Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Audio game

View on Wikipedia| Video games |

|---|

An audio game is an electronic game played on a device such as a personal computer. It is similar to a video game save that there is audible and tactile feedback but not visual.

Audio games originally started out as 'blind accessible'-games and were developed mostly by amateurs and blind programmers.[1] But more and more people are showing interest in audio games, ranging from sound artists, game accessibility researchers, mobile game developers and mainstream video gamers. Most audio games run on a personal computer platform, although there are a few audio games for handhelds and video game consoles. Audio games feature the same variety of genres as video games, such as adventure games, racing games, etc.[2]

Audio game history

[edit]The term "electronic game" is commonly understood as a synonym for the narrower concept of the "video game." This is understandable as both electronic games and video games have developed in parallel and the game market has always had a strong bias toward the visual. The first electronic game, in fact, is often cited to be Cathode-Ray Tube Amusement Device (1947) a decidedly visual game. Despite the difficulties in creating a visual component to early electronic games imposed by crude graphics, small view-screens, and power consumption, video games remained the primary focus of the early electronic game market.

Arcade and one-off handheld audio games – the early years

[edit]

Atari released the first audio game, Touch Me, in 1974. Housed in an arcade cabinet, Touch Me featured a series of lights which would flash with an accompanying tone. The player would reproduce the sequence by pressing a corresponding sequence of buttons and then the game would add another light/sound to the end of the growing sequence to continually test the player's eidetic memory in a Pelmanism-style format. Although the game featured both a visual and an auditory component, the disconnect between the two enabled both the seeing and the visually impaired to equally enjoy the game.

Based on the popularity of Touch Me, in 1978 Milton Bradley Company released a handheld audio game entitled Simon at Studio 54 in New York City. Whereas Touch Me had been in competition with other visual-centric video games and consequently remained only a minor success, the allure of a personal electronic game allowed Simon to capture a much greater share of the market. Simon became an immediate success eventually becoming a pop culture symbol of the 1980s.

In the decades following the release of Simon, numerous clones and variations were produced including Merlin among others. Beginning in 1996, Milton Bradley and a number of other producers released the handheld Bop It which featured a similar concept of a growing series of commands designed to test eidetic memory.[3] Other related games soon followed including Bop It Extreme (1998),[4] Bop It-Extreme 2 (2002–2003), Zing-It, Top-It, and Loopz (2010)[5]

TTS software and the PC – the second wave

[edit]

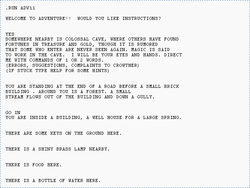

Before graphical operating systems like Windows, most home computers used text-based operating systems such as DOS. Being text-based meant that they were relatively accessible to visually impaired users, requiring only the additional use of text-to-speech (TTS) software. For the same reason, following the development of TTS software, text-based games such as early text-only works of interactive fiction were also equally accessible to users with or without a visual impairment.[6] Since the availability of such software was not commonly accessible until the inclusion of the MacInTalk program on Apple Computers in 1984, the library of games which became accessible to the vision impaired spanned everything from the earliest text adventure, Colossal Cave Adventure (1976), to the comparatively advanced works of interactive fiction which had developed in the subsequent 8 years. Although the popularity of this genre has waned in the general market as video-centric games became the dominant form of electronic game, this library is still growing with the freeware development by devoted enthusiasts of new interactive fiction titles each year.[6]

Accessibility for the visually impaired began to change, some time prior to the advent of graphical operating systems as computers became powerful enough to support more video-centric games. This created a gap between electronic games for the seeing and games for the blind — a gap that has by now grown substantially. Due to a strong market bias in favor of the seeing, electronic games were primarily developed for this demographic. While seeing gamers could venture into 3D gaming worlds in such video game titles as Myst, Final Fantasy and Doom, blind gamers were relegated to playing more mundane games such as Blackjack, or Battleship.

