Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hyperthyroidism

View on Wikipedia

| Hyperthyroidism | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Overactive thyroid, hyperthyreosis |

| |

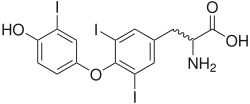

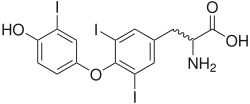

| Triiodothyronine (T3, pictured) and thyroxine (T4) are both forms of thyroid hormone. | |

| Specialty | Endocrinology |

| Symptoms | Irritability, muscle weakness, sleeping problems, fast heartbeat, heat intolerance, diarrhea, enlargement of the thyroid, weight loss[1] |

| Complications | Thyroid storm[2] |

| Usual onset | 20–50 years old[2] |

| Causes | Graves' disease, multinodular goiter, toxic adenoma, inflammation of the thyroid, eating too much iodine, too much synthetic thyroid hormone[1][2] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms and confirmed by blood tests[1] |

| Treatment | Radioiodine therapy, medications, thyroid surgery[1] |

| Medication | Beta blockers, methimazole[1] |

| Frequency | 1.2% (US)[3] |

| Deaths | Rare directly, unless thyroid storm occurs; associated with increased mortality if untreated (1.23 HR)[4] |

Hyperthyroidism is a endocrine disease in which the thyroid gland produces excessive amounts of thyroid hormones.[3] Thyrotoxicosis is a condition that occurs due to elevated levels of thyroid hormones of any cause and therefore includes hyperthyroidism.[3] Some, however, use the terms interchangeably.[5] Signs and symptoms vary between people and may include irritability, muscle weakness, sleeping problems, a fast heartbeat, heat intolerance, diarrhea, enlargement of the thyroid, hand tremor, and weight loss.[1] Symptoms are typically less severe in the elderly and during pregnancy.[1] An uncommon but life-threatening complication is thyroid storm in which an event such as an infection results in worsening symptoms such as confusion and a high temperature; this often results in death.[2] The opposite is hypothyroidism, when the thyroid gland does not make enough thyroid hormone.[6]

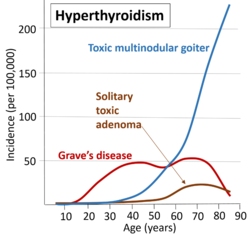

Graves' disease is the cause of about 50% to 80% of the cases of hyperthyroidism in the United States.[1][7] Other causes include multinodular goiter, toxic adenoma, inflammation of the thyroid, eating too much iodine, and too much synthetic thyroid hormone.[1][2] A less common cause is a pituitary adenoma.[1] The diagnosis may be suspected based on signs and symptoms and then confirmed with blood tests.[1] Typically blood tests show a low thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) and raised T3 or T4.[1] Radioiodine uptake by the thyroid, thyroid scan, and measurement of antithyroid autoantibodies (thyroidal thyrotropin receptor antibodies are positive in Graves' disease) may help determine the cause.[1]

Treatment depends partly on the cause and severity of the disease.[1] There are three main treatment options: radioiodine therapy, medications, and thyroid surgery.[1] Radioiodine therapy involves taking iodine-131 by mouth, which is then concentrated in and destroys the thyroid over weeks to months.[1] The resulting hypothyroidism is treated with synthetic thyroid hormone.[1] Medications such as beta blockers may control the symptoms, and anti-thyroid medications such as methimazole may temporarily help people while other treatments are having an effect.[1] Surgery to remove the thyroid is another option.[1] This may be used in those with very large thyroids or when cancer is a concern.[1] In the United States, hyperthyroidism affects about 1.2% of the population.[3] Worldwide, hyperthyroidism affects 2.5% of adults.[8] It occurs between two and ten times more often in women.[1] Onset is commonly between 20 and 50 years of age.[2] Overall, the disease is more common in those over the age of 60 years.[1]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Hyperthyroidism may be asymptomatic or present with significant symptoms.[2] Some of the symptoms of hyperthyroidism include nervousness, irritability, increased perspiration, heart racing, hand tremors, anxiety, trouble sleeping, thinning of the skin, fine brittle hair, and muscular weakness—especially in the upper arms and thighs. More frequent bowel movements may occur, and diarrhea is common. Weight loss, sometimes significant, may occur despite a good appetite (though 10% of people with a hyperactive thyroid experience weight gain), vomiting may occur, and, for women, menstrual flow may lighten and menstrual periods may occur less often, or with longer cycles than usual.[9][10]

The thyroid hormone is critical to the normal function of cells. In excess, it both overstimulates metabolism and disrupts the normal functioning of sympathetic nervous system, causing speeding up of various body systems and symptoms resembling an overdose of epinephrine (adrenaline). These include fast heartbeat and symptoms of palpitations, nervous system tremor such as of the hands and anxiety symptoms, digestive system hypermotility, unintended weight loss, and, in lipid panel blood tests, a lower and sometimes unusually low serum cholesterol.[11]

Major clinical signs of hyperthyroidism include weight loss (often accompanied by an increased appetite), anxiety, heat intolerance, hair loss, muscle aches, weakness, fatigue, hyperactivity, irritability, high blood sugar,[11] excessive urination, excessive thirst, delirium, tremor, pretibial myxedema (in Graves' disease), emotional lability, and sweating. Panic attacks, inability to concentrate, and memory problems may also occur. Psychosis and paranoia, common during thyroid storm, are rare with milder hyperthyroidism. Many persons will experience complete remission of symptoms 1 to 2 months after a euthyroid state is obtained, with a marked reduction in anxiety, sense of exhaustion, irritability, and depression. Some individuals may have an increased rate of anxiety or persistence of affective and cognitive symptoms for several months to up to 10 years after a euthyroid state is established.[12] In addition, those with hyperthyroidism may present with a variety of physical symptoms such as palpitations and abnormal heart rhythms (the notable ones being atrial fibrillation), shortness of breath (dyspnea), loss of libido, amenorrhea, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, gynecomastia and feminization.[13] Long term untreated hyperthyroidism can lead to osteoporosis. These classical symptoms may not be present often in the elderly.[14]

Bone loss, which is associated with overt but not subclinical hyperthyroidism, may occur in 10 to 20% of patients. This may be due to an increase in bone remodelling and a decrease in bone density, which increases fracture risk. It is more common in postmenopausal women; less so in younger women and men. Bone disease related to hyperthyroidism was first described by Frederick von Recklinghausen, in 1891; he described the bones of a woman who died of hyperthyroidism as appearing "worm-eaten".[15]

Neurological manifestations can include tremors, chorea, myopathy, and in some susceptible individuals (in particular of Asian descent) periodic paralysis. An association between thyroid disease and myasthenia gravis has been recognized. Thyroid disease, in this condition, is autoimmune in nature, and approximately 5% of people with myasthenia gravis also have hyperthyroidism. Myasthenia gravis rarely improves after thyroid treatment and the relationship between the two entities is becoming better understood over the past 15 years.[16][17][18]

In Graves' disease, ophthalmopathy may cause the eyes to look enlarged because the eye muscles swell and push the eye forward. Sometimes, one or both eyes may bulge. Some have swelling of the front of the neck from an enlarged thyroid gland (a goiter).[19]

Minor ocular (eye) signs, which may be present in any type of hyperthyroidism, are eyelid retraction ("stare"), extraocular muscle weakness, and lid-lag.[20] In hyperthyroid stare (Dalrymple sign) the eyelids are retracted upward more than normal (the normal position is at the superior corneoscleral limbus, where the "white" of the eye begins at the upper border of the iris). Extraocular muscle weakness may present with double vision. In lid-lag (von Graefe's sign), when the person tracks an object downward with their eyes, the eyelid fails to follow the downward-moving iris, and the same type of upper globe exposure which is seen with lid retraction occurs, temporarily. These signs disappear with treatment of the hyperthyroidism.[citation needed]

Neither of these ocular signs should be confused with exophthalmos (protrusion of the eyeball), which occurs specifically and uniquely in hyperthyroidism caused by Graves' disease (note that not all exophthalmos is caused by Graves' disease, but when present with hyperthyroidism is diagnostic of Graves' disease). This forward protrusion of the eyes is due to immune-mediated inflammation in the retro-orbital (eye socket) fat. Exophthalmos, when present, may exacerbate hyperthyroid lid-lag and stare.[21]

Thyroid storm

[edit]Thyroid storm is a severe form of thyrotoxicosis characterized by rapid and often irregular heartbeat, high temperature, vomiting, diarrhea, and mental agitation. Symptoms may not be typical in the young, old, or pregnant.[2] It usually occurs due to untreated hyperthyroidism and can be provoked by infections.[2] It is a medical emergency and requires hospital care to control the symptoms rapidly. The mortality rate in thyroid storm is 3.6-17%, usually due to multi-organ system failure.[8]

Hypothyroidism

[edit]Hyperthyroidism due to certain types of thyroiditis can eventually lead to hypothyroidism (a lack of thyroid hormone), as the thyroid gland is damaged. Also, radioiodine treatment of Graves' disease often eventually leads to hypothyroidism. Such hypothyroidism may be diagnosed with thyroid hormone testing and treated by oral thyroid hormone supplementation.[22]

Causes

[edit]

There are several causes of hyperthyroidism. Most often, the entire gland is overproducing thyroid hormone. Less commonly, a single nodule is responsible for the excess hormone secretion, called a "hot" nodule. Thyroiditis (inflammation of the thyroid) can also cause hyperthyroidism.[24] Functional thyroid tissue producing an excess of thyroid hormone occurs in a number of clinical conditions.

