Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Boer commando

View on Wikipedia| Kommando | |

|---|---|

| |

| Active | 18th century–1902 |

| Country | |

| Branch | Militia |

| Type | Guerrilla fighter, military volunteer |

| Engagements | Boer Wars, Xhosa Wars |

The Boer Commandos or "Kommandos" were volunteer military units of guerrilla militia organized by the Boer people of South Africa. From this came the term "commando" into the English language during the Second Boer War of 1899–1902 as per Costica Andrew.

History

[edit]

In 1658, war erupted between the Dutch settlers at Cape Colony and the Khoi-khoi. In order to protect the settlement, all able bodied men were conscripted. After the conclusion of this war, all men in the colony were liable for military service and were expected to be ready on short notice.

By 1700, the size of the colony had increased immensely and it was divided into districts. The small military garrison stationed at the Castle de Goede Hoop could not be counted on to react swiftly in the border districts, therefore the commando system was expanded and formalized. Each district had a Kommandant who was charged with calling up all burghers in times of need. During the first British invasion of the Cape Colony in 1795 and the second invasion in 1806, the commandos were called up to defend the Cape Colony. During the Battle of Blaauwberg in January 1806, the Swellendam Commando held the British off long enough for the rest of the Batavian army to retreat to safety.

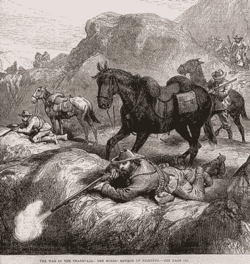

Under British rule, the Cape Colony continued to use the commando system in its frontier wars, in addition to regular British imperial troops. Boer commandos fought alongside Fengu, British settlers, Khoi-khoi and other ethnic groups in units which were often mixed. Light, mobile commandos were undeniably better-suited than the slow-moving columns of imperial troops, for warfare in the rough frontier mountains. However, tensions often arose in the Cape's government over the relative merits and control of these two parallel military systems.[1]

During the Great Trek, this system was used and remained in use in the Boer republics. Both republics issued commando laws, making commando service mandatory in times of need for all male citizens between the ages of 16 and 60. During the Second Boer War (1899–1902) the Boer commando formed the backbone of the Boer forces.

After the declaration of peace in 1902, the commandos were disbanded. They did re-form themselves in clandestine "shooting clubs". In 1912, the commandos were re-formed as an Active Citizen Force in the Union Defence Force. This system was in operation until 2005, when all commandos were disbanded again.

Structure

[edit]

Each commando was attached to a town, after which it was named (e.g. Bloemfontein Commando). Each town was responsible for a district, divided into wards. The commando was commanded by a kommandant and each ward by a veldkornet or field cornet (equivalent of a senior NCO rank)

The veldkornet was responsible not only for calling up the burghers, but also for policing his ward, collecting taxes, issuing firearms and other materiel in times of war. Theoretically, a ward was divided into corporalships. A corporalship was usually made up of about 20 burghers. Sometimes entire families (fathers, sons, uncles, cousins) filled a corporalship.

The veldkornet was responsible to the kommandant, who in turn was responsible to a general. In theory, a general was responsible for four commandos. He in turn was responsible to the commander-in-chief of the republic. In the Transvaal, the C-in-C was called the Commandant-General and in the Free State the Hoofdkommandant (Chief Commandant). The C-in-C was responsible to the president.

Other auxiliary ranks were created in war time, such as vleiskorporaal ("meat corporal"), responsible for issuing rations.

The commando was made up of volunteers, all officers were appointed by the members of the commando, and not by the government. This gave a chance for some commanders to appear, such as General Koos de la Rey and General C. R. de Wet, but also had the disadvantage of sometimes putting inept commanders in charge. Discipline was also a problem, as there was no real way of enforcing it.

The various Boer republics did not all have the same command structure.[2]

Weaponry

[edit]Before the Second Boer War, the republics' most popular rifle was the .450 Westley Richards, a falling-block, single-action, breech-loading model rifle, with accuracy up to 600 yards. Some were marked "Made Specially For Z.A.R.".[3] These were similar to the Martini-Henry Mark II rifles used by British troops.[4][5] A book about the war (J. Lehmann's The First Boer War, 1972) offered this comment about the Boers' rifle: "Employing chiefly the very fine breech-loading Westley Richards - calibre 45; paper cartridge; percussion-cap replaced on the nipple manually - they made it exceedingly dangerous for the British to expose themselves on the skyline".[6] During the First Boer War some older Boers preferred the duel purposed percussion cap breechloading Monkey Tail, also made by Westley Richards.[7]

For the Anglo-Boereoorlog ("Anglo-Boer War"), Paul Kruger, President of the South African Republic, re-equipped the army, importing 37,000 of the latest Mauser Model 1895 rifles[8] and some 40 to 50 million rounds of 7x57 ammunition.[9] The Model 1895 was also known as "Boer Model" Mauser [10] and was marked “O.V.S” (Oranje Vrij Staat) just above the serial number.[11] This German-made rifle had a firing range exceeding 2,000 yards. Experienced shooters could achieve excellent long-range accuracy.[12] Some commandos used the Martini-Henry Mark III, since thousands of these had also been purchased; the drawback was the large puff of white smoke after firing which gave away the shooter's position.[13][14]

