Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Video game development

View on Wikipedia| Part of a series on the |

| Video game industry |

|---|

Video game development (sometimes shortened to gamedev) is the process of creating a video game. It is a multidisciplinary practice, involving programming, design, art, audio, user interface, and writing. Each of those may be made up of more specialized skills; art includes 3D modeling of objects, character modeling, animation, visual effects, and so on. Development is supported by project management, production, and quality assurance. Teams can be many hundreds of people, a small group, or even a single person.

Development of commercial video games is normally funded by a publisher and can take two to five years to reach completion. Game creation by small, self-funded teams is called independent development. The technology in a game may be written from scratch or use proprietary software specific to one company. As development has become more complex, it has become common for companies and independent developers alike to use off-the-shelf "engines" such as Unity, Unreal Engine or Godot.[1][2]

Commercial game development began in the 1970s with the advent of arcade video games, first-generation video game consoles like the Atari 2600, and home computers like the Apple II. Into the 1980s, a lone programmer could develop a full and complete game such as Pitfall!. By the second and third generation of video game consoles in the late 1980s, the growing popularity of 3D graphics on personal computers, and higher expectations for visuals and quality, it became difficult for a single person to produce a mainstream video game. The average cost of producing a high-end (often called AAA) game slowly rose from US$1–4 million in 2000, to over $200 million and up by 2023. At the same time, independent game development has flourished. The best-selling video game of all time, Minecraft, was initially written by one person, then supported by a small team, before the company was acquired by Microsoft and greatly expanded.

Mainstream commercial video games are generally developed in phases. A concept is developed which then moves to pre-production where prototypes are written and the plan for the entire game is created. This is followed by full-scale development or production, then sometimes a post-production period where the game is polished. It has become common for many developers, especially smaller developers, to publicly release games in an "early access" form, where iterative development takes place in tandem with feedback from actual players.

Overview

[edit]Games are produced through the software development process.[3] They are created both as a form of artistic expression[4] and a commercial product intended to generate profit.[5] Game development is often described as a blend of art and science,[6] reflecting the technical precision and creative design required.[7] Development is normally funded by a publisher,[8] and careful budget estimation is critical to success.[9] Poor planning may cause projects to exceed budgets or fail to meet expectations.[10] In fact, the majority of commercial games do not produce profit.[11][12][13] Most developers therefore plan their production schedule carefully to balance creative goals with available resources.[14]

The game industry requires innovations, as publishers cannot profit from the constant release of repetitive sequels and imitations.[15][neutrality is disputed] Every year new independent development companies open and some manage to develop hit titles. Similarly, many developers close down because they cannot find a publishing contract or their production is not profitable.[16] It is difficult to start a new company due to the high initial investment required.[17] Nevertheless, the growth of the casual and mobile game market has allowed developers with smaller teams to enter the market. Once the companies become financially stable, they may expand to develop larger games.[16] Most developers start small and gradually expand their business.[17] A developer receiving profit from a successful title may store up capital to expand and re-factor their company, as well as tolerate more failed deadlines.[18]

An average development budget for a multiplatform game is US$18-28M, with high-profile games often exceeding $40M.[19]

In the early era of home computers and video game consoles in the early 1980s, a single programmer could handle almost all the tasks of developing a game — programming, graphical design, sound effects, etc.[20][21][22] It could take as little as six weeks to develop a game.[21] However, the high user expectations and requirements[21] of modern commercial games far exceed the capabilities of a single developer and require the splitting of responsibilities.[23] A team of over a hundred people can be employed full-time for a single project.[22]

Game development, production, or design is a process that starts from an idea or concept.[24][25][26][27] Often the idea is based on a modification of an existing game concept.[24][28] The game idea may fall within one or several genres.[29] Designers often experiment with different combinations of genres.[29][30] A game designer generally writes an initial game proposal document, that describes the basic concept, gameplay, feature list, setting and story, target audience, requirements and schedule, and finally staff and budget estimates.[31] Different companies have different formal procedures and philosophies regarding game design and development.[32][32][33] There is no standardized development method; however commonalities exist.[33][34]

A game developer may range from a single individual to a large multinational company. There are both independent and publisher-owned studios.[35] Independent developers rely on financial support from a game publisher.[36] They usually have to develop a game from concept to prototype without external funding. The formal game proposal is then submitted to publishers, who may finance the game development from several months to years. The publisher would retain exclusive rights to distribute and market the game and would often own the intellectual property rights for the game franchise.[35] The publisher may also own the development studio,[35][37] or it may have internal development studio(s). Generally the publisher is the one who owns the game's intellectual property rights.[12]

Many larger development companies work on several titles at once. This is necessary because of the time taken between shipping a game and receiving royalty payments, which may be between 6 and 18 months. Small companies may structure contracts, ask for advances on royalties, use shareware distribution, employ part-time workers and use other methods to meet payroll demands.[38]

Console manufacturers, such as Microsoft, Nintendo, or Sony, have a standard set of technical requirements that a game must conform to in order to be approved. Additionally, the game concept must be approved by the manufacturer, who may refuse to approve certain titles.[39]

Most modern PC or console games take from three to five years to complete[citation needed], whereas a mobile game can be developed in a few months.[40] The length of development is influenced by a number of factors, such as genre, scale, development platform and number of assets.[citation needed]

Some games can take much longer than the average time frame to complete. An infamous example is 3D Realms' Duke Nukem Forever, announced to be in production in April 1997 and released fourteen years later in June 2011.[41] Planning for Maxis' game Spore began in late 1999; the game was released nine years later in September 2008.[citation needed] The game Prey was briefly profiled in a 1997 issue of PC Gamer, but was not released until 2006, and only then in highly altered form. Finally, Team Fortress 2 was in development from 1998 until its 2007 release, and emerged from a convoluted development process involving "probably three or four different games", according to Gabe Newell.[42]

The game revenue from retail is divided among the parties along the distribution chain, such as — developer, publisher, retail, manufacturer and console royalty. Many developers fail to profit from this and go bankrupt.[38] Many seek alternative economic models through Internet marketing and distribution channels to improve returns,[43] as through a mobile distribution channel the share of a developer can be up to 70% of the total revenue[40] and through an online distribution channel owned by the developer almost 100%.[citation needed]

History

[edit]

The history of game making begins with the development of the first video games, although which video game is the first depends on the definition of video game. The first games created had little entertainment value, and their development focus was separate from user experience—in fact, these games required mainframe computers to play them.[44] OXO, written by Alexander S. Douglas in 1952, was the first computer game to use a digital display.[23] In 1958, a game called Tennis for Two, which displayed its output on an oscilloscope, was made by Willy Higinbotham, a physicist working at the Brookhaven National Laboratory.[45][46] In 1961, a mainframe computer game called Spacewar! was developed by a group of Massachusetts Institute of Technology students led by Steve Russell.[45]

True commercial design and development of games began in the 1970s, when arcade video games and first-generation consoles were marketed. In 1971, Computer Space was the first commercially sold, coin-operated video game. It used a black-and-white television for its display, and the computer system was made of 74 series TTL chips.[47] In 1972, the first home console system was released called Magnavox Odyssey, developed by Ralph H. Baer.[48] That same year, Atari released Pong, an arcade game that increased video game popularity.[49] The commercial success of Pong led other companies to develop Pong clones, spawning the video game industry.[50]

Programmers worked within the big companies to produce games for these devices. The industry did not see huge innovation in game design and a large number of consoles had very similar games.[51] Many of these early games were often Pong clones.[52] Some games were different, however, such as Gun Fight, which was significant for several reasons:[53] an early 1975 on-foot, multi-directional shooter,[54] which depicted game characters,[55] game violence, and human-to-human combat.[56] Tomohiro Nishikado's original version was based on discrete logic,[57] which Dave Nutting adapted using the Intel 8080, making it the first video game to use a microprocessor.[58] Console manufacturers soon started to produce consoles that were able to play independently developed games,[59] and ran on microprocessors, marking the beginning of second-generation consoles, beginning with the release of the Fairchild Channel F in 1976.[citation needed]

