Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Morphism

View on WikipediaIn mathematics, a morphism is a concept of category theory that generalizes structure-preserving maps such as homomorphism between algebraic structures, functions from a set to another set, and continuous functions between topological spaces. Although many examples of morphisms are structure-preserving maps, morphisms need not be maps, but they can be composed in a way that is similar to function composition.

Morphisms and objects are constituents of a category. Morphisms, also called maps or arrows, relate two objects called the source and the target of the morphism. There is a partial operation, called composition, on the morphisms of a category that is defined if the target of the first morphism equals the source of the second morphism. The composition of morphisms behaves like function composition (associativity of composition when it is defined, and existence of an identity morphism for every object).

Morphisms and categories recur in much of contemporary mathematics. Originally, they were introduced for homological algebra and algebraic topology. They belong to the foundational tools of Grothendieck's scheme theory, a generalization of algebraic geometry that applies also to algebraic number theory.

Definition

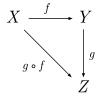

[edit]A category C consists of two classes, one of objects and the other of morphisms. There are two objects that are associated to every morphism, the source and the target. A morphism f from X to Y is a morphism with source X and target Y; it is commonly written as f : X → Y or X Y the latter form being better suited for commutative diagrams.

For many common categories, an object is a set (often with some additional structure) and a morphism is a function from an object to another object. Therefore, the source and the target of a morphism are often called domain and codomain respectively.

Morphisms are equipped with a partial binary operation, called composition (partial because the composition is not necessarily defined over every pair of morphisms of a category). The composition of two morphisms f and g is defined precisely when the target of f is the source of g, and is denoted g ∘ f (or sometimes simply gf). The source of g ∘ f is the source of f, and the target of g ∘ f is the target of g. The composition satisfies two axioms:

- Identity

- For every object X, there exists a morphism idX : X → X called the identity morphism on X, such that for every morphism f : A → B we have idB ∘ f = f = f ∘ idA.

- Associativity

- h ∘ (g ∘ f) = (h ∘ g) ∘ f whenever all the compositions are defined, i.e. when the target of f is the source of g, and the target of g is the source of h.

For a concrete category (a category in which the objects are sets, possibly with additional structure, and the morphisms are structure-preserving functions), the identity morphism is just the identity function, and composition is just ordinary composition of functions.

The composition of morphisms is often represented by a commutative diagram. For example,

The collection of all morphisms from X to Y is denoted HomC(X, Y) or simply Hom(X, Y) and called the hom-set between X and Y. Some authors write MorC(X, Y), Mor(X, Y) or C(X, Y). The term hom-set is something of a misnomer, as the collection of morphisms is not required to be a set; a category where Hom(X, Y) is a set for all objects X and Y is called locally small. Because hom-sets may not be sets, some people prefer to use the term "hom-class".

The domain and codomain are in fact part of the information determining a morphism. For example, in the category of sets, where morphisms are functions, two functions may be identical as sets of ordered pairs, while having different codomains. The two functions are distinct from the viewpoint of category theory. Many authors require that the hom-classes Hom(X, Y) be disjoint. In practice, this is not a problem because if this disjointness does not hold, it can be assured by appending the domain and codomain to the morphisms (say, as the second and third components of an ordered triple).

Some special morphisms

[edit]Monomorphisms and epimorphisms

[edit]A morphism f : X → Y is called a monomorphism if f ∘ g1 = f ∘ g2 implies g1 = g2 for all morphisms g1, g2 : Z → X. A monomorphism can be called a mono for short, and we can use monic as an adjective.[1] A morphism f has a left inverse or is a split monomorphism if there is a morphism g : Y → X such that g ∘ f = idX. Thus f ∘ g : Y → Y is idempotent; that is, (f ∘ g)2 = f ∘ (g ∘ f) ∘ g = f ∘ g. The left inverse g is also called a retraction of f.[1]

Morphisms with left inverses are always monomorphisms (f-1l ∘ f ∘ g1 = f-1l ∘ f ∘ g2 implies g1 = g2, where f-1l is the left inverse of f), but the converse is not true in general; a monomorphism may fail to have a left inverse. In concrete categories, where morphisms are functions, a morphism that has a left inverse is injective, and a morphism that is injective is a monomorphism. In concrete categories, monomorphisms are often, but not always, injective; thus the condition of being an injection is stronger than that of being a monomorphism, but weaker than that of being a split monomorphism.