Roughly 7,000 Guedes 1885 rifles were also purchased a few years earlier and these were used during the hostilities.[15]

Others used captured British rifles such as the "long" Lee-Metford and the Enfield, as confirmed by photographs from the era.[16][17] When the ammunition for the Mausers ran out,[18] the Boers relied primarily on the captured Lee-Metfords.[19][20]

Regardless of the rifle, few of the commando used bayonets.[21][22]

The best modern European artillery was also purchased. By October 1899 the Transvaal State Artillery had 73 heavy guns, including four 155 mm Creusot fortress guns[23] and 25 of the 37 mm Maxim Nordenfeldt guns.[24] The Boers' Maxim, larger than the Maxim model used by the British,[25] was a large caliber, belt-fed, water-cooled "auto cannon" that fired explosive rounds (smokeless ammunition) at 450 rounds per minute; it became known as the "Pom Pom".[26]

Other weapons in use included:

- Mauser C96 pistol

- Colt Single Action Army revolver

- Remington Model 1875 revolver

- Remington Rolling Block rifle

- Winchester rifle

- Vetterli rifle

- Gewehr 1888

- Krag–Jørgensen rifle

- Kropatschek rifle

- Lee–Enfield[27]

- Lee–Metford[28]

- Martini–Henry[29]

- Guedes Rifle[30]

- Enfield revolver

- Mauser Zig-Zag

- M1879 Reichsrevolver

List of Boer Commando units

[edit]The following Boer commandos existed in the Orange Free State and Transvaal:[31]

Orange Free State

[edit]- Bethlehem

- Bethulie

- Bloemfontein

- Boshof

- Bothaville

- Brandfort

- Caledon River

- Edenburg

- Fauresmith

- Ficksburg

- Frankfort

- Harrismith

- Heilbron

- Hoopstad

- Jacobsdal

- Kroonstad

- Ladybrand

- Lindley

- Parys

- Philippolis

- Rouxville

- Senekal

- Smithfield

- Thaba Nchu

- Ventersburg

- Vrede

- Vredefort

- Wepener

- Winburg

Transvaal

[edit]- Amsterdam

- Bethal

- Bloemhof

- Boksburg

- Carolina

- Christiana

- Elandsfontein

- Elands River

- Ermelo

- Fordsburg

- Germiston

- Heidelberg

- Jeppestown

- Johannesburg

- Klerksdorp

- Krugersdorp

- Lichtenburg

- Lydenburg

- Marico

- Middelburg

- Piet Retief

- Potchefstroom

- Pretoria

- Rustenburg

- Standerton

- Swaziland

- Utrecht

- Vryheid

- Wakkerstroom

- Waterberg

- Wolmaransstad

- Zoutpansberg

- Zwartruggens

See also

[edit]References and notes

[edit]- ^ RD staff (1996). Xhosa Wars. Reader's Digest Family Encyclopedia of World History. The Reader's Digest Association.

- ^ Angloboerwar website Archived 2009-07-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ https://www.labuschagne.info/small-arms.htm, Small Arms of the Boer War

- ^ "Firearms and Firepower - First War of Independence, 1880-1881 - South African Military History Society - Journal". samilitaryhistory.org. Retrieved 2024-02-29.

- ^ https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/victorians/boer_wars_01.shtml, Boer Wars

- ^ "Firearms and Firepower - First War of Independence, 1880-1881 - South African Military History Society - Journal". samilitaryhistory.org. Retrieved 2024-02-29.

- ^ Laband, John (2018). The Battle of Majuba Hill: The Transvaal Campaign, 1880–1881. Warwick, England: Helion and Company. p. 40. ISBN 978-1911512387.

- ^ "An Official Journal Of The NRA | The Guns of the Boer Commandos". An Official Journal Of The NRA. Retrieved 2024-02-29.

- ^ Bester 1994, p. [page needed]; Wessels 2000, p. 80.

- ^ "The Model 1893/95 "Boer Model" Mauser". Shooting Times. 23 September 2010. Retrieved 2016-03-18.

- ^ https://www.shootingtimes.com/editorial/longgun_reviews_st_boermodel_201007/99362, The Model 1893/95 "Boer Model" Mauser

- ^ Murray, Nicholas (2013-08-31). The Rocky Road to the Great War: The Evolution of Trench Warfare to 1914. Potomac Books, Inc. ISBN 978-1-61234-105-7.

- ^ Scarlata, Paul (2017-04-17). "6 Rifles Used by the Afrikaners During the Second Boer War". Athlon Outdoors. Retrieved 2024-02-29.

- ^ Pretorius, Fransjohan (1999). Life on Commando During the Anglo-Boer War, 1899-1902. Human & Rousseau. ISBN 978-0-7981-3808-6.

- ^ Scarlata, Paul (2017-04-17). "6 Rifles Used by the Afrikaners During the Second Boer War". Athlon Outdoors. Retrieved 2024-02-29.

