Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

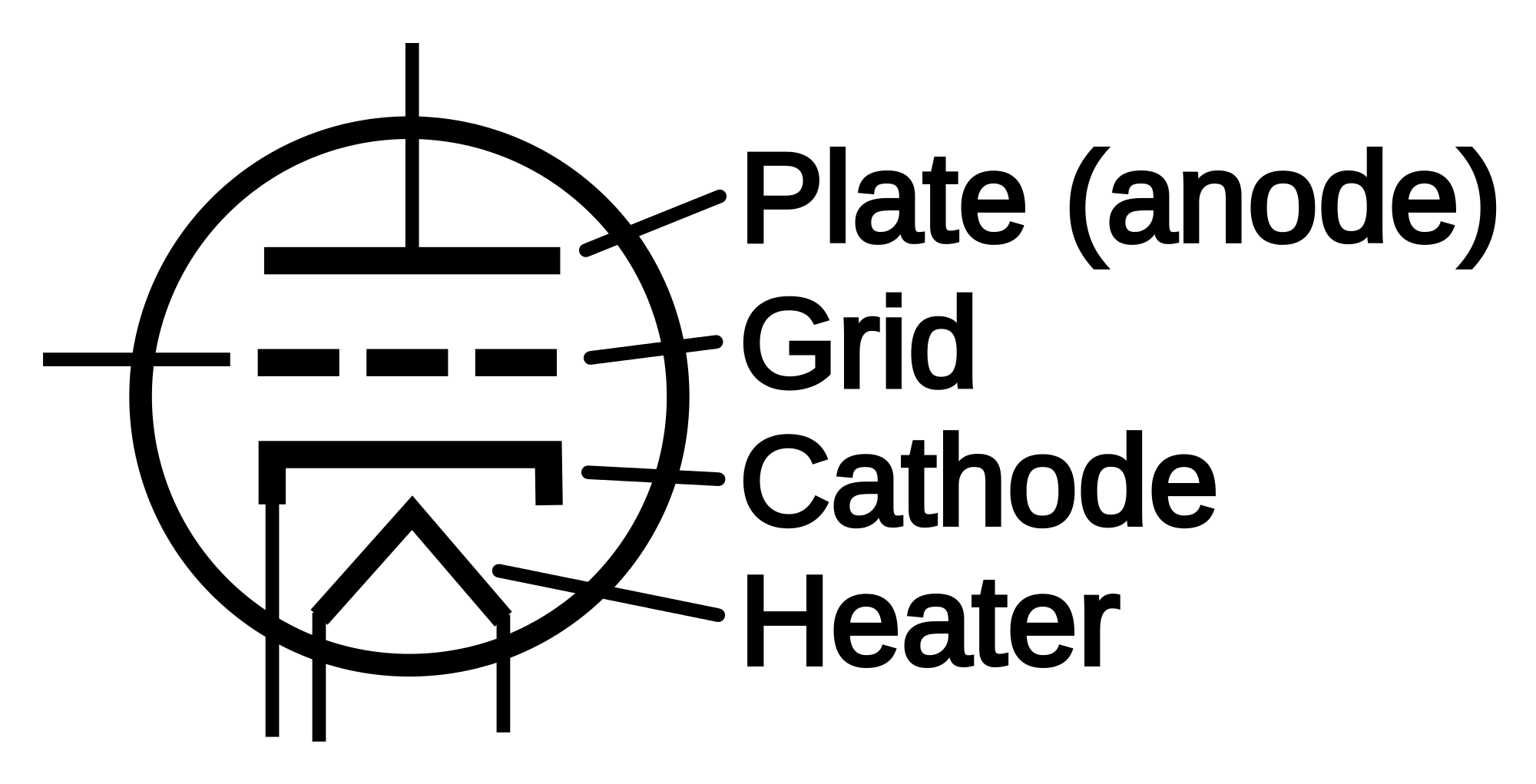

Control grid

View on Wikipedia

The control grid is an electrode used in amplifying thermionic valves (vacuum tubes) such as the triode, tetrode and pentode, used to control the flow of electrons from the cathode to the anode (plate) electrode. The control grid usually consists of a cylindrical screen or helix of fine wire surrounding the cathode, and is surrounded in turn by the anode. The control grid was invented by Lee De Forest, who in 1906 added a grid to the Fleming valve (thermionic diode) to create the first amplifying vacuum tube, the Audion (triode).

