Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Curved mirror

View on Wikipedia

A curved mirror is a mirror with a curved reflecting surface. The surface may be either convex (bulging outward) or concave (recessed inward). Most curved mirrors have surfaces that are shaped like part of a sphere, but other shapes are sometimes used in optical devices. The most common non-spherical type are parabolic reflectors, found in optical devices such as reflecting telescopes that need to image distant objects, since spherical mirror systems, like spherical lenses, suffer from spherical aberration. Distorting mirrors are used for entertainment. They have convex and concave regions that produce deliberately distorted images. They also provide highly magnified or highly diminished (smaller) images when the object is placed at certain distances. Convex mirrors are often used for security and safety in shops and parking lots.

Convex mirrors

[edit]

A convex mirror or diverging mirror is a curved mirror in which the reflective surface bulges towards the light source.[1] Convex mirrors reflect light outwards, therefore they are not used to focus light. Such mirrors always form a virtual image, since the focal point (F) and the centre of curvature (2F) are both imaginary points "inside" the mirror, that cannot be reached. As a result, images formed by these mirrors cannot be projected on a screen, since the image is inside the mirror. The image is smaller than the object, but gets larger as the object approaches the mirror.

A collimated (parallel) beam of light diverges (spreads out) after reflection from a convex mirror, since the normal to the surface differs at each spot on the mirror.

Uses

[edit]

The passenger-side mirror on a car is typically a convex mirror. In some countries, these are labeled with the safety warning "Objects in mirror are closer than they appear", to warn the driver of the convex mirror's distorting effects on distance perception. Convex mirrors are preferred in vehicles because they give an upright (not inverted), though diminished (smaller), image and because they provide a wider field of view as they are curved outwards.

These mirrors are often found in the hallways of various buildings (commonly known as "hallway safety mirrors"), including hospitals, hotels, schools, stores, and apartment buildings. They are usually mounted on a wall or ceiling where hallways intersect each other, or where they make sharp turns. They are useful for people to look at any obstruction they will face on the next hallway or after the next turn. They are also used on roads, driveways, and alleys to provide safety for road users where there is a lack of visibility, especially at curves and turns.[2]

Convex mirrors are used in some automated teller machines as a simple and handy security feature, allowing the users to see what is happening behind them. Similar devices are sold to be attached to ordinary computer monitors. Convex mirrors make everything seem smaller but cover a larger area of surveillance.

Round convex mirrors called Oeil de Sorcière (French for "sorcerer's eye") were a popular luxury item from the 15th century onwards, shown in many depictions of interiors from that time.[3] With 15th century technology, it was easier to make a regular curved mirror (from blown glass) than a perfectly flat one. They were also known as "bankers' eyes" because their wide field of vision was useful for security. Famous examples in art include the Arnolfini Portrait by Jan van Eyck and the left wing of the Werl Altarpiece by Robert Campin.[4]

Image

[edit]

The image on a convex mirror is always virtual (rays haven't actually passed through the image; their extensions do, like in a regular mirror), diminished (smaller), and upright (not inverted). As the object gets closer to the mirror, the image gets larger, until approximately the size of the object, when it touches the mirror. As the object moves away, the image diminishes in size and gets gradually closer to the focus, until it is reduced to a point in the focus when the object is at an infinite distance. These features make convex mirrors very useful: since everything appears smaller in the mirror, they cover a wider field of view than a normal plane mirror, so useful for looking at cars behind a driver's car on a road, watching a wider area for surveillance, etc.

| Object's position (S), focal point (F) |

Image | Diagram |

|---|---|---|

|

|

Concave mirrors

[edit]

A concave mirror, or converging mirror, has a reflecting surface that is recessed inward (away from the incident light). Concave mirrors reflect light inward to one focal point. They are used to focus light. Unlike convex mirrors, concave mirrors show different image types depending on the distance between the object and the mirror.

The mirrors are called "converging mirrors" because they tend to collect light that falls on them, refocusing parallel incoming rays toward a focus. This is because the light is reflected at different angles at different spots on the mirror as the normal to the mirror surface differs at each spot.

Uses

[edit]Concave mirrors are used in reflecting telescopes.[5] They are also used to provide a magnified image of the face for applying make-up or shaving.[6] In illumination applications, concave mirrors are used to gather light from a small source and direct it outward in a beam as in torches, headlamps and spotlights, or to collect light from a large area and focus it into a small spot, as in concentrated solar power. Concave mirrors are used to form optical cavities, which are important in laser construction. Some dental mirrors use a concave surface to provide a magnified image. The mirror landing aid system of modern aircraft carriers also uses a concave mirror.

