Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Classical order

View on Wikipedia

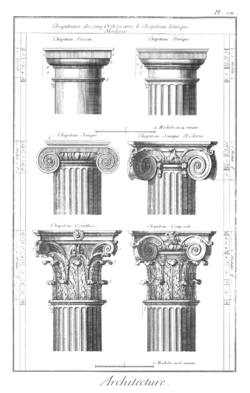

An order in architecture is a certain assemblage of parts subject to uniform established proportions, regulated by the office that each part has to perform.[1] Coming down to the present from Ancient Greek and Ancient Roman civilization, the architectural orders are the styles of classical architecture, each distinguished by its proportions and characteristic profiles and details, and most readily recognizable by the type of column employed. The three orders of architecture—the Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian—originated in Greece. To these the Romans added, in practice if not in name, the Tuscan, which they made simpler than Doric, and the Composite, which was more ornamental than the Corinthian. The architectural order of a classical building is akin to the mode or key of classical music; the grammar or rhetoric of a written composition. It is established by certain modules like the intervals of music, and it raises certain expectations in an audience attuned to its language.[2]

Whereas the orders were essentially structural in Ancient Greek architecture, which made little use of the arch until its late period, in Roman architecture where the arch was often dominant, the orders became increasingly decorative elements except in porticos and similar uses. Columns shrank into half-columns emerging from walls or turned into pilasters. This treatment continued after the conscious and "correct" use of the orders, initially following exclusively Roman models, returned in the Italian Renaissance.[3] Greek Revival architecture, inspired by increasing knowledge of Greek originals, returned to more authentic models, including ones from relatively early periods.

Elements

[edit]Each style has distinctive capitals at the top of columns and horizontal entablatures which it supports, while the rest of the building does not in itself vary between the orders. The column shaft and base also varies with the order, and is sometimes articulated with vertical concave grooves known as fluting. The shaft is wider at the bottom than at the top, because its entasis, beginning a third of the way up, imperceptibly makes the column slightly more slender at the top, although some Doric columns, especially early Greek ones, are visibly "flared", with straight profiles that narrow going up the shaft.

The capital rests on the shaft. It has a load-bearing function, which concentrates the weight of the entablature on the supportive column, but it primarily serves an aesthetic purpose. The necking is the continuation of the shaft, but is visually separated by one or many grooves. The echinus lies atop the necking. It is a circular block that bulges outwards towards the top to support the abacus, which is a square or shaped block that in turn supports the entablature. The entablature consists of three horizontal layers, all of which are visually separated from each other using moldings or bands. In Roman and post-Renaissance work, the entablature may be carried from column to column in the form of an arch that springs from the column that bears its weight, retaining its divisions and sculptural enrichment, if any. There are names for all the many parts of the orders.

Measurement

[edit]

The heights of columns are calculated in terms of a ratio between the diameter of the shaft at its base and the height of the column. A Doric column can be described as seven diameters high, an Ionic column as eight diameters high, and a Corinthian column nine diameters high, although the actual ratios used vary considerably in both ancient and revived examples, but still keeping to the trend of increasing slimness between the orders. Sometimes this is phrased as "lower diameters high", to establish which part of the shaft has been measured.

Greek orders

[edit]There are three distinct orders in Ancient Greek architecture: Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian. These three were adopted by the Romans, who modified their capitals. The Roman adoption of the Greek orders took place in the 1st century BC. The three ancient Greek orders have since been consistently used in European Neoclassical architecture.

Sometimes the Doric order is considered the earliest order, but there is no evidence to support this. Rather, the Doric and Ionic orders seem to have appeared at around the same time, the Ionic in eastern Greece and the Doric in the west and mainland.

Both the Doric and the Ionic order appear to have originated in wood. The Temple of Hera in Olympia is the oldest well-preserved temple of Doric architecture. It was built just after 600 BC. The Doric order later spread across Greece and into Sicily, where it was the chief order for monumental architecture for 800 years. Early Greeks were no doubt aware of the use of stone columns with bases and capitals in ancient Egyptian architecture, and that of other Near Eastern cultures, although there they were mostly used in interiors, rather than as a dominant feature of all or part of exteriors, in the Greek style.

Doric order

[edit]The Doric order originated on the mainland and western Greece. It is the simplest of the orders, characterized by short, organized, heavy columns with plain, round capitals (tops) and no base. With a height that is only four to eight times its diameter, the columns are the most squat of all orders. The shaft of the Doric order is channeled with 20 flutes. The capital consists of a necking or annulet, which is a simple ring. The echinus is convex, or circular cushion like stone, and the abacus is a square slab of stone.