The major causes in humans are:

- Graves' disease. An autoimmune disease (usually, the most common cause with 50–80% worldwide, although this varies substantially with location- i.e., 47% in Switzerland (Horst et al., 1987) to 90% in the USA (Hamburger et al. 1981)). Thought to be due to varying levels of iodine in the diet.[25] It is eight times more common in females than males and often occurs in young females, around 20 to 40 years of age.[26]

- Toxic thyroid adenoma (the most common cause in Switzerland, 53%, thought to be atypical due to a low level of dietary iodine in this country)[25]

- Toxic multinodular goiter[citation needed]

High blood levels of thyroid hormones (most accurately termed hyperthyroxinemia) can occur for several other reasons:

- Inflammation of the thyroid is called thyroiditis. There are several different kinds of thyroiditis, including Hashimoto's thyroiditis (Hypothyroidism immune-mediated), and subacute thyroiditis (de Quervain's). These may be initially associated with secretion of excess thyroid hormone but usually progress to gland dysfunction and, thus, to hormone deficiency and hypothyroidism.

- Oral consumption of excess thyroid hormone tablets is possible (surreptitious use of thyroid hormone), as is the rare event of eating ground beef or pork contaminated with thyroid tissue, and thus thyroid hormones (termed hamburger thyrotoxicosis or alimentary thyrotoxicosis).[27] Pharmacy compounding errors may also be a cause.[28]

- Amiodarone, an antiarrhythmic drug, is structurally similar to thyroxine and may cause either under-or overactivity of the thyroid.[citation needed]

- Postpartum thyroiditis (PPT) occurs in about 7% of women during the year after they give birth. PPT typically has several phases, the first of which is hyperthyroidism. This form of hyperthyroidism usually corrects itself within weeks or months without the need for treatment.

- A struma ovarii is a rare form of monodermal teratoma that contains mostly thyroid tissue, which leads to hyperthyroidism.

- Excess iodine consumption, notably from algae such as kelp.

Thyrotoxicosis can also occur after taking too much thyroid hormone in the form of supplements, such as levothyroxine (a phenomenon known as exogenous thyrotoxicosis, alimentary thyrotoxicosis, or occult factitial thyrotoxicosis).[29]

Hypersecretion of thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), which in turn is almost always caused by a pituitary adenoma, accounts for much less than 1 percent of hyperthyroidism cases.[30]

Diagnosis

[edit]Measuring the level of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), produced by the pituitary gland (which in turn is also regulated by the hypothalamus's TSH-Releasing Hormone) in the blood, is typically the initial test for suspected hyperthyroidism. A low TSH level typically indicates that the pituitary gland is being inhibited or "instructed" by the brain to cut back on stimulating the thyroid gland, having sensed increased levels of T4 and/or T3 in the blood. In rare circumstances, a low TSH indicates primary failure of the pituitary, or temporary inhibition of the pituitary due to another illness (euthyroid sick syndrome) and so checking the T4 and T3 is still clinically useful.[11]

Measuring specific antibodies, such as anti-TSH-receptor antibodies in Graves' disease, or anti-thyroid peroxidase in Hashimoto's thyroiditis—a common cause of hypothyroidism—may also contribute to the diagnosis. The diagnosis of hyperthyroidism is confirmed by blood tests that show a decreased thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level and elevated T4 and T3 levels. TSH is a hormone made by the pituitary gland in the brain that tells the thyroid gland how much hormone to make. When there is too much thyroid hormone, the TSH will be low. A radioactive iodine uptake test and thyroid scan together characterize or enable radiologists and doctors to determine the cause of hyperthyroidism. The uptake test uses radioactive iodine injected or taken orally on an empty stomach to measure the amount of iodine absorbed by the thyroid gland. People with hyperthyroidism absorb much more iodine than healthy people, including radioactive iodine, which is easy to measure. A thyroid scan producing images is typically conducted in connection with the uptake test to allow visual examination of the over-functioning gland.[11]

Thyroid scintigraphy is a useful test to characterize (distinguish between causes of) hyperthyroidism, and this entity from thyroiditis. This test procedure typically involves two tests performed in connection with each other: an iodine uptake test and a scan (imaging) with a gamma camera. The uptake test involves administering a dose of radioactive iodine (radioiodine), traditionally iodine-131 (131I), and more recently iodine-123 (123I). Iodine-123 may be the preferred radionuclide in some clinics due to its more favorable radiation dosimetry (i.e., less radiation dose to the person per unit administered radioactivity) and a gamma photon energy more amenable to imaging with the gamma camera. For the imaging scan, I-123 is considered an almost ideal isotope of iodine for imaging thyroid tissue and thyroid cancer metastasis.[31] Thyroid scintigraphy should not be performed in those who are pregnant, a thyroid ultrasound with color flow doppler may be obtained as an alternative in these circumstances.[8]

Typical administration involves a pill or liquid containing sodium iodide (NaI) taken orally, which contains a small amount of iodine-131, amounting to perhaps less than a grain of salt. A 2-hour fast of no food prior to and for 1 hour after ingesting the pill is required. This low dose of radioiodine is typically tolerated by individuals otherwise allergic to iodine (such as those unable to tolerate contrast mediums containing larger doses of iodine such as used in CT scan, intravenous pyelogram (IVP), and similar imaging diagnostic procedures). Excess radioiodine that does not get absorbed into the thyroid gland is eliminated by the body in urine. Some people with hyperthyroidism may experience a slight allergic reaction to the diagnostic radioiodine and may be given an antihistamine.[citation needed]

The person returns 24 hours later to have the level of radioiodine "uptake" (absorbed by the thyroid gland) measured by a device with a metal bar placed against the neck, which measures the radioactivity emitted from the thyroid. This test takes about 4 minutes while the uptake % (i.e., percentage) is accumulated (calculated) by the machine software. A scan is also performed, wherein images (typically a center, left, and right angle) are taken of the contrasted thyroid gland with a gamma camera; a radiologist will read and prepare a report indicating the uptake % and comments after examining the images. People with hyperthyroidism will typically "take up" higher-than-normal levels of radioiodine. Normal ranges for RAI uptake are from 10 to 30%.

In addition to testing the TSH levels, many doctors test for T3, Free T3, T4, and/or Free T4 for more detailed results. Free T4 is unbound to any protein in the blood. Adult limits for these hormones are: TSH (units): 0.45 – 4.50 uIU/mL; T4 Free/Direct (nanograms): 0.82 – 1.77 ng/dl; and T3 (nanograms): 71 – 180 ng/dl. Persons with hyperthyroidism can easily exhibit levels many times these upper limits for T4 and/or T3. See a complete table of normal range limits for thyroid function at the thyroid gland article.

