Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Limbs of the horse

View on Wikipedia

The limbs of the horse are structures made of dozens of bones, joints, muscles, tendons, and ligaments that support the weight of the equine body. They include three apparatuses: the suspensory apparatus, which carries much of the weight, prevents overextension of the joint and absorbs shock, the stay apparatus, which locks major joints in the limbs, allowing horses to remain standing while relaxed or asleep, and the reciprocal apparatus, which causes the hock to follow the motions of the stifle. The limbs play a major part in the movement of the horse, with the legs performing the functions of absorbing impact, bearing weight, and providing thrust. In general, the majority of the weight is borne by the front legs, while the rear legs provide propulsion. The hooves are also important structures, providing support, traction and shock absorption, and containing structures that provide blood flow through the lower leg. As the horse developed as a cursorial animal, with a primary defense mechanism of running over hard ground, its legs evolved to the long, sturdy, light-weight, one-toed form seen today.

Good conformation in the limbs leads to improved movement and decreased likelihood of injuries. Large differences in bone structure and size can be found in horses used for different activities, but correct conformation remains relatively similar across the spectrum. Structural defects, as well as other problems such as injuries and infections, can cause lameness, or movement at an abnormal gait. Injuries to and problems with horse legs can be relatively minor, such as stocking up, which causes swelling without lameness, or quite serious. Even leg injuries that are not immediately fatal may still be life-threatening to horses, as their bodies are adapted to bear weight on all four legs and serious problems can result if this is not possible.

Limb anatomy

[edit]

Horses are odd-toed ungulates, or members of the order Perissodactyla. This order also includes the extant species of rhinos and tapirs, and many extinct families and species. Members of this order walk on either one toe (like horses) or three toes (like rhinos and tapirs).[1] This is in contrast to even-toed ungulates, members of the order Artiodactyla, which walk on cloven hooves, or two toes. This order includes many species associated with livestock, such as sheep, goats, pigs, cows and camels, as well as species of giraffes, antelopes and deer.[2]

According to evolutionary theory, equine hooves and legs have evolved over millions of years to the form in which they are found today. The original ancestors of horses had shorter legs, terminating in five-toed feet. Over millennia, a single hard hoof evolved from the middle toe, while the other toes gradually disappeared into the tiny vestigial remnants that are found today on the lower leg bones. Prairie-dwelling equine species developed hooves and longer legs that were both sturdy and light weight to help them evade predators and cover longer distances in search of food. Forest-dwelling species retained shorter legs and three toes, which helped them on softer ground. Approximately 35 million years ago, a global drop in temperature created a major habitat change, leading to the transition of many forests to grasslands. This led to a die-out among forest-dwelling equine species, eventually leaving the long-legged, one-toed Equus of today, which includes the horse, as the sole surviving genus of the Equidae family.[3]

Legs

[edit]

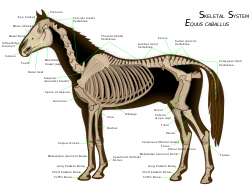

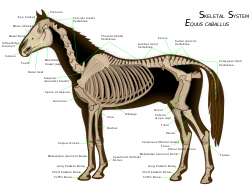

Each forelimb of the horse runs from the scapula or shoulder blade to the third phalanx (coffin or pedal) bones. In between are the humerus (arm), elbow joint, radius and ulna (forearm), carpus (knee) bones and joint, large metacarpal (cannon), small metacarpals (splints), sesamoids, fetlock joint, first phalanx (long pastern), pastern joint, second phalanx (short pastern), navicular bone, navicular bursa and coffin joint, outwardly evidenced by the coronary band (coronet).

Each hind limb of the horse runs from the pelvis to the coffin bone. After the pelvis come the femur (thigh), patella, stifle joint, tibia, fibula, tarsal (hock) bones and joints, large metatarsal (cannon) and small metatarsal (splint) bones. Below these, the arrangement of sesamoid and phalangeal bones and joints is the same as in the forelimbs.[4][5] When the horse is moving, the distal interphalangeal joint (coffin joint) has the highest amount of stresses applied to it of any joint in the body, and it can be significantly affected by trimming and shoeing techniques.[6] Although having a small range of movement, the proximal interphalangeal joint (pastern joint) is also influential to the movement of the horse, and can change the way that various shoeing techniques affect tendons and ligaments in the legs.[7] Due to the horse's development as a cursorial animal (one whose main form of movement is running), its bones evolved to facilitate speed in a forward direction over hard ground, without the need for grasping, lifting or swinging. The ulna fuses with the radius in the upper portion, and has a small portion within the radiocarpal (knee) joint, which corresponds to the wrist in humans. A similar change occurred in the fibula bone of the hind limbs. These changes were first seen in the genus Merychippus, approximately 17 million years ago.[8][9]

