Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Bindle

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2007) |

A bindle is the bag, sack, or carrying device stereotypically used by the American sub-culture of hobos.[1] The bindle is colloquially known as the blanket stick, particularly within the Northeastern hobo community. They are also heavily associated with the Great Depression.

A hobo who carried a bindle was known as a bindlestiff. According to James Blish in his novel A Life for the Stars, a bindlestiff was specifically a hobo who had stolen another hobo's bindle, from the colloquialism stiff, as in steal.[citation needed]

In modern popular culture the bindle is portrayed as a stick with cloth or a blanket tied around one end for carrying items, with the entire array being carried over the shoulder. This transferred force to the shoulder, which allowed a longer-lasting and comfortable grip, especially with larger heavier loads. Particularly in cartoons, the bindles' sacks usually have a polka-dot or bandanna design. However, in actual use the bindle can take many forms.

One example of the stick-type bindle can be seen in the illustration entitled The Runaway created by Norman Rockwell for the cover of the September 20, 1958, edition of The Saturday Evening Post.[2]

Though bindles are virtually gone, they are still widely seen in popular culture as a prevalent anachronism.

The term bindle may be an alteration of the term "bundle" or similarly descend from the German word Bündel, meaning something wrapped up in a blanket and bound by cord for carrying (cf. originally Middle Dutch bundel), or have arisen as a portmanteau of bind and spindle.[3] It may also be from the Scottish dialectal bindle "cord or rope to bind things".[4]

Bindle is also a term used in forensics. It is the name for a piece of paper folded into an envelope or packet to hold trace evidence: hairs, fibers or powders.[5] Similarly, bindle is sometimes used to describe a small package of powdered drugs.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "bindle". Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 28 June 2024.

- ^ "The Runaway (1958) by Norman Rockwell". Artchive. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ "Bindle Definition & Meaning". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ "Bindle Etymology". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved July 21, 2023.

- ^ Evidence Packaging: A How-To Guide (PDF), California Department of Justice Bureau of Forensic Services, p. 32, retrieved May 30, 2023

External links

[edit]- "Folding a Paper Bindle", 2017, National Forensic Technology Training Center.

- "Paper Evidence Fold", 2014, VDFS, Virginia.

Bindle

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Etymology

Definition

A bindle is a portable bundle containing bedding, clothing, and personal possessions, typically assembled by wrapping items in a cloth or blanket and securing them with ties or knots for carrying.[5][1] It is most closely associated with itinerant laborers, transients, and members of the hobo subculture in the United States, who used it as a lightweight, makeshift container during travel on foot or by freight train.[6] The bindle is often depicted slung over the shoulder on the end of a wooden stick, allowing the carrier to distribute weight evenly while maintaining mobility over long distances.[5] This carrying method emphasized practicality and minimalism, enabling users to transport essentials without the bulk of modern luggage, and it became a hallmark of self-reliant vagabond life in rural and industrial America from the late 19th century onward.[1] Unlike fixed containers such as backpacks, the bindle's design relied on readily available materials like scraps of fabric and cordage, reflecting the resourcefulness required in transient lifestyles marked by economic hardship and migration for work.[6]Etymological Origins

The term bindle, denoting the bundled possessions carried by itinerant laborers or hobos, is of uncertain etymological origin, with earliest documented uses appearing in American English around 1897.[5] The Oxford English Dictionary records its first evidence in 1900, in writings by Josiah Flynt Willard, an early chronicler of tramp culture, suggesting it emerged in the vernacular of transient workers in the late 19th century.[7] One prevailing theory posits bindle as a phonetic variant or corruption of bundle, reflecting the object's nature as a tied or wrapped package of goods, potentially influenced by the Proto-Indo-European root bhendh- ("to bind"), which underlies English words like bind and bundle.[2] This aligns with related terms such as bindlestiff (a hobo carrying a bindle), where stiff denotes a transient worker, and the compound may trace to German dialectal bindel or Middle High German bündel, both meaning a bound bundle from the verb binden ("to bind").[8] Scottish English bindle, referring to a cord for binding items, provides another plausible antecedent, evoking the practical tying mechanism of the hobo's sack.[2] Alternative derivations include Old English bindele ("a binding or tying"), directly from bindan ("to bind"), though this lacks direct attestation in modern tramp slang contexts.[9] Speculation linking it to Yiddish has been proposed informally but lacks substantive linguistic evidence, as no clear Yiddish cognate matches the term's form or usage in American hobo subculture.[10] Overall, the word's development reflects the adaptive slang of migratory workers during industrialization, prioritizing functional descriptiveness over formal linguistic evolution, with no single origin definitively proven despite these interconnected binding motifs.[7]Historical Context

