9780198264347.

- ^ Lupieri 2001, p. 12.

- ^ Häberl 2009, p. 18: "In 1873, the French vice-consul in Mosul, a Syrian Christian by the name of Nicholas Siouffi, sought Mandaean informants in Baghdad without success."

- ^ Tavernier, J.-B. (1678). The Six Voyages of John Baptista Tavernier. Translated by Phillips, J. pp. 90–93.

- ^ a b c d Häberl 2009, p. 1.

- ^ Angel Sáenz-Badillos, A History of the Hebrew Language. Cambridge University Press, 1993 (ISBN 978-0521556347), p. 36 et passim.

- ^ McGrath, James (23 January 2015), "The First Baptists, The Last Gnostics: The Mandaeans", YouTube-A lunchtime talk about the Mandaeans by Dr. James F. McGrath at Butler University, retrieved 7 May 2022

- ^ a b "Mandaeanism | religion". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Drower, Ethel Stefana (1953). The Haran Gawaita and the Baptism of Hibil-Ziwa. Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana.

- ^ Horsley, Richard (2010). Christian Origins. Fortress Press. ISBN 9781451416640.

- ^ Porter, Tom (22 December 2021). "Religion Scholar Jorunn Buckley Honored by Library of Congress". Bowdoin. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- ^ a b Lupieri, Edmondo F. (7 April 2008). "Mandaeans i. History". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ Duchesne-Guillemin, Jacques (1978). Etudes mithriaques. Téhéran: Bibliothèque Pahlavi. p. 545.

- ^ "The People of the Book and the Hierarchy of Discrimination". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 1 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Drower, Ethel Stefana (1937). The Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran. Clarendon Press.

- ^ a b Buckley 2002, p. 5.

- ^ van Bladel 2017, pp. 14, cf. pp. 7–15.

- ^ a b van Bladel 2017, p. 5.

- ^ a b van Bladel 2017, p. 47; on the identification of al-Hasan ibn Bahlul's source (named merely "Abu Ali") as Abu Ali Muhammad ibn Muqla, see p. 58.

- ^ a b van Bladel 2017, p. 54. On Ibn Muqla's possible motivations for applying the Quranic epithet to the Mandaeans rather than to the Harranian pagans (who were more commonly identified as 'Sabians' in the Baghdad of his time), see p. 66.

- ^ Lupieri 2001, p. 65.

- ^ Lupieri 2001, pp. 69, 87.

- ^ Segelberg, Eric (1958). Maşbūtā. Studies in the Ritual of the Mandæan Baptism. Uppsala, Sweden: Almqvist & Wiksells.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Mandaean Awareness and Guidance Board (28 May 2014). "Mandaean Beliefs & Mandaean Practices". Mandaean Associations Union. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

- ^ Buckley 2002, p. 7, 8.

- ^ Nashmi, Yuhana (24 April 2013), "Contemporary Issues for the Mandaean Faith", Mandaean Associations Union, retrieved 1 November 2021

- ^ Rudolph 1977.

- ^ Shak, Hanish (2018). "The Mandaeans in Iraq". In Rowe, Paul S. (ed.). Routledge Handbook of Minorities in the Middle East. Routledge. p. 163. ISBN 978-1-317-23378-7.

- ^ a b Buckley 2002, p. 8.

- ^ Rudolph 2001.

- ^ Aldihisi 2013, p. 188.

- ^ Lupieri 2001, pp. 39–40, 43.

- ^ Gelbert, Carlos (2011). Ginza Rba. Sydney: Living Water Books. ISBN 9780958034630.

- ^ Gelbert, Carlos (2017). The Teachings of the Mandaean John the Baptist. Fairfield, NSW, Australia: Living Water Books. ISBN 9780958034678. OCLC 1000148487.

- ^ Buckley 2002, p. 24.

- ^ Lupieri 2001, p. 116.

- ^ a b Lidzbarski, Mark (1925). Ginzā, der Schatz oder das Grosse buch der Mandäer [Ginzā, the Treasure or the Great Book of the Mandaeans] (in German). Göttingen Vandenhoek & Ruprecht.

- ^ a b Buckley, Jorunn Jacobsen (1 December 2010). The Great Stem of Souls: Reconstructing Mandaean History. Gorgias Press.

