Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Common box turtle

View on Wikipedia

| Common box turtle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Cryptodira |

| Family: | Emydidae |

| Genus: | Terrapene |

| Species: | T. carolina

|

| Binomial name | |

| Terrapene carolina | |

| Subspecies | |

|

See text | |

| Synonyms[3] | |

The common box turtle (Terrapene carolina) is a species of box turtle with five existing subspecies. It is found throughout the Eastern United States and Mexico. The box turtle has a distinctive hinged lower shell that allows it to completely enclose itself, like a box. Its upper jaw is hooked. The turtle is primarily terrestrial and eats a wide variety of plants and animals. The females lay their eggs in the summer. Turtles in the northern part of their range hibernate over the winter.

Common box turtle numbers are declining because of habitat loss, roadkill, and capture for the pet trade. The species is classified as vulnerable to threats to its survival by the IUCN Red List. Two states have chosen subspecies of the common box turtle as their official state reptile: T. c. carolina in North Carolina and Tennessee.

Classification

[edit]Terrapene carolina was first described by Carl Linnaeus in his landmark 1758 10th edition of Systema Naturae. It is the type species for the genus Terrapene and has more subspecies than the other three species within that genus. The eastern box turtle subspecies was the one recognized by Linnaeus. The other four subspecies were first classified during the 19th century.[4] In addition, one extinct subspecies, T. c. putnami, is distinguished.[5]

- Subspecies

| Image | Common name | Subspecies |

|---|---|---|

|

Eastern box turtle | Terrapene carolina carolina

(Linnaeus, 1758) |

|

Florida box turtle | Terrapene carolina bauri

Taylor, 1895 |

|

Gulf Coast box turtle | Terrapene carolina major

(Agassiz, 1857) |

|

Mexican box turtle | Terrapene carolina mexicana

(Gray, 1849) |

|

Yucatán box turtle | Terrapene carolina yucatana

(Boulenger, 1895) |

| Giant box turtle | †Terrapene carolina putnami

O.P. Hay, 1906 |

Nota bene: Parentheses around the name of an authority indicate the subspecies was originally described in a genus other than Terrapene.

Description

[edit]

