Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

PC game

View on Wikipedia

| Video games |

|---|

A personal computer game, or abbreviated PC game, also known as a computer game,[a] is a video game played on a personal computer (PC). The term PC game has been popularly used since the 1990s referring specifically to games on "Wintel" (Microsoft Windows software/Intel hardware) which has dominated the computer industry since.

Mainframe and minicomputer games are a precursor to personal computer games. Home computer games became popular following the video game crash of 1983. In the 1990s, PC games lost mass market traction to console games on the fifth generation such as the Sega Saturn, Nintendo 64 and PlayStation.[citation needed] They are enjoying a resurgence in popularity since the mid-2000s through digital distribution on online service providers.[1][2] Personal computers as well as general computer software are considered synonymous with IBM PC compatible systems; while mobile devices – smartphones and tablets, such as those running on Android or iOS platforms – are also PCs in the general sense as opposed to console or arcade machine. Historically, it also included games on systems from Apple Computer, Atari Corporation, Commodore International and others. Microsoft Windows utilizing Direct3D become the most popular operating system for PC games in the 2000s. Games utilizing 3D graphics generally require a form of graphics processing unit, and PC games have been a major influencing factor for the development and marketing of graphics cards. Emulators are able to play games developed for other platforms. The demoscene originated from computer game cracking.

The uncoordinated nature of the PC game market makes precisely assessing its size difficult.[1] PC remains the most important gaming platform with 60% of developers being most interested in developing a game for the platform and 66% of developers currently developing a game for PC.[3][better source needed] In 2018, the global PC games market was valued at about $27.7 billion.[4][better source needed] According to research data provided by Statista in 2020 there were an estimated 1.75 billion PC gamers worldwide, up from 1.5 billion PC gaming users in the previous year.[5][better source needed] Newzoo reported that the PC gaming sector was the third-largest category across all platforms as of 2016[update], with the console sector second-largest, and mobile gaming sector biggest. 2.2 billion video gamers generate US$101.1 billion in revenue, excluding hardware costs. "Digital game revenues will account for $94.4 billion or 87% of the global gaming market.[6][7][better source needed] The APAC region was estimated to generate $46.6 billion in 2016, or 47% of total global video game revenues (note, not only "PC" games). China alone accounts for half of APAC's revenues (at $24.4 billion), cementing its place as the largest video game market in the world, ahead of the US's anticipated market size of $23.5 billion.[citation needed]

History

[edit]Mainframes and minicomputers

[edit]

Bertie the Brain was one of the first game playing machines developed. It was built in 1950 by Josef Kates. It measured more than four meters tall, and was displayed at the Canadian National Exhibition that year.[8][non-primary source needed]

Although personal computers only became popular with the development of the microprocessor and microcomputer, computer gaming on mainframes and minicomputers had previously already existed. OXO, an adaptation of tic-tac-toe for the EDSAC, debuted in 1952. Another pioneer computer game was developed in 1961, when MIT students Martin Graetz and Alan Kotok, with MIT student Steve Russell, developed Spacewar! on a PDP-1 mainframe computer used for statistical calculations.[9]

The first generation of computer games were often text-based adventures or interactive fiction, in which the player communicated with the computer by entering commands through a keyboard. An early text-adventure, Adventure, was developed for the PDP-11 minicomputer by Will Crowther in 1976, and expanded by Don Woods in 1977.[10] By the 1980s, personal computers had become powerful enough to run games like Adventure, but by this time, graphics were beginning to become an important factor in games. Later games combined textual commands with basic graphics, as seen in the SSI Gold Box games such as Pool of Radiance, or The Bard's Tale, for example.

Early personal computer games

[edit]

By the late 1970s to early 1980s, games were developed and distributed through hobbyist groups and gaming magazines, such as Creative Computing and later Computer Gaming World. These publications provided game code that could be typed into a computer and played, encouraging readers to submit their own software to competitions.[11] Players could modify the BASIC source code of even commercial games.[12] Microchess was one of the first games for microcomputers which was sold to the public. First sold in 1977, Microchess eventually sold over 50,000 copies on cassette tape.

As with second-generation video game consoles at the time, early home computer game companies capitalized on successful arcade games at the time with ports or clones of popular arcade video games.[13][14] By 1982, the top-selling games for the Atari 8-bit computers were ports of Frogger and Centipede, while the top-selling game for the TI-99/4A was the Space Invaders clone TI Invaders.[13] That same year, Pac-Man was ported to the Atari 8-bit computers,[14] while Donkey Kong was licensed for the Coleco Adam.[15] In late 1981, Atari, Inc. attempted to take legal action against unauthorized Pac-Man clones, despite some of these predating Atari's exclusive rights to the home versions of Namco's game.[14][16] Thousands of children attended the 1982 West Coast Computer Faire to see computer games there, despite organizers warning that the convention "is designed for mature individuals".[17]

Industry crash and aftermath

[edit]As the American video game market became flooded with poor-quality cartridge games created by numerous companies attempting to enter the market, and overproduction of high-profile releases such as the Atari 2600 adaptations of Pac-Man and E.T. grossly underperformed, the popularity of personal computers for education rose dramatically. In 1983, American consumer interest in console video games dwindled to historical lows, as interest in games on personal computers rose.[18] The effects of the crash were largely limited to the console market, as established companies such as Atari posted record losses over subsequent years. Conversely, the home computer market boomed, as sales of low-cost color computers such as the Commodore 64 rose to record highs and developers such as Electronic Arts benefited from increasing interest in the platform.[18]

Growth of home computer games

[edit]The North American console market experienced a resurgence in the United States with the release of the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES). In Europe, computer gaming continued to boom for many years after.[18] Computers such as the ZX Spectrum and BBC Micro were successful in the European market, where the NES was not as successful despite its monopoly in Japan and North America. The only 8-bit console to have any success in Europe would be the Master System.[19] Meanwhile, in Japan, both consoles and computers became major industries, with the console market dominated by Nintendo and the computer market dominated by NEC's PC-88 (1981) and PC-98 (1982). A key difference between Western and Japanese computers at the time was the display resolution, with Japanese systems using a higher resolution of 640x400 to accommodate Japanese text, which in turn affected video game design and allowed more detailed graphics. Japanese computers were also using Yamaha's FM synth sound boards from the early 1980s.[20]

To enhance the immersive experience with their unrealistic graphics and electronic sound, early PC games included extras such as the peril-sensitive sunglasses that shipped with The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy or the science fiction novella included with Elite. These extras gradually became less common, but many games were still sold in the traditional oversized boxes that used to hold the extra "feelies". Today, such extras are usually found only in Special Edition versions of games, such as Battle chests from Blizzard.[21]

During the 16-bit era, the Amiga and Atari ST became popular in Europe, the Macintosh and IBM PC compatibles became popular in North America, while the PC-98, X68000, and FM Towns became popular in Japan. The Amiga, X68000 and FM Towns were capable of producing near arcade-quality hardware sprite graphics and sound quality when they first released in the mid-to-late 1980s.[20]

Growth of IBM PC compatible games

[edit]Among launch titles for the IBM Personal Computer (PC) in 1981 was Microsoft Adventure, which IBM described as bringing "players into a fantasy world of caves and treasures".[22] BYTE that year stated that the computer's speed and sophistication made it "an excellent gaming device", and IBM and others sold games like Microsoft Flight Simulator. The PC's CGA graphics and speaker sound were poor, however, and most customers bought the powerful but expensive computer for business.[23][24] One ComputerLand owner estimated in 1983 that a quarter of corporate executives with computers "have a game hidden somewhere in their drawers",[25] and InfoWorld in 1984 reported that "in offices all over America (more than anyone realizes) executives and managers are playing games on their computers",[26][27] but software companies found selling games for the PC difficult; an observer said that year that Flight Simulator had sold hundreds of thousands of copies because customers with corporate PCs could claim that it was a "simulation".[28]