The major muscle groups of the forelimb include the girdle muscles, the shoulder muscles, and the forearm muscles. The girdle muscles attach the forelimb to the trunk, including the pectorals, the latissimus dorsi and the serratus muscles. The musculature of the shoulder has a stabilizing effect on the joint, which is somewhat unique in not having collateral ligaments. The major extensor of the shoulder is the biceps brachii, and the large triceps muscle extends the elbow, originating on the shoulder blade and humerus and inserting on the point of the elbow. The extensor muscles of the forelimb are relatively small compared to the flexor muscles, which assist in weightbearing and locomotion.[10]

In the hindlimb, the gluteal muscles, particularly the large middle gluteal, extend the hip, driving the limb backwards. Extension of the stifle is achieved through the movement of the quadriceps group of muscles on the front of the femur, while the muscles at the back of the hindquarters, called the hamstring group, provide forward motion of the body and rearward extension of the hind limbs. Extension of the hock is achieved by the Achilles tendon, located above the hock.[11]

The fetlock joint is supported by a group of lower leg ligaments known as the suspensory apparatus.[12] This apparatus carries much of the weight of the horse, both when standing and while moving, and prevents the fetlock joint from hyperextending, especially when the joint is bearing weight. During movement, the apparatus stores and releases energy in the manner of a spring: stretching while the joint is extended and contracting (and thus releasing energy) when the joint flexes.[13] This ability to use stored energy makes horses' gaits more efficient than other large animals, including cattle.[14] The suspensory apparatus consists of the suspensory ligament, the sesamoid bones, and the distal sesamoidean ligaments.[10]

Horses use a group of ligaments, tendons and muscles known as the stay apparatus to "lock" major joints in the limbs, allowing them to remain standing while relaxed or asleep. The lower part of the stay apparatus consists of the suspensory apparatus, which is the same in both sets of limbs, while the upper portion differs between the fore and hind limbs. The upper portion of the stay apparatus in the forelimbs consists of the lacertus fibrosus, an extension of the biceps brachii muscle, as well as contributions from the accessory ligament of the deep digital flexor tendon ("check ligament"). The upper portion in the hind limbs consists primarily of the reciprocal apparatus of the hock and stifle, with the ability to lock the stifle in extension via a shelf on the femur where the patella can lodge, making a loop with the middle and medial patellar ligamnets.[11]

Hoof

[edit]

The hoof of the horse contains over a dozen different structures, including bones, cartilage, tendons and tissues. The coffin or pedal bone is the major hoof bone, supporting the majority of the weight. Behind the coffin bone is the navicular bone, itself cushioned by the navicular bursa, a fluid-filled sac.

The digital cushion is a blood vessel-filled structure located in the rear of the hoof, which assists with blood flow throughout the leg. At the top of the hoof wall is the corium, tissue which continually produces the horn of the outer hoof wall, which is in turn protected by the periople, a thin outer layer which prevents the interior structures from drying out. The wall is connected to the coffin bone by laminar attachments, a flexible layer which helps to suspend and protect the coffin bone.

The main tendon in the hoof is the deep digital flexor tendon, which connects to the bottom of the coffin bone. The impact zone on the bottom of the hoof includes the sole, which has an outer, insensitive layer and a sensitive inner layer, and the frog, which lies between the heels and assists in shock absorption and blood flow.

The final structures are the lateral cartilages, connected to the upper coffin bone, which act as the flexible heels, allowing hoof expansion. These structures allow the hoof to perform many functions. It acts as a support and traction point, shock absorber and system for pumping blood back through the lower limb.[15]

Remnants of the "lost" digits of the horse are theorized to be found on the hoof.[16]

Movement

[edit]

A sequence of movements in which a horse takes a step with all four legs is called a stride. During each step, with each leg, a horse completes four movements: the swing phase, the grounding or impact, the support period (stance phase) and the thrust. While the horse uses muscles throughout its body to move, the legs perform the functions of absorbing impact, bearing weight, and providing thrust.[17] Good movement is sound, symmetrical, straight, free and coordinated, all of which depend on many factors, including conformation, soundness, care and training of the horse, and terrain and footing. The proportions and length of the bones and muscles in the legs can significantly impact the way an individual horse moves. The angles of certain bones, especially in the hind leg, shoulders, and pasterns, also affect movement.[18]