Dually to monomorphisms, a morphism f : X → Y is called an epimorphism if g1 ∘ f = g2 ∘ f implies g1 = g2 for all morphisms g1, g2 : Y → Z. An epimorphism can be called an epi for short, and we can use epic as an adjective.[1] A morphism f has a right inverse or is a split epimorphism if there is a morphism g : Y → X such that f ∘ g = idY. The right inverse g is also called a section of f.[1] Morphisms having a right inverse are always epimorphisms (g1 ∘ f ∘ f-1r = g2 ∘ f ∘ f-1r implies g1 = g2 where f-1r is the right inverse of f), but the converse is not true in general, as an epimorphism may fail to have a right inverse.

If a monomorphism f splits with left inverse g, then g is a split epimorphism with right inverse f. In concrete categories, a function that has a right inverse is surjective.[2] Thus, in concrete categories, epimorphisms are often, but not always, surjective. The condition of being a surjection is stronger than that of being an epimorphism, but weaker than that of being a split epimorphism. In the category of sets, the statement that every surjection has a section is equivalent to the axiom of choice.

A morphism that is both an epimorphism and a monomorphism is called a bimorphism.

For example, in the category of vector spaces over a fixed field, injective morphisms, monomorphisms and split homomorphisms are the same, as well as surjective morphisms, epimorphisms and split epimorphisms.

In the category of commutative rings, monomorphisms and injective morphisms are the same, while the injection from into is an epimorphism that is not surjective; it is neither a split epimorphism nor a split monomorphism. (See Homomorphism#Special homomorphisms for more details and proofs.)

Isomorphisms

[edit]A morphism f : X → Y is called an isomorphism if there exists a morphism g : Y → X such that f ∘ g = idY and g ∘ f = idX. If a morphism has both left-inverse and right-inverse, then the two inverses are equal, so f is an isomorphism, and g is called simply the inverse of f. Inverse morphisms, if they exist, are unique. The inverse g is also an isomorphism, with inverse f. Two objects with an isomorphism between them are said to be isomorphic or equivalent.

While every isomorphism is a bimorphism, a bimorphism is not necessarily an isomorphism. For example, in the category of commutative rings the inclusion Z → Q is a bimorphism that is not an isomorphism. However, any morphism that is both an epimorphism and a split monomorphism, or both a monomorphism and a split epimorphism, must be an isomorphism. A category, such as a Set, in which every bimorphism is an isomorphism is known as a balanced category.

Endomorphisms and automorphisms

[edit]A morphism f : X → X (that is, a morphism with identical source and target) is an endomorphism of X. A split endomorphism is an idempotent endomorphism f if f admits a decomposition f = h ∘ g with g ∘ h = id. In particular, the Karoubi envelope of a category splits every idempotent morphism.

An automorphism is a morphism that is both an endomorphism and an isomorphism. In every category, the automorphisms of an object always form a group, called the automorphism group of the object.

Examples

[edit]- For algebraic structures commonly considered in algebra, such as groups, rings, modules, etc., the morphisms are usually the homomorphisms, and the notions of isomorphism, automorphism, endomorphism, epimorphism, and monomorphism are the same as the above defined ones. However, in the case of rings, "epimorphism" is often considered as a synonym of "surjection", although there are ring epimorphisms that are not surjective (e.g., when embedding the integers in the rational numbers).

- In the category of topological spaces, the morphisms are the continuous functions and isomorphisms are called homeomorphisms. There are continuous bijections (that is, isomorphisms of sets) that are not homeomorphisms.

- In the category of smooth manifolds, the morphisms are the smooth functions and isomorphisms are called diffeomorphisms.

- In the category of small categories, the morphisms are functors.

- In a functor category, the morphisms are natural transformations.

For more examples, see Category theory.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- Jacobson, Nathan (2009), Basic algebra, vol. 2 (2nd ed.), Dover, ISBN 978-0-486-47187-7.

- Adámek, Jiří; Herrlich, Horst; Strecker, George E. (1990). Abstract and Concrete Categories (PDF). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-60922-6. Now available as free on-line edition (4.2MB PDF).

External links

[edit]- "Morphism", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

Morphism

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

In category theory, a morphism is an arrow connecting two objects in a category, typically denoted as , where and are objects, indicating that maps from to .[5] Morphisms are required to respect the underlying structure of the category; for instance, in concrete categories like the category of sets, they correspond to functions that preserve the specified relations or operations between objects, with each morphism having a well-defined domain (the source object) and codomain (the target object).[5] The term "morphism" was introduced by Samuel Eilenberg and Saunders Mac Lane in 1945 to describe these arrows within the framework of category theory.[2] A simple morphism can be illustrated diagrammatically as follows:A ──f──> B

A ──f──> B