Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Body shape

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2015) |

| Part of a series on |

| Human body weight |

|---|

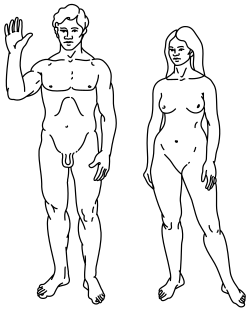

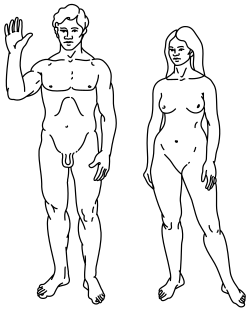

Human body shape is a complex phenomenon with sophisticated detail and function. The general shape or figure of a person is defined mainly by the molding of skeletal structures, as well as the distribution of muscles and fat.[1] Skeletal structure grows and changes only up to the point at which a human reaches adulthood and remains essentially the same for the rest of their life. Growth is usually completed between the ages of 13 and 18, at which time the epiphyseal plates of long bones close, allowing no further growth (see Human skeleton).[2]

Many aspects of body shape vary with gender and the female body shape especially has a complicated cultural history. The science of measuring and assessing body shape is called anthropometry.

Physiology

[edit]During puberty, differentiation of the male and female body occurs for the purpose of reproduction. In adult humans, muscle mass may change due to exercise, and fat distribution may change due to hormone fluctuations. Inherited genes play a large part in the development of body shape.

Facial features

[edit]Due to the action of testosterone, males may develop these facial-bone features during puberty:

- A more prominent brow bone (bone across the centre of the forehead from around the middle of eyebrow across to the middle of the other) and a larger nose bone.[3]

- A heavier jaw.

- A high facial width-to-height ratio.[4] However some studies dispute this, and testosterone reduces cheekbone prominence in males.[5]

- A more prominent chin.

Because females have around 1/15 (6.67%) the amount of testosterone of a male,[6] the testosterone-dependent features do not develop to the same extent, and thus female faces are generally less changed from to those of pre-pubertal children.

Skeletal structure

[edit]Skeletal structure frames the overall shape of the body and does not alter much after maturity. Males are, on average, taller, but body shape may be analyzed after normalizing with respect to height. The length of each bone is constant, but the joint angle will change as the bone moves.[7] The dynamics of biomechanical movement will be different depending on the pelvic morphology for the same principle. The fascia anatomy of the sides of the sacral diamond area, which regulates its shape and movement, corresponds to the fascial thickenings that are part of the sacral complex of the thoracambular fascia, which surrounds the sacroiliac joints both posteriorly and, from the iliolumbar ligaments, anteriorly. The biochemical properties of the muscular bands have repercussions from the inside to the outside and vice versa.[8] The shape of the posterior muscular and adipose tissues seems to correspond with the general pelvic morphology. The classification is as follows the gynecoid pelvis corresponds to a round buttocks shape, the platypelloid pelvis to a triangle shape, the anthropoid pelvis to a square shape and the android pelvis to a trapezoidal gluteus region.[8] The trapezoidal shape is what gives steatopygia its specific shape and appearance.[citation needed]

Female traits

[edit]Widening of the hip bones occurs as part of the female pubertal process,[9] and estrogens (the predominant sex hormones in females) cause a widening of the pelvis as a part of sexual differentiation. Hence females generally have wider hips, permitting childbirth. Because the female pelvis is flatter, more rounded and proportionally larger, the head of the fetus may pass during childbirth.[10] The sacrum in females is shorter and wider, and also directed more toward the rear (see image).[11] This sometimes affects their walking style, resulting in hip sway.[12] The upper limb in females have an outward angulation (carrying angle) at elbow level to accommodate the wider pelvis. After puberty, hips are generally wider than shoulders. However, not all females adhere to this stereotypical pattern of secondary sex characteristics.[13] Males and females generally have the same hormones, but blood concentrations and site sensitivity differs between males and females. Males produce primarily testosterone with small amounts of estrogen and progesterone, while women produce primarily estrogen and progesterone and small amounts of testosterone.[14]

Male traits

[edit]

Widening of the shoulders occurs as part of the male pubertal process.[9] Expansion of the ribcage is caused by the effects of testosterone during puberty.[citation needed]

Fat distribution, muscles and tissues

[edit]

Body shape is affected by body fat distribution, which is correlated to current levels of sex hormones.[1] Unlike bone structure, muscles and fat distribution may change from time to time, depending on food habits, exercises and hormone levels.

Fat distribution

[edit]Estrogen causes fat to be stored in the buttocks, thighs, and hips in females.[15] When females reach menopause and the estrogen produced by ovaries declines, fat migrates from their buttocks, hips and thighs to their waists.[16] Later fat is stored in the belly, similar to males.[17] Thus females generally have relatively narrow waists and large buttocks, and this along with wide hips make for a wider hip section and a lower waist–hip ratio compared to males.[18]

Estrogen increases fat storage in the body, which results in more fat stored in the female body.[19] Body fat percentage guidelines are higher for females,[20] as this may serve as an energy reserve for pregnancy.[21] Males generally deposit fat around waists and abdomens (producing an "apple shape").[citation needed]

Transgender men and those who begin masculinizing hormone therapy see body fat redistributed within 3–6 months. Within 5 years, testosterone may cause gynoid fat to be significantly reduced.[22][23] Inversely, transgender women, or those who begin feminizing hormone therapy, experience the formation of gynoid fat along with natural breast development.[23]

Muscles

[edit]Testosterone helps build and maintain muscles through exercise. On average, men have around 5-20 times more testosterone than women and naturally and biologically males gain more muscle mass and size than women.[24] However, women can also build muscle mass by increasing the testosterone level naturally.[25] Prominent muscles of the body include the latissimus dorsi and trapezius in the back, pectoral muscles and rectus abdominis (abdomen) in the chest and stomach respectively, as well as biceps and triceps in the arms and gluteus maximus, quadriceps and hamstrings in the thighs.[26]

Breasts

[edit]Females have breasts due to functional mammary glands, which develop in puberty from the influence of various hormones such as thyroxine, cortisol, progesterone, estrogen, insulin, prolactin, and human growth hormone.[27] Mammary glands do not contain muscle tissue. The shape of female breasts is affected by age, genetic factors, and body weight. Women's breasts tend to grow larger after menopause, due to increase in fatty deposits caused by decreasing levels of estrogen. The loss of elasticity from connective tissue associated with menopause also causes sagging.[28]

Weight

[edit]Being overweight or underweight affects the human body's shape as well as posture and walking style.[citation needed] This is measured using Body Mass Index (BMI). Depending on the BMI, a body may be referred to as underweight, normal, overweight, or obese. A person with a BMI below 18.5 is classed as underweight, between 18.5 and 24.9 is ideal, above 24.9 is overweight and a BMI of 30 or higher is defined as obese.[29]

Body posture and gait

[edit]Body shape has effects on body posture[30] and gait, and has a major role in physical attraction. This is because a body's shape implies an individual's hormone levels during puberty, which implies fertility, and it also indicates current levels of sex hormones.[1] A pleasing shape also implies good health and fitness of the body. Posture also affects body shape as different postures significantly alter body measurements, which thus can alter a body's shape.[30][31]

Impact on health

[edit]According to the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, those people with a larger waist (apple shaped) have higher health risks than those who carry excess weight on the hips and thighs (pear shaped). People with apple shaped bodies who carry excess weight are at greater risk of high blood pressure, Type 2 diabetes and high cholesterol.[32] The United Kingdom's National Institute for Health and Care Excellence advises that a person's waist-to-height ratio (WtHR) should not exceed 0.5, and that this rule applies to everyone from the age of five and is irrespective of gender, ethnicity or BMI.[33]

Fitness and exercise

[edit]Different forms of exercises are practiced for the fitness of the body and also for health. It is a common belief that targeted exercise reduces fat in specific parts of the body —for example, that exercising muscles around the belly reduces fat in the belly. This, however, is now proven to be a misconception; these exercises may change body shape by improving muscle tone but any fat reduction is not specific to the locale. Spot reduction exercises are not useful unless you plan proper exercise regime to lose overall calories. But exercising reduces fat throughout the body, and where fat is stored depends on hormones. Liposuction is surgery commonly used in developed societies to remove fat from the body.

