Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Reflecting telescope

View on Wikipedia

A reflecting telescope (also called a reflector) is a telescope that uses a single or a combination of curved mirrors that reflect light and form an image. The reflecting telescope was invented in the 17th century by Isaac Newton as an alternative to the refracting telescope which, at that time, was a design that suffered from severe chromatic aberration. Although reflecting telescopes produce other types of optical aberrations, it is a design that allows for very large diameter objectives. Almost all of the major telescopes used in astronomy research are reflectors. Many variant forms are in use and some employ extra optical elements to improve image quality or place the image in a mechanically advantageous position. Since reflecting telescopes use mirrors, the design is sometimes referred to as a catoptric telescope.[1]

From the time of Newton to the 19th century, the mirror itself was made of metal – usually speculum metal. This type included Newton's first designs and the largest telescope of the 19th century, the Leviathan of Parsonstown with a 6 feet (1.8 m) wide metal mirror. In the 19th century a new method using a block of glass coated with very thin layer of silver began to become more popular by the turn of the century. Common telescopes which led to the Crossley and Harvard reflecting telescopes, which helped establish a better reputation for reflecting telescopes as the metal mirror designs were noted for their drawbacks. Chiefly the metal mirrors only reflected about 2⁄3 of the light and the metal would tarnish. After multiple polishings and tarnishings, the mirror could lose its precise figuring needed.

Reflecting telescopes became extraordinarily popular for astronomy and many famous telescopes, such as the Hubble Space Telescope, and popular amateur models use this design. In addition, the reflection telescope principle was applied to other electromagnetic wavelengths, and for example, X-ray telescopes also use the reflection principle to make image-forming optics.

History

[edit]

The idea that curved mirrors behave like lenses dates back at least to Alhazen's 11th century treatise on optics, works that had been widely disseminated in Latin translations in early modern Europe.[3] Soon after the invention of the refracting telescope, Galileo Galilei, Giovanni Francesco Sagredo, and others, spurred on by their knowledge of the principles of curved mirrors, discussed the idea of building a telescope using a mirror as the image forming objective.[4] There were reports that the Bolognese Cesare Caravaggi had constructed one around 1626 and the Italian professor Niccolò Zucchi, in a later work, wrote that he had experimented with a concave bronze mirror in 1616, but said it did not produce a satisfactory image.[4] The potential advantages of using parabolic mirrors, primarily reduction of spherical aberration with no chromatic aberration, led to many proposed designs for reflecting telescopes. These included one by James Gregory, published in 1663. In 1673, experimental scientist Robert Hooke was able to build this type of telescope, which became known as the Gregorian telescope.[5][6][7]

Five years after Gregory designed his telescope and five years before Hooke built the first such Gregorian telescope, Isaac Newton in 1668 built his own reflecting telescope, which is considered the first reflecting telescope, as previous designs were never put into practice or ended in failure when attempted.[6][8][9] Newton's telescope used a spherically ground metal primary mirror and a small diagonal mirror in an optical configuration that has come to be known as the Newtonian telescope.

Despite the theoretical advantages of the reflector design, the difficulty of construction and the poor performance of the speculum metal mirrors being used at the time meant it took over 100 years for them to become popular. Many of the advances in reflecting telescopes included the perfection of parabolic mirror fabrication in the 18th century,[10] silver coated glass mirrors in the 19th century (built by Léon Foucault in 1858),[11] long-lasting aluminum coatings in the 20th century,[12] segmented mirrors to allow larger diameters, and active optics to compensate for gravitational deformation. A mid-20th century innovation was catadioptric telescopes such as the Schmidt camera, which use both a spherical mirror and a lens (called a corrector plate) as primary optical elements, mainly used for wide-field imaging without spherical aberration.

The late 20th century has seen the development of adaptive optics and lucky imaging to overcome the problems of seeing, and reflecting telescopes are ubiquitous on space telescopes and many types of spacecraft imaging devices.