The flood of Pong clones led to the video game crash of 1977, which eventually came to an end with the mainstream success of Taito's 1978 arcade shooter game Space Invaders,[52] marking the beginning of the golden age of arcade video games and inspiring dozens of manufacturers to enter the market.[52][60] Its creator Nishikado not only designed and programmed the game, but also did the artwork, engineered the arcade hardware, and put together a microcomputer from scratch.[61] It was soon ported to the Atari 2600, becoming the first "killer app" and quadrupling the console's sales.[62] At the same time, home computers appeared on the market, allowing individual programmers and hobbyists to develop games. This allowed hardware manufacturer and software manufacturers to act separately. A very large number of games could be produced by an individual, as games were easy to make because graphical and memory limitation did not allow for much content. Larger companies developed, who focused selected teams to work on a title.[63] The developers of many early home video games, such as Zork, Baseball, Air Warrior, and Adventure, later transitioned their work as products of the early video game industry.[citation needed]

The industry expanded significantly at the time, with the arcade video game sector alone (representing the largest share of the gaming industry) generating higher revenues than both pop music and Hollywood films combined.[64] The home video game industry, however, suffered major losses following the video game crash of 1983.[65] In 1984 Jon Freeman warned in Computer Gaming World:

Q: Are computer games the way to fame and fortune?

A: No. Not unless your idea of fame is having your name recognized by one or two astute individuals at Origins ... I've been making a living (after a fashion) designing games for most of the last six years. I wouldn't recommend it for someone with a weak heart or a large appetite, though.[66]

Chris Crawford and Don Daglow in 1987 similarly advised prospective designers to write games as a hobby first, and to not quit their existing jobs early.[67][68] The home video game industry was revitalized soon after by the widespread success of the Nintendo Entertainment System.[69]

Compute!'s Gazette in 1986 stated that although individuals developed most early video games, "It's impossible for one person to have the multiple talents necessary to create a good game".[70] By 1987 a video game required 12 months to develop and another six to plan marketing. Projects remained usually solo efforts, with single developers delivering finished games to their publishers.[68] With the ever-increasing processing and graphical capabilities of arcade, console, and computer products, along with an increase in user expectations, game design moved beyond the scope of a single developer to produce a marketable game.[71] The Gazette stated, "The process of writing a game involves coming up with an original, entertaining concept, having the skill to bring it to fruition through good, efficient programming, and also being a fairly respectable artist".[70] This sparked the beginning of team-based development.[citation needed] In broad terms, during the 1980s, pre-production involved sketches and test routines of the only developer. In the 1990s, pre-production consisted mostly of game art previews. In the early 2000s, pre-production usually produced a playable demo.[72]

In 2000 a 12 to 36 month development project was funded by a publisher for US$1M–3M.[73] Additionally, $250k–1.5M were spent on marketing and sales development.[74] In 2001, over 3000 games were released for PC; and from about 100 games turning profit only about 50 made significant profit.[73] In the early 2000s it became increasingly common to use middleware game engines, such as Quake engine or Unreal Engine.[75]

In the early 2000s, also mobile games started to gain popularity. However, mobile games distributed by mobile operators remained a marginal form of gaming until the Apple App Store was launched in 2008.[40]

In 2005, a mainstream console video game cost from US$3M to $6M to develop. Some games cost as much as $20M to develop.[76] In 2006 the profit from a console game sold at retail was divided among parties of distribution chain as follows: developer (13%), publisher (32%), retail (32%), manufacturer (5%), console royalty (18%).[38] In 2008 a developer would retain around 17% of retail price and around 85% if sold online.[12]

Since the third generation of consoles, the home video game industry has constantly increased and expanded. The industry revenue has increased at least five-fold since the 1990s. In 2007, the software portion of video game revenue was $9.5 billion, exceeding that of the movie industry.[77]

The Apple App Store, introduced in 2008, was the first mobile application store operated directly by the mobile-platform holder. It significantly changed the consumer behaviour more favourable for downloading mobile content and quickly broadened the markets of mobile games.[40]

In 2009 games' market annual value was estimated between $7–30 billion, depending on which sales figures are included. This is on par with films' box office market.[78] A publisher would typically fund an independent developer for $500k–$5M for a development of a title.[35] In 2012, the total value had already reached $66.3 billion and by then the video game markets were no longer dominated by console games. According to Newzoo, the share of MMO's was 19.8%, PC/MAC's 9.8%, tablets' 3.2%, smartphones 10.6%, handhelds' 9.8%, consoles' only 36.7% and online casual games 10.2%. The fastest growing market segments being mobile games with an average annual rate of 19% for smartphones and 48% for tablets.[79]

In the past several years, many developers opened and many closed down. Each year a number of developers are acquired by larger companies or merge with existing companies. For example, in 2007 Blizzard Entertainment's parent company, Vivendi Games merged with Activision. In 2008 Electronic Arts nearly acquired Take-Two Interactive. In 2009 Midway Games was acquired by Time-Warner and Eidos Interactive merged with Square Enix.[80]

Roles

[edit]Producer

[edit]Development is overseen by internal and external producers.[81][82] The producer working for the developer is known as the internal producer and manages the development team, schedules, reports progress, hires and assigns staff, and so on.[82][83] The producer working for the publisher is known as the external producer and oversees developer progress and budget.[84] Producer's responsibilities include PR, contract negotiation, liaising between the staff and stakeholders, schedule and budget maintenance, quality assurance, beta test management, and localization.[82][85] This role may also be referred to as project manager, project lead, or director.[82][85]

Publisher

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2010) |

A video game publisher is a company that publishes video games that they have either developed internally or have had developed by an external video game developer. As with book publishers or publishers of DVD movies, video game publishers are responsible for their product's manufacturing and marketing, including market research and all aspects of advertising.

They usually finance the development, sometimes by paying a video game developer (the publisher calls this external development) and sometimes by paying an internal staff of developers called a studio. Consequently, they also typically own the IP of the game.[40] Large video game publishers also distribute the games they publish, while some smaller publishers instead hire distribution companies (or larger video game publishers) to distribute the games they publish.

Other functions usually performed by the publisher include deciding on and paying for any license that the game may utilize; paying for localization; layout, printing, and possibly the writing of the user manual; and the creation of graphic design elements such as the box design.

Large publishers may also attempt to boost efficiency across all internal and external development teams by providing services such as sound design and code packages for commonly needed functionality.[86]

Because the publisher usually finances development, it usually tries to manage development risk with a staff of producers or project managers to monitor the progress of the developer, critique ongoing development, and assist as necessary. Most video games created by an external video game developer are paid for with periodic advances on royalties. These advances are paid when the developer reaches certain stages of development, called milestones.

Independent video game developers create games without a publisher and may choose to digitally distribute their games.[citation needed]

Development team

[edit]Developers can range in size from small groups making casual games to housing hundreds of employees and producing several large titles.[17] Companies divide their subtasks of game development. Individual job titles may vary; however, roles are the same within the industry.[32] The development team consists of several members.[23] Some members of the team may handle more than one role; similarly, more than one task may be handled by the same member.[32] Team size can vary from 3 to 100 or more members, depending on the game's scope. The most represented are artists, followed by programmers, then designers, and finally, audio specialists, with one to three producers in management.[87] Many teams also include a dedicated writer with expertise in video game writing.[citation needed] These positions are employed full-time. Other positions, such as testers, may be employed only part-time.[87] Use of contractors for art, programming, and writing is standard within the industry.[citation needed] Salaries for these positions vary depending on both the experience and the location of the employee.[88]

A development team includes these roles or disciplines:[32]

Designer

[edit]A game designer is a person who designs gameplay, conceiving and designing the rules and structure of a game.[89][90][91] Development teams usually have a lead designer who coordinates the work of other designers. They are the main visionaries of the game.[92] One of the roles of a designer is being a writer, often employed part-time to conceive the game's narrative, dialogue, commentary, cutscene narrative, journals, video game packaging content, hint system, etc.[93][94][95] In larger projects, there are often separate designers for various parts of the game, such as, game mechanics, user interface, characters, dialogue, graphics, etc.[citation needed]