Image

[edit]| Object's position (S), focal point (F) |

Nature of Image | Diagram |

|---|---|---|

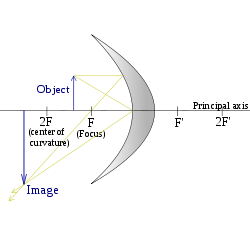

| (Object between focal point and mirror) |

|

|

| (Object at focal point) |

| |

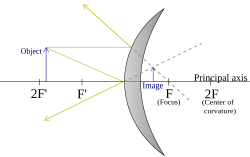

(Object between focus and centre of curvature) |

|

|

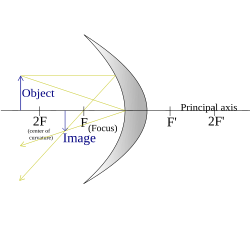

| (Object at centre of curvature) |

|

|

(Object beyond centre of curvature) |

|

|

Mirror shape

[edit]Most curved mirrors have a spherical profile.[7] These are the simplest to make, and it is the best shape for general-purpose use. Spherical mirrors, however, suffer from spherical aberration—parallel rays reflected from such mirrors do not focus to a single point. For parallel rays, such as those coming from a very distant object, a parabolic reflector can do a better job. Such a mirror can focus incoming parallel rays to a much smaller spot than a spherical mirror can. A toroidal reflector is a form of parabolic reflector which has a different focal distance depending on the angle of the mirror.

Analysis

[edit]Mirror equation, magnification, and focal length

[edit]The Gaussian mirror equation, also known as the mirror and lens equation, relates the object distance and image distance to the focal length :[2]

- .

The sign convention used here is that the focal length is positive for concave mirrors and negative for convex ones, and and are positive when the object and image are in front of the mirror, respectively. (They are positive when the object or image is real.)[2]

For convex mirrors, if one moves the term to the right side of the equation to solve for , then the result is always a negative number, meaning that the image distance is negative—the image is virtual, located "behind" the mirror. This is consistent with the behavior described above.

For concave mirrors, whether the image is virtual or real depends on how large the object distance is compared to the focal length. If the term is larger than the term, then is positive and the image is real. Otherwise, the term is negative and the image is virtual. Again, this validates the behavior described above.

The magnification of a mirror is defined as the height of the image divided by the height of the object:

- .

By convention, if the resulting magnification is positive, the image is upright. If the magnification is negative, the image is inverted (upside down).

Ray tracing

[edit]The image location and size can also be found by graphical ray tracing, as illustrated in the figures above. A ray drawn from the top of the object to the mirror surface vertex (where the optical axis meets the mirror) will form an angle with the optical axis. The reflected ray has the same angle to the axis, but on the opposite side (See Specular reflection).

A second ray can be drawn from the top of the object, parallel to the optical axis. This ray is reflected by the mirror and passes through its focal point. The point at which these two rays meet is the image point corresponding to the top of the object. Its distance from the optical axis defines the height of the image, and its location along the axis is the image location. The mirror equation and magnification equation can be derived geometrically by considering these two rays. A ray that goes from the top of the object through the focal point can be considered instead. Such a ray reflects parallel to the optical axis and also passes through the image point corresponding to the top of the object.

Ray transfer matrix of spherical mirrors

[edit]The mathematical treatment is done under the paraxial approximation, meaning that under the first approximation a spherical mirror is a parabolic reflector. The ray matrix of a concave spherical mirror is shown here. The element of the matrix is , where is the focal point of the optical device.

Boxes 1 and 3 feature summing the angles of a triangle and comparing to π radians (or 180°). Box 2 shows the Maclaurin series of up to order 1. The derivations of the ray matrices of a convex spherical mirror and a thin lens are very similar.

See also

[edit]- Alhazen's problem (reflection from a spherical mirror)

- Anamorphosis

- Concentrated solar power - a method of solar power generation using curved mirrors or arrays of mirrors

- Dioptre

- List of telescope parts and construction

- Optical power

References

[edit]- ^ Nayak, Sanjay K.; Bhuvana, K.P. (2012). Engineering Physics. New Delhi: Tata McGraw-Hill Education. p. 6.4. ISBN 9781259006449.

- ^ a b c Hecht, Eugene (1987). "5.4.3". Optics (2nd ed.). Addison Wesley. pp. 160–1. ISBN 0-201-11609-X.