- ^ Edwin Yamauchi (1982). "The Mandaeans: Gnostic Survivors". Eerdmans' Handbook to the World's Religions, Lion Publishing, Herts., England, page 110

- ^ "The Ginza Rba – Mandaean Scriptures". The Gnostic Society Library. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- ^ "Welcome to the Mandaean Synod of Australia". Mandaean Synod of Australia. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- ^ History, Mandean union, archived from the original on 17 March 2013

- ^ a b Hachlili, Rachel (1988). Ancient Jewish Art and Archaeology in the Land of Israel. Leiden, The Netherlands: E. J. Brill. p. 101. ISBN 9004081151.

- ^ Gelbert, Carlos (2005). The Mandaeans and the Jews. Edensor Park, NSW: Living Water Books. ISBN 0-9580346-2-1. OCLC 68208613.

- ^ Drower, Ethel Stephana (1959). Canonical Prayerbook of the Mandaeans. Leiden: E. J. Brill.

- ^ Secunda, Shai; Fine, Steven (2012). Shoshannat Yaakov. Brill. p. 345. ISBN 978-90-04-23544-1.

- ^ Mite, Valentinas (14 July 2004). "Iraq: Old Sabaean-Mandean Community is Proud of Its Ancient Faith". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ Holy Spirit University of Kaslik – USEK (27 November 2017). "Open discussion with the Sabaeans Mandaeans". YouTube. Archived from the original on 10 November 2021. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- ^ a b Sly, Liz (16 November 2008). "'This is one of the world's oldest religions, and it is going to die.'". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- ^ Sobhani, Raouf (2009). Mandaean Sabia in Iran. Dar Alboura. p. 128.

- ^ Drower, E. S. (2020). The Secret Adam: A Study of Nasoraean Gnosis. Wipf & Stock Publishers. p. 73. ISBN 978-1532697630.

- ^ Buckley, Jorunn Jacobsen (April 2000). "The Evidence for Women Priests in Mandaeism". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 59 (2): 93–106. doi:10.1086/468798.

- ^ Aldihisi 2013.

- ^ a b Drower 1960b, p. 32.

- ^ Eric Segelberg, "The Ordination of the Mandæan tarmida and its Relation to Jewish and Early Christian Ordination Rites", (Studia Patristica 10, 1970).

- ^ "الريشما ستار جبار حلو رئيس ديانة الصابئة المندائيين". Mandaean Library مكتبة موسوعة العيون المعرفية (in Arabic). Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- ^ "Harmony Day – Liverpool signs declaration on cultural and religious harmony". Liverpool City Champion. 25 March 2019. Archived from the original on 5 November 2021. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- ^ Buckley, Jorunn Jacobsen (1999). "Glimpses of A Life: Yahia Bihram, Mandaean priest". History of Religions. 39: 32–49. doi:10.1086/463572. S2CID 162137462.

- ^ a b Contrera, Russell (8 August 2009). "Saving the people, killing the faith". Holland Sentinel. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015.

- ^ Müller-Kessler, Christa (2004). "The Mandaeans and the Question of Their Origin". ARAM Periodical. 16 (16): 47–60. doi:10.2143/ARAM.16.0.504671.

- ^ Deutsch 1998, p. 78.

- ^ Yamauchi, Edwin (2004). Gnostic Ethics and Mandaean Origins. Gorgias Press. doi:10.31826/9781463209476. ISBN 9781463209476.

- ^ van Bladel 2017; McGrath 2019.

- ^ Nasoraia, Brikha H. S. (2021). The Mandaean gnostic religion: worship practice and deep thought. New Delhi: Sterling. ISBN 978-81-950824-1-4. OCLC 1272858968.

- ^ Drower 1960b, p. xiv; Rudolph 1977, p. 4; Gündüz 1994, pp. vii, 256; Macuch & Drower 1963;[page needed] Segelberg 1969, pp. 228–239; Buckley 2002[page needed]

- ^ McGrath, James F.,"Reading the Story of Miriai on Two Levels: Evidence from Mandaean Anti-Jewish Polemic about the Origins and Setting of Early Mandaeism". ARAM Periodical / (2010): 583–592.

- ^ a b R. Macuch, "Anfänge der Mandäer. Versuch eines geschichtliches Bildes bis zur früh-islamischen Zeit", chap. 6 of F. Altheim and R. Stiehl, Die Araber in der alten Welt II: Bis zur Reichstrennung, Berlin, 1965.