Artist

[edit]A game artist is a visual artist who creates video game art.[96][97] The art production is usually overseen by an art director or art lead, making sure their vision is followed. The art director manages the art team, scheduling and coordinating within the development team.[96]

The artist's job may be 2D oriented or 3D oriented. 2D artists may produce concept art,[98][99] sprites,[100] textures,[101][102] environmental backdrops or terrain images,[98][102] and user interface.[100] 3D artists may produce models or meshes,[103][104] animation,[103] 3D environment,[105] and cinematics.[105] Artists sometimes occupy both roles.[citation needed]

Programmer

[edit]A game programmer is a software engineer who primarily develops video games or related software (such as game development tools). The game's codebase development is handled by programmers.[106][107] There are usually one to several lead programmers,[108] who implement the game's starting codebase and overview future development and programmer allocation on individual modules. An entry-level programmer can make, on average, around $70,000 annually and an experienced programmer can make, on average, around $125,000 annually.[88]

Individual programming disciplines roles include:[106]

- Physics – the programming of the game engine, including simulating physics, collision, object movement, etc.;

- AI – producing computer agents using game AI techniques, such as scripting, planning, rule-based decisions, etc.

- Graphics – the managing of graphical content utilization and memory considerations; the production of the graphics engine, integration of models, textures to work along the physics engine.

- Sound – integration of music, speech, and effect sounds into the proper locations and times.

- Gameplay – implementation of various game rules and features (sometimes called a generalist);

- Scripting – development and maintenance of a high-level command system for various in-game tasks, such as AI, level editor triggers, etc.

- UI – production of user interface elements, like option menus, HUDs, help and feedback systems, etc.

- Input processing – processing and compatibility correlation of various input devices, such as keyboard, mouse, gamepad, etc.

- Network communications – the managing of data inputs and outputs for local and internet gameplay.

- Game tools – the production of tools to accompany the development of the game, especially for designers and scripters.

Level designer

[edit]A level designer is a person who creates levels, challenges or missions for video games using a specific set of programs.[109][110] These programs may be commonly available commercial 3D or 2D design programs, or specially designed and tailored level editors made for a specific game.

Level designers work with both incomplete and complete versions of the game. Game programmers usually produce level editors and design tools for the designers to use. This eliminates the need for designers to access or modify game code.[111] Level editors may involve custom high-level scripting languages for interactive environments or AIs. As opposed to the level editing tools sometimes available to the community, level designers often work with placeholders and prototypes aiming for consistency and clear layout before the required artwork is completed.

Sound engineer

[edit]Sound engineers are technical professionals responsible for sound effects and sound positioning. They are sometimes involved in creating haptic feedback, as was the case with the Returnal game sound team at PlayStation Studios Creative Arts in London.[112] They sometimes oversee voice acting and other sound asset creation.[113][114] Composers who create a game's musical score also comprise a game's sound team, though often this work is outsourced.

Tester

[edit]The quality assurance is carried out by game testers. A game tester analyzes video games to document software defects as part of a quality control. Testing is a highly technical field requiring computing expertise and analytic competence.[102][115]

The testers ensure that the game falls within the proposed design: it both works and is entertaining.[116] This involves testing of all features, compatibility, localization, etc. Although necessary throughout the whole development process, testing is expensive and is often actively utilized only towards the completion of the project.

Development process

[edit]Game development is a software development process, as a video game is software with art, audio, and gameplay. Formal software development methods are often overlooked.[3] Games with poor development methodology are likely to run over budget and time estimates, as well as contain a large number of bugs. Planning is important for individual[11] and group projects alike.[73]

Overall game development is not suited for typical software life cycle methods, such as the waterfall model.[117]

One method employed for game development is agile development.[118] It is based on iterative prototyping, a subset of software prototyping.[119] Agile development depends on feedback and refinement of the game's iterations with a gradually increasing feature set.[120] This method is effective because most projects do not start with a clear requirement outline.[118] A popular method of agile software development is Scrum.[121]

Another successful method is Personal Software Process (PSP) requiring additional staff training to increase awareness of project planning.[122] This method is more expensive and requires commitment of team members. PSP can be extended to Team Software Process, where the whole team is self-directing.[123]

Game development usually involves an overlap of these methods.[117] For example, asset creation may be done via waterfall model, because requirements and specification are clear,[124] but gameplay design might be done using iterative prototyping.[124]

There are many types of commonly used programming languages for game development as more suitable. Java and Javascript are top choices due to animation capability. Many 3D games also use C++ or C#. Python also has many libraries that can produce suitable game development. Minecraft for example is built entirely through java. When programming the game the developers can either program the game animation using many graphical design libraries within the programming language. Or if not they can load images direct into memory using the code to be the game animation. Java has a high functionality for loading images into memory. <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Programming_game> Development of a commercial game usually includes the following stages:[125][126]

Pre-production

[edit]Pre-production[127] or design phase[72] is a planning phase of the project focused on idea and concept development and production of initial design documents.[126][128][129][130] The goal of concept development is to produce clear and easy to understand documentation,[126][131] which describes all the tasks, schedules and estimates for the development team.[132] The suite of documents produced in this phase is called production plan.[133] This phase is usually not funded by a publisher,[126] however good publishers may require developers to produce plans during pre-production.[132]

The concept documentation can be separated into three stages or documents—high concept, pitch and concept;[125][134] however, there is no industry standard naming convention, for example, both Bethke (2003) and Bates (2004) refer to pitch document as "game proposal",[127][132] yet Moore, Novak (2010) refers to concept document as "game proposal".[125]

The late stage of pre-production may also be referred to as proof of concept,[127] or technical review[125] when more detailed game documents are produced.

Publishers have started to expect broader game proposals even featuring playable prototypes.[135]

High concept

[edit]High concept is a brief description of a game.[125][127] The high concept is the one-or two-sentence response to the question, "What is your game about?".

Pitch

[edit]A pitch,[125][127] concept document,[125] proposal document,[132] or game proposal[127] is a short summary document intended to present the game's selling points and detail why the game would be profitable to develop.[125][127]

Verbal pitches may be made to management within the developer company, and then presented to publishers.[136] A written document may need to be shown to publishers before funding is approved.[132] A game proposal may undergo one to several green-light meetings with publisher executives who determine if the game is to be developed.[137] The presentation of the project is often given by the game designers.[138] Demos may be created for the pitch; however may be unnecessary for established developers with good track records.[138]

If the developer acts as its own publisher, or both companies are subsidiaries of a single company, then only the upper management needs to give approval.[138]

Concept

[edit]Concept document,[127] game proposal,[125] or game plan[139] is a more detailed document than the pitch document.[125][127][131] This includes all the information produced about the game.[139] This includes the high concept, game's genre, gameplay description, features, setting, story, target audience, hardware platforms, estimated schedule, marketing analysis, team requirements, and risk analysis.[140]

Before an approved design is completed, a skeleton crew of programmers and artists usually begins work.[138] Programmers may develop quick-and-dirty prototypes showcasing one or more features that stakeholders would like to see incorporated in the final product.[138] Artists may develop concept art and asset sketches as a springboard for developing real game assets.[138] Producers may work part-time on the game at this point, scaling up for full-time commitment as development progresses.[138] Game producer's work during pre-production is related to planning the schedule, budget and estimating tasks with the team.[138] The producer aims to create a solid production plan so that no delays are experienced at the start of the production.[138]

Game design document

[edit]Before a full-scale production can begin, the development team produces the first version of a game design document incorporating all or most of the material from the initial pitch.[141][142] The design document describes the game's concept and major gameplay elements in detail. It may also include preliminary sketches of various aspects of the game. The design document is sometimes accompanied by functional prototypes of some sections of the game.[citation needed] The design document remains a living document throughout the development—often changed weekly or even daily.[143]

Compiling a list of game's needs is called "requirement capture".[11]

Prototype

[edit]

Writing prototypes of gameplay ideas and features is an important activity that allows programmers and game designers to experiment with different algorithms and usability scenarios for a game. A great deal of prototyping may take place during pre-production before the design document is complete and may, in fact, help determine what features the design specifies. Prototyping at this stage is often done manually, (paper prototyping), not digitally,[citation needed] as this is often easier and faster to test and make changes before wasting time and resources on what could be a canceled idea or project. Prototyping may also take place during active development to test new ideas as the game emerges.