19th-Century Origins

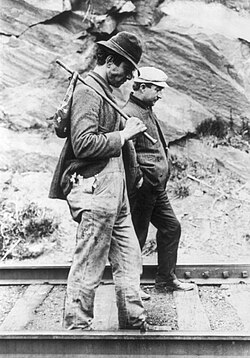

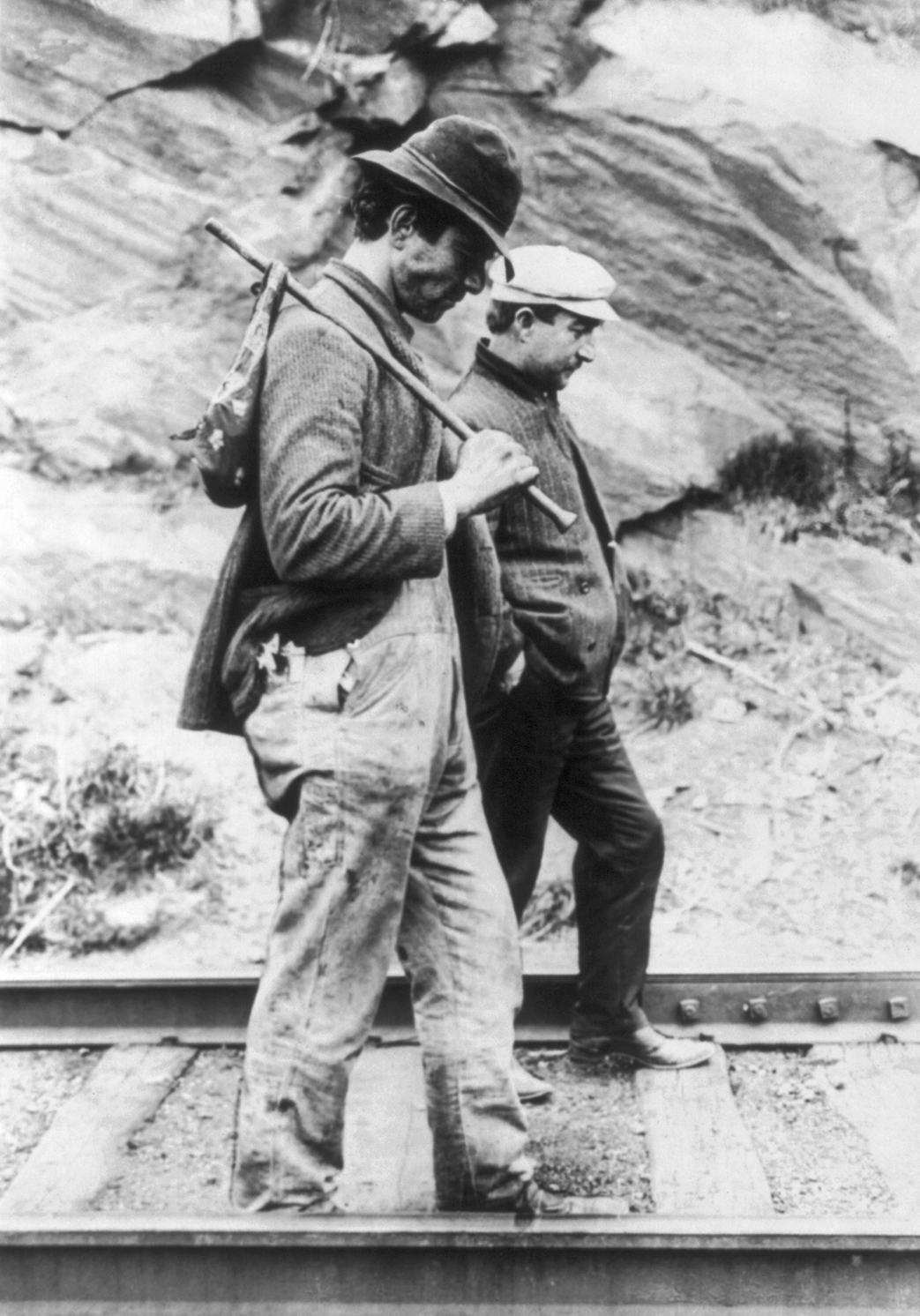

The bindle emerged as a rudimentary carrying device among itinerant workers in the United States during the post-Civil War era, particularly in the 1870s and 1880s, as the transcontinental railroad's completion in 1869 spurred mass migration for seasonal labor in mining, logging, and harvest work. Former Union and Confederate soldiers, numbering in the hundreds of thousands, often turned to transient lifestyles after demobilization, riding freight trains eastward and westward while bundling essentials like clothing, blankets, and tools in cloth to enable swift, unencumbered travel across vast distances. This method prioritized portability and balance, with the stick serving as an improvised shoulder yoke to distribute weight evenly during long treks or hops on moving railcars, predating widespread access to manufactured bags or packs.[11][12] The practice drew from practical necessities of the expanding American frontier economy, where an estimated tens of thousands of "floaters" or casual laborers traversed the West annually by the 1880s, filling labor shortages in remote areas without fixed settlements. Unlike European peddlers' packs, which often involved carts or baskets, the American bindle emphasized minimalism for rail-riding evasion of authorities and quick assembly from scavenged materials like bandanas or feed sacks. Historical accounts from the period document such bundles in use among "bindle-stiffs"—a term for these workers—highlighting their role in sustaining mobility amid economic volatility, including the Long Depression of 1873–1879, which displaced further rural populations into vagrancy.[13] The word "bindle" itself entered recorded English lexicon by 1897, derived as a phonetic alteration of "bundle" to denote the tied parcel of goods, possibly influenced by dialectal terms for binding cords. This linguistic crystallization coincided with the formalization of hobo subculture in the late 1890s, as transient populations grew to support railroad maintenance crews and migratory farmhands, with the device symbolizing self-reliant adaptation to industrial transience rather than destitution.[5][2]Expansion During Industrialization and Railroads