- ^ Häberl, Charles (3 March 2021), "Hebraisms in Mandaic", YouTube, archived from the original on 10 November 2021, retrieved 3 November 2021

- ^ Häberl, Charles (2021). "Mandaic and the Palestinian Question". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 141 (1): 171–184. doi:10.7817/jameroriesoci.141.1.0171. S2CID 234204741.

- ^ Deutsch 1998, p. 78; Thomas 2016

- ^ Mead, G. R. S., Gnostic John the Baptizer: Selections from the Mandaean John-Book, Dumfries & Galloway UK, Anodos Books (2020)

- ^ Zinner, Samuel (2019). The Vines Of Joy: Comparative Studies in Mandaean History and Theology.

- ^ Reeves, J. C., Heralds of that Good Realm: Syro-Mesopotamian Gnostic and Jewish Traditions, Leiden, New York, Koln (1996).

- ^ Quispel, G., Gnosticism and the New Testament, Vigiliae Christianae, vol. 19, No 2. (Jan., 1965), pp. 65–85.

- ^ Beyer, K., The Aramaic Language; Its Distribution and Subdivisions, translated from the German by John F. Healey, Gottingen (1986)

- ^ McGrath, James (19 June 2020). "The Shared Origins of Monotheism, Evil, and Gnosticism". YouTube. Archived from the original on 17 November 2021. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ Thomas 2016.

- ^ Buckley, Jorunn (2012). Lady E. S. Drower's Scholarly Correspondence. Brill. p. 210. ISBN 9789004222472.

- ^ Drower 1960b, p. xv.

- ^ "The Riddle of the Dead Sea Scrolls". YouTube – Discovery Channel documentary. 1990. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ van Bladel 2017, p. 5. On the Sabians generally, see De Blois 1960–2007; De Blois 2004; Fahd 1960–2007; van Bladel 2009.

- ^ Most notably Chwolsohn 1856 and Gündüz 1994, both cited by van Bladel 2009, p. 67.

- ^ As noted by van Bladel 2009, pp. 67–68, modern scholars have variously identified the Sabians of the Quran as Mandaeans, Manichaeans, Sabaeans, Elchasaites, Archontics, ḥunafāʾ (either as a type of Gnostics or as "sectarians"), or as adherents of the astral religion of Harran. These different scholarly identifications are also discussed by Green 1992, pp. 101–120.

- ^ Green 1992, pp. 119–120; Stroumsa 2004, pp. 335–341; Hämeen-Anttila 2006, p. 50; van Bladel 2009, p. 68.

- ^ Buckley 2002, p. 5.

- ^ a b Rudolph, Kurt (7 April 2008). "Mandaeans ii. The Mandaean Religion". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ^ Lidzbarski, Mark, Ginza, der Schatz, oder das Grosse Buch der Mandaer, Leipzig, 1925

- ^ McGrath 2019; Drower 1960b, p. xiv; Rudolph 1977, p. 4; Macuch & Drower 1963;[page needed] Thomas 2016 Lightfoot 1875

- ^ Drower 1960b, p. xiv.

- ^ The Panarion of Epiphanius of Salamis, Book I (Sects 1–46) Frank Williams, translator, 1987 (E.J. Brill, Leiden) ISBN 90-04-07926-2

- ^ a b Kohler, Kaufmann; Ginzberg, Louis. "Elcesaites". Jewish Encyclopedia. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ "Elkesaite | Jewish sect". Britannica. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ Lightfoot 1875.

- ^ Epiphanius of Salamis (1987–2009) [c. 378]. "18. Epiphanius Against the Nasaraeans". Panarion. Vol. 1. Translated by Williams, Frank. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ Saint Epiphanius (Bishop of Constantia Cyprus) (2009). The Panarion of Epiphanius of Salamis: Book I (sects 1–46). Brill. p. 32. ISBN 978-90-04-17017-9.

- ^ Rudolph 1977, p. 5.

- ^ Rudolph 1964, pp. 552–553.

- ^ Rudolph 1964, pp. 552–553; Aldihisi 2013, p. 18

- ^ Coughenour, Robert A. (December 1982). "The Wisdom Stance of Enoch's Redactor". Journal for the Study of Judaism in the Persian, Hellenistic, and Roman Period. 13 (1/2). Brill: 47–55. doi:10.1163/157006382X00035.

- ^ "The War of the Sons of Light Against the Sons of Darkness". Britannica. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ "St. John the Baptist – Possible relationship with the Essenes | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 12 April 2022.

