Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Tapir

View on Wikipedia

| Tapir Temporal range: Early Oligocene[1] – Recent

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Tapir species, from top left clockwise: South American tapir (Tapirus terrestris), mountain tapir (Tapirus pinchaque), Malayan tapir (Tapirus indicus) and Baird's tapir (Tapirus bairdii) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Clade: | Tapiromorpha |

| Suborder: | Ceratomorpha |

| Superfamily: | Tapiroidea |

| Family: | Tapiridae Gray, 1821[2][3] |

| Type genus | |

| Tapirus Brisson, 1762

| |

| Genera[7] | |

|

About 15

| |

| |

Distribution of extant species

| |

| Synonyms[3] | |

| |

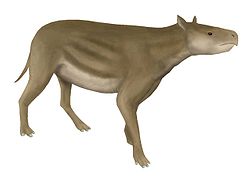

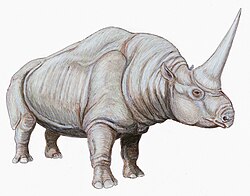

Tapirs (/ˈteɪpər/ TAY-pər)[8][9] are large, herbivorous mammals belonging to the family Tapiridae.[3] They are similar in shape to a pig, with a short, prehensile nose trunk (proboscis). Tapirs inhabit jungle and forest regions of South and Central America and Southeast Asia. They are one of three extant branches of Perissodactyla (odd-toed ungulates), alongside equines and rhinoceroses. Only a single genus, Tapirus, is currently extant. Tapirs migrated into South America during the Pleistocene epoch from North America after the formation of the Isthmus of Panama as part of the Great American Interchange.[10] Tapirs were present across North America, but became extinct in the region at the end of the Late Pleistocene, around 12,000 years ago.

Name

[edit]The term tapir comes from the Portuguese-language words tapir, tapira, which themselves trace their origins back to Old Tupi, specifically the term tapi'ira.[11] This word, according to Eduardo de Almeida Navarro, referred in a more precise manner to the species Tapirus terrestris.[12]

Species

[edit]There are four widely recognized extant species of tapir, all in the genus Tapirus of the family Tapiridae. They are the South American tapir, the Malayan tapir, Baird's tapir, and the mountain tapir. In 2013, a group of researchers said they had identified a fifth species of tapir, the kabomani tapir. However, the existence of the kabomani tapir as a distinct species has been widely disputed, and recent genetic evidence further suggests that it actually is part of the species South American tapir.[13][14]

Extant species

[edit]| Photo | Common name | Scientific name | Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Baird's tapir (also called the Central American tapir) | Tapirus bairdii (Gill, 1865) | Mexico, Central America and northwestern South America |

|

South American tapir (also called the Brazilian tapir or lowland tapir) | Tapirus terrestris (Linnaeus, 1758) | Venezuela, Colombia, and the Guianas in the north to Brazil, Argentina, and Paraguay in the south, to Bolivia, Peru, and Ecuador in the West. |

|

Mountain tapir (also called the woolly tapir) | Tapirus pinchaque (Roulin, 1829) | Eastern and Central Cordilleras mountains in Colombia, Ecuador, and the far north of Peru. |

|

Malayan tapir (also called the Asian tapir, Oriental tapir or Indian tapir) | Tapirus indicus (Desmarest, 1819) | Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, and Thailand |

The four species are all classified on the IUCN Red List as either Endangered or Vulnerable. The tapirs have a number of extinct relatives in the superfamily Tapiroidea. The closest extant relatives of the tapirs are the other odd-toed ungulates, which include horses, wild asses, zebras and rhinoceroses.

Extinct species

[edit]During the Late Pleistocene, several other species inhabited North America, including Tapirus veroensis, native to the southern and eastern United States (with its northernmost records being New York State), and Tapirus merriami and Tapirus californicus, native to Western North America. These became extinct during the Quaternary extinction event around 12,000 years ago, along with most of the other large mammals of the Americas, co-inciding with the first arrival of humans to the continent.[15] Tapirus augustus (formerly placed in Megatapirus), native to Southeast and East Asia, substantially larger than the Malayan tapir, also became extinct at some point during the Late Pleistocene.[16] Many primitive tapirs were originally classified under Palaeotapirus including members of Paratapirus and Plesiotapirus,[17] but the original diagnostic material of the genus was too poor to characterize, leading to included species being moved to new genera.[18]