As video games flourished and became increasingly common, however, amateur game designers began to adapt video games for the blind via sound. In time audio game programmers began to develop audio-only games, based to a smaller and smaller degree on existing video game ideas and instead focusing on the possibilities of game immersion and feedback with sound. Specifically, three-dimensional positional audio (binaural recording) has been developed since 2000 and now figures prominently in, for example, such audio games as BBBeat. To effect this, a sound is played in the left, center, or right channel to indicate an object's position in a virtual gaming environment. Generally, this involves stereo panning of various sound effects, many of which are looped to serve as indicators of hazards or objects with which the user can interact. Volume also plays a major role in 3D audio games primarily to indicate an object's proximity with reference to the user. The pitch of a sound is often varied to convey other information about the object it symbolizes. Voice talent is used to indicate menu items rather than text. These parameters have allowed for the creation of, among other genres, side scrollers, 3D action adventures, shooters, and arcade style games.

The website Audiogames.net provides a list of audio games and a forum for the community of audio game developers and gamers. Many of the listed games contain some primitive graphics as to make audio games not only accessible to blind and visually impaired people but also to gamers with vision, who may be unexperienced with TTS, auditory menus and typical keyboard mappings. Examples include Shades of Doom and the CURAT Sonification game.

Console audio games and the modern era

[edit]Most audio games are now developed by several small companies (consisting of only a team of one to four people). The main audience remains primarily visually impaired users, however the game market at large is gradually taking more notice of audio games as well due to the issue of game accessibility. Commercial interest in audio games has steadily grown and as a result artists and students have created a number of experimental freeware PC audio games to explore the possibilities and limitations of this gaming form.

Despite the increase in interest in audio games, however, many modern games still lack sufficient audio cues to be considered fully accessible for the visually impaired. Furthermore, the industry still lacks a clear set of accessibility guidelines for their development.[7] Tools such as the once popular Blastbay Game Toolkit engine that aided in the development of audio games are now obsolete, but current game engines like Unity and Unreal that can support audio game development are not specifically designed for doing so, creating an additional hurdle for audio game developers.[8]

In the field of console gaming, there has been very little in the way of audio games. One notable exception are the strong audio elements present in several of the games produced by the Japanese video game developer Warp, founded by musician and designer Kenji Eno. In 1996, the company released Enemy Zero, which was notable for the fact that most of its enemies are invisible, with the player needing to rely on an audio-based tracking system, wherein the frequency and pitch of a beeping sound is used to locate them in 3D space.[9] A year later, Warp released Real Sound: Kaze no Regret, an adventure audio game. Structured similarly to a visual novel, the game was designed to provide equal access to sighted and blind players, and as such features no visuals at all during gameplay, consisting purely of voice acting, sound effects, and music.

Discussing Real Sound's production, Eno stated:

I got tired of [CG graphics]. I didn't want people to think that they could predict what Warp would do next. Also, I had a chance to visit people who are visually disabled, and I learned that there are blind people who play action games. Of course, they're not able to have the full experience, and they're kind of trying to force themselves to be able to play, but they're making the effort. So I thought that if you turn off the monitor, both of you are just hearing the game. So after you finish the game, you can have an equal conversation about it with a blind person. That's an inspiration behind this game as well.[10]

Audio-based gameplay elements are also present in Warp's D2.[11]

Nintendo, as part of its shift to alternative gameplay forms, has shown recent interest in audio games through its own development teams.[12] In July 2006, Nintendo released a collection of audio games called Soundvoyager as the newest member of its spare Digiluxe series. The Digiluxe series for Game Boy Advance consists of 7 games (in 2 series) that are characterized by simple yet compelling gameplay,[13] minimal graphics, and the emphasis, in such titles as Soundvoyager and Dotstream, on music. Soundvoyager contains 7 audio games (Sound Slalom, Sound Picker, Sound Drive, Sound Cock, Sound Chase, Sound Catcher, and Sound Cannon).[14] The Digiluxe series has been available in Japan since July 2006.[15]

In 2008, MIT students collaborated with the government of Singapore and a professor at the National University of Singapore to create AudiOdyssey, a game which allows both blind and sighted gamers to play together.[16]

Apple's iPhone platform has become home to a number of audio games, including Papa Sangre.[17] Other examples include Audiogame.it's Flarestar (a space-themed exploration game that features combat against training drones and other spacecraft)[7] and Sonic Tennis (a game which simulates a tennis match and features a multiplayer mode).[18]