In hyperthyroidism, CK-MB (Creatine kinase) is usually elevated.[32]

Subclinical

[edit]In overt primary hyperthyroidism, TSH levels are low, and T4 and T3 levels are high. Subclinical hyperthyroidism is a milder form of hyperthyroidism characterized by low or undetectable serum TSH level, but with a normal serum free thyroxine level.[33] Although the evidence for doing so is not definitive, treatment of elderly persons having subclinical hyperthyroidism could reduce the number of cases of atrial fibrillation.[34] There is also an increased risk of bone fractures (by 42%) in people with subclinical hyperthyroidism; there is insufficient evidence to say whether treatment with antithyroid medications would reduce that risk.[35]

A 2022 meta-analysis found subclinical hyperthyroidism to be associated with cardiovascular death.[36]

Screening

[edit]In those without symptoms who are not pregnant, there is little evidence for or against screening.[37]

Treatment

[edit]Antithyroid drugs

[edit]Thyrostatics (antithyroid drugs) are drugs that inhibit the production of thyroid hormones, such as carbimazole (used in the UK) and methimazole (used in the US, Germany, and Russia), and propylthiouracil. Thyrostatics are believed to work by inhibiting the iodination of thyroglobulin by thyroperoxidase and, thus, the formation of tetraiodothyronine (T4). Propylthiouracil also works outside the thyroid gland, preventing the conversion of (mostly inactive) T4 to the active form T3. Because thyroid tissue usually contains a substantial reserve of thyroid hormone, thyrostatics can take weeks to become effective, and the dose often needs to be carefully titrated over a period of months, with regular doctor visits and blood tests to monitor results.[11]

Beta-blockers

[edit]Many of the common symptoms of hyperthyroidism, such as palpitations, trembling, and anxiety, are mediated by increases in beta-adrenergic receptors on cell surfaces. Beta blockers, typically used to treat high blood pressure, are a class of drugs that offset this effect, reducing rapid pulse associated with the sensation of palpitations, and decreasing tremor and anxiety. Thus, a person with hyperthyroidism can often obtain immediate temporary relief until the hyperthyroidism can be characterized with the Radioiodine test noted above, and more permanent treatment takes place. Note that these drugs do not treat hyperthyroidism or any of its long-term effects if left untreated, but rather, they treat or reduce only symptoms of the condition.[38]

Some minimal effect on thyroid hormone production, however, also comes with propranolol, which has two roles in the treatment of hyperthyroidism, determined by the different isomers of propranolol. L-propranolol causes beta-blockade, thus treating the symptoms associated with hyperthyroidism, such as tremor, palpitations, anxiety, and heat intolerance. D-propranolol inhibits thyroxine deiodinase, thereby blocking the conversion of T4 to T3, providing some, though minimal, therapeutic effect. Other beta-blockers are used to treat only the symptoms associated with hyperthyroidism.[39] Propranolol in the UK, and metoprolol in the US, are most frequently used to augment treatment for people with hyperthyroid.[40]

Diet

[edit]People with autoimmune hyperthyroidism (such as in Graves' disease) should not eat foods high in iodine, such as edible seaweed and seafood.[1]

From a public health perspective, the general introduction of iodized salt in the United States in 1924 resulted in lower disease, goiters, as well as improving the lives of children whose mothers would not have eaten enough iodine during pregnancy, which would have lowered the IQs of their children.[41]

Surgery

[edit]Surgery (thyroidectomy to remove the whole thyroid or a part of it) is not extensively used because most common forms of hyperthyroidism are quite effectively treated by the radioactive iodine method, and because there is a risk of also removing the parathyroid glands, and of cutting the recurrent laryngeal nerve, making swallowing difficult, and even simply generalized staphylococcal infection as with any major surgery. Some people with Graves' may opt for surgical intervention. This includes those who cannot tolerate medicines for one reason or another, people who are allergic to iodine, or people who refuse radioiodine.[42]

A 2019 systematic review concluded that the available evidence shows no difference between visually identifying the nerve or utilizing intraoperative neuroimaging during surgery, when trying to prevent injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerve during thyroid surgery.[43]

If people have toxic nodules, treatments typically include either the removal or injection of the nodule with alcohol.[44]

Radioiodine

[edit]In iodine-131 (radioiodine) radioisotope therapy, which was first pioneered by Dr. Saul Hertz,[45] radioactive iodine-131 is given orally (either by pill or liquid) on a one-time basis, to severely restrict, or altogether destroy the function of a hyperactive thyroid gland. This isotope of radioactive iodine used for ablative treatment is more potent than diagnostic radioiodine (usually iodine-123 or a very low amount of iodine-131), which has a biological half-life from 8–13 hours. Iodine-131, which also emits beta particles that are far more damaging to tissues at short range, has a half-life of approximately 8 days. People not responding sufficiently to the first dose are sometimes given an additional radioiodine treatment, at a larger dose. Iodine-131 in this treatment is picked up by the active cells in the thyroid and destroys them, rendering the thyroid gland mostly or completely inactive.[46]

Since iodine is picked up more readily (though not exclusively) by thyroid cells, and (more importantly) is picked up even more readily by overactive thyroid cells, the destruction is local, and there are no widespread side effects with this therapy. Radioiodine ablation has been used for over 50 years, and the only major reasons for not using it are pregnancy and breastfeeding (breast tissue also picks up and concentrates iodine). Once the thyroid function is reduced, replacement hormone therapy (levothyroxine) taken orally each day replaces the thyroid hormone that is normally produced by the body.[47]

There is extensive experience, over many years, of the use of radioiodine in the treatment of thyroid overactivity, and this experience does not indicate any increased risk of thyroid cancer following treatment. However, a study from 2007 has reported an increased number of cancer cases after radioiodine treatment for hyperthyroidism.[46]

The principal advantage of radioiodine treatment for hyperthyroidism is that it tends to have a much higher success rate than medications. Depending on the dose of radioiodine chosen, and the disease under treatment (Graves' vs. toxic goiter, vs. hot nodule, etc.), the success rate in achieving definitive resolution of the hyperthyroidism may vary from 75 to 100%. A major expected side-effect of radioiodine in people with Graves' disease is the development of lifelong hypothyroidism, requiring daily treatment with thyroid hormone. On occasion, some people may require more than one radioactive treatment, depending on the type of disease present, the size of the thyroid, and the initial dose administered.[48]

People with Graves' disease manifesting moderate or severe Graves' ophthalmopathy are cautioned against radioactive iodine-131 treatment, since it has been shown to exacerbate existing thyroid eye disease. People with mild or no ophthalmic symptoms can mitigate their risk with a concurrent six-week course of prednisone. The mechanisms proposed for this side effect involve a TSH receptor common to both thyrocytes and retro-orbital tissue.[49]

As radioactive iodine treatment results in the destruction of thyroid tissue, there is often a transient period of several days to weeks when the symptoms of hyperthyroidism may worsen following radioactive iodine therapy. In general, this happens as a result of thyroid hormones being released into the blood following the radioactive iodine-mediated destruction of thyroid cells that contain thyroid hormone. In some people, treatment with medications such as beta blockers (propranolol, atenolol, etc.) may be useful during this period. Most people do not experience any difficulty after the radioactive iodine treatment, usually given as a small pill. On occasion, neck tenderness or a sore throat may become apparent after a few days, if moderate inflammation in the thyroid develops and produces discomfort in the neck or throat area. This is usually transient, and not associated with a fever, etc.[citation needed]

It is recommended that breastfeeding be stopped at least six weeks before radioactive iodine treatment and that it not be resumed, although it can be done in future pregnancies. It also shouldn't be done during pregnancy, and pregnancy should be put off until at least 6–12 months after treatment.[50][51]

A common outcome following radioiodine is a swing from hyperthyroidism to easily treatable hypothyroidism, which occurs in 78% of those treated for Graves' thyrotoxicosis and in 40% of those with toxic multinodular goiter or solitary toxic adenoma.[52] Use of higher doses of radioiodine reduces the number of cases of treatment failure, with a penalty for higher response to treatment consisting mostly of higher rates of eventual hypothyroidism, which requires hormone treatment for life.[53]

There is increased sensitivity to radioiodine therapy in thyroids appearing on ultrasound scans as more uniform (hypoechogenic), due to densely packed large cells, with 81% later becoming hypothyroid, compared to just 37% in those with more normal scan appearances (normoechogenic).[54]

Thyroid storm

[edit]Thyroid storm presents with extreme symptoms of hyperthyroidism. It is treated aggressively with resuscitation measures along with a combination of the above modalities including: intravenous beta blockers such as propranolol, followed by a thioamide such as methimazole, an iodinated radiocontrast agent or an iodine solution if the radiocontrast agent is not available, and an intravenous steroid such as hydrocortisone.[55] Propylthiouracil is the preferred thioamide in thyroid storm as it can prevent the conversion of T4 to the more active T3 in the peripheral tissues in addition to inhibiting thyroid hormone production.[8]

Alternative medicine

[edit]In countries such as China, herbs used alone or with antithyroid medications are used to treat hyperthyroidism.[56] Very low quality evidence suggests that traditional Chinese herbal medications may be beneficial when taken along with routine hyperthyroid medications, however, there is no reliable evidence to determine the effectiveness of Chinese herbal medications for treating hyperthyroidism.[56]

Epidemiology

[edit]In the United States, hyperthyroidism affects about 1.2% of the population.[3] About half of these cases have obvious symptoms, while the other half do not.[2] It occurs between two and ten times more often in women.[1] The disease is more common in those over the age of 60 years.[1]

Subclinical hyperthyroidism modestly increases the risk of cognitive impairment and dementia.[57]

History

[edit]Caleb Hillier Parry first made the association between the goiter and eye protrusion in 1786; however, he did not publish his findings until 1825.[58] In 1835, Irish doctor Robert James Graves discovered a link between the protrusion of the eyes and goiter, giving his name to the autoimmune disease now known as Graves' Disease.[citation needed]