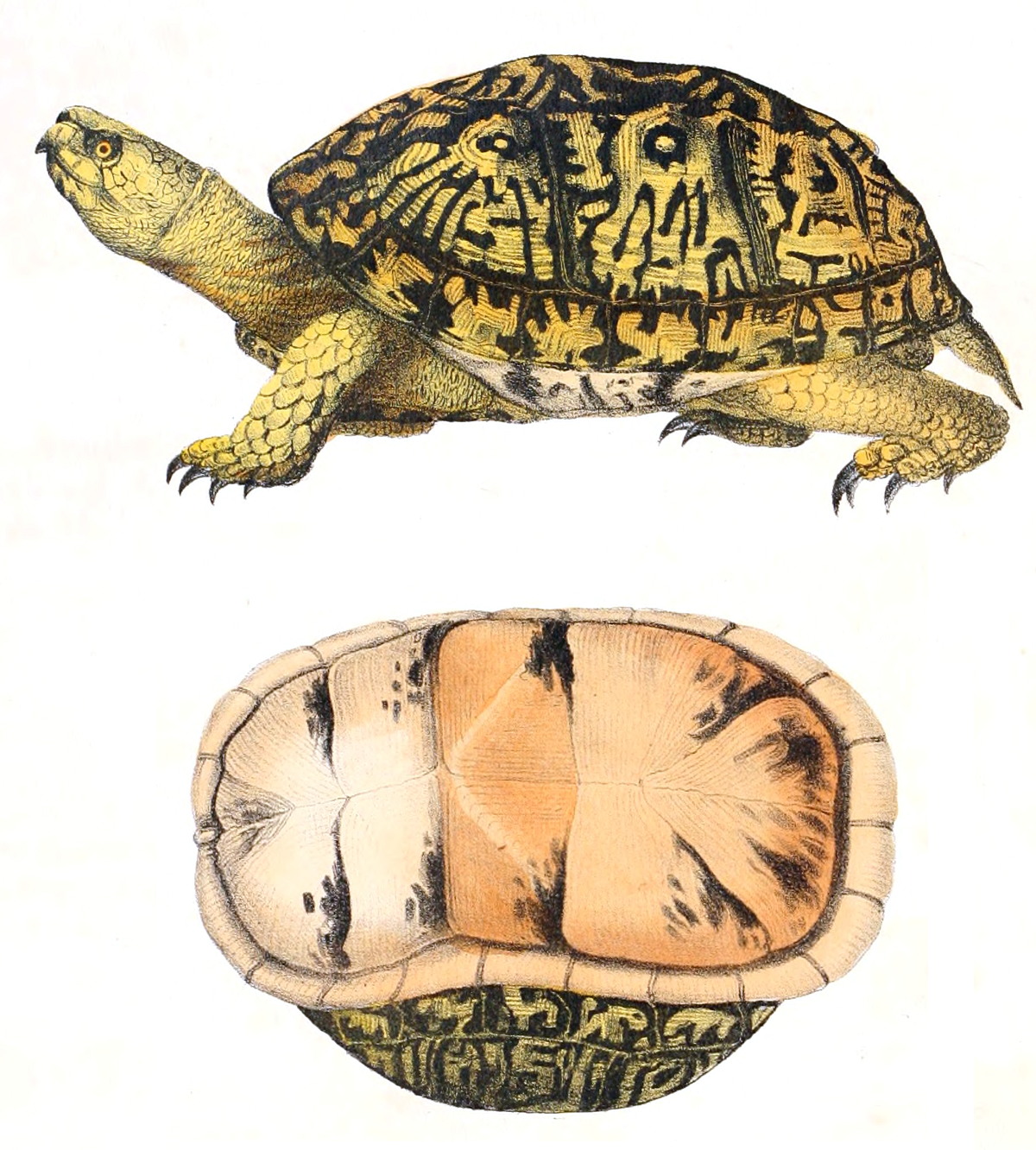

The common box turtle (Terrapene carolina) gets its common name from the structure of its shell which consists of a high domed carapace (upper shell), and large, hinged plastron (lower shell) which allows the turtle to close the shell, sealing its vulnerable head and limbs safely within an impregnable box.[6] The carapace is brown, often adorned with a variable pattern of orange or yellow lines, spots, bars or blotches. The plastron is dark brown and may be uniformly coloured, or show darker blotches or smudges.[7]

The common box turtle has a small to moderately sized head and a distinctive hooked upper jaw.[7] The majority of adult male common box turtles have red irises, while those of the female are yellowish-brown. Males also differ from females by possessing shorter, stockier and more curved claws on their hind feet, and longer and thicker tails.[7]

There are five living subspecies of the common box turtle, each differing slightly in appearance, namely in the colour and patterning of the carapace, and the possession of either three or four toes on each hind foot.

Distribution

[edit]The common box turtle inhabits open woodlands, marshy meadows, floodplains, scrub forests and brushy grasslands[6][7] in much of the eastern United States, from Maine and Michigan to eastern Texas and south Florida. It was once found in Canada in southern Ontario and is still found in Mexico along the Gulf Coast and in the Yucatán Peninsula.[1][7] The species range is not continuous as the two Mexican subspecies, T. c. mexicana (Mexican box turtle) and T. c. yucatana (Yucatán box turtle), are separated from the US subspecies by a gap in western Texas. Three of the US subspecies; T. c. carolina (eastern box turtle), T. c. major (Gulf Coast box turtle) and T. c. bauri (Florida box turtle); occur roughly in the areas indicated by their names. The species has become extirpated from Ontario and Canada.[8]

Behavior

[edit]

Common box turtles are predominantly terrestrial reptiles that are often seen early in the day, or after rain, when they emerge from the shelter of rotting leaves, logs, or a mammal burrow to forage. These turtles have an incredibly varied diet of animal and plant matter, including earthworms, snails, slugs, insects, wild berries, roots, flowers, fungi, fish, frogs, salamanders, snakes, birds, eggs, and sometimes even animal carrion (in the form of dead ducks, amphibians, assorted small mammals, and even a dead cow).[6][7][9]

In the warmer summer months, common box turtles are more likely to be seen near the edges of swamps or marshlands,[6] possibly in an effort to stay cool. If common box turtles do become too hot, (when their body temperature rises to around 32 °C), they smear saliva over their legs and head; as the saliva evaporates it leaves them comfortably cooler. Similarly, the turtle may urinate on its hind limbs to cool the body parts it is unable to cover with saliva.[10]

Courtship in the common box turtle, which usually takes place in spring, begins with a "circling, biting and shoving" phase. These acts are carried out by the male on the female.[7] Following some pushing and shell-biting, the male grips the back of the female's shell with his hind feet to enable him to lean back, slightly beyond the vertical, and mate with the female.[11] Remarkably, female common box turtles can store sperm for up to four years after mating,[7] and thus do not need to mate each year.[11]

In May, June or July, females normally lay a clutch of 1 to 11 eggs into a flask-shaped nest excavated in a patch of sandy or loamy soil. After 70 to 80 days of incubation, the eggs hatch, and the small hatchlings emerge from the nest in late summer. In the northern parts of its range, the common box turtle may enter hibernation in October or November. They burrow into loose soil, sand, vegetable matter, or mud at the bottom of streams and pools, or they may use a mammal burrow, and will remain in their chosen shelter until the cold winter has passed.[7] The common box turtle has been known to attain the greatest lifespan of any vertebrate outside of the tortoises. One specimen lived to be at least 138 years of age.[12]

Human interaction

[edit]Conservation

[edit]Although the common box turtle has a wide range and was once considered common, many populations are in decline as a result of a number of diverse threats. Agricultural and urban development is destroying habitat, while human fire management is degrading it.[1] Development brings with it an additional threat in the form of increased infrastructure, as common box turtles are frequently killed on roads and highways. Collection for the international pet trade may also impact populations in some areas.[7][8] The life history characteristics of the common box turtle (long lifespan and slow reproductive rate)[7] make it particularly vulnerable to such threats. The common box turtle is therefore classified as a vulnerable species on the IUCN Red List.[1] The common box turtle is also listed on Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), meaning that international trade in this species should be carefully monitored to ensure it is compatible with the species' survival.[2] In addition, many U.S. states regulate or prohibit the taking of this species.[7] NatureServe considers it Secure.[8]

This species also occurs in a number of protected areas, some of which are large enough to protect populations from the threat of development, while it may also occur in the Sierra del Abra Tanchipa Biosphere Reserve, Mexico. Conservation recommendations for the common box turtle include establishing management practices during urban developments that are sympathetic to this species, as well as further research into its life history and the monitoring of populations.[1]

State reptiles

[edit]"The turtle watches undisturbed as countless generations of faster 'hares' run by to quick oblivion, and is thus a model of patience for mankind, and a symbol of our State's unrelenting pursuit of great and lofty goals."