From mid-1985, however, what Compute! described as a "wave" of inexpensive IBM PC clones from American and Asian companies, such as the Tandy 1000 and the Leading Edge Model D, caused prices to decline; by the end of 1986, the equivalent to a $1600 real IBM PC with 256K RAM and two disk drives cost as little as $600, lower than the price of the Apple IIc. Consumers began purchasing DOS computers for the home in large numbers. While often purchased to do work on evenings and weekends, clones' popularity caused consumer-software companies to increase the number of IBM-compatible products, including those developed specifically for the PC as opposed to porting from other computers. Bing Gordon of Electronic Arts reported that customers used computers for games more than one fifth of the time whether purchased for work or a hobby, with many who purchased computers for other reasons finding PC games "a pretty satisfying experience".[29]

PC game sales rose by 198% year over year in the first half of 1987, compared to 57% for the market overall. The formerly business-only computer had become the largest and fastest-growing, and most important platform for computer game companies. More than a third of games sold in North America were for the PC, twice as many as those for the Apple II and even outselling those for the Commodore 64.[27][30] By 1988 Computer Gaming World agreed with Joel Billings of Strategic Simulations that an inexpensive clone with EGA graphics was superior for games.[31][32] The Tandy 1000's enhanced graphics, sound, and built-in joystick ports made it the best platform for IBM PC-compatible games before the VGA era.[24]

By 1988, the enormous popularity of the Nintendo Entertainment System had greatly affected the computer-game industry. A Koei executive claimed that "Nintendo's success has destroyed the [computer] software entertainment market". A Mindscape executive agreed, saying that "Unfortunately, its effect has been extremely negative. Without question, Nintendo's success has eroded software sales. There's been a much greater falling off of disk sales than anyone anticipated." A third attributed the end of growth in sales of the Commodore 64 to the console, and Trip Hawkins called Nintendo "the last hurrah of the 8-bit world". Experts were unsure whether it affected 16-bit computer games,[33] but games lost shelf space at computer software stores, and many of the hundreds of computer-game companies went out of business. Hawkins said that while foreign videogame competition increased, "there's an increase in product supply without an increase in demand".[34] He in 1990 had to deny rumors that Electronic Arts would withdraw from computers and only produce console games.[35] By 1993, ASCII Entertainment reported at a Software Publishers Association conference that the market for console games ($5.9 billion in revenue) was 12 times that of the computer-game market ($430 million).[36]

However, computer games did not disappear. The industry hoped that the CD-ROM and other optical storage technology would increase computers' user friendliness and allow for more sophisticated games.[34] By 1989, Computer Gaming World reported that "the industry is moving toward heavy use of VGA graphics".[37] While some games were advertised with VGA support at the start of the year, they usually supported EGA graphics through VGA cards. By the end of 1989, however, most publishers moved to supporting at least 320x200 MCGA, a subset of VGA.[38] VGA gave the PC graphics that outmatched the Amiga. Increasing adoption of the computer mouse, driven partially by the success of adventure games such as the highly successful King's Quest series, and high resolution bitmap displays allowed the industry to include increasingly high-quality graphical interfaces in new releases.

Further improvements to game artwork and audio were made possible with the introduction of FM synthesis sound. Yamaha began manufacturing FM synth boards for computers in the early-mid-1980s, and by 1985, the NEC and FM-7 computers had built-in FM sound.[20] The first PC sound cards, such as AdLib's Music Synthesizer Card, soon appeared in 1987. These cards allowed IBM PC compatible computers to produce complex sounds using FM synthesis, where they had previously been limited to simple tones and beeps. However, the rise of the Creative Labs Sound Blaster card, released in 1989, which featured much higher sound quality due to the inclusion of a PCM channel and digital signal processor, led AdLib to file for bankruptcy by 1992. Also in 1989, the FM Towns computer included built-in PCM sound, in addition to a CD-ROM drive and 24-bit color graphics.[20]

In the late 80s and throughout the entire 1990s decade, DOS was one of the most popular gaming platforms in regions where it was officially sold.[39]

By 1990, DOS was 65% of the computer-game market, with the Amiga at 10%; all other computers, including the Apple Macintosh, were below 10% and declining. Although both Apple and IBM tried to avoid customers associating their products with "game machines", the latter acknowledged that VGA, audio, and joystick options for its PS/1 computer were popular.[40] In 1991, id Software produced an early first-person shooter, Hovertank 3D, which was the company's first in their line of highly influential games in the genre. There were also several other companies that produced early first-person shooters, such as Arsys Software's Star Cruiser,[41] which featured fully 3D polygonal graphics in 1988,[42] and Accolade's Day of the Viper in 1989. Id Software went on to develop Wolfenstein 3D in 1992, which helped to popularize the genre, kick-starting a genre that would become one of the highest-selling in modern times.[43] The game was originally distributed through the shareware distribution model, allowing players to try a limited part of the game for free but requiring payment to play the rest, and represented one of the first uses of texture mapping graphics in a popular game, along with Ultima Underworld.[44]

In December 1992, Computer Gaming World reported that DOS accounted for 82% of computer-game sales in 1991, compared to Macintosh's 8% and Amiga's 5%. In response to a reader's challenge to find a DOS game that played better than the Amiga version the magazine cited Wing Commander and Civilization, and added that "The heavy MS-DOS emphasis in CGW merely reflects the realities of the market".[45] A self-reported Computer Gaming World survey in April 1993 similarly found that 91% of readers primarily used IBM PCs and compatibles for gaming, compared to 6% for Amiga, 3% for Macintosh, and 1% for Atari ST,[46] while a Software Publishers Association study found that 74% of personal computers were IBMs or compatible, 10% Macintosh, 7% Apple II, and 8% other. 51% of IBM or compatible had 386 or faster CPUs.[36]

By 1992, DOS games such as Links 386 Pro supported Super VGA graphics.[47] While leading Sega and Nintendo console systems kept their CPU speed at 3–7 MHz, the 486 PC processor ran much faster, allowing it to perform many more calculations per second. The 1993 release of Doom on the PC was a breakthrough in 3D graphics, and was soon ported to various game consoles in a general shift toward greater realism.[48] Computer Gaming World reiterated in 1994, "we have to advise readers who want a machine that will play most of the games to purchase high-end MS-DOS machines".[49]

By 1993, PC floppy disk games had a sales volume equivalent to about one-quarter that of console game ROM cartridge sales. A hit PC game typically sold about 250,000 disks at the time, while a hit console game typically sold about 1 million cartridges.[50]

By spring 1994, an estimated 24 million US homes (27% of households) had a personal computer. 48% played games on their computer; 40% had the 486 CPU or higher; 35% had CD-ROM drives; and 20% had a sound card.[51] Another survey found that an estimated 2.46 million multimedia computers had internal CD-ROM drives by the end of 1993, an increase of almost 2,000%. Computer Gaming World reported in April 1994 that some software publishers planned to only distribute on CD as of 1995.[52] CD-ROM had much larger storage capacity than floppies, helped reduce software piracy, and was less expensive to produce. Chris Crawford warned that it was "a data-intensive technology, not a process-intensive one", tempting developers to emphasize the quantity of digital assets like art and music over the quality of gameplay; Computer Gaming World wrote in 1993 that "publishers may be losing their focus". While many companies used the additional storage to release poor-quality shovelware collections of older software, or "enhanced" versions of existing ones[53]—often with what the magazine mocked as "amateur acting" in the added audio and video[52]—new games such as Myst included many more assets for a richer game experience.

Many companies sold "multimedia upgrade kits" that bundled CD drives, sound cards, and software during the mid-1990s, but device drivers for the new peripherals further depleted scarce RAM.[54] By 1993, PC games required much more memory than other software, often consuming all of conventional memory, while device drivers could go into upper memory with DOS memory managers. Players found modifying CONFIG.SYS and AUTOEXEC.BAT files for memory management cumbersome and confusing, and each game needed a different configuration. (The game Les Manley in: Lost in L.A. satirizes this by depicting two beautiful women exhaust the hero in bed, by requesting that he again explain the difference between extended and expanded memory.) Computer Gaming World provided technical assistance to its writers to help install games for review,[55] and published sample configuration files.[56] The magazine advised non-technical gamers to purchase commercial memory managers like QEMM and 386MAX[54] and criticized nonstandard software like Origin Systems's "infamous late and unlamented Voodoo Memory Manager",[57] which used unreal mode.

