Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Universal property

View on Wikipedia

In mathematics, more specifically in category theory, a universal property is a property that characterizes up to an isomorphism the result of some constructions. Thus, universal properties can be used for defining some objects independently from the method chosen for constructing them. For example, the definitions of the integers from the natural numbers, of the rational numbers from the integers, of the real numbers from the rational numbers, and of polynomial rings from the field of their coefficients can all be done in terms of universal properties. In particular, the concept of universal property allows a simple proof that all constructions of real numbers are equivalent: it suffices to prove that they satisfy the same universal property.

Technically, a universal property is defined in terms of categories and functors by means of a universal morphism (see § Formal definition, below). Universal morphisms can also be thought more abstractly as initial or terminal objects of a comma category (see § Connection with comma categories, below).

Universal properties occur almost everywhere in mathematics, and the use of the concept allows the use of general properties of universal properties for easily proving some properties that would need boring verifications otherwise. For example, given a commutative ring R, the field of fractions of the quotient ring of R by a prime ideal p can be identified with the residue field of the localization of R at p; that is (all these constructions can be defined by universal properties).

Other objects that can be defined by universal properties include: all free objects, direct products and direct sums, free groups, free lattices, Grothendieck group, completion of a metric space, completion of a ring, Dedekind–MacNeille completion, product topologies, Stone–Čech compactification, tensor products, inverse limit and direct limit, kernels and cokernels, quotient groups, quotient vector spaces, and other quotient spaces.

Motivation

[edit]Before giving a formal definition of universal properties, we offer some motivation for studying such constructions.

- The concrete details of a given construction may be messy, but if the construction satisfies a universal property, one can forget all those details: all there is to know about the construction is already contained in the universal property. Proofs often become short and elegant if the universal property is used rather than the concrete details. For example, the tensor algebra of a vector space is slightly complicated to construct, but much easier to deal with by its universal property.

- Universal properties define objects uniquely up to a unique isomorphism.[1] Therefore, one strategy to prove that two objects are isomorphic is to show that they satisfy the same universal property.

- Universal constructions are functorial in nature: if one can carry out the construction for every object in a category C then one obtains a functor on C. Furthermore, this functor is a right or left adjoint to the functor U used in the definition of the universal property.[2]

- Universal properties occur everywhere in mathematics. By understanding their abstract properties, one obtains information about all these constructions and can avoid repeating the same analysis for each individual instance.

Formal definition

[edit]To understand the definition of a universal construction, it is important to look at examples. Universal constructions were not defined out of thin air, but were rather defined after mathematicians began noticing a pattern in many mathematical constructions (see Examples below). Hence, the definition may not make sense to one at first, but will become clear when one reconciles it with concrete examples.

Let be a functor between categories and . In what follows, let be an object of , and be objects of , and be a morphism in .

Then, the functor maps , and in to , and in .

A universal morphism from to is a unique pair in which has the following property, commonly referred to as a universal property:

For any morphism of the form in , there exists a unique morphism in such that the following diagram commutes:

We can dualize this categorical concept. A universal morphism from to is a unique pair that satisfies the following universal property:

For any morphism of the form in , there exists a unique morphism in such that the following diagram commutes:

Note that in each definition, the arrows are reversed. Both definitions are necessary to describe universal constructions which appear in mathematics; but they also arise due to the inherent duality present in category theory. In either case, we say that the pair which behaves as above satisfies a universal property.

Connection with comma categories

[edit]Universal morphisms can be described more concisely as initial and terminal objects in a comma category (i.e. one where morphisms are seen as objects in their own right).

Let be a functor and an object of . Then recall that the comma category is the category where

- Objects are pairs of the form , where is an object in

- A morphism from to is given by a morphism in such that the diagram commutes:

Now suppose that the object in is initial. Then for every object , there exists a unique morphism such that the following diagram commutes.

Note that the equality here simply means the diagrams are the same. Also note that the diagram on the right side of the equality is the exact same as the one offered in defining a universal morphism from to . Therefore, we see that a universal morphism from to is equivalent to an initial object in the comma category .

Conversely, recall that the comma category is the category where

- Objects are pairs of the form where is an object in

- A morphism from to is given by a morphism in such that the diagram commutes:

Suppose is a terminal object in . Then for every object , there exists a unique morphism such that the following diagrams commute.

The diagram on the right side of the equality is the same diagram pictured when defining a universal morphism from to . Hence, a universal morphism from to corresponds with a terminal object in the comma category .

Examples

[edit]Below are a few examples, to highlight the general idea. The reader can construct numerous other examples by consulting the articles mentioned in the introduction.

Tensor algebras

[edit]Let be the category of vector spaces -Vect over a field and let be the category of algebras -Alg over (assumed to be unital and associative). Let be the forgetful functor which assigns to each algebra its underlying vector space.

Given any vector space over we can construct the tensor algebra . The tensor algebra is characterized by the fact:

- “Any linear map from to an algebra can be uniquely extended to an algebra homomorphism from to .”

This statement is an initial property of the tensor algebra since it expresses the fact that the pair , where is the inclusion map, is a universal morphism from the vector space to the functor .

Since this construction works for any vector space , we conclude that is a functor from -Vect to -Alg. This means that is left adjoint to the forgetful functor (see the section below on relation to adjoint functors).

Products

[edit]A categorical product can be characterized by a universal construction. For concreteness, one may consider the Cartesian product in Set, the direct product in Grp, or the product topology in Top, where products exist.

Let and be objects of a category with finite products. The product of and is an object × together with two morphisms

- :

- :

such that for any other object of and morphisms and there exists a unique morphism such that and .

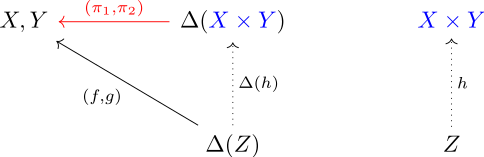

To understand this characterization as a universal property, take the category to be the product category and define the diagonal functor

by and . Then is a universal morphism from to the object of : if is any morphism from to , then it must equal a morphism from to followed by . As a commutative diagram:

For the example of the Cartesian product in Set, the morphism comprises the two projections and . Given any set and functions the unique map such that the required diagram commutes is given by .[3]

Limits and colimits

[edit]Categorical products are a particular kind of limit in category theory. One can generalize the above example to arbitrary limits and colimits.

Let and be categories with a small index category and let be the corresponding functor category. The diagonal functor

is the functor that maps each object in to the constant functor (i.e. for each in and for each in ) and each morphism in to the natural transformation in defined as, for every object of , the component at . In other words, the natural transformation is the one defined by having constant component for every object of .

Given a functor (thought of as an object in ), the limit of , if it exists, is nothing but a universal morphism from to . Dually, the colimit of is a universal morphism from to .

Properties

[edit]Existence and uniqueness

[edit]Defining a quantity does not guarantee its existence. Given a functor and an object of , there may or may not exist a universal morphism from to . If, however, a universal morphism does exist, then it is essentially unique. Specifically, it is unique up to a unique isomorphism: if is another pair, then there exists a unique isomorphism such that . This is easily seen by substituting in the definition of a universal morphism.

It is the pair which is essentially unique in this fashion. The object itself is only unique up to isomorphism. Indeed, if is a universal morphism and is any isomorphism then the pair , where is also a universal morphism.

Equivalent formulations

[edit]The definition of a universal morphism can be rephrased in a variety of ways. Let be a functor and let be an object of . Then the following statements are equivalent:

- is a universal morphism from to

- is an initial object of the comma category

- is a representation of , where its components are defined by

for each object in

The dual statements are also equivalent:

- is a universal morphism from to

- is a terminal object of the comma category

- is a representation of , where its components are defined by

for each object in

Relation to adjoint functors

[edit]Suppose is a universal morphism from to and is a universal morphism from to . By the universal property of universal morphisms, given any morphism there exists a unique morphism such that the following diagram commutes:

If every object of admits a universal morphism to , then the assignment and defines a functor . The maps then define a natural transformation from (the identity functor on ) to . The functors are then a pair of adjoint functors, with left-adjoint to and right-adjoint to .