Prototypes are often meant only to act as a proof of concept or to test ideas, by adding, modifying or removing some of the features.[144] Most algorithms and features debuted in a prototype may be ported to the game once they have been completed.

Often prototypes need to be developed quickly with very little time for up-front design (around 20 to 25§ minutes of testing).[citation needed] Therefore, usually very prolific programmers are called upon to quickly code these testbed tools. RAD tools may be used to aid in the quick development of these programs. In case the prototype is in a physical form, programmers and designers alike will make the game with paper, dice, and other easy-to-access tools in order to make the prototype faster.

A successful development model is iterative prototyping, where design is refined based on current progress. There are various technology available for video game development[145]

Production

[edit]Production is the main stage of development when assets and source code for the game are produced.[146]

Mainstream production is usually defined as the period of time when the project is fully staffed.[citation needed] Programmers write new source code, artists develop game assets, such as, sprites or 3D models. Sound engineers develop sound effects and composers develop music for the game. Level designers create levels, and writers write dialogue for cutscenes and NPCs.[original research?] Game designers continue to develop the game's design throughout production.

Design

[edit]Game design is an essential and collaborative[147] process of designing the content and rules of a game,[148] requiring artistic and technical competence as well as writing skills.[149] Creativity and an open mind are vital for the completion of a successful video game.

During development, the game designer implements and modifies the game design to reflect the current vision of the game. Features and levels are often removed or added. The art treatment may evolve and the backstory may change. A new platform may be targeted as well as a new demographic. All these changes need to be documented and disseminated to the rest of the team. Most changes occur as updates to the design document.

Programming

[edit]The programming of the game is handled by one or more game programmers. They develop prototypes to test ideas, many of which may never make it into the final game. The programmers incorporate new features demanded by the game design and fix any bugs introduced during the development process. Even if an off-the-shelf game engine is used, a great deal of programming is required to customize almost every game.

Level creation

[edit]From a time standpoint, the game's first level takes the longest to develop. As level designers and artists use the tools for level building, they request features and changes to the in-house tools that allow for quicker and higher-quality development. Newly introduced features may cause old levels to become obsolete, so the levels developed early on may be repeatedly developed and discarded. Because of the dynamic environment of game development, the design of early levels may also change over time. It is not uncommon to spend upwards of twelve months on one level of a game developed over the course of three years. Later levels can be developed much more quickly as the feature set is more complete and the game vision is clearer and more stable.

Art production

[edit]During development, artists make art assets according to specifications given by the designers. Early in production, concept artists make concept art to guide the artistic direction of the game, rough art is made for prototypes, and the designers work with artists to design the visual style and visual language of the game. As production goes on, more final art is made, and existing art is edited based on player feedback.

Audio production

[edit]Game audio may be separated into three categories—sound effects, music, and voice-over.[150]

Sound effect production is the production of sounds by either tweaking a sample to a desired effect or replicating it with real objects.[150] Sound effects include UI sound design, which effectively conveys information both for visible UI elements and as an auditory display. It provides sonic feedback for in-game interfaces, as well as contributing to the overall game aesthetic.[151] Sound effects are important and impact the game's delivery.[152]

Music may be synthesized or performed live.[153]

There are four main ways in which music is presented in a game.

- Music may be ambient, especially for slow periods of game, where the music aims to reinforce the aesthetic mood and game setting.[154]

- Music may be triggered by in-game events. For example, in such games as Pac-Man or Mario, player picking up power-ups triggered respective musical scores.[154]

- Action music, such as chase, battle or hunting sequences is fast-paced, hard-changing score.[155]

- Menu music, similar to credits music, creates aural impact while relatively little action is taking place.[155]

A game title with 20 hours of single-player gameplay may feature around 1 hour.[155]

Testing

[edit]Quality assurance of a video game product plays a significant role throughout the development cycle of a game, though comes more significantly into play as the game nears completion. Unlike other software products or productivity applications, video games are fundamentally meant to entertain, and thus the testing of video games is more focused on the end-user experience rather than the accuracy of the software code's performance, which leads to differences in how the game software is developed.[156]

Because game development is focused on the presentation and gameplay as seen by the player, there often is little rigor in maintaining and testing backend code in the early stages of development since such code may be readily disregarded if there are changes found in gameplay. Some automated testing may be used to ensure the core game engine operates as expected, but most game testing comes via game tester, who enter the testing process once a playable prototype is available. This may be one level or subset of the game software that can be used to any reasonable extent.[156] The use of testers may be lightweight at the early stages of development, but the testers' role becomes more predominant as the game nears completion, becoming a full-time role alongside development.[156] Early testing is considered a key part of game design; the most common issue raised in several published post-mortems on game development was the failure to start the testing process early.[156]

As code matures and the gameplay features solidify, then development typically includes more rigorous test controls such as regression testing to make sure new updates to the code base do not change working parts of the game. Games are complex software systems, and changes in one code area may unexpected cause a seemingly unrelated part of the game to fail. Testers are tasked to repeatedly play through updated versions of games in these later stages to look for any issues or bugs not otherwise found from automated testing. Because this can be a monotonous task of playing the same game over and over, this process can lead to games frequently being released with uncaught bugs or glitches.[156]

There are other factors simply inherent to video games that can make testing difficult. This includes the use of randomized gameplay systems, which require more testing for both game balance and bug tracking than more linearized games, the balance of cost and time to devote to testing as part of the development budget, and assuring that the game still remains fun and entertaining to play as changes are made to it.[156]

Despite the dangers of overlooking regression testing, some game developers and publishers fail to test the full feature suite of the game and ship a game with bugs. This can result in customer dissatisfaction and failure to meet sales goals. When this does happen, most developers and publishers quickly release patches that fix the bugs and make the game fully playable again.[156] Certain publishing models are designed specifically to accommodate the fact that first releases of games may be bug-ridden but will be fixed post-release. The early access model invites players to pay into a game before its planned release and helps to provide feedback and bug reports.[156] Mobile games and games with live services are also anticipated to be updated on a frequent basis, offset by pre-release testing with live feedback and bug reports.[156]

Milestones

[edit]

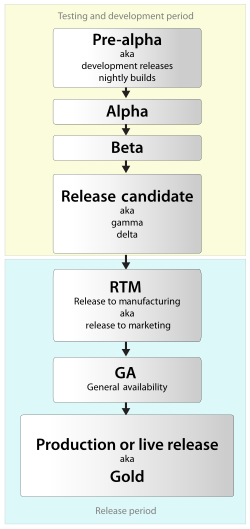

Commercial game development projects may be required to meet milestones set by the publisher. Milestones mark major events during game development and are used to track game's progress.[157] Such milestones may be, for example, first playable,[158][159] alpha,[160][161] or beta[161] game versions. Project milestones depend on the developer schedules.[157]

Milestones are usually based on multiple short descriptions for functionality; examples may be "Player roaming around in-game environment" or "Physics working, collisions, vehicle" etc. (numerous descriptions are possible). These milestones are usually how the developer gets paid; sometimes as "an advance against royalty". These milestones are listed, anywhere from three to twenty depending on the developer and publisher. The milestone list is usually a collaborative agreement between the publisher and developer. The developer usually advocates for making the milestone descriptions as simple as possible; depending on the specific publisher - the milestone agreements may get very detailed for a specific game. When working with a good publisher, the "spirit of the law" is usually adhered to regarding milestone completion... in other words, if the milestone is 90% complete the milestone is usually paid with the understanding that it will be 100% complete by the next due milestone. It is a collaborative agreement between publisher and developer, and usually (but not always) the developer is constrained by heavy monthly development expenses that need to be met. Also, sometimes milestones are "swapped", the developer or publisher may mutually agree to amend the agreement and rearrange milestone goals depending on changing requirements and development resources available. Milestone agreements are usually included as part of the legal development contracts. After each "milestone" there is usually a payment arrangement. Some very established developers may simply have a milestone agreement based on the amount of time the game is in development (monthly/quarterly) and not specific game functionality - this is not as common as detailed functionality "milestone lists".

