Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Myogenesis

View on Wikipedia

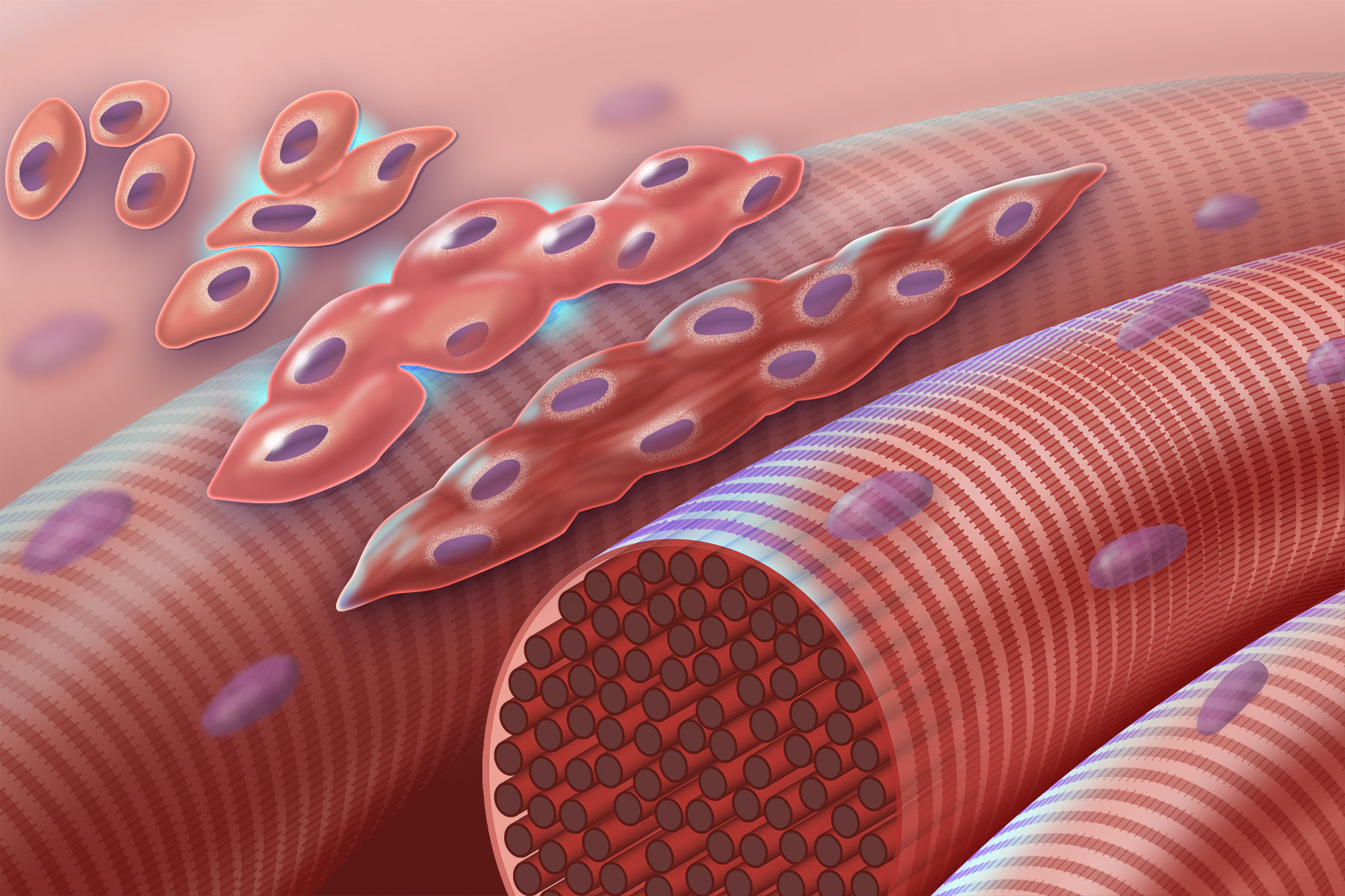

Myogenesis is the formation of skeletal muscular tissue, particularly during embryonic development. Muscle fibers generally form through the fusion of precursor myoblasts into multinucleated fibers called myotubes. In the early development of an embryo, myoblasts can either proliferate, or differentiate into a myotube. What controls this choice in vivo is generally unclear. If placed in cell culture, most myoblasts will proliferate if enough fibroblast growth factor (FGF) or another growth factor is present in the medium surrounding the cells. When the growth factor runs out, the myoblasts cease division and undergo terminal differentiation into myotubes.