Common box turtles are official state reptiles of three U.S. states. North Carolina and Tennessee honor the eastern box turtle,[14][15][16] Kansas adopted the ornate box turtle in 1986.[17][18]

In Pennsylvania, the eastern box turtle made it through one house of the legislature, but failed to win final naming in 2009.[19] In Virginia, bills to honor the eastern box turtle failed in 1999 and then in 2009. Although a sponsor of the original failed 1998 bill,[20] in 2009, Delegate Frank Hargrove, of Hanover, asked why Virginia would make an official emblem of an animal that retreats into its shell when frightened and dies by the thousands crawling across roads. However, the main problem in Virginia was that the creature was too closely linked to neighbor state North Carolina.[21][22]

References

[edit]This article incorporates text from the ARKive fact-file "Common box turtle" under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License and the GFDL.

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e van Dijk, P.P. (2016) [errata version of 2011 assessment]. "Terrapene carolina". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011 e.T21641A97428179. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-1.RLTS.T21641A9303747.en. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ a b "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ^ Fritz Uwe; Peter Havaš (2007). "Checklist of Chelonians of the World". Vertebrate Zoology. 57 (2): 198. doi:10.3897/vz.57.e30895. S2CID 87809001.

- ^ Fritz 2007, p. 196

- ^ Dodd, pp. 24–30

- ^ a b c d Capula, M. (1990). The Macdonald Encyclopedia of Amphibians and Reptiles. London: Macdonald and Co Ltd.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Ernst, C. H.; Altenbourgh, R. G. M.; Barbour, R. W. (1997). Turtles of the World. Netherlands: ETI Information Systems Ltd. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ a b c "Terrapene carolina. NatureServe Explorer 2.0". explorer.natureserve.org. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- ^ Niedzielski, Steven (2002). Wund, Matthew (ed.). "Terrapene carolina (Florida Box Turtle)". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ Alderton, D. (1988). Turtles and Tortoises of the World. London: Blandford Press.

- ^ a b Halliday, T.; Adler, K. (2002). The New Encyclopedia of Reptiles and Amphibians. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Wood, Gerald (1983). The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. Guinness Superlatives. ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9.

- ^ "Eastern Box Turtle – North Carolina State Reptiles". North Carolina Department of the Secretary of State. Archived from the original on 25 January 2011. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- ^ Shearer 1994, p. 321

- ^ "Official State Symbols of North Carolina". North Carolina State Library. State of North Carolina. Retrieved 26 January 2008.

- ^ "Tennessee Symbols And Honor" (PDF). Tennessee Blue Book: 526. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- ^ "Kansas Quick Facts". Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- ^ "Ornate Box Turtle State Symbols USA". statesymbolsusa.org. 23 May 2014. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ^ "Regular Session 2009–2010: House Bill 621". Pennsylvania State Legislature. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

- ^ "980757252 - House Bill No. 1109". 26 January 1998. Archived from the original on 30 March 2025.

- ^ "SB 1504 Eastern Box Turtle; designating as official state reptile". Virginia State Legislature. Archived from the original on 16 January 2010. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

- ^ "Virginia House crushes box turtle's bid to be state reptile". NBC Washington. Associated Press. 20 February 2009. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

Bibliography

[edit]- Dodd Jr., C. Kenneth (2002). North American Box Turtles: A Natural History. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3501-4.

- Fritz, Uwe; Havaš, Peter (2007). "Checklist of Chelonians of the World". Vertebrate Zoology. 57 (2): 149–368. doi:10.3897/vz.57.e30895. S2CID 87809001.

- Shearer, Benjamin F.; Shearer, Barbara S. (1994). State names, seals, flags, and symbols (2nd ed.). Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-28862-3.

External links

[edit]Common box turtle

View on GrokipediaTaxonomy

Classification and phylogeny

The common box turtle (Terrapene carolina) is classified in the domain Eukarya, kingdom Animalia, phylum Chordata, class Reptilia, order Testudines, suborder Cryptodira, superfamily Testudinoidea, family Emydidae, subfamily Emydinae, genus Terrapene, and species T. carolina.[8][9] This placement reflects its membership in the diverse Emydidae family, which encompasses approximately 50–60 extant species of primarily aquatic or semi-aquatic turtles, though Terrapene species are notably terrestrial.[10] Phylogenetic analyses, incorporating both morphological and molecular data, position the genus Terrapene as monophyletic within Emydidae, diverging from other lineages during the Miocene epoch around 20–15 million years ago based on multigene time-calibrated trees.[11] Within Terrapene, T. carolina forms a clade distinct from congeners such as T. ornata (ornate box turtle) and T. mexicana (Mexican box turtles), with sequence-based phylogenies resolving T. carolina as basal to a group including T. coahuila (Coahuilan box turtle).[12] However, intraspecific relationships within T. carolina exhibit complexity, with morphological variation challenging subspecies boundaries; for instance, molecular evidence indicates that the Gulf Coast box turtle (T. c. major) lacks a distinct evolutionary lineage in the Florida Panhandle, suggesting gene flow or recent divergence rather than deep splits.[13][14][15] Fossil records support the antiquity of Terrapene-like forms, with Pleistocene fossils blurring lines between extant T. carolina subspecies and extinct taxa, implying that modern variation may partly stem from historical range contractions rather than isolated adaptive radiations.[16] Comprehensive Emydidae phylogenies underscore Terrapene's sister-group relationship to pond turtle clades like Emys and Trachemys, highlighting a shared ancestry adapted to North American temperate environments before terrestrial specialization in box turtles.[11][10]Subspecies