Contemporary PC gaming

[edit]

By 1996, the growing popularity of Microsoft Windows simplified device driver and memory management. The success of 3D console titles such as Super Mario 64 and Tomb Raider increased interest in hardware accelerated 3D graphics on PCs, and soon resulted in attempts to produce affordable products with the ATI Rage, Matrox Mystique, S3 ViRGE, and Rendition Vérité.[58] As 3D graphics libraries such as DirectX and OpenGL matured and knocked proprietary interfaces out of the market, these platforms gained greater acceptance in the market, particularly with their demonstrated benefits in games such as Unreal.[59] However, major changes to the Microsoft Windows operating system, by then the market leader, made many older DOS-based games unplayable on Windows NT, and later, Windows XP (without using an emulator, such as DOSBox).[60][61]

The faster graphics accelerators and improving CPU technology resulted in increasing levels of realism in computer games. During this time, the improvements introduced with products such as ATI's Radeon R300 and NVidia's GeForce 6 series have allowed developers to increase the complexity of modern game engines. PC gaming currently tends strongly toward improvements in 3D graphics.[62]

Unlike the generally accepted push for improved graphical performance, the use of physics engines in computer games has become a matter of debate since announcement and 2005 release of the nVidia PhysX PPU, ostensibly competing with middleware such as the Havok physics engine. Issues such as difficulty in ensuring consistent experiences for all players,[63] and the uncertain benefit of first generation PhysX cards in games such as Tom Clancy's Ghost Recon Advanced Warfighter and City of Villains, prompted arguments over the value of such technology.[64][65]

Similarly, many game publishers began to experiment with new forms of marketing. Chief among these alternative strategies is episodic gaming, an adaptation of the older concept of expansion packs, in which game content is provided in smaller quantities but for a proportionally lower price. Titles such as Half-Life 2: Episode One and Episode Two took advantage of the idea, with mixed results rising from concerns for the amount of content provided for the price.[66]

Platform characteristics

[edit]The defining characteristic of the PC platform is the absence of centralized control, an open platform; all other gaming platforms (except Android devices, to an extent) are owned and administered by a single group.

PCs may possess varying processing resources of video gaming systems. Game developers may integrate options to adjust screen resolution, framerate,[67] and anti-aliasing. Increased draw distance and NPCs amount is also possible in open world games.[68][69] The most common forms of input are the mouse/keyboard combination and gamepads, though touchscreens and motion controllers are also available. The mouse in particular lends players of first-person shooter and real-time strategy games on PC great speed and accuracy.[70] Users may use third-party peripherals.[citation needed]

This section is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (April 2023) |

The advantages of openness include:

- Reduced software cost

- Prices are kept down by competition and the absence of platform-holder fees. Games and services are cheaper at every level, and many are free.[71][72]

- Increased flexibility

- PC games decades old can be played on modern systems, through emulation software if need be. Conversely, newer games can often be run on older systems by reducing the games' fidelity, scale or both.

- Increased innovation

- One does not need to ask for permission to release or update a PC game or to modify an existing one, and the platform's hardware and software are constantly evolving. These factors make PC the centre of both hardware and software innovation. By comparison, closed platforms tend to remain much the same throughout their lifespan.[2][73]

There are also disadvantages, including:

- Increased complexity

- A PC is a general-purpose tool. Its inner workings are exposed to the owner, and misconfiguration can create enormous problems. Hardware compatibility issues are also possible. Game development is complicated by the wide variety of hardware configurations; developers may be forced to limit their design to run with sub-optimum PC hardware in order to reach a larger PC market, or add a range graphical and other settings to adjust for playability on individual machines, requiring increased development, test, and customer support resources.[citation needed]

- Increased hardware cost

- PC components are generally sold individually for profit (even if one buys a pre-built machine), whereas the hardware of closed platforms is mass-produced as a single unit and often sold at a smaller profit, or even a loss (with the intention of making profit instead in online service fees and developer kit profits).[72]

- Reduced security

- It is difficult, and in most situations ultimately impossible, to control the way in which PC hardware and software is used. This leads to far more software piracy and cheating than closed platforms suffer from.[74]

Modifications

[edit]The openness of the PC platform allows players to edit or modify their games and distribute the results over the Internet as "mods". A healthy mod community greatly increases a game's longevity and the most popular mods have driven purchases of their parent game to record heights.[75] It is common for professional developers to release the tools they use to create their games (and sometimes even source code[76][77]) in order to encourage modding,[78] but if a game is popular enough mods generally arise even without official support.[79]

Mods can compete with official downloadable content however, or even outright redistribute it, and their ability to extend the lifespan of a game can work against its developers' plans for regular sequels. As game technology has become more complex, it has also become harder to distribute development tools to the public.[80]

Modding has a different connotation on consoles which are typically restricted much more heavily. As publicly released development tools are rare, console mods usually refer to hardware alterations designed to remove restrictions.[81]

Digital distribution services

[edit]PC games are sold predominantly through the Internet, with buyers downloading their new purchase directly to their computer.[2][82] This approach allows smaller independent developers to compete with large publisher-backed games[1][83] and avoids the speed and capacity limits of the optical discs which most other gaming platforms rely on.[84][85]

Valve released the Steam platform for Windows computers in 2003 as a means to distribute Valve-developed video games such as Half-Life 2. It would later see release on the Mac OS X operating system in 2010 and was released on Linux in 2012. By 2011, it controlled 70% of the market for downloadable PC games, with a userbase of about 40 million accounts.[86][87] Origin, a new version of the Electronic Arts online store, was released in 2011 in order to compete with Steam and other digital distribution platforms on the PC.[88][non-primary source needed] The period between 2004 and now saw the rise of many digital distribution services on PC, such as Amazon Digital Services, GameStop, GFWL, EA Store, Direct2Drive, GOG.com, and GamersGate.

Digital distribution also slashes the cost of circulation, eliminates stock shortages, allows games to be released worldwide at no additional cost, and allows niche audiences to be reached with ease.[89] However, most digital distribution systems create ownership and customer rights issues by storing access rights on distributor-owned computers. Games confer with these computers over the Internet before launching. This raises the prospect of purchases being lost if the distributor goes out of business or chooses to lock the buyer's account, and prevents resale (the ethics of which are a matter of debate).

Valve does not release any sales figures on its Steam service, instead it only provides the data to companies with games on Steam,[90][91] which they cannot release without permission due to signing a non-disclosure agreement with Valve.[92][93] However, Stardock, the previous owner of competing platform Impulse, estimated that, as of 2009, Steam had a 70% share of the digital distribution market for video games.[94] In early 2011, Forbes reported that Steam sales constituted 50–70% of the $4 billion market for downloaded PC games and that Steam offered game producers gross margins of 70% of purchase price, compared with 30% at retail.[86][95]

PC gaming technology

[edit]

Hardware

[edit]Modern computer games place great demand on the computer's hardware, often requiring a fast central processing unit (CPU) to function properly. CPU manufacturers historically relied mainly on increasing clock rates to improve the performance of their processors, but had begun to move steadily towards multi-core CPUs by 2005. These processors allow the computer to simultaneously process multiple tasks, called threads, allowing the use of more complex graphics, artificial intelligence and in-game physics.[62][96]

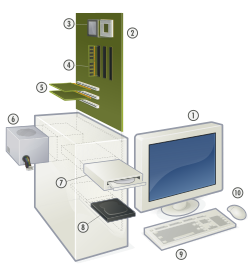

Similarly, 3D games often rely on a powerful graphics processing unit (GPU), which accelerates the process of drawing complex scenes in realtime. GPUs may be an integrated part of the computer's motherboard, the most common solution in laptops,[97] or come packaged with a discrete graphics card with a supply of dedicated Video RAM, connected to the motherboard through either an AGP or PCI Express port. It is also possible to use multiple GPUs in a single computer, using technologies such as NVidia's Scalable Link Interface and ATI's CrossFire.

Sound cards are also available to provide improved audio in computer games. These cards provide improved 3D audio and provide audio enhancement that is generally not available with integrated alternatives, at the cost of marginally lower overall performance.[98] The Creative Labs Sound Blaster line was for many years the de facto standard for sound cards, although its popularity dwindled as PC audio became a commodity on modern motherboards.