- ^ "An Official Journal Of The NRA | The Guns of the Boer Commandos". An Official Journal Of The NRA. Retrieved 2024-02-29.

- ^ "BBC - History - The Boer Wars". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2024-02-29.

- ^ "An Official Journal Of The NRA | The Guns of the Boer Commandos". An Official Journal Of The NRA. Retrieved 2024-02-29.

- ^ Muller, C. F. J. (1986). Five Hundred Years: A History of South Africa. Academica. ISBN 978-0-86874-271-7.

- ^ Grant, Neil (2015-03-20). Mauser Military Rifles. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4728-0595-9.

- ^ Gooch, John (2013-10-23). The Boer War: Direction, Experience and Image. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-27181-7.

- ^ Grant, Neil (2015-03-20). Mauser Military Rifles. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4728-0595-9.

- ^ Lunderstedt, Steve (2000). From Belmont to Bloemfontein: The Western Campaign of the Anglo-Boer War, February 1899 to April 1900. Diamond Fields Advertiser. ISBN 978-0-620-26099-2.

- ^ Wessels 2000, p. 80

- ^ Horn, Bernd (2012-12-22). Doing Canada Proud: The Second Boer War and the Battle of Paardeberg. Dundurn. ISBN 978-1-4597-0578-4.

- ^ http://www.smallarmsreview.com/display.article.cfm?idarticles=2490, SOUTH AFRICA’S NATIONAL MUSEUM OF MILITARY HISTORY

- ^ Association, National Rifle. "An Official Journal Of The NRA | The Guns of the Boer Commandos". An Official Journal Of The NRA. Retrieved 2022-12-11.

- ^ Association, National Rifle. "An Official Journal Of The NRA | The Guns of the Boer Commandos". An Official Journal Of The NRA. Retrieved 2022-12-11.

- ^ Association, National Rifle. "An Official Journal Of The NRA | The Guns of the Boer Commandos". An Official Journal Of The NRA. Retrieved 2022-12-11.

- ^ Association, National Rifle. "An Official Journal Of The NRA | The Guns of the Boer Commandos". An Official Journal Of The NRA. Retrieved 2022-12-11.

- ^ Hall, Darrell (1999). The Hall Handbook of the Anglo-Boer War, 1899-1902. Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press. pp. 13–17. ISBN 9780869809495.

Sources

[edit]- Wessels, André (2000). "Afrikaners at War". In Gooch, John (ed.). The Boer War: Direction, Experience and Image. London: Cass.

- Bester, Ron (1994). Boer Rifles and Carbines of the Anglo–Boer War. Bloemfontein: War Museum of the Boer Republics. ISBN 1874979022.

Boer commando

View on GrokipediaA Boer commando was a district-based militia unit in the Boer republics of the Transvaal (South African Republic) and Orange Free State, comprising able-bodied white male burghers aged 16 to 60 mobilized as mounted infantry for defense against external threats.[1][2] These units lacked a fixed size, varying by local population, and operated without a standing professional army, relying instead on citizen-soldiers who supplied their own horses, rations, and firearms—often modern Mauser rifles provided by the republics.[2] Leadership was decentralized, with officers typically elected based on experience, enabling rapid decision-making suited to irregular warfare.[1] Originating in the 18th century from the need to raise forces for frontier defense, the commando system emphasized mobility, marksmanship, and intimate knowledge of the terrain, allowing small groups to conduct hit-and-run raids and ambushes effectively.[1] In the First Anglo-Boer War (1880–1881), commandos decisively repelled British invasions, securing Boer independence through victories at Laing's Nek and Majuba Hill.[3] During the Second Anglo-Boer War (1899–1902), approximately 55,000 burghers initially formed commandos that achieved early successes, such as capturing British artillery at Colenso and besieging key towns like Ladysmith and Kimberley, despite facing a much larger British expeditionary force.[2] As conventional battles turned against them, commandos shifted to prolonged guerrilla tactics, disrupting British supply lines and communications, which astonished observers with the resilience of decentralized irregular forces armed with modern weapons.[4] This phase extended the conflict, inflicting significant casualties—over 20,000 British dead or wounded—but ultimately succumbed to Britain's scorched-earth policies and blockhouse system, though the commandos' effectiveness highlighted the challenges of countering motivated citizen militias in familiar terrain.[2][5]