Operation

[edit]In a valve, the hot cathode emits negatively charged electrons, which are attracted to and captured by the anode, which is given a positive voltage by a power supply. The control grid between the cathode and anode functions as a "gate" to control the current of electrons reaching the anode. A more negative voltage on the grid will repel the electrons back toward the cathode so fewer get through to the anode. A less negative, or positive, voltage on the grid will allow more electrons through, increasing the anode current. A given change in grid voltage causes a proportional change in plate current, so if a time-varying voltage is applied to the grid, the plate current waveform will be a copy of the applied grid voltage.

A relatively small variation in voltage on the control grid causes a significantly large variation in anode current. The presence of a resistor in the anode circuit causes a large variation in voltage to appear at the anode. The variation in anode voltage can be much larger than the variation in grid voltage which caused it, and thus the tube can amplify, functioning as an amplifier.

Construction

[edit]

The grid in the first triode valve consisted of a zig-zag piece of wire placed between the filament and the anode. This quickly evolved into a helix or cylindrical screen of fine wire placed between a single strand filament (or later, a cylindrical cathode) and a cylindrical anode. The grid is usually made of a very thin wire that can resist high temperatures and is not prone to emitting electrons itself. Molybdenum alloy with a gold plating is frequently used. It is wound on soft copper sideposts, which are swaged over the grid windings to hold them in place. A 1950s variation is the frame grid, which winds very fine wire onto a rigid stamped metal frame. This allows the holding of very close tolerances, so the grid can be placed closer to the filament (or cathode).

Effects of grid position

[edit]By placing the control grid closer to the filament/cathode relative to the anode, a greater amplification results. This degree of amplification is referred to in valve data sheets as the amplification factor, or "mu". It also results in higher transconductance, which is a measure of the anode current change versus grid voltage change. The noise figure of a valve is inversely proportional to its transconductance; higher transconductance generally means lower noise figure. Lower noise can be very important when designing a radio or television receiver.

Multiple control grids

[edit]A valve can contain more than one control grid. The hexode contains two such grids, one for a received signal and one for the signal from a local oscillator. The valve's inherent non-linearity causes not only both original signals to appear in the anode circuit, but also the sum and difference of those signals. This can be exploited as a frequency-changer in superheterodyne receivers.

Grid variations

[edit]

A variation of the control grid is to produce the helix with a variable pitch. This gives the resultant valve a distinct non-linear characteristic.[1] This is often exploited in R.F. amplifiers where an alteration of the grid bias changes the mutual conductance and hence the gain of the device. This variation usually appears in the pentode form of the valve, where it is then called a variable-mu pentode or remote-cutoff pentode.

One of the principal limitations of the triode valve is that there is considerable capacitance between the grid and the anode (Cag). A phenomenon known as the Miller Effect causes the input capacitance of an amplifier to be the product of Cag and amplification factor of the valve. This, and the instability of an amplifier with tuned input and output when Cag is large can severely limit the upper operating frequency. These effects can be overcome by the addition of a screen grid, however in the later years of the tube era, constructional techniques were developed that rendered this 'parasitic capacitance' so low that triodes operating in the upper very high frequency (VHF) bands became possible. The Mullard EC91 operated at up to 250 MHz. The anode-grid capacitance of the EC91 is quoted in manufacturer's literature as 2.5 pF, which is higher than many other triodes of the era, while many triodes of the 1920s had figures which are strictly comparable, so there was no advance in this area. However, early screen-grid tetrodes of the 1920s, have Cag of only 1 or 2 fF, around a thousand times less. 'Modern' pentodes have comparable values of Cag. Triodes were used in VHF amplifiers in 'grounded-grid' configuration, a circuit arrangement which prevents Miller feedback.

References

[edit]- ^ Variable mu valves Archived 2007-03-10 at the Wayback Machine