Physics processing units (PPUs), such as the Nvidia PhysX (formerly AGEIA PhysX) card, are also available to accelerate physics simulations in modern computer games. PPUs allow the computer to process more complex interactions among objects than is achievable using only the CPU, potentially allowing players a much greater degree of control over the world in games designed to use the card.[97]

Virtually all personal computers use a keyboard and mouse for user input, but there are exceptions. During the 1990s, before the keyboard and mouse combination had become the method of choice for PC gaming input peripherals, there were other types of peripherals such as the Mad Catz Panther XL, the First-Person Gaming Assassin 3D, and the Mad Catz Panther, which combined a trackball for looking / aiming, and a joystick for movement. Other common gaming peripherals are a headset for faster communication in online games, joysticks for flight simulators, steering wheels for driving games and gamepads for console-style games.

Software

[edit]Computer games also rely on third-party software such as an operating system (OS), device drivers, libraries and more to run. Today, the vast majority of computer games are designed to run on the Microsoft Windows family of operating systems. Whereas earlier games written for DOS would include code to communicate directly with hardware, today application programming interfaces (APIs) provide an interface between the game and the OS, simplifying game design. Microsoft's DirectX is an API that is widely used by today's computer games to communicate with sound and graphics hardware. OpenGL is a cross-platform API for graphics rendering that is also used. The version of the graphics card's driver installed can often affect game performance and gameplay. In late 2013, AMD announced Mantle, a low-level API for certain models of AMD graphics cards, allowing for greater performance compared to software-level APIs such as DirectX, as well as simplifying porting to and from the PlayStation 4 and Xbox One consoles, which are both built upon AMD hardware.[99] It is not unusual for a game company to use a third-party game engine, or third-party libraries for a game's AI or physics.

Types of gaming

[edit]Local area network gaming

[edit]Multiplayer gaming was largely limited to local area networks (LANs) before cost-effective broadband Internet access became available, due to their typically higher bandwidth and lower latency than the dial-up services of the time. These advantages allowed more players to join any given computer game, but have persisted today because of the higher latency of most Internet connections and the costs associated with broadband Internet.

LAN gaming typically requires two or more personal computers, a router and sufficient networking cables to connect every computer on the network. Additionally, each computer must have its own copy (or spawn copy) of the game in order to play. Optionally, any LAN may include an external connection to the Internet.

Online games

[edit]Online multiplayer games have achieved popularity largely as a result of increasing broadband adoption among consumers. Affordable high-bandwidth Internet connections allow large numbers of players to play together, and thus have found particular use in massively multiplayer online role-playing games, Tanarus and persistent online games such as World War II Online.

Although it is possible to participate in online computer games using dial-up modems, broadband Internet connections are generally considered necessary in order to reduce the latency or "lag" between players. Such connections require a broadband-compatible modem connected to the personal computer through a network interface card (generally integrated onto the computer's motherboard), optionally separated by a router. Online games require a virtual environment, generally called a "game server". These virtual servers inter-connect gamers, allowing real time, and often fast-paced action. To meet this subsequent need, Game Server Providers (GSP) have become increasingly more popular over the last half decade.[when?] While not required for all gamers, these servers provide a unique "home", fully customizable, such as additional modifications, settings, etc., giving the end gamers the experience they desire. Today there are over 510,000 game servers hosted in North America alone.[100][non-primary source needed]

Emulation

[edit]Emulation software, used to run software without the original hardware, are popular for their ability to play legacy video games without the platform for which they were designed. The operating system emulators include DOSBox, a DOS emulator which allows playing games developed originally for this operating system and thus not compatible with a modern-day OS. Console emulators such as Nestopia and MAME are relatively commonplace, although the complexity of modern consoles such as the Xbox or PlayStation makes them far more difficult to emulate, even for the original manufacturers.[101] The most technically advanced consoles that can currently be successfully emulated for commercial games on PC are the PlayStation 2 using PCSX2, and the Nintendo Wii U using the Cemu emulator. A PlayStation 3 emulator named RPCS3 is in development. Most emulation software mimics a particular hardware architecture, often to an extremely high degree of accuracy. This is particularly the case with classic home computers such as the Commodore 64, whose software often depends on highly sophisticated low-level programming tricks invented by game programmers and the demoscene.

Other projects aim to bring compatibility of older games and its features back to modern platforms such as WineVDM (for running 16-bit games on 64-bit Windows), nGlide (for enabling Glide (API) to other video cards), IPXWrapper (for enabling IPX/SPX based LAN play).

Controversy

[edit]PC games have long been a source of controversy, largely due to the depictions of violence that has become commonly associated with video games in general, with much of the criticism stemming from the fact that the PC gaming industry is not as regulated as on other platforms. The debate surrounds the influence of objectionable content on the social development of minors, with organizations such as the American Psychological Association concluding that video game violence increases children's aggression,[102] a concern that prompted a further investigation by the Centers for Disease Control in September 2006.[103] Industry groups have responded by noting the responsibility of parents in governing their children's activities, while attempts in the United States to control the sale of objectionable games have generally been found unconstitutional.[104]

Video game addiction is another cultural aspect of gaming to draw criticism as it can have a negative influence on health and on social relations. The problem of addiction and its health risks seems to have grown with the rise of massively multiplayer online role playing games (MMORPGs).[105] Alongside the social and health problems associated with computer game addiction have grown similar worries about the effect of computer games on education.[106]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Computer game may also be a synonym for video game.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Stuart, Keith (January 27, 2010). "Back to the bedroom: how indie gaming is reviving the Britsoft spirit". The Guardian. Retrieved November 8, 2012.

- ^ a b c "Japan fights back". The Economist. November 17, 2012.

- ^ "The Most Important Gaming Platforms in 2019". Statista. March 18, 2019.

- ^ "Global PC Games Market Analysis 2015-2019 with Forecasting to 2030: Revenue Breakdowns for Shooter, Action, Sport Games, Role-Playing, Adventure, Racing, Fighting, Strategy & Other Genres - ResearchAndMarkets.com". Business Wire. November 7, 2019.

- ^ "Number of PC gaming users worldwide from 2008 to 2024". Statista. November 24, 2022.

- ^ "The Global Games Market 2017 — Per Region & Segment — Newzoo".

- ^ "New Gaming Boom: Newzoo Ups Its 2017 Global Games Market Estimate to $116.0Bn Growing to $143.5Bn in 2020 | Newzoo". Newzoo. Retrieved December 15, 2017.

- ^ "What was the first video game, who invented it and why". Plarium. May 15, 2018. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- ^ Levy, Steven (1984). Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution. Anchor Press/Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-19195-2.

- ^ Jerz, Dennis (2007). "Somewhere Nearby is Colossal Cave: Examining Will Crowther's Original 'Adventure' in Code and in Kentucky". Digital Humanities Quarterly. 001 (2). Retrieved September 29, 2007.

- ^ "Computer Gaming World's RobotWar Tournament" (PDF). Computer Gaming World. October 1982. p. 17. Retrieved October 22, 2006.

- ^ Proctor, Bob (January 1982). "Tanktics: Review and Analysis". Computer Gaming World. pp. 17–20.

- ^ a b Earl g. Graves, Ltd (December 1982), "Cash In On the Video Game Craze", Black Enterprise, vol. 12, no. 5, pp. 41–2, ISSN 0006-4165, retrieved May 1, 2011

- ^ a b c John Markoff (November 30, 1981), "Atari acts in an attempt to scuttle software pirates", InfoWorld, vol. 3, no. 28, pp. 28–9, ISSN 0199-6649, retrieved May 1, 2011

- ^ Charles W. L. Hill & Gareth R. Jones (2007), Strategic management: an integrated approach (8 ed.), Cengage Learning, ISBN 978-0-618-89469-7

- ^ Mace, Scott (April 12, 1982). "Zenith working on 16-bit micros". InfoWorld. pp. 1, 4. Retrieved March 16, 2025.

- ^ Freiberger, Paul; Dvorak, John C. (April 12, 1982). "West Coast Computer Faire draws 40,000 people". InfoWorld. pp. 1, 6–7. Retrieved March 16, 2025.

- ^ a b c "Player 3 Stage 6: The Great Videogame Crash". April 7, 1999. Archived from the original on January 5, 2013. Retrieved August 16, 2006.

"The third member of the deadly troika that lays the videogame industry low is the home computer boom currently in full swing by 1984

- ^ Travis Fahs (April 21, 2009). "IGN Presents the History of SEGA: World War". IGN. p. 3. Retrieved May 21, 2011.