There is no industry standard for defining milestones, and such varies depending on publisher, year, or project.[162] Some common milestones for a two-year development cycle are as follows:[157]

First playable

[edit]The first playable is the game version containing representative gameplay and assets,[157] this is the first version with functional major gameplay elements.[158] It is often based on the prototype created in pre-production.[159] Alpha and first playable are sometimes used to refer to a single milestone, however, large projects require first playable before feature complete alpha.[158] First playable occurs 12 to 18 months before code release. It is sometimes referred to as the "Pre-Alpha" stage.[161]

Alpha

[edit]Alpha is the stage when key gameplay functionality is implemented, and assets are partially finished.[161] A game in alpha is feature complete, that is, the game is playable and contains all the major features.[162] These features may be further revised based on testing and feedback.[161] Additional small, new features may be added, and similarly planned, but unimplemented features may be dropped.[162] Programmers focus mainly on finishing the codebase, rather than implementing additions.[160]

Code freeze

[edit]Code freeze is the stage when new code is no longer added to the game and only bugs are being corrected. Code freeze occurs three to four months before code release.[161]

Beta

[edit]Beta is a feature and asset complete version of the game, when only bugs are being fixed.[160][161] This version contains no bugs that prevent the game from being shippable.[160] No changes are made to the game features, assets, or code. Beta occurs two to three months before code release.[161]

Code release

[edit]Code release is the stage when many bugs are fixed and game is ready to be shipped or submitted for console manufacturer review. This version is tested against the QA test plan. First code release candidate is usually ready three to four weeks before code release.[161]

Gold master

[edit]Gold master is the final game's build that is used as a master for the production of the game.[163]

Release schedules and "crunch time"

[edit]In most AAA game development, games are announced a year or more in advance and given a planned release date or approximate window so that they can promote and market the game, establish orders with retailers, and entice consumers to pre-order the game. Delaying the release of a video game can have a negative financial impact on publishers and developers, and extensive delays may lead to project cancellation and employee layoffs.[164] To ensure a game makes a set release date, publishers and developers may require their employees to work overtime to complete the game, which is considered common in the industry.[165] This overtime is often referred to as "crunch time" or "crunch mode".[166] In 2004 and afterwards, the culture of crunch time in the industry came under scrutiny, leading many publishers and developers to reduce the expectation on developers for overtime work and better schedule management, though crunch time still can occur.[167]

Post-production

[edit]After the game goes gold and ships, some developers will give team members comp time (perhaps up to a week or two) to compensate for the overtime put in to complete the game, though this compensation is not standard.[citation needed]

Maintenance

[edit]Once a game ships, the maintenance phase for the video game begins.[168]

Games developed for video game consoles have had almost no maintenance period in the past. The shipped game would forever house as many bugs and features as when released. This was common for consoles since all consoles had identical or nearly identical hardware; making incompatibility, the cause of many bugs, a non-issue. In this case, maintenance would only occur in the case of a port, sequel, or enhanced remake that reuses a large portion of the engine and assets.[citation needed]

In recent times popularity of online console games has grown, and online capable video game consoles and online services such as Xbox Live for the Xbox have developed. Developers can maintain their software through downloadable patches. These changes would not have been possible in the past without the widespread availability of the Internet.[citation needed]

PC development is different. Game developers try to account for the majority of configurations and hardware. However, the number of possible configurations of hardware and software inevitably leads to the discovery of game-breaking circumstances that the programmers and testers did not account for.[citation needed]

Programmers wait for a period to get as many bug reports as possible. Once the developer thinks they've obtained enough feedback, the programmers start working on a patch. The patch may take weeks or months to develop, but it is intended to fix most accounted bugs and problems with the game that were overlooked in past code releases, or in rare cases, fix unintended problems caused by previous patches. Occasionally a patch may include extra features or content or may even alter gameplay.[citation needed]

In the case of a massively multiplayer online game (MMOG), such as a MMORPG or MMORTS, the shipment of the game is the starting phase of maintenance.[168] The maintenance staff for such an online game can number in the dozens, sometimes including members of the original programming team,[citation needed] as the game world is continuously changed and iterated and new features are added. Some developers implement a public test realm or player test realm (PTR) in order to test out significant upcoming changes prior to release. These specialized servers offer similar benefits as beta testing, where players get to preview new features while the developer gathers data about bugs and game balance.[169][170]

Outsourcing

[edit]Several development disciplines, such as audio, dialogue, or motion capture, occur for relatively short periods of time. Efficient employment of these roles requires either a large development house with multiple simultaneous title productions or outsourcing from third-party vendors.[171] Employing personnel for these tasks full-time is expensive,[172] so a majority of developers outsource a portion of the work. Outsourcing plans are conceived during the pre-production stage; where the time and finances required for outsourced work are estimated.[173]

- The music cost ranges based on the length of composition, method of performance (live or synthesized), and composer experience.[174] In 2003 a minute of high-quality synthesized music cost between US$600-1.5k.[154] A title with 20 hours of gameplay and 60 minutes of music may have cost $50k-60k for its musical score.[155]

- Voice acting is well-suited for outsourcing as it requires a set of specialized skills. Only large publishers employ in-house voice actors.[175]

- Sound effects can also be outsourced.[152]

- Programming is generally outsourced less than other disciplines, such as art or music. However, outsourcing for extra programming work or savings in salaries has become more common in recent years.[176][177][178][179][180][181]

Ghost development

[edit]Outsourced work is sometimes anonymous, i.e. not credited on the final product. This might go against the wishes of the developer, or it is something they reluctantly consent to because it is the only work they can get.[182] See Video game controversies § Lack of crediting for more information on this.

However, anonymity can also be agreed upon, or even desired by the outsourced party. A 2015 Polygon article stated that this practice is known as ghost development.[183] Ghost developers are hired by other developers to provide assistance, by publishers to develop a title they designed, or by companies outside the gaming industry. These businesses prefer to keep this hidden from the public to protect their brand equity, not wanting consumers or investors to know that they rely on external help. Ghost development can involve (small) portions of a project, but there have been instances of entire games being outsourced without the studio being credited.[183]

Ghost development has a particularly long history in the Japanese video game industry.[184] Probably the best-known example is Tose. Founded in 1979, this 'behind-the-scenes' agent has either developed or helped develop over 2,000 games as of 2017, most of them anonymously. This includes uncredited contributions to multiple Resident Evil, Metal Gear, and Dragon Quest titles.[185][186] Another example is Tokyo-based Hyde, which worked on Final Fantasy, Persona, and Yakuza games.[187] Its president, Kenichi Yanagihara, stated that the approach stems from Japanese culture, in which many people prefer not to seek the limelight.[188]

Marketing

[edit]The game production has similar distribution methods to those of music and film industries.[35]

The publisher's marketing team targets the game for a specific market and then advertises it.[189] The team advises the developer on target demographics and market trends,[189] as well as suggests specific features.[190] The game is then advertised and the game's high concept is incorporated into the promotional material, ranging from magazine ads to TV spots.[189] Communication between developer and marketing is important.[190]

The length and purpose of a game demo depends on the purpose of the demo and target audience. A game's demo may range between a few seconds (such as clips or screenshots) to hours of gameplay. The demo is usually intended for journalists, buyers, trade shows, general public, or internal employees (who, for example, may need to familiarize with the game to promote it). Demos are produced with public relations, marketing and sales in mind, maximizing the presentation effectiveness.[191]

Trade show demo

[edit]As a game nears completion, the publisher will want to showcase a demo of the title at trade shows. Many games have a "Trade Show demo" scheduled.[citation needed]