Above the capital is a square abacus connecting the capital to the entablature. The entablature is divided into three horizontal registers, the lower part of which is either smooth or divided by horizontal lines. The upper half is distinctive for the Doric order. The frieze of the Doric entablature is divided into triglyphs and metopes. A triglyph is a unit consisting of three vertical bands which are separated by grooves. Metopes are the plain or carved reliefs between two triglyphs.

The Greek forms of the Doric order come without an individual base. They instead are placed directly on the stylobate. Later forms, however, came with the conventional base consisting of a plinth and a torus. The Roman versions of the Doric order have smaller proportions. As a result, they appear lighter than the Greek orders.

Ionic order

[edit]The Ionic order came from eastern Greece, where its origins are entwined with the similar but little known Aeolic order. It is distinguished by slender, fluted pillars with a large base and two opposed volutes (also called "scrolls") in the echinus of the capital. The echinus itself is decorated with an egg-and-dart motif. The Ionic shaft comes with four more flutes than the Doric counterpart (totalling 24). The Ionic base has two convex moldings called tori, which are separated by a scotia.

The Ionic order is also marked by an entasis, a curved tapering in the column shaft. A column of the Ionic order is nine times more tall than its lower diameter. The shaft itself is eight diameters high. The architrave of the entablature commonly consists of three stepped bands (fasciae). The frieze comes without the Doric triglyph and metope. The frieze sometimes comes with a continuous ornament such as carved figures instead.

Corinthian order

[edit]The Corinthian order is the most elaborated of the Greek orders, characterized by a slender fluted column having an ornate capital decorated with two rows of acanthus leaves and four scrolls. The shaft of the Corinthian order has 24 flutes. The column is commonly ten diameters high.

The Roman writer Vitruvius credited the invention of the Corinthian order to Callimachus, a Greek sculptor of the 5th century BC. The oldest known building built according to this order is the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates in Athens, constructed from 335 to 334 BC. The Corinthian order was raised to rank by the writings of Vitruvius in the 1st century BC.

Roman orders

[edit]

The Romans adapted all the Greek orders and also developed two orders of their own, basically modifications of Greek orders. However, it was not until the Renaissance that these were named and formalized as the Tuscan and Composite, respectively the plainest and most ornate of the orders. The Romans also invented the Superposed order. A superposed order is when successive stories of a building have different orders. The heaviest orders were at the bottom, whilst the lightest came at the top. This means that the Doric order was the order of the ground floor, the Ionic order was used for the middle story, while the Corinthian or the Composite order was used for the top story.

The Giant order was invented by architects in the Renaissance. The Giant order is characterized by columns that extend the height of two or more stories.

Tuscan order

[edit]

The Tuscan order has a very plain design, with a plain shaft, and a simple capital, base, and frieze. It is a simplified adaptation of the Greeks' Doric order. The Tuscan order is characterized by an unfluted shaft and a capital that consists of only an echinus and an abacus. In proportions it is similar to the Doric order, but overall it is significantly plainer. The column is normally seven diameters high. Compared to the other orders, the Tuscan order looks the most solid.

Composite order

[edit]The Composite order is a mixed order, combining the volutes of the Ionic with the leaves of the Corinthian order. Until the Renaissance it was not ranked as a separate order. Instead it was considered as a late Roman form of the Corinthian order. The column of the Composite order is typically ten diameters high.

Historical development

[edit]The Renaissance period saw renewed interest in the literary sources of the ancient cultures of Greece and Rome, and the fertile development of a new architecture based on classical principles. The treatise De architectura by Roman theoretician, architect and engineer Vitruvius, is the only architectural writing that survived from Antiquity. Effectively rediscovered in the 15th century, Vitruvius came to be regarded as the ultimate authority on architecture. However, in his text the word order is not to be found. To describe the four species of columns (he only mentions: Tuscan, Doric, Ionic and Corinthian) he uses, in fact, various words such as: genus (gender), mos (habit, fashion, manner), opera (work).

The term order, as well as the idea of redefining the canon started circulating in Rome, at the beginning of the 16th century, probably during the studies of Vitruvius' text conducted and shared by Peruzzi, Raphael, and Sangallo.[4] Ever since, the definition of the canon has been a collective endeavor that involved several generations of European architects, from Renaissance and Baroque periods, basing their theories both on the study of Vitruvius' writings and the observation of Roman ruins (the Greek ruins became available only after Greek Independence, 1821–1823). What was added were rules for the use of the Architectural Orders, and the exact proportions of them in minute detail. Commentary on the appropriateness of the orders for temples devoted to particular deities (Vitruvius I.2.5) were elaborated by Renaissance theorists, with Doric characterized as bold and manly, Ionic as matronly, and Corinthian as maidenly.[5]

Vignola defining the concept of "order"

[edit]