- ^ Newman, Hillel (2006). Proximity to Power and Jewish Sectarian Groups of the Ancient Period. Koninklijke Brill NV. ISBN 9789047408352.

- ^ Hamidović, David (2010). "About the Links between the Dead Sea Scrolls and Mandaean Liturgy". ARAM Periodical. 22: 441–451. doi:10.2143/ARAM.22.0.2131048.

- ^ Dorff, Elliot N.; Rossett, Arthur (1 February 2012). Living Tree, A: The Roots and Growth of Jewish Law. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-1-4384-0142-3.

- ^ a b Stuckenbruck, Loren T.; Gurtner, Daniel M. (26 December 2019). T&T Clark Encyclopedia of Second Temple Judaism Volume Two. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-567-66095-4.

- ^ a b c "Minor Sects". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 12 April 2022.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 257.

- ^ Kohler, Kaufmann. "Hemerobaptists". Jewish Encyclopedia. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- ^ Hastings, James (1957). Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics. Scribner.

- ^ a b Deutsch, Nathaniel (1999–2000). "The Date Palm and the Wellspring:Mandaeism and Jewish Mysticism" (PDF). ARAM. 11 (2): 209–223. doi:10.2143/ARAM.11.2.504462.

- ^ Vinklat, Marek (January 2012). "Jewish Elements in the Mandaic Written Magic". Biernot, D. – Blažek, J. – Veverková, K. (Eds.), "Šalom: Pocta Bedřichu Noskovi K Sedmdesátým Narozeninám" (Deus et Gentes, Vol. 37), Chomutov: L. Marek, 2012. Isbn 978-80-87127-56-8. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- ^ Torgny Säve-Söderbergh, Studies in the Coptic Manichaean Psalm-book, Uppsala, 1949

- ^ Băncilă, Ionuţ (2018). Die mandäische Religion und der aramäische Hintergrund des Manichäismus: Forschungsgeschichte, Textvergleiche, historisch-geographische Verortung (in German). Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-11002-0. OCLC 1043707818.

- ^ a b c Magris 2005, p. 3515.

- ^ Hippolytus, Philosophumena, iv. 51, vi. 20.

- ^ Kurt Rudolph, "Coptica-Mandaica, Zu einigen Übereinstimmungen zwischen Koptisch-Gnostischen und Mandäischen Texten," in Essays on the Nag Hammadi Texts in Honour of Pahor Labib, ed. M. Krause, Leiden: Brill, 1975 191–216. (re-published in Gnosis und Spätantike Religionsgeschichte: Gesämmelte Aufsätze, Leiden; Brill, 1996. [433–457]).

- ^ Pearson, Birger A. (14 July 2011). "Baptism in Sethian Gnostic Texts". Ablution, Initiation, and Baptism. De Gruyter. pp. 119–144. doi:10.1515/9783110247534.119. ISBN 978-3-11-024751-0.

- ^ Buckley, Jorunn Jacobsen (2010). "Mandaean-Sethian Connections". ARAM Periodical. Vol. 22. Peeters Online Journals. pp. 495–507. doi:10.2143/ARAM.22.0.2131051.

- ^ Ersan, Mohammad (2 February 2018). "Are Iraqi Mandaeans better off in Jordan?". Al-Monitor. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ^ Al-Sheati, Ahmed (6 December 2011). "Iran Mandaeans in exile following persecution". Al Arabiya News. Archived from the original on 31 July 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- ^ Hegarty, Siobhan (21 July 2017). "Meet the Mandaeans: Australian followers of John the Baptist celebrate new year". ABC News. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ "Mandaean Faith Lives on in Iranian South". European Country of Origin Information Network – IWPR – Institute for War and Peace Reporting. 30 July 2010. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ MacQuarrie, Brian (13 August 2016). "Embraced by Worcester, Iraq's persecuted Mandaean refugees now seek 'anchor'—their own temple". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

Bibliography

[edit]Primary sources

[edit]- Buckley, Jorunn J. (1993). The Scroll of Exalted Kingship: Diwan Malkuta 'Laita (Mandean Manuscript No. 34 in the Drower Collection, Bodleian Library, Oxford). New Haven: American Oriental Society.

- Drower, Ethel Stephana (1950a). Diwan Abatur, or Progress Through the Purgatories: Text with Translation Notes and Appendices. Città del Vaticano: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana.