The major annual trade shows are, for example, Electronic Entertainment Expo (E3) or Penny Arcade Expo (PAX).[192] E3 is the largest show in North America.[193] E3 is hosted primarily for marketing and business deals. New games and platforms are announced at E3 and it received broad press coverage.[78][194] Thousands of products are on display and press demonstration schedules are kept.[194] In the 2000s E3 became a more closed-door event and many advertisers have withdrawn, reducing E3's budget.[78] PAX, created by authors of Penny Arcade blog and web-comic, is a mature and playful event with a player-centred philosophy.[35]

Localization

[edit]A game created in one language may also be published in other countries which speak a different language. For that region, the developers may want to translate the game to make it more accessible. For example, some games created for PlayStation Vita were initially published in Japanese language, like Soul Sacrifice. Non-native speakers of the game's original language may have to wait for the translation of the game to their language. But most modern big-budget games take localization into account during the development process and the games are released in several different languages simultaneously.[195]

Localization is the process of translating the language assets in a game into other languages.[196] By localizing games, they increase their level of accessibility where games could help to expend the international markets effectively. Game localization is generally known as language translations yet a "full localization" of a game is a complex project. Different levels of translation range from: zero translation being that there is no translation to the product and all things are sent raw, to basic translation where only a few text and subtitles are translated or even added, and full translation where new voiceovers and game material changes are added.[citation needed]

There are various essential elements in localizing a game including translating the language of the game to adjusting in-game assets for different cultures to reach more potential consumers in other geographies (or globalization for short). The translation seems to fall into the scope of localization, which itself constitutes a substantially broader endeavour.[197] These include the different levels of translation to the globalization of the game itself. However, certain developers seem to be divided on whether globalization falls under localization or not.[citation needed]

Moreover, to fit into the local markets, game production companies often change or redesign the graphic designs or the packaging of the game for marketing purposes. For example, the popular game Assassin's Creed has two different packaging designs for the European and US markets.[198] By localizing the graphics and packaging designs, companies might arouse better connections and attention from the consumers from various regions.[citation needed]

Development costs

[edit]The costs of developing a video game varies widely depending on several factors including team size, game genre and scope, and other factors such as intellectual property licensing costs. Most video game consoles also require development licensing costs which include game development kits for building and testing software. Game budgets also typically include costs for marketing and promotion, which can be on the same order in cost as the development budget.[199]

Prior to the 1990s, game development budgets, when reported, typically were on the average of US$1–5 million, with known outliers, such as the $20–25 million that Atari had paid to license the rights for E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial in addition to development costs.[200][201] The adoption of technologies such as 3D hardware rendering and CD-ROM integration by the mid-1990s, enabling games with more visual fidelity compared to prior titles, caused developers and publishers to put more money into game budgets as to flesh out narratives through cutscenes and full-motion video, and creating the start of the AAA video game industry. Some of the most expensive titles to develop around this time, approaching costs typical of major motion picture production budgets, included Final Fantasy VII in 1997 with an estimated budget of $40–45 million,[202] and Shenmue in 1999 with an estimated budget of $47–70 million.[203]Final Fantasy VII, with its marketing budget, had a total estimated cost of $80–145 million.[204]

Raph Koster, a video game designer and economist, evaluated published development budgets (less any marketing) for over 250 games in 2017 and reported that since the mid-1990s, there has been a type of Moore's Law in game budgets, with the average budget doubling about every five years after accounting for inflation. Koster reported average budgets were around $100 million by 2017, and could reach over $200 million by the early 2020s. Koster asserts these trends are partially tied to the technological Moore's law that gave more computational power for developers to work into their games, but also related to expectations for content from players in newer games and the number of players games are expected to draw.[205] Shawn Layden, former CEO of Sony Interactive Entertainment, affirmed that the costs for each generation of PlayStation consoles nearly doubled, with PlayStation 4 games have average budgets of $100 million and anticipating that PlayStation 5 games could reach $200 million.[206]

The rising costs of budgets of AAA games in the early 2000s led publishers to become risk-averse, staying to titles that were most likely to be high-selling games to recoup their costs. As a result of this risk aversion, the selection of AAA games in the mid-2000s became rather similar, and gave the opportunity for indie games that provided more experimental and unique gameplay concepts to expand around that time.[207]

Costs of development for AAA games continued to rise over the next two decades; a report by the United Kingdom's Competition and Markets Authority regarding the proposed acquisition of Activision Blizzard by Microsoft in 2023. Costs slowing increased from 1–4 million in 2000, to over $5 million in 2006, then to over $20 million by 2010, followed by $50 million to $150 million by 2018, and $200 million and up by 2023. In some cases, several AAA games exceeded $1 billion to make, split between $500-$600M to develop and a similar amount for marketing.[208] In court documents from regulatory review of the Activision Blizzard merger, reviewed by The Verge, the costs of Sony's first party games like Horizon Forbidden West and The Last of Us Part II had exceeded $200 million.[209]

Indie development

[edit]Independent games or indie games[210] are produced by individuals and small teams with no large-scale developer or publisher affiliations.[210][211][212] Indie developers generally rely on Internet distribution schemes. Many hobbyist indie developers create mods of existing games. Indie developers are credited for creative game ideas (for example, Darwinia, Weird Worlds, World of Goo). Current economic viability of indie development is questionable, however in recent years internet delivery platforms, such as, Xbox Live Arcade and Steam have improved indie game success.[210] In fact, some indie games have become very successful, such as Braid,[213] World of Goo,[214] and Minecraft.[215] In recent years many communities have emerged in support of indie games such as the popular indie game marketplace Itch.io, indie game YouTube channels and a large indie community on Steam. It is common for indie game developers to release games for free and generate revenue through other means such as microtransactions (in-game transactions), in-game advertisements and crowd-funding services like Patreon and Kickstarter.[citation needed]

Game industry

[edit]The video game industry (formally referred to as interactive entertainment) is the economic sector involved with the development, marketing and sale of video games. The industry sports several unique approaches.[citation needed]

The examples and perspective in this section may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (September 2008) |

Locales

[edit]United States

[edit]In the United States, in the early history of video game development, the prominent locale for game development was the corridor from San Francisco to Silicon Valley in California.[216] Most new developers in the US open near such "hot beds".[16]

At present, many large publishers still operate there, such as: Activision Blizzard, Capcom Entertainment, Crystal Dynamics, Electronic Arts, Namco Bandai Games, Sega of America, and Sony Computer Entertainment America. However, due to the nature of game development, many publishers are present in other regions, such as Big Fish Games (Washington), Majesco Entertainment (New Jersey), Microsoft Corporation (Washington), Nintendo of America (Washington), and Take-Two Interactive (New York),[217]

Education

[edit]Many universities and design schools are offering classes specifically focused on game development.[15] Some have built strategic alliances with major game development companies.[218][219] These alliances ensure that students have access to the latest technologies and are provided the opportunity to find jobs within the gaming industry once qualified.[citation needed] Many innovative ideas are presented at conferences, such as Independent Games Festival (IGF) or Game Developers Conference (GDC).

Indie game development may motivate students who produce a game for their final projects or thesis and may open their own game company.[210]

Stability

[edit]Video game industry employment is fairly volatile, similar to other artistic industries including television, music, etc. Scores of game development studios crop up, work on one game, and then quickly go under.[220] This may be one reason why game developers tend to congregate geographically; if their current studio goes under, developers can flock to an adjacent one or start another from the ground up.[citation needed]

In an industry where only the top 20% of products make a profit,[221] it is easy to understand this fluctuation. Numerous games may start development and are cancelled, or perhaps even completed but never published. Experienced game developers may work for years and yet never ship a title: such is the nature of the business.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Comparing Popular Game Engines". PubNub. Retrieved 2025-01-19.

- ^ "The Two Engines Driving the $120B Gaming Industry Forward". CB Insights Research. 2018-09-20. Retrieved 2020-06-03.

- ^ a b Bethke 2003, p. 4.