| Image | Species |

|---|---|

| |

M. harrisonensis |

|

N. robustus |

|

P. intermedius |

|

P. yagii |

|

P. simplex |

|

| |

Giant tapir (T. augustus) Cope's tapir (T. haysii) T. veroensis |

|

General appearance

[edit]Size varies between types, but most tapirs are about 2 m (6+1⁄2 ft) long, stand about 1 m (3+1⁄4 ft) high at the shoulder, and weigh between 150 and 300 kg (330 and 660 lb). Their coats are short and range in colour from reddish brown, to grey, to nearly black, with the notable exceptions of the Malayan tapir, which has a white, saddle-shaped marking on its back, and the mountain tapir, which has longer, woolly fur. All tapirs have oval, white-tipped ears, rounded, protruding rumps with stubby tails, and splayed, hooved toes, with four toes on the front feet and three on the hind feet, which help them to walk on muddy and soft ground. Baby tapirs of all types have striped-and-spotted coats for camouflage.[citation needed]

Females have a single pair of mammary glands,[19] and males have long penises relative to their body size.[20][21][22][23][24]

Physical characteristics

[edit]

The proboscis of the tapir is a highly flexible organ, able to move in all directions, allowing the animals to grab foliage that would otherwise be out of reach. Tapirs often exhibit the flehmen response, a posture in which they raise their snouts and show their teeth to detect scents. This response is frequently exhibited by bulls sniffing for signs of other males or females in oestrus in the area. The length of the proboscis varies among species; Malayan tapirs have the longest snouts and Brazilian tapirs have the shortest.[25] The evolution of tapir probosces, made up almost entirely of soft tissues rather than bony internal structures, gives the Tapiridae skull a unique form in comparison to other perissodactyls, with a larger sagittal crest, orbits positioned more rostrally, a posteriorly telescoped cranium, and a more elongated and retracted nasoincisive incisure.[25][26]

-

Malayan tapir skull

-

Baird's tapir skull

-

South American tapir skull

-

Mountain tapir skull

Tapirs have brachyodont, or low-crowned teeth, that lack cementum. Their dental formula is:

| Dentition |

|---|

| 3.1.4.3 |

| 3.1.3–4.3 |

Totaling 42 to 44 teeth, this dentition is closer to that of equids, which may differ by one less canine, than their other perissodactyl relatives, rhinoceroses.[27][28] Their incisors are chisel-shaped, with the third large, conical upper incisor separated by a short gap from the considerably smaller canine. A much longer gap is found between the canines and premolars, the first of which may be absent.[29] Tapirs are lophodonts, and their cheek teeth have distinct lophs (ridges) between protocones, paracones, metacones and hypocones.[30][31]

Tapirs have brown eyes, often with a bluish cast to them, which has been identified as corneal cloudiness, a condition most commonly found in Malayan tapirs. The exact etiology is unknown, but the cloudiness may be caused by excessive exposure to light or by trauma.[32][33] However, the tapir's sensitive ears and strong sense of smell help to compensate for deficiencies in vision.

Tapirs have simple stomachs and are hindgut fermenters that ferment digested food in a large cecum.[34]

Life cycle

[edit]Young tapirs reach sexual maturity between three and five years of age, with females maturing earlier than males.[35] Under good conditions, a healthy female tapir can reproduce every two years; a single young, called a calf, is born after a gestation of about 13 months.[36] The natural lifespan of a tapir is about 25 to 30 years, both in the wild and in zoos.[37] Apart from mothers and their young offspring, tapirs lead almost exclusively solitary lives.

Behaviour

[edit]Although they frequently live in dryland forests, tapirs with access to rivers spend a good deal of time in and under water, feeding on soft vegetation, taking refuge from predators, and cooling off during hot periods. Tapirs near a water source will swim, sink to the bottom, and walk along the riverbed to feed, and have been known to submerge themselves to allow small fish to pick parasites off their bulky bodies.[37] Along with freshwater lounging, tapirs often wallow in mud pits, which helps to keep them cool and free of insects.

In the wild, the tapir's diet consists of fruit, berries, and leaves, particularly young, tender vegetation. Tapirs will spend many of their waking hours foraging along well-worn trails, snouts to the ground in search of food. Baird's tapirs have been observed to eat around 40 kg (85 lb) of vegetation in one day.[38]

Tapirs are largely nocturnal and crepuscular, although the smaller mountain tapir of the Andes is generally more active during the day than its congeners. They have monocular vision.