The expansion of the U.S. railroad network after the Civil War, which grew from approximately 35,000 miles of track in 1865 to over 193,000 miles by 1900, enabled large-scale mobility for itinerant workers seeking seasonal employment in agriculture, mining, and construction.[14] This infrastructure boom created opportunities for migrant laborers, known as hobos, to hop freight trains and traverse the country, carrying essential belongings in bindles—cloth-wrapped bundles tied to sticks for easy portability during rail travel.[12] The bindle's simple design allowed workers to secure tools, clothing, and provisions without encumbering movement on trains or while walking between rail yards.[3] Industrialization in the late 19th century amplified this trend, as factories and expanding farms demanded flexible labor pools that outpaced local populations, drawing rural workers westward along rail lines.[15] Terms like "bindle stiff" emerged to describe these chronic wanderers, who relied on the bindle for its versatility in enduring long journeys marked by physical hardship and economic uncertainty.[4] By the 1880s and 1890s, the practice had become widespread among an estimated hundreds of thousands of such transients, fueled by economic panics like the Panic of 1893, which displaced workers and increased rail-based migration.[16] Railroad companies' tolerance of riders—often for labor needs—further entrenched bindle use, though detection risks led to innovations in concealment and quick assembly.[17] This era marked the bindle's transition from ad hoc personal bundle to a cultural staple of hobo self-reliance, distinct from urban vagrancy, as workers prioritized functionality for survival in a rapidly industrializing economy.[18]Peak Usage in the Great Depression Era