Social and cultural ideals

[edit]The general body shapes of female and male bodies both have significant social and cultural symbolism. Physical attractiveness is closely associated with traits that are considered typical of either sex.[38] The body mass index (BMI), waist-to-hip ratio, and especially waist-to-chest ratio in men have been shown in studies to rank as overall more desirable to women. To be deemed to have an "athletic built"/build[39] is usually a reference to wide shoulders, a muscular upper body and well-developed upper-arm muscles which are all traits closely associated with masculinity, similarly to other specifics of the male sex, like beards. These traits are seen more sexually attractive to women and also associated with higher intelligence, good leadership qualities and better health.[40]

Terminology

[edit]Classifications of female body sizes are mainly based on the circumference of the bust–waist–hip (BWH), as in 90-60-90 (centimeters) or 36–24–36 (inches) respectively. In this case, the waist–hip ratio is 60/90 or 24/36 = 0.67. Many terms or classifications are used to describe body shape types:

- V shape: Males tend to have proportionally smaller buttocks, bigger chests and wider shoulders, wider latissimus dorsi and a small waist which makes for a V-shape of the torso.

- Hourglass shape: The female body is significantly narrower in the waist both in front view and profile view. The waist is narrower than the chest region due to the breasts, and narrower than the hip region due to the width of the buttocks, which results in an hourglass figure.

- Apple: The stomach region is wider than the hip section, mainly in males.

- Pear or spoon or bell: The hip section is wider than the upper body, mainly in females.[citation needed]

- Rectangle or straight or banana: The hip, waist, and shoulder sections are relatively similar.

See also

[edit]- Body image – Aesthetic perception of one's own body

- Body proportions – Proportions of the human body in art

- Body mass index – Relative weight based on mass and height (BMI)

- Body roundness index – Body scale based on waist circumference and height (BRI)

- Bust/waist/hip measurements – Measures used for fitting clothing ("Vital statistics")

- Dad bod – Slang term for a body shape particular to middle-aged men

- Female body shape – Characteristic of human females

- Human gait – Pattern of limb movements made during locomotion

- Human physical appearance – Look, outward phenotype

- Phenotype – Composite of the organism's observable characteristics or traits

- List of human positions – Physical configurations of the human body

- Human skeleton – Internal framework of the human body

- Sex differences in humans – Difference between males and females

- Sexual dimorphism – Evolved difference in sex-specific characteristics

- Somatotype and constitutional psychology – Taxonomy to categorize human physiques

- Eugenics – Effort to improve purported human genetic quality (discredited fringe theory)

- Waist–hip ratio

- Waist-to-height ratio

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Singh D (2007). "An Evolutionary Theory of Female Physical Attractiveness". Psi Chi. The National Honor Society in Psychology. Archived from the original on 2007-07-05. Retrieved 2011-10-09.

- ^ "Lateral Synovial Joint Loading Explained In Simple English". 19 August 2012. Archived from the original on 2021-01-26. Retrieved 2021-01-31.

- ^ Perrett DI, Lee KJ, Penton-Voak I, Rowland D, Yoshikawa S, Burt DM, et al. (August 1998). "Effects of sexual dimorphism on facial attractiveness". Nature. 394 (6696): 884–887. Bibcode:1998Natur.394..884P. doi:10.1038/29772. PMID 9732869. S2CID 204999982.

- ^ Holden C (August 20, 2008). "The Face of Aggression". Science. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ^ Hodges-Simeon, Carolyn R.; Sobraske, Katherine N. Hanson; Samore, Theodore (14 April 2016). "Facial Width-To-Height Ratio (fWHR) Is Not Associated with Adolescent Testosterone Levels". PLOS ONE. 11 (4) e0153083. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1153083H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0153083. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4831733. PMID 27078636.

"Specifically, facial width/lower face height gets smaller (i.e., the lower face grows more than the width of the face), cheekbone prominence gets smaller (i.e., the width of the face at the mouth—a measure of relative jaw width—grows more than the width of the cheekbones), and lower face height/full face height gets larger (i.e., facial growth is focused in the lower face) as male adolescents develop. These results are consistent with the craniofacial literature that documents pronounced growth in the male mandible under the influence of exogenous T [51] and during puberty [83–85]. Similarly, the association between T and these mandible-inclusive facial ratios accords with Lefevre et al. [16], who found significant sexual dimorphism in these three ratios, but no adult sex difference in fWHR." See Table 1 and Figure 2 for cheekbone relation to testosterone levels.

- ^ Handelsman, David J; Hirschberg, Angelica L; Bermon, Stephane (October 2018). "Circulating Testosterone as the Hormonal Basis of Sex Differences in Athletic Performance". Endocrine Reviews. 39 (5): 803–829. doi:10.1210/er.2018-00020. PMC 6391653. PMID 30010735.

- ^ Saeki T, Furukawa T, Shimizu Y (1997). "Dynamic clothing simulation based on skeletal motion of the human body". International Journal of Clothing Science and Technology. 9 (3): 256–263. doi:10.1108/09556229710168414. ISSN 0955-6222.

- ^ a b Siccardi, Marco A.; Imonugo, Onyebuchi; Arbor, Tafline C.; Valle, Cristina (2025), "Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Pelvic Inlet", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 30085610, retrieved 2025-01-21

- ^ a b "Reproductive Anatomy and Physiology". The Harriet and Robert Heilbrunn Department of Population and Family Health. Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. Retrieved 2011-10-09.

Secondary sexual characteristics occur as part of the pubertal process

- ^ See Gender differences in Human skeleton and Sexual dimorphism in Hips

- ^ Saukko P, Knight B (2004). Knight's Forensic Pathology (3rd ed.). Edward Arnold Ltd. ISBN 0-340-76044-3.

- ^ "Clues To Mysteries Of Physical Attractiveness Revealed". ScienceDaily. 24 May 2007. Retrieved 2011-10-09.

- ^ Haeberle EJ. "The secondary sexual characteristics". The Sex Atlas. Archived from the original on 2011-09-27. Retrieved 2011-10-09.

Hips grow wider than their shoulders

- ^ Lauretta, R; Sansone, M; Sansone, A (2018). "Gender in Endocrine Diseases: Role of Sex Gonadal Hormones". International Journal of Endocrinology. 2018 4847376. doi:10.1155/2018/4847376. PMC 6215564. PMID 30420884.

Generally, females and males have the same hormones (i.e., estrogens, progesterone, and testosterone), but their production sites, their blood concentrations, and their interactions with different organs, systems, and apparatus are different [29]. Males produce predominantly testosterone from the testes in a relatively constant daily amount according to a circadian profile. Small amounts of estrogens and progesterone are produced by the testes and the adrenal glands or are produced in the peripheral tissues, such as adipose tissue or liver, by the conversion of other precursor hormones [30]. In contrast, females mainly produce estrogens and progesterone from the ovaries in a cyclical pattern, while a small amount of testosterone (T) is produced by the ovaries and adrenal glands.

- ^ Peeke PM. "Waistline Worries: Turning Apples Back Into Pears". National Women's Health Resource Center. Archived from the original on 2009-06-09.

- ^ "Women's Health". Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ "Abdominal fat and what to do about it". Archived from the original on 2011-09-28. Retrieved 2007-06-18.

- ^ "Why men store fat in bellies, women on hips". The Times of India. 2011-01-03. Archived from the original on 2012-01-14. Retrieved 2011-10-09.

- ^ "Sex hormone making women fat?". The Times of India. 2009-04-07. Archived from the original on 2011-08-11. Retrieved 2011-10-09.