Copulation may occur in or out of water. In captivity, mating pairs will often copulate several times during oestrus.[19][39] Intromission lasts between 10 and 20 minutes.[40]

-

An adult Malayan tapir sitting

-

Adult Malayan tapir exhibiting the flehmen response

-

The undersides of the front feet (left, with four toes) and back feet (right, with three toes) of a Malayan tapir at rest

-

A baby South American tapir, with spots and stripes characteristic of all juvenile tapirs

-

Tooth from the extinct Tapirus veroensis, 2.5 cm (1 in) wide, about 1 million years old, alluvial deposits, Florida, US

Habitat, predation, and vulnerability

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2022) |

Adult tapirs are large enough to have few natural predators, and the thick skin on the backs of their necks helps to protect them from threats such as jaguars, crocodiles, anacondas, and tigers. The creatures are also able to run fairly quickly, considering their size and cumbersome appearance, finding shelter in the thick undergrowth of the forest or in water. Hunting for meat and hides has substantially reduced their numbers and, more recently, habitat loss has resulted in the conservation watch-listing of all four species; the Brazilian tapir is classified as vulnerable, and Baird's tapir, the mountain tapir, and the Malayan tapir are endangered. According to 2022 study published in the Neotropical Biology and Conservation, the lowland tapir in the Atlantic Forest is at risk of complete extinction as a result of anthropogenic pressures, in particular hunting, deforestation and population isolation.[41][42][43]

Evolution and natural history

[edit]

Tapirs originated from the "tapiroids", a group of primitive perissodactyls that inhabited North America and Asia during the Eocene epoch, with tapirs probably originating from the family Helaletidae.[44][45] The oldest known members of the family Tapiridae such as Protapirus are known from the Early Oligocene of Europe.[45] The oldest representatives of the modern genus Tapirus appeared in Europe during the Mid-Miocene, with Tapirus dispersing into Asia and North America by the late Miocene.[10][46] The last species of tapir native to Europe, Tapirus arvernensis, became extinct around the end of the Pliocene, approximately 2.6 million years ago.[46][47] Tapirs dispersed into South America during Pleistocene as part of the Great American Biotic Interchange with their oldest records on the continent dating to around 2.6-1 million years ago.[10]

Approximate divergence times based on a 2013 analysis of mtDNA sequences are 0.5 Ma for T. kabomani and the T. terrestris–T. pinchaque clade, 5 Ma for T. bairdii and the three South American tapirs, and 9 Ma for the branching of T. indicus.[48] T. pinchaque arises from within a paraphyletic complex of T. terrestris populations.[48]

| Tapirus |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Genetics

[edit]

The species of tapir have the following chromosomal numbers:

| Malayan tapir, T. indicus | 2n = 52 |

|---|---|

| Mountain tapir, T. pinchaque | 2n = 76 |

| Baird's tapir, T. bairdii | 2n = 80 |

| South American tapir, T. terrestris | 2n = 80 |

The Malayan tapir, the species most isolated geographically and genetically, has a significantly smaller number of chromosomes and has been found to share fewer homologies with the three types of American tapirs. A number of conserved autosomes (13 between karyotypes of Baird's tapir and the South American tapir, and 15 between Baird's and the mountain tapir) have also been found in the American species that are not found in the Asian animal. However, geographic proximity is not an absolute predictor of genetic similarity; for instance, G-banded preparations have revealed Malayan, Baird's and South American tapirs have identical X chromosomes, while mountain tapirs are separated by a heterochromatic addition/deletion.[49]

Lack of genetic diversity in tapir populations has become a major source of concern for conservationists. Habitat loss has isolated already small populations of wild tapirs, putting each group in greater danger of dying out completely. Even in zoos, genetic diversity is limited; all captive mountain tapirs, for example, are descended from only two founder individuals.[50]

Hybrids of Baird's and the South American tapirs were bred at the San Francisco Zoo around 1969 and later produced a backcross second generation.[51]

Conservation

[edit]A number of conservation projects have been started around the world. The Tapir Specialist Group, a unit of the IUCN Species Survival Commission, strives to conserve biological diversity by stimulating, developing, and conducting practical programs to study, save, restore, and manage the four species of tapir and their remaining habitats in Central and South America and Southeast Asia.[52]

The Baird's Tapir Project of Costa Rica, begun in 1994, is the longest ongoing tapir project in the world. It involves placing radio collars on tapirs in Costa Rica's Corcovado National Park to study their social systems and habitat preferences.[53]

The Lowland Lowland Tapir Conservation Initiative is a conservation and research organization founded by Patrícia Medici, focused on tapir conservation in Brazil.