Android devices also feature a myriad of audio games. For example, the studio Blind Faith Games has developed various games for Android with the goal of accessibility for the visually impaired community.[19] Examples include Golf Accessible (a simulation of golfing) and Zarodnik (a strategy game where the user faces a monster in the depths of the ocean), which utilize screen vibrations and audio cues for the gameplay experience.[19][7] Another unique example of an audio game for Android is a game currently in development by researchers at Tsinghua University titled Wander, which is intended to be used as the player falls asleep to improve the quality of their rest. A guide provides the instructions to users verbally, and they use their breath to explore a forest filled with relaxing environmental noises.[20]

With the rise in popularity of voice assistants such as Amazon Alexa came a new set of audio games. As of June 2021, 10,000 audio games were available as Alexa Skills for use with Amazon Alexa.[21] Among them are games like Rain Labs' Animal Sounds, which asks users to correctly identify the noises made by various animals.[22]

TTS-enabling video games

[edit]The rise of text-to-speech (TTS) software and steady improvements in the field have allowed full audio-conversion of traditionally video-based games. Such games were intended for use by and marketed to the seeing, however they do not actually rest primarily on the visual aspects of the game and so members of the audio game community have been able to convert them to audio games by using them in conjunction with TTS software. While this was originally only available for strictly text-based games like text adventures and MUDs, advances in TTS software have led to increased functionality with a diverse array of software types beyond text-only media allowing other works of interactive fiction as well as various simulator games to be enjoyed in a strictly audio environment.

Examples of such games include:

- A Dark Room – (Doublespeak Games, 2013)

- Hattrick – (ExtraLives AB, 1997)[23]

- OGame – (Gameforge, 2002)[24]

- Jennifer Government: NationStates – (Max Barry, 2002)[25]

- Grendel's Cave – (Grendel Enterprises, 1998)[26]

Another example is The Last of Us Part II, which was released by Naughty Dog in the summer of 2020 for the PlayStation 4. The game contains over 60 accessibility features, including a text-to-speech feature.[27] Other features that make the game completely playable without sight include the use of voice actors, haptic feedback, and audio cues that act as hints to the player.[27] In addition, the game provides the common audio game feature of a sound glossary menu. On this menu, the user can scroll through a variety of audio cues and hear what they sound like and what they are used for during gameplay. For this game in particular, examples include signals to the user that they can crouch, jump, or interact with the nearby environment.[27]

See also

[edit]- Binaural recording

- Dummy head recording

- Holophonics

- Interactive fiction

- List of gaming topics

- Music video game

- Video game genres

- Video game music

- IEZA Framework – a framework for conceptual game sound design

References

[edit]- ^ Rovithis, Emmanouel (2012). "A Classification of Audio-Based Games in terms of Sonic Gameplay and the introduction of the Audio-Role-Playing-Game: Kronos". Proceedings of the 7th Audio Mostly Conference: A Conference on Interaction with Sound. Corfu, Greece: ACM New York, NY, USA. pp. 160–164. doi:10.1145/2371456.2371483.

- ^ Rovithis, Emmanouel; Floros, Andreas; Mniestris, Andreas; Grigoriou, Nikolas (2014). "Audio games as educational tools: Design principles and examples". 2014 IEEE Games Media Entertainment. Toronto, ON: IEEE. pp. 1–8. doi:10.1109/GEM.2014.7048083. ISBN 978-1-4799-7545-7. S2CID 28804427.

- ^ Manneville, Tim (1 September 2004). "Bop-it FAQ". Manneville.com.

- ^ BopIt Extreme rules and assembly instructions from World of Tim (personal website)

- ^ http://www.playloopz.com/ Loopz's Official Website

- ^ a b Damoulakis, Ari (July 29, 2008). "A Blind Man's Take on Interactive Fiction". SPAG. No. 52. pp. 7–9.

- ^ a b c Araújo, Maria C. C.; Façanha, Agebson R.; Darin, Ticianne G. R.; Sánchez, Jaime; Andrade, Rossana M. C.; Viana, Windson (2017), "Mobile Audio Games Accessibility Evaluation for Users Who Are Blind", Universal Access in Human–Computer Interaction. Designing Novel Interactions, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 10278, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 242–259, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-58703-5_18, ISBN 978-3-319-58702-8, retrieved 2023-03-05

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: work parameter with ISBN (link) - ^ Urbanek, Michael; Güldenpfennig, Florian; Habiger, Michael (2019-09-18). "Creating Audio Games Online with a Browser-Based Editor". Proceedings of the 14th International Audio Mostly Conference: A Journey in Sound. New York, NY, USA: ACM. pp. 272–276. doi:10.1145/3356590.3356636. ISBN 9781450372978. S2CID 208947017.