Technical considerations

[edit]

A curved primary mirror is the reflector telescope's basic optical element that creates an image at the focal plane. The distance from the mirror to the focal plane is called the focal length. Film or a digital sensor may be located here to record the image, or a secondary mirror may be added to modify the optical characteristics and/or redirect the light to film, digital sensors, or an eyepiece for visual observation.

The primary mirror in most modern telescopes is composed of a solid glass cylinder whose front surface has been ground to a spherical or parabolic shape. A thin layer of aluminum is vacuum deposited onto the mirror, forming a highly reflective first surface mirror.

Some telescopes use primary mirrors which are made differently. Molten glass is rotated to make its surface paraboloidal, and is kept rotating while it cools and solidifies. (See Rotating furnace.) The resulting mirror shape approximates a desired paraboloid shape that requires minimal grinding and polishing to reach the exact figure needed.[13]

Optical errors

[edit]Reflecting telescopes, just like any other optical system, do not produce "perfect" images. The need to image objects at distances up to infinity, view them at different wavelengths of light, along with the requirement to have some way to view the image the primary mirror produces, means there is always some compromise in a reflecting telescope's optical design.

Because the primary mirror focuses light to a common point in front of its own reflecting surface almost all reflecting telescope designs have a secondary mirror, film holder, or detector near that focal point partially obstructing the light from reaching the primary mirror. Not only does this cause some reduction in the amount of light the system collects, it also causes a loss in contrast in the image due to diffraction effects of the obstruction as well as diffraction spikes caused by most secondary support structures.[14][15]

The use of mirrors avoids chromatic aberration but they produce other types of aberrations. A simple spherical mirror cannot bring light from a distant object to a common focus since the reflection of light rays striking the mirror near its edge do not converge with those that reflect from nearer the center of the mirror, a defect called spherical aberration. To avoid this problem most reflecting telescopes use parabolic shaped mirrors, a shape that can focus all the light to a common focus. Parabolic mirrors work well with objects near the center of the image they produce, (light traveling parallel to the mirror's optical axis), but towards the edge of that same field of view they suffer from off axis aberrations:[16][17]

- Coma – an aberration where point sources (stars) at the center of the image are focused to a point but typically appears as "comet-like" radial smudges that get worse towards the edges of the image.

- Field curvature – The best image plane is in general curved, which may not correspond to the detector's shape and leads to a focus error across the field. It is sometimes corrected by a field flattening lens.

- Astigmatism – an azimuthal variation of focus around the aperture causing point source images off-axis to appear elliptical. Astigmatism is not usually a problem in a narrow field of view, but in a wide field image it gets rapidly worse and varies quadratically with field angle.

- Distortion – Distortion does not affect image quality (sharpness) but does affect object shapes. It is sometimes corrected by image processing.

There are reflecting telescope designs that use modified mirror surfaces (such as the Ritchey–Chrétien telescope) or some form of correcting lens (such as catadioptric telescopes) that correct some of these aberrations.

Use in astronomical research

[edit]

Nearly all large research-grade astronomical telescopes are reflectors. There are several reasons for this:

- Reflectors work in a wider spectrum of light since certain wavelengths are absorbed when passing through glass elements like those found in a refractor or in a catadioptric telescope.

- In a lens the entire volume of material has to be free of imperfection and inhomogeneities, whereas in a mirror, only one surface has to be perfectly polished.

- Light of different wavelengths travels through a medium other than vacuum at different speeds. This causes chromatic aberration. Reducing this to acceptable levels usually involves a combination of two or three aperture sized lenses (see achromat and apochromat for more details). The cost of such systems therefore scales significantly with aperture size. An image obtained from a mirror does not suffer from chromatic aberration to begin with, and the cost of the mirror scales much more modestly with its size.