- ^ a b c d John Szczepaniak. "Retro Japanese Computers: Gaming's Final Frontier Retro Japanese Computers". Hardcore Gaming 101. Retrieved March 29, 2011. Reprinted from Retro Gamer, 2009

- ^ Varney, Allen. "Feelies". Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved September 24, 2006.

- ^ Bricklin, Dan. "IBM PC Announcement 1981". Dan Bricklin's Web Site. Retrieved March 6, 2018.

- ^ Williams, Gregg (December 1981). "New Games New Directions". BYTE. pp. 6–10. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

- ^ a b Loguidice, Bill; Barton, Matt (2014). Vintage Game Consoles: An Inside Look at Apple, Atari, Commodore, Nintendo, and the Greatest Gaming Platforms of All Time. CRC Press. pp. 85, 89–92, 96–97. ISBN 978-1135006518.

- ^ Solomon, Abby (October 1983). "Games Businesspeople Play". Inc.

- ^ Mace, Scott (April 2, 1984). "Games with windows". InfoWorld. p. 56. Retrieved February 10, 2015.

- ^ a b Shannon, L. R. (August 25, 1987). "Finally, the Right Stuff". Peripherals. The New York Times. pp. C8. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 14, 2025.

- ^ "The CGW Computer Game Conference". Computer Gaming World (panel discussion). October 1984. p. 30. Retrieved October 31, 2013.

- ^ Halfhill, Tom R. (December 1986). "The MS-DOS Invasion / IBM Compatibles Are Coming Home". Compute!. p. 32. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- ^ Keiser, Gregg (June 1988). "MS-DOS Takes Charge of Fun Software". Compute!. p. 81. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

- ^ Brooks, M. Evan (November 1987). "Titans of the Computer Gaming World / MicroProse". Computer Gaming World. p. 16. Retrieved November 2, 2013.

- ^ Proctor, Bob (March 1988). "Titans of the Computer Gaming World / SSI". Computer Gaming World. p. 36. Retrieved November 2, 2013.

- ^ Ferrell, Keith (July 1989). "Just Kids' Play or Computer in Disguise?". Compute!. p. 28. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

- ^ a b "Optical Drives Could Boost Entertainment Software". BYTE. February 1989. pp. 16–17. Retrieved October 8, 2024.

- ^ "Electronic Arts Reaffirms Commitment to Disk-Based Software". Computer Gaming World. March 1990. p. 14. Archived from the original on April 5, 2016. Retrieved November 15, 2013.

- ^ a b Wilson, Johnny L. (June 1993). "The Software Publishing Association Spring Symposium 1993". Computer Gaming World. p. 96. Retrieved July 7, 2014.

- ^ "The Shadow of Your Style / New Directions at the Consumer Electronics Show". Computer Gaming World. July 1989. p. 4. Retrieved November 3, 2013.

- ^ Sipe, Russell (November 1992). "3900 Games Later..." Computer Gaming World. p. 8. Retrieved July 4, 2014.

- ^ Jennings, Peter; Brewster, Todd (November 1998). The Century (1st ed.). New York: Doubleday. p. 551. ISBN 0-385-48327-9.

- ^ "Fusion, Transfusion or Confusion / Future Directions In Computer Entertainment". Computer Gaming World. December 1990. p. 26. Retrieved November 16, 2013.

- ^ "Star Cruiser". AllGame. Archived from the original on January 1, 2014.

- ^ スタークルーザー (translation), 4Gamer.net

- ^ Cifaldi, Frank (February 21, 2006). "Analysts: FPS 'Most Attractive' Genre for Publishers". Archived from the original on June 27, 2022. Retrieved August 17, 2006.

- ^ James, Wagner. "Masters of "Doom"". Archived from the original on August 13, 2007. Retrieved September 23, 2006.

- ^ "Letters". Computer Gaming World. December 1992. p. 122. Retrieved July 5, 2014.

- ^ "What You've Been Playing Lately". Computer Gaming World. April 1993. p. 176. Retrieved July 7, 2014.

- ^ McDonald, T. Liam (November 1992). "Links 386 Pro from Access". Computer Gaming World. p. 72. Retrieved July 4, 2014.

- ^ "Console history". Retrieved September 23, 2006.

- ^ "Sound Philosophy". Letters from Paradise. Computer Gaming World. January 1994. pp. 120, 122.

- ^ "Microtimes". Microtimes. Vol. 10. BAM Publications, Incorporated. July 1993. p. 74.

But the reality is, today's business is cartridge business. The difference in volume is about four to one per title. With exceptions—a Falcom 3.0 will sell as much as a cartridge title would out in the open market. But even a hit title in the floppy disk market is a quarter million copies. (Cartridge game) Street Fighter II sold nine million copies worldwide.

- ^ "Software Publishing Association Unveils New Data". Read.Me. Computer Gaming World. May 1994. p. 12.

- ^ a b "Invasion Of The Data Stashers". Computer Gaming World. April 1994. pp. 20–42.

- ^ "Forging Ahead or Fit to be Smashed?". Computer Gaming World. April 1993. p. 24. Retrieved July 6, 2014.

- ^ a b Weksler, Mike (June 1994). "CDs On A ROMpage". Computer Gaming World. pp. 36–40.

- ^ Weksler, Mike (June 1993). "Memory Management and System Configuration for MS-DOS Games". Computer Gaming World. p. 99. Retrieved July 7, 2014.

- ^ "Load For Bear". Computer Gaming World. January 1994. p. 34.

- ^ Wilson, Johnny L. (December 1993). "The Sub-Standard In Computer software". Computer Gaming World (editorial). p. 10. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ "PC Goes 3D". Next Generation. No. 26. Imagine Media. February 1997. pp. 54–63.

- ^ Shamma, Tahsin. Review of Unreal, Gamespot.com, June 10, 1998.

- ^ Durham, Joel Jr. (May 14, 2006). "Getting Older Games to Run on Windows XP". Microsoft. Archived from the original on April 20, 2007. Retrieved September 22, 2006.

- ^ "Run Older Programs on Windows XP". Microsoft.

- ^ a b Necasek, Michal (October 30, 2006). "Brief Glimpse into the Future of 3D Game Graphics". Archived from the original on October 11, 2011. Retrieved September 23, 2006.

- ^ Reimer, Jeremy (May 14, 2006). "Tim Sweeney ponders the future of physics cards". Retrieved August 22, 2006.

- ^ Shrout, Ryan (May 2, 2006). "AGEIA PhysX PPU Videos – Ghost Recon and Cell Factor". Archived from the original on September 29, 2010. Retrieved August 22, 2006.

- ^ Smith, Ryan (September 7, 2006). "PhysX Performance Update: City of Villains". Archived from the original on August 8, 2010. Retrieved September 13, 2006.

- ^ "Half Life 2: Episode One for PC Review". June 2006. Archived from the original on September 24, 2009. Retrieved September 2, 2006.

- ^ Ivan, Tom (June 20, 2011). "Console Battlefield 3 is 720p, 30fps. DICE explains". Computer and Video Games.

- ^ Warner, Mark (November 23, 2011). "Tweaking Skyrim Image Quality". HardOCP. Archived from the original on September 17, 2019. Retrieved February 24, 2012.

- ^ "DICE on cutting Battlefield 3 console content: 'We're not evil or stupid'". Computer and Video Games. July 26, 2011.

- ^ Joe Fielder (May 12, 2000). "StarCraft 64". Gamespot.com. Retrieved August 19, 2006.

- ^ Sweeny, Tim (2007). "Next-Gen podcast". Next Generation Magazine podcast. Archived from the original on May 14, 2013. Retrieved February 23, 2012.

We've been developing games that are community-based for more than ten years now, ever since the original Unreal and Unreal Tournament. We've had games that have had free online gameplay, free server lists, and in 2003 we shipped a game with in-game voice support, and a lot of features that gamers have now come to expect on the PC platform. A lot of these things are now features that Microsoft is planning to charge for.

- ^ a b Lane, Rick (December 13, 2011). "Is PC Gaming Really More Expensive Than Consoles?". IGN. Archived from the original on December 13, 2011.