Pregnancy

[edit]Recognizing and evaluating hyperthyroidism in pregnancy is a diagnostic challenge.[59] Thyroid hormones are commonly elevated during the first trimester of pregnancy as the pregnancy hormone human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) stimulates thyroid hormone production, in a condition known as gestational transient thyrotoxicosis.[8] Gestational transient thyrotoxicosis generally abates in the second trimester as hCG levels decline and thyroid function normalizes.[8] Hyperthyroidism can increase the risk of complications for mother and child.[60] Such risks include pregnancy-related hypertension, pregnancy loss, low-birth weight, pre-eclampsia, preterm delivery, still birth and behavioral disorders later in the child's life.[8][61][60][62] Nonetheless, high maternal FT4 levels during pregnancy have been associated with impaired brain developmental outcomes of the offspring and this was independent of hCG levels.[63]

Propylthiouracil is the preferred antithyroid medication in the 1st trimester of pregnancy as it is less teratogenic than methimazole.[8]

Other animals

[edit]Cats

[edit]Hyperthyroidism is one of the most common endocrine conditions affecting older domesticated housecats. In the United States, up to 10% of cats over ten years old have hyperthyroidism.[64] The disease has become significantly more common since the first reports of feline hyperthyroidism in the 1970s. The most common cause of hyperthyroidism in cats is the presence of benign tumors called adenomas. 98% of cases are caused by the presence of an adenoma,[65] but the reason these cats develop such tumors continues to be studied.

The most common presenting symptoms are: rapid weight loss, tachycardia (rapid heart rate), vomiting, diarrhea, increased consumption of fluids (polydipsia), increased appetite (polyphagia), and increased urine production (polyuria). Other symptoms include hyperactivity, possible aggression, an unkempt appearance, and large, thick claws. Heart murmurs and a gallop rhythm can develop due to secondary hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. About 70% of affected cats also have enlarged thyroid glands (goiter). 10% of cats exhibit "apathetic hyperthyroidism", which is characterized by anorexia and lethargy.[66]

The same three treatments used with humans are also options in treating feline hyperthyroidism (surgery, radioiodine treatment, and anti-thyroid drugs). There is also a special low iodine diet available that will control the symptoms, providing no other food is fed; Hill's y/d formula, when given exclusively, decreases T4 production by limiting the amount of iodine needed for thyroid hormone production. It is the only available commercial diet that focuses on managing feline hyperthyroidism. Medical and dietary management using methimazole and Hill's y/d cat food will give hyperthyroid cats an average of 2 years before dying due to secondary conditions such as heart and kidney failure.[66] Drugs used to help manage the symptoms of hyperthyroidism are methimazole and carbimazole. Drug therapy is the least expensive option, even though the drug must be administered daily for the remainder of the cat's life. Carbimazole is only available as a once-daily tablet. Methimazole is available as an oral solution, a tablet, and compounded as a topical gel that is applied using a finger cot to the hairless skin inside a cat's ear. Many cat owners find this gel a good option for cats that don't like being given pills.[citation needed]

Radioiodine treatment, however, is not available in all areas, as this treatment requires nuclear radiological expertise and facilities that not only board the cat, but are specially equipped to manage the cat's urine, sweat, saliva, and stool, which are radioactive for several days after the treatment, usually for a total of 3 weeks (the cat spends the first week in total isolation and the next two weeks in close confinement).[67] In the United States, the guidelines for radiation levels vary from state to state; some states such as Massachusetts allow hospitalization for as little as two days before the animal is sent home with care instructions.[citation needed]

Dogs

[edit]Hyperthyroidism is much less common in dogs compared to cats.[68] Hyperthyroidism may be caused by a thyroid tumor. This may be a thyroid carcinoma. About 90% of carcinomas are very aggressive; they invade the surrounding tissues and metastasize (spread) to other tissues, particularly the lungs. This has a poor prognosis. Surgery to remove the tumor is often very difficult due to metastasis into arteries, the esophagus, or the windpipe. It may be possible to reduce the size of the tumor, thus relieving symptoms and allowing time for other treatments to work.[citation needed] About 10% of thyroid tumors are benign; these often cause few symptoms.[citation needed]

In dogs treated for hypothyroidism (lack of thyroid hormone), iatrogenic hyperthyroidism may occur as a result of an overdose of the thyroid hormone replacement medication, levothyroxine; in this case, treatment involves reducing the dose of levothyroxine.[69][70] Dogs which display coprophagy, the consumption of feces, and also live in a household with a dog receiving levothyroxine treatment, may develop hyperthyroidism if they frequently eat the feces from the dog receiving levothyroxine treatment.[71]

Hyperthyroidism may occur if a dog eats an excessive amount of thyroid gland tissue. This has occurred in dogs fed commercial dog food.[72]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y "Hyperthyroidism". www.niddk.nih.gov. July 2012. Archived from the original on 4 April 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Devereaux D, Tewelde SZ (May 2014). "Hyperthyroidism and thyrotoxicosis". Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America. 32 (2): 277–292. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2013.12.001. PMID 24766932.

- ^ a b c d e Bahn Chair RS, Burch HB, Cooper DS, Garber JR, Greenlee MC, Klein I, et al. (June 2011). "Hyperthyroidism and other causes of thyrotoxicosis: management guidelines of the American Thyroid Association and American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists". Thyroid. 21 (6): 593–646. doi:10.1089/thy.2010.0417. PMID 21510801.

- ^ Lillevang-Johansen M, Abrahamsen B, Jørgensen HL, Brix TH, Hegedüs L (28 March 2017). "Excess Mortality in Treated and Untreated Hyperthyroidism Is Related to Cumulative Periods of Low Serum TSH". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 102 (7). The Endocrine Society: 2301–2309. doi:10.1210/jc.2017-00166. ISSN 0021-972X. PMID 28368540. S2CID 3806882.

- ^ Schraga ED (30 May 2014). "Hyperthyroidism, Thyroid Storm, and Graves Disease". Medscape. Archived from the original on 5 April 2015. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ^ NIDDK (13 March 2013). "Hypothyroidism". Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ^ Brent GA (June 2008). "Clinical practice. Graves' disease". The New England Journal of Medicine. 358 (24): 2594–2605. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp0801880. PMID 18550875.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lee SY, Pearce EN (17 October 2023). "Hyperthyroidism: A Review". JAMA. 330 (15): 1472–1483. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.19052. PMC 10873132. PMID 37847271. S2CID 265937262.

- ^ Koutras DA (June 1997). "Disturbances of menstruation in thyroid disease". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 816 (1 Adolescent Gy): 280–284. Bibcode:1997NYASA.816..280K. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb52152.x. PMID 9238278. S2CID 5840966.

- ^ Shahid MA, Ashraf MA, Sharma S (January 2021). "Physiology, Thyroid Hormone". StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 29763182.

- ^ a b c d e "Thyrotoxicosis and Hyperthyroidism". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ "Depression and Psychosis in Neurological Practice.". Bradley's neurology in clinical practice (6th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders. 2012. pp. 102–103. ISBN 978-1-4377-0434-1.

- ^ Chan WB, Yeung VT, Chow CC, So WY, Cockram CS (April 1999). "Gynaecomastia as a presenting feature of thyrotoxicosis". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 75 (882): 229–231. doi:10.1136/pgmj.75.882.229. PMC 1741202. PMID 10715765.

- ^ "Hyperthyroidism - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 28 June 2024.

- ^ Miragaya J (31 July 2023). "Preventing 'Worm-eaten Bones' From Hyperthyroidism". Medscape.

- ^ Trabelsi L, Charfi N, Triki C, Mnif M, Rekik N, Mhiri C, et al. (June 2006). "[Myasthenia gravis and hyperthyroidism: two cases]". Annales d'Endocrinologie (in French). 67 (3): 265–9. doi:10.1016/s0003-4266(06)72597-5. PMID 16840920.

- ^ Song Rh, Yao Qm, Wang B, Li Q, Jia X, Zhang Ja (October 2019). "Thyroid disorders in patients with myasthenia gravis: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Autoimmunity Reviews. 18 (10). doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2019.102368. PMID 31404702. S2CID 199549144.

- ^ Zhu Y, Wang B, Hao Y, Zhu R (September 2023). "Clinical features of myasthenia gravis with neurological and systemic autoimmune diseases". Front Immunol. 14 (14:1223322). doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1223322. PMC 10538566. PMID 37781409.

- ^ "Hyperthyroidism". American Thyroid Association. Archived from the original on 5 March 2011. Retrieved 10 May 2010.

- ^ Mehtap C (2010). Differential diagnosis of hyperthyroidism. Nova Science Publishers. p. xii. ISBN 978-1-61668-242-2. OCLC 472720688.