Attacks on humans

[edit]Tapirs are generally shy, but when scared they can defend themselves with their very powerful jaws. In 1998, a zookeeper in Oklahoma City was mauled and had an arm severed after opening the door to a female tapir's enclosure to push food inside (the tapir's two-month-old baby also occupied the cage at the time).[54] In 2006, Carlos Manuel Rodriguez Echandi (who was then the Costa Rican Environmental Minister) became lost in the Corcovado National Park and was found by a search party with a "nasty bite" from a wild tapir.[55] In 2013, a two-year-old girl suffered stomach and arm injuries after being mauled by a South American tapir in Dublin Zoo during a supervised experience in the tapir enclosure. Dublin Zoo pleaded guilty to breaching health and safety regulations and was ordered to pay €5,000 to charity.[56] However, such examples are rare; for the most part, tapirs are likely to avoid confrontation in favour of running from predators, hiding, or, if possible, submerging themselves in nearby water until a threat is gone.[57]

Frank Buck wrote about an attack by a tapir in 1926, which he described in his book, Bring 'Em Back Alive.[58]

Folklore

[edit]Tapirs feature in the folklore of several cultures around the world. In Japan, tapirs are associated with the mythological Baku, believed to ward off nightmares. In South America, tapirs are associated with the creation of the earth.[59]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Protapirus". Paleobiology Database. Retrieved 2021-04-20.

- ^ Gray, J.E. (1821). "On the natural arrangement of vertebrose animals". The London Medical Repository Monthly Journal and Review. 15: 296–310.

- ^ a b c Grubb, P. (2005). "Order Perissodactyla". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 633. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ "Teleolophus". Paleobiology Database. Retrieved 2023-04-20.

- ^ a b Grubb, P. (2005). "Order Perissodactyla". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 633. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b c Hulbert, R.C. (2010). "A new early Pleistocene tapir (Mammalia: Perissodactyla) from Florida, with a review of Blancan tapirs from the state" (PDF). Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History. 49 (3): 67–126. doi:10.58782/flmnh.ezjr9001.

- ^ "Tapiridae". Global Biodiversity Information Facility. Retrieved 2021-11-08.

- ^ "Definition of tapir". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

- ^ "Collins Dictionary". Retrieved 18 June 2024.

- ^ a b c Holanda, Elizete Celestino; Ferrero, Brenda Soledad (March 2013). "Reappraisal of the Genus Tapirus (Perissodactyla, Tapiridae): Systematics and Phylogenetic Affinities of the South American Tapirs". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 20 (1): 33–44. doi:10.1007/s10914-012-9196-z. hdl:11336/18792. S2CID 15780542.

- ^ "Tapir Definition & Meaning". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 29 September 2024.

- ^ Navarro, Eduardo de Almeida (2013). Dicionário de tupi antigo: a língua indígena clássica do Brasil (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Global. pp. 462–463. ISBN 978-85-260-1933-1.

- ^ Ruiz-García, Manuel; Castellanos, Armando; Bernal, Luz Agueda; Pinedo-Castro, Myreya; Kaston, Franz; Shostell, Joseph M. (2016-03-01). "Mitogenomics of the mountain tapir (Tapirus pinchaque, Tapiridae, Perissodactyla, Mammalia) in Colombia and Ecuador: Phylogeography and insights into the origin and systematics of the South American tapirs". Mammalian Biology. 81 (2): 163–175. Bibcode:2016MamBi..81..163R. doi:10.1016/j.mambio.2015.11.001.

- ^ "All About the Terrific Tapir". Tapir Specialist Group. Retrieved 2018-12-01.

- ^ Graham, Russell W.; Grady, Frederick; Ryan, Timothy M. (2019-10-01). "Juvenile Pleistocene tapir skull from Russells Reserve Cave, Bath County, Virginia: Implications for cold climate adaptations". Quaternary International. Late Quaternary Environments: landscapes, biota, humans. 530–531: 35–41. Bibcode:2019QuInt.530...35G. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2018.06.021. ISSN 1040-6182. S2CID 135105320.