The common box turtle (Terrapene carolina) is traditionally divided into five subspecies, distinguished primarily by geographic distribution, shell patterning, and minor morphological traits such as the number of hind toes.[17] [18] However, taxonomic treatments differ; the Turtle Taxonomy Working Group (2021) recognizes only three subspecies under T. carolina (T. c. carolina, T. c. bauri, and T. c. major), with others elevated to species level based on genetic divergence and phylogeographic evidence.[19] [20] These variations stem from phylogenetic studies indicating deep evolutionary splits, though subspecies designations persist in many conservation and field guides due to overlapping traits and hybridization potential.[2]- Eastern box turtle (T. c. carolina): The nominotypical subspecies, ranging from southern Maine and New York southward to Florida and westward to Michigan, Illinois, Kansas, and eastern Texas.[17] It typically exhibits a dark brown to black carapace with yellow, orange, or red radiating lines or spots on each scute, and four hind toes.[2] This form is the most widespread and commonly encountered in deciduous forests and woodlands.

- Three-toed box turtle (T. c. triunguis): Distributed in the central United States, from southern Indiana and Illinois through Oklahoma and Texas to Louisiana.[17] Characterized by three hind toes (versus four in other subspecies) and a carapace with fewer, more subdued yellow lines or spots, often appearing plain or with concentric markings.[18] Genetic analyses suggest it may warrant species status (Terrapene triunguis), but it remains classified as a subspecies in some frameworks.[20]

- Gulf Coast box turtle (T. c. bauri): Confined to coastal regions from extreme southeastern Georgia through the Florida Panhandle to Mississippi.[2] It features a highly domed, keeled carapace with bold yellow stripes or spots and a yellowish plastron.[17] Recent revisions often treat it as a distinct species (Terrapene bauri) due to pronounced genetic isolation.[19]

- Florida box turtle (T. c. major): Endemic to peninsular Florida, south of the Suwannee River.[2] The largest subspecies, with adults reaching up to 210 mm carapace length, it has a strongly keeled shell with dark background and prominent yellow markings.[17] Like T. c. bauri, it is sometimes elevated to full species (Terrapene major) in modern taxonomy.[19]

- Yucatán box turtle (T. c. yucatana): Restricted to the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico, including Quintana Roo and Yucatán states.[18] It displays a carapace with intricate yellow networks or vermiculations on a dark base, adapted to tropical habitats.[6] This peripheral population shows genetic distinctiveness but is retained as a subspecies pending further study.[20]

Physical description

Morphology and coloration

The common box turtle exhibits a robust, terrestrial morphology characterized by a high-domed carapace formed by fused bony plates covered in keratinous scutes, typically featuring a low central keel along the vertebral scutes. The carapace consists of 54 scutes in total, including one nuchal, four vertebrals, eight costals, 24 marginals, and a supracaudal, with patterns often displaying concentric growth rings indicative of age.[21] The plastron comprises 13 scutes and includes a distinctive single transverse hinge located between the pectoral and abdominal scutes, enabling complete enclosure of the head, limbs, and tail for defense.[3] [1] Carapace coloration is highly variable among individuals, generally dark brown to black with radiating yellow, orange, or red lines, streaks, spots, or mottling emanating from the center of each scute, though patterns may fade to a more uniform tan in older specimens.[22] [23] The plastron is typically yellowish to dark brown, sometimes with lighter markings near the hinge.[3] Skin on the head, neck, and limbs is dark brown or black, accented by yellow or orange spots, stripes, or suffusions, with males displaying brighter hues.[22] [3] Sexual dimorphism is evident in shell shape, with males possessing a concave plastron and slightly lower-domed carapace, while females have a flat plastron and more pronounced dome.[24] [7] Males also exhibit red eyes, larger heads, thicker tails, and often more vivid coloration on the head and forelimbs compared to females' brown eyes and duller tones.[22] [24] The head is broad with a slightly hooked beak, and limbs are short and stout, with forelimbs bearing large, overlapping scales and hind limbs varying in toe count by subspecies (e.g., two to four toes).[23] [3]Size, growth, and longevity

Adult Terrapene carolina specimens typically reach a carapace length of 11 to 20 cm (4.5 to 8 inches), with most adults measuring 12 to 15 cm (5 to 6 inches).[1][25] Weight generally ranges from 300 to 500 g (0.7 to 1.1 lb), though larger individuals may exceed 900 g (2 lb).[26][27] Males tend to be slightly larger than females, with subspecies variation; for example, eastern box turtles (T. c. carolina) average 13.2 cm in carapace length for males.[28] Hatchlings emerge with a carapace length of approximately 3 cm (1.2 inches) and weigh about 8 g (0.03 oz).[29] Growth is indeterminate but slows markedly after sexual maturity, which occurs around 7 to 10 years of age at a carapace length of 10 to 12 cm.[30] Juveniles grow at a rate of roughly 1 to 1.3 cm (0.4 to 0.5 inches) per year in the first 5 years under optimal conditions, influenced by diet, temperature, and habitat quality; wild individuals exhibit slower growth due to resource limitations compared to captives, as evidenced by annual growth rings on scutes.[31][32] Full adult size is approached after 20 years, with minimal increment thereafter.[31] In the wild, T. carolina commonly lives 25 to 50 years, though documented individuals have exceeded 100 years, limited primarily by predation, habitat loss, and disease rather than senescence.[17][33][1] Captive specimens with proper husbandry—encompassing varied diet, UVB exposure, and space—often achieve 40 to 100 years, surpassing wild longevity due to reduced extrinsic mortality.[17][25][34] Age estimation via scute rings is unreliable, as ring formation correlates more with environmental stressors than chronological time.Distribution and habitat