- There are structural problems involved in manufacturing and manipulating large-aperture lenses. Since a lens can only be held in place by its edge, the center of a large lens will sag due to gravity, distorting the image it produces. The largest practical lens size in a refracting telescope is around 1 meter.[18] In contrast, a mirror can be supported by the whole side opposite its reflecting face, allowing for reflecting telescope designs that can overcome gravitational sag. The largest reflector designs currently exceed 10 meters in diameter.

Reflecting telescope designs

[edit]Gregorian

[edit]

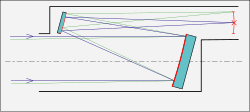

The Gregorian telescope, described by Scottish astronomer and mathematician James Gregory in his 1663 book Optica Promota, employs a concave secondary mirror that reflects the image back through a hole in the primary mirror. This produces an upright image, useful for terrestrial observations. Some small spotting scopes are still built this way. There are several large modern telescopes that use a Gregorian configuration such as the Vatican Advanced Technology Telescope, the Magellan telescopes, the Large Binocular Telescope, and the Giant Magellan Telescope.

Newtonian

[edit]

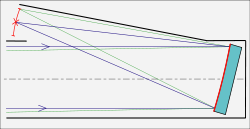

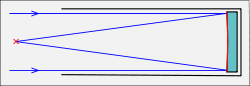

The Newtonian telescope was the first successful reflecting telescope, completed by Isaac Newton in 1668. It usually has a paraboloid primary mirror but at focal ratios of about f/10 or longer a spherical primary mirror can be sufficient for high visual resolution. A flat secondary mirror reflects the light to a focal plane at the side of the top of the telescope tube. It is one of the simplest and least expensive designs for a given size of primary, and is popular with amateur telescope makers as a home-build project.

The Cassegrain design and its variations

[edit]

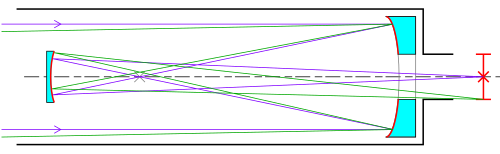

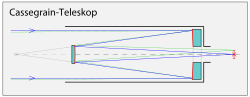

The Cassegrain telescope (sometimes called the "Classic Cassegrain") was first published in a 1672 design attributed to Laurent Cassegrain. It has a parabolic primary mirror, and a hyperbolic secondary mirror that reflects the light back down through a hole in the primary. The folding and diverging effect of the secondary mirror creates a telescope with a long focal length while having a short tube length.

Ritchey–Chrétien

[edit]The Ritchey–Chrétien telescope, invented by George Willis Ritchey and Henri Chrétien in the early 1910s, is a specialized Cassegrain reflector which has two hyperbolic mirrors (instead of a parabolic primary). It is free of coma and spherical aberration at a nearly flat focal plane if the primary and secondary curvature are properly figured, making it well suited for wide field and photographic observations.[19] Almost every professional reflector telescope in the world is of the Ritchey–Chrétien design.

Three-mirror anastigmat

[edit]Including a third curved mirror allows correction of the remaining distortion, astigmatism, from the Ritchey–Chrétien design. This allows much larger fields of view.

Dall–Kirkham

[edit]

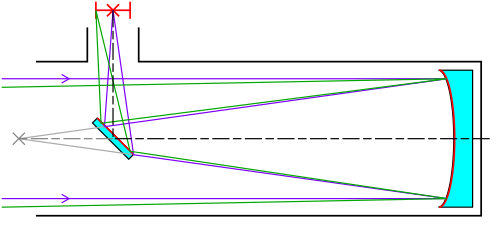

The Dall–Kirkham Cassegrain telescope's design was created by Horace Dall in 1928 and took on the name in an article published in Scientific American in 1930 following discussion between amateur astronomer Allan Kirkham and Albert G. Ingalls, the magazine editor at the time. It uses a concave elliptical primary mirror and a convex spherical secondary. While this system is easier to grind than a classic Cassegrain or Ritchey–Chrétien system, it does not correct for off-axis coma. Field curvature is actually less than a classical Cassegrain. Because this is less noticeable at longer focal ratios, Dall–Kirkhams are seldom faster than f/15.