- ^ "QuickStats: Mean Percentage Body Fat,* by Age Group and Sex --- National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, United States, 1999--2004†". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2022-11-03.

- ^ Most J, Dervis S, Haman F, Adamo KB, Redman LM (August 2019). "Energy Intake Requirements in Pregnancy". Nutrients. 11 (8): 1812. doi:10.3390/nu11081812. PMC 6723706. PMID 31390778.

- ^ "Masculinizing hormone therapy - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Retrieved 2024-10-03.

- ^ a b Unger, Cécile A. (December 2016). "Hormone therapy for transgender patients". Translational Andrology and Urology. 5 (6): 877–884. doi:10.21037/tau.2016.09.04. ISSN 2223-4691. PMC 5182227. PMID 28078219.

- ^ Kopala, Mary; Keitel, Merle (11 July 2003). Handbook of Counseling Women. SAGE Publications. p. 94. ISBN 978-1-4522-6285-7.

- ^ Tiidus, PM (August 2011). "Benefits of estrogen replacement for skeletal muscle mass and function in post-menopausal females: evidence from human and animal studies". The Eurasian Journal of Medicine. 43 (2): 109–14. doi:10.5152/eajm.2011.24. PMC 4261347. PMID 25610174.

- ^ Applegate, Edith MS (25 February 2009). The Sectional Anatomy Learning System - E-Book: Concepts and Applications 2-Volume Set. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-323-27754-9.

- ^ Fritz, Marc A.; Speroff, Leon (28 March 2012). Clinical Gynecologic Endocrinology and Infertility. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 624. ISBN 978-1-4511-4847-3.

- ^ Sabel, Michael S. (23 April 2009). Essentials of Breast Surgery: A Volume in the Surgical Foundations Series E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-323-07464-3.

- ^ The SuRF Report 2 (PDF). The Surveillance of Risk Factors Report Series (SuRF). World Health Organization. 2005. p. 22. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ a b Gill S, Parker CJ (August 2017). "Scan posture definition and hip girth measurement: the impact on clothing design and body scanning". Ergonomics. 60 (8): 1123–1136. doi:10.1080/00140139.2016.1251621. PMID 27764997. S2CID 23758581.

- ^ Parker CJ, Hayes SG, Brownbridge K, Gill S (August 2021). "Assessing the female figure identification technique's reliability as a body shape classification system". Ergonomics. 64 (8): 1035–1051. doi:10.1080/00140139.2021.1902572. PMID 33719914. S2CID 232231822.

- ^ "Assess your weight". Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. Archived from the original on 2011-08-25. Retrieved 2011-10-09.

- ^ "Obesity: identification and classification of overweight and obesity (update) Recommendations 1.2.25 and 1.2.26". National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 2022.

- ^ "People: Just Deserts". Time. May 28, 1945. Archived from the original on August 11, 2009. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

... "the most perfect all-over beauty of all time." Runner-up: the Venus de Milo.

- ^ "Says Venus de Milo was not a Flapper; Osteopath Says She Was Neurasthenic, as Her Stomach Was Not in Proper Place" (PDF). The New York Times. April 29, 1922. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

Venus de Milo ... That lady of renowned beauty...

- ^ CBS News Staff (August 5, 2011). "Venus". CBS News. Archived from the original on January 29, 2010. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

The classical vision of beauty exemplified in Greek art, such as the 2nd century B.C. Venus de Milo (a.k.a. Aphrodite of Milos), was an ideal carried through millennia, laying the basis for much of Western art's depictions of the human form.

- ^ Kousser R (2005). "Creating the Past: The Vénus de Milo and the Hellenistic Reception of Classical Greece". American Journal of Archaeology. 109 (2): 227–50. doi:10.3764/aja.109.2.227. S2CID 36871977.

- ^ Pazhoohi, Farid; Garza, Ray; Kingstone, Alan (2023). "The Interacting Effects of Height and Shoulder-to-Hip Ratio on Perceptions of Attractiveness, Masculinity, and Fighting Ability: Experimental Design and Ecological Validity Considerations". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 52 (1): 301–314. doi:10.1007/s10508-022-02416-2. PMID 36074312.

- ^ Williams LA (May 2012). Resurfaced. Lulu.com. ISBN 978-1-105-71303-3. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

...and athletic built

- ^ Swami V (2006). "The Influence of Body Weight and Shape in Determining Female and Male Physical Attractiveness". In Kindes MV (ed.). Body Image: New Research. New York: Nova Publishers. pp. 36–51. ISBN 978-1-60021-059-4.

External links

[edit]Body shape

View on GrokipediaBeyond aesthetics and reproduction, body shape carries causal health implications: android (central) fat patterns, more common in males, elevate risks for insulin resistance, hypertension, and cardiovascular events due to lipotoxicity in visceral depots, whereas gynoid (peripheral) distributions offer relative metabolic protection through safer lipid storage.[1] Genetic heritability underpins much of this variance, with twin studies estimating 40-70% contributions to fat distribution and somatotype components like endomorphy (fat proneness), though environmental factors such as diet and activity modulate expression.[8][9] Controversies arise in interpreting shape ideals, where empirical data on WHR's universality challenge culturally relativistic views, underscoring biology's primacy over transient norms in shaping preferences and outcomes.[7][10]

Biological Determinants

Genetic and Epigenetic Factors

Genetic factors substantially influence human body shape, including skeletal proportions, muscle fiber composition, and adipose tissue distribution patterns, as evidenced by twin studies demonstrating high heritability for these traits. For instance, heritability estimates for body mass index (BMI), a proxy for overall body composition, range from 57% to 80% in adult populations, with genetic influences appearing stronger in childhood. Similarly, multivariate analyses of somatotype components—ectomorphy (linearity), mesomorphy (muscularity), and endomorphy (roundness)—reveal heritabilities of approximately 0.70-0.90 for mesomorphy and ectomorphy in adolescents and adults, indicating robust genetic contributions to morphological variance beyond environmental factors. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) further identify specific loci, such as those near genes expressed in adipose tissue (e.g., TBX15-WARS2 region), that regulate regional fat deposition and contribute to variations in waist-to-hip ratio and visceral adiposity, independent of total body fat.[11][12][13][14] Epigenetic mechanisms, including DNA methylation and histone modifications, modulate gene expression in response to environmental cues, thereby influencing body shape phenotypes such as fat distribution and propensity for obesity without altering the underlying DNA sequence. In adipose tissue, distinct methylation patterns correlate with gynoid versus android fat storage, where visceral fat depots exhibit hypermethylation of genes involved in lipid metabolism, potentially predisposing individuals to central obesity. Obesity-induced epigenetic changes, such as altered methylation of adipogenesis-related loci, can persist post-weight loss, creating a "memory" effect that sustains elevated fat deposition tendencies through modified expression of inflammatory and metabolic pathways. These modifications interact with genetic predispositions; for example, variants in the NAT2 locus, combined with epigenetic silencing of nearby regulatory elements, enhance visceral fat accumulation. Twin discordance studies underscore this interplay, as identical twins with divergent body shapes often show environment-driven epigenetic differences superimposed on shared genotypes.[15][16][17][18]Hormonal Influences