- Drower, Ethel Stephana (1950b). Šarḥ ḏ Qabin ḏ šišlam Rba (D. C. 38). Explanatory Commentary on the Marriage-Ceremony of the great Šišlam. Roma: Pontificio Istituto Biblico.

- Drower, Ethel Stephana (1960a). The Thousand and Twelve Questions (Alf trisar šuialia). Berlin: Akademie-Verlag.

- Drower, Ethel Stephana (1962). The Coronation of the Great Šišlam, Being a Description of the Rite of the Coronation of a Mandaean Priest according to the Ancient Canon. Leiden: Brill.

- Drower, Ethel Stephana (1963). A Pair of Naṣoraean Commentaries (Two Priestly Documents): The Great First World and The Lesser First World. Leiden: Brill.

- Häberl, Charles G. (2022). The Book of Kings and the Explanations of This World: A Universal History from the Late Sasanian Empire. Translated Texts for Historians. Vol. 80. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-1-800-85627-1.

- Häberl, Charles G.; McGrath, James F., eds. (2019). The Mandaean Book of John. Critical Edition, Translation, and Commentary. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110487862. ISBN 9783110487862. S2CID 226656912.

- Häberl, Charles G.; McGrath, James F., eds. (2020). The Mandaean Book of John: Text and Translation. Berlin: De Gruyter. pp. vii–222. doi:10.1515/9783110487862. ISBN 9783110487862. S2CID 226656912. (open access version of text and translation, taken from Häberl & McGrath 2019)

Secondary sources

[edit]- Aldihisi, Sabah (2013). The Story of Creation in the Mandaean Holy Book the Ginza Rabba (PDF). ProQuest LLC. OCLC 1063456888.

- Αριστοτέλειο Πανεπιστήμιο Θεσσαλονίκης; Κέντρο Βυζαντινών Ερευνών (2010). Βυζαντινα (in Greek).

- Buckley, Jorunn J. (2002). The Mandaeans: Ancient Texts and Modern People. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Buckley, Jorunn J. (2005). The Great Stem of Souls: Reconstruction Mandaean History. Piscataway: Gorgias Press.

- Chwolsohn, Daniel (1856). Die Ssabier und die Ssabismus [The Sabians and the Sabianism]. Vols. 1–2. (in German). St. Petersburg: Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften. OCLC 64850836.

- Deutsch, Nathaniel (1995). The Gnostic Imagination: Gnosticism, Mandaeism and Merkabah Mysticism. Brill. ISBN 9789004672505.

- Deutsch, Nathaniel (1998). Guardians of the Gate-Angelic Vice Regency in Late Antiquity. Brill.

- Deutsch, Nathaniel (1999). Guardians of the Gate: Angelic Vice-regency in the Late Antiquity. Brill. ISBN 9789004679245.

- Dodd, C. H. (1968). "Mandaism". The Interpretation of the Fourth Gospel. Cambridge University Press.

- Drower, Ethel Stephana (1937). The Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran: Their Cults, Customs, Magic Legends, and Folklore. Oxford: Clarendon Press. (reprint: Piscataway: Gorgias Press, 2002)

- Drower, Ethel Stephana (1960b). The Secret Adam: A Study of Nasoraean Gnosis. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 654318531.

- Gaster, Moses (1925). The Samaritans: Their History, Doctrines and Literature (PDF). London: Oxford University Press.

- Green, Tamara M. (1992). The City of the Moon God: Religious Traditions of Harran. Religions in the Graeco-Roman World. Vol. 114. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-09513-7.

- Gündüz, Şinasi [in Turkish] (1994). The Knowledge of Life: The Origins and Early History of the Mandaeans and Their Relation to the Sabians of the Qur'ān and to the Harranians. Journal of Semitic Studies Supplement. Vol. 3. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199221936.

- Hämeen-Anttila, Jaakko (2006). The Last Pagans of Iraq: Ibn Waḥshiyya and His Nabatean Agriculture. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-15010-2.

- Higgins, Godfrey (1836). Anacalypsis.

- Hirschfeld, Hartwig (1898). The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland.

- Hoffmann, Andres Gottlieb; Merx, Adalbert (1867). Grammatica syriaca (in Latin). Vol. I. Halle: Verlag der Buchhandlung des Weisenhauses.

- Lightfoot, Joseph Barber (1875). "On Some Points Connected with the Essenes". St. Paul's epistles to the Colossians and to Philemon: a revised text with introductions, notes, and dissertations. London: Macmillan Publishers. OCLC 6150927.