- ^ Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry (2006). "Course-Based Physical Examination – Endocrinology – Endocrinology Objectives (Thyroid Exam)". Undergraduate Medical Education. University of Alberta. Archived from the original on 19 January 2008. Retrieved 28 January 2007.

- ^ "Hypothyroidism - Diagnosis and treatment - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Retrieved 6 May 2021.

- ^ Carlé A, Pedersen IB, Knudsen N, Perrild H, Ovesen L, Rasmussen LB, et al. (May 2011). "Epidemiology of subtypes of hyperthyroidism in Denmark: a population-based study". European Journal of Endocrinology. 164 (5): 801–809. doi:10.1530/EJE-10-1155. PMID 21357288. S2CID 25049060.

- ^ "Hyperthyroidism Overview". Archived from the original on 28 April 2010. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ^ a b Andersson M, Zimmermann MB (2010). "Influence of Iodine Deficiency and Excess on Thyroid Function Tests". Thyroid Function Testing. Endocrine Updates. Vol. 28. pp. 45–69. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-1485-9_3. ISBN 978-1-4419-1484-2. ISSN 1566-0729.

- ^ Services Do. "Thyroid - hyperthyroidism". www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 23 May 2025.

- ^ Parmar MS, Sturge C (September 2003). "Recurrent hamburger thyrotoxicosis". CMAJ. 169 (5): 415–417. PMC 183292. PMID 12952802.

- ^ Bains A, Brosseau AJ, Harrison D (2015). "Iatrogenic thyrotoxicosis secondary to compounded liothyronine". The Canadian Journal of Hospital Pharmacy. 68 (1): 57–9. doi:10.4212/cjhp.v68i1.1426. PMC 4350501. PMID 25762821.

- ^ Floyd JL (21 March 2017) [2009]. "Thyrotoxicosis". eMedicine. Archived from the original on 17 March 2010.

- ^ Weiss RE, Refetoff S. "Thyrotropin (TSH)-secreting pituitary adenomas". UpToDate. Archived from the original on 18 February 2011.

Last literature review version 19.1: January 2011. This topic last updated: 2 July 2009

- ^ Park HM (January 2002). "123I: almost a designer radioiodine for thyroid scanning". Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 43 (1): 77–78. PMID 11801707. Archived from the original on 12 October 2008. Retrieved 10 May 2010.

- ^ Mesko D, Pullmann R (December 2012). "Blood - Plasma - Serum". In Marks V, Cantor T, Mesko D, Pullmann R, Nosalova G (eds.). Differential diagnosis by laboratory medicine: a quick reference for physicians. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 156. ISBN 978-3-642-55600-5.

- ^ Biondi B, Cooper DS (February 2008). "The clinical significance of subclinical thyroid dysfunction". Endocrine Reviews. 29 (1): 76–131. doi:10.1210/er.2006-0043. PMID 17991805.

- ^ Surks MI, Ortiz E, Daniels GH, Sawin CT, Col NF, Cobin RH, et al. (January 2004). "Subclinical thyroid disease: scientific review and guidelines for diagnosis and management". JAMA. 291 (2): 228–238. doi:10.1001/jama.291.2.228. PMID 14722150.

- ^ Blum MR, Bauer DC, Collet TH, Fink HA, Cappola AR, da Costa BR, et al. (May 2015). "Subclinical thyroid dysfunction and fracture risk: a meta-analysis". JAMA. 313 (20): 2055–2065. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.5161. PMC 4729304. PMID 26010634.

- ^ Müller P, Leow MK, Dietrich JW (2022). "Minor perturbations of thyroid homeostasis and major cardiovascular endpoints-Physiological mechanisms and clinical evidence". Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine. 9 942971. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2022.942971. PMC 9420854. PMID 36046184.

- ^ LeFevre ML (May 2015). "Screening for thyroid dysfunction: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement". Annals of Internal Medicine. 162 (9): 641–650. doi:10.7326/m15-0483. PMID 25798805. S2CID 207538375.

- ^ "UpToDate". www.uptodate.com. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ^ Eber O, Buchinger W, Lindner W, Lind P, Rath M, Klima G, et al. (March 1990). "The effect of D- versus L-propranolol in the treatment of hyperthyroidism". Clinical Endocrinology. 32 (3): 363–372. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.1990.tb00877.x. PMID 2344697. S2CID 37948268.

- ^ Geffner DL, Hershman JM (July 1992). "Beta-adrenergic blockade for the treatment of hyperthyroidism". The American Journal of Medicine. 93 (1): 61–68. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(92)90681-Z. PMID 1352658.

- ^ Nisen M (22 July 2013). "How Adding Iodine To Salt Resulted in a Decade's Worth of IQ Gains for the United States". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 23 July 2013. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ^ Catania A, Guaitoli E, Carbotta G, Bianchini M, Di Matteo FM, Carbotta S, et al. (2012). "Total thyroidectomy for Graves' disease treatment". La Clinica Terapeutica. 164 (3): 193–196. doi:10.7417/CT.2013.1548. PMID 23868618.

- ^ Cirocchi R, Arezzo A, D'Andrea V, Abraha I, Popivanov GI, Avenia N, et al. (19 January 2019). Cochrane Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders Group (ed.). "Intraoperative neuromonitoring versus visual nerve identification for prevention of recurrent laryngeal nerve injury in adults undergoing thyroid surgery". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1) CD012483. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012483.pub2. PMC 6353246. PMID 30659577.

- ^ Endocrinology: adult and pediatric (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier. 2010. p. Chapter 82. ISBN 978-1-4160-5583-9.

- ^ Hertz BE, Schuller KE (2010). "Saul Hertz, MD (1905-1950): a pioneer in the use of radioactive iodine". Endocrine Practice. 16 (4): 713–5. doi:10.4158/EP10065.CO. PMID 20350908.

- ^ a b Metso S, Auvinen A, Huhtala H, Salmi J, Oksala H, Jaatinen P (May 2007). "Increased cancer incidence after radioiodine treatment for hyperthyroidism". Cancer. 109 (10): 1972–1979. doi:10.1002/cncr.22635. PMID 17393376. S2CID 19734123.

- ^ "levothyroxine". AHFS Patient Medication Information. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- ^ "Radioactive Iodine". MyThyroid.com. 2005. Archived from the original on 5 March 2010. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- ^ Walsh JP, Dayan CM, Potts MJ (July 1999). "Radioiodine and thyroid eye disease". BMJ. 319 (7202): 68–69. doi:10.1136/bmj.319.7202.68. PMC 1116221. PMID 10398607.

- ^ "Radioactive Iodine Therapy: What is it, Treatment, Side Effects". Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ "Radioactive Iodine". American Thyroid Association. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ Berglund J, Christensen SB, Dymling JF, Hallengren B (May 1991). "The incidence of recurrence and hypothyroidism following treatment with antithyroid drugs, surgery or radioiodine in all patients with thyrotoxicosis in Malmö during the period 1970-1974". Journal of Internal Medicine. 229 (5): 435–442. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.1991.tb00371.x. PMID 1710255. S2CID 10510932.

- ^ Esfahani AF, Kakhki VR, Fallahi B, Eftekhari M, Beiki D, Saghari M, et al. (2005). "Comparative evaluation of two fixed doses of 185 and 370 MBq 131I, for the treatment of Graves' disease resistant to antithyroid drugs". Hellenic Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 8 (3): 158–161. PMID 16390021.

- ^ Markovic V, Eterovic D (September 2007). "Thyroid echogenicity predicts outcome of radioiodine therapy in patients with Graves' disease". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 92 (9): 3547–3552. doi:10.1210/jc.2007-0879. PMID 17609305.

- ^ Tintinalli J (2004). Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide (Sixth ed.). McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 1312. ISBN 978-0-07-138875-7.

- ^ a b Zen XX, Yuan Y, Liu Y, Wu TX, Han S (April 2007). "Chinese herbal medicines for hyperthyroidism". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007 (2) CD005450. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005450.pub2. PMC 6544778. PMID 17443591.

- ^ Rieben C, Segna D, da Costa BR, Collet TH, Chaker L, Aubert CE, et al. (December 2016). "Subclinical Thyroid Dysfunction and the Risk of Cognitive Decline: a Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 101 (12): 4945–4954. doi:10.1210/jc.2016-2129. PMC 6287525. PMID 27689250.

- ^ An Appraisal of Endocrinology. John and Mary R. Markle Foundation. 1936. p. 9.

- ^ Fumarola A, Di Fiore A, Dainelli M, Grani G, Carbotta G, Calvanese A (June 2011). "Therapy of hyperthyroidism in pregnancy and breastfeeding". Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey. 66 (6): 378–385. doi:10.1097/ogx.0b013e31822c6388. PMID 21851752. S2CID 28728514.