- ^ Bertz, Matt (March 13, 2010). "Valve and Blizzard Defend PC Platform, Diss Console Flexiblity". Game Informer. Archived from the original on April 25, 2013. Retrieved February 23, 2012.

- ^ Ghazi, Koroush (December 2010). "PC Game Piracy Examined". TweakGuides.com. Archived from the original on February 6, 2012. Retrieved February 23, 2012.

- ^ Usher, William (July 1, 2012). "DayZ Helps Arma 2 Rack Up More Than 300,000 In Sales". Cinema Blend.

- ^ "Alien Swarm Game & Source SDK Release Coming Monday". Valve. July 16, 2010.

- ^ "Quake 3 Source Code Released". August 2005. Retrieved October 22, 2006.

- ^ "Red Orchestra dev on mod tools: "I never understand why companies effectively block people from doing that stuff."". PCGamesN. October 8, 2012.

- ^ Smith, Adam (October 7, 2011). "Mods And Ends: Grand Theft Auto IV". Rock, Paper, Shotgun.

- ^ Kalms, Mikael (September 20, 2010). "So how about modtools?". Electronic Arts. Archived from the original on September 23, 2010.

- ^ "Judge deems PS2 mod chips illegal in UK". The Register. July 2004. Retrieved September 22, 2006.

- ^ "2012 Essential facts About the computer and Video game industry" (PDF). Entertainment Software Association. March 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 2, 2013.

- ^ Garr, Brian (April 17, 2011). "Download distribution opening new doors for independent game developers". Statesman.com. Archived from the original on April 21, 2011.

- ^ Kuchera, Ben (January 17, 2007). "Is Blu-ray really a good medium for games?". Ars Technica.

- ^ "Rage Will Look Worse on 360 Due to Compression; Doom 4 and Rage Not Likely for Digital Distribution". Shacknews. August 1, 2008.

- ^ a b Chiang, Oliver. "The Master of Online Mayhem". Forbes. Retrieved February 14, 2011.

- ^ "40 Million Active Gamers on Steam Mark". Gaming Bolt. January 6, 2012. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- ^ "PDF E3 2011 Investor Presentation". Electronic Arts. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 10, 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ Senior, Tom (July 6, 2011). "Paradox sales are 90% digital, "we don't really need retailers any more" says CEO". PC Gamer. Archived from the original on January 14, 2013.

- ^ "Valve: no Steam data for digital sales charts". April 21, 2011.

- ^ Parfitt, Ben (April 21, 2011). "Digital charts won't pick up Steam | Games industry news | MCV". MCV. Mcvuk.com. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- ^ Kuchera, Ben (July 2, 2012). "The PA Report – Why it's time to grow up and start ignoring the monthly NPD reports". Penny-arcade.com. Archived from the original on March 6, 2013. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- ^ "Garry's Mod Breaks 1 Million Sold, First Peek At Sales Chart – Voodoo Extreme". Ve3d.ign.com. Archived from the original on May 30, 2013. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- ^ Graft, Kris (November 19, 2009). "Stardock Reveals Impulse, Steam Market Share Estimates". Gamasutra. Retrieved November 21, 2009.

- ^ Periera, Chris (January 6, 2012). "Steam Experiences Another Year of Sales Growth in 2011". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on May 26, 2012. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ^ "Xbox 360 designed to be unhackable". October 2005. Archived from the original on May 23, 2010. Retrieved September 22, 2006.

- ^ a b "Platform Trends: Mobile Graphics Heat Up". December 2005. Retrieved October 22, 2006.

- ^ "X-Fi and the Elite Pro: SoundBlaster's Return to Greatness". August 2005. Archived from the original on January 17, 2013. Retrieved October 22, 2006.

- ^ "AMD's Mantle API Gives Devs Direct Hardware Control". September 26, 2013.

- ^ "Steam: Game and Player Statistics". store.steampowered.com.

- ^ "Xbox 360 Review". November 2005. Retrieved September 12, 2006.

- ^ American Psychological Association. "Violent Video Games – Psychologists Help Protect Children from Harmful Effects". Archived from the original on August 3, 2008.

- ^ "Senate bill mandates CDC investigation into video game violence". September 2006. Retrieved September 19, 2006.

- ^ "Judge rules against Louisiana video game law". August 2006. Retrieved September 2, 2006.

- ^ "Detox For Video Game Addiction?". CBS News. July 2006. Retrieved September 12, 2006.

- ^ "Tom Maher discusses the effects of computer game addiction on classroom teaching". dystalk.com. Retrieved April 24, 2009.

PC game

View on GrokipediaHistory

Origins in academic and mainframe computing

The earliest known graphical computer game, OXO, was developed in 1952 by A.S. Douglas at the University of Cambridge as part of his PhD thesis on human-computer interaction using the EDSAC stored-program computer.[6] OXO simulated tic-tac-toe (noughts and crosses) on a 3x3 grid displayed via five-hole paper tape plotting, allowing a human player to compete against an unbeatable computer opponent programmed with a minimax algorithm.[6] In 1958, physicist William Higinbotham created Tennis for Two at Brookhaven National Laboratory to entertain visitors during an open house, using a Donner Model 30 analog computer connected to a five-inch oscilloscope for display.[7] The game depicted a side-view tennis match where players adjusted ball angle and energy via analog controllers, with the trajectory influenced by simulated gravity and an optional mountain backdrop; it was dismantled after the event and never patented or preserved in its original form.[7] A pivotal advancement occurred in 1962 when MIT students, led by Steve Russell, programmed Spacewar! on the PDP-1 minicomputer acquired by the university.[8] This two-player space combat game featured vector graphics on a CRT display, including spaceship controls, photon torpedoes, and a central star with gravitational pull, controlled via custom switch boxes.[8] Spacewar! spread rapidly among academic institutions through shared source code and demonstrations, influencing subsequent game development by showcasing real-time interaction and competitive multiplayer elements on digital hardware.[8] Throughout the 1960s and into the 1970s, university mainframes hosted numerous student-created games, often text-based or simple graphical simulations, fostering a hacker culture of recreational programming that laid the groundwork for personal computing entertainment.[9]Emergence on personal computers (1970s–1980s)

The introduction of affordable personal computers in the mid-1970s laid the groundwork for dedicated gaming software, transitioning from mainframe experiments to home use. The Apple II, released in June 1977 by Apple Computer, featured color graphics and sound capabilities that distinguished it from earlier text-only systems like the 1975 Altair 8800, enabling the creation of visually engaging games.[10] Early titles included ports of text adventures such as Colossal Cave Adventure, but the platform's expandability via peripherals like disk drives fostered a burgeoning software market. By 1980, over 200 games had been released for the Apple II, establishing it as the dominant gaming platform of the era.[11] Pioneering developers emerged to exploit these hardware advances. In 1980, Ken and Roberta Williams founded On-Line Systems (later renamed Sierra On-Line in 1982) and released Mystery House, the first adventure game to incorporate static graphics alongside text parsers, drawing inspiration from Agatha Christie's And Then There Were None.[12] [13] Simultaneously, Infocom commercialized text-based interactive fiction with Zork I: The Great Underground Empire in December 1980, initially for platforms including the Apple II and TRS-80, emphasizing narrative depth over visuals through sophisticated parsing.[14] These innovations defined genres: graphical adventures from Sierra and parser-driven fiction from Infocom, with sales reflecting demand—Zork titles moved tens of thousands of copies annually by the mid-1980s. Role-playing games also took root, with Wizardry: Proving Grounds of the Mad Overlord launching in 1981 for the Apple II, introducing first-person dungeon crawling and party-based mechanics that influenced later titles.[15] Richard Garriott's Ultima I: The First Age of Darkness, also 1981 for Apple II, pioneered open-world elements in computer RPGs.[16] The IBM Personal Computer's debut in August 1981, equipped with optional Color Graphics Adapter (CGA) supporting four colors, initially hosted text adventures like Microsoft's Adventure but soon accommodated ports and originals such as Microsoft Flight Simulator in 1982.[17] [18] Standardization via the IBM PC's open architecture spurred cloning and broader adoption, shifting focus from hobbyist coding to commercial publishing by the mid-1980s, exemplified by Sierra's King's Quest in 1984, which advanced animated graphics.[19] This period marked PC gaming's maturation, driven by hardware accessibility and genre innovation rather than arcade mimicry.Expansion and 3D revolution (1990s)