Following the examples of Vitruvius and the five books of the Regole generali di architettura sopra le cinque maniere de gli edifici by Sebastiano Serlio published from 1537 onwards, Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola produced an architecture rule book that was not only more practical than the previous two treatises, but also was systematically and consistently adopting, for the first time, the term 'order' to define each of the five different species of columns inherited from antiquity. A first publication of the various plates, as separate sheets, appeared in Rome in 1562, with the title: Regola delli cinque ordini d'architettura ("Canon of the Five Orders of Architecture").[6] As David Watkin has pointed out, Vignola's book "was to have an astonishing publishing history of over 500 editions in 400 years in ten languages, Italian, Dutch, English, Flemish, French, German, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish, Swedish, during which it became perhaps the most influential book of all times".[7]

The book consisted simply of an introduction followed by 32 annotated plates, highlighting the proportional system with all the minute details of the Five Architectural Orders. According to Christof Thoenes, the main expert of Renaissance architectural treatises, "in accordance with Vitruvius's example, Vignola chose a "module" equal to a half-diameter which is the base of the system. All the other measurements are expressed in fractions or in multiples of this module. The result is an arithmetical model, and with its help each order, harmoniously proportioned, can easily be adapted to any given height, of a façade or an interior. From this point of view, Vignola's Regola is a remarkable intellectual achievement".[8]

In America, The American Builder's Companion,[9] written in the early 19th century by the architect Asher Benjamin, influenced many builders in the eastern states, particularly those who developed what became known as the Federal style. The last American re-interpretation of Vignola's Regola, was edited in 1904 by William Robert Ware.[10]

The break from the classical mode came first with the Gothic Revival architecture, then the development of modernism during the 19th century. The Bauhaus promoted pure functionalism, stripped of ornament considered superfluous, and that has become one of the defining characteristics of modern architecture. There are some exceptions. Postmodernism introduced an ironic use of the orders as a cultural reference, divorced from the strict rules of composition. On the other hand, a number of practitioners such as Quinlan Terry in England, and Michael Dwyer, Richard Sammons, and Duncan Stroik in the United States, continue the classical tradition, and use the classical orders in their work.

Nonce orders

[edit]Several orders, usually based upon the composite order and only varying in the design of the capitals, have been invented under the inspiration of specific occasions, but have not been used again. They are termed "nonce orders" by analogy to nonce words; several examples follow below.

These nonce orders all express the "speaking architecture" (architecture parlante) that was taught in the Paris courses, most explicitly by Étienne-Louis Boullée, in which sculptural details of classical architecture could be enlisted to speak symbolically, the better to express the purpose of the structure and enrich its visual meaning with specific appropriateness. This idea was taken up strongly in the training of Beaux-Arts architecture, c. 1875–1915.[citation needed]

French order

[edit]The Hall of Mirrors in the Palace of Versailles contains pilasters with bronze capitals in the "French order". Designed by Charles Le Brun, the capitals display the national emblems of the Kingdom of France: the royal sun between two Gallic roosters above a fleur-de-lis.[11]

British orders

[edit]Robert Adam's brother James was in Rome in 1762, drawing antiquities under the direction of Clérisseau; he invented a "British order" and published an engraving of it. Its capital the heraldic lion and unicorn take the place of the Composite's volutes, a Byzantine or Romanesque conception, but expressed in terms of neoclassical realism. Adam's ink-and-wash rendering with red highlighting is at the Avery Library, Columbia University.

In 1789 George Dance invented an Ammonite order, a variant of Ionic, substituting volutes in the form of fossil ammonites for John Boydell's Shakespeare Gallery in Pall Mall, London.[12]

An adaptation of the Corinthian order by William Donthorne that used turnip leaves and mangelwurzel is termed the Agricultural order.[13][14]

Sir Edwin Lutyens, who from 1912 laid out New Delhi as the new seat of government for the British Empire in India,[15] designed a Delhi order having a capital displaying a band of vertical ridges, and with bells hanging at each corner as a replacement for volutes.[16] His design for the new city's central palace, Viceroy's House, now the Presidential residence Rashtrapati Bhavan, was a thorough integration of elements of Indian architecture into a building of classical forms and proportions,[17] and made use of the order throughout.[16] The Delhi Order reappears in some later Lutyens buildings including Campion Hall, Oxford.[18]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

American orders

[edit]

In the United States Benjamin Latrobe, the architect of the Capitol building in Washington, DC, designed a series of botanical American orders. Most famous is the Corinthian order substituting ears of corn and their husks for the acanthus leaves, which was executed by Giuseppe Franzoni and used in the small domed vestibule of the Senate. Only this vestibule survived the Burning of Washington in 1814, nearly intact.[19]

With peace restored, Latrobe designed an American order that substituted tobacco leaves for the acanthus, of which he sent a sketch to Thomas Jefferson in a letter, 5 November 1816. He was encouraged to send a model of it, which remains at Monticello. In the 1830s Alexander Jackson Davis admired it enough to make a drawing of it. In 1809 Latrobe invented a second American order, employing magnolia flowers constrained within the profile of classical mouldings, as his drawing demonstrates. It was intended for "the Upper Columns in the Gallery of the Entrance of the Chamber of the Senate".[20]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Gwilt, Joseph (1842). An Encyclopædia of Architecture: Historical, Theoretical, and Practical. London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans. pp. 680.