- ^ Fan, Yaobin; Shao, Qingfeng; Bacon, Anne-Marie; Liao, Wei; Wang, Wei (2022-10-15). "Late Pleistocene large-bodied mammalian fauna from Mocun cave in south China: Palaeontological, chronological and biogeographical implications". Quaternary Science Reviews. 294 107741. Bibcode:2022QSRv..29407741F. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2022.107741. S2CID 252487193.

- ^ Fortelius, Mikael (2013). Fossil Mammals of Asia: Neogene Biostratigraphy and Chronology. Columbia University Press. pp. 317–318. ISBN 978-0-231-15012-5.

- ^ Cerdeño, E.; Ginsburg, L. (1988). "European Oligocene and early Miocene Tapiridae (Perissodactyla, Mammalia)". Annales de Paléontologie. 74 (2): 71–96.

- ^ a b Gorog, A. (2001). Tapirus terrestris, Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved June 19, 2006.

- ^ Hickey, R.S. Georgina (1997). "Tapir Penis". Nature Australia. 25 (8): 10–11.

- ^ Endangered Wildlife and Plants of the World. Marshall Cavendish. 2001. pp. 1460–. ISBN 978-0-7614-7194-3.

- ^ Prasad, M. R. N. (1974). Männliche Geschlechtsorgane. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 119–. ISBN 978-3-11-004974-9.

- ^ Gade, Daniel W. (1999). Nature & Culture in the Andes. University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 125–. ISBN 978-0-299-16124-8.

- ^ Quilter, Jeffrey (2004). Cobble Circles and Standing Stones: Archaeology at the Rivas Site, Costa Rica. University of Iowa Press. pp. 181–. ISBN 978-1-58729-484-6.

- ^ a b Witmer, Lawrence; Sampson, Scott D.; Solounias, Nikos (1999). "The proboscis of tapirs (Mammalia: Perissodactyla): a case study in novel narial anatomy" (PDF). Journal of Zoology. 249 (3): 251. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1999.tb00763.x.

- ^ Colbert, Matthew (2002) Tapirus terrestris. Digital Morphology. Retrieved June 20, 2006.

- ^ Ballenger, L. and P. Myers. 2001. "Tapiridae" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved June 20, 2006.

- ^ Huffman, Brent. Order Perissodactyla at Ultimate Ungulate

- ^ "Lydekker, Richard (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 169–171.

- ^ Myers, P., R. Espinosa, C. S. Parr, T. Jones, G. S. Hammond, and T. A. Dewey. 2006. The Diversity of Cheek Teeth. The Animal Diversity Web (online). Retrieved June 20, 2006.

- ^ Myers, P., R. Espinosa, C. S. Parr, T. Jones, G. S. Hammond, and T. A. Dewey. 2006. The Basic Structure of Cheek Teeth. The Animal Diversity Web (online). Retrieved June 20, 2006.

- ^ Tapirs Described, the Tapir Gallery

- ^ Janssen, Donald L., DVM, Dipl ACZM, Bruce A. Rideout, DVM, PhD, Dipl ACVP, Mark E. Edwards, PhD. "Medical Management of Captive Tapirs (Tapirus sp.)." 1996 American Association of Zoo Veterinarians Proceedings. Nov 1996. Puerto Vallarta, Mexico. Pp. 1–11

- ^ Eisenberg, J.F.; et al. (1990). "Tapirs". In Parker, S.P. (ed.). Grzimek's Encyclopedia of Mammals, Vol. 4. New York: McGraw-Hill Publishing. pp. 598–620. ISBN 978-0-07-909508-4.

- ^ "Woodland Park Zoo Animal Fact Sheet: Malayan Tapir (Tapirus indicus)". Zoo.org. Archived from the original on 2006-08-29. Retrieved 2009-11-02.

- ^ Tapir | San Diego Zoo Animals.

- ^ a b Morris, Dale (March 2005). "Face to face with big nose." Archived 2006-05-06 at the Wayback Machine BBC Wildlife. pp. 36–37.

- ^ TPF News, Tapir Preservation Fund, Vol. 4, No. 7, July 2001. See section on study by Charles Foerster.

- ^ "Minimum Husbandry Standards: Tapiridae (tapirs)". Archived from the original on 2016-04-16. Retrieved 2009-11-02.

- ^ Bell, Catharine E. (2001). Encyclopedia of the World's Zoos. Taylor & Francis. pp. 1205–. ISBN 978-1-57958-174-9.