- ^ Venice Botteghe: Antiques, Bijouterie, Coffee, Cakes, Carpet, Glass Archived 2017-03-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lorne Campbell, National Gallery Catalogues (new series): The Fifteenth Century Netherlandish Paintings, pp. 178-179, 188-189, 1998, ISBN 1-85709-171-X

- ^ Joshi, Dhiren M. Living Science Physics 10. Ratna Sagar. ISBN 9788183322904. Archived from the original on 2018-01-18.

- ^ Sura's Year Book 2006 (English). Sura Books. ISBN 9788172541248. Archived from the original on 2018-01-18.

- ^ Al-Azzawi, Abdul (2006-12-26). Light and Optics: Principles and Practices. CRC Press. ISBN 9780849383144. Archived from the original on 2018-01-18.

External links

[edit]- Java applets to explore ray tracing for curved mirrors

- Concave mirrors — real images, Molecular Expressions Optical Microscopy Primer

- Spherical mirrors, online physics lab

- "Grinding the World's Largest Mirror" Popular Science, December 1935

Curved mirror

View on GrokipediaFundamentals of Curved Mirrors

Definition and Basic Principles

A curved mirror is a reflective surface with a curvature that deviates from flatness, causing incident light rays to converge or diverge upon reflection, unlike the parallel reflection produced by a plane mirror.[3] These mirrors are typically portions of a sphere, with the reflecting surface either on the inner (concave) or outer (convex) side, enabling applications in optics by altering the paths of light rays based on the surface's geometry.[3] The legend attributes early use of curved mirrors to Archimedes in the 3rd century BCE, who reportedly employed concave mirrors as burning devices to focus sunlight during the siege of Syracuse by concentrating solar rays to ignite invading ships.[4] Significant advancements occurred in the 17th century, particularly through Isaac Newton's development of the reflecting telescope in 1668, which utilized a concave mirror to gather and focus light, addressing chromatic aberration issues in refractive telescopes.[5] The fundamental principle governing reflection in curved mirrors is the law of reflection, which states that the incident ray, the reflected ray, and the normal to the surface at the point of incidence all lie in the same plane, with the angle of incidence equaling the angle of reflection.[6] In curved mirrors, this law applies locally at each point on the surface, where the normal is perpendicular to the tangent at that point; the curvature causes rays parallel to the principal axis—a line passing through the center of the sphere and the mirror's vertex (or pole, the geometric center where the axis meets the surface)—to reflect toward or away from a common focal point, qualitatively bending the ray paths to either converge (in concave mirrors) or diverge (in convex mirrors).[3] The center of curvature is the central point of the sphere from which the mirror is derived, defining the mirror's overall shape.[3] In contrast to plane mirrors, which produce virtual, upright images of the same size as the object and located at an equal distance behind the mirror, curved mirrors modify image properties such that the size, orientation, and position vary depending on the object's distance and the mirror's curvature radius.[7] This deviation arises because the non-uniform normals across the curved surface redirect rays non-parallelly, allowing for focused or spread-out reflections that plane mirrors cannot achieve.[6]Spherical Mirror Geometry

A spherical mirror consists of a portion of a sphere's surface that acts as a reflector, approximating the behavior of more complex curved mirrors in basic optical analysis. The reflecting surface can face inward toward the center of the sphere, forming a concave mirror, or outward away from the center, forming a convex mirror.[8][6] The radius of curvature is defined as the distance from the mirror's vertex—the point where the mirror intersects the principal axis—to the center of curvature, which is the center of the sphere from which the mirror segment is derived.[8] In the standard Cartesian sign convention for optics, is positive when the center of curvature lies on the same side as the incident light (for concave mirrors) and negative when it lies on the opposite side (for convex mirrors).[9] The focal length , which locates the focal point where parallel rays along the principal axis converge or appear to diverge after reflection, is related to the radius of curvature by the equation This relationship arises from the geometry of reflection on a spherical surface: for rays parallel to the principal axis, the law of reflection ensures they intersect at a point halfway between the vertex and the center of curvature.[10][11] Analysis of spherical mirrors relies on the paraxial approximation, which assumes incident rays make small angles with the principal axis, enabling simplified trigonometric relations and the neglect of higher-order terms in the reflection equations.[8] A key limitation of this approximation in spherical mirrors is spherical aberration, where rays farther from the principal axis focus at different points than paraxial rays, resulting in imperfect image formation.[12]Types of Curved Mirrors