The forelegs carry the majority of the weight, usually around 60 percent, with exact percentages depending on speed, conformation, and gait. Movement adds concussive force to weight, increasing the likelihood that poor conformation can exaggerate forces within the limb, potentially leading to injury.[19][20] At different points in the gallop, all weight is resting on one front hoof, then all on one rear hoof.[20][21] In the sport of dressage, horses are encouraged to shift their weight more to their hindquarters, which enables lightness of the forehand and increased collection.[22] While the forelimbs carry the weight the hind limbs provide propulsion, due to the angle between the stifle and hock. This angle allows the hind legs to flex as weight is applied during the stride, then release as a spring to create forward or upward movement. The propulsion is then transmitted to the forehand through the structures of the back, where the forehand then acts to control speed, balance and turning.[23] The range of motion and propulsion power in horses varies significantly, based on the placement of muscle attachment to bone. The muscles are attached to bone relatively high in the body, which results in small differences in attachment making large differences in movement. A change of .5 inches (1.3 cm) in muscle attachment can affect range of motion by 3.5 inches (8.9 cm) and propulsion power by 20 percent.[24]

"Form to function" is a term used in the equestrian world to mean that the "correct" form or structure of a horse is determined by the function for which it will be used. The legs of a horse used for cutting, in which quick starts, stops and turns are required, will be shorter and more thickly built than those of a Thoroughbred racehorse, where forward speed is most important. However, despite the differences in bone structure needed for various uses, correct conformation of the leg remains relatively similar.[20]

Structural defects

[edit]The ideal horse has legs which are straight, correctly set and symmetrical. Correct angles of major bones, clean, well-developed joints and tendons, and well-shaped, properly-proportioned hooves are also necessary for ideal conformation.[25] "No legs, no horse"[20] and "no hoof, no horse"[26] are common sayings in the equine world. Individual horses may have structural defects, some of which lead to poor movement or lameness. Although certain defects and blemishes may not directly cause lameness, they can often put stress on other parts of the body, which can then cause lameness or injuries.[25] Poor conformation and structural defects do not always cause lameness, however, as was shown by the champion racehorse Seabiscuit, who was considered undersized and knobby-kneed for a Thoroughbred.[19]

Common defects of the forelegs include base-wide and base-narrow, where the legs are farther apart or closer together on the ground then they are when they originate in the chest; toeing-in and toeing-out, where the hooves point inwards or outwards; knee deviations to the front (buck knees), rear (calf knees), inside (knock knees) or outside (bowleg); short or long pasterns; and many problems with the feet. Common defects of the hind limbs include the same base-wide and base-narrow stances and problems with the feet as the fore limbs, as well as multiple issues with the angle formed by the hock joint being too angled (sickle-hocked), too straight (straight behind) or having an inward deviation (cow-hocked).[19] Feral horses are seldom found with serious conformation problems in the leg, as foals with these defects are generally easy prey for predators. Foals raised by humans have a better chance for survival, as there are therapeutic treatments that can improve even major conformation problems. However, some of these conformation problems can be transmitted to offspring, and so these horses are a poor choice for breeding stock.[20]

Lameness and injuries

[edit]

Lameness in horses is movement at an abnormal gait due to pain in any part of the body. It is most commonly caused by pain to the legs or feet. Lameness can also be caused by abnormalities in the nervous system. While horses with poor conformation and congenital conditions are more likely to develop lameness, trauma, infection and acquired abnormalities are also causes. The largest cause of poor performance in equine athletes is lameness caused by abnormalities in the muscular or skeletal systems. The majority of lameness is found in the forelimbs, with at least 95 percent of these cases stemming from problems in the structures from the knee down. Lameness in the hind limbs is caused by problems in the hock and/or stifle 80 percent of the time.[27]

There are numerous issues that can occur with horses' legs that may not necessarily cause lameness. Stocking up is an issue that occurs in horses that are held in stalls for multiple days after periods of activity. Fluid collects in the lower legs, producing swelling and often stiffness. Although it does not usually cause lameness or other problems, prolonged periods of stocking up can lead to other skin issues. Older horses and horse with heavy muscling are more prone to this condition.[28] A shoe boil is an injury that occurs when there is trauma to the bursal sac of the elbow, causing inflammation and swelling. Multiple occurrences can cause a cosmetic sore and scar tissue, called a capped elbow, or infections. Shoe boils generally occur when a horse hits its elbow with a hoof or shoe when lying down.[29] Windpuffs, or swelling to the back of the fetlock caused by inflammation of the sheaths of the deep digital flexor tendon, appear most often in the rear legs. Soft and fluid-filled, the swelling may initially be accompanied by heat and pain, but can remain long after the initial injury has healed without accompanying lameness. Repeated injuries to the tendon sheath, often caused by excessive training or work on hard surfaces, can cause larger problems and lameness.[30]

Leg injuries that are not immediately fatal still may be life-threatening because a horse's weight must be distributed on all four legs to prevent circulatory problems, laminitis, and other infections. If a horse loses the use of one leg temporarily, there is the risk that other legs will break down during the recovery period because they are carrying an abnormal weight load. While horses periodically lie down for brief periods of time, a horse cannot remain lying in the equivalent of a human's "bed rest" because of the risk of developing sores, internal damage, and congestion.[31]

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Introduction to the Perissodactyla". University of California Museum of Paleontology. Retrieved January 15, 2013.