- ^ Bethke 2003, p. 7.

- ^ Bethke 2003, p. 14.

- ^ Bethke 2003, p. 12.

- ^ Melissinos, Chris (22 September 2015). "Video Games Are the Most Important Art Form in History". TIME. Retrieved 2020-06-09.

- ^ Bates 2004, p. 239.

- ^ "How Video Games Are Made". Britannica. Retrieved 12 November 2025.

- ^ Bethke 2003, p. 17.

- ^ a b c Bethke 2003, p. 3.

- ^ a b c Irwin, Mary Jane (November 20, 2008). "Indie Game Developers Rise Up". Forbes. Retrieved January 10, 2011.

- ^ Bethke 2003, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Bethke 2003, p. 18.

- ^ a b Moore & Novak 2010, p. 19.

- ^ a b c Moore & Novak 2010, p. 17.

- ^ a b c Moore & Novak 2010, p. 37.

- ^ Moore & Novak 2010, p. 18.

- ^ Crossley, Rob (January 11, 2010). "Study: Average dev costs as high as $28m". Archived from the original on January 13, 2010. Retrieved October 17, 2010.

- ^ Adams & Rollings 2006, p. 13.

- ^ a b c Chandler 2009, p. xxi.

- ^ a b Reimer, Jeremy (November 7, 2005). "Cross-platform game development and the next generation of consoles — Introduction". Retrieved October 17, 2010.

- ^ a b c Moore & Novak 2010, p. 5.

- ^ a b Bates 2004, p. 3.

- ^ Adams & Rollings 2006, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Bethke 2003, p. 75.

- ^ Chandler 2009, p. 3.

- ^ Adams & Rollings 2006, pp. 31–33.

- ^ a b Bates 2004, p. 6.

- ^ Oxland 2004, p. 25.

- ^ Bates 2004, pp. 14–16.

- ^ a b c d e Bates 2004, p. 151.

- ^ a b McGuire & Jenkins 2009, p. 23.

- ^ Chandler 2009, p. xxi-xxii.

- ^ a b c d e f McGuire & Jenkins 2009, p. 25.

- ^ Chandler 2009, p. 82.

- ^ Chandler 2009, p. 87.

- ^ a b c McGuire & Jenkins 2009, p. 26.

- ^ Chandler 2009, p. 90.

- ^ a b c d e Behrmann M, Noyons M, Johnstone B, MacQueen D, Robertson E, Palm T, Point J (2012). "State of the Art of the European Mobile Games Industry" (PDF). Mobile GameArch Project. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-02. Retrieved 2013-08-12.

- ^ "Duke Nukem Forever release date disparity demystified". PC Gamer. 2011-03-24. Retrieved 2012-01-03.

- ^ Berghammer, Billy (2007-03-26). "The History Of Team Fortress 2". Game Informer. Archived from the original on 2007-04-03. Retrieved February 27, 2012.

- ^ McGuire & Jenkins 2009, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Moore & Novak 2010, p. 7.

- ^ a b Moore & Novak 2010, p. 6.

- ^ John Anderson. "Who Really Invented The Video Game?". Atari Magazines. Retrieved November 27, 2006.

- ^ Marvin Yagoda (2008). "1972 Nutting Associates Computer Space". Archived from the original on 2008-12-28.

- ^ Wolverton, Mark. "The Father of Video Games". American Heritage. Archived from the original on February 16, 2010. Retrieved March 31, 2010.

- ^ "History of Gaming - Interactive Timeline of Game History". PBS. Retrieved 2007-10-25.

- ^ Miller, Michael (2005-04-01). "A History of Home Video Game Consoles". InformIT. Archived from the original on 2007-10-12. Retrieved 2007-10-25.

- ^ Moore & Novak 2010, p. 9.

- ^ a b c Jason Whittaker (2004), The cyberspace handbook, Routledge, p. 122, ISBN 0-415-16835-X

- ^ "Gun Fight". AllGame. Archived from the original on 2014-01-01.

- ^ Stephen Totilo (August 31, 2010). "In Search Of The First Video Game Gun". Kotaku. Retrieved 2011-03-27.

- ^ Chris Kohler (2005), Power-Up: How Japanese Video Games Gave the World an Extra Life, BradyGames, p. 19, ISBN 0-7440-0424-1, retrieved 2011-03-27

- ^ Shirley R. Steinberg (2010), Shirley R. Steinberg; Michael Kehler; Lindsay Cornish (eds.), Boy Culture: An Encyclopedia, vol. 1, ABC-CLIO, p. 451, ISBN 978-0-313-35080-1, retrieved 2011-04-02

- ^ Chris Kohler (2005), Power-Up: How Japanese Video Games Gave the World an Extra Life, BradyGames, p. 18, ISBN 0-7440-0424-1, retrieved 2011-03-27

- ^ Steve L. Kent (2001), The ultimate history of video games: from Pong to Pokémon and beyond : the story behind the craze that touched our lives and changed the world, p. 64, Prima, ISBN 0-7615-3643-4

- ^ Moore & Novak 2010, p. 13.

- ^ Kent, Steven L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games: From Pong to Pokémon. Three Rivers Press. p. 500. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- ^ Edwards, Benj. "Ten Things Everyone Should Know About Space Invaders". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on 2009-02-26. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

- ^ "The Definitive Space Invaders". Retro Gamer (41). Imagine Publishing: 24–33. September 2007. Retrieved 2011-04-20.

- ^ Moore & Novak 2010, p. 12.

- ^ Everett M. Rogers & Judith K. Larsen (1984), Silicon Valley fever: growth of high-technology culture, Basic Books, p. 263, ISBN 0-465-07821-4, retrieved 2011-04-23,

Video game machines have an average weekly take of $109 per machine. The video arcade industry took in $8 billion in quarters in 1982, surpassing pop music (at $4 billion in sales per year) and Hollywood films ($3 billion). Those 32 billion arcade games played translate to 143 games for every man, woman, and child in America. A recent Atari survey showed that 86 percent of the US population from 13 to 20 has played some kind of video game and an estimated 8 million US homes have video games hooked up to the television set. Sales of home video games were $3.8 billion in 1982, approximately half that of video game arcades.

- ^ Jason Whittaker (2004), The cyberspace handbook, Routledge, pp. 122–3, ISBN 0-415-16835-X

- ^ Freeman, Jon (December 1984). "Should You Turn Pro?". Computer Gaming World. p. 16. Retrieved 2023-01-06.

- ^ "Designer Profile: Chris Crawford (Part 2)". Computer Gaming World. Jan–Feb 1987. pp. 56–59. Retrieved 2023-01-06.

- ^ a b Daglow, Don L. (Aug–Sep 1987). ""I Think We've Got a Hit..." / The Twisted Path to Success in Entertainment Software". Computer Gaming World. p. 8. Retrieved 2023-01-06.

- ^ Consalvo, Mia (2006). "Console video games and global corporations: Creating a hybrid culture". New Media & Society. 8 (1): 117–137. doi:10.1177/1461444806059921. S2CID 32331292.

- ^ a b Yakal, Kathy (June 1986). "The Evolution of Commodore Graphics". Compute!'s Gazette. pp. 34–42. Retrieved 2019-06-18.

- ^ "So What Do they Teach you at Videogame School?". Next Generation. No. 25. Imagine Media. January 1997. p. 10.

... the 1980s era when one person could make a hit game by himself is long gone. These days games cost in the millions of dollars to produce - and no investor is going to give this money to one guy working from his bedroom. In 1996, a game will probably employ 10 to 15 people, working for one or two years.

- ^ a b Bethke 2003, p. 26.

- ^ a b c Bethke 2003, p. 15.

- ^ Bethke 2003, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Bethke 2003, p. 30.

- ^ "Cost of making games set to soar". BBC News. November 17, 2005. Retrieved April 9, 2010.

- ^ Moore & Novak 2010, p. 15.

- ^ a b c McGuire & Jenkins 2009, p. 24.

