Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ashlar

View on Wikipedia

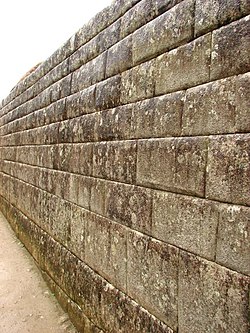

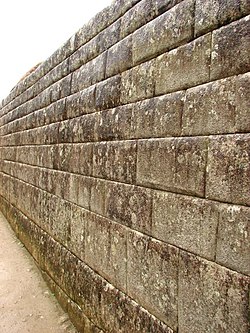

Ashlar (/ˈæʃlər/) is a term used to describe cut and dressed stone worked to achieve a specific form, typically rectangular; a structure built from such stones;[1] and the look created by the dressing technique. Ashlar stone may be dry laid or bedded in mortar.

Description

[edit]An ashlar block is the finest stone masonry unit, and is generally rectangular . It was described by Vitruvius as opus isodomum or trapezoidal. Precisely cut "on all faces adjacent to those of other stones", ashlar masonry is capable of requiring only very thin joints between blocks, and the exposed face of the stone may be smoothly polished, quarry-faced, rusticated, or tooled for decorative effect;[2][3] an example of the latter is "mason's drag", where a metal comb is used to cut small grooves, usually on softer stones.[4]

Ashlar masonry is in contrast to rubble masonry, which employs irregularly shaped stones, such as flat ledge or rounded river or lake stones, sometimes minimally worked or selected for similar size, or both. Ashlar masonry is related but generally distinct[clarify] from other stone masonry that is finely dressed but not quadrilateral, such as curvilinear and polygonal masonry.[3][5]

Ashlar masonry may be coursed, with stone blocks laid in continuous horizontal layers. Ashlar may also be random, which involves stone blocks laid with deliberately discontinuous courses, interrupted both vertically and horizontally, as in snecked masonry. In either case it is generally joined with a bonding material such as mortar, although dry laid ashlar construction is found, and metal ties and other methods of assembly have been used. The dry ashlar of Inca architecture in Cusco and Machu Picchu is particularly fine and famous.

Etymology

[edit]The word is attested in Middle English and derives from the Old French aisselier, from the Latin axilla, a diminutive of axis, meaning "plank".[6] "Clene hewen ashler" often occurs in medieval documents; this means tooled or finely worked, in contradistinction to rough-axed faces.[7]

In tile carpet installation "ashlar" refers to a vertical 1/2 offset pattern.[8]

Use

[edit]Ashlar blocks have been used in the construction of many buildings as an alternative to brick or other materials.[9]

In classical architecture, ashlar wall surfaces were often contrasted with rustication, each employing different chisels and techniques.

The term is frequently used to describe the dressed stone work of prehistoric Greece and Crete, although the dressed blocks are usually much larger than modern ashlar. For example, the tholos tombs of Bronze Age Mycenae use ashlar masonry in the construction of the so-called "beehive" dome. This dome consists of finely cut ashlar blocks that decrease in size and terminate in a central capstone.[10] These domes are not true domes, but are constructed using the corbel arch.

Ashlar masonry was also heavily used in the construction of palace facades on Crete, including Knossos and Phaistos. These constructions date to the MM III-LM Ib period, c. 1700–1450 BC.

In large scale modern European construction ashlar blocks are generally about 35 centimetres (14 in) in height.[citation needed] When shorter than 30 centimetres (12 in), they are usually called small ashlar.[citation needed]

As metaphor

[edit]In some Masonic groupings, which such societies term jurisdictions, ashlars are used as a symbolic metaphor for how one's personal development relates to the tenets of their lodge. As described in the explanation of the First Degree Tracing Board, in Emulation and other Masonic rituals the rough ashlar is a stone as taken directly from the quarry, and allegorically represents the Freemason prior to his initiation; a smooth ashlar (or "perfect ashlar") is a stone that has been smoothed and dressed by the experienced stonemason, and allegorically represents the Freemason who, through education and diligence, has learned the lessons of Freemasonry and who lives an upstanding life.[11]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Reich, Ronny; Katzenstein, Hannah (1992). "Glossary of Archaeological Terms". In Kempinski, Aharon; Reich, Ronny (eds.). The Architecture of Ancient Israel. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society. p. 312. ISBN 978-965-221-013-5.