Origins and Historical Development

Frontier Militia Roots

The commando system originated in the Dutch Cape Colony during the late 17th century as the primary mechanism for frontier defense and expansion against indigenous Khoisan groups. Established under the Dutch East India Company (VOC) following initial conflicts like the Khoikhoi-Dutch wars of 1659–1660, commandos consisted of mounted expeditions of conscripted burghers—free male settlers—who provided their own horses, rifles, and provisions for short-term mobilizations.[6][7] These units operated beyond the limited VOC garrison in Cape Town, enabling trekboers (semi-nomadic frontier farmers) to conduct punitive raids against Khoikhoi cattle raiders and San hunter-gatherers accused of stock theft, often resulting in the capture of women and children as laborers.[6][8] By the mid-18th century, as Boer settlement pushed eastward into the Zuurveld region, commandos adapted to larger-scale threats from Xhosa cattle herders, marking the onset of the Cape Frontier Wars. In the First Frontier War (1779–1781), burgher militias from eastern districts like Swellendam and Graaff-Reinet were mobilized to repel Xhosa incursions and reclaim stolen livestock, with operations escalating into systematic drives to clear indigenous groups from contested grazing lands.[9][10] The Second Frontier War (1789–1793) saw similar commando actions, where decentralized units under local commandants pursued Xhosa forces across the Fish River, demonstrating the system's reliance on rapid assembly and intimate knowledge of rugged terrain over formal military hierarchy.[10][7] This militia structure emphasized universal male obligation, with districts divided into wards each led by a veldkornet (field cornet) responsible for mustering 20–60 armed horsemen for service periods typically lasting weeks.[11] Elected or appointed locally, these leaders coordinated with higher commandants, but decisions often reflected burgher consensus, prioritizing mobility and marksmanship honed from hunting and herding.[11] The system's effectiveness stemmed from its alignment with Boer agrarian lifestyles—self-sufficient, horse-dependent, and geared toward irregular warfare—rather than standing armies, a model that persisted through British occupation after 1795 and into the inland migrations of the 1830s.[7][12]Formalization in Boer Republics

In the South African Republic (Transvaal), the commando system was formalized following independence from Britain via the Sand River Convention on 17 January 1852, establishing a militia framework where all white male burghers aged 16 to 60 were obligated to provide personal military service upon mobilization, supplying their own horses, rifles, and 30 rounds of ammunition.[12] This obligation was codified in the republic's Grondwet (constitution) promulgated on 18 April 1858, which divided the territory into districts each headed by an elected commandant responsible for raising and leading local commandos in defense against threats.[13] By the 1890s, under Commandant-General Piet Joubert, the system was further structured into 17 districts, with commandos organized into field cornetcies of approximately 50-60 men each, led by elected field cornets reporting to district commandants; leadership positions required burgher approval, emphasizing democratic accountability over hierarchical imposition.[12] The Orange Free State similarly institutionalized the commando upon independence recognized by the Bloemfontein Convention on 23 February 1854, enacting a Commando Act that year mandating service for all white male residents aged 16 to 60 without legal exemption, with burghers expected to equip themselves analogously to Transvaal standards, including horses for mounted operations.[14] The president's role as commander-in-chief was outlined in the state's 1854 constitution, with a chief commandant elected during wartime by assembled commandants and field cornets to coordinate district-based units, mirroring the Transvaal's regional structure but adapting to the Free State's smaller population of about 77,000 burghers by 1899.[12] Both republics reinforced these frameworks with later legislation—the Transvaal's 1898 Commando Act and the Orange Free State's 1899 equivalent—imposing fines or imprisonment for disciplinary breaches, such as desertion or failure to report, to address growing threats from British expansionism.[13] This formalization reflected the republics' agrarian, decentralized societies, prioritizing rapid mobilization over professional standing armies; commandos remained part-time citizen militias, trained informally through hunting and frontier defense, with no full-time pay but allowances for horse forage during active service.[12] By the eve of the Second Anglo-Boer War in October 1899, these systems enabled the Transvaal to field around 23,000-25,000 burghers and the Orange Free State 12,000, organized into roughly 60-70 commandos total, demonstrating the efficacy of compulsory, self-reliant service in sustaining republican sovereignty.[13]Organization and Command Structure

District-Based Recruitment

The Boer republics of the South African Republic (Transvaal) and Orange Free State organized their militia through district commandos, with each administrative district required to form a commando manned by its resident burghers.[15][1] Districts, overseen by a civil landdrost and military commandant, were subdivided into wards led by veldkornets (field cornets), who commanded smaller corps of 20 to 60 men each.[15] Every able-bodied white male burgher aged 16 to 60 faced compulsory service, expected to supply their own rifle, at least 30 rounds of ammunition, horse, saddle, bridle, and initial provisions.[15] The state provided limited support, such as subsidized rifles for those without, but emphasized personal responsibility to facilitate quick mobilization.[15] Upon governmental call-up, district commandants assembled commandos via elected officers and local networks, drawing on universal male obligation without standing armies.[15] Commando strength varied by district population: rural areas yielded hundreds of men, while populous urban districts like Pretoria or Bloemfontein could muster up to 3,000.[12] Examples include Transvaal's 29 districts (e.g., Carolina, Boksburg) and Orange Free State's 29 (e.g., Bethlehem, Winburg), each maintaining distinct units.[1] This decentralized recruitment fostered intimate knowledge of local terrain among fighters and enabled flexible, community-driven responses, though it depended on burgher discipline and initiative rather than centralized conscription.[15]Leadership and Decision-Making