Geographic range

The common box turtle (Terrapene carolina) occupies a broad range across the eastern and central United States, extending from southern Maine and southern Ontario southward to the Gulf Coast, and westward into the Midwest. This distribution spans approximately 26 states, with the northern limits reaching parts of New York, Michigan, and Wisconsin, while the southern boundary includes Florida, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and eastern Texas.[2][35] Range limits vary by subspecies, which influence local distributions within the overall species extent. The eastern subspecies (T. c. carolina) predominates in the northeastern and southeastern portions, from New England to the Carolinas and into southern Florida. The Gulf Coast subspecies (T. c. major) occurs along the coastal plain from eastern Texas to Mississippi, while the three-toed subspecies (T. c. triunguis) inhabits interior regions of the central states, including Missouri, Arkansas, and Louisiana. The Florida subspecies (T. c. bauri) is restricted to peninsular Florida, and T. c. yucatana extends the species' range into northeastern Mexico.[35][2] Historically, the range has contracted in northern and western margins due to habitat loss and climate factors, with extirpations reported in parts of New England and the upper Midwest by the late 20th century, though core populations persist in forested and grassland mosaics of the Southeast and Midwest. Current estimates indicate fragmented distributions in urbanized areas, with continuous occupancy in rural woodlands from southern Pennsylvania to northern Florida.[2]Habitat preferences and microhabitats

The common box turtle (Terrapene carolina) primarily inhabits upland deciduous and mixed forests, woodland edges, open meadows, pastures, and thickets, favoring areas with well-drained loamy, sandy, or gravelly soils that facilitate burrowing and nesting.[36] [37] These habitats often occur in regions with moderate moisture, including proximity to streams, ponds, marshes, or swamps, though the species remains predominantly terrestrial and avoids fully aquatic environments.[36] In the northeastern United States, closed-canopy forests provide summer refuge, while open-canopy uplands support nesting; southern populations may utilize pine-hardwood stands.[37] [38] Microhabitat selection emphasizes thermal and hydric regulation, with turtles preferring sites featuring dense understory cover, leaf litter layers, and woody debris such as fallen logs or brush piles that retain moisture and moderate surface temperatures.[39] [37] Compared to random locations, selected microhabitats exhibit lower surface temperatures, higher relative humidity, and greater understory density, aiding thermoregulation in forested wetlands or uplands.[39] During hot or dry conditions, individuals bury into leaf litter or under rotting logs for shelter; post-rain activity increases as humidity rises.[36] Nesting microhabitats consist of open, unshaded areas with sparse native ground cover (e.g., 5-25% grasses or sedges), southern aspects for solar exposure, and loose soils low in clay (<5%) to enable egg deposition from early June to mid-July.[37] [36] These sites differ from random points in vegetation height, ground and canopy cover percentages, and light intensity, prioritizing predator avoidance through partial concealment while ensuring adequate warmth for incubation.[40] Overall, habitat quality hinges on structural heterogeneity, including retained snags and debris, to support foraging, refuge, and reproduction without excessive disturbance.[37]Behavior and ecology

Daily and seasonal activities

The common box turtle (Terrapene carolina) is primarily diurnal, emerging from nocturnal shelters in moist soil forms or leaf litter to engage in activities such as basking and foraging during daylight hours. Activity peaks in the morning and evening, with individuals often sunning in forest clearings adjacent to cover before moving to feed, though midday heat may prompt retreat to shaded refuges under logs, brush piles, or tangled vines. Rain showers frequently trigger increased surface activity, as precipitation enhances humidity and mobility across leaf litter substrates.[41][2][42] Seasonally, activity commences in April following winter dormancy and persists through October or November in northern ranges, with highest levels in spring and fall under moderate temperatures and frequent rains. Summer imposes constraints via elevated heat, leading to abbreviated morning forays or post-rain excursions, supplemented by aestivation in cool, humid microhabitats like mud burrows or stream edges. In preparation for winter, turtles enter brumation—a dormancy state rather than true hibernation—by late October or November, excavating shallow cavities in soil, leaf debris, or rotten logs at depths averaging 5–6 cm, where they tolerate subfreezing conditions but risk mortality from premature thaws. Emergence occurs in March or April when soil temperatures exceed 7°C (45°F) for at least five consecutive days or ambient air reaches 18°C (65°F), with southern populations often forgoing full brumation and remaining sporadically active during mild winters.[41][2][1]Diet and foraging