- ^ a b Moleti M, Di Mauro M, Sturniolo G, Russo M, Vermiglio F (June 2019). "Hyperthyroidism in the pregnant woman: Maternal and fetal aspects". Journal of Clinical & Translational Endocrinology. 16 100190. doi:10.1016/j.jcte.2019.100190. PMC 6484219. PMID 31049292.

- ^ Krassas GE (1 October 2010). "Thyroid Function and Human Reproductive Health". Endocrine Reviews. Volume 31, Issue 5. 31 (5): 702–755. doi:10.1210/er.2009-0041. PMID 20573783.

- ^ Andersen SL, Andersen S, Vestergaard P, Olsen J (April 2018). "Maternal Thyroid Function in Early Pregnancy and Child Neurodevelopmental Disorders: A Danish Nationwide Case-Cohort Study". Thyroid. 28 (4): 537–546. doi:10.1089/thy.2017.0425. PMID 29584590.

- ^ Korevaar TI, Muetzel R, Medici M, Chaker L, Jaddoe VW, de Rijke YB, et al. (January 2016). "Association of maternal thyroid function during early pregnancy with offspring IQ and brain morphology in childhood: a population-based prospective cohort study". The Lancet. Diabetes & Endocrinology. 4 (1): 35–43. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00327-7. hdl:1765/79096. PMID 26497402.

- ^ Carney HC, Ward CR, Bailey SJ, Bruyette D, Dennis S, Ferguson D, et al. (May 2016). "2016 AAFP Guidelines for the Management of Feline Hyperthyroidism". Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 18 (5): 400–416. doi:10.1177/1098612X16643252. PMC 11132203. PMID 27143042.

- ^ Johnson, A. (2014). Small Animal Pathology for Veterinarian Technicians. Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell.

- ^ a b Vaske HH, Schermerhorn T, Armbrust L, Grauer GF (August 2014). "Diagnosis and management of feline hyperthyroidism: current perspectives". Veterinary Medicine: Research and Reports. 5: 85–96. doi:10.2147/VMRR.S39985. PMC 7337209. PMID 32670849.

- ^ Little S (2006). "Feline Hyperthyroidism" (PDF). Winn Feline Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 May 2009. Retrieved 24 June 2009.

- ^ Ford RB, Mazzaferro E (2011). Kirk & Bistner's Handbook of Veterinary Procedures and Emergency Treatment (9th ed.). London: Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 346. ISBN 978-1-4377-0799-1.

- ^ "Hypothyroidism". Merck Veterinary Manual. Archived from the original on 26 May 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ "Leventa-Precautions/Adverse Reactions". Intervet. Archived from the original on 14 January 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ Shadwick SR, Ridgway MD, Kubier A (October 2013). "Thyrotoxicosis in a dog induced by the consumption of feces from a levothyroxine-supplemented housemate". The Canadian Veterinary Journal. 54 (10): 987–989. PMC 3781434. PMID 24155422.

- ^ Broome MR, Peterson ME, Kemppainen RJ, Parker VJ, Richter KP (January 2015). "Exogenous thyrotoxicosis in dogs attributable to consumption of all-meat commercial dog food or treats containing excessive thyroid hormone: 14 cases (2008-2013)". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 246 (1): 105–111. doi:10.2460/javma.246.1.105. PMID 25517332.

Further reading

[edit]- Brent GA, ed. (2010). Thyroid Function Testing. Endocrine Updates. Vol. 28 (1st ed.). New York: Springer. ISBN 978-1-4419-1484-2.

- Ross DS, et al. (October 2016). "2016 American Thyroid Association Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management of Hyperthyroidism and Other Causes of Thyrotoxicosis". Thyroid. 26 (10): 1343–1421. doi:10.1089/thy.2016.0229. PMID 27521067.

- Spadafori G (20 January 1997). "Hyperthyroidism: A Common Ailment in Older Cats". The Pet Connection. Veterinary Information Network. Retrieved 28 January 2007.

- Siraj ES (June 2008). "Update on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Hyperthyroidism" (PDF). Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management. 15 (6): 298–307. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 24 June 2009.

External links

[edit]Hyperthyroidism

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition and Classification

Hyperthyroidism is defined as a condition characterized by excessive production of thyroid hormones by the thyroid gland itself, resulting in elevated circulating levels of thyroxine (T4) and/or triiodothyronine (T3).[3] This overproduction leads to thyrotoxicosis, the clinical syndrome of thyroid hormone excess that manifests as a hypermetabolic state affecting multiple organ systems.[2] In contrast, thyrotoxicosis can occur independently of hyperthyroidism when excess thyroid hormones are derived from exogenous sources, such as factitious thyrotoxicosis caused by surreptitious ingestion of thyroid hormone medications, or from the release of preformed hormones in conditions like thyroiditis, where the gland is inflamed and damaged rather than overactive.[4] Thyroid hormones T3 and T4 play essential roles in regulating basal metabolic rate, protein synthesis, and thermogenesis, influencing nearly every tissue in the body.[5] Under normal conditions, thyroid function is tightly controlled by the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) axis: thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) from the hypothalamus stimulates the anterior pituitary to secrete thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), which in turn prompts the thyroid gland to synthesize and release T4 and T3; elevated thyroid hormone levels exert negative feedback on the hypothalamus and pituitary to suppress further TRH and TSH secretion.[5] Hyperthyroidism is classified in several ways to guide diagnosis and management. Based on origin, it is primarily thyroidal (primary hyperthyroidism), arising from intrinsic thyroid dysfunction, or rarely central (secondary or tertiary), due to inappropriate TSH secretion from pituitary adenomas or hypothalamic disorders, respectively.[6] By severity, it is categorized as overt hyperthyroidism, marked by suppressed TSH levels alongside elevated free T4 and/or T3, or subclinical hyperthyroidism, featuring low TSH with normal thyroid hormone levels, which may be asymptomatic or produce milder effects like subtle tachycardia.[3] Etiologically, common forms include autoimmune causes such as Graves' disease, autonomous thyroid nodules like toxic multinodular goiter, and iodine-induced cases such as the Jod-Basedow phenomenon, where excess iodine exposure triggers hyperthyroidism in iodine-deficient individuals with underlying nodular thyroid disease.[7]Pathophysiology

Hyperthyroidism arises from excessive production or release of thyroid hormones, primarily thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3), disrupting the normal hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis. This excess can result from increased synthesis, often driven by stimulation of the thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) receptor; accelerated release of preformed hormones due to glandular destruction. In the feedback loop, elevated free T4 and T3 levels suppress TSH secretion via negative feedback on the pituitary and hypothalamus, typically leading to low or undetectable TSH in overt hyperthyroidism, as described by the relationship TSH ∝ 1 / (T3 + T4) in simplified terms, where hormone levels inversely regulate pituitary output.[3][8][9] At the cellular level, thyroid hormone synthesis begins with iodide uptake into thyrocytes via the sodium-iodide symporter (NIS), powered by the sodium-potassium ATPase, followed by transport into the colloid by pendrin. Thyroid peroxidase (TPO) then oxidizes iodide to iodine using hydrogen peroxide and catalyzes its incorporation onto tyrosine residues in thyroglobulin, forming monoiodotyrosine (MIT) and diiodotyrosine (DIT). TPO further facilitates the coupling of these iodotyrosines—MIT with DIT to yield T3, or two DIT molecules to produce T4—before proteolysis releases the hormones into circulation. Dysregulation, such as constitutive TSH receptor activation, amplifies these steps, leading to overproduction.[8][3] Systemically, excess thyroid hormones bind nuclear receptors, upregulating genes that increase basal metabolic rate by enhancing Na+/K+-ATPase activity, thereby elevating oxygen consumption and heat production across tissues. This mimics beta-adrenergic stimulation, promoting glycogenolysis, lipolysis, and cardiovascular effects like increased heart rate, independent of catecholamines. Additionally, T3 stimulates osteoclast activity via RANKL expression, accelerating bone resorption and reducing bone mineral density. In specific etiologies, such as Graves' disease, TSH receptor-stimulating antibodies (TRAb) chronically activate the receptor, driving autonomous synthesis; toxic adenomas exhibit somatic TSH receptor mutations that confer nodular independence from TSH; and destructive processes in subacute or postpartum thyroiditis release stored hormones without new synthesis, causing transient excess.[8][9][3]Clinical Presentation