The leadership structure of Boer commandos was rooted in the democratic principles of the Boer republics, where officers were elected by the burghers rather than appointed through centralized authority. The field cornet, the basic unit leader responsible for a ward of approximately 20-40 families, was elected directly by the local burghers and handled mobilization, arms distribution, and initial command during musters.[1] In larger wards, an assistant field cornet could be similarly elected to support these duties.[1] District-level commandants, overseeing the commando as a whole (typically 500-1,000 men), were elected by the burghers of the district, with terms fixed at five years in the Transvaal Republic.[1] [15] Higher echelons maintained this elective tradition, though with wartime adaptations for efficiency. In the Transvaal, the commandant-general was elected every five years by universal male burgher suffrage, serving as the overall military head without a formal staff, relying instead on civilian aides.[1] The Orange Free State vested peacetime command in the state president, but during war, a chief commandant was elected by assembled commandants and field cornets, with combat generals (or vecht generals) appointed to coordinate multiple commandos.[1] [11] All ranks, including corporals, derived authority from burgher confidence rather than coercion, as Boer law backed elections but emphasized voluntary service over enforced discipline.[15] [13] Decision-making in commandos prioritized consensus and local initiative over rigid hierarchy, enabling adaptability in guerrilla operations but complicating unified strategy. Leaders "led rather than commanded," lacking executive power to issue binding orders; instead, they persuaded through personal influence and burgher loyalty, with field cornets acting as "first among equals."[1] [13] Burgher opinion directly shaped plans, as officers faced critique or replacement if perceived as ineffective—evident in the Transvaal's 1899 decision to besiege Kimberley, driven by popular demand despite strategic risks.[1] This system boosted morale and tactical flexibility, particularly in the Second Anglo-Boer War's guerrilla phase (1900-1902), but electoral politics sometimes delayed responses or fragmented efforts in conventional battles, as noted by observers critiquing the erasure of merit-based traces in favor of popularity.[16]Tactics and Operational Methods

Guerrilla Warfare Principles

![Boer commandos with captured British prisoners during the guerrilla phase][float-right] The Boer commandos transitioned to guerrilla warfare following the fall of Pretoria on June 5, 1900, and Bloemfontein on March 13, 1900, after initial conventional defeats, adopting principles formalized in krijgsraads (war councils) such as the one held in Kroonstad on March 17, 1900.[5] [17] These decisions emphasized three core tenets: weeding out unreliable fighters to ensure commitment, striking British lines of communication to disrupt logistics, and avoiding decisive pitched battles to preserve forces.[5] This strategy leveraged the Boers' superior horsemanship and intimate knowledge of the veld terrain, enabling persistent harassment without risking annihilation.[18] Central to Boer guerrilla principles was mobility, achieved by organizing into small, dispersed units of 100-300 mounted burghers who abandoned cumbersome wagon trains for lighter, self-sufficient operations.[5] These commandos conducted hit-and-run raids, using speed and surprise to target vulnerable British supply convoys, railway lines, and isolated outposts, as exemplified by Christiaan de Wet's ambush at Sannah's Post on March 31, 1900, where 350 Boers inflicted 159 casualties and captured 421 prisoners with minimal losses.[5] By dispersing into independent columns under leaders like de Wet and Jacobus Herculaas de la Rey, the Boers maximized operational flexibility, evading larger British formations and exploiting the vast South African interior to prolong the conflict.[19] Another key principle involved selective engagement and intelligence, prioritizing attacks on British weaknesses while relying on local Boer populations for sustenance and information, thereby minimizing logistical vulnerabilities.[18] Commandos avoided fortified positions, instead using long-range Mauser rifles for sniping and ambushes from cover, which compounded British difficulties in an era of smokeless powder and entrenched defenses.[5] This approach inflicted disproportionate attrition, with Boer forces wrecking trains and depots—such as de Wet's destruction of £500,000 in supplies at Roodewal on June 7, 1900—while sustaining their campaign through foraging and family support networks.[5] The principles' effectiveness stemmed from causal alignment with Boer societal strengths: decentralized decision-making in field commandos and cultural resilience honed by frontier life, though ultimate British countermeasures like blockhouses eroded these advantages by mid-1901.[18]Adaptation to Terrain and Mobility

Boer commandos adapted to the diverse South African terrain—encompassing open highveld grasslands, kopjes, dongas, and bushveld—through intimate local knowledge derived from agrarian lifestyles and hunting practices, enabling effective concealment and ambush positions. This expertise allowed them to exploit natural features for defensive advantages, as demonstrated during the "Black Week" setbacks for British forces in December 1899, where Boers used terrain familiarity to entrench at Magersfontein, Stormberg, and Colenso, inflicting heavy casualties on exposed British advances.[20][21] Mobility formed the cornerstone of commando operations, with burghers mobilizing on horseback using hardy, locally bred ponies accustomed to traversing rugged landscapes and enduring harsh conditions from prior use in herding and pursuit activities. Each fighter provided his own mount, rifle, 50 rounds of ammunition (later reduced to 30), and rations sufficient for eight days, facilitating lightweight, self-reliant units capable of covering extensive distances rapidly without reliance on supply lines.[11][22][23] During the guerrilla phase of the Second Anglo-Boer War from mid-1900 onward, commandos fragmented into smaller, decentralized bands that leveraged terrain cover to conduct hit-and-run raids on British columns and communications, vanishing into the veld after strikes to evade counteroffensives. This approach capitalized on the vast, open expanses and sparse population, allowing Boers to maintain operational tempo despite numerical inferiority, though it was ultimately countered by British scorched-earth policies and blockhouse systems.[5][2]Weaponry and Equipment