The 1990s marked significant expansion in PC gaming through hardware advancements and distribution innovations, alongside the shift to 3D graphics that transformed gameplay and visuals. CD-ROM drives, offering 650 MB storage compared to floppy disks' 1.44 MB, became widespread by the mid-decade, enabling richer content such as full-motion video and high-fidelity audio in titles like The 7th Guest (1993).[20] This transition supported genre diversification, including real-time strategy games like Dune II (1992) and Warcraft: Orcs & Humans (1994), which leveraged improved processors such as the Intel 486 and emerging Pentium chips for complex simulations.[21] Shareware distribution, popularized by id Software, further broadened access, with millions downloading episodes of games via bulletin board systems and early internet connections.[21] The 3D revolution began with pseudo-3D techniques in Wolfenstein 3D, released on May 5, 1992, which used ray-casting to render maze-like environments from a first-person perspective, establishing the first-person shooter genre.[22] This evolved with Doom on December 10, 1993, employing binary space partitioning for faster rendering of textured walls and sectors, achieving 35 frames per second on contemporary hardware and inspiring widespread modding and deathmatch multiplayer.[21] Quake, launched in shareware form on June 22, 1996, introduced true polygonal 3D models and client-server networking for online play, pushing computational demands and fostering competitive gaming communities.[23] Hardware acceleration accelerated the revolution, with 3dfx's Voodoo Graphics card debuting in November 1996, providing dedicated 3D rendering capabilities like bilinear filtering and alpha blending for smoother, more immersive visuals in games such as Quake II (1997).[24] The release of Windows 95 on August 24, 1995, streamlined software installation via plug-and-play support and laid groundwork for DirectX APIs, reducing compatibility issues and attracting developers to PC as a platform for cutting-edge titles.[25] By decade's end, these developments elevated PC gaming's technical superiority, with sales of 3D accelerators surging and genres like immersive sims (Thief: The Dark Project, 1998) exploiting spatial awareness and physics.[26]Digital distribution and online dominance (2000s)

The proliferation of broadband internet in the early 2000s fundamentally enabled the transition to digital distribution and persistent online gaming on PCs, as download speeds increased from dial-up's limitations to averages exceeding 1 Mbps by 2005 in many developed markets, supporting larger file transfers and real-time multiplayer sessions.[27] This infrastructure shift reduced latency issues that had previously confined online play to niche audiences, allowing developers to prioritize network-dependent features over standalone experiences.[28] Valve Corporation introduced Steam on September 12, 2003, initially as a client for delivering game updates and patches to combat fragmentation across PC hardware, but it rapidly expanded into a full digital storefront by offering direct purchases and downloads of titles like Half-Life 2.[29] By 2005, Steam began incorporating third-party games such as Ragdoll Kung Fu and Darwinia, diversifying beyond Valve's ecosystem and establishing a model for centralized distribution that bypassed traditional retail logistics and shelf-space constraints.[30] This platform's always-online authentication and automatic updates served as a practical response to high PC piracy rates, where unprotected software could be easily replicated and shared via peer-to-peer networks, leading publishers to favor digital sales for better revenue retention and user verification.[31] Online multiplayer emerged as the dominant paradigm, with first-person shooters like Counter-Strike (ongoing updates through the decade) fostering competitive clans and servers that drew sustained player bases via broadband-enabled matchmaking. Massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs) exemplified this trend, as Blizzard Entertainment's World of Warcraft, released November 23, 2004, integrated seamless digital updates and subscription-based online persistence, attracting global audiences through expansive virtual economies and social mechanics that required constant connectivity. Publishers increasingly bundled online components as core features, evident in franchises like Battlefield 1942 (2002) and its sequels, where large-scale battles relied on dedicated servers, diminishing the appeal of offline-only titles amid rising expectations for communal play.[32] Digital platforms like Steam consolidated dominance by the late 2000s, integrating social tools, mods, and anti-cheat systems that reinforced online ecosystems, while physical media sales declined as convenience and piracy countermeasures favored downloadable content. This era's innovations laid the groundwork for PC gaming's resilience against console competition, emphasizing software agility over hardware silos.[33]Esports, indie boom, and hardware resurgence (2010s–2020s)

The 2010s and 2020s marked a period of robust expansion for PC gaming, driven by the professionalization of esports, the democratization of game development through digital platforms, and innovations in consumer hardware that enhanced graphical fidelity and performance. PC platforms hosted many of the era's most prominent competitive titles, while accessible distribution channels like Steam enabled independent developers to achieve commercial viability without traditional publisher support. Concurrently, advancements in graphics processing units (GPUs) and related technologies reinforced PC's edge in delivering high-end experiences, contributing to sustained revenue growth that outpaced consoles in non-mobile segments.[34][35] Esports on PC platforms experienced explosive growth, with viewership rising from approximately 435.7 million in 2020 to 532.1 million in 2022, and projections exceeding 640 million by the end of 2025.[36][37] Major PC-centric tournaments, such as the League of Legends World Championship, drew peak audiences of 6.94 million in 2024, underscoring the draw of multiplayer PC games like Counter-Strike: Global Offensive, Dota 2, and Valorant.[38] The global esports market, heavily reliant on PC infrastructure for competitive play, expanded from a nascent state in the early 2010s—where events like the Cyberathlete Professional League offered over $1 million in prizes by 2005—to a projected value of $649.4 million in 2025, growing at a compound annual rate of 18% toward $2.07 billion by 2032.[39][40] This surge attracted substantial sponsorships and media coverage, transforming PC gaming into a spectator sport with dedicated audiences of 273 million enthusiasts by 2022.[41] The indie game sector flourished on PC, particularly via Valve's Steam platform, which lowered barriers to entry through features like Steam Greenlight (launched 2012) and Direct publishing tools. Indie titles captured 31% of Steam's revenue in 2023, up from 25% in 2018, and reached 48% in 2024, generating nearly $4 billion in gross revenue on the platform during the first part of that year alone.[42][43][44] This boom reflected a shift toward smaller teams producing innovative, niche experiences, with over 50% of indie games historically earning less than $4,000 but top performers driving disproportionate returns—median self-published indie revenue at $3,285 versus $16,222 for publisher-backed ones.[45][46] PC's modifiability and open ecosystem amplified indie longevity, allowing community enhancements that extended playtime and virality beyond initial releases. Hardware developments revitalized PC gaming's appeal, with GPU manufacturers NVIDIA and AMD introducing architectures supporting real-time ray tracing—a technique simulating realistic light behavior—for consumer use starting with NVIDIA's GeForce RTX 20-series in 2018.[47] AMD followed with ray tracing acceleration in its RX 6000-series (2020) and enhanced it via dedicated Radiance Cores announced in 2025 for future RDNA architectures, improving path tracing efficiency.[48][49] These innovations, alongside support for high refresh rates (up to 360Hz+ monitors) and AI-driven upscaling like DLSS (introduced 2018), enabled PCs to outperform consoles in visual quality and frame rates, fostering a resurgence in enthusiast builds.[50] By 2024, PC gaming claimed 53% of non-mobile revenue share versus 47% for consoles, reflecting hardware's role in sustaining demand amid escalating graphical demands.[35][51]Platform Distinctions and Advantages