The Great Depression, triggered by the Wall Street Crash of October 29, 1929, led to widespread unemployment peaking at approximately 25% of the U.S. workforce by 1933, forcing millions into transient lifestyles as they sought employment across the country.[19] This era marked the zenith of bindle usage, as itinerant workers known as hobos bundled their meager possessions—typically spare clothing, canned goods, a razor, and basic tools—into cloth sacks tied to wooden sticks for portability while riding freight trains.[20] Estimates indicate that between 1.5 and 2 million Americans, including about 250,000 teenagers, adopted hobo lifestyles during the 1930s, relying on bindles to transport essentials weighing around 3 pounds for ease during rail hopping and long marches.[21][22] Bindles proved practical for these migrants due to their lightweight construction, allowing quick assembly from scavenged materials like handkerchiefs or bedsheets knotted around a sturdy branch, which doubled as a walking staff and defensive tool against threats such as railroad bulls or wildlife.[23] Historical accounts from the period describe hobos swinging bindles over shoulders to board moving trains, preserving mobility essential for evading detection and covering vast distances—often thousands of miles—in pursuit of seasonal farm work, construction gigs, or odd jobs.[21] The bindle's simplicity contrasted with the era's industrial baggage, suiting the nomadic existence where ownership was minimal and disposability high; lost or stolen bindles were readily replaced, reflecting the precarity of Depression-era survival.[24] Photographic and oral histories from hobo jungles—temporary encampments near rail yards—corroborate the bindle's ubiquity, with transients sharing tips on secure tying methods to prevent spillage during jolting rides.[21] Usage began waning by the late 1930s as New Deal programs like the Civilian Conservation Corps provided structured relief, reducing the scale of rail-riding migration, though bindles remained emblematic of the period's mass displacement until World War II mobilization absorbed much of the transient labor force into wartime industries around 1941.[22]Construction and Practical Use

Materials and Assembly

The bindle was primarily assembled from readily available, durable materials scavenged or repurposed by itinerant workers during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The core components included a square or rectangular piece of cloth, often a bandana, handkerchief, or scrap of blanket, selected for its toughness and ability to withstand weather exposure and rough handling.[25][26] The supporting element was a straight wooden stave or pole, typically 3 to 5 feet in length, sourced from tree branches, broom handles, or discarded lumber to provide balance and leverage for carrying over the shoulder.[25][27] Assembly began by laying the cloth flat and centering the intended contents—such as clothing, tools, or food—upon it to distribute weight evenly and prevent shifting during travel. The four corners of the cloth were then gathered upward and twisted or knotted together at the top to form a secure pouch, with diagonal opposite corners often tied first for stability before securing the remaining pair.[28][26] This bundle was affixed to the stave by looping excess cloth or using cordage, twine, or rope to lash it near one end, allowing the load to hang balanced while slung over the shoulder or gripped in hand for mobility.[25][27] Such methods emphasized simplicity and resourcefulness, enabling quick packing and unpacking without specialized tools, as documented in historical recreations aligned with accounts from the hobo era.[24]Typical Contents and Functionality

The bindle primarily served as a portable bedroll, typically comprising one or more blankets, quilts, or layered newspapers bundled within a square of cloth such as a bandana, bedsheet, or piece of canvas to provide bedding for outdoor sleeping.[29][30] This core contents ensured insulation against cold ground and weather, essential for hobos enduring transient lifestyles. Spare clothing, often limited to a second shirt, pair of socks, or underwear, was commonly included to maintain hygiene and prevent infections from prolonged exposure to damp conditions.[31] Functionally, the bindle enabled efficient transport of minimal possessions over long distances by foot or rail; secured to a stick—frequently a whittled branch or broom handle—it balanced weight across the shoulder, allowing free use of hands for climbing freight trains or labor tasks.[29] The lightweight assembly, weighing around 3 pounds when packed, facilitated quick deployment: untying released the bedroll for immediate rest, while the outer cloth could double as ground cover or rain protection if oiled. Additional items like a pocket knife for cutting food or wire, a tin can or cup for cooking over open fires, and small quantities of non-perishables such as beans or biscuits were occasionally packed, prioritizing utility over bulk to support daily foraging and odd jobs during the Great Depression era (1929–1939).[24][31] This design underscored the bindle's role in embodying self-reliant survival, discardable if pursued by authorities, yet adaptable for the hobo's code of work-seeking mobility.[30]Carrying Methods and Ergonomics

Bindles were primarily carried by attaching a cloth bundle to a wooden stick, typically 1 to 1.5 meters in length, and resting the stick across one shoulder with the bundle suspended behind or to the side of the body. This sling-style method freed both hands for climbing onto freight trains, signaling, or immediate labor upon arrival at job sites, essential for itinerant workers traversing railroads in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[3][32] Ergonomically, the shoulder-borne load shifted weight from the weaker finger and forearm muscles to the broader deltoid and trapezius musculature, while the stick functioned as a fulcrum permitting periodic arm repositioning to alleviate localized pressure. This setup facilitated sustained carrying over distances without constant manual gripping, aligning with the light payloads—often limited to essentials weighing 1-2 kilograms—that minimized torque on the shoulder joint.[33][34] Despite these advantages, the unilateral distribution imposed uneven biomechanical stress, potentially exacerbating spinal curvature or shoulder impingement during prolonged use, especially if the carrier adopted a compensatory stoop. Compared to bilateral carriers like yokes or precursors to backpacks, bindles offered inferior stability for heavier loads but excelled in rapid deployment and discard scenarios, such as evading authorities, prioritizing mobility over load optimization in the hobo lifestyle.[35][33]Cultural and Symbolic Significance