- ^ "Introduction to the Artiodactyla". University of California Museum of Paleontology. Retrieved January 15, 2013.

- ^ "On Your Toes". American Museum of Natural History. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- ^ Harris, p. 226.

- ^ Giffin and Gore, pp. 262–263

- ^ Denoix, J. M. (1999). "Functional Anatomy of the Equine Interphalangeal Joints" (PDF). AAEP Proceedings. 45. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved June 1, 2013.

- ^ Lawson, Sian E. M.; Chateau, Henry; Pourcelot, Philippe; Denoix, Jean-Marie; Crevier-Denoix, Nathalie (May 2007). "Effect of toe and heel elevation on calculated tendon strains in the horse and the influence of the proximal interphalangeal joint". Journal of Anatomy. 210 (5): 583–591. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2007.00714.x. PMC 2375746. PMID 17451533.

- ^ Rooney, James R. (1998). The Lame Horse. The Russell Meerdink Company Ltd. pp. 9–10. ISBN 978-0-929346-55-7.

- ^ Hunt, Kathleen. "Horse Evolution" (PDF). Carnegie Mellon University. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 5, 2013. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- ^ a b Singh, Baljit (2017). "The forelimb of the horse". Dyce, Sack and Wensing's Textbook of Veterinary Anatomy, (5th ed.). St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier, Inc. pp. 574–605. ISBN 978-0-323442640.

- ^ a b Singh, Baljit (2017). "The hindlimb of the horse". Dyce, Sack and Wensing's Textbook of Veterinary Anatomy, (5th ed.). St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier, Inc. pp. 612–631. ISBN 978-0-323442640.

- ^ Harris, p. 251.

- ^ Ferraro, Gregory L.; Stover, Susan M.; Whitcomb, Mary Beth. "Suspensory Ligament Injuries in Horses" (PDF). Davis: University of California. pp. 6–7. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 31, 2009. Retrieved September 16, 2013.

- ^ Larson, Erica (July 16, 2012). "Horses' Physiologic Responses to Exercise". The Horse.

- ^ Harris, pp. 254–256.

- ^ Solounias, Nikos; Danowitz, Melinda; Stachtiaris, Elizabeth; Khurana, Abhilasha; Araim, Marwan; Sayegh, Marc; Natale, Jessica (2018). "The evolution and anatomy of the horse manus with an emphasis on digit reduction". Royal Society Open Science. 5 (1) 171782. doi:10.1098/rsos.171782. PMC 5792948. PMID 29410871.

- ^ Harris, pp. 256–258.

- ^ Harris, pp. 260–264.

- ^ a b c Oke, Stacey (October 1, 2010). "Horse Conformation Conundrums". The Horse. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Sellnow, Les (July 1, 1999). "Leg Conformation". The Horse. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ Hansen, D. Karen; Schafer, Stephen R. (2007). "Horse Gaits" (Powerpoint). University of Nevada, Reno. Retrieved September 17, 2013.

- ^ "Half Halt" (PDF). United States Dressage Federation. Retrieved September 17, 2013.

- ^ Clayton, Hilary (October 2007). "Components of Collection" (PDF). Dressage Today. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 13, 2013. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- ^ "Movement and Conformational Unsoundness" (PDF). Middle California Region - United States Pony Clubs. p. 1. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- ^ a b Harris, pp. 265–266.

- ^ "No Hoof, No Horse". The Horse. May 13, 2009. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ Oke, Stacey (2012). "Lameness in Horses" (PDF). Blood Horse Publications. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ King, Marcia (July 1, 2007). "All Stocked Up". The Horse. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ^ Loving, Nancy S. (March 6, 2008). "Shoe Boils". HorseChannel. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ^ Smith Thomas, Heather (March 1, 2009). "Windpuffs in Horses". The Horse. Retrieved May 31, 2013.

- ^ Grady, Denise (May 23, 2006). "State of the Art to Save Barbaro". The New York Times. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

References

[edit]- Giffin, James M.; Gore, Tom (1998). Horse Owner's Veterinary Handbook (Second ed.). Howell Book House. ISBN 978-0-87605-606-6.

- Harris, Susan E. (1996). The United States Pony Club Manual of Horsemanship: Advanced Horsemanship – B, HA, A Levels. Howell Book House. ISBN 978-0-87605-981-4.