Modifiability and community-driven enhancements

Personal computers' open hardware architecture and accessible file systems enable extensive modifiability, allowing users to alter game code, assets, textures, and mechanics far beyond what proprietary console ecosystems permit. This stems from developers often releasing tools, documentation, or even source code, facilitating community interventions such as bug fixes, performance optimizations, and content expansions that official updates may overlook.[52][53] Modding originated in the 1980s with simple alterations, like Silas Warner's 1981 modification to Castle Wolfenstein that replaced enemy sprites with aliens, but gained momentum in the 1990s through id Software's design choices. Doom (1993) featured a WAD file format that permitted easy level and sprite replacements, spawning thousands of user-created maps and variants shortly after release. Quake (1996) further advanced this by providing SDKs and later open-sourcing its engine, enabling total conversions that reshaped gameplay fundamentals.[54][52] Community-driven enhancements have profoundly extended game longevity and spurred industry innovation, with mods often addressing technical shortcomings or introducing unmet player demands. For instance, Counter-Strike (1999), a mod for Half-Life (1998), refined tactical shooting mechanics and amassed millions of players, leading Valve to acquire and commercialize it as a standalone title in 2000. Similarly, Defense of the Ancients (2003), a Warcraft III mod, pioneered multiplayer online battle arena gameplay, directly influencing Dota 2 (2013) and titles like League of Legends (2009). DayZ (2012), modded from Arma 2 (2009), popularized survival horror in open worlds, inspiring its 2018 standalone version and the battle royale genre via derivatives like PlayerUnknown's Battlegrounds (2017). These cases illustrate how PC modding transforms niche experiments into commercial successes, unfeasible on locked console platforms.[55][56][57] Modern platforms amplify these capabilities: Steam Workshop, integrated since 2011, streamlines mod subscriptions and updates for games like Skyrim and Cities: Skylines, hosting millions of items with automated compatibility checks. Nexus Mods, a dedicated repository since 2001, reported 10 billion total downloads by February 2024 across 539,682 files for over 4,000 games, with Skyrim Special Edition (2016) alone supporting 119,000 mods that overhaul quests, graphics, and physics. Such ecosystems enable graphical overhauls—like high-resolution texture packs for The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim (2011)—and unofficial patches fixing persistent bugs, sustaining titles for decades post-release.[58][59][60] This modifiability fosters causal feedback loops where player innovations inform developer practices, as seen in engine designs prioritizing extensibility (e.g., Source engine's mod-friendliness yielding Team Fortress from Quake). Unlike consoles, where modifications require jailbreaking and risk bans, PC openness minimizes barriers, yielding empirical benefits in replayability and cost-efficiency—users access free enhancements rather than paid DLC equivalents. However, it demands technical literacy, and poorly vetted mods can introduce malware, underscoring the need for reputable distribution sites.[52][53][61]Digital storefronts and distribution models

The transition from physical media to digital distribution in PC gaming accelerated in the early 2000s, driven by broadband adoption and the need for efficient patching amid complex software updates.[62] Valve's Steam platform, launched on September 12, 2003, initially as a tool for distributing updates to its own titles like Half-Life and Counter-Strike, pioneered centralized digital storefronts by automating downloads and combating cheating through integrated verification.[33] By opening to third-party developers, Steam evolved into the dominant PC distribution hub, capturing 74-75% of the digital market share as of 2025 through features like automatic updates, community integration, and frequent sales.[63] Competing storefronts emerged to challenge Steam's hegemony, often emphasizing niches like exclusivity or user freedoms. Epic Games Store, debuting in December 2018, secured roughly 3% market share by 2025 via aggressive tactics including timed exclusives, an 88/12 revenue split favoring developers (versus Steam's 70/30), and weekly free game giveaways to build its library.[63] GOG.com, established in 2008 by CD Projekt, differentiates with a DRM-free model allowing offline play and true ownership transfers, appealing to preservationists despite smaller scale; it contributes to the collective 70%+ share held by Steam, Epic, and GOG in PC sales.[64] Niche platforms like itch.io cater to indie developers with flexible pricing and no upfront fees, while Humble Bundle focuses on charitable bundles, and Microsoft's Xbox app integrates PC with console ecosystems.[65] Distribution models vary, with outright purchases granting revocable licenses rather than perpetual ownership, as end-user agreements typically permit usage under platform terms that can be altered or terminated—exemplified by delistings or account bans removing access without refunds.[66] Free-to-play (F2P) dominates multiplayer titles like Fortnite and League of Legends, monetizing via in-game purchases for cosmetics or progression while keeping entry barriers low to maximize user acquisition.[67] Subscription services, such as Xbox Game Pass for PC launched in 2019, provide access to rotating libraries for a monthly fee, amassing over 25 million subscribers by 2023 but raising concerns over reduced upfront developer revenues and potential title rotations disrupting long-term engagement.[68] These models enable instant global reach and algorithmic recommendations but expose gamers to platform dependencies, where control resides with distributors enforcing digital rights management (DRM) to prevent unauthorized sharing, though DRM-free options like GOG mitigate such restrictions at the cost of broader piracy risks.[69]Upgradability, longevity, and backward compatibility

Personal computers used for gaming feature modular architectures that facilitate component-level upgrades, such as replacing graphics processing units (GPUs), central processing units (CPUs), and random-access memory (RAM), without necessitating a complete system overhaul.[70] This upgradability allows users to incrementally improve performance to meet rising graphical and computational demands of new titles, often extending hardware utility across multiple software generations.[71] For instance, GPU upgrades alone can transform frame rates from sub-30 fps to over 60 fps in demanding games, preserving investment in other components like motherboards and storage.[71] Such flexibility contributes to superior longevity relative to fixed-hardware consoles. Well-maintained gaming PCs, with periodic upgrades every 2-3 years for key parts like GPUs, can sustain high-performance gaming for 5-10 years or longer, outpacing console cycles of 7-8 years where no internal enhancements are possible.[72][73] Statistics indicate console generations enforce predictable but inflexible upgrade schedules, while PCs enable cost-effective extensions, with full system replacements occurring less frequently—typically every 8-10 years for avid gamers.[74][73] Backward compatibility in PC gaming benefits from layered software ecosystems, particularly Microsoft's Windows, which preserves API continuity through DirectX evolutions and built-in compatibility modes supporting applications from Windows 95 onward.[75] The Program Compatibility Troubleshooter, introduced in Windows XP and refined in subsequent versions up to Windows 11, emulates older environments to resolve issues like resolution mismatches or driver conflicts in legacy games.[75] This enables execution of titles from the 1990s on contemporary hardware, supplemented by community-developed wrappers like DxWnd for DirectX adaptations or Proton for cross-platform Linux compatibility. Unlike consoles, which often require emulation layers prone to licensing hurdles, PCs inherently support binary execution of x86 software, fostering preservation without proprietary restrictions.[76]Superior performance potential versus consoles

Personal computers offer superior performance potential compared to consoles primarily due to their modular architecture, which enables users to integrate cutting-edge components far exceeding the fixed hardware specifications of console systems.[77] For instance, while the PlayStation 5 and Xbox Series X, released in 2020, feature custom AMD GPUs delivering approximately 10-12 teraflops of compute performance, high-end PCs in 2025 can incorporate graphics cards such as the NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090, which exceeds 80 teraflops in raw FP32 performance, allowing for substantially higher graphical fidelity and computational demands.[78] This disparity arises from PCs' ability to leverage annual hardware advancements, including overclocking and multi-GPU configurations, unfeasible on locked-down consoles. In terms of frame rates and resolutions, PCs routinely achieve outputs unattainable on consoles without developer compromises. High-end configurations support uncapped frame rates exceeding 240 fps at 4K resolution in optimized titles, paired with high-refresh-rate monitors (e.g., 360Hz displays), whereas consoles are typically limited to 120 fps caps even in performance modes, often at reduced resolutions or graphical settings to maintain stability.[78] Benchmarks in games like Cyberpunk 2077 demonstrate PCs rendering full ray tracing and path tracing at 144 fps or higher with upscaling technologies like DLSS 3.5, while console versions on PS5 Pro (enhanced in 2024) target 60 fps with partial ray tracing and dynamic resolution scaling below native 4K.[79] This potential stems from PCs' access to proprietary features like NVIDIA's frame generation and AMD's Fluid Motion Frames, which consoles approximate but cannot fully replicate due to hardware constraints.[80] Moreover, PC upgradability ensures sustained superiority over console generations, which last 6-8 years before obsolescence. A user can incrementally upgrade a PC's CPU, GPU, RAM, and storage to match or exceed next-generation consoles projected for 2028, such as rumored PS6 systems with enhanced but still fixed AMD APUs, without replacing the entire platform.[81] Empirical data from cross-platform titles shows PCs maintaining peak performance longer; for example, in Monster Hunter Wilds (2025), maxed 4K settings on PC yield sharper textures and draw distances than console versions locked to 30-60 fps modes.[82] While consoles benefit from unified optimization—reducing variability—PCs' raw potential enables emergent capabilities like AI-driven upscaling and modded enhancements that push beyond developer-intended limits.[83]Technical Foundations

Hardware evolution and components