Signs and Symptoms

Hyperthyroidism typically presents with a range of symptoms resulting from excess thyroid hormone, affecting multiple organ systems and varying in severity based on the degree of hormonal elevation. Common general symptoms include heat intolerance, unintentional weight loss despite increased appetite, fatigue, nervousness, irritability, and menstrual irregularities in women.[2][1] Cardiovascular manifestations are prominent and include tachycardia, palpitations, widened pulse pressure, and, in advanced cases, high-output heart failure due to increased metabolic demand.[3][10] Neuromuscular symptoms often involve fine tremor of the hands, proximal muscle weakness (myopathy), anxiety, irritability, hyperreflexia, and insomnia, reflecting heightened sympathetic activity.[1][3] Dermatological and gastrointestinal features encompass warm, moist skin, excessive sweating, thinning or brittle hair, hair loss, increased bowel frequency, and diarrhea, which may be associated with malabsorption of certain nutrients, particularly fats (steatorrhea) and calcium, due to increased gastrointestinal motility, faster intestinal transit time, and reduced time available for absorption. Fat malabsorption is common, with fecal fat levels reaching up to 35 g/day in some cases, while calcium absorption is decreased; although glucose absorption may increase, overall rapid transit interferes with optimal nutrient absorption, stemming from accelerated metabolism and gastrointestinal motility.[2][3][11] Hyperthyroidism may also be associated with lower urinary tract symptoms such as increased urinary frequency, polyuria, urgency, and nocturia. These symptoms, which can occasionally be presenting features, are generally mild and are thought to result from increased renal blood flow, elevated glomerular filtration rate, and altered renal water reabsorption. They typically improve or resolve with effective treatment of the underlying hyperthyroidism. In contrast, hypothyroidism is more commonly associated with reduced urinary frequency, urinary retention, and bladder atony.[12][13] Ocular signs, generalizable across causes but more pronounced in Graves' disease, include lid lag and retraction, which may contribute to a staring appearance.[3][1] A goiter, or enlarged thyroid gland, is present in the majority of Graves' disease cases, the most common etiology of hyperthyroidism, often appearing as diffuse neck swelling.[1][14] In elderly patients, hyperthyroidism may manifest as apathetic hyperthyroidism, with subtler symptoms mimicking depression, such as weight loss, fatigue, apathy, and withdrawal, rather than classic hypermetabolic features.[2][3] Symptom intensity generally correlates with elevated free T4 and T3 levels, though extreme exacerbations like thyroid storm represent acute decompensation beyond typical presentations.[10]Thyroid Storm

Thyroid storm, also known as thyrotoxic crisis, is a rare but life-threatening endocrine emergency characterized by an acute exacerbation of hyperthyroidism, resulting from a sudden and excessive release of thyroid hormones leading to multi-organ dysfunction.[15] It typically occurs in patients with underlying hyperthyroidism, such as Graves' disease, and represents a decompensated state rather than a distinct entity.[15] Common precipitants include infections (the most frequent trigger), surgery (thyroid or non-thyroid), trauma, iodine-containing contrast media, discontinuation of antithyroid therapy, and other stressors like parturition or burns.[15][16] Clinically, thyroid storm manifests with severe systemic symptoms, including high fever exceeding 102°F (38.9°C), often reaching 104–106°F (40–41.1°C); profound tachycardia greater than 140 beats per minute; and central nervous system alterations ranging from agitation and confusion to delirium or coma.[15] Gastrointestinal involvement is prominent, featuring nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and occasionally jaundice due to hepatic dysfunction, while cardiovascular complications such as atrial fibrillation, heart failure, or shock may arise.[15] These features reflect a hypermetabolic crisis with heightened sympathetic activity.[16] Diagnosis relies on clinical assessment, as laboratory confirmation of hyperthyroidism alone is insufficient; the Burch-Wartofsky Point Scale provides a standardized scoring system, assigning points for thermoregulatory dysfunction (e.g., 30 points for temperature >104°F), central nervous system effects (e.g., 30 for coma), gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g., 20 for severe jaundice), and cardiovascular issues (e.g., 15 for severe congestive heart failure), among others, with a score greater than 45 indicating high likelihood of thyroid storm and 25–44 suggesting imminent risk.[15] Elevated free thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) levels with suppressed thyroid-stimulating hormone support the diagnosis but are not specific to the storm.[15] Pathophysiologically, thyroid storm arises from an abrupt surge in circulating thyroid hormones, often triggered by increased release or reduced binding to proteins during acute illness, coupled with enhanced end-organ sensitivity that amplifies sympathetic nervous system hyperactivity, mimicking catecholamine excess and leading to a hyperadrenergic state.[15][16] This cascade promotes widespread tissue oxygen demand, potentially culminating in multi-organ failure, including hepatic congestion, cardiac arrhythmias, and acute respiratory distress.[15] Despite prompt intervention, mortality from thyroid storm has decreased to approximately 1-6% with modern management as of 2025, primarily due to cardiovascular collapse or infection-related complications.[15][17] Its incidence is estimated at approximately 1.4 cases per 100,000 persons per year in females and 0.7 per 100,000 in males, with higher rates among hospitalized patients.[18]Causes

Autoimmune Causes

Autoimmune causes of hyperthyroidism primarily involve dysregulated immune responses targeting the thyroid gland, leading to excessive hormone production or release. The most common etiology is Graves' disease, an organ-specific autoimmune disorder characterized by the production of thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulins (TSI or TRAb) that bind to and activate the thyrotropin receptor (TSHR) on thyroid follicular cells, mimicking the action of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and causing diffuse glandular hyperplasia and hyperfunction.[19][14] These autoantibodies stimulate cyclic AMP production, promoting thyroid hormone synthesis and secretion, which accounts for 60-80% of hyperthyroidism cases in iodine-sufficient regions worldwide.[20][14] The pathogenesis of Graves' disease involves both humoral and cellular immunity, with B cells producing the pathogenic TRAb and T cells providing helper functions through cytokine release that amplify the autoimmune response.[21][22] Genetic susceptibility plays a key role, with associations to human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles such as HLA-DR3, which influences antigen presentation and T-cell activation in thyroid tissue.[23] Environmental factors can trigger or exacerbate the disease in genetically predisposed individuals, including cigarette smoking, which increases risk by promoting oxidative stress and immune dysregulation; psychological stress, potentially via neuroendocrine pathways; and excess iodine intake, which may enhance autoantigen presentation.[24][25] Graves' disease exhibits a marked female predominance, with a female-to-male ratio of 5-10:1, likely influenced by estrogen-mediated immune modulation.[26][27] It is also associated with other autoimmune conditions, such as vitiligo and rheumatoid arthritis, reflecting shared genetic and immunological pathways that heighten overall autoimmunity risk.[28] In some cases, TSHR autoantibodies cross-react with orbital antigens, contributing to extrathyroidal manifestations like ophthalmopathy through shared immunogenic epitopes.[29] Other autoimmune etiologies include transient hyperthyroid phases in conditions like hashitoxicosis and postpartum thyroiditis. Hashitoxicosis represents an initial destructive hyperthyroid state in Hashimoto's thyroiditis, where antibody-mediated (anti-thyroid peroxidase or anti-thyroglobulin) inflammation causes follicular disruption and release of preformed thyroid hormones, typically resolving into hypothyroidism.[30][31] Postpartum thyroiditis, occurring in 5-10% of women within the first year after delivery, involves a similar autoimmune destructive process driven by rebound T-cell and antibody activity following pregnancy-induced immune suppression, often presenting with a hyperthyroid phase due to hormone leakage before progressing to hypothyroidism in many cases.[32][33] These conditions highlight the spectrum of autoimmune thyroiditis, where initial hyperthyroidism stems from glandular destruction rather than stimulation.Non-Autoimmune Causes