Small Arms and Artillery

Boer commandos in the Second Anglo-Boer War (1899–1902) primarily relied on Mauser bolt-action rifles chambered in 7×57mm, including the Model 1895 and Model 1896 variants, which offered effective range exceeding 800 yards and superior accuracy that contributed to high British casualties in early engagements.[24] [25] These rifles, numbering in the tens of thousands imported by the Transvaal Republic from firms like Deutsche Waffen und Munitionsfabriken (DWM), were supplemented by older single-shot Martini-Henry rifles, Krag-Jørgensen repeaters, and a variety of hunting rifles, reflecting the commandos' civilian origins as farmers and hunters.[26] [24] Sidearms were less emphasized, with commandos often carrying revolvers such as the Colt Single Action Army or local adaptations, though melee weapons like knives were common due to the preference for marksmanship over close combat.[26] In the First Anglo-Boer War (1880–1881), small arms were more heterogeneous, featuring falling-block breech-loaders like the Westley Richards in .577/.450 caliber as the favored rifle among burghers, alongside captured or imported Martini-Henrys, which suited the shorter-range skirmishes of that conflict.[27] Ammunition shortages later in both wars forced reliance on captured British supplies, with Boers adapting 7.92mm Mauser rounds sparingly to Lee-Metford rifles when needed, though compatibility issues limited this practice.[26] Artillery support for Boer forces was limited compared to British resources but strategically deployed, with the Transvaal and Orange Free State republics fielding around 70 modern field guns at the outset of the Second War, manned by approximately 1,200 artillerymen integrated into commando operations.[28] Key pieces included four 155mm Creusot "Long Tom" siege guns, which proved devastating at sieges like Ladysmith in late 1899, four 120mm Krupp howitzers, and numerous 75mm quick-firing Creusot and Krupp field guns for mobile support.[28] Lighter rapid-fire weapons, such as 37mm Hotchkiss or Vickers-Maxim "Pom-Pom" guns, provided anti-infantry fire, with Boers employing several captured or purchased examples to harass British advances.[26] [28] In the First War, artillery was rudimentary, consisting of obsolete smoothbore ship guns and a few purpose-built pieces like 7-pounder mountain guns, which supported defensive actions but lacked the range and mobility of later acquisitions.[29] Overall, Boer artillery emphasized concealment and long-range fire, aligning with commando tactics of avoiding direct confrontation.[28]Logistical Self-Sufficiency

Boer commandos achieved logistical self-sufficiency primarily through decentralized, individual responsibility and adaptation to the veldt environment, eschewing formal supply lines in favor of mobility and opportunistic resourcing. In the guerrilla phase of the Second Anglo-Boer War (1900–1902), following the loss of conventional bases after the fall of Pretoria in June 1900, commandos operated without centralized logistics, with each burgher providing his own horse, rifle, ammunition, and initial food from personal farms.[30] This system leveraged the Boers' frontier farming and hunting backgrounds, enabling small units to sustain operations by foraging, purchasing from local populations, and raiding British convoys for essentials like maize (mealies), meat, and preserved bully beef.[31] British scorched-earth tactics, which destroyed farms and livestock to deny resources, intensified reliance on these methods, though commandos mitigated shortages by hiding crops in advance and employing "bush-lancers" to procure cattle from remote areas.[30] Horses were central to this self-reliance, with each commando member typically maintaining one or more mounts for rapid movement, foraging over vast terrains, and evading blockhouses. Boer horses, bred for endurance in harsh conditions, allowed units to cover distances quickly—up to 100 kilometers per day in some cases—while minimizing baggage trains that could hinder guerrilla tactics.[30] Ammunition and weapons followed a similar pattern: initial stocks of Mauser rifles and cartridges dwindled, prompting shifts to captured British Lee-Enfield rifles and .303 rounds obtained from ambushed patrols and supply trains, which commandos targeted to disrupt enemy logistics while replenishing their own.[30] Non-combatants, including agterryers (black servants accompanying burghers), assisted by ferrying limited supplies, tending remounts, and sourcing food, though commandos avoided slaughtering horses for meat to preserve mobility.[31] Clothing and other necessities were improvised or seized, reflecting adaptive frugality. Early prejudices against British khaki gave way to its adoption after captures from forts and convoys provided uniforms, while hides from cattle or sheep were tanned for boots and trousers when cloth wore out; canvas served as makeshift garments.[31] Basic sustenance included ground mealies roasted over open fires (using flint and steel after matches ran out), occasional potatoes, vegetables, or milk from locals, and ersatz "mealie coffee" substituting for imported goods. Salt scarcity persisted for up to ten months in some units, underscoring the limits of self-sufficiency amid prolonged attrition, yet commandos sustained irregular warfare into 1902 by prioritizing hits on British rail and wagon lines for resupply.[31][30] This approach, rooted in equestrian skill and terrain familiarity, prolonged resistance despite numerical inferiority, though it ultimately faltered against systematic British denial strategies.[30]Role in Major Conflicts