Off-axis designs

[edit]There are several designs that try to avoid obstructing the incoming light by eliminating the secondary or moving any secondary element off the primary mirror's optical axis, commonly called off-axis optical systems.

Herschelian

[edit]The Herschelian reflector is named after William Herschel, who used this design to build very large telescopes including the 40-foot telescope in 1789. In the Herschelian reflector the primary mirror is tilted so the observer's head does not block the incoming light. Although this introduces geometrical aberrations, Herschel employed this design to avoid the use of a Newtonian secondary mirror since the speculum metal mirrors of that time tarnished quickly and could only achieve 60% reflectivity.[20]

Schiefspiegler

[edit]A variant of the Cassegrain, the Schiefspiegler telescope ("skewed" or "oblique reflector") uses tilted mirrors to avoid the secondary mirror casting a shadow on the primary. However, while eliminating diffraction patterns this leads to an increase in coma and astigmatism. These defects become manageable at large focal ratios — most Schiefspieglers use f/15 or longer, which tends to restrict useful observations to objects which fit in a moderate field of view. A 6" (150mm) f/15 telescope offers a maximum 0.75 degree field of view using 1.25" eyepieces. A number of variations are common, with varying numbers of mirrors of different types. The Kutter (named after its inventor Anton Kutter) style uses a single concave primary, a convex secondary and a plano-convex lens between the secondary mirror and the focal plane, when needed (this is the case of the catadioptric Schiefspiegler). One variation of a multi-schiefspiegler uses a concave primary, convex secondary and a parabolic tertiary. One of the interesting aspects of some Schiefspieglers is that one of the mirrors can be involved in the light path twice — each light path reflects along a different meridional path.

Stevick-Paul

[edit]Stevick-Paul telescopes[21] are off-axis versions of Paul 3-mirror systems[22] with an added flat diagonal mirror. A convex secondary mirror is placed just to the side of the light entering the telescope, and positioned afocally so as to send parallel light on to the tertiary. The concave tertiary mirror is positioned exactly twice as far to the side of the entering beam as was the convex secondary, and its own radius of curvature distant from the secondary. Because the tertiary mirror receives parallel light from the secondary, it forms an image at its focus. The focal plane lies within the system of mirrors, but is accessible to the eye with the inclusion of a flat diagonal. The Stevick-Paul configuration results in all optical aberrations totaling zero to the third-order, except for the Petzval surface which is gently curved.

Yolo

[edit]The Yolo was developed by Arthur S. Leonard in the mid-1960s.[23] Like the Schiefspiegler, it is an unobstructed, tilted reflector telescope. The original Yolo consists of a primary and secondary concave mirror, with the same curvature, and the same tilt to the main axis. Most Yolos use toroidal reflectors. The Yolo design eliminates coma, but leaves significant astigmatism, which is reduced by deformation of the secondary mirror by some form of warping harness, or alternatively, polishing a toroidal figure into the secondary. Like Schiefspieglers, many Yolo variations have been pursued. The needed amount of toroidal shape can be transferred entirely or partially to the primary mirror. In large focal ratios optical assemblies, both primary and secondary mirror can be left spherical and a spectacle correcting lens is added between the secondary mirror and the focal plane (catadioptric Yolo). The addition of a convex, long focus tertiary mirror leads to Leonard's Solano configuration. The Solano telescope doesn't contain any toric surfaces.

Liquid-mirror telescopes

[edit]One design of telescope uses a rotating mirror consisting of a liquid metal in a tray that is spun at constant speed. As the tray spins, the liquid forms a paraboloidal surface of essentially unlimited size. This allows making very big telescope mirrors (over 6 metres), but they are limited to use by zenith telescopes.