- ^ O'Connell-Domenech, Alejandra (January 17, 2022). "Atlantic Forest tapir at risk of complete extinction, scientists say". The Hill. Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- ^ Cockburn, Harry (January 17, 2022). "Lowland tapirs at increasing risk of extinction, scientists warn". The Independent. Archived from the original on 2022-05-26. Retrieved January 25, 2022.

- ^ Flesher, Kevin M.; Medici, Emília Patrícia (2022). "The distribution and conservation status of Tapirus terrestris in the South American Atlantic Forest". Neotropical Biology and Conservation. 17 (1): 1–19. doi:10.3897/neotropical.17.e71867. S2CID 245870543.

- ^ Bai, Bin; Meng, Jin; Mao, Fang-Yuan; Zhang, Zhao-Qun; Wang, Yuan-Qing (2019-11-08). Smith, Thierry (ed.). "A new early Eocene deperetellid tapiroid illuminates the origin of Deperetellidae and the pattern of premolar molarization in Perissodactyla". PLOS One. 14 (11) e0225045. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1425045B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0225045. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 6839866. PMID 31703104.

- ^ a b Scherler, Laureline; Becker, Damien; Berger, Jean-Pierre (2011-03-17). "Tapiridae (Perissodactyla, Mammalia) of the Swiss Molasse Basin during the Oligocene–Miocene transition". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 31 (2): 479–496. Bibcode:2011JVPal..31..479S. doi:10.1080/02724634.2011.550360. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 73527662.

- ^ a b Made, Jan van der; Stefanovic, Ivan (2006-06-21). "A small tapir from the Turolian of Kreka (Bosnia) and a discussion on the biogeography and stratigraphy of the Neogene tapirs". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Abhandlungen. 240 (2): 207–240. doi:10.1127/njgpa/240/2006/207. ISSN 0077-7749.

- ^ Cirilli, Omar; Pandolfi, Luca; Bernor, Raymond L. (December 2020). "The Villafranchian perissodactyls of Italy: knowledge of the fossil record and future research perspectives". Geobios. 63: 1–21. Bibcode:2020Geobi..63....1C. doi:10.1016/j.geobios.2020.09.001. S2CID 228974817.

- ^ a b Cozzuol, M. A.; Clozato, C. L.; Holanda, E. C.; Rodrigues, F. V. H. G.; Nienow, S.; De Thoisy, B.; Redondo, R. A. F.; Santos, F. C. R. (2013). "A new species of tapir from the Amazon". Journal of Mammalogy. 94 (6): 1331–1345. doi:10.1644/12-MAMM-A-169.1.

- ^ Houck, M.L.; Kingswood, S.C.; Kumamoto, A.T. (2000). "Comparative cytogenetics of tapirs, genus Tapirus (Perissodactyla, Tapiridae)". Cytogenetics and Cell Genetics. 89 (1–2): 110–115. doi:10.1159/000015587. PMID 10894950. S2CID 21583683.

- ^ Mountain Tapir Conservation at the Cheyenne Mountain Zoo Archived June 15, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Pictures of T. bairdii x T. terrestris cross taken by Sheryl Todd, The Tapir Gallery, web site of the Tapir Preservation Fund

- ^ "About the Tapir Specialist Group". Tapirs.org. Archived from the original on 2009-01-25. Retrieved 2009-11-02.

- ^ "Baird's Tapir Project of Costa Rica". Savetapirs.org. 2009-02-18. Archived from the original on 2012-07-27. Retrieved 2009-11-02.

- ^ Hughes, Jay (20 November 1998). "Woman's arm bitten off in zoo attack". Associated Press.

- ^ "Interview with Carlos Manuel Rodriguez Echandi", IUCN Tapir Specialist Group 2006

- ^ Tuite, Tom (14 October 2014) "Dublin Zoo pleads guilty to safety breach in tapir attack on child", The Irish Times

- ^ Goudot, Justin (1843). "Nouvelles observations sur le Tapir Pinchaque" [Recent Observations on the Tapir Pinchaque]. Comptes Rendus. 16: 331–334. Report contains accounts of wild mountain tapirs shying away from human contact at salt deposits after being hunted, and hiding.

- ^ Buck, Frank (2006). Bring 'em Back Alive: The Best of Frank Buck. Texas Tech University Press. pp. 3–. ISBN 978-0-89672-582-9.

- ^ "Native American Indian Tapir Legends, Meaning and Symbolism from the Myths of Many Tribes". www.native-languages.org. Retrieved 2022-06-19.