First Anglo-Boer War (1880-1881)

The Boer commandos played a pivotal role in the Transvaal Republic's successful defense against British forces during the First Anglo-Boer War, which began on December 20, 1880, following grievances over the 1877 annexation of the republic by Britain. These district-based militia units, drawn from burghers aged 16 to 60, mobilized around 7,000 mounted riflemen under Commandant-General Piet Joubert, emphasizing voluntary service without pay but relying on mandatory participation in times of crisis. Their structure allowed for rapid assembly and high mobility across the Transvaal's rugged terrain, contrasting with the more rigid British regular army formations. Commandos operated as self-sufficient groups, each led by elected field cornets and supported by local knowledge, which enabled effective scouting and ambushes rather than large-scale maneuvers.[3][32] Early engagements highlighted the commandos' ambush tactics and marksmanship superiority with modern rifles like the Martini-Henry equivalents procured from Europe. On December 20, 1880, at Bronkhorstspruit, a Transvaal commando under Commandant Frans Joubert surprised a British column of the 94th Regiment en route to Pretoria, firing from concealed positions and annihilating the force: 256 British killed or wounded, including the commander, against just one Boer death and five wounded. This victory disrupted British logistics and boosted Boer morale, prompting sieges on garrisons at Pretoria, Potchefstroom, and other outposts. Subsequent battles, such as Laing's Nek on January 28, 1881, saw commandos under Joubert repel a British frontal assault across a narrow pass, inflicting 84 British casualties while suffering 14 deaths, demonstrating defensive use of natural barriers and dispersed firing lines.[11][32] The war's decisive clash occurred at Majuba Hill on February 27, 1881, where British General George Pomeroy Colley occupied the summit expecting its defensibility, only for Boer commandos—totaling about 400 under Joubert, Nicolaas Smit, and others—to infiltrate the slopes using boulders and gullies for cover. Employing "fire and movement" tactics, the Boers advanced in small groups, outflanking exposed British positions with accurate rifle fire from elevated angles, leading to Colley's death and the surrender of 59th Regiment troops: British losses totaled 92 dead, 134 wounded, and 219 captured, versus one Boer killed and five wounded. This rout, attributed to the commandos' terrain mastery and refusal to engage in bayonet charges favored by British doctrine, compelled British commander Sir Frederick Roberts to negotiate peace. The Pretoria Convention of August 3, 1881, restored Transvaal self-governance under British suzerainty, validating the commandos' irregular warfare as a counter to imperial overreach.[33][34][35][36]Second Anglo-Boer War: Initial Conventional Engagements (1899-1900)

The Second Anglo-Boer War commenced on October 11, 1899, with Boer commandos from the South African Republic and Orange Free State invading British-held Natal and the Cape Colony the following day. In Natal, General Petrus Jacobus Joubert led approximately 12,000 to 15,000 burghers organized into commandos, advancing rapidly toward the British garrison at Dundee. This invasion aimed to seize key rail junctions and ports before significant British reinforcements arrived.[37][38] The first major engagement occurred on October 20, 1899, at the Battle of Talana Hill near Dundee, where around 4,000 Boers from five commandos occupied the hilltop with two French Creusot 75 mm field guns. British forces under Major-General William Penn Symons, numbering about 4,000 infantry and cavalry, launched a frontal assault under artillery cover, dislodging the Boers after intense fighting but suffering 241 killed and 828 wounded, including Symons who died of wounds. Boer casualties were lighter at approximately 100, highlighting the commandos' use of elevated defensive positions and modern Mauser rifles for effective long-range fire.[39][40] Subsequent clashes included the Battle of Elandslaagte on October 21, where British troops under Major-General John French recaptured the rail station from Boer forces, inflicting heavy losses through coordinated cavalry and infantry charges, though commandos withdrew in good order. On October 24, the Battle of Rietfontein saw Boer commandos under Lucas Meyer contest British advances near Ladysmith, resulting in a tactical draw with both sides holding positions amid mutual artillery exchanges. By early November, Boer forces had invested Ladysmith, initiating a siege that lasted until February 1900, while in the Cape Colony, General Piet Cronjé's commandos besieged Mafeking from October 12 and Kimberley from October 15.[38][11] The period known as "Black Week" in mid-December 1899 marked the nadir of British conventional efforts, with three successive defeats against entrenched Boer positions. On December 10 at Stormberg, General William Gatacre's 3,000 troops were ambushed by about 2,000 Boers under Adrian Grobler, losing over 600 captured due to night march errors and enfilading fire from concealed commandos. The Battle of Magersfontein on December 11 saw General Redvers Buller's relief column under Lord Methuen, some 13,000 strong, repulsed by Cronjé's 8,000-10,000 burghers entrenched along a dry riverbed, with British frontal assaults into rifle and artillery fire yielding 948 casualties against Boer losses of around 250. Finally, on December 15 at Colenso, Buller's 21,000 men attempted to cross the Tugela River against 4,000 Boers under Louis Botha, suffering 1,138 casualties including the loss of 10 guns to accurate Boer marksmanship and defensive earthworks. These victories stemmed from Boer commandos' superior marksmanship, terrain familiarity, and rapid concentration, contrasting British reliance on linear tactics suited to colonial skirmishes rather than peer adversaries armed with smokeless powder rifles.[38][11] British strategic shifts under Field Marshal Lord Roberts from February 1900 reversed Boer gains in conventional warfare. The relief of Kimberley on February 15 followed French's cavalry maneuver, culminating in the encirclement and surrender of Cronjé's 4,000 commandos at Paardeberg on February 27 after prolonged bombardment and failed breakout attempts, marking 1,100 Boer casualties and prisoners. Ladysmith was relieved on February 28, ending the Natal siege. These engagements demonstrated Boer commandos' initial success in defensive stands but vulnerability to overwhelming numbers and encirclement once British reinforcements—totaling over 400,000 by war's end—arrived, transitioning the conflict toward guerrilla operations by mid-1900.[38][37]Second Anglo-Boer War: Guerrilla Phase (1900-1902)