Convex Mirrors

A convex mirror features a reflective surface that curves outward, bulging toward the incoming light and thereby acting as a diverging mirror. This outward curvature distinguishes it from concave mirrors, where the surface indents inward, and results in the reflection of light rays away from a common point. The mirror's spherical geometry is characterized by a positive radius of curvature measured from the vertex to the center of curvature behind the surface.[9][13] Upon reflection from a convex mirror, parallel incident rays diverge in directions that, when traced backward, appear to originate from a virtual focal point situated behind the mirror. This diverging behavior contrasts with the converging action of concave mirrors and ensures that no real image can form in front of the mirror. The focal point lies at half the radius of curvature from the mirror's vertex.[14][15] In standard Cartesian sign conventions for optics, the focal length and radius of curvature of a convex mirror are assigned negative values, reflecting the virtual nature of the focal point relative to incident light from the left. This convention facilitates consistent calculations across mirror types, where .[1][16] Convex mirrors offer a wider angle of reflection compared to flat mirrors, enabling observation over a broader field without the need for head movement and thereby minimizing obscured areas in the view. They are commonly constructed using silvered glass substrates with protective coatings or polished metal surfaces to ensure durability and high reflectivity, with typical radii of curvature ranging from 10 to 50 cm for laboratory and optical instrument applications.[17][18]Concave Mirrors

A concave mirror possesses an inward-curving reflective surface that faces toward the incident light, enabling it to act as a converging optical element.[13] This curvature causes incoming light rays to bend inward upon reflection, distinguishing it from flat or outward-curving mirrors. The reflective coating is applied to the inner, concave side of the surface, which is typically spherical in basic designs.[6] In a concave mirror, rays of light incident parallel to the principal axis—the line passing through the mirror's center and perpendicular to its surface—converge after reflection to a real focal point situated in front of the mirror.[19] This focal point lies midway along the radius to the center of curvature, the point on the principal axis where the sphere of which the mirror is a segment would have its center.[16] The converging nature arises from the geometry of the curved surface, which directs parallel rays toward a common intersection. Concave mirrors can produce enlarged real images under specific object placements, such as when the object is positioned between the focal point and the center of curvature.[16] In standard optics sign conventions, the focal length and radius of curvature for concave mirrors are assigned positive values, reflecting their converging behavior relative to the incident light direction.[20] This convention facilitates consistent calculations in optical analysis, treating the mirror's front side as the reference for positive distances. For many optical instruments and laboratory setups, the radius of curvature of concave mirrors typically ranges from 20 to 100 cm, which proportionally influences the focal length since it is half the radius.[21] Such dimensions are common in educational kits and small-scale devices, balancing compactness with effective light convergence.[22]Non-Spherical Mirrors

Spherical mirrors suffer from spherical aberration, where peripheral rays parallel to the optical axis focus at different points from paraxial rays, leading to blurred images and reduced sharpness for extended objects.[8][12] This limitation arises because the spherical surface approximates a paraboloid only near the axis, causing off-axis rays to converge short of the paraxial focal point.[8] To address these issues, non-spherical mirrors employ conic section profiles that eliminate spherical aberration for specific ray configurations. Parabolic mirrors, formed as paraboloids of revolution, direct all parallel incident rays—such as those from distant sources—precisely to a single focal point without aberration, making them superior for applications requiring sharp focus.[23] This property stems from the parabola's geometry, where the reflective surface ensures equal path lengths for rays to the focus after reflection.[23] Elliptical mirrors, shaped from ellipsoid segments, possess two foci and reflect rays originating from one focus directly to the other, enabling efficient light transfer in compact systems without spherical aberration for that configuration.[24] Hyperbolic mirrors, conversely, focus diverging rays from a virtual focus to a real one, often used as secondary elements to correct off-axis aberrations in composite designs like Cassegrain telescopes.[25] The development of parabolic mirrors traces to the 17th century, when James Gregory proposed a reflecting telescope with a parabolic primary to avoid spherical aberration, predating practical implementations.[26] Laurent Cassegrain later described a configuration pairing a parabolic primary with a hyperbolic secondary, advancing folded optical paths for telescopes.[27] In modern contexts, parabolic mirrors underpin satellite dishes, where they concentrate microwave signals from geostationary satellites onto a receiver at the focal point for amplified reception.[28]| Mirror Type | Spherical Aberration for Parallel Incident Rays | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Spherical | Present; peripheral rays focus short of paraxial point | Simple fabrication |

| Parabolic | Absent; all rays converge at single focal point | Aberration-free focusing for collimated light[23] |