- ^ Fleming, Jeffrey (May 10, 2007). "Game Collector's Melancholy – Kenji Eno". GameSetWatch. Archived from the original on 13 April 2008.

- ^ "Kenji Eno: Reclusive Japanese Game Creator Breaks His Silence". 1UP.com. 2008-08-07. Archived from the original on June 22, 2016.

- ^ "Real Sound - Kaze No Riglet". AudioGames.net game review site.

- ^ "AudioGames, your resource for audiogames, games for the blind, games for the visually impaired!". www.audiogames.net.

- ^ Harris, Craig (June 16, 2012). "Bit Generations". IGN.

- ^ Nintendo (2006-07-27). Soundvoyager (Game Boy Advance) (in Japanese). Nintendo.

- ^ Ltd., Nintendo Co. "bit Generations". www.nintendo.co.jp.

- ^ Ellin, Abby (2008-12-26). "See Me, Hear Me: A Video Game for the Blind". The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-11-14.

- ^ Kirke, Alexis (2018), "When the Soundtrack is the Game: From Audio-Games to Gaming the Music", Emotion in Video Game Soundtracking, International Series on Computer Entertainment and Media Technology, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 65–83, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-72272-6_7, hdl:10026.1/12447, ISBN 978-3-319-72271-9, retrieved 2023-03-05

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: work parameter with ISBN (link) - ^ Baldan, Stefano; de Götzen, Amalia; Serafin, Stefania (2013-04-27). "Mobile rhythmic interaction in a sonic tennis game". CHI '13 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems. New York, NY, USA: ACM. pp. 2903–2906. doi:10.1145/2468356.2479570. ISBN 9781450319522. S2CID 7021479.

- ^ a b "Blind Faith Games (EN)". en.blind-faith-games.e-ucm.es. Retrieved 2023-03-05.

- ^ Cai, Jinghe; Chen, Bohan; Wang, Chen; Jia, Jia (2021-10-15). "Wander: A breath-control Audio Game to Support Sound Sleep". Extended Abstracts of the 2021 Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play. New York, NY, USA: ACM. pp. 17–23. doi:10.1145/3450337.3483461. ISBN 9781450383561. S2CID 238992788.

- ^ Du, Yao; Zhang, Kerri; Ramabadran, Sruthi; Liu, Yusa (2021-06-24). ""Alexa, What is That Sound?" A Video Analysis of Child-Agent Communication from Two Amazon Alexa Games". Interaction Design and Children. New York, NY, USA: ACM. pp. 513–520. doi:10.1145/3459990.3465195. ISBN 9781450384520. S2CID 235628582.

- ^ "Animal Sounds". www.amazon.com. Retrieved 2023-03-05.

- ^ "Hattrick". audiogames.net. 2 February 2022.

- ^ "OGame". audiogames.net. 2 February 2022.

- ^ "Nation States". audiogames.net. 2 February 2022.

- ^ "Grendels cave". audiogames.net. 28 January 2023.

- ^ a b c Leite, Patricia da Silva; Almeida, Leonelo Dell Anhol (2021), Antona, Margherita; Stephanidis, Constantine (eds.), "Extended Analysis Procedure for Inclusive Game Elements: Accessibility Features in the Last of Us Part 2", Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction. Design Methods and User Experience, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 12768, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 166–185, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-78092-0_11, ISBN 978-3-030-78091-3, S2CID 235800200, retrieved 2023-03-24

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: work parameter with ISBN (link)

External links

[edit]- Game Accessibility Project, website of the Game Accessibility project

- PCS Accessible Game developers List, a big list of blind accessible games and audio games

- IGDA Game Accessibility Special Interest Group, working to make mainstream games accessible for all disability groups

- AudioGames.net, community website for audio gamers featuring a game database and a forum

- AudioGames resources, audio game resources and articles

- Accessible Gaming Rending Independence Possible (AGRIP), home of Audio Quake – a project designed to make Quake accessible for visually impaired individuals

- The Virtual Barbershop[permanent dead link], a demonstration of multiple binaural sound effects. (NOTE: This is intended for use with stereo headphones)

- Audio only menus, Some recommendations for the design of audio only menus for audio games.