Myoblast differentiation proceeds in stages. The first stage involves cell cycle exit and the commencement of expression of certain genes. The second stage of differentiation involves the alignment of the myoblasts with one another. Studies have shown that even rat and chick myoblasts can recognise and align with one another, suggesting evolutionary conservation of the mechanisms involved.[1] The third stage is the actual cell fusion itself. In this stage, the presence of calcium ions is critical. Fusion in humans is aided by a set of metalloproteinases coded for by the ADAM12 gene, and a variety of other proteins. Fusion involves recruitment of actin to the plasma membrane, followed by close apposition and creation of a pore that subsequently rapidly widens.

Genes and their protein products that are expressed during the process include: myocyte enhancer factors, myogenic regulatory factors, and serum response factor. Expression of skeletal alpha-actin is also regulated by the androgen receptor; steroids can thereby regulate myogenesis.[2]

Overview

[edit]There are a number of stages (listed below) of muscle development, or myogenesis.[3] Each stage has various associated genetic factors lack of which will result in muscular defects.

Stages

[edit]| Stage | Associated Genetic Factors |

|---|---|

| Delamination | PAX3, c-Met |

| Migration | c-met/HGF, LBX1 |

| Proliferation | PAX3, c-Met, Mox2, MSX1, Six1/4, Myf5, MyoD |

| Determination | Myf5 and MyoD |

| Differentiation | Myogenin, MCF2, Six1/4, MyoD, Myf6 |

| Specific Muscle Formation | Lbx1, Meox2 |

| Satellite Cells | PAX7 |

Delamination

[edit]

Associated Genetic Factors: PAX3 and c-Met

Mutations in PAX3 can cause a failure in c-Met expression. Such a mutation would result in a lack of lateral migration.

PAX3 mediates the transcription of c-Met and is responsible for the activation of MyoD expression—one of the functions of MyoD is to promote the regenerative ability of satellite cells (described below).[3] PAX3 is generally expressed at its highest levels during embryonic development and is expressed at a lesser degree during the fetal stages; it is expressed in migrating hypaxial cells and dermomyotome cells, but is not expressed at all during the development of facial muscle.[3] Mutations in Pax3 can cause a variety of complications including Waardenburg syndrome I and III as well as craniofacial-deafness-hand syndrome.[3] Waardenburg syndrome is most often associated with congenital disorders involving the intestinal tract and spine, an elevation of the scapula, among other symptoms. Each stage has various associated genetic factors without which will result in muscular defects.[3]

Migration

[edit]Associated Genetic Factors: c-Met/HGF and LBX1

Mutations in these genetic factors causes a lack of migration.

LBX1 is responsible for the development and organization of muscles in the dorsal forelimb as well as the movement of dorsal muscles into the limb following delamination.[3] Without LBX1, limb muscles will fail to form properly; studies have shown that hindlimb muscles are severely affected by this deletion while only flexor muscles form in the forelimb muscles as a result of ventral muscle migration.[3]

c-Met is a tyrosine kinase receptor that is required for the survival and proliferation of migrating myoblasts. A lack of c-Met disrupts secondary myogenesis and—as in LBX1—prevents the formation of limb musculature.[3] It is clear that c-Met plays an important role in delamination and proliferation in addition to migration. PAX3 is needed for the transcription of c-Met.[3]

Proliferation

[edit]Associated Genetic Factors: PAX3, c-Met, Mox2, MSX1, Six, Myf5, and MyoD

Mox2 (also referred to as MEOX-2) plays an important role in the induction of mesoderm and regional specification.[3] Impairing the function of Mox2 will prevent the proliferation of myogenic precursors and will cause abnormal patterning of limb muscles.[4] Specifically, studies have shown that hindlimbs are severely reduced in size while specific forelimb muscles will fail to form.[3]

Myf5 is required for proper myoblast proliferation.[3] Studies have shown that mice muscle development in the intercostal and paraspinal regions can be delayed by inactivating Myf-5.[3] Myf5 is considered to be the earliest expressed regulatory factor gene in myogenesis. If Myf-5 and MyoD are both inactivated, there will be a complete absence of skeletal muscle.[3] These consequences further reveal the complexity of myogenesis and the importance of each genetic factor in proper muscle development.