The common box turtle (Terrapene carolina) is an opportunistic omnivore whose diet includes a mix of animal and plant matter, varying by seasonal availability, habitat, and individual opportunity. Animal components typically comprise earthworms (annelids), arthropods such as beetles, gastropods (snails and slugs), millipedes, and occasionally small vertebrates like frogs or carrion, while plant matter consists of fruits, berries (e.g., blackberries, strawberries), tender leaves, grasses, seeds, and fungi (including mushrooms). [43] [44] [45] Proportions of these elements are not fixed; empirical analyses of gut contents and fecal samples from wild populations indicate animal matter can constitute 40–60% of the diet in some regions, with insects and earthworms often predominant due to their abundance and nutritional value, though plant material dominates in fruit-rich habitats like pine barrens. [46] [44] Foraging occurs primarily on the forest floor in a deliberate, low-energy manner, with turtles using chemosensory detection via frequent tongue-flicking to locate prey odors over distances of several meters. [47] They actively probe leaf litter, soil, and decaying wood with their snouts, consuming items whole after manipulation with forelimbs or by crushing against the jaw. [45] Activity peaks in June through August, correlating with warmer temperatures (optimal around 25–30°C) and increased prey mobility, though consumption rates decline during droughts or excessive heat when turtles aestivate. [47] As diet generalists, they exhibit flexibility, with fecal pellet analyses from eastern U.S. sites showing incorporation of low-quality but familiar foods like fungi during scarcity, rather than strict selectivity, which supports survival in fragmented habitats. [46] [44] Digestive efficiency varies with food type; for instance, T. carolina processes fruit-based diets (e.g., strawberries, mayapples) more slowly than sympatric species like ornate box turtles, potentially reflecting adaptations to a broader, less specialized gut microbiome. [48] Juveniles prioritize protein-rich animal foods for growth, while adults balance intake for maintenance, with overall foraging influenced by microhabitat features like moist understory cover that enhances prey encounter rates. [43]Reproduction and life cycle

Courtship and mating in the common box turtle (Terrapene carolina) occur primarily from spring through fall, with males pursuing females through visual and tactile displays, including mounting and biting the head or neck.[1] Females can store viable sperm for up to four years, enabling them to produce fertile eggs without annual mating.[7] [30] Nesting typically takes place from May to June, when gravid females excavate shallow nests in sandy or loamy soils exposed to sunlight, depositing clutches of 1 to 7 eggs, with larger females producing bigger clutches averaging 4 to 7 eggs.[49] [50] Eggs are white, elongated, and soft-shelled, measuring about 3 cm in length.[2] Incubation lasts 50 to 103 days, influenced by soil temperature and moisture, with hatching generally occurring in September or October; sex is determined by temperature, cooler conditions favoring males and warmer ones females.[41] [2] Hatchlings emerge fully formed but small, about 3 cm in carapace length, and immediately seek cover, contributing to low observed survival rates as they face high predation.[33] Juveniles grow slowly, gaining approximately 0.5 inches in carapace length annually for the first five years, with growth continuing gradually thereafter.[31] Sexual maturity is reached between 5 and 10 years of age, varying by individual and environmental factors.[1] [33] Adults exhibit low reproductive rates, with females laying at most one clutch per year, underscoring the species' vulnerability due to delayed maturity and infrequent breeding.[2] In the wild, common box turtles live 25 to 30 years on average, though individuals have been documented exceeding 50 years; captive specimens may reach 100 years under optimal conditions.[51] [52] The protracted life cycle, characterized by slow growth, late maturity, and limited fecundity, renders populations sensitive to mortality factors across all stages.[33]Movement patterns and home range

Eastern box turtles (Terrapene carolina) display sedentary behavior with limited dispersal, occupying consistent home ranges year after year and showing high site fidelity rather than migratory patterns.[2] Individuals rarely venture far beyond established areas, with juveniles exhibiting somewhat greater exploratory movements but overall low rates of long-distance dispersal across populations.[53] Home range sizes, estimated primarily via radio telemetry, vary widely due to factors including sex, estimation method (e.g., minimum convex polygon vs. kernel density), local habitat quality, and translocation status, but typically fall between 1 and 28 ha across studies of T. carolina, with a species-wide mean of approximately 7.5 ha.[53] For instance, in a high-resolution VHF radiotracking study in North Carolina (2023), home ranges for T. c. carolina averaged 3.4 ha (range: 1.4–5.9 ha) based on 100% minimum convex polygons from 127–148 locations per individual tracked 5–7 days per week over the active season.[54] Sex-based differences are inconsistent; females in some T. carolina populations maintain ranges 27% larger than males (females: 4.82 ha; males: 3.80 ha), potentially linked to nesting requirements, while other studies report minimal dimorphism.[53] Relocated individuals often expand ranges by up to 50%, suggesting stress-induced behavioral adjustments.[53] Daily movements are modest, averaging 16–28 m (maximum observed: 210 m), reflecting slow terrestrial locomotion and opportunistic foraging within familiar microhabitats.[54] Annual displacements remain confined, with turtles reusing core areas for hibernation, basking, and feeding, though females may temporarily extend ranges for oviposition.[2] Such patterns underscore T. carolina's vulnerability to habitat fragmentation, as barriers exceeding tens of meters can isolate populations.[53]Population dynamics and threats

Population trends and status

The common box turtle (Terrapene carolina) is classified as Vulnerable (VU) on the IUCN Red List, assessed in 2011 under criteria A2bcde+4bcde, reflecting a widespread, persistent, and ongoing gradual population decline over the last 50 years.[6] This decline is estimated to exceed 30% over three generations, driven by multiple factors including habitat loss and fragmentation.[56] Long-term studies, such as one in Maryland spanning from 1945, document consistent reductions in population numbers.[57] A monitored population in Maryland exhibited a 67% decline over 29 years, attributed partly to reduced recruitment rates.[58] Statewide surveys in Indiana reported population densities ranging from 0.2 to 6.0 turtles per hectare, with densities decreasing in areas of higher urbanization.[59] Regional assessments indicate that approximately 51% of habitat in the northeastern United States is impaired, contributing to ongoing population pressures.[60]Natural predators and mortality factors