Depictions in Literature and Folklore

In Jack London's The Road (1907), the bindle is portrayed as a practical bundle of blankets and essentials slung over a stick, defining the "bindle-stiff" as a migratory laborer distinct from idle tramps. London, recounting his own 1890s experiences riding freight trains across the United States and Canada, highlights the bindle's vulnerability to theft by "road-kids"—youthful predators targeting transients—and its role in enabling survival amid harsh rail-yard conditions and anti-vagrancy crackdowns.[36] This depiction underscores the bindle's dual function as a portable shelter and a marker of the bearer's precarious work ethic, grounded in London's firsthand observations of economic displacement during industrialization.[6] Hobo autobiographies further illustrate the bindle in literary form, as in Robert W. Bennett's Bindle Stiff: Autobiography of a Super Hobo (circa mid-20th century), where it represents the minimalist toolkit for enduring cross-country journeys, including bedrolls, cooking gear, and scavenged goods essential for self-sufficiency on the rails.[37] Such accounts, often self-published or niche, draw from lived transients' narratives rather than romantic invention, emphasizing the bindle's evolution from ad-hoc cloth wraps to standardized hobo equipment by the early 1900s. In American folklore, the bindle embodies the archetype of the resourceful wanderer, central to oral tales, hobo codes, and songs romanticizing rail-hopping during the Great Depression, as preserved in collections of transient lore.[4] This imagery, evoking freedom amid adversity, permeates hobo "jungle" storytelling—campside yarns of evading bulls (railroad police) with one's bindle intact—and influenced broader cultural myths, including Woody Guthrie's Bound for Glory (1943), which codifies the bindle as a bedroll symbolizing the era's mass migrations.[29] Archival exhibits of hobo artifacts reinforce its folk status, portraying the stick-slung bundle as an enduring icon of folk hobo resilience against systemic poverty, distinct from later cartoonish exaggerations.[38]Representations in Visual Arts and Media

In visual arts, the bindle frequently symbolizes transience and self-reliance in depictions of American itinerant life. Hobo nickel carvings, crafted by transient engravers on U.S. Buffalo nickels between approximately 1915 and 1935, often feature figures shouldering bindles, with the bundled cloth representing essential possessions for rail travel.[39] These pocket-sized artworks, traded or sold for necessities, numbered in the thousands and were concentrated in regions like the Midwest and Pacific Northwest, where hobo populations peaked.[40] Norman Rockwell's 1924 illustration Hobo, published in Country Gentleman, portrays a bindle-carrying youth evoking both romantic wanderlust and economic precarity amid post-World War I shifts.[41] Photographic documentation from the Great Depression era, such as Federal Arts Project prints and Farm Security Administration images, occasionally includes bindles among migrant workers' gear, though less stereotypically than in folk carvings.[42] Tramp art assemblages, using layered cigar box wood from the late 19th to mid-20th century, indirectly evoke bindle aesthetics through portable, scavenged motifs, but rarely depict the device explicitly.[43] In film and animation, the bindle reinforces hobo archetypes as symbols of resilience or downfall. Charlie Chaplin's The Tramp (1915) popularized the image globally, with the protagonist wielding a bindle in slapstick sequences highlighting vagrancy's perils and freedoms.[29] Preston Sturges' Sullivan's Travels (1941) features director Joel McCrea's character assembling a bindle for an undercover hobo odyssey, satirizing Hollywood's romanticization of poverty through montage sequences of rail-hopping and camp life.[44] Later films like Emperor of the North (1973) integrate bindles into gritty portrayals of 1930s freight-train conflicts, emphasizing their practical role in survival.[45] Animation codified the bindle—often stereotypically rendered as a handkerchief tied to a stick—as a visual shorthand for departure, destitution, or runaway characters in mid-20th-century stories, appearing in Warner Bros. Looney Tunes shorts from the 1930s, such as hobo animal characters whistling away with bundled sticks.[46] Disney's The Emperor's New Groove (2000) employs it for comic effect in Kuzco's hobo transformation, while earlier Merrie Melodies like Hobo Bobo (1947) use bindles to anthropomorphize wandering primates, blending humor with Depression-era echoes.[47] This trope persists in modern media, underscoring the bindle's enduring cultural resonance as an emblem of minimalism over settled domesticity.Symbolism in American Identity and Self-Reliance

The bindle served as a potent emblem of self-sufficiency within hobo culture, allowing itinerant workers to transport essential possessions—such as clothing, tools, and provisions—in a compact, makeshift bundle slung over a stick, thereby facilitating constant mobility without reliance on permanent shelter or material excess. This design reflected the hobo's core philosophy of resourcefulness, where survival depended on one's ability to adapt and labor opportunistically, as articulated in the Hobo Ethical Code of 1889, which emphasized pursuing "any honest dollar" through migration and self-directed effort.[48][49] The bindle's simplicity underscored a deliberate rejection of dependency, aligning with the practical necessities of freight-hopping and seasonal employment in industries like railroads and agriculture during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[50] In broader American identity, the bindle evoked the archetype of the rugged individualist, paralleling transcendentalist ideals of personal autonomy and frontier exploration, where the wanderer embodied resilience amid economic flux rather than institutional support. Historians note that hoboes, often portrayed as "bindle stiffs," contrasted with urban tramps by affirming labor's dignity and self-determination, contributing to a mythology of national character rooted in mobility and initiative.[51] This symbolism persisted in cultural narratives, romanticizing the hobo as a voluntary nomad chasing opportunity, much like pioneers traversing unsettled lands, though grounded in the era's labor migrations post-Civil War.[52] By World War I, the bindle's image reinforced perceptions of hoboes as exemplars of "rugged self-reliance" against the perceived idleness of other transients.[51] The bindle's enduring iconography in folklore and media further cemented its role in symbolizing American self-reliance, evoking freedom from entanglement with societal structures while highlighting the burdens of itinerancy—hardship balanced by personal agency. Cultural analyses describe it as a marker of adaptive ingenuity, where minimalism enabled independence, influencing later interpretations in survivalist contexts as a model for carrying one's fate unencumbered.[53] Despite debates over hobo romanticization, the bindle remains a visual shorthand for the valorization of individual effort in the face of adversity, integral to narratives of national exceptionalism tied to labor and wanderlust.[54]Myths, Realities, and Criticisms

Stereotypes Versus Historical Evidence

The stereotypical image of the hobo bindle—a cloth bundle of possessions tied to the end of a stick and slung over the shoulder—has permeated American culture through cartoons, films, and folklore, often portraying it as an emblem of whimsical vagabondage or indolent drifting. This depiction, popularized in the early 20th century, implies a lifestyle of voluntary nomadism detached from societal obligations, sometimes conflating hobos with non-working tramps or bums who begged for sustenance rather than laboring. Such representations, while visually striking, overlook the socioeconomic desperation driving migration, particularly during economic downturns like the post-Civil War era and the Great Depression, when unemployment forced millions into transient work-seeking.[55][14] Historical evidence, drawn from contemporary accounts and photographic records, confirms the bindle's widespread practical use among hobos—defined as itinerant workers pursuing temporary employment—from the 1870s through the 1940s. Migratory laborers, numbering approximately 3 million by 1910 and surging in the 1930s amid 25% national unemployment, fashioned bindles from scavenged cloth or blankets to carry essentials like clothing, tools (e.g., hoes for farm work), and minimal provisions while traveling by foot or freight trains. The stick facilitated over-the-shoulder carrying, reducing strain compared to handheld bags, doubling as a walking staff for long treks between rail lines, and providing rudimentary self-defense against threats like wildlife or hostile railroad "bulls." Unlike the stereotype's implication of leisure, bindle use reflected necessity: hobos maintained a strong work ethic, distinguishing themselves from tramps (who wandered without intent to labor) and bums (who avoided work altogether), often resenting such mischaracterizations in their own conventions and writings.[11][14] Photographic documentation from the era, including images of rail yards and migrant camps, substantiates the bindle-stick configuration as a common, if not universal, sight, though variations existed—some hobos used sacks or bedrolls without sticks for train travel to avoid encumbrance. Women and minority hobos, less visible in stereotypes, also employed similar methods despite added vulnerabilities. This evidence counters romanticized narratives by highlighting the bindle's role in a grueling existence marked by peril: an estimated 10,000-20,000 annual deaths from train accidents or starvation underscored the gap between cultural iconography and the harsh calculus of survival amid industrial displacement and agricultural mechanization.[11][14]Debunking Romanticized Narratives