Determination

[edit]Associated Genetic Factors: Myf5 and MyoD

One of the most important stages in myogenesis determination requires both Myf5 and MyoD to function properly in order for myogenic cells to progress normally. Mutations in either associated genetic factor will cause the cells to adopt non-muscular phenotypes.[3]

As stated earlier, the combination of Myf5 and MyoD is crucial to the success of myogenesis. Both MyoD and Myf5 are members of the myogenic bHLH (basic helix-loop-helix) proteins transcription factor family.[5] Cells that make myogenic bHLH transcription factors (including MyoD or Myf5) are committed to development as a muscle cell.[6] Consequently, the simultaneous deletion of Myf5 and MyoD also results in a complete lack of skeletal muscle formation.[6] Research has shown that MyoD directly activates its own gene; this means that the protein made binds the myoD gene and continues a cycle of MyoD protein production.[6] Meanwhile, Myf5 expression is regulated by Sonic hedgehog, Wnt1, and MyoD itself.[3] By noting the role of MyoD in regulating Myf5, the crucial interconnectedness of the two genetic factors becomes clear.[3]

Serum response factor is needed for myogenesis and muscle development.[7] Interaction of SRF with other proteins, such as steroid hormone receptors, may contribute to regulation of muscle growth by steroids.[8]

Differentiation

[edit]Associated genetic factors: Myogenin, Mcf2, Six, MyoD, and Myf6

Mutations in these associated genetic factors will prevent myocytes from advancing and maturing.

Myogenin (also known as Myf4) is required for the fusion of myogenic precursor cells to either new or previously existing fibers.[3] In general, myogenin is associated with amplifying expression of genes that are already being expressed in the organism. Deleting myogenin results in nearly complete loss of differentiated muscle fibers and severe loss of skeletal muscle mass in the lateral/ventral body wall.[3]

Myf-6 (also known as MRF4 or Herculin) is important to myotube differentiation and is specific to skeletal muscle.[3] Mutations in Myf-6 can provoke disorders including centronuclear myopathy and Becker muscular dystrophy.[3]

Specific muscle formation

[edit]Associated genetic factors: LBX1 and Mox2

In specific muscle formation, mutations in associated genetic factors begin to affect specific muscular regions. Because of its large responsibility in the movement of dorsal muscles into the limb following delamination, mutation or deletion of Lbx1 results in defects in extensor and hindlimb muscles.[3] As stated in the Proliferation section, Mox2 deletion or mutation causes abnormal patterning of limb muscles. The consequences of this abnormal patterning include severe reduction in size of hindlimbs and complete absence of forelimb muscles.[3]

Satellite cells

[edit]Associated genetic factors: PAX7

Mutations in Pax7 will prevent the formation of satellite cells and, in turn, prevent postnatal muscle growth.[3]

Satellite cells are described as quiescent myoblasts and neighbor muscle fiber sarcolemma.[3] They are crucial for the repair of muscle, but have a very limited ability to replicate. Activated by stimuli such as injury or high mechanical load, satellite cells are required for muscle regeneration in adult organisms.[3] In addition, satellite cells have the capability to also differentiate into bone or fat. In this way, satellite cells have an important role in not only muscle development, but in the maintenance of muscle through adulthood.[3]

Skeletal muscle

[edit]During embryogenesis, the dermomyotome and/or myotome in the somites contain the myogenic progenitor cells that will evolve into the prospective skeletal muscle.[9] The determination of dermomyotome and myotome is regulated by a gene regulatory network that includes a member of the T-box family, tbx6, ripply1, and mesp-ba.[10] Skeletal myogenesis depends on the strict regulation of various gene subsets in order to differentiate the myogenic progenitors into myofibers. Basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factors, MyoD, Myf5, myogenin, and MRF4 are critical to its formation. MyoD and Myf5 enable the differentiation of myogenic progenitors into myoblasts, followed by myogenin, which differentiates the myoblast into myotubes.[9] MRF4 is important for blocking the transcription of muscle-specific promoters, enabling skeletal muscle progenitors to grow and proliferate before differentiating.

There are a number of events that occur in order to propel the specification of muscle cells in the somite. For both the lateral and medial regions of the somite, paracrine factors induce myotome cells to produce MyoD protein—thereby causing them to develop as muscle cells.[11] A transcription factor (TCF4) of connective tissue fibroblasts is involved in the regulation of myogenesis. Specifically, it regulates the type of muscle fiber developed and its maturations.[3] Low levels of TCF4 promote both slow and fast myogenesis, overall promoting the maturation of muscle fiber type. Thereby this shows the close relationship of muscle with connective tissue during the embryonic development.[12]

Regulation of myogenic differentiation is controlled by two pathways: the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway and the Notch/Hes pathway, which work in a collaborative manner to suppress MyoD transcription.[5] The O subfamily of the forkhead proteins (FOXO) play a critical role in regulation of myogenic differentiation as they stabilize Notch/Hes binding. Research has shown that knockout of FOXO1 in mice increases MyoD expression, altering the distribution of fast-twitch and slow-twitch fibers.[5]

Muscle fusion

[edit]Primary muscle fibers originate from primary myoblasts and tend to develop into slow muscle fibers.[3] Secondary muscle fibers then form around the primary fibers near the time of innervation. These muscle fibers form from secondary myoblasts and usually develop as fast muscle fