Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cytosis

View on Wikipedia

Cytosis (as the biological suffix ‑cytosis) is used in words that describe either the quantity or condition of cells (e.g., leukocytosis, erythrocytosis) or processes that move material across cellular membranes. The three cellular transport processes are endocytosis (into the cell), exocytosis (out of the cell) and transcytosis (through the cell). Related endings include -osis (as in necrosis, apoptosis) and -esis (e.g., diapedesis, emperipolesis, cytokinesis).

Etymology and pronunciation

[edit]The suffix -cytosis (/saɪˈtoʊsɪs/) uses combining forms of cyto- and -osis, reflecting a cellular process. The term was coined by Novikoff in 1961.[1]

Processes related to subcellular entry or exit

[edit]Endocytosis

[edit]Endocytosis is when a cell absorbs a molecule, such as a protein, from outside the cell by engulfing it with the cell membrane. It is used by most cells, because many critical substances are large polar molecules that cannot pass through the cell membrane. The two major types of endocytosis are pinocytosis and phagocytosis.

Pinocytosis

[edit]- Pinocytosis, also known as cell drinking, is the absorption of small aqueous particles along with the membrane receptors that recognize them. It is an example of fluid phase endocytosis and is usually a continuous process within the cell. The particles are absorbed through the use of clathrin-coated pits. These clathrin-coated pits are short lived and serve only to form a vesicle for transfer of particles to the lysosome. The clathrin-coated pit invaginates into the cytosol and forms a clathrin-coated vesicle. The clathrin proteins will then dissociate.[2] What is left is known as an early endosome. The early endosome merges with a late endosome. This is the vesicle that allows the particles that were endocytosed to be transported into the lysosome. Here there are hydrolytic enzymes that will degrade the contents of the late endosome. Sometimes, rather than being degraded, the receptors that were endocytosed along with the ligand are then returned to the plasma membrane to continue the process of endocytosis.

- Receptor-mediated endocytosis

- Receptor-mediated endocytosis is a mode of pinocytosis. Proteins in the clathrin coat on the plasma membrane have propensity to bind and trap macromolecules or ligands. However, it is not the receptors in the pit that caused the pinocytosis. The vesicles would have formed regardless of whether or not the receptors and ligand were there.[3] This is why it is still a continuous non-triggered event, unlike phagocytosis, which is explained below.

Phagocytosis

[edit]- Phagocytosis, also known as cell eating, is the absorption of larger particles such as bacteria into the cytosol. In smaller single-celled organisms, this is how it feeds. In larger multicellular organisms, it is a way of destroying old or damaged cells or ingesting microbial invaders. In the case of ingesting a bacterium, the bacterium will be bound by antibodies in the aqueous environment. When this antibody runs into a receptor on the surface of a cell, the plasma membrane responds by extending itself to surround the bacterium. Thus, phagocytosis is not a randomly occurring event. It is triggered by a ligand binding to a receptor.

Some cells are specially designed to phagocytize. These cells include Natural Killer cells, macrophages, and neutrophils. All of these are involved in the immune response and serve to degrade foreign or antigenic material[4]

Exocytosis

[edit]

Exocytosis is when a cell directs the contents of secretory vesicles out of the cell membrane. The vesicles fuse with the cell membrane and their content, usually protein, is released out of the cell. There are two types of exocytosis: Constitutive secretion and Regulated secretion. In both of these types, a vesicle buds from the Golgi Apparatus and is shuttled to the plasma membrane, to be exocytosed from cell. Exocytosis of lysosomes commonly serves to repair damaged areas of the plasma membrane by replenishing the lipid bilayer.[5]

- Constitutive secretion (irregulated exocytosis)

- This is when the vesicle that buds from the Golgi Apparatus contains both soluble proteins as well as lipids and proteins that will remain on the plasma membrane after fusion of the vesicle. This type of secretion is unregulated. The vesicle will eventually travel to the plasma membrane and fuse with it. The contents of the cell will be released into the extra-cellular space while the components of the vesicle membrane (plasma membrane lipids and proteins) will establish themselves as part of the cell's plasma membrane.

- Regulated secretion (regulated exocytosis)

- This is when the cell receives a signal from the extra-cellular space, such as a neurotransmitter or hormone, that regulates the fusing of the vesicle to the plasma membrane and the release of its contents. The vesicle is transported to the plasma membrane. There it sits until it receives a signal to fuse with the membrane and release its contents into the extra-cellular space.[4]

Transcytosis

[edit]Transcytosis is a type of cytosis that allows particles to be shuttled from one membrane to another. An example of this would be when a receptor normally lies on the basal or lateral membrane of an epithelial cell, but needs to be trafficked to the apical side. This can only be done through transcytosis due to tight junctions, which prevent movement from one plasma membrane domain to another. This type of cytosis occurs commonly in epithelium, intestinal cells, and blood capillaries. Transcytosis can also be taken advantage of by pathogenic molecules and organisms. Several studies have shown that bacterium can easily enter intestinal lumen through transcytosis of goblet cells.[6] Other studies, however, are exploring the idea that transcytosis may play a role in allowing medications to cross the blood-brain barrier. Exploiting this fact may allow certain drug therapies to be better utilized by the brain.[7]

Methods of cytosis not only move substances in, out of, and through cells, but also add and subtract membrane from the cell's plasma membrane. The surface area of the membrane is determined[citation needed] by the balance of the two mechanisms and contributes to the homeostatic environment of the cell.

Phenomenon related to cellular transformation or movements

[edit]Diapedesis

[edit]Movement of blood cells across endothelial layer

Emperipolesis

[edit]entering one cell into another

Trogocytosis

[edit]Double membrane endocytosis of one cells part by another

Efferocytosis

[edit]Phagocytosis of apoptotic cells.

Cytokinesis

[edit]Last part of cell division when two daughter cells separate

Phenonomena related to cellular predominance

[edit]Leukocytosis

[edit]increase in number of leukocytes.

Thrombocytosis

[edit]increase in platelet or thrombocytes

Erythrocytosis

[edit]increase in RBC, usually a part of polycythemia where RBC total mass is increased.

Phenomenon related to cellular morphology

[edit]Microcytosis

[edit]Small diameter or volume of cells eg RBC when classifying anemia which means microcytes dominating the blood picture.

Macrocytosis

[edit]Larger cells (macrocytes) dominating cellular population (RBCs).

Anisocytosis

[edit]Heterogeneity of size of cells.

Spherocytosis

[edit]Spherical cells (spherocytes) dominating cellular population (RBCs).

Ovalocytosis

[edit]Predominance of oval shaped cells.

Drepanocytosis

[edit]Sickled cells dominating blood picture.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Rieger, R.; Michaelis, A.; Green, M.M. (2012). Glossary of Genetics: Classical and Molecular. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. ISBN 978-3-642-75333-6.[page needed]

- ^ Rappoport, Joshua Z. (2008-06-15). "Focusing on clathrin-mediated endocytosis". Biochemical Journal. 412 (3): 415–423. doi:10.1042/BJ20080474. ISSN 0264-6021. PMID 18498251.

- ^ Mukherjee, S.; Ghosh, R. N.; Maxfield, F. R. (1997-07-01). "Endocytosis". Physiological Reviews. 77 (3). American Physiological Society: 759–803. doi:10.1152/physrev.1997.77.3.759. ISSN 0031-9333. PMID 9234965.

- ^ a b Lodish, Harvey; Berk, Arnold; Kaiser, Chris A.; Krieger, Monty; Bretscher, Anthony; Ploegh, Hidde; Amon, Angelika; Scott, Matthew P. (2012-05-02). Molecular Cell Biology (7th ed.). W. H. Freeman. ISBN 978-1-4292-3413-9.[page needed]

- ^ Xu, Jin; Toops, Kimberly A.; Diaz, Fernando; Carvajal-Gonzalez, Jose Maria; Gravotta, Diego; Mazzoni, Francesca; et al. (2012-12-15). "Mechanism of polarized lysosome exocytosis in epithelial cells". Journal of Cell Science. 125 (24). The Company of Biologists: 5937–5943. doi:10.1242/jcs.109421. ISSN 1477-9137. PMC 3585513. PMID 23038769.

- ^ Nikitas, Georgios; Deschamps, Chantal; Disson, Olivier; Niault, Théodora; Cossart, Pascale; Lecuit, Marc (2011-10-24). "Transcytosis of Listeria monocytogenes across the intestinal barrier upon specific targeting of goblet cell accessible E-cadherin" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Medicine. 208 (11): 2263–2277. doi:10.1084/jem.20110560. ISSN 1540-9538. PMC 3201198. PMID 21967767.

- ^ Yu, Y. Joy; Zhang, Yin; Kenrick, Margaret; Hoyte, Kwame; Luk, Wilman; Lu, Yanmei; Atwal, Jasvinder; Elliott, J. Michael; Prabhu, Saileta; Watts, Ryan J.; Dennis, Mark S. (2011-05-25). "Boosting Brain Uptake of a Therapeutic Antibody by Reducing Its Affinity for a Transcytosis Target". Science Translational Medicine. 3 (84): 84ra44. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3002230. ISSN 1946-6234. PMID 21613623.

Cytosis

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

The suffix -cytosis in biological and medical terminology is derived from the Greek kytos, meaning "hollow vessel" or "cell," combined with -osis, which denotes a process, condition, or abnormal increase.[4] This suffix broadly indicates either the active movement or transport of cellular materials across membranes or an abnormal proliferation or state of cells.[2] For instance, in processes like endocytosis, it refers to the cellular uptake of substances, while in conditions like leukocytosis, it signifies an elevated count of white blood cells.[5][6] A key distinction exists between process-oriented cytoses, which describe dynamic mechanisms of cellular transport and interaction, and condition-oriented cytoses, which denote pathological or quantitative alterations in cell populations. Process-oriented examples include vesicular transport phenomena, where cells engulf or release materials via membrane-bound vesicles, and cellular interactions involving migration or engulfment between cells.[3] In contrast, condition-oriented cytoses often highlight abnormalities, such as quantitative increases (e.g., erythrocytosis for excess red blood cells) or morphological variants (e.g., anisocytosis for unequal cell sizes).[2] This duality underscores the suffix's versatility in encapsulating both functional and dysfunctional cellular behaviors. The term's usage originated in the 19th century, initially applied to cell-related pathological conditions; for example, "leukocytosis" was first documented in medical literature in 1866 to describe elevated leukocytes.[6] Its application expanded in the mid-20th century to encompass transport processes, with terms like "endocytosis" coined in 1963 to denote intracellular material acquisition.[7] These broad categories—vesicular transport, cellular interactions, quantitative abnormalities, and morphological variants—illustrate how -cytosis has evolved to frame diverse aspects of cellular physiology and pathology without implying specific mechanisms.[8]Etymology and Pronunciation

The term "cytosis" derives from the combining form "cyto-," originating from the Ancient Greek κύτος (kútos), meaning "hollow vessel," "container," or "cell," which entered scientific English in the mid-19th century to denote cellular structures.[9] The suffix "-osis" comes from Ancient Greek -ωσις (-ōsis), typically indicating a process, action, state, condition, or abnormal increase, as seen in various medical and pathological terms. Together, these elements form "-cytosis" as a suffix specifically denoting cellular processes or conditions involving movement, uptake, or proliferation.[1] The term "cytosis" as a general descriptor for subcellular vesicular transport processes was introduced by cell biologist Albert B. Novikoff in his 1961 research on lysosomes and cellular ingestion mechanisms, extending earlier pathological uses of "-cytosis" for cellular abnormalities.[10] This coinage built on precedents like "pinocytosis" (coined in 1931) to encompass related membrane-bound activities in eukaryotic cells. In phonetic transcription, "cytosis" is pronounced /saɪˈtoʊsɪs/ in General American English, approximated as "sigh-TOH-sis," emphasizing the long "o" sound in the second syllable.[11] In British English, it varies slightly to /saɪˈtəʊsɪs/, with a shorter, more central vowel in the stressed syllable, often rendered as "sigh-TOH-sis" or "sigh-TAW-sis."[12] The suffix "-cytosis" differs from related forms like "-esis," derived from Ancient Greek -ήσις (-ḗsis), which denotes an action, process, or movement (e.g., diapedesis for cellular migration through tissues), whereas "-cytosis" more precisely applies to cellular contexts involving conditions, increases, or dynamic vesicular events. For instance, in pathological terminology, "-cytosis" appears in terms like leukocytosis, denoting an abnormal increase in white blood cells.[2]Vesicular Transport Processes

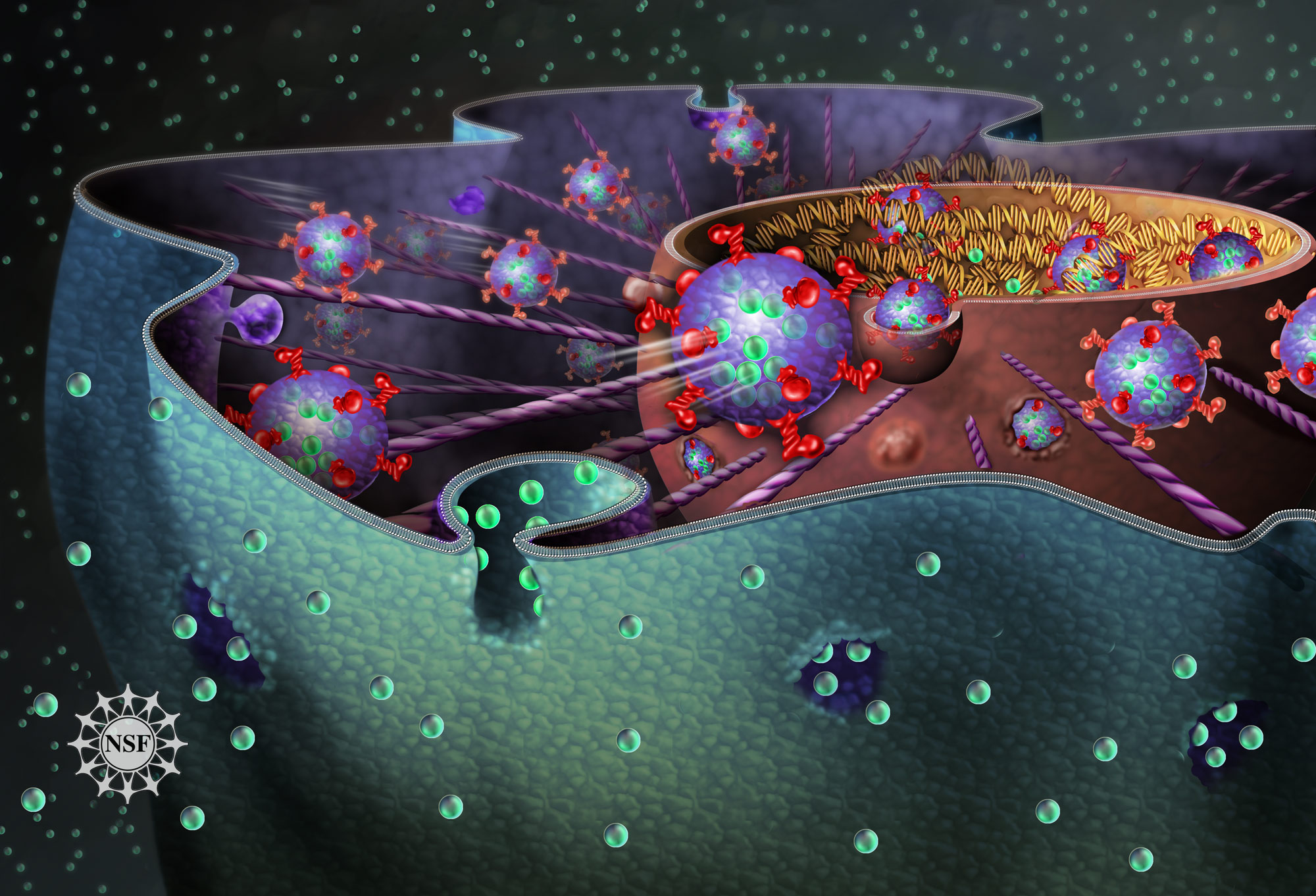

Endocytosis

Endocytosis is an active transport mechanism by which eukaryotic cells internalize extracellular materials, such as fluids, solutes, or particles, through invagination of the plasma membrane to form membrane-bound vesicles. This process is energy-dependent, primarily relying on ATP hydrolysis to drive membrane deformation, cargo selection, and vesicle scission.[13] It occurs ubiquitously across eukaryotic cells and is regulated by a variety of proteins that coordinate membrane curvature and cytoskeletal remodeling.[14] The mechanism begins with the plasma membrane engulfing the target material, often facilitated by coat proteins like clathrin that stabilize invaginations into pits. These pits deepen and pinch off to generate vesicles, typically 50–200 nm in diameter for small-scale uptake, which then traffic to intracellular compartments such as early endosomes for sorting.[13] The actin cytoskeleton plays a crucial role in providing mechanical force for membrane invagination, particularly through polymerization driven by complexes like Arp2/3, while dynamin, a GTPase, mediates the final scission of vesicles from the membrane by assembling into collars that constrict and sever the neck.[14] This energy-intensive process contrasts with passive diffusion and enables cells to control the uptake of specific molecules.[13] Endocytosis encompasses distinct subtypes tailored to the size and specificity of cargo. Pinocytosis, often termed "cell drinking," involves the non-specific ingestion of extracellular fluid and dissolved macromolecules into small vesicles (approximately 100 nm), occurring constitutively in most cells to sample the environment.[13] Phagocytosis, or "cell eating," is a specialized form for engulfing large particles greater than 0.5 μm, such as bacteria or apoptotic cells, predominantly in professional phagocytes like macrophages and neutrophils; it forms large phagosomes that fuse with lysosomes for enzymatic degradation.[13] Receptor-mediated endocytosis provides high specificity, where cell-surface receptors cluster in clathrin-coated pits to bind ligands like low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, leading to selective internalization and subsequent recycling or degradation of the cargo.[13][14] Biologically, endocytosis supports nutrient acquisition by importing essential molecules that cannot cross the membrane unaided, such as iron via transferrin receptors.[13] In immune defense, it enables pathogen clearance through phagocytosis and antigen presentation by processing engulfed material for MHC loading on dendritic cells.[14] Additionally, it regulates signaling by downregulating receptors, preventing overstimulation, and occurs in nearly all eukaryotic cells to maintain membrane homeostasis.[13] The term "endocytosis" was coined by Christian de Duve in 1963 during the Ciba Foundation Symposium on Lysosomes, unifying concepts of particle and fluid uptake previously described separately.[15] Seminal observations of the process date to the 1930s, with phagocytosis first noted by Élie Metchnikoff in 1883 for its role in immunity.[16]Exocytosis

Exocytosis is the active transport process by which eukaryotic cells expel macromolecules, such as proteins, hormones, and neurotransmitters, from intracellular vesicles into the extracellular environment through the fusion of vesicle membranes with the plasma membrane. This mechanism enables the targeted release of cellular contents while simultaneously incorporating vesicle membranes into the plasma membrane, contributing to its expansion and maintenance. Unlike passive diffusion, exocytosis requires energy from ATP hydrolysis and is tightly regulated to ensure precise control over secretion timing and location. The core mechanism of exocytosis involves secretory vesicles originating from the trans-Golgi network, where proteins synthesized in the endoplasmic reticulum are processed and packaged. These vesicles are transported along cytoskeletal tracks to the plasma membrane, where they undergo tethering and docking mediated by Rab GTPases, which recruit effector proteins to position vesicles correctly, and SNARE proteins, including syntaxin on the target membrane, which form complexes to drive bilayer fusion. In regulated exocytosis, this fusion is typically triggered by a rise in intracellular calcium ions (Ca²⁺), which bind to sensors like synaptotagmin to accelerate the process and open a fusion pore for content expulsion; constitutive exocytosis, by contrast, proceeds continuously without such triggers. Exocytosis manifests in two primary subtypes: constitutive secretion, a default, unregulated pathway present in all eukaryotic cells that continuously releases molecules like extracellular matrix proteins without external stimuli, ensuring steady-state maintenance of the extracellular milieu; and regulated secretion, which is stimulus-dependent and confined to specialized secretory cells, such as neurons releasing neurotransmitters upon action potentials or endocrine cells discharging hormones in response to signals. The SNARE-mediated fusion in regulated forms exemplifies this, as seen in synaptic vesicles where v-SNAREs on the vesicle interact with t-SNAREs like syntaxin and SNAP-25 on the plasma membrane to enable rapid, calcium-triggered discharge. Biologically, exocytosis is indispensable for hormone secretion from glands, such as insulin release from pancreatic beta cells, waste elimination through lysosomal exocytosis, and synaptic transmission where neurotransmitter vesicles fuse to propagate neural signals across synapses, thereby underpinning intercellular communication and physiological coordination. First observed in the 1950s through electron microscopy studies of adrenal chromaffin cells and synaptic terminals, which captured vesicle docking and fusion events, exocytosis has since been elucidated as a conserved process involving Rab GTPases for initial tethering and syntaxin for SNARE complex assembly. This pathway contrasts with endocytosis as its reciprocal process, together balancing membrane flux in cells.Transcytosis

Transcytosis is a vesicular transport process that enables the bidirectional movement of molecules, such as proteins and nutrients, across polarized epithelial or endothelial cells. It involves the sequential uptake of cargo via endocytosis from one plasma membrane domain, intracellular trafficking through vesicles, and release via exocytosis at the opposite domain. This mechanism allows selective passage of large substances that cannot diffuse paracellularly, maintaining barrier integrity while facilitating essential exchanges.[17][18] The process is exemplified by receptor-mediated transcytosis, where specific ligands bind surface receptors to initiate uptake. A prominent case is the transport of dimeric immunoglobulin A (IgA) across intestinal epithelial cells, mediated by the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor (pIgR). Basolaterally endocytosed IgA-pIgR complexes are trafficked to the apical surface, where proteolytic cleavage releases secretory IgA into the lumen for mucosal immunity.[19] The term "transcytosis" was coined in 1979 by Nicolae Simionescu to describe this vectorial macromolecular transport in capillary endothelium.[20] Transcytosis plays critical roles in physiological functions, including immune surveillance through antigen sampling by microfold (M) cells in gut-associated lymphoid tissue, where luminal particles are transcytosed to underlying immune cells for response initiation. It also holds promise for drug delivery, particularly across the blood-brain barrier (BBB), where receptor-mediated transcytosis (RMT) via transferrin or insulin receptors enables targeted transport of therapeutics into the central nervous system. Transcytosis occurs in subtypes distinguished by uptake specificity: fluid-phase transcytosis, a constitutive non-specific process capturing extracellular fluid, versus receptor-mediated transcytosis, which is ligand-directed and regulated. Endocytic pathways include clathrin-dependent mechanisms forming coated pits for efficient cargo sorting and caveolin-dependent caveolae for lipid raft-associated transport. This process is essential in polarized cells like endothelial barriers, where it regulates permeability.[21][22][23][24] In certain pathological conditions, transcytosis is modulated; for instance, during inflammation, myeloid-derived growth factor (MYDGF) secreted by inflammatory cells inhibits low-density lipoprotein (LDL) transcytosis across arterial endothelium, thereby attenuating atherosclerosis progression. Transcytosis builds on endocytosis and exocytosis by directing vesicular fusion to the opposing membrane domain in polarized cells.[25]Cellular Movement and Interaction Processes

Diapedesis

Diapedesis, also known as leukocyte transendothelial migration, is the process by which white blood cells, particularly leukocytes such as neutrophils and monocytes, actively migrate from the bloodstream across the endothelial barrier of blood vessels into surrounding tissues.[26] This directed movement is a critical step in the inflammatory response, allowing immune cells to reach sites of infection or injury without causing widespread vascular leakage.[27] Unlike passive diffusion, diapedesis is an energy-dependent, regulated process involving specific molecular interactions and cytoskeletal rearrangements that ensure precise and efficient extravasation.[26] The mechanism of diapedesis begins with leukocyte adhesion to the vascular endothelium, mediated by selectins and integrins. Initial tethering and rolling occur via E-selectin and P-selectin on endothelial cells binding to ligands like PSGL-1 on leukocytes, slowing their movement in the blood flow.[27] Firm adhesion follows through integrin activation, where LFA-1 (αLβ2) and Mac-1 (αMβ2) on leukocytes bind to ICAM-1 and ICAM-2 on endothelial cells, triggered by chemokine signaling such as that from IL-8 (CXCL8), which upregulates integrin affinity via inside-out signaling.[26][28] Following adhesion, leukocytes crawl along the endothelium to find suitable transmigration sites, guided by chemokine gradients and homophilic interactions. Transmigration can proceed via paracellular or transcellular routes: in the paracellular pathway, leukocytes squeeze through endothelial junctions involving PECAM-1 (CD31), JAM-A, and CD99, which transiently loosen adherens junctions like VE-cadherin through phosphorylation by kinases such as Src and MLCK.[27][26] In the transcellular route, leukocytes form invasive podosome-like protrusions that penetrate the endothelial cell body, creating a temporary channel while preserving junctional integrity, facilitated by actin polymerization driven by Rac2 and RhoA GTPases via PI3K/Akt pathways.[27] Actin remodeling is essential for generating the force needed to squeeze through the barrier, with endothelial cells actively contributing by recruiting the lateral border recycling compartment to supply membrane for the passage.[26] Biologically, diapedesis plays a pivotal role in the immune response to infection and inflammation, enabling rapid recruitment of leukocytes to affected tissues as part of the leukocyte extravasation cascade.[27] It is upregulated during inflammation by proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines like IL-8, which not only activate adhesion but also direct migration toward infection sites, enhancing host defense against pathogens.[28] Defects in diapedesis, such as those in leukocyte adhesion deficiency (LAD) syndromes caused by mutations in integrin subunits (e.g., ITGB2 in LAD-I) or activators like KINDLIN3 (in LAD-III), lead to recurrent infections due to impaired neutrophil extravasation and elevated circulating leukocyte counts.[26] The phenomenon of diapedesis was first observed in the 19th century by microscopists like Julius Cohnheim, who in 1867 described leukocytes emigrating from vessels during inflammation, laying the foundation for understanding immune cell trafficking.[29]Emperipolesis

Emperipolesis is the active penetration of one intact cell into the cytoplasm of another cell, where the internalized cell remains viable without undergoing lysosomal degradation. The term derives from the Greek words em (inside), peri (around), and polemai (to wander), literally meaning "wandering within," and was first coined in 1956 by Humble et al. to describe the apparent movement of lymphocytes inside larger cells in acute monocytic leukemia.[30] This process differs from phagocytosis, as the engulfed cell is not digested and can often exit the host cell intact.[31] The mechanism of emperipolesis involves the invagination of the host cell's plasma membrane to form a non-phagocytic vacuole that accommodates the invading cell, a process that is typically reversible and initiated by the inner cell. Cytoskeletal dynamics play a central role, with rearrangements mediated by proteins such as ezrin, E-cadherin, and the β2-integrin/ICAM-1 pathway facilitating attachment and entry. This phenomenon is frequently observed in histiocytes and megakaryocytes but also occurs in cancer cells, where the internalized cell resides temporarily within a single-membrane-bound compartment.[32][33][34] Biologically, emperipolesis supports cell survival by shielding the internalized cell from apoptosis and may contribute to immune tolerance, as seen in "suicidal emperipolesis," where autoreactive CD8+ T cells invade hepatocytes and are subsequently degraded to prevent autoimmunity. In tumor microenvironments, it aids cancer cell invasion and immune evasion by engulfing lymphocytes or natural killer cells. A hallmark example is its role in Rosai-Dorfman disease, a rare histiocytic disorder where histiocytes engulf intact lymphocytes and plasma cells to modulate local immune responses.[35][36] Diagnostically, emperipolesis is a critical histological feature for identifying Rosai-Dorfman disease, particularly in lymph node biopsies showing histiocytes with embedded, non-degraded lymphocytes. It also appears in certain lymphomas, such as T-cell lymphomas, serving as a distinguishing marker in differential diagnoses from other histiocytic proliferations.[37][38]Trogocytosis

Trogocytosis is the process by which one cell actively extracts and acquires membrane fragments, along with associated proteins and lipids, from the surface of an adjacent cell through direct cell-cell contact.[39] This phenomenon, derived from the Greek word "trogo," meaning "to gnaw" or "nibble," was first formally described and named in the context of immune cells in 2003, although earlier observations of similar membrane transfers date back to the late 1970s in non-immune systems.[40] The transfer typically occurs rapidly, within minutes, and is mediated by receptor-ligand interactions at the immunological synapse, involving actin cytoskeleton reorganization, phosphorylation events, and signaling molecules such as PI3K and GTPases.[41] In immune contexts, it often features the exchange of major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-peptide complexes, enabling the recipient cell to incorporate functional surface molecules from the donor.[39] The mechanism of trogocytosis relies on the formation of a stable immunological synapse between cells, where the acceptor cell "nibbles" membrane patches from the donor without causing cell death or full engulfment.[42] This process is energy-dependent and can be unidirectional or bidirectional, driven by specific interactions like T-cell receptor (TCR)-MHC binding or Fcγ receptor-antibody complexes, leading to the internalization of acquired material in the recipient cell.[41] The speed of transfer, often completing in under 5-15 minutes, allows for dynamic modulation of cell surfaces during brief encounters.[39] Biologically, trogocytosis plays key roles in immune regulation, particularly in antigen presentation, T-cell activation, and overall immune homeostasis. In T cells, it facilitates the acquisition of MHC-peptide complexes and costimulatory molecules (e.g., CD80, CD86) from antigen-presenting cells, prolonging TCR signaling, enhancing activation, and promoting differentiation into subsets like Th2 or regulatory T cells (Tregs).[39] Natural killer (NK) cells utilize trogocytosis to strip MHC class I molecules from target cells, thereby modulating cytotoxicity and self-tolerance, while also acquiring chemokine receptors like CCR7 to improve migration.[41] Dendritic cells engage in trogocytosis to "cross-dress" with peptide-MHC complexes from other cells, enabling efficient antigen presentation to naive T cells without de novo processing.[39] These exchanges can generate hybrid-like cells with mixed surface phenotypes, altering their functional capabilities and contributing to immune modulation, such as limiting excessive T-cell proliferation or inducing tolerance.[42] Dysregulated trogocytosis has been implicated in autoimmunity, for instance, by promoting Th17 cell polarization in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis models.[39] Experimentally, trogocytosis is detected primarily through flow cytometry, where donor cells are labeled with fluorescent membrane dyes (e.g., PKH26) or antigen-specific markers, and transfer is quantified by the appearance of these labels on acceptor cells post-contact.[41] This method allows for real-time assessment of transfer efficiency and specificity, often combined with microscopy to visualize synapse formation.[39]Efferocytosis

Efferocytosis is the process by which phagocytic cells, such as macrophages and epithelial cells, recognize and engulf apoptotic cells to maintain tissue integrity and prevent inflammatory responses.[43] The term was coined in 2003 by researchers Aimee M. deCathelineau and Peter M. Henson, derived from the Latin word "effere," meaning "to take to the grave" or "to carry away," emphasizing the burial-like clearance of dying cells.[29] This mechanism builds briefly on general phagocytosis principles, where apoptotic cells are specifically targeted for removal without triggering inflammation, unlike the clearance of necrotic cells.[44] The process begins with the exposure of "eat-me" signals on the surface of apoptotic cells, primarily the phospholipid phosphatidylserine (PS), which flips from the inner to the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane during apoptosis.[45] Phagocytes detect PS through bridging molecules and receptors, including TAM family receptors (Tyro3, Axl, and Mer), which facilitate direct or indirect binding and promote cytoskeletal rearrangements for engulfment.[46] Once internalized, the apoptotic cargo is degraded in phagosomes, and the phagocyte releases anti-inflammatory mediators, such as transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), to suppress pro-inflammatory cytokine production and promote tissue repair.[47] This engulfment is notably more efficient than the clearance of necrotic cells, as it occurs rapidly—often within minutes—to avert secondary necrosis and the release of damage-associated molecular patterns that could exacerbate inflammation.[48] Efferocytosis plays crucial roles in tissue homeostasis by ensuring the daily clearance of billions of apoptotic cells without eliciting immune activation, thus supporting organ development and resolving inflammation.[49] Defects in this process contribute to chronic inflammation and autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), where impaired PS recognition leads to accumulation of uncleared apoptotic cells and autoantibody production against nuclear antigens.[50] The mechanism is evolutionarily conserved, with homologous pathways identified in invertebrates like the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, where genes such as ced-1 to ced-10 mediate apoptotic cell engulfment, underscoring its fundamental importance across metazoans.[51]Cytokinesis

Cytokinesis is the final phase of cell division in which the cytoplasm of a single parent cell divides to produce two genetically identical daughter cells, ensuring the proper partitioning of cellular components after nuclear division. This process is essential for multicellular organism development, tissue growth, and asexual reproduction in unicellular organisms. In eukaryotic cells, cytokinesis is tightly coordinated with mitosis to prevent errors in chromosome segregation and cytoplasmic distribution.[52] In animal cells, cytokinesis primarily occurs through the formation of a contractile ring composed of actin filaments and myosin II motors, which assembles at the cell equator during late anaphase or telophase. This ring, often likened to a purse string, constricts under the force generated by myosin II walking along actin filaments, progressively pinching the plasma membrane inward to form a cleavage furrow that ultimately separates the daughter cells. The assembly and positioning of the contractile ring are regulated by Rho GTPases, particularly RhoA, which activates downstream effectors like formins for actin polymerization and ROCK kinase for myosin activation; RhoA localization is controlled by guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) such as ECT2 and GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) like MgcRacGAP, often guided by the mitotic spindle. In plant cells, cytokinesis differs markedly due to the rigid cell wall, relying instead on the formation of a cell plate: Golgi-derived vesicles carrying cell wall precursors accumulate at the division site, fuse along a microtubule-based phragmoplast structure, and expand centrifugally to form a new cell wall that partitions the cytoplasm. Actin filaments support vesicle delivery in plants, and while Rho GTPases play a minor role, kinesins and microtubule-associated proteins ensure precise vesicle trafficking. Both mechanisms involve elements of vesicular transport, such as membrane addition during furrow ingression in animals or vesicle fusion in plants.[52] The biological role of cytokinesis extends beyond mere division, as it guarantees equitable distribution of organelles, cytosol, and other cytoplasmic contents, which is crucial for daughter cell viability and function. Failures in cytokinesis can result in binucleate or multinucleate cells, leading to genomic instability and conditions like tetraploidy, which is implicated in cancer progression; for instance, defects in Rho GTPase signaling or contractile ring components have been linked to tumorigenesis in p53-deficient models. Cytokinesis is temporally regulated to align with mitosis, typically initiating after anaphase chromosome separation when cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (Cdk1) activity declines, allowing central spindle formation and RhoA activation. Key regulators include Aurora B and Polo-like kinase 1 (Plk1), which phosphorylate components to fine-tune furrow ingression and abscission. Variations between animal and plant cytokinesis reflect adaptations to cellular architecture—furrow-based constriction in flexible animal cells versus plate-based separation in walled plant cells—yet both ensure precise division plane selection via microtubule cues.[52] Cytokinesis was first observed through light microscopy in the 1880s, with Walther Flemming's detailed descriptions of chromosome behavior during animal cell division highlighting the cleavage process in salamander epithelial cells.[53]Abnormal Cell Counts

Leukocytosis

Leukocytosis refers to an elevated white blood cell (WBC) count beyond the normal range, defined as greater than 11 × 10⁹/L in adults, though thresholds may vary slightly by laboratory standards and patient age.[54] The typical normal range for WBCs in adults is 4–11 × 10⁹/L, with newborns and children exhibiting higher baseline counts that decrease with age.[54] This condition arises from increased production, release from bone marrow storage, or reduced margination of leukocytes in circulation, often reflecting the body's response to physiological or pathological stimuli.[54] Causes of leukocytosis are broadly classified as reactive or neoplastic. Reactive leukocytosis, the most common form, results from non-malignant triggers such as infections (bacterial, viral, or fungal), inflammation, tissue injury, stress, exercise, or medications like corticosteroids.[54] For instance, bacterial infections frequently provoke a rapid rise in neutrophils as part of the acute inflammatory response.[55] In contrast, neoplastic causes involve malignant proliferation, such as in chronic myelogenous leukemia or other myeloproliferative disorders, where uncontrolled clonal expansion leads to persistently high counts.[54] The distinction is critical, as reactive forms are usually self-limiting once the trigger resolves, while neoplastic cases require oncologic intervention.[54] Leukocytosis is subclassified by the predominant WBC type identified in the differential count, with measurement performed via complete blood count (CBC) analysis, often supplemented by a peripheral blood smear for morphological assessment.[54] Neutrophilia, an increase in neutrophils exceeding 7.7 × 10⁹/L, predominates in bacterial infections and acute inflammation, accounting for the majority of reactive cases.[54] Lymphocytosis, marked by elevated lymphocytes, is more typical of viral infections like Epstein-Barr virus or chronic conditions such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia.[54] Other subtypes include monocytosis, eosinophilia, and basophilia, each linked to specific etiologies like parasitic infections or allergic responses.[54] First recognized in the 19th century alongside microscopic descriptions of leukocytes by scientists like Max Schultze in 1865, leukocytosis remains a key hematologic finding today.[56] Clinically, leukocytosis serves as an important diagnostic marker for underlying pathology, prompting further evaluation to identify infections, inflammatory diseases, or malignancies, and it correlates with increased morbidity in conditions like sepsis.[55] Symptoms vary by cause but may include fever, fatigue, chills, or localized signs of infection; in severe neoplastic cases, hyperleukocytosis (>100 × 10⁹/L) can lead to complications like leukostasis with organ dysfunction.[54] It is a frequent laboratory abnormality in hospitalized patients with infections, observed in over half of those presenting with marked elevations.[57] Treatment targets the root cause—antibiotics for bacterial infections, anti-inflammatories for reactive processes, or chemotherapy and supportive measures like leukapheresis for malignancies—while monitoring via serial CBCs ensures resolution.[54] This condition underscores the role of leukocytes in immune defense, including migration processes like diapedesis to infection sites.[54]Thrombocytosis

Thrombocytosis is defined as an elevated platelet count in the peripheral blood, typically exceeding 450 × 10⁹/L, in contrast to the normal range of 150–450 × 10⁹/L.[58][59] This condition arises from two primary categories: reactive (secondary) thrombocytosis, which accounts for 80–90% of cases and results from underlying non-clonal disorders, and primary thrombocytosis, a clonal myeloproliferative neoplasm known as essential thrombocythemia.[60][61] Reactive forms are commonly triggered by conditions such as iron deficiency anemia, post-surgical recovery, infections, inflammation, or tissue damage, where cytokines like interleukin-6 stimulate megakaryocyte proliferation without inherent bone marrow pathology.[62][63] In essential thrombocythemia, autonomous megakaryocyte hyperplasia drives the platelet excess, often linked to mutations in genes regulating hematopoiesis.[64] The clinical risks of thrombocytosis include both thrombotic complications, such as stroke, myocardial infarction, or deep vein thrombosis due to heightened platelet aggregation, and paradoxical bleeding tendencies from dysfunctional platelets or acquired von Willebrand syndrome in extreme cases.[59][61] Diagnosis involves confirming the elevated count through complete blood count analysis, followed by peripheral blood smear to exclude pseudothrombocytosis or platelet clumping, and further evaluation like bone marrow biopsy for primary cases to identify megakaryocytic hyperplasia and rule out other myeloproliferative disorders.[65] In primary thrombocytosis, approximately 50–55% of patients harbor the JAK2 V617F mutation, which activates the Janus kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription pathway, promoting uncontrolled cell proliferation; other mutations like CALR or MPL occur in additional subsets.[58][66] Management of thrombocytosis focuses on addressing the underlying cause in reactive cases, where platelet counts often normalize with resolution of the trigger, such as iron supplementation for deficiency or antibiotics for infection.[62] For essential thrombocythemia, risk-stratified therapy includes low-dose aspirin to mitigate thrombosis in low-risk patients, while high-risk individuals (e.g., age >60 years or prior thrombosis) receive cytoreductive agents like hydroxyurea to reduce platelet counts and prevent complications.[64] The term thrombocytosis emerged in the medical literature during the 1930s, reflecting early recognition of platelet count abnormalities in hematologic contexts, though secondary forms predominate in clinical practice.[67] As part of broader abnormal cell count disorders, thrombocytosis specifically impacts hemostasis through platelet dysregulation.[61]Erythrocytosis

Erythrocytosis refers to an abnormal increase in the number of circulating red blood cells (erythrocytes), resulting in elevated hematocrit levels and increased blood viscosity.[68] This condition, also known as polycythemia, contrasts with relative increases due to plasma volume reduction by featuring an absolute expansion of red cell mass.[69] In adult males, normal red blood cell counts range from 4.5 to 5.9 × 10¹²/L, and values exceeding this threshold indicate erythrocytosis.[70] Erythrocytosis is classified into primary and secondary forms based on underlying mechanisms. Primary erythrocytosis arises from autonomous proliferation of erythroid progenitor cells due to intrinsic defects, most commonly polycythemia vera (PV), a myeloproliferative neoplasm frequently driven by the JAK2 V617F mutation in over 95% of cases.[71] In contrast, secondary erythrocytosis results from extrinsic stimuli increasing erythropoietin (EPO) production, such as chronic hypoxia from high-altitude living, smoking, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or cyanotic heart disease; it can also stem from EPO-secreting tumors like renal cell carcinoma.[72] Secondary forms are more prevalent in populations residing at high altitudes, where adaptive erythrocytosis enhances oxygen delivery but can become excessive.[73] Common symptoms include headaches, dizziness, fatigue, visual disturbances, and pruritus, often exacerbated by the hyperviscous state of the blood.[74] Thrombotic complications, such as deep vein thrombosis or stroke, represent serious manifestations due to heightened blood viscosity and platelet activation, with hematocrit levels above 55% exponentially elevating stroke risk.[75] Treatment primarily involves phlebotomy to reduce red cell mass and alleviate symptoms, alongside low-dose aspirin to mitigate thrombotic risk; in primary cases, cytoreductive therapies like hydroxyurea may be added for high-risk patients.[76] Clinically, distinguishing primary from secondary erythrocytosis is crucial, as EPO levels are typically suppressed in primary forms (< upper limit of normal) and elevated in secondary ones (>15 mU/mL), guiding targeted management.[77] The condition was first described in 1892 by Henri Vaquez as a distinct entity involving chronic erythrocytosis, laying the foundation for recognizing PV as a primary disorder.[78] Overall, erythrocytosis significantly impacts cardiovascular health, underscoring the need for prompt diagnosis to prevent thrombotic events.[79]Abnormal Cell Morphologies

Microcytosis

Microcytosis is defined as the presence of red blood cells (RBCs) that are smaller than normal, typically indicated by a mean corpuscular volume (MCV) less than 80 fL on a complete blood count, with normal MCV ranging from 80 to 100 fL.[80] This condition often results in microcytic anemia, where RBCs appear hypochromic due to reduced hemoglobin content, giving them a pale appearance on blood smears.[81] The most common causes include iron deficiency anemia and thalassemia trait, with iron deficiency being the leading worldwide etiology due to impaired hemoglobin synthesis from inadequate iron availability.[82] Microcytic anemias represent one of the most prevalent forms of anemia globally, particularly in regions with high rates of nutritional deficiencies.[83] Diagnosis of microcytosis involves a peripheral blood smear, which reveals small, pale RBCs with increased central pallor, confirming the hypochromic microcytic morphology.[84] Low serum ferritin levels, typically below 30 ng/mL, are a key indicator of iron deficiency as the underlying cause, distinguishing it from other etiologies like thalassemia, which may require hemoglobin electrophoresis for confirmation.[85] Additional iron studies, such as elevated total iron-binding capacity and low serum iron, further support the diagnosis in iron-deficient cases.[86] Clinically, microcytosis contributes to anemia symptoms including fatigue, weakness, pallor, tachycardia, and exertional dyspnea, arising from reduced oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood.[87] In severe cases, it can lead to complications like heart failure or developmental delays in children.[81] Treatment primarily focuses on addressing the cause; for iron deficiency, oral iron supplementation (e.g., ferrous sulfate 325 mg daily) is effective, often normalizing MCV within months, though thalassemia management may involve genetic counseling rather than iron therapy.[84] Microcytosis is a key feature in the spectrum of abnormal RBC morphologies, reflecting defects in cell size rather than count or shape variations.[80]Macrocytosis

Macrocytosis is defined as the presence of enlarged red blood cells (erythrocytes), typically identified by a mean corpuscular volume (MCV) exceeding 100 femtoliters (fL) on a complete blood count.[88] This condition arises from disruptions in erythropoiesis, particularly impaired DNA synthesis leading to asynchronous maturation of the red blood cell nucleus and cytoplasm.[89] It contrasts with microcytosis, where red blood cells are smaller than normal.[90] The primary causes of macrocytosis include vitamin B12 and folate deficiencies, chronic alcoholism, and hypothyroidism.[88] Vitamin B12 deficiency often results from inadequate dietary intake (e.g., in strict vegans), malabsorption due to pernicious anemia or gastrointestinal disorders like celiac disease, or interference from medications such as metformin.[88] Folate deficiency is commonly linked to poor nutrition, exacerbated in alcoholics or elderly individuals, as alcohol impairs folate absorption and metabolism.[88] Hypothyroidism contributes through multifactorial effects on red blood cell production, though the exact mechanisms remain incompletely understood.[88] Diagnosis begins with a peripheral blood smear, which reveals characteristic oval macrocytes and hypersegmented neutrophils in megaloblastic forms of macrocytosis.[89] Additional laboratory tests assess serum vitamin B12, folate levels, and markers like methylmalonic acid or homocysteine to confirm deficiencies.[89] In cases requiring further evaluation, bone marrow aspiration and biopsy show a hypercellular marrow with megaloblastic changes, including large erythroid precursors and impaired maturation.[91] Clinically, macrocytosis frequently manifests as megaloblastic anemia, with symptoms including fatigue, pallor, dyspnea, and glossitis due to ineffective red blood cell production.[89] In vitamin B12 deficiency specifically, neurological complications such as peripheral neuropathy, paresthesias, ataxia, and cognitive deficits arise from subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord.[88] These symptoms underscore the importance of early detection, as untreated B12 deficiency can lead to irreversible neurologic damage.[89] Macrocytosis occurs in 1.7% to 3.6% of the general population, with higher prevalence among males and older adults.[88] It is often asymptomatic and detected incidentally but serves as a marker for underlying pathology.[92] Treatment addressing the root cause—such as oral or intramuscular vitamin B12 (1000 µg daily initially) and folate (1-5 mg daily) supplementation, or alcohol abstinence—typically reverses macrocytosis and associated anemia within 4-8 weeks, though full hematologic recovery may take months.[89]Anisocytosis

Anisocytosis refers to the variation in size among red blood cells (erythrocytes) in the peripheral blood, indicating heterogeneous erythropoiesis where cells produced by the bone marrow differ significantly in volume.[93] This condition is quantified using the red blood cell distribution width (RDW), a parameter from automated complete blood counts (CBC) that measures the coefficient of variation in erythrocyte volume; normal values range from 11.5% to 14.5%, with levels exceeding 14.5% signifying notable anisocytosis.[94] The term originates from the Greek "aniso-" meaning unequal, reflecting the disparity in cell dimensions observed under microscopy.[95] Common causes include mixed anemias, such as those combining iron deficiency with vitamin B12 or folate shortages, which disrupt uniform hemoglobin synthesis and lead to a broad spectrum of cell sizes.[96] Sideroblastic anemia, characterized by defective heme production in erythroid precursors, also promotes anisocytosis through the accumulation of iron-ringed sideroblasts and variable cell maturation.[93] Post-hemorrhage states contribute as well, with regenerative reticulocytosis introducing larger, immature cells amid smaller mature erythrocytes, exacerbating size variation.[94] Nutritional deficiencies, particularly in iron, vitamin B12, or folate, are frequent triggers, as they impair consistent erythropoiesis and are prevalent in conditions like malnutrition or malabsorption syndromes.[96] Diagnosis relies on automated hematology analyzers that compute RDW during routine CBC testing, providing an objective index of size heterogeneity without manual intervention.[93] Peripheral blood smears complement this by visually demonstrating anisocytosis through the presence of erythrocytes ranging from small microcytes to large macrocytes, aiding in the differentiation from uniform size abnormalities.[96] Clinically, anisocytosis functions primarily as a diagnostic marker for underlying hematologic or systemic disorders rather than a standalone pathology, often correlating with ineffective erythropoiesis and reduced oxygen-carrying capacity that manifests as anemia symptoms like fatigue.[94] It has no specific treatment; management focuses on addressing the root cause, such as nutritional supplementation for deficiencies or iron chelation for sideroblastic anemia, thereby normalizing RBC production over time.[93] Elevated RDW in anisocytosis may also signal broader risks, including inflammation or cardiovascular complications, underscoring the need for comprehensive evaluation.[96]Spherocytosis

Hereditary spherocytosis (HS) is a congenital hemolytic anemia characterized by spherical red blood cells resulting from defects in the erythrocyte membrane cytoskeleton.[97] These defects primarily arise from mutations in genes encoding key proteins such as ankyrin-1 (ANK1), alpha-spectrin (SPTA1), beta-spectrin (SPTB), band 3 (SLC4A1), and protein 4.2 (EPB42), which disrupt the vertical linkages between the lipid bilayer and the spectrin-actin cytoskeleton.[98] Consequently, affected erythrocytes lose membrane surface area relative to volume, transforming their normal biconcave disc shape into rigid spherocytes that are prone to splenic sequestration and premature destruction, leading to extravascular hemolysis.[99] HS exhibits an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern in approximately 75% of cases, with the remaining instances involving autosomal recessive transmission or de novo mutations.[100] It is the most common inherited hemolytic anemia in populations of Northern European descent, with a prevalence estimated at 1 in 2000 to 1 in 5000 individuals.[101] The severity varies widely, from mild compensated hemolysis to severe transfusion-dependent anemia, often correlating with the degree of membrane instability and protein deficiency.[102] Diagnosis of HS relies on a combination of clinical evaluation and laboratory tests, as no single assay is definitive. Peripheral blood smears typically reveal spherocytes, which appear as small, dense red blood cells without central pallor.[103] The osmotic fragility test (OFT), particularly the incubated version, demonstrates increased erythrocyte fragility to hypotonic solutions due to the reduced surface-to-volume ratio of spherocytes.[104] Flow cytometric assays, such as the eosin-5-maleimide (EMA) binding test, show decreased fluorescence intensity from reduced band 3 protein expression, offering high sensitivity and specificity for screening.[105] Additionally, elevated mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC) above 37 g/dL is a characteristic finding, reflecting cellular dehydration.[106] Genetic testing can confirm specific mutations but is reserved for atypical cases.[107] Clinically, HS manifests as chronic hemolysis with intermittent exacerbations triggered by infections or stressors, resulting in jaundice from unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia, pallor, and fatigue.[97] Splenomegaly develops in most patients due to red cell trapping, and complications include cholelithiasis from bilirubin gallstones and aplastic crises from parvovirus B19 infection.[108] Splenectomy effectively halts hemolysis and corrects anemia in moderate to severe cases by removing the site of spherocyte destruction, though it is typically deferred until after age 5 to minimize infection risks and may require partial splenectomy in children to preserve immune function.[109] Supportive care includes folic acid supplementation and monitoring for complications, with erythropoietin or transfusions used in severe anemia.[110] As a morphological variant observed in various anemias, HS is distinguished by its hereditary membrane etiology.[111]Ovalocytosis

Ovalocytosis, also known as hereditary elliptocytosis (HE), is an inherited disorder of the red blood cell (RBC) membrane characterized by the presence of elliptical or oval-shaped erythrocytes, resulting from genetic defects that impair membrane integrity and elasticity.[112] This condition falls under the broader category of RBC membrane disorders and leads to varying degrees of hemolysis, though often mild or compensated.[113] The primary genetic defects in HE involve mutations in genes encoding key membrane skeletal proteins, most commonly α-spectrin (approximately 65% of cases), β-spectrin (30%), and protein 4.1 (5%), with less frequent involvement of band 3 (anion exchanger 1) or glycophorin C.[112] These mutations disrupt the vertical and horizontal linkages of the RBC cytoskeleton, causing mechanical instability and the characteristic elliptical morphology without significantly altering cell volume or hydration.[114] As a result, affected RBCs exhibit reduced deformability, leading to mild extravascular hemolysis in many individuals, though the majority remain asymptomatic due to compensatory erythropoiesis.[112] Diagnosis of ovalocytosis relies primarily on microscopic examination of a peripheral blood smear, which reveals 15% to 100% elliptocytes—often described as cigar-shaped or rod-like RBCs—alongside occasional poikilocytes or fragments in more severe cases.[112] Unlike spherocytosis, osmotic fragility testing typically shows normal results in HE, reflecting preserved surface-to-volume ratio despite the shape abnormality; advanced assessments like ektacytometry may demonstrate reduced deformability under shear stress, and SDS-PAGE electrophoresis can identify specific protein defects.[112] Genetic testing confirms mutations in implicated genes, particularly in atypical or familial presentations.[115] Clinically, most individuals with ovalocytosis (about 90%) are asymptomatic or experience only mild, compensated hemolysis without anemia, though rare severe forms—such as hereditary pyropoikilocytosis or compound heterozygotes—can present with significant hemolytic anemia, jaundice, splenomegaly, and gallstones, especially in infancy.[112] Neonatal jaundice may occur due to transient hemolysis, but long-term complications are uncommon without splenectomy, which is reserved for severe cases to reduce hemolysis.[116] A notable variant is Southeast Asian ovalocytosis (SAO), caused by a specific 27-base pair deletion in the band 3 gene (SLC4A1), resulting in a 9-amino-acid deletion that rigidifies the RBC membrane and confers resistance to invasion by Plasmodium falciparum and other malaria parasites.[117] This adaptation explains the higher prevalence of SAO (5% to 25%) in malaria-endemic regions like Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, and parts of Southeast Asia, compared to the global prevalence of HE at approximately 1 in 2,000 to 1 in 4,000.[112] Overall, HE affects diverse populations but is more common in those of African or Mediterranean descent for non-SAO forms.[112]Drepanocytosis

Drepanocytosis, also known as sickle cell anemia (HbSS), is a severe inherited disorder characterized by abnormal hemoglobin that causes red blood cells to assume a sickle shape under certain conditions. It results from a point mutation in the HBB gene on chromosome 11, substituting valine for glutamic acid at the sixth position of the beta-globin chain, leading to the production of hemoglobin S (HbS).[118][119][120] In the deoxygenated state, HbS molecules polymerize into rigid fibers, distorting erythrocytes into crescent-like forms that impair flexibility and promote vascular obstruction.[120][121] Diagnosis typically involves hemoglobin electrophoresis, which identifies the presence of HbS by its altered electrophoretic mobility at alkaline pH.[122] Peripheral blood smears, particularly under reduced oxygen conditions, reveal characteristic sickle-shaped erythrocytes (drepanocytes) alongside target cells and Howell-Jolly bodies, confirming the morphological abnormality.[120] Newborn screening using high-performance liquid chromatography or isoelectric focusing is standard for early detection, enabling prompt intervention.[123] Clinically, drepanocytosis manifests as chronic hemolytic anemia due to shortened red blood cell survival and recurrent vaso-occlusive crises, where sickled cells aggregate and block microvasculature, causing severe pain, tissue ischemia, and organ damage.[124] Hydroxyurea, a key disease-modifying therapy, increases fetal hemoglobin levels, reduces HbS polymerization, and decreases the frequency of crises, hospitalizations, and acute chest syndrome by up to 50%.[125][126] Recent advances include gene therapies such as exagamglogene autotemcel (Casgevy) and lovotibeglogene autotemcel (Lyfgenia), approved by the FDA in late 2023 for patients aged 12 and older with severe disease, offering potential for long-term disease modification or cure by editing hematopoietic stem cells.[127][128] Heterozygotes carrying one HbS allele (sickle cell trait) exhibit a survival advantage in malaria-endemic regions, as the altered red cells inhibit Plasmodium falciparum growth, balancing the allele's persistence despite homozygous disease severity.[129][130] First described in 1910 by James B. Herrick, who observed peculiar elongated red cells in a patient's blood smear, drepanocytosis affects approximately 1 in 500 African American births in the United States.[131][132] Advances in care, including routine transfusions, antimicrobial prophylaxis, and emerging gene therapies, have extended median life expectancy to approximately 50-60 years or more in high-resource settings as of 2024, though disparities persist globally.[133][134][135]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/cytosis