The portrayal of the bindle as an emblem of unburdened wanderlust and self-sufficient adventure overlooks the grim economic compulsions that propelled most carriers into transient labor. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, waves of displacement from farm mechanization and industrial upheaval forced millions into seasonal migration, with the bindle serving as a rudimentary necessity rather than a chosen badge of freedom; by 1893, economic panic had swelled transient populations to an estimated 500,000 in the U.S., many compelled by job scarcity rather than romantic itinerancy.[12] Hobos distinguished themselves from tramps by seeking employment, yet this ethic masked pervasive desperation, as agricultural and rail work proved intermittent and exploitative, yielding average earnings of mere dollars per day amid widespread destitution.[56] Freight train hopping, mythologized as exhilarating escapade, inflicted lethal hazards that curtailed lives far short of idyllic horizons, with derailments, falls, and confrontations claiming thousands annually; railroad records from the 1920s document over 5,000 trespasser fatalities yearly, disproportionately among transients clinging to boxcars with bindles in tow.[57] Encounters with "bulls"—railroad security—often escalated to brutality, including beatings and shootings, while inter-hobo rivalries over scarce resources bred stabbings and thefts in roadside "jungles," undermining notions of communal harmony.[58] Malnutrition, exposure, and untreated ailments compounded mortality, with hobo demographics skewing toward men in their 20s and 30s succumbing by middle age, as corroborated by coroner reports from era encampments revealing rampant tuberculosis and alcoholism-fueled decline.[29] Symbols like the purported "Hobo Code"—hieroglyphs allegedly marking safe havens—exemplify folklore amplification over empirical practice, with scant archaeological or documentary evidence beyond anecdotal 20th-century claims, likely embellished in literary accounts to lend ethos to a subculture riven by survival imperatives rather than codified ethics.[11] Jack London's 1907 The Road, blending autobiography and invention, popularized such motifs but confessed the author's own bouts of privation and deceit, revealing how narratives glamorized predation and begging as "casing joints" for alms.[29] In truth, bindle use reflected makeshift portability amid chronic insecurity, not philosophical minimalism; many abandoned sticks for sacks due to imbalance and vulnerability to rifling, as practical accounts from the era attest, dispelling the archetype's veneer of effortless prowess.[56] This disconnect persists in modern media, where hobo iconography evokes Kerouacian liberation, yet causal analysis traces it to structural failures—absent welfare or mobility alternatives—yielding a transient class more akin to economic refugees than vanguard individualists.Associations with Vagrancy and Work Ethic

The bindle, carried by itinerant workers known as hobos during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, became emblematic of vagrancy in American public perception, as transients were often arrested under vagrancy statutes that criminalized unemployment and rootlessness among able-bodied men.[52][59] Historical records indicate that by the 1870s, economic disruptions from industrialization and railroad expansion displaced skilled laborers, leading to widespread migration; hobos, estimated at up to 2 million during the Great Depression era around 1930, hopped freight trains illegally, fostering views of them as societal threats despite their pursuit of seasonal employment in agriculture, construction, and railroads.[60][61] Vagrancy laws, rooted in post-Civil War efforts to control labor mobility, disproportionately targeted these migrants, equating transience with idleness even when evidence showed many contributed to essential industries.[59] In contrast to stereotypes of laziness, hobo culture self-identified through a robust work ethic, distinguishing hobos from tramps—who wandered without seeking employment—and bums—who remained stationary and idle.[12][11][16] Hobos adhered to informal codes, such as the purported Hobo Ethical Code originating around 1889, which prioritized honest labor, self-reliance, and aiding fellow workers, reflecting a Protestant-influenced valorization of productivity amid economic hardship.[62][63] Primary accounts from the period, including hobo conventions and signage systems, underscore this ethos: symbols marked safe work sites and warned of exploitative employers, enabling efficient job-seeking across regions.[11] These dual associations reveal tensions in historical discourse, where media and authorities often conflated hobos with criminal vagrants, amplifying fears of social disorder, while hobo narratives themselves emphasized dignity through labor to counter such biases.[17][64] Empirical data from labor histories indicate that many bindle-carrying migrants filled critical gaps in the workforce, such as harvesting crops or building infrastructure, challenging blanket condemnations of their lifestyle as antithetical to industry.[65] Over time, however, the term "hobo" evolved derogatorily to encompass non-working vagrants, diluting recognition of the original work-oriented archetype.[66]Decline and Modern Interpretations

Post-World War II Decline

The bindle's use declined precipitously after World War II, coinciding with the erosion of the hobo subculture that had popularized it as a symbol of itinerant labor. Post-war economic prosperity, driven by industrial expansion and consumer demand, created widespread stable employment opportunities, obviating the need for the seasonal migrant work that necessitated lightweight, portable bindles for rail and foot travel. Unemployment rates, which stood at 1.9% in 1945 and rose modestly to 3.9% in 1946 amid demobilization, reflected near-full employment that drew former transients into fixed jobs rather than wandering.[67][68] Technological shifts in railroading accelerated this trend, as the industry's conversion from steam to diesel locomotives—beginning in earnest after 1945—rendered freight-hopping far riskier and less viable. Diesel engines lacked the accessible coal tenders and slower operation of steam models, which had facilitated hobo mobility and the bindle's role in carrying essentials during jumps; instead, they introduced smoother exteriors, higher speeds, and enhanced railroad policing, effectively dismantling the infrastructure supporting bindle-dependent travel.[29] Municipal efforts to modernize urban areas further marginalized hobo encampments, where bindles were often stored or assembled. Clearance of "hobo jungles"—informal rail-side settlements—intensified post-war, with sites repurposed for parks and development; in Mansfield, Ohio, for example, former jungle land along Route 30 was converted into a roadside park shortly after 1945, symbolizing the broader societal push toward settled, productive lifestyles over vagrancy.[69][70]Contemporary Uses in Survivalism and Recreation

In modern bushcraft and survival training, the bindle serves as a minimalist carrying device for enthusiasts seeking to emulate primitive load-hauling techniques during short wilderness expeditions or skill-building exercises. Typically constructed from a bandana or cloth sack tied to a sturdy stick—often 4 to 5 feet long— it allows hands-free transport of lightweight essentials like cordage, fire-starting tools, small knives, and dehydrated rations, weighing under 10 pounds for optimal balance.[71] This method prioritizes mobility over capacity, enabling users to navigate trails or evade detection in stealth camping scenarios, as demonstrated in practical guides where the bindle is slung over the shoulder to distribute weight evenly across the body.[72] Proponents argue it fosters reliance on basic materials available in natural environments, contrasting with bulkier modern packs, though empirical tests show it fatigues shoulders faster on extended hikes exceeding 10 miles.[73] Recreational hikers and historical reenactors have adopted the bindle for low-impact outings, such as day treks or hobo-style overnights, where it bundles sleeping rolls, cookware, and minimal clothing to evoke early 20th-century transient lifestyles. In the United Kingdom, solo campers have documented using bindles paired with wool bedrolls for bare-minimum wild camping, carrying gear under 5 kilograms to test endurance in varied terrains like forests or moors.[74] Bushcraft communities online, including forums dedicated to primitive skills, promote DIY bindle projects as entry-level crafts, often using forked sticks reminiscent of ancient Roman furca for added stability, to teach knot-tying and resource improvisation without specialized equipment.[75] While not a staple in formal prepper kits—where structured bug-out bags prevail for organized access—the bindle's appeal lies in its ultra-portability for urban-to-wilderness transitions, as seen in compact survival kits designed to "ride bindle-style" in coat pockets or small bundles.[76] Commercial adaptations, such as pre-made bindle kits from specialty outfitters, cater to recreational users by pairing sustainably sourced sticks with durable bandanas, marketed for camping, gym transitions, or casual travel, though these diverge from traditional designs by emphasizing capacity up to 75 pounds for non-stick variants.[77] Overall, adoption remains niche, confined to hobbyists valuing historical authenticity over ergonomic efficiency, with no widespread empirical data indicating superiority to contemporary alternatives like ultralight daypacks in load distribution or weather resistance.[78]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/bindle