Sex hormones, principally testosterone and estradiol (a form of estrogen), are primary regulators of sexual dimorphism in human body shape, influencing skeletal growth, muscle hypertrophy, and adipose tissue distribution via receptor-mediated gene expression in target tissues. In males, circulating testosterone concentrations, typically 10-20 times higher than in females (ranging 300-1000 ng/dL versus 15-70 ng/dL), drive androgen receptor activation that enhances protein synthesis and satellite cell proliferation in skeletal muscle, resulting in 30-40% greater overall lean body mass and disproportionate upper-body musculature compared to females. This contributes to narrower hips relative to shoulders, with waist-to-hip ratios averaging 0.9 in males.[19][20] In females, estradiol predominates (30-400 pg/mL cyclically), promoting estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) signaling that favors gluteofemoral subcutaneous fat deposition over visceral accumulation, yielding a characteristic lower-body emphasis ("pear" shape) with waist-to-hip ratios around 0.7-0.8 premenopause; this pattern provides metabolic buffering against cardiometabolic risks associated with central obesity.[21][22] Estradiol also modulates skeletal morphology by accelerating epiphyseal plate closure during puberty, limiting long-bone growth in females while facilitating pelvic widening through increased subchondral bone formation and ligament laxity, achieving a 20-30% wider bi-iliac breadth than in males adjusted for height. Testosterone supports male skeletal robustness via direct anabolic effects on periosteal apposition, enhancing cortical bone thickness in limbs and torso for load-bearing adaptation. Evidence from hormone replacement in hypogonadal states confirms these roles: testosterone administration in men increases lean mass by 5-10% and reduces fat mass within months, while estrogen therapy in postmenopausal women shifts fat distribution gynoid-ward and preserves bone mineral density (BMD), with lumbar spine BMD rising 3-4% over 6-12 months.[23][24] Beyond sex steroids, growth hormone (GH) and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) influence body composition by stimulating chondrocyte proliferation in growth plates and myoblast differentiation, promoting linear growth and lean mass accrual during development; GH deficiency yields increased adiposity (up to 20-30% higher body fat percentage) and reduced extracellular water, while replacement therapy decreases fat mass by 5-15% and elevates lean mass equivalently in adults. Cortisol, elevated in chronic stress, preferentially expands visceral adipose via glucocorticoid receptor upregulation of lipogenic enzymes like 11β-HSD1 in omental fat, correlating with android obesity and insulin resistance. Insulin facilitates nutrient partitioning toward storage, exacerbating central fat in hyperinsulinemic states, whereas thyroid hormones (T3/T4) accelerate basal metabolism, with hypothyroidism linked to 5-10% higher body fat and altered distribution toward generalized accumulation. These non-sex hormones interact with steroids; for instance, estrogen attenuates cortisol's visceral effects premenopause, a protection lost post-ovariectomy or menopause, underscoring causal hierarchies in shape determination.[25][26][27]Sex Differences in Morphology

Human males and females exhibit pronounced sexual dimorphism in body morphology, characterized by differences in skeletal proportions, muscular development, and adipose tissue distribution that arise primarily from genetic and hormonal influences during development. Males typically display a more linear, robust build with broader shoulders, narrower hips, and greater overall stature, resulting in an inverted triangular torso shape, while females tend toward a more curvaceous form with narrower shoulders, wider hips, and relatively shorter limbs, contributing to a pear or hourglass silhouette. These patterns are evident across populations and are supported by anthropometric data showing average male shoulder-to-hip ratios of approximately 1.4:1 compared to 0.8:1 in females.[28][29] Skeletal morphology underscores these differences, with males possessing larger, denser bones and a narrower pelvis adapted for locomotion efficiency, featuring a subpubic angle averaging 70 degrees versus 90-100 degrees in females, whose wider pelvic inlet and outlet facilitate childbirth. Male crania and long bones are more robust, with greater overall mass and length; for instance, adult male femurs average 5-10% longer than female counterparts relative to height, contributing to proportionally longer legs. Female skeletons, by contrast, show increased pelvic flare and a more pronounced lumbar lordosis to accommodate the center of gravity shift from gluteofemoral fat deposits. These dimorphisms emerge postnatally and intensify during puberty, driven by sex-specific growth trajectories where estrogen accelerates epiphyseal closure in females, limiting linear growth earlier than in males.[30][31][32] Muscular composition further differentiates male morphology, with males averaging 40-50% greater lean body mass and higher proportions of fast-twitch fibers, leading to thicker limbs and a V-shaped taper from pronounced deltoid and trapezius development. Females, conversely, have relatively greater type I slow-twitch fibers and lower absolute muscle volume, particularly in the upper body, resulting in slimmer arms and a less angular shoulder girdle. Adipose morphology aligns with reproductive priorities: males accumulate visceral and android fat centrally, elevating waist-to-hip ratios above 0.9, whereas females preferentially store subcutaneous gynoid fat in the hips and thighs, maintaining ratios below 0.85 and enhancing pelvic width visually. These distributions persist into adulthood, with females holding 20-30% higher body fat percentages on average, influencing overall contour and metabolic profiles.[33][34][35] Such morphological variances are not absolute, exhibiting overlap due to genetic diversity and environmental factors, yet population-level patterns hold across studies, with dimorphism indices indicating moderate to high effect sizes (e.g., Cohen's d > 1.0 for pelvic metrics). Anthropometric surveys, including those from diverse ethnic groups, confirm consistency, though modern sedentarism may attenuate some muscular disparities without altering skeletal foundations.[36][37]Anatomical Components

Skeletal Structure

The human skeletal structure establishes the primary framework for body shape by dictating bone lengths, widths, joint configurations, and overall proportions. Variations in skeletal morphology, particularly sexual dimorphism, profoundly influence silhouette and regional dimensions, such as shoulder-to-hip ratios. Males typically exhibit larger skeletons with greater bone mass, longer long bones, and increased cortical thickness, resulting in broader shoulders and a narrower pelvis relative to body size.[4][38] Females possess relatively smaller and less robust frames, with adaptations in the pelvis prioritizing obstetric function over mechanical strength.[30] These differences emerge primarily during puberty under hormonal regulation but are genetically predetermined.[39] Appendicular skeletal elements, including the clavicles, scapulae, humeri, and femora, contribute to limb proportions and girdle breadths. Male clavicles average 15-20% longer than female counterparts, enhancing shoulder width and fostering a V-shaped torso taper.[40] Pelvic architecture exemplifies dimorphism: the female pelvis features a wider greater pelvis (bi-iliac diameter approximately 28-30 cm in adults) and a shallower true pelvis with an oval inlet, contrasting the male's narrower (25-27 cm bi-iliac) and heart-shaped inlet for enhanced pelvic canal volume during gestation.[41] The subpubic angle measures 50-60 degrees in males versus 80-85 degrees in females, with females also displaying a wider sciatic notch and everted ilia.[42] Axial components, such as vertebral curvature and rib cage dimensions, further modulate thoracic width, with males showing deeper chests and straighter spines on average.[43] Skeletal frame variations also underpin somatotype classifications, where ectomorphic builds correlate with slender long bones and narrower girdles, mesomorphic with medium-proportioned robusticity, and endomorphic with stockier, denser bones—though soft tissues modify phenotypic expression.[44] Population-level differences exist, but sexual dimorphism accounts for the majority of variance in shape-defining metrics like the waist-to-hip skeletal ratio, independent of adiposity.[45] These structural traits remain stable post-maturity, barring pathological changes, and directly constrain muscular and adipose distributions.[33]Fat Distribution Patterns

Human adipose tissue is distributed across subcutaneous and visceral compartments, with the former comprising approximately 80-90% of total fat in lean individuals and the latter concentrated around internal organs. Subcutaneous fat forms layers beneath the skin, primarily in the abdomen, thighs, and buttocks, while visceral fat accumulates intra-abdominally, surrounding organs like the liver and intestines. These distributions vary significantly by sex, with males exhibiting a higher proportion of visceral adipose tissue (VAT) relative to subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT), often quantified as VAT comprising 10-20% of total fat mass in men compared to 5-10% in premenopausal women.[34][46] In males, fat distribution follows an android pattern, characterized by central accumulation in the abdominal region, including both visceral depots and deeper subcutaneous layers around the trunk. This pattern results in a higher waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), typically exceeding 0.9, reflecting preferential storage in upper body areas that correlates with greater android/gynoid fat ratios measured via dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). Females, conversely, display a gynoid pattern, with greater SAT deposition in the gluteofemoral region (hips, thighs, and buttocks), yielding lower WHR values around 0.8 or below and a protective peripheral distribution that accounts for women's overall higher body fat percentage—averaging 25-31% in adults versus 18-24% in men. These dimorphic patterns emerge subtly before puberty but intensify post-puberty, persisting into adulthood unless altered by conditions like menopause.[34][47][48]| Pattern | Primary Locations | Typical WHR | Predominant Sex |