- ^ Ching, Francis D. K.; Jarzombek, Mark M.; Prakash, Vikramaditya (2007). A Global History of Architecture. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. p. 759. ISBN 978-0-471-26892-5.

- ^ a b Sharon, Ilan (August 1987). "Phoenician and Greek Ashlar Construction Techniques at Tel Dor, Israel". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (267). Boston: The American Schools of Oriental Research: 32–33.

- ^ "The Conservation Glossary". University of Dundee. Archived from the original on 2010-05-19. Retrieved 2009-05-04.

- ^ Wright, George R. H. (2000). Ancient Building Technology, Vol 1: Historical Background. Technology and Change in History. Leiden, The Netherlands: E. J. Brill. p. 100. ISBN 978-90-04-09969-2. OCLC 490715142.

- ^ "Definition of ashlar". Oxford Dictionaries. Archived from the original on August 20, 2017.

- ^ One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Ashlar". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 733. This also attests the alternative spellings ashler and ashelere.

- ^ "Carpet Tile Installation Method". warehousecarpets.net. 3 April 2018. Retrieved 2024-10-22.

- ^ "Ashlar Masonry and its Types". The Constructor. 2018-12-17. Retrieved 2023-05-25.

- ^ Preziosi, D.; Hitchcock, L. A. (1999). Aegean Art and Architecture. Oxford History of Art. pp. 175–6. ISBN 0-19-284208-0.

- ^ "Rough and Perfect Ashlar". Masonic Lodge of Education. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

External links

[edit]Ashlar

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Characteristics

Physical Properties

Ashlar masonry is constructed using dimension stones selected for their mechanical and durability properties, which vary by material type such as limestone, sandstone, and granite. These properties are standardized by ASTM International and ensure the stones' suitability for load-bearing and exposed applications. Key properties include compressive strength, density, and water absorption, as outlined below for common types (ranges based on ASTM classifications; specific values depend on the stone variety and quarrying).[4]| Stone Type | Compressive Strength (psi) | Density (lb/ft³) | Water Absorption (% by weight) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Limestone (ASTM C568) | 1,800–35,000 | 110–185 | 0.2–29.0 |

| Sandstone (ASTM C616) | 2,000–37,000 | 125–170 | 1.0–20.0 |

| Granite (ASTM C615) | 4,700–60,000 | 150–200 | 0.02–0.70 |

Terminology and Etymology

The term "ashlar" originates from Middle English "assheler," borrowed from Old French "aisselier" or "aiseler," denoting a wooden beam or plank, which evolved to describe squared or dressed stone blocks due to their rectangular shape resembling timber supports. This Old French term derives from Medieval Latin "axillaris" or "ascellāris," a diminutive form related to "axis" (axle or board), ultimately tracing back to Latin roots emphasizing alignment and squaring, as in shaping stone with tools like axes.[5][6][7] In architectural terminology, several specialized terms describe elements of ashlar masonry. An "ashlar line" refers to a horizontal course or bedding line at the exterior face of a masonry wall, marking the level alignment of dressed stones for precise jointing. "Quoins" are the dressed ashlar blocks used at building corners, often larger or rusticated to provide structural reinforcement and visual emphasis. "Voussoirs" are wedge-shaped ashlar stones forming the curved portions of arches or vaults, with their tapered design distributing loads evenly to the keystone.[8][9][10] Regional variations in usage distinguish British and American contexts, with British terminology retaining a focus on traditional "ashlar" for finely dressed, rectangular masonry blocks in historical architecture, while American usage often equates it with "dimension stone" to emphasize standardized, quarried blocks cut to specific sizes for modern construction. In contemporary standards, "dimension stone" serves as a synonym encompassing ashlar, defined by the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) as natural stone blocks or slabs meeting precise dimensional and quality criteria for building applications. This standard formalizes ashlar-related requirements for absorption, density, and finishing to ensure uniformity in engineering contexts.[11]Historical Development

Ancient Origins

Early examples of dressed stone masonry appear in Neolithic sites in the ancient Near East, notably Göbekli Tepe in southeastern Turkey, dating to approximately 9600 BCE. Here, large T-shaped limestone pillars, some weighing up to 10 tons, were quarried from nearby bedrock and sculpted using basic stone tools, forming circular enclosures that represent some of the world's oldest monumental architecture. These elements demonstrate an early mastery of stone dressing for structural and symbolic purposes in ritual complexes.[12] In ancient Egypt, ashlar masonry advanced during the Old Kingdom around 2600 BCE, most prominently in the construction of the Giza pyramids, where millions of limestone blocks, typically weighing 2-3 tons, were cut and dressed from local quarries to create tight-fitting cores and smooth outer casings. These blocks were shaped with copper chisels and abrasives to achieve uniform faces and edges, often using gypsum mortar for stability and contributing to the pyramids' enduring load-bearing capacity for royal tombs. This technique marked a shift from earlier mudbrick and rubble construction, enabling the monumental scale of temple and funerary architecture that symbolized pharaonic power and eternity.[13] Mesopotamian civilizations incorporated dressed stones into ziggurats and palaces for enhanced stability, particularly in foundations and lower courses where mudbrick cores were vulnerable to flooding. Stone was used sparingly, mainly in bases of structures like those at Ur, providing a durable platform for religious rituals and administrative functions.[14] Greek and Roman innovations further refined ashlar techniques, with the Parthenon in Athens (completed 447 BCE) showcasing Pentelic marble blocks cut with high precision for dry-jointed walls and columns, emphasizing optical refinements in temple design. The Colosseum in Rome (70 CE) utilized travertine ashlar in its exterior arcades, with blocks precisely fitted without mortar to withstand immense loads in amphitheaters for public spectacles. These developments were facilitated by Bronze and Iron Age metal tools, such as chisels and saws, which allowed for the accurate dressing of hard stones, transforming ashlar into a cornerstone of classical monumental architecture for temples, tombs, and civic structures across the Mediterranean.[15][16]Medieval and Renaissance Evolution

During the Middle Ages, ashlar masonry became prominent in Romanesque and Gothic architecture, particularly in cathedrals and castles across Europe. In Gothic structures like Notre-Dame de Paris (construction began 1163) and Canterbury Cathedral (12th century), finely cut limestone blocks formed ribbed vaults, flying buttresses, and ornate facades, enabling taller, lighter designs with precise joints for structural integrity and aesthetic detail.[17] The Renaissance revived classical ashlar techniques in Italy and France, emphasizing symmetry and proportion. Architects like Filippo Brunelleschi used ashlar in the Florence Cathedral dome (completed 1436), while châteaux such as Chambord (begun 1519) featured dressed stone for grand facades and staircases, blending medieval solidity with antique elegance. This period saw ashlar's role in conveying humanism and permanence in palazzi and public buildings.[18]Production Methods

Quarrying and Sourcing

The quarrying of stone for ashlar begins with the careful selection of bedrock sites characterized by geological uniformity, where the stone exhibits minimal natural variations to ensure blocks can be cut into precise, rectangular forms suitable for fine masonry. Preferred materials, such as limestone and sandstone, are chosen for their inherent physical properties like durability and workability, which allow for clean extraction without excessive fracturing. Quality criteria emphasize the absence of faults, joints, or inclusions that could compromise structural integrity, alongside a consistent grain structure that facilitates even cutting and polishing. Joint analysis techniques are employed to map fracture patterns, optimizing block extraction while minimizing waste. These selections are guided by geological appraisals that prioritize deposits with low porosity and high compressive strength to meet the demands of ashlar's load-bearing applications.[19][20] Historically, quarrying for ashlar relied on manual labor in antiquity, where workers used wedging techniques—driving wooden or metal wedges into natural fissures or pre-cut channels—to split stone along predetermined lines, a method effective for softer stones like limestone and sandstone. This labor-intensive process, dating back to Neolithic times around 4000 BC in regions like Britain, involved hand tools such as chisels and hammers to exploit natural bedding planes. By the 17th century, the introduction of gunpowder blasting marked a significant advancement, allowing for the controlled fragmentation of larger volumes of rock; quarrymen drilled holes, filled them with powder, and ignited charges to create fissures, revolutionizing extraction efficiency in Europe. This shift from purely manual methods to explosive techniques enabled the sourcing of bigger blocks for monumental architecture.[21][22][23] During the Industrial Revolution, quarrying evolved further with steam-powered machinery, including drills and cranes, which mechanized the wedging and lifting processes, dramatically increasing output and reducing reliance on manual effort. In the 19th century, steam engines facilitated deeper excavations and faster transport of blocks from sites like Portland's oolitic limestone quarries in England, operational since Roman times but scaled up for imperial projects. Modern practices have adopted diamond wire saws, introduced in the late 20th century, which use embedded diamond beads on a tensioned wire to slice through hard stone with precision, minimizing overbreak and dust compared to blasting. This method, prevalent in marble quarries since the 1980s, allows for the extraction of large, fault-free slabs up to several meters in dimension.[22][24][25] Sourcing decisions for ashlar stone prioritize proximity to construction sites to reduce transportation costs and logistical challenges, as heavy blocks can account for a significant portion of project expenses. Iconic examples include the Portland stone quarries on England's Isle of Portland, which supplied fine-grained limestone for landmarks like St. Paul's Cathedral due to their relatively close access to London via sea routes. Similarly, the Carrara marble quarries in Italy's Apuan Alps have been a primary source since ancient Roman times, providing high-purity white marble valued for its uniformity and transported globally despite the distance. These sites are selected not only for quality but also for established infrastructure that supports efficient supply chains.[26][27][28] Contemporary quarrying practices address environmental impacts through measures like dust suppression systems, including water sprays and enclosed cutting operations, to mitigate airborne particulates that can affect air quality and nearby ecosystems. Habitat disruption from excavation is minimized via site rehabilitation plans, such as revegetation and erosion control, though challenges persist in sensitive areas where quarrying alters landscapes and biodiversity. In regions like the Apuan Alps, regulations enforce progressive restoration to offset habitat loss, ensuring long-term sustainability in ashlar stone production.[29][30][31]Dressing and Finishing Techniques

Dressing ashlar involves a series of post-quarrying processes that transform irregular, rough-cut stone blocks into precisely shaped and surfaced units suitable for masonry. These stages typically occur at or near the quarry to minimize transportation costs of oversized material. The primary goal is to achieve uniform dimensions, flat beds and joints, and desired surface qualities while preserving the stone's structural integrity.[32] The process commences with rough squaring, where heavy picks, hammers, and chisels remove protrusions and approximate the block's form to the required size. This initial sizing addresses the stone's natural variations, reducing bulk before finer work. Subsequent fine tooling refines the faces, joints, and edges using specialized implements like point chisels for roughing and drafting chisels for straight lines, resulting in smooth, planar surfaces essential for load-bearing applications. For textured effects, bush-hammering employs a multi-pointed hammer to pit and roughen the face uniformly, creating a non-slip or decorative stipple without altering the block's overall shape.[32][33][34] Tools for ashlar dressing have evolved from rudimentary implements to advanced machinery, reflecting advancements in efficiency and precision across eras. In ancient periods, such as the Bronze Age Eastern Mediterranean, basic stone and metal chisels, along with adze-like tools, were used to shape and surface blocks manually. Medieval craftsmen refined these with claw chisels—serrated-edged tools struck by mallets—to produce even textures on ashlar faces. The 19th century introduced pneumatic drills, powered by compressed air, which accelerated chipping and drilling on hard stones like granite, marking a shift from labor-intensive handwork. Contemporary production relies on computer numerical control (CNC) machining centers, which automate cutting paths for complex profiles and tolerances as fine as 0.02 mm, enabling scalable output for modern projects.[35][36][37][38] Finishing techniques determine the ashlar's aesthetic and functional properties, with common variants including plain (smooth), rock-faced (textured), and polished surfaces. Plain finishes are attained through progressive planing and rubbing with finer chisels or abrasives, yielding a uniform, low-relief face ideal for clean lines. Rock-faced dressing pitches a rough, quarry-split texture within tooled margins using bush hammers or pitching tools, balancing natural appearance with structural alignment. Polished finishes, applied to softer stones like limestone or marble, involve sequential abrasive grinding and buffing to achieve a reflective sheen. Regardless of finish, edges are meticulously dressed to form precise joints, typically accommodating thin mortar lines of about 1/8 inch (3 mm) for seamless bonding and minimal visible bedding.[39][36][32][40] Precision throughout dressing is paramount for safety and efficiency, with masons relying on squares, levels, and straightedges to verify perpendicularity and flatness at each stage, preventing misalignment in assembly. Reusable templates—often cut from durable materials like PVC or wood—guide repetitive shaping tasks, ensuring dimensional consistency across batches and reducing stone waste by optimizing cuts from larger slabs. These practices not only enhance accuracy but also mitigate risks associated with manual handling of heavy tools and blocks.[41][42]Types and Variations

By Surface Finish

Ashlar masonry is categorized by surface finish to distinguish variations in texture, tooling, and joint treatment, which influence both aesthetic appeal and structural perception in architectural contexts. These finishes are achieved through specific dressing techniques, such as polishing or chiseling, to create distinct visual effects while maintaining the uniform block dimensions characteristic of ashlar.[2] Smooth ashlar features finely dressed stone blocks with polished or lightly tooled surfaces, allowing for seamless, thin mortar joints that emphasize uniformity and elegance. This finish is prevalent in classical facades, where the flat faces create a refined, wall-like appearance without visible texture disruptions.[2] Rusticated ashlar, in contrast, employs rough-hewn or textured block faces combined with deep, often V-shaped joints that project a sense of ruggedness and emphasize the stone's natural qualities. A notable example is the Palazzo Rucellai in Florence, constructed in the 1460s under Leon Battista Alberti's design, where smooth-faced rustication with deep-set bordering bands forms a geometric lattice, blending Renaissance proportions with classical influences for enhanced visual depth.[43] This technique, evolving from earlier Florentine palaces, highlights the material's solidity while introducing shadow play through joint relief.[43] Tooled ashlar involves chiseling the block faces to create textured surfaces, providing a controlled irregularity that adds tactile interest. Such finishes are achieved by systematic tool marks.[44] Smooth ashlar offers an elegant, monolithic aesthetic ideal for refined elevations but demands intensive labor for precise dressing, increasing construction costs. Rusticated ashlar, by retaining more natural texture, reduces finishing time. Tooled ashlar balances these by adding decorative depth without full polishing, though it requires skilled masonry to ensure pattern consistency.[44]By Material Composition

Ashlar masonry can be constructed from various stone types, each offering distinct properties that influence durability, workability, and aesthetic qualities. Common materials include limestone, sandstone, granite, and marble. Limestone, a soft sedimentary stone, is easily carved, making it suitable for intricate detailing in historical structures such as Gothic cathedrals. It provides a light color and smooth finish but may require protection from weathering.[1] Sandstone is known for its durability and range of colors, often used in both ancient and modern architecture for its resistance to erosion while allowing for fine dressing.[1] Granite, a hard igneous rock, is valued for its strength and longevity, commonly employed in load-bearing elements and contemporary facades where high compressive strength is required.[3] Marble is used primarily for decorative purposes due to its translucency and ability to take a high polish, featured in classical buildings for columns and veneers.[1] The choice of material depends on local availability, intended use, and environmental conditions.Architectural and Structural Uses

In Load-Bearing Structures

Ashlar masonry plays a crucial role in load-bearing structures by providing robust support through precisely cut and fitted stone blocks that distribute vertical loads effectively. The interlocking nature of these blocks, achieved via tight joints, ensures gravity-based stability, allowing the structure to resist compressive forces primarily through the stone's inherent strength rather than extensive mortar bonding. In traditional applications, minimal mortar—often lime-based—is used, enabling the assembly to handle high compressive loads; for instance, granite ashlar can achieve compressive strengths exceeding 19,000 psi, far surpassing typical building requirements.[45] This structural approach is evident in various load-bearing elements, including walls, columns, and arches, where ashlar's uniform dimensions facilitate even load transfer to the foundation. Iconic examples include the massive ashlar blocks in the arches of the Roman aqueduct at Pont du Gard, which span valleys while supporting immense water weights without collapse over centuries.[46] Similarly, ancient Egyptian temple walls, such as those at Karnak, employed large ashlar limestone blocks to bear the load of towering pylons and roofs, demonstrating the material's reliability in monumental construction.[47] Variations in material composition, like limestone versus granite, influence overall strength, with denser granites offering higher load capacities in such applications. Ashlar's advantages in load-bearing roles stem from its material properties, including substantial thermal mass that moderates indoor temperatures by absorbing and releasing heat slowly, thereby enhancing energy efficiency in buildings. Additionally, its non-combustible nature provides superior fire resistance, with stone masonry capable of withstanding high temperatures for extended periods without structural degradation, often exceeding two-hour fire ratings in modern tests.[48][49] However, challenges arise in seismic zones, where rigid ashlar assemblies are susceptible to differential settling—uneven foundation movement that can induce cracking or failure under earthquake-induced lateral forces—necessitating careful site preparation and flexible jointing.[50] In contemporary engineering, ashlar is integrated into hybrid systems with steel reinforcement to mitigate these vulnerabilities, combining stone's compressive prowess with steel's tensile strength for enhanced ductility. Such hybrid masonry-steel frames, analyzed as integrated systems, allow for taller load-bearing walls while improving seismic performance through embedded rebar or post-tensioning, as seen in retrofitted historic structures and new sustainable designs.[51][52]In Decorative and Ornamental Applications