- Lupieri, Edmondo (2001). The Mandaeans: The Last Gnostics. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans.

- Macuch, Rudolf; Drower, E. S. (1963). A Mandaic Dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Petermann, J. Heinrich (2007). The Great Treasure of the Mandaeans. Piscataway: Gorgias Press. (reprint of Thesaurus s. Liber Magni)

- Rudolph, Kurt (April 1964). "War Der Verfasser Der Oden Salomos Ein "Qumran-Christ"? Ein Beitrag zur Diskussion um die Anfänge der Gnosis" [Was the author of the Odes of Solomon a "Qumran Christian"? A contribution to the discussion about the beginnings of Gnosis]. Revue de Qumrân (in German). 4 (16). Peeters: 523–555.

- Rudolph, Kurt (1977). "Mandaeism". In Moore, Albert C. (ed.). Iconography of Religions: An Introduction. Vol. 21. Chris Robertson. ISBN 9780800604882.

- Rudolph, Kurt (2001). Gnosis: The Nature and History of Gnosticism. A&C Black. pp. 343–366. ISBN 9780567086402.

- Segelberg, Eric (1958). Maşbūtā. Studies in the Ritual of the Mandæan Baptism. Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksells.

- Segelberg, Eric (1969). "Old and New Testament figures in Mandaean version". Scripta Instituti Donneriani Aboensis. 3: 228–239. doi:10.30674/scripta.67040.

- Segelberg, Eric (1970). "The Ordination of the Mandæan tarmida and its Relation to Jewish and Early Christian Ordination Rites". Studia Patristica. 10.

- Segelberg, Eric (1976). Trāşa d-Tāga d-Śiślām Rabba. Studies in the rite called the Coronation of Śiślām Rabba. i: Zur Sprache und Literatur der Mandäer. Studia Mandaica. Vol. 1. Berlin & New York: Walter de Gruyter.

- Segelberg, Eric (1977). "Zidqa Brika and the Mandæan Problem". In Widengren, Geo; Hellholm, David (eds.). Proceedings of the International Colloquium on Gnosticism. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell.

- Segelberg, Eric (1978). "The pihta and mambuha Prayers. To the Question of the Liturgical Development amnong the Mandæans". Gnosis. Festschrift für Hans Jonas. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Segelberg, Eric (1990). "Mandæan – Jewish – Christian. How does the Mandæan tradition relate to Jewish and Christian tradition?". Gnostica Madaica Liturgica. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Historia Religionum. Vol. 11. Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksell.

- Stroumsa, Sarah (2004). "Sabéens de Ḥarrān et Sabéens de Maïmonide". In Lévy, Tony; Rashed, Roshdi (eds.). Maïmonide: Philosophe et savant (1138–1204). Leuven: Peeters. pp. 335–352. ISBN 9789042914582.

- Thomas, Richard (29 January 2016). "The Israelite Origins of the Mandaean People". Studia Antiqua. 5 (2).

- van Bladel, Kevin (2009). "Hermes and the Ṣābians of Ḥarrān". The Arabic Hermes: From Pagan Sage to Prophet of Science. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 64–118. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195376135.003.0003. ISBN 978-0-19-537613-5.

- van Bladel, Kevin (2017). From Sasanian Mandaeans to Ṣābians of the Marshes. Leiden: Brill. doi:10.1163/9789004339460. ISBN 978-90-04-33943-9.

- Review: McGrath, James F. (2019). "James F. McGrath Reviews From Sasanian Mandaeans to Sabians (van Bladel)". Enoch Seminar Online. Archived from the original on 9 December 2023. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- Wright, William (1871). Apocryphal Acts of the Apostles. Vol. 2.

- Yamauchi, Edwin M. (2005) [1967]. Mandaic Incantation Texts. Piscataway: Gorgias Press.

- Yamauchi, Edwin M. (2004) [1970]. Gnostic Ethics and Mandaean Origins. Piscataway: Gorgias Press.

- Häberl, Charles G. (2009), The neo-Mandaic dialect of Khorramshahr, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3-447-05874-2

Tertiary sources

[edit]- Buckley, Jorunn J. (2012). "Mandaeans iv. Community in Iran". Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition.

- De Blois, F.C. (1960–2007). "Ṣābiʾ". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0952.

- De Blois, François (2004). "Sabians". In McAuliffe, Jane Dammen (ed.). Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān. doi:10.1163/1875-3922_q3_EQSIM_00362.