|---|---|---|---|

| Android | Abdominal visceral and trunk subcutaneous | >0.9 | Male |

| Gynoid | Gluteofemoral subcutaneous (hips, thighs) | <0.8 | Female |

Muscular Composition and Tissues

Skeletal muscle constitutes 30-40% of total body mass in humans and represents the primary muscular tissue influencing body shape through its volume, distribution, and contractile properties.[50][51] This tissue, comprising 50-75% of total body protein, attaches to the skeleton via tendons, providing structural support and enabling posture that defines bodily contours.[51] Unlike smooth or cardiac muscle, skeletal muscle's striated fibers allow voluntary control and visible bulk, directly impacting perceived body form such as limb girth and torso width.[50] At the cellular level, skeletal muscle fibers are multinucleated cells packed with myofibrils, consisting of sarcomeres formed by actin and myosin filaments responsible for contraction.[52] Fibers classify into type I (slow-twitch, oxidative, fatigue-resistant) and type II (fast-twitch, glycolytic, power-oriented, with IIA oxidative-glycolytic and IIX purely glycolytic subtypes).[53] Proportions vary by muscle group and individual genetics; for instance, postural muscles like the soleus favor type I fibers (up to 80%), while prime movers like the gastrocnemius blend types more evenly.[53] This heterogeneity influences hypertrophy potential and aesthetic shape, with higher type II dominance linked to greater muscle definition under training.[54] Sex dimorphism in muscular composition markedly affects body shape: males average 36% more total skeletal muscle mass than females, with upper-body muscles (e.g., pectorals, deltoids) showing even larger disparities due to androgen-driven fiber hypertrophy.[55][56] Females exhibit relatively higher type I fiber reliance in certain muscles, but overall fiber type distributions remain similar across sexes, with differences primarily in fiber size rather than proportion.[57][33] This results in males displaying broader, more angular silhouettes from enhanced upper-body mass, contrasting with females' proportionally greater lower-body muscle relative to total lean mass.[58][55] Individual variations in muscle tissue quality, including satellite cell density and extracellular matrix composition, further modulate shape adaptability to exercise or disuse, though baseline genetics set fiber endowments largely unalterable.[33] Atrophy or hypertrophy alters contours, but core composition—dominated by protein-rich myofibrils—underpins stable body architecture across populations.[52]Reproductive and Secondary Sexual Features

The female pelvis displays pronounced sexual dimorphism adapted for reproduction, featuring a wider transverse diameter of the inlet (averaging 12-13 cm compared to 11 cm in males), a shallower anteroposterior dimension, and a larger subpubic angle (typically 80-100 degrees versus 50-60 degrees in males), which collectively broaden the bi-iliac breadth and contribute to the hourglass silhouette characteristic of female body shape.[43][59] These features facilitate the passage of the fetal head during childbirth while balancing bipedal locomotion demands.[60] In contrast, the male pelvis is narrower, deeper, and more conical, with thicker bones optimized for transmitting upper body weight to the lower limbs, resulting in reduced hip width relative to shoulder breadth.[43] Secondary sexual characteristics, arising post-puberty under gonadal hormone influence, further delineate body shape dimorphism. In females, mammary gland development leads to breast protrusion, increasing thoracic circumference and enhancing the waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) by accentuating lower body fat deposition in gluteofemoral regions, a pattern linked to estrogen-mediated fat storage that signals reproductive maturity.[2][35] This gynoid distribution contrasts with the android pattern in males, where testosterone promotes visceral and upper body fat alongside greater lean mass, minimizing waist expansion relative to hips.[2][35] Reproductive organs themselves exert minimal direct influence on external proportions beyond pelvic architecture, as ovaries and uterus remain internal in females, while testes in males contribute negligibly to silhouette due to scrotal positioning.[61] However, associated secondary traits like female labial development or male penile size do not substantially alter overall body shape metrics such as somatotypes or segmental proportions.[35] These features underscore causal linkages between reproductive fitness imperatives and morphological adaptations, with empirical data from geometric morphometrics confirming greater pelvic shape variance in females tied to obstetric constraints.[62][59]Developmental Dynamics

Prenatal and Childhood Formation

Human fetal body shape begins forming early in gestation through the interplay of genetic programming and in utero environmental factors, with skeletal structures emerging from mesenchymal condensations around weeks 6-8, establishing foundational proportions such as limb-to-torso ratios.[63] Prenatal sex differences in morphology arise primarily from gonadal hormone exposure; testosterone in male fetuses, peaking between weeks 8-24, promotes greater skeletal robusticity, longer limb bones, and denser muscle fiber development, while female fetuses exhibit relatively wider pelvic basins and earlier fat deposition patterns influenced by estrogen.[4] [64] Fetal fat accumulation is negligible until approximately 24 weeks, comprising about 6% of body weight in a 2.4-kg fetus and rising to 14% by term, concentrated initially in subcutaneous depots over the trunk and limbs, setting trajectories for later distribution.[65] Maternal nutrition and metabolic status exert epigenetic influences on fetal body composition; for instance, maternal obesity or overnutrition can alter DNA methylation in metabolic genes, leading to increased fetal adiposity and preferential visceral fat programming, as evidenced by cord blood epigenomic profiles correlating with neonatal fat mass.[66] [67] Low prenatal nutrient availability, conversely, is linked to reduced fetal lean mass and reprogrammed fat partitioning, with low birth weight infants showing lifelong shifts toward central adiposity and diminished muscle mass.[68] These prenatal dynamics establish baseline somatotypes, with twin studies indicating heritability of up to 80% for skeletal frame and fat patterning, modulated by placental hormone transfer.[69] In childhood, from birth through pre-puberty (ages 0-10), body shape evolves via rapid linear growth spurts driven by growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-1, with average height velocity peaking at 25 cm/year in infancy and stabilizing at 5-7 cm/year by age 5, influencing overall proportions.[70] Body fat percentage, highest at birth (around 14-16% in males, 16-18% in females), surges to 25-30% by 6 months due to nutritional intake, then declines to 14% in boys and 19% in girls by age 6, reflecting sex-specific lean mass accrual where boys develop relatively more appendicular muscle.[71] [72] Environmental factors, particularly postnatal nutrition, critically shape these patterns; adequate protein and energy intake supports skeletal width and muscle hypertrophy, while caloric excess promotes disproportionate fat gain, altering waist-to-hip ratios independently of genetics.[73] Physical activity in early childhood further refines muscular composition, enhancing bone density and limb girth, with epidemiological data showing that suboptimal environments (e.g., undernutrition) result in stunted trunk growth and persistent thin-fat phenotypes.[74][75]Pubertal Transformations

Puberty triggers substantial alterations in body shape via surges in sex steroids, growth hormone, and insulin-like growth factor-1, culminating in pronounced sexual dimorphism. These changes encompass shifts in skeletal proportions, body composition, and fat distribution patterns, with peak bone accretion occurring during this phase. In both sexes, a growth spurt precedes gonadal maturation, but females experience it earlier (typically ages 10-14) and males later (ages 12-16), contributing to average adult height differences where males exceed females by approximately 13 cm on average.[76][77] In females, estrogen drives pelvic widening through increased subchondral bone deposition at the iliac crests and greater sciatic notches, elevating hip circumference and lowering the waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) to around 0.8 in adulthood. Concurrently, estradiol facilitates gynoid fat deposition, with females accruing significantly more total fat mass—often doubling prepubertal levels—predominantly in the hips, thighs, and breasts, enhancing curvaceous morphology. Lean mass increases modestly, but skeletal mass gains are less than in males, aligning with estrogen's role in epiphyseal closure and moderated linear growth.[78][77][76] In males, testosterone promotes androgenic skeletal remodeling, including clavicular lengthening and scapular broadening, which expand shoulder width relative to hips, yielding a V-shaped torso and WHR near 0.9. Males gain greater fat-free mass (up to 50% increase) and skeletal mass during puberty, with enhanced muscle hypertrophy in the upper body and core, while fat accumulation remains minimal and more centrally distributed in an android pattern. These transformations, regulated by higher androgen levels, establish greater overall lean tissue and bone density compared to females.[77][76]Aging and Senescence Effects