An order in architecture is a certain assemblage of parts subject to uniform established proportions, regulated by the office that each part has to perform.

- ^ Summerson, pp. 7–15

- ^ Summerson, pp. 19–21

- ^ H. Burns and H. Gunthers, 24éme Colloque International d'Etude Humanistes, Tours 1981

- ^ Small, Julian. "Classical Orders". sites.scran.ac.uk. Retrieved 2023-08-12.

- ^ The most recent English translation is the one, with an introduction and commentary by Branko Mitrovic, New York. 1999

- ^ David Watkin, Introduction to the Canon of the Five Orders of Architecture, translated by John Leeke, reprint of the 1699 edition, New York, 2011

- ^ "Architectura – Les livres d'Architecture".

- ^ Benjamin, Asher (1827). The American Builder's Companion: Or, a System of Architecture Particularly Adapted to the Present Style of Building. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-22236-3.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Ware, William R. (1994). The American Vignola: a guide to the making of classical architecture. Courier Dover Publications. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-486-28310-4.

- ^ Fouin, Christophe, et al. (2016). Le Château de Versailles. Vu par ses photographes. Paris: Albin Michel. p. 83. ISBN 9782226321428.

- ^ Curl, James Stevens; Wilson, Susan (2016). Oxford Dictionary of Architecture. Oxford University Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-19-967499-2.

- ^ Curl, p. 238

- ^ Curl, p. 11

- ^ Gradidge, Roderick (1981). Edwin Lutyens: Architect Laureate. London, UK: George Allen and Unwin. p. 69. ISBN 0-04-720023-5.

- ^ a b Gradidge, Roderick (1981). Edwin Lutyens: Architect Laureate. London: George Allen and Unwin. p. 151. ISBN 0-04-720023-5.

- ^ Wilhide, Elizabeth (2012). Sir Edwin Lutyens: Designing in the English tradition. London: National Trust Books. pp. 41–42. ISBN 9781907892271.

- ^ Gradidge, Roderick (1981). Edwin Lutyens: Architect Laureate. London: George Allen and Unwin. p. 161. ISBN 0-04-720023-5.

- ^ "The 1814 burning of Washington, D.C." www.cbsnews.com. 31 August 2014. Retrieved 2022-12-21.

- ^ "United States Capitol exhibit". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 2017-07-15. Retrieved 2017-12-29.

References

[edit]- Summerson, John, The Classical Language of Architecture, 1980 edition, Thames and Hudson World of Art series, ISBN 0500201773

- Frédérique Lemerle et Yves Pauwels (dir.), Histoires d’ordres: le langage européen de l’architecture, Turhout, Brepols, 2021

Further reading

[edit]- Barletta, Barbara A., The Origins of the Greek Architectural Orders (Cambridge University Press) 2001

- Barozzi da Vignola, Giacomo, Canon of the Five Orders, Translated into English, with an introduction and commentary by Branko Mitrovic, Acanthus Press, New York, 1999

- Barozzi da Vignola, Giacomo, Canon of the Five Orders, Translated by John Leeke (1669), with an introduction by David Watkin, Dover Publications, New York, 2011

- Chitham, Robert (2004). The Classical Orders of Architecture (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 9780080470573.

- James Stevens Curl (2003). Classical Architecture: An Introduction to Its Vocabulary and Essentials, With a Select Glossary of Terms. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-73119-4.

- John Newenham Summerson (1963). The Classical Language of Architecture. The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-69012-6.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Tzonis, Alexander; Lefaivre, Liane (1986). Classical architecture: the poetics of order. The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-70031-3.

- Gromort, Georges (2001). The Elements of Classical Architecture. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-73051-7.

- Classical orders and elements

- Spiers, Richard Phené (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). pp. 176–183.

_by_Paolo_Villa_ENG_edition.pdf/page1-232px-ARCHITECTURE_ORDERS_Greeks_Etruscan_Roman_(Doric_Ionic_Corinthian_Tuscan_Composite)_by_Paolo_Villa_ENG_edition.pdf.jpg)

_by_Paolo_Villa_ENG_edition.pdf/page1-2000px-ARCHITECTURE_ORDERS_Greeks_Etruscan_Roman_(Doric_Ionic_Corinthian_Tuscan_Composite)_by_Paolo_Villa_ENG_edition.pdf.jpg)