- Fahd, Toufic (1960–2007). "Ṣābiʾa". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0953.

- Magris, Aldo (2005). "Gnosticism: Gnosticism from its origins to the Middle Ages (further considerations)". In Jones, Lindsay (ed.). Macmillan Encyclopedia of Religion (2nd ed.). New York: Macmillan Inc. pp. 3515–3516. ISBN 978-0028657332. OCLC 56057973.

External links

[edit]This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (February 2024) |

- Mandaean Association Union – The Mandaean Association Union is an international federation which strives for unification of Mandaeans around the globe. Information in English and Arabic.

- BBC: Iraq chaos threatens ancient faith

- BBC: Mandaeans – a threatened religion

- Shahāb Mirzā'i, Ablution of Mandaeans (Ghosl-e Sābe'in – غسل صابئين), in Persian, Jadid Online, 18 December 2008

- Audio slideshow (showing Iranian Mandaeans performing ablution on the banks of the Karun river in Ahvaz): (4 min 25 sec)

- The Worlds of Mandaean Priests, University of Exeter

Mandaean scriptures

[edit]- Mandaean scriptures: Qolastā and Haran Gawaitha texts and fragments (note that the book titled Ginza Rabba is not the Ginza Rabba but is instead Qolastā, "The Canonical Prayerbook of the Mandaeans" as translated by E.S Drower).

- The Ginza Rabba (1925 German translation by Mark Lidzbarski) at the Internet Archive

- The John-Book (Draša D-Iahia) – complete text in Mandaic and German translation (1905) by Mark Lidzbarski at the Internet Archive

- Mandaic liturgies – Mandaic text (in Hebrew transliteration) and German translation (1925) by Mark Lidzbarski at the Internet Archive

- Mandaean scriptures at the Mandaean Network's site

Books about Mandaeism available online

[edit]- Extracts from E. S. Drower, Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran, Leiden, 1962

- The Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran by Lady Drower, 1937 – the entire book

Mandaeism

View on GrokipediaTerminology

Etymology

The term Mandaean originates from the Mandaic Aramaic word mandā (ࡌࡀࡍࡃࡀ), denoting "knowledge" or "gnosis," reflecting the religion's core emphasis on salvific, esoteric understanding as a path to spiritual enlightenment. This etymon underlies the self-appellation mandāyā (ࡌࡀࡍࡃࡀࡉࡉࡀ), meaning "those who possess knowledge" or "gnostics," which distinguishes adherents from other groups and highlights their doctrinal prioritization of manda over ritual alone.[8][5] "Mandaeism," as the designation for the religion, is a modern scholarly construct derived directly from this ethnonym, gaining prominence in Western orientalist studies after 19th-century documentation of Mandaean texts and communities in southern Iraq and Iran. Mandaeans themselves more commonly use terms like Nasōrāyā (ࡍࡀࡎࡅࡓࡀࡉࡉࡀ), from the root nsr implying "observers" or "guardians" of divine secrets, underscoring a preferred internal focus on custodial knowledge transmission rather than the externally imposed "gnostic" label.[8]Alternative Designations

Mandaeans designate themselves primarily as Naṣorayyā (Nasoraeans), a term derived from their scriptures emphasizing possessors of manda (knowledge) of salvific truths, used more frequently than "Mandaean" in religious texts.[9] This self-appellation reflects an initiatory elite status within the community, though applied broadly to adherents.[9] In Islamic historical and legal contexts, Mandaeans have been termed Ṣābeʾin (Sabians), linking them to the Quranic Sabians afforded protected status as Ahl al-Kitāb (People of the Book), based on shared baptismal rites and monotheistic practices.[9] Modern Iraqi and Iranian communities are officially recognized as Sabian-Mandaeans, distinguishing them from the pagan Sabians of Harran who adopted the name for exemption from jizya tax under early caliphates.[10] The designation "Sabian" etymologically connects to Mandaic saba, denoting immersion or baptism, central to Mandaean ritual.[10] European scholars in the 19th and early 20th centuries occasionally referred to Mandaeism as "disciples of John" or the "religion of John the Baptist," highlighting its veneration of Yahya (John) as a chief prophet while rejecting Jesus and Mosaic law.[8] These terms underscore doctrinal distinctions but are less used today amid Mandaean diaspora emphasis on indigenous Mesopotamian roots.[9]Origins and Antiquity

Debates on Geographical and Temporal Origins