Aging is associated with progressive alterations in body shape, primarily driven by declines in skeletal integrity, muscle mass, and shifts in adipose tissue distribution. After age 30, individuals experience a gradual loss of lean tissue, including skeletal muscle (sarcopenia), which reduces overall body mass and contributes to a less toned, more diminutive silhouette; this process accelerates after age 60, with annual muscle loss rates of 1-2% in both sexes.[79] Concurrently, body fat mass increases, particularly in central depots such as the abdomen, leading to a more android-like distribution regardless of baseline morphology, as evidenced by 3D body scanning studies of over 3,000 adults showing consistent inward reshaping of the torso with age.[80] These changes reflect underlying cellular senescence, hormonal declines, and reduced metabolic efficiency, rather than mere caloric imbalance.[81] Skeletal senescence manifests as height reduction, averaging 1-2 cm per decade after age 50, due to intervertebral disc dehydration and compression, vertebral microfractures from osteoporosis, and kyphotic posture from weakened paraspinal muscles.[82] In women, postmenopausal estrogen deficiency exacerbates bone resorption, amplifying spinal curvature and forward stoop, while men experience similar but less pronounced effects from androgen decline.[83] This results in a shortened, more stooped frame that alters proportions, with the center of gravity shifting anteriorly and increasing fall risk.[84] Adipose redistribution favors visceral accumulation over subcutaneous stores, elevating waist-to-hip ratios and promoting a protuberant abdomen; cross-sectional data indicate this shift begins in midlife and peaks around age 65-70 before potential late-life fat decline.[85] In females, the menopausal transition independently drives this pattern, with estrogen loss prompting a 5-10% increase in intra-abdominal fat within 5 years post-cessation, transitioning from gluteofemoral to android dominance and heightening metabolic risks independent of total fat mass.[86][87] Males undergo analogous centralization via testosterone reduction, compounded by sarcopenic obesity—where muscle atrophy coincides with fat infiltration into remaining lean tissue—further distorting limb and trunk contours.[88] Longitudinal cohorts confirm these dynamics persist across ethnicities, underscoring endocrine and inflammatory mechanisms over lifestyle alone.[89]Health Implications

Metabolic and Cardiovascular Risks

Body shape, particularly the distribution of adipose tissue between visceral (central, android) and subcutaneous (peripheral, gynoid) regions, significantly influences metabolic and cardiovascular risks independent of overall body mass index (BMI).[90] Android fat accumulation, characterized by excess intra-abdominal visceral fat, correlates with elevated risks of insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and metabolic syndrome, as visceral adipocytes release free fatty acids and pro-inflammatory cytokines directly into the portal vein, impairing hepatic insulin sensitivity and lipid metabolism.[91] In contrast, gynoid fat deposition in gluteal-femoral areas exhibits protective effects, with higher subcutaneous fat in these regions associated with lower incidence of type 2 diabetes and reduced systemic inflammation due to greater lipid storage capacity and adipokine profiles favoring insulin sensitivity.[92] Prospective cohort studies demonstrate that central obesity, often quantified by waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) or android-to-gynoid fat ratio, outperforms BMI as a predictor of cardiovascular disease (CVD) events. For instance, a 1 cm increase in waist circumference elevates future CVD risk by approximately 2%, while a 0.01 unit increase in WHR raises it by 5%, reflecting the causal role of visceral fat in endothelial dysfunction and atherogenesis.[93] Meta-analyses confirm that elevated WHR is linked to a nearly twofold increased odds of myocardial infarction (pooled OR 1.98), with android fat patterns showing stronger associations with clustering of metabolic syndrome components than gynoid distributions, particularly in postmenopausal women where shifts toward android patterns amplify risks.[94][95] Epidemiological data further highlight sex-specific patterns: men typically exhibit android-dominant shapes predisposing to higher baseline CVD mortality, whereas premenopausal women benefit from estrogen-driven gynoid fat, though this protection wanes post-menopause with visceral fat accrual.[96] Unfavorable central fat distribution remains a stronger determinant of atherosclerotic CVD and all-cause mortality than total adiposity, as evidenced by imaging studies showing visceral adipose tissue independently predicting coronary events even in non-obese individuals.[97][98] These associations underscore the need for anthropometric measures like WHR in risk stratification, as BMI alone fails to capture fat topography's metabolic implications.[99]Reproductive and Endocrine Outcomes

Body fat distribution exerts significant influence on endocrine regulation and reproductive capacity, primarily through adipose tissue's role as an active endocrine organ that modulates sex steroid metabolism, insulin sensitivity, and gonadotropin signaling. Android (central/abdominal) fat accumulation, characterized by higher visceral adipose tissue, promotes insulin resistance and dysregulated hormone production, including elevated free testosterone in women and reduced total testosterone in men via aromatase-mediated conversion to estradiol.[1] In contrast, gynoid (gluteofemoral) subcutaneous fat stores exhibit protective effects, supporting estrogen-driven lipid storage and lower metabolic inflammation, which correlates with preserved ovarian function and spermatogenesis.[1] In women, a lower waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) approximating 0.7 is associated with optimal estradiol and testosterone balance during the fertile menstrual phase, facilitating regular ovulation and higher fecundity.[100] Android fat patterns, however, elevate risks of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), marked by hyperandrogenism, anovulation, and infertility; studies indicate that central obesity exacerbates insulin resistance in PCOS patients, reducing spontaneous pregnancy rates by impairing follicular development.[101] [102] Higher WHR independently predicts infertility odds, with NHANES data from 2017–2020 showing positive correlations after adjusting for age and BMI.[103] Parity influences body shape longitudinally, as multiparous women exhibit elevated WHR (e.g., from 0.79 in nulliparous to 0.88 after 10 children across seven non-industrial societies), reflecting post-pregnancy shifts in pelvic and abdominal morphology, yet pre-gravid low WHR remains a marker of lifetime reproductive success.[104] Endocrine disruptions from android dominance also accelerate menopausal transition via chronic hypercortisolemia and estrogen dysregulation, increasing risks of premature ovarian insufficiency.[1] In men, android fat distribution inversely correlates with serum testosterone levels, fostering secondary hypogonadism through visceral adipocyte aromatase activity that elevates estradiol and suppresses hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis function.[105] [106] This pattern heightens infertility risks via reduced spermatogenesis and erectile dysfunction, with testosterone therapy reversing visceral fat gains and improving insulin sensitivity in hypogonadal cohorts.[107] Longitudinal data confirm that abdominal obesity precedes and amplifies age-related testosterone decline, compounding fertility impairment in obese males.[108]Musculoskeletal and Functional Impacts

Sexual dimorphism in human body shape manifests in the musculoskeletal system through differences in skeletal proportions, muscle distribution, and bone density, influencing strength, power output, and injury susceptibility. Males typically exhibit a narrower pelvis, broader shoulders, and greater overall skeletal robustness, correlating with higher lean muscle mass—particularly in the upper body—and increased bone mineral density, which enhance force generation capabilities. Females, conversely, possess a wider pelvic girdle adapted for parturition, with relatively greater lower-body muscle relative to upper-body mass and lower average bone density, potentially conferring advantages in endurance but disadvantages in raw power.[33][109][58] These structural variances directly impact functional performance. Male shoulder girdle dimorphism, characterized by larger scapulae and clavicles, supports superior upper-body strength, with males demonstrating approximately 50-75% greater arm power and force in flexion and extension tasks compared to females of similar body size. This contributes to advantages in activities requiring throwing or lifting, rooted in evolutionary pressures for upper-limb prowess. In contrast, female pelvic morphology necessitates greater transverse hip rotation and obliquity during gait, resulting in increased pelvic list and energy expenditure for locomotion, alongside reduced vertical center-of-mass displacement for stability.[110][111][112] Injury risks diverge accordingly. Males' higher muscle mass and bone strength mitigate certain overload fractures but elevate traumatic injury rates, such as in contact sports, due to greater force magnitudes. Females face heightened vulnerability to non-contact injuries, including anterior cruciate ligament tears—up to fourfold higher incidence—and stress fractures, attributable to wider Q-angles from pelvic breadth, lower estrogen-modulated bone density, and biomechanical gait asymmetries. Postmenopausal bone loss exacerbates female osteoporosis risk, with pelvic shape influencing fracture patterns, while male skeletal advantages wane faster with age in upper-body metrics.[113][114][115]Evidence from Epidemiological Data