Adult Terrapene carolina exhibit a hinged plastron enabling full enclosure within their shell, which confers substantial protection against predation for mature individuals.[2] Consequently, few natural predators successfully target adults, though opportunistic mammals such as raccoons (Procyon lotor), striped skunks (Mephitis mephitis), and foxes (Vulpes spp. or Urocyon spp.) may prey upon them during periods of immobility or distraction, such as while feeding or mating.[2][33] Avian predators like great horned owls (Bubo virginianus) and reptilian threats including eastern kingsnakes (Lampropeltis getula) occasionally overcome this defense by persistent attack or exploitation of shell gaps.[27][2] Eggs and juveniles, lacking full shell development, incur far higher predation rates from a broader array of species. Nest predation is perpetrated by ants, crows (Corvus spp.), raccoons, skunks, opossums (Didelphis virginiana), and rodents such as eastern chipmunks (Tamias striatus) and gray squirrels (Sciurus carolinensis), with reported rates reaching 87-100% in unprotected sites across fragmented forests.[33][28][61] Hatchlings and subadults remain vulnerable to these mammals, as well as shrews (Sorex spp.), birds, and snakes, due to incomplete hing ing and smaller size.[41] Beyond predation, infectious diseases represent a significant natural mortality driver. Ranavirus (e.g., frog virus 3, FV3) has triggered episodic die-offs in wild populations, with necropsies confirming systemic infection leading to rapid adult and juvenile mortality.[62][63] Emerging pathogens like Terrapene herpesvirus 1 (TerHV1) and box turtle adenovirus 1 contribute to similar events, often compounded by environmental stressors such as drought or overcrowding in remnant habitats.[62] Parasitic loads, including nematodes and trematodes, can exacerbate vulnerability but rarely act as primary causes.Anthropogenic threats

Habitat loss and fragmentation from urbanization, agriculture, and residential development represent primary anthropogenic threats to Terrapene carolina, reducing available woodland and forest edges essential for the species' survival.[60] These activities fragment habitats, isolating populations and limiting gene flow, with studies indicating that eastern box turtle abundance declines with increasing urban land use.[64] Agricultural practices, including frequent mowing of hay fields, exacerbate this by attracting turtles from adjacent forests to forage, only to expose them to machinery and desiccation risks.[60] Road mortality from vehicle strikes is a significant direct cause of adult mortality, as box turtles' slow terrestrial movement patterns increase encounters with traffic during dispersal or foraging.[65][6] In fragmented landscapes, roads act as barriers, with human-induced mortality from vehicles documented as a key factor in population declines across the species' range.[66] Illegal collection for the pet trade further depletes populations, particularly of adults and juveniles, with removal from wild habitats contributing to observed declines in multiple regions.[65][67] Pesticide use and pollution from agricultural runoff pose additional risks by contaminating food sources and potentially causing sublethal effects or direct poisoning, though quantitative impacts remain understudied.[65] Prescribed burns during the active growing season heighten mortality risks, as surface-active turtles suffer from fire exposure in managed habitats.[68]Conservation and management

Legal protections and status

The common box turtle (Terrapene carolina) is classified as Vulnerable (VU) on the IUCN Red List, based on observed population declines driven by habitat fragmentation, road mortality, and collection for the pet trade, with assessments indicating a reduction exceeding 30% over three generations.[6][56] Internationally, the species is listed under Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), which requires permits for export to ensure trade does not threaten survival, implemented since proposals in the late 1980s and affecting all Terrapene species except the critically endangered T. coahuila.[69][70] In the United States, the common box turtle lacks federal protection under the Endangered Species Act, as it is not listed as endangered or threatened by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, reflecting its relatively secure global status (G5 per NatureServe) despite local declines.[71][19] Protections vary by state within its range; for example, it is designated as threatened in Michigan, species of special concern in Massachusetts and Connecticut, and collection from the wild has been prohibited in Indiana since 2004.[36][3][7][33] In North Carolina, possession, sale, or taking of five or more individuals from the wild is unlawful, classified as commercial activity to curb pet trade impacts.[22] Many states require permits for captive care or rehabilitation, emphasizing conservation amid habitat loss and illegal collection pressures.Research and monitoring efforts

Monitoring efforts for the eastern box turtle (Terrapene carolina) have emphasized long-term population tracking, mark-recapture surveys, and telemetry to assess demographic trends and habitat use, revealing declines attributed to recruitment failure and habitat fragmentation.[72][73] At the Patuxent Research Refuge in Maryland, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) have conducted continuous monitoring since the 1940s, initially using manual tagging and later incorporating radio telemetry and digital data logging to track individual movements and survival rates across survey plots.[72] Serial censuses in 1945, 1955, 1965, and 1975 documented a pronounced population decline, with ongoing efforts evaluating detection probabilities through experimental field studies on turtle perception of surveyors.[72][74] Citizen science initiatives have expanded monitoring scale, particularly in fragmented landscapes. The Box Turtle Connection program in North Carolina employs mark-recapture methods across 39 sites to estimate population sizes, structures, and trends, integrating land cover data to correlate habitat types with occupancy.[75][76] In Virginia, the Department of Wildlife Resources recruits volunteers for distribution mapping and trend analysis to inform conservation strategies.[77] Similarly, the Northeast Turtle Conservation Network's protocol standardizes surveys for northeastern populations, recommending pre-management assessments and long-term site tracking to measure persistence.[78] Telemetry-based research has provided insights into post-rehabilitation outcomes and behavior. A 2023 pilot study attached radio transmitters to 16 rehabilitated eastern box turtles, monitoring health parameters and movements over extended periods to evaluate release success.[79] At Jug Bay Wetlands Sanctuary in Maryland, decades of monitoring have identified recruitment-mediated declines, with low juvenile survival linked to predation and habitat constraints.[73] These efforts collectively inform status assessments, such as the 2023 northeastern conservation plan, which prioritizes adaptive capacity through data on survival and habitat viability.[80]Habitat management and recovery initiatives