Similar statements apply to the dual situation of terminal morphisms from . If such morphisms exist for every in one obtains a functor which is right-adjoint to (so is left-adjoint to ).

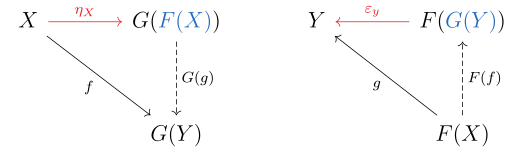

Indeed, all pairs of adjoint functors arise from universal constructions in this manner. Let and be a pair of adjoint functors with unit and co-unit (see the article on adjoint functors for the definitions). Then we have a universal morphism for each object in and :

- For each object in , is a universal morphism from to . That is, for all there exists a unique for which the following diagrams commute.

- For each object in , is a universal morphism from to . That is, for all there exists a unique for which the following diagrams commute.

Universal constructions are more general than adjoint functor pairs: a universal construction is like an optimization problem; it gives rise to an adjoint pair if and only if this problem has a solution for every object of (equivalently, every object of ).

History

[edit]Universal properties of various topological constructions were presented by Pierre Samuel in 1948. They were later used extensively by Bourbaki. The closely related concept of adjoint functors was introduced independently by Daniel Kan in 1958.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Jacobson (2009), Proposition 1.6, p. 44.

- ^ See for example, Polcino & Sehgal (2002), p. 133. exercise 1, about the universal property of group rings.

- ^ Fong, Brendan; Spivak, David I. (2018-10-12). "Seven Sketches in Compositionality: An Invitation to Applied Category Theory". arXiv:1803.05316 [math.CT].

References

[edit]- Paul Cohn, Universal Algebra (1981), D.Reidel Publishing, Holland. ISBN 90-277-1213-1.

- Mac Lane, Saunders (1998). Categories for the Working Mathematician. Graduate Texts in Mathematics 5 (2nd ed.). Springer. ISBN 0-387-98403-8.

- Borceux, F. Handbook of Categorical Algebra: vol 1 Basic category theory (1994) Cambridge University Press, (Encyclopedia of Mathematics and its Applications) ISBN 0-521-44178-1

- N. Bourbaki, Livre II : Algèbre (1970), Hermann, ISBN 0-201-00639-1.

- Milies, César Polcino; Sehgal, Sudarshan K.. An introduction to group rings. Algebras and applications, Volume 1. Springer, 2002. ISBN 978-1-4020-0238-0

- Jacobson. Basic Algebra II. Dover. 2009. ISBN 0-486-47187-X

- Roman, Steven (2017). "Universality". An Introduction to the Language of Category Theory. Compact Textbooks in Mathematics. pp. 71–86. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-41917-6_3. ISBN 978-3-319-41916-9.

- Abramsky, S.; Tzevelekos, N. (2010). "Introduction to Categories and Categorical Logic". New Structures for Physics. Lecture Notes in Physics. Vol. 813. pp. 3–94. arXiv:1102.1313. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-12821-9_1. ISBN 978-3-642-12820-2.

- Leinster, Tom (2014). Basic Category Theory. arXiv:1612.09375. doi:10.1017/CBO9781107360068. ISBN 978-1-107-04424-1.

External links

[edit]- nLab, a wiki project on mathematics, physics and philosophy with emphasis on the n-categorical point of view

- André Joyal, CatLab, a wiki project dedicated to the exposition of categorical mathematics

- Hillman, Chris (2001). A Categorical Primer. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.24.3264: formal introduction to category theory.

- J. Adamek, H. Herrlich, G. Stecker, Abstract and Concrete Categories-The Joy of Cats

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: "Category Theory"—by Jean-Pierre Marquis. Extensive bibliography.

- List of academic conferences on category theory

- Baez, John, 1996,"The Tale of n-categories." An informal introduction to higher order categories.

- WildCats is a category theory package for Mathematica. Manipulation and visualization of objects, morphisms, categories, functors, natural transformations, universal properties.

- The catsters, a YouTube channel about category theory.

- Video archive of recorded talks relevant to categories, logic and the foundations of physics.

- Interactive Web page which generates examples of categorical constructions in the category of finite sets.