Epidemiological studies from large cohorts demonstrate that measures of body shape, particularly those capturing central adiposity such as waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), predict all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk more effectively than body mass index (BMI) alone. In a pooled analysis of over 300,000 participants across multiple prospective studies, WHR exhibited the strongest and most consistent association with mortality, independent of BMI, with higher WHR values correlating with elevated hazard ratios for death from CVD and other causes.[116] Similarly, a multicenter cohort of Korean adults found that WHR values outside the range of 0.85-0.90 were linked to increased all-cause and CVD mortality, highlighting an optimal distribution for survival.[117] Android (central) fat distribution, characterized by higher abdominal accumulation, confers greater health risks compared to gynoid (peripheral) patterns, as evidenced by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry data from population-based samples. A study of over 5,000 adults showed that android fat mass was positively associated with CVD risk factors like hypertension and dyslipidemia, whereas gynoid fat mass displayed inverse or neutral relationships after adjusting for total adiposity.[118] The android-to-gynoid fat ratio further amplifies this, predicting metabolic syndrome and CVD events in both normal-weight and obese individuals, with ratios above 1.0 indicating heightened vulnerability.[119] Sex-specific patterns emerge, with android dominance in males driving excess risk, while gynoid distribution in females may offer partial protection against age-related CVD progression.[120] Alternative shape indices, such as A Body Shape Index (ABSI), which integrates waist circumference, BMI, and height, outperform BMI in forecasting mortality across diverse populations. Meta-analyses confirm ABSI's superior association with CVD, diabetes, and all-cause death, with hazard ratios increasing linearly beyond population norms, even among non-obese individuals.[121] Body shape phenotypes derived from principal component analysis of anthropometrics also link distinct morphologies—such as truncal-dominant forms—to elevated cancer incidence, with 17 tumor types showing positive correlations in multinational cohorts exceeding 400,000 participants.[122] These findings underscore central fatness as a causal mediator of adverse outcomes, beyond mere total body weight, in longitudinal data spanning decades.[123]| Anthropometric Index | Key Association with Health Outcomes | Population Example |

|---|---|---|

| Waist-to-Hip Ratio (WHR) | Higher values (>0.90 men, >0.85 women) linked to 20-50% increased CVD mortality risk | Korean cohort, n>100,000[117] |

| Android/Gynoid Fat Ratio | Ratios >1.0 predict metabolic syndrome; gynoid protective | US adults via DXA, n=5,000+[118] |

| A Body Shape Index (ABSI) | Linear rise in all-cause mortality hazard per z-score increase | Global meta-analysis, multiple cohorts[121] |

Evolutionary Foundations

Sexual Selection Mechanisms

Sexual selection operates on human body shape primarily through intersexual choice, where mate preferences favor dimorphic traits signaling genetic quality, health, and reproductive potential, and intrasexual competition, particularly among males for dominance and resource control. In females, men across cultures rate silhouettes with a waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) of 0.7 as most attractive, a configuration linked to peak fertility, estrogen-mediated fat distribution in gluteofemoral regions supportive of lactation and fetal development, and reduced morbidity from conditions like cardiovascular disease.[10][125] This preference persists in ratings of both static figures and moving bodies, with neural imaging showing activation of reward centers for low-WHR forms, indicating an evolved mechanism for detecting cues of ovarian function and long-term pair-bond viability.[126] For males, female preferences target a high shoulder-to-waist ratio (SWR) around 1.6, emphasizing V-shaped torsos with broad shoulders and narrow waists, which correlate with upper body strength and testosterone-driven musculature.[127] Such somatotypes explain up to 80% of variance in bodily attractiveness judgments, serving as honest signals of fighting ability and provisioning capacity, shaped by ancestral selection pressures from male-male agonism and female choice for protective mates.[128] Electroencephalography studies confirm that higher SWR elicits enhanced neural processing of attractiveness and perceptual dominance, underscoring a biological basis beyond cultural learning.[129] Cross-cultural evidence, including samples from industrialized and hunter-gatherer societies, demonstrates invariance in these ideals despite nutritional or media differences, attributing consistency to universal adaptations rather than parochial norms; for instance, preferences for low female WHR hold in 18 populations from Africa, Europe, and Asia.[130][131] Intrasexual dynamics amplify these traits, as male body size and form predict competitive success, indirectly boosting reproductive access via winner-take-all hierarchies observed in ethnographic data.[132] While some variation exists—such as slightly higher preferred WHR in resource-scarce environments signaling energy reserves—the core dimorphic patterns align with Darwinian predictions of sexual selection favoring exaggerated, costly signals verifiable by empirical fitness correlates.[133]Natural Selection and Adaptive Traits

Natural selection has molded human body shape to optimize survival in varying environments, particularly through adaptations enhancing thermoregulation, locomotion efficiency, and resource utilization. In colder climates, selection favors larger body mass and more compact proportions to conserve metabolic heat, as larger volumes relative to surface area reduce radiative and convective losses.[134] This aligns with Bergmann's rule, observed across endothermic species including humans, where populations at higher latitudes exhibit greater average body size compared to those in tropical regions.[134] Complementarily, Allen's rule drives shorter distal limb lengths in cold-adapted groups to minimize exposed surface area prone to frostbite and heat dissipation, with genetic and developmental bases reinforcing these patterns.[135] Such traits likely conferred advantages in ancestral foraging and persistence hunting scenarios, where thermal stress directly impacted energy budgets and mortality rates. Quantitative analyses of skeletal metrics from diverse populations confirm directional selection's role, tempered by genetic drift and trait covariation. For example, radial length decreases from 265.6 mm in Ugandan samples to 226.2 mm in Arctic Inuit groups, paralleling latitudinal gradients and indicating climatic pressure on appendicular proportions.[136] Tibial and femoral lengths follow similar trends, though humerus elongation in some lineages suggests correlated responses to selection on overall limb integration rather than isolated thermoregulation.[136] These variations persist ontogenetically, with climate correlating to limb growth trajectories from infancy, supporting heritable adaptations via natural selection over phenotypic plasticity alone.[137] In hot climates, conversely, selection promotes slender builds and elongated limbs to facilitate convective cooling and sweat evaporation, aiding endurance activities critical for survival in arid or savanna habitats.[138] Locomotor demands further refined body shape under natural selection, prioritizing bipedal efficiency over quadrupedal ancestry. Early hominins like Australopithecus afarensis (circa 3-4 million years ago) evolved wide, flaring iliac blades in the pelvis to stabilize the trunk and extend stride length despite short legs, reducing energetic costs of upright travel by up to 75% compared to quadrupeds.[139] By Homo erectus (circa 1.8 million years ago), narrower pelvic breadths and repositioned gluteal muscles enhanced hip extension for long-distance walking, while limb proportions shifted toward relatively longer crural indices (tibia-to-femur ratio) for biomechanical leverage.[139] These changes, evident in fossil records, balanced selection for speed and stability against environmental hazards like predation, with modern human averages reflecting refined adaptations for persistence pursuits in open terrains.[139] Overall, body shape's adaptive architecture underscores selection's prioritization of functional resilience, distinct from drift-dominated neutral traits.[136]Empirical Support from Cross-Species and Cross-Cultural Studies