Habitat management for the eastern box turtle (Terrapene carolina carolina) emphasizes preserving contiguous woodland areas with diverse understory vegetation, as fragmentation from development reduces suitable foraging and overwintering sites.[36] Conservation strategies include protecting large public land tracts to buffer against edge effects and vehicular mortality, with recommendations to maintain canopy gaps for thermoregulation and leaf litter for humidity.[36] [65] Active enhancements involve planting native flora to support invertebrate prey and reducing pesticide applications, which can indirectly poison turtles via contaminated food chains.[81] Recovery initiatives coordinate through regional frameworks, such as the 2023 Conservation Plan for the Northeastern United States, which promotes adaptive management via collaboration among agencies, zoos, and landowners to address habitat loss and data gaps.[82] The AZA SAFE American Turtle Program supports box turtle efforts by funding habitat restoration and population assessments across North America, focusing on imperiled emydids.[83] Repatriation programs, like those by the Eastern Box Turtle Conservation Trust, prioritize recruiting juveniles from protected nests into native ranges and releasing rehabilitated individuals, with New Jersey's 2024 initiative returning 68 confiscated turtles to wild habitats after veterinary care.[84] [85] Enclosed assurance colonies, such as Reptile Conservation International's 50' x 100' fenced woodland replicate built in the 2010s, serve as models for ex-situ management while trialing reintroduction protocols.[86] These efforts underscore intentional interventions over passive protection to counter ongoing declines.[65]Human interactions

Pet trade and collection

Collection of common box turtles (Terrapene carolina) from the wild for the pet trade has historically relied on wild-caught individuals, as captive propagation remains limited due to the species' specialized dietary, thermal, and habitat requirements, which are difficult to replicate in enclosures.[87] Legal commercial collection peaked in certain areas before restrictions tightened; Oklahoma documented 9,719 box turtles (Terrapene spp., predominantly T. carolina and T. ornata) sold in 1991, after which state law ended such trade in 1992. U.S. export records show 55,341 box turtles shipped internationally from 1988 to 1993, with annual figures reaching 26,817 in 1992, primarily to Europe, Canada, and Japan, at prices of $10–$80 per turtle.[87] Illegal collection continues despite prohibitions, fueled by pet demand; undercover operations have revealed poaching networks, such as inquiries in Mississippi for 10,000–20,000 turtles annually, and seizures across 43 U.S. states involving over 24,000 freshwater turtles in 48 documented cases from 2010–2020, with Terrapene species implicated in 23 instances. Smuggling often targets Asian markets, where high values incentivize risks, though detected trade represents only a fraction of total activity.[87][88] Regulatory responses include bans on commercial take in over half of U.S. states, such as Florida, Illinois, and Virginia, alongside possession caps like South Carolina's limit of two T. carolina per person requiring registration since 2020. Federal oversight via the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service targets interstate and export violations, but enforcement challenges persist due to the species' terrestrial habits aiding undetected roadside harvesting.[87][89] Such removals impair population viability, given maturation times exceeding 10 years, annual clutch sizes of 3–5 eggs with high juvenile mortality, and limited dispersal, amplifying effects from even moderate collection alongside habitat loss and vehicles. Captive-held wild turtles often suffer elevated disease transmission, nutritional deficits, and stress, underscoring unsuitability for pet keeping and prompting recommendations against acquisition.[90][7]Cultural and symbolic roles

The common box turtle (Terrapene carolina) features prominently in Native American traditions across eastern North America, where its hinged shell was valued for practical and ceremonial purposes. Archaeological evidence from sites dating back over 3,000 years indicates that indigenous peoples, including those in the Midwest and Southeast, repurposed box turtle carapaces as rattles for music and rituals, often filling them with quartz crystals or pebbles to produce sound during dances and ceremonies.[91] Shells also served as containers, dippers, and scrapers among tribes such as the Cherokee, who referred to the turtle as "daksi" and integrated it into daily life for its durability.[92] Symbolically, the box turtle embodies patience, resilience, and longevity in these cultures, reflecting its slow pace, defensive shell retraction, and potential lifespan exceeding 100 years in the wild.[30] Many tribes, including Algonquian groups from which the genus name Terrapene derives (meaning "turtle"), revered turtles as guardians of the earth, associating them with stability, fertility, and the steady passage of time amid environmental pressures.[30][93] This mirrors broader indigenous views of turtles as symbols of perseverance, with the box turtle's ability to consume toxic mushrooms without harm further enhancing its perceived wisdom and self-sufficiency.[94] In modern contexts, the eastern box turtle (T. c. carolina), a subspecies, was designated Tennessee's state reptile in 1995 and North Carolina's in 1979, honoring its native resilience in forested habitats despite habitat fragmentation.[95] These designations underscore its cultural endurance, positioning it as a emblem of survival in regions where it has persisted through centuries of human alteration.[96]References

- https://www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/animals/[reptile](/page/Reptile)/teca/all.html