- ^ "Global Games Market Grows to $86.1bn in 2016". Newzoo. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ^ Moore & Novak 2010, p. 16.

- ^ Bates 2004, p. 154.

- ^ a b c d Moore & Novak 2010, p. 71.

- ^ Bates 2004, pp. 156–158.

- ^ Bates 2004, pp. 154–156.

- ^ a b Bates 2004, p. 153.

- ^ "Understanding video game developers as an occupational community". Gamering. 2015-10-05.

- ^ a b Moore & Novak 2010, p. 25.

- ^ a b "Top Gaming Studios, Schools & Salaries". Big Fish Games. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012.

- ^ Salen & Zimmerman 2003.

- ^ Oxland 2004, p. 292.

- ^ Moore & Novak 2010, p. 74.

- ^ Oxland 2004, pp. 292–296.

- ^ Bates 2004, p. 163.

- ^ Brathwaite & Schreiber 2009, p. 171.

- ^ Moore & Novak 2010, p. 94.

- ^ a b Bates 2004, p. 171.

- ^ Moore & Novak 2010, p. 85.

- ^ a b Moore & Novak 2010, p. 86.

- ^ Bates 2004, p. 173.

- ^ a b Moore & Novak 2010, p. 87.

- ^ Moore & Novak 2010, p. 88.

- ^ a b c Bates 2004, p. 176.

- ^ a b Moore & Novak 2010, p. 89.

- ^ Bates 2004, p. 175.

- ^ a b Moore & Novak 2010, p. 90.

- ^ a b Bates 2004, p. 168.

- ^ Moore & Novak 2010, p. 78.

- ^ Bates 2004, p. 165.

- ^ Bates 2004, p. 162.

- ^ Moore & Novak 2010, p. 76.

- ^ Gómez-Maureira, Marcello A.; Westerlaken, Michelle; Janssen, Dirk P.; Gualeni, Stefano; Calvi, Licia (2014-12-01). "Improving level design through game user research: A comparison of methodologies". Entertainment Computing. 5 (4): 463–473. doi:10.1016/j.entcom.2014.08.008. ISSN 1875-9521.

- ^ "Creating Returnal's Glorious, Dark Electronic Sound (and making the most of PS5's new 3D audio engine)". 30 June 2021. Archived from the original on June 30, 2021. Retrieved January 6, 2022.

- ^ Bates 2004, pp. 185, 188, 191.

- ^ Moore & Novak 2010, p. 91.

- ^ Moore & Novak 2010, p. 95.

- ^ Bates 2004, p. 177.

- ^ a b Bates 2004, p. 225.

- ^ a b Bates 2004, pp. 218–219.

- ^ Bates 2004, pp. 226–227.

- ^ Chandler 2009, p. 47.

- ^ Chandler 2009, p. 41.

- ^ Chandler 2009, pp. 41, 43–44.

- ^ Chandler 2009, p. 44.

- ^ a b Bates 2004, p. 227.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Moore & Novak 2010, p. 70.

- ^ a b c d Bates 2004, p. 203.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Bates 2004, p. 204.

- ^ Adams & Rollings 2006, p. 29.

- ^ Oxland 2004, p. 251.

- ^ Chandler 2009, pp. 5–9.

- ^ a b Chandler 2009, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d e Bethke 2003, p. 102.

- ^ Bethke 2003, pp. 101–102.

- ^ Bates 2004, pp. 203–207.

- ^ Bethke 2003, p. 103.

- ^ Bates 2004, p. 274.

- ^ Bethke 2003, p. 27.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Zackariasson, Peter; Wilson, Timothy L. (2012). The Video Game Industry: Formation, Present State, and Future. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-89652-8.

- ^ a b Chandler 2009, p. 8.

- ^ Bates 2004, pp. 204–205.

- ^ Bates 2004, p. 276.

- ^ Oxland 2004, pp. 240, 274.

- ^ Oxland 2004, p. 241.

- ^ Brathwaite & Schreiber 2009, p. 189.

- ^ Bates 2004, p. 226.

- ^ Chandler 2009, p. 9.

- ^ Bates 2004, p. xxi.

- ^ Brathwaite & Schreiber 2009, p. 2.

- ^ Adams & Rollings 2006, pp. 20, 22–23, 24–25.

- ^ a b Bethke 2003, p. 49.

- ^ "How To Design Superb Sci-Fi UI Sound Effects". 22 March 2017. Archived from the original on March 15, 2021. Retrieved January 6, 2022.

- ^ a b Bethke 2003, p. 363.

- ^ Bethke 2003, p. 50.

- ^ a b c Bethke 2003, p. 344.

- ^ a b c d Bethke 2003, p. 345.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Politowski, Cristiano; Petrillo, Fabio; Guéhéneuc, Yann-Gäel (2021). "A Survey of Video Game Testing". arXiv:2103.06431 [cs.SE].

- ^ a b c d Chandler 2009, p. 244.

- ^ a b c Bethke 2003, p. 293.

- ^ a b Chandler 2009, p. 244–245.

- ^ a b c d Bethke 2003, p. 294.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Chandler 2009, p. 245.

- ^ a b c Bethke 2003, p. 192.

- ^ Bethke 2003, p. 295.

- ^ Moore & Novak 2010, p. 20,48.

- ^ Moore & Novak 2010, p. 241.

- ^ McShaffry 2009, p. 17.

- ^ Moore & Novak 2010, p. 48, 241.

- ^ a b Moore & Novak 2010, p. 97.

- ^ D'Onofrio, Matthew (9 May 2023). "New World Devs Discusses Their Development Process And How They Tackle Bugs". MMOBomb. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- ^ Tury, Jord (12 October 2022). "How To Access The PTR Server In World Of Warcraft". TheGamer. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- ^ Bethke 2003, p. 183.

- ^ Bethke 2003, pp. 183–184.

- ^ Bethke 2003, p. 184.

- ^ Bethke 2003, p. 343.

- ^ Bethke 2003, p. 353.

- ^ Bethke 2003, p. 185.

- ^ "Game Developer 2009 Outsourcing Report". Game Developer Research. Archived from the original on 2012-06-14. Retrieved 2013-08-15.

- ^ "An Examination of Outsourcing: The Developer Angle". Gamasutra. August 7, 2008.

- ^ "An Examination of Outsourcing Part 2: The Contractor Angle". Gamasutra. September 8, 2008.

- ^ Nutt, C. (April 4, 2011). "Virtuos: Setting The Record Straight On Outsourcing". Gamasutra.

- ^ "Devs: Ease Of Development Rules, Outsourcing On Rise". Gamasutra. August 20, 2008.

- ^ Leone (2015): "In some cases, developers take white label work simply because it's all they can get."

- ^ a b Leone, Matt (30 September 2015). "The secret developers of the video game industry". Polygon. Archived from the original on 1 October 2015.

- ^ Haske, Steve (15 October 2021). "Metroid Dread developer leaves names out of credits, ex-staffers say". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 19 October 2021.

Meanwhile, Japan has an entire unsung "support" industry known as "white label development" based around insistently anonymous studio work. Long-running outfits like Hyde and Tose contribute in secret to powerhouse franchises like Final Fantasy, Yakuza, and Resident Evil, among many others.

- ^ "2257本のゲーム などを 手掛けてきた国内最大規模の 受託開発メーカーに迫る" [The Story of Japan's biggest contract developer that has worked on 2257 different games]. Weekly Famitsū (in Japanese). 14 April 2017. (translation)

- ^ Kerr, Chris (26 April 2017). "Inside Tose Software, the biggest Japanese game dev you've never heard of". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on 29 April 2017.

- ^ Priestman, Chris (29 July 2015). "What Is HYDE, Inc. And What Are They Bringing To Red Ash?". Siliconera. Archived from the original on 11 April 2021.

- ^ Leone (2015): "Yanagihara says the roots of this approach run deep in Japanese culture, with many people preferring not to seek the limelight and many classic businesses working this way."

- ^ a b c Bates 2004, p. 241.

- ^ a b Bates 2004, p. 242.

- ^ Bates 2004, p. 246.