Focal planes

[edit]Prime focus

[edit]

In a prime focus design no secondary optics are used, the image is accessed at the focal point of the primary mirror. At the focal point is some type of structure for holding a film plate or electronic detector. In the past, in very large telescopes, an observer would sit inside the telescope in an "observing cage" to directly view the image or operate a camera.[24] Nowadays CCD cameras allow for remote operation of the telescope from almost anywhere in the world. The space available at prime focus is severely limited by the need to avoid obstructing the incoming light.[25]

Radio telescopes often have a prime focus design. The mirror is replaced by a metal surface for reflecting radio waves, and the observer is an antenna.

Cassegrain focus

[edit]

For telescopes built to the Cassegrain design or other related designs, the image is formed behind the primary mirror, at the focal point of the secondary mirror. An observer views through the rear of the telescope, or a camera or other instrument is mounted on the rear. Cassegrain focus is commonly used for amateur telescopes or smaller research telescopes. However, for large telescopes with correspondingly large instruments, an instrument at Cassegrain focus must move with the telescope as it slews; this places additional requirements on the strength of the instrument support structure, and potentially limits the movement of the telescope in order to avoid collision with obstacles such as walls or equipment inside the observatory.

Nasmyth and coudé focus

[edit]

Nasmyth

[edit]The Nasmyth design is similar to the Cassegrain except the light is not directed through a hole in the primary mirror; instead, a third mirror reflects the light to the side of the telescope to allow for the mounting of heavy instruments. This is a very common design in large research telescopes.[26]

Coudé

[edit]Adding further optics to a Nasmyth-style telescope to deliver the light (usually through the declination axis) to a fixed focus point that does not move as the telescope is reoriented gives a coudé focus (from the French word for elbow).[27] The coudé focus gives a narrower field of view than a Nasmyth focus[27] and is used with very heavy instruments that do not need a wide field of view. One such application is high-resolution spectrographs that have large collimating mirrors (ideally with the same diameter as the telescope's primary mirror) and very long focal lengths. Such instruments could not withstand being moved, and adding mirrors to the light path to form a coudé train, diverting the light to a fixed position to such an instrument housed on or below the observing floor (and usually built as an unmoving integral part of the observatory building) was the only option. The 60-inch Hale telescope (1.5 m), Hooker Telescope, 200-inch Hale Telescope, Shane Telescope, and Harlan J. Smith Telescope all were built with coudé foci instrumentation. The development of echelle spectrometers allowed high-resolution spectroscopy with a much more compact instrument, one which can sometimes be successfully mounted on the Cassegrain focus. Since inexpensive and adequately stable computer-controlled alt-az telescope mounts were developed in the 1980s, the Nasmyth design has generally supplanted the coudé focus for large telescopes.

Fibre-fed spectrographs

[edit]For instruments requiring very high stability, or that are very large and cumbersome, it is desirable to mount the instrument on a rigid structure, rather than moving it with the telescope. Whilst transmission of the full field of view would require a standard coudé focus, spectroscopy typically involves the measurement of only a few discrete objects, such as stars or galaxies. It is therefore feasible to collect light from these objects with optical fibers at the telescope, placing the instrument at an arbitrary distance from the telescope. Examples of fiber-fed spectrographs include the planet-hunting spectrographs HARPS[28] or ESPRESSO.[29]

Additionally, the flexibility of optical fibers allow light to be collected from any focal plane; for example, the HARPS spectrograph utilises the Cassegrain focus of the ESO 3.6 m Telescope,[28] whilst the Prime Focus Spectrograph is connected to the prime focus of the Subaru telescope.[30]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Freeform catoptric telescope with pointing and nodding capabilities". European Space Agency. European Space Agency. Retrieved 23 December 2024.

- ^ Henry C. King (1955). The History of the Telescope. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-486-43265-6. Retrieved 2013-08-01.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Fred Watson (2007). Stargazer: The Life and Times of the Telescope. Allen & Unwin. p. 108. ISBN 978-1-74176-392-8.