Sexual dimorphism in body shape is evident across primate species, where males often exhibit proportionally broader shoulders, narrower hips, and greater overall upper-body mass compared to females, adaptations linked to intrasexual competition and mate guarding. For instance, in gorillas and orangutans, extreme dimorphism results in males having robust torsos and elongated arms, contrasting with females' more compact builds, with ratios of male-to-female body mass reaching up to 2.5:1 in some taxa.[140] [141] These patterns extend to other mammals, such as artiodactyls and carnivores, where male-biased skeletal proportions facilitate agonistic behaviors, suggesting conserved evolutionary pressures shaping body morphology beyond humans.[142] In humans, cross-cultural investigations reinforce the universality of these dimorphic ideals, with preferences for female waist-to-hip ratios (WHR) around 0.7—indicative of gynoid fat distribution and reproductive health—observed consistently across diverse groups, including Europeans, Asians, Africans, and indigenous populations. A study involving participants from Iran, Norway, Poland, and Russia found men rating low-WHR female figures highest in attractiveness, even when controlling for body mass index, mirroring findings in hunter-gatherer societies like the Hadza.[143] [125] Similarly, male shoulder-to-hip ratios approximating 1.4 (V-shaped torso) elicit strong preferences in women from varied cultural contexts, from Western urbanites to non-industrialized groups, pointing to innate cues of strength and genetic quality rather than learned aesthetics.[144] [145] These convergent findings across species and societies challenge purely cultural explanations for body shape norms, as dimorphic traits persist despite environmental differences, likely reflecting selection for fertility signaling in females and competitive prowess in males. Empirical tests, such as Singh's replications in 18 nations, show minimal deviation in WHR optima (0.68–0.72), with deviations correlating to poorer health outcomes like reduced ovarian function, underscoring causal links to reproductive fitness.[146] [7] While some variation exists—e.g., slightly higher preferred body mass in resource-scarce cultures—the core proportional preferences align with cross-primate morphology, supporting an adaptive, pan-specific foundation.[147]Assessment and Classification

Anthropometric Measurements

Anthropometric measurements quantify body shape through standardized assessments of linear dimensions, circumferences, and derived indices, enabling classification of somatotypes such as android (central fat accumulation) versus gynoid (peripheral distribution). These metrics, rooted in noninvasive protocols developed by organizations like the World Health Organization (WHO) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), prioritize reproducibility via consistent landmarks and equipment, such as flexible but inelastic tapes applied horizontally with 100-150g tension.[148][149] Waist circumference (WC) and hip circumference (HC) form the core of shape evaluation, as they capture regional fat deposition patterns linked to metabolic variance between sexes and populations.[150] Waist circumference is measured at the midpoint between the inferior margin of the last palpable rib and the superior iliac crest, reflecting abdominal adiposity independent of overall size.[148] Hip circumference targets the maximal girth around the buttocks, typically over the greater trochanters, to gauge lower-body volume.[149] The waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), computed as WC divided by HC, serves as a primary index of shape, with values exceeding 0.90 in men or 0.85 in women signaling elevated cardiometabolic risk due to visceral fat preponderance.[148][151] Complementary indices include the waist-to-height ratio (WHtR), where WC divided by standing height below 0.5 approximates low-risk profiles across ages and ethnicities, outperforming BMI in shape-specific predictions.[152]| Index | Formula | Interpretation for Shape |

|---|---|---|

| Waist-to-Hip Ratio (WHR) | WC (cm) / HC (cm) | >0.90 (men), >0.85 (women): Android shape, central obesity risk |

| Waist-to-Height Ratio (WHtR) | WC (cm) / Height (cm) | <0.5: Favorable peripheral distribution; ≥0.5: Central accumulation |

| A Body Shape Index (ABSI) | WC (m) / [BMI^(2/3) × Height^(1/2) (m)] | Independent of BMI; higher values correlate with mortality beyond adiposity alone |

Somatotype Typologies

The somatotype typology, developed by American psychologist William H. Sheldon in the 1940s, categorizes human physique along three germ-layer-derived components: ectomorphy (linearity and slenderness derived from the ectoderm), mesomorphy (muscularity and robustness from the mesoderm), and endomorphy (roundness and relative adiposity from the endoderm).[155] Sheldon rated each component on a 7-point scale, with extremes representing dominant pure types—ectomorphs as tall, thin, and fragile; mesomorphs as rectangular, hard, and athletically proportioned; and endomorphs as soft, rounded, and stocky—while most individuals exhibit blends.[156] This system drew from photographic analysis of thousands of male college students, aiming to quantify constitutional morphology.[156] Sheldon's original framework extended to constitutional psychology, correlating somatotypes with temperament—ectomorphs as introverted and cerebral, mesomorphs as assertive and dominant, endomorphs as viscerotonic and sociable—but these behavioral linkages lack empirical support and are widely rejected as unsubstantiated.[157] Physical somatotyping has faced criticism for oversimplification, as body composition varies with age, nutrition, exercise, and environment rather than fixed genetic archetypes; longitudinal studies show shifts, such as increased endomorphy with sedentary lifestyles or mesomorphy through resistance training.[158] Despite this, somatotypes retain descriptive utility in anthropometry, with heritability estimates for components ranging from 0.4 to 0.7 based on twin studies, indicating partial genetic influence modulated by lifestyle factors.[159] Refinements like the Heath-Carter anthropometric method, introduced in 1967, operationalize somatotyping without relying on subjective photography, using 10 measurements including skinfold thicknesses (for endomorphy), limb girths and bone breadths (for mesomorphy), and height-to-weight ratios (for ectomorphy) via standardized equations.[160] Endomorphy is calculated as the sum of triceps, subscapular, and supraspinale skinfolds multiplied by 170.18 and divided by height in cm; mesomorphy derives from corrected arm and calf girths plus bi-epicondylar breadths; ectomorphy from ponderal index adjustments if height-weight ratios fall within specific thresholds.[161] This method yields a three-numeral rating (e.g., 2-5-3 for balanced endomorph-mesomorph dominance), plotted on a somatochart for visualization, and demonstrates high inter-rater reliability (r > 0.9) in trained assessors.[162] In applied contexts, such as sports science, Heath-Carter somatotypes profile athletes empirically: elite powerlifters average 2.5-6.5-1.5 (high mesomorphy), endurance runners 1.5-2.5-4.0 (ectomorphic dominance), and sumo wrestlers 7.0-4.0-1.0 (endomorphic-mesomorphic).[159] Cross-sectional data from over 20,000 athletes across 50 sports confirm associations between somatotype and performance demands, with mesomorphy correlating positively with strength metrics (r = 0.45-0.60) and ectomorphy with aerobic efficiency, though causation is bidirectional due to training selection effects.[159] Recent bioimpedance adaptations integrate electrical impedance for non-invasive estimates, correlating strongly (r = 0.82-0.95) with anthropometric gold standards, enhancing scalability for population studies.[163] Nonetheless, somatotypes do not predict individual outcomes deterministically, as randomized intervention trials demonstrate modifiable components; for instance, 12-week resistance programs increase mesomorphy ratings by 0.5-1.0 units on average.[164]| Somatotype Component | Primary Characteristics | Key Anthropometric Indicators (Heath-Carter) | Example Correlations in Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ectomorphy | Linear frame, low fat/muscle mass, high surface-to-volume ratio | Height ÷ cube root of weight > 40.75; low girths | Positive with VO2 max in distance events (r = 0.35)[159] |

| Mesomorphy | Muscular development, broad shoulders, strong skeletal frame | Upper arm/calf girths corrected for skinfold; bi-iliac/bimalleolar breadths | Strong with vertical jump/1RM strength (r = 0.50-0.70)[164] |

| Endomorphy | Relative adiposity, rounded contours, shorter limbs | Sum of skinfolds (triceps + subscapular + supraspinale) × 170.18 ÷ height | Inverse with metabolic rate; higher in weight-class sports like wrestling[155] |