Ashlar masonry is widely employed in decorative and ornamental contexts where its smooth, uniform appearance enhances architectural aesthetics without primary structural demands. Often used as a veneer over rubble, brick, or concrete cores, ashlar provides a refined facade with thin joints, typically under 0.5 inches, creating an illusion of solid stone construction while reducing material costs and weight.[1][3] In ornamental applications, ashlar blocks can be carved or tooled for added texture and detail, such as beveled edges or subtle chisel patterns, contributing to visual interest in non-load-bearing elements like interior walls, entryways, and garden features. Common in civic buildings, residences, and monuments, examples include the polished limestone ashlar cladding on classical revival structures and modern veneers in sustainable designs that prioritize durability and low maintenance. Its weather-resistant qualities make it ideal for exterior ornamentation, offering long-term elegance with minimal upkeep.[2]Symbolic and Cultural Significance

Metaphorical Interpretations

In religious contexts, ashlar has served as a metaphor for foundational truths and spiritual refinement, particularly through the imagery of the cornerstone. Psalm 118:22 describes "the stone which the builders refused" becoming "the head stone of the corner," symbolizing a rejected element that forms the essential basis of a structure, often interpreted as a divine foundation or messianic figure central to salvation. This architectural motif underscores ashlar's precision and durability as emblems of enduring truth amid rejection.[53] Within Freemasonry, the "perfect ashlar"—a smoothly dressed, cubical stone—represents the moral and spiritual perfection achieved through personal discipline and enlightenment, contrasting with the "rough ashlar" of the unrefined individual.[54] This symbolism draws from operative masonry's emphasis on transforming raw material into ordered form, illustrating the Mason's journey toward ethical completeness and harmony with universal principles.[55] The perfect ashlar thus embodies the ideal of self-improvement, where precision in craftsmanship mirrors the cultivation of virtue.[56] Ashlar's qualities of exactitude and seamless integration have inspired broader metaphorical interpretations of order emerging from chaos. In philosophical and literary traditions up to the 19th century, the stone's finely worked surfaces and invisible joints evoke civilized structure imposed on natural disorder, with the mortarless bonds symbolizing unity amid diversity—distinct elements cohering into a stable whole.[57] This reflects how ashlar's refined smoothness, derived from its dressed physical properties, signifies societal or intellectual refinement over primal irregularity.[58]Modern Symbolic References

In the 20th century and continuing into the present, ashlar symbolism has been central to Freemasonry, where the rough ashlar and perfect ashlar serve as enduring metaphors for human moral and spiritual refinement. The rough ashlar, depicted as an unhewn stone taken directly from the quarry, represents the initiate's initial state of imperfection and untapped potential, while the perfect ashlar symbolizes the achieved ideal of a balanced, enlightened individual shaped by ethical education, self-discipline, and fraternal guidance. This duality underscores Freemasonry's emphasis on personal transformation, with the tools of the craft—such as the chisel and mallet—illustrating the ongoing process of improvement. These symbols appear in Masonic rituals, lodge decorations, and educational materials worldwide, maintaining their relevance in a secular age as emblems of character building.[59][60] In popular media and digital culture as of 2025, ashlar-inspired elements occasionally appear as motifs for foundational integrity, though less explicitly symbolic than in Masonic traditions. Video games like Minecraft feature block-based stone crafting that parallels ashlar assembly, interpreted by some as a metaphor for building stable worlds from raw materials, echoing themes of creation and order in player-driven narratives. These adaptations reflect an evolving symbolism from physical solidity to abstract reliability in virtual realms.[61]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/ashlar