Non-autoimmune causes of hyperthyroidism encompass structural abnormalities in the thyroid gland, inflammatory conditions leading to hormone release, and exogenous factors that disrupt normal thyroid function. These differ from autoimmune etiologies by lacking antibody-mediated stimulation, instead involving autonomous hormone production or leakage of pre-formed hormones.[2] Toxic nodular goiter, also known as toxic multinodular goiter, arises from multiple autonomous thyroid nodules that independently produce excess thyroid hormone, often appearing as "hot" areas on scintigraphy with suppressed uptake in surrounding tissue. This condition is more prevalent in iodine-deficient regions, where the incidence is 1.5-18 cases per 100,000 person-years, compared to lower rates in iodine-sufficient areas. It typically affects older adults and develops gradually from longstanding non-toxic goiter.[34][9] Toxic adenoma refers to a single hyperfunctioning thyroid nodule that autonomously secretes thyroid hormones, accounting for approximately 5-10% of hyperthyroidism cases, particularly in iodine-deficient populations. These benign tumors suppress TSH levels and function independently of regulatory signals, leading to clinical hyperthyroidism without systemic autoimmunity. They are more common in women and often present as a palpable solitary nodule.[35][36] Thyroiditis variants represent inflammatory processes that cause transient hyperthyroidism through destructive release of stored thyroid hormones, rather than increased synthesis. Subacute thyroiditis, often viral in origin and associated with upper respiratory infections, presents with painful thyroid enlargement, fever, and elevated inflammatory markers; it affects women more frequently and resolves spontaneously in most cases. Silent thyroiditis, a painless form, involves lymphocytic infiltration and hormone leakage, commonly seen postpartum but also in non-pregnant individuals without evident autoimmunity. Drug-induced thyroiditis, triggered by agents like amiodarone or lithium, disrupts follicular integrity; amiodarone, for instance, can induce type 1 thyrotoxicosis via iodine excess in susceptible glands or type 2 through direct cytotoxicity.[37][38][39] Exogenous causes stem from external thyroid hormone or iodine overload, mimicking endogenous hyperthyroidism biochemically but with low or absent thyroidal radioiodine uptake. Iatrogenic hyperthyroidism results from excessive levothyroxine dosing in hypothyroidism treatment, emphasizing the need for regular TSH monitoring to prevent overdose. Factitious hyperthyroidism, or thyrotoxicosis factitia, involves surreptitious ingestion of thyroid hormone preparations, often for weight loss or psychological reasons, and is characterized by suppressed thyroglobulin levels. Iodine excess, from supplements, contrast agents, or medications like amiodarone, can precipitate hyperthyroidism in predisposed individuals with underlying nodular disease, as high iodine loads overwhelm the gland's regulatory mechanisms.[2][3] Rare non-autoimmune causes include gestational trophoblastic disease, where markedly elevated human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) from molar pregnancies or choriocarcinomas cross-reacts with the TSH receptor, stimulating thyroid hormone production; this can occur in up to 20-50% of complete hydatidiform mole cases with hCG levels exceeding 100,000 IU/L.[40][41][42] Rarely, TSH-secreting pituitary adenomas (TSHomas) cause central hyperthyroidism by autonomous TSH production, accounting for less than 1% of cases.[43]Diagnosis

Laboratory Tests

The diagnosis of hyperthyroidism begins with biochemical confirmation through thyroid function tests, typically prompted by symptoms such as unexplained weight loss or palpitations.[2] The primary screening test is serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), which is suppressed in hyperthyroidism due to negative feedback from excess thyroid hormones.[44] A TSH level below 0.1 mU/L is highly suggestive of hyperthyroidism, particularly when accompanied by elevated free thyroxine (T4) or triiodothyronine (T3).[45] Overt hyperthyroidism is characterized by low TSH with elevated free T4 and/or total T3 levels, confirming excess thyroid hormone production. In hyperthyroidism involving increased hormone synthesis (e.g., Graves' disease or toxic nodular goiter), serum thyroglobulin (Tg) levels are typically elevated due to enhanced glandular stimulation and synthesis, alongside elevated T3 and T4 with suppressed TSH; this contrasts with lower Tg in destructive thyroiditis or exogenous causes.[46][47] In subclinical hyperthyroidism, TSH is low or undetectable while free T4 and T3 remain within normal ranges, often representing an early or mild form of the condition.[48] Some cases, particularly in Graves' disease, exhibit T3-predominant hyperthyroidism, where T3 levels are disproportionately elevated compared to T4.[27] To identify the underlying etiology, antibody assays are essential. Thyrotropin receptor antibodies (TRAb), including thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulins (TSI), are positive in over 90% of Graves' disease cases and confirm autoimmune stimulation of the thyroid.[48] In contrast, anti-thyroid peroxidase (anti-TPO) and anti-thyroglobulin (anti-Tg) antibodies may be elevated in destructive thyroiditis, indicating autoimmune-mediated thyroid damage rather than overproduction.[49] Ancillary laboratory tests provide supportive evidence and assess complications. A complete blood count (CBC) often reveals mild anemia due to increased red blood cell turnover, while leukocytosis with a left shift may occur in thyroid storm, a severe manifestation of hyperthyroidism.[50] Liver enzymes, such as alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), are frequently elevated in 15-76% of untreated cases, reflecting direct effects of excess thyroid hormones on hepatic function.[51] Hypercalcemia, resulting from accelerated bone turnover and resorption, is observed in up to 20% of patients and can contribute to symptoms like fatigue.[52] In amiodarone-induced hyperthyroidism, measurement of reverse T3 (rT3) is useful; elevated rT3 levels with high T4 but relatively low T3 help distinguish type 2 (destructive thyroiditis-like) from type 1 (iodine-induced overproduction).[53] These tests collectively guide differentiation from other causes, with further imaging reserved for etiological confirmation.[47]Imaging and Other Studies

Thyroid scintigraphy serves as a primary imaging modality for evaluating the etiology of hyperthyroidism by assessing thyroid gland function and structure through the administration of radiotracers such as iodine-123 (123I) or technetium-99m pertechnetate (99mTc-pertechnetate).[54][55] In Graves' disease, this test typically reveals diffusely increased radioiodine uptake, often exceeding 30% at 24 hours, reflecting enhanced thyroid activity, whereas uptake is low or suppressed in destructive thyroiditis due to impaired hormone synthesis.[54][56] The scan also distinguishes hyperfunctioning "hot" nodules, indicative of toxic adenomas, from non-functioning "cold" nodules that may warrant further evaluation for malignancy.[57] Additionally, whole-body scintigraphy can detect ectopic thyroid tissue, such as in struma ovarii, contributing to hyperthyroidism in rare cases.[58] Ultrasound provides detailed anatomical assessment of the thyroid, particularly useful for characterizing nodules and evaluating parenchymal changes in hyperthyroidism.[59] In Graves' disease, color Doppler ultrasonography often demonstrates markedly increased intrathyroidal vascularity, known as the "thyroid inferno" pattern, which correlates with disease activity.[60] For nodular hyperthyroidism, the Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data System (TIRADS) scoring system stratifies nodules based on ultrasound features like composition, echogenicity, margins, calcifications, and shape to estimate malignancy risk and guide biopsy decisions.[61][62] Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is employed when evaluating large goiters or retrosternal extension, providing critical information on tracheal compression, vascular involvement, and surgical planning.[63][64] These modalities are particularly valuable in cases where ultrasound is limited by anatomy or when assessing compressive symptoms. Positron emission tomography (PET), typically with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG), is rarely indicated but may be used in suspected thyroid malignancy or to evaluate incidentalomas detected on other imaging.[65][66] Functional tests like thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) stimulation, which provoke a blunted or absent thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) response in overt hyperthyroidism, have largely been supplanted by more sensitive laboratory assays and are now rarely performed.[67][68]Subclinical Hyperthyroidism

Subclinical hyperthyroidism is defined as a persistently suppressed serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level, typically below 0.1 mU/L, accompanied by normal levels of free thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3).[45] This condition reflects mild thyroid hormone excess without overt clinical symptoms, distinguishing it from manifest hyperthyroidism.[69] Its prevalence in the general population ranges from 0.5% to 2%, with higher rates observed in older adults and regions with iodine deficiency.[45] In the United States, subclinical hyperthyroidism affects approximately 0.7% to 1.4% of individuals overall, rising to 1% to 8% among those over 65 years.[9][45] The condition carries several health risks, particularly in vulnerable populations. It is associated with a 2- to 3-fold increased risk of atrial fibrillation, especially when TSH is below 0.1 mU/L and in patients over 60 years, contributing to higher rates of cardiovascular events such as coronary heart disease and stroke.[45][70] Bone health is also affected, with accelerated bone loss and a higher incidence of osteoporosis and fractures in postmenopausal women.[71] Additionally, subclinical hyperthyroidism has been linked to cognitive decline, reduced quality of life, and increased overall mortality, though these associations are more pronounced with prolonged duration and lower TSH levels.[45] Recent data emphasize that cardiovascular risks escalate significantly with TSH suppression below 0.1 mU/L, independent of other factors.[70] Progression to overt hyperthyroidism occurs at a rate of 2% to 5% per year on average, though this can reach up to 7% annually in cases with very low TSH or underlying Graves' disease, and is higher among the elderly.[69] Conversely, spontaneous normalization of TSH levels happens in up to 12% of cases per year.[72] Routine screening for subclinical hyperthyroidism is not recommended by major guidelines, including for high-risk groups such as individuals over 65 years; however, if detected through testing prompted by symptoms or other indications, evaluation and management are advised.[45][73] Management focuses on risk stratification rather than universal treatment. Intervention with antithyroid medications or other therapies is recommended for patients over 65 years with TSH below 0.1 mU/L, or those with comorbidities such as atrial fibrillation, heart disease, or osteoporosis, to mitigate associated risks.[69] For milder cases (TSH 0.1-0.4 mU/L) or younger patients without symptoms, periodic monitoring of TSH levels every 6 to 12 months is sufficient, with reassessment for progression or complications.[45] This approach balances potential benefits against treatment side effects, guided by clinical guidelines from endocrine societies.[70]Treatment

Antithyroid Medications