- ^ a b Fred Watson (2007). Stargazer: The Life and Times of the Telescope. Allen & Unwin. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-74176-392-8.

- ^ Fred Watson (2007). Stargazer: The Life and Times of the Telescope. Allen & Unwin. p. 117. ISBN 978-1-74176-392-8.

- ^ a b Henry C. King (1955). The History of the Telescope. Richard Griffin & Co. p. 68–72. ISBN 978-0-486-43265-6.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ "Explore, National Museums Scotland". Archived from the original on 2017-01-17. Retrieved 2016-11-15.

- ^ A. Rupert Hall (1996). Isaac Newton: Adventurer in Thought. Cambridge University Press. p. 67–68. ISBN 978-0-521-56669-8.

- ^ Rowlands, Peter (2017). Newton and the Great World System. World Scientific Publishing. p. 245. doi:10.1142/q0108. ISBN 978-1-78634-372-7.

- ^ Parabolic mirrors were used much earlier, but James Short perfected their construction. See "Reflecting Telescopes (Newtonian Type)". Astronomy Department, University of Michigan. Archived from the original on 2009-01-31.

- ^ Lequeux, James (2017-01-01). "The Paris Observatory has 350 years". L'Astronomie. 131: 28–37. Bibcode:2017LAstr.131a..28L. ISSN 0004-6302.

- ^ Silvering on a reflecting telescope was introduced by Léon Foucault in 1857, see madehow.com - Inventor Biographies - Jean-Bernard-Léon Foucault Biography (1819–1868), and the adoption of long lasting aluminized coatings on reflector mirrors in 1932. Bakich sample pages Chapter 2, Page 3 "John Donavan Strong, a young physicist at the California Institute of Technology, was one of the first to coat a mirror with aluminum. He did it by thermal vacuum evaporation. The first mirror he aluminized, in 1932, is the earliest known example of a telescope mirror coated by this technique."

- ^ Ray Villard; Leonello Calvetti; Lorenzo Cecchi (2001). Large Telescopes: Inside and Out. The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-8239-6110-8.

- ^ Rodger W. Gordon, "Central Obstructions and their effect on image contrast" brayebrookobservatory.org

- ^ "Obstruction" in optical instruments

- ^ Richard Fitzpatrick, Spherical Mirrors, farside.ph.utexas.edu

- ^ "Vik Dhillon, reflectors, vikdhillon.staff.shef.ac.uk". Archived from the original on 2010-05-05. Retrieved 2010-04-06.

- ^ Stan Gibilisco (2002). Physics Demystified. Mcgraw-hill. p. 515. ISBN 978-0-07-138201-4.

- ^ Sacek, Vladimir (July 14, 2006). "8.2.2 Classical and aplanatic two-mirror systems". Notes on AMATEUR TELESCOPE OPTICS. Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- ^ catalogue.museogalileo.it - Institute and Museum of the History of Science - Florence, Italy, Telescope, glossary

- ^ "Stevick-Paul Telescopes by Dave Stevick". Archived from the original on 2021-11-17. Retrieved 2014-12-26.

- ^ Paul, M. (1935). "Systèmes correcteurs pour réflecteurs astronomiques". Revue d'Optique Théorique et Instrumentale. 14 (5): 169–202.

- ^ Arthur S. Leonard THE YOLO REFLECTOR

- ^ W. Patrick McCray (2004). Giant Telescopes: Astronomical Ambition and the Promise of Technology. Harvard University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-674-01147-2.

- ^ "Prime Focus".

- ^ Geoff Andersen (2007). The Telescope: Its History, Technology, and Future. Princeton University Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-691-12979-2.

- ^ a b "The Coude Focus".

- ^ a b "HARPS Instrument Description".

- ^ "ESPRESSO Instrument Description".

- ^ "Subaru PFS Instrumentation".