Following the British capture of Pretoria on June 5, 1900, and the earlier occupation of Bloemfontein in March 1900, Boer leaders decided to abandon conventional warfare in favor of guerrilla tactics to prolong the conflict and exploit British overextension. Commandos, organized into smaller, highly mobile units of 200 to 500 horsemen each, dispersed across the Transvaal and Orange Free State to conduct independent operations. Under commanders such as Christiaan de Wet in the Orange Free State and Louis Botha in the Transvaal, these units targeted British supply lines, with de Wet emerging as a master of evasion and rapid strikes.[41][37] Boer commando tactics emphasized superior marksmanship, intimate knowledge of the veldt terrain, and the use of ponies for swift movement, allowing fighters to launch ambushes on isolated convoys or railway points before melting away into the landscape. Groups avoided direct confrontations with larger British forces, instead focusing on hit-and-run raids that disrupted communications and logistics, such as derailing trains and capturing small garrisons. This approach leveraged the Boers' decentralized structure, where local farmers formed the backbone of the commandos, providing self-sufficiency in forage and intelligence from sympathetic civilians.[42][43] Notable operations included de Wet's repeated incursions and escapes from British encirclements in late 1900 and 1901, where his forces inflicted disproportionate casualties while sustaining minimal losses, and his breakthrough at Langverwacht Hill on February 23, 1902, against New Zealand troops, killing 23 and wounding 40. In the Transvaal, Botha's commandos conducted similar harassment, while Jan Smuts led a major raid into the Cape Colony in September 1901, penetrating deep into British-held territory with around 300 men before withdrawing after months of operations. These actions tied down British resources, forcing the deployment of over 200,000 troops in static defenses like blockhouses by 1901.[42][43][37] The guerrilla phase, lasting until the Peace of Vereeniging on May 31, 1902, saw Boer commandos inflict approximately 4,000 British combat deaths through such tactics, while Boer military fatalities numbered around 2,000 in this period, demonstrating the effectiveness of mobility over mass. This strategy prolonged the war by nearly two years, compelling Britain to adopt counter-guerrilla measures, though it ultimately exhausted Boer manpower and civilian support.[41][38]Notable Units and Figures

Transvaal Republic Units

The Transvaal Republic, also known as the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek (ZAR), organized its Boer forces into commandos drawn from 25 districts, with each commando comprising burghers from a specific locale who were liable for military service between ages 16 and 60.[1] By June 1899, approximately 29,279 burghers were eligible, supplemented by 800 trained artillerymen and 1,500 police.[1] The hierarchy featured elected officials: field cornets leading wards of about 60 men, commandants overseeing districts with up to 3,000 burghers in populous areas, and a commandant-general elected for five-year terms to command overall forces during war.[1] Assistant commandant-generals and combat generals handled field operations, with no formal headquarters staff, emphasizing decentralized, democratic decision-making.[12] In the First Anglo-Boer War (1880-1881), Transvaal commandos such as those from Potchefstroom and Lydenburg mobilized rapidly to repel British invasions, contributing to victories like Majuba Hill on February 27, 1881, where irregular tactics overwhelmed British regulars.[38] During the Second Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902), units played key roles in initial invasions and later guerrilla phases; for instance, the Pretoria Commando defended the capital and participated in early engagements around Natal.[44] Notable Transvaal units included:- Boksburg Commando: Credited with capturing British guns at Colenso on December 15, 1899, and the armored train incident involving Winston Churchill near Chieveley on November 15, 1899.[45]

- Carolina Commando: Mobilized on October 4, 1899, under General Schalk Burger alongside Lydenburg Commando; suffered heavy casualties at Spion Kop on January 24, 1900, with 55 of 88 men from Commandant Hendrik Prinsloo's contingent killed or wounded; later resisted British advances at Botha's Pass and Alleman's Nek after Ladysmith's relief in February 1900.[46][47][48]

- Potchefstroom Commando: Led by figures like General Piet Cronjé, engaged in sieges such as Mafeking from October 1899 and early western Transvaal defenses.[49]

- Ermelo and Heidelberg Commandos: Formed part of eastern forces blocking British entry from Natal, active in battles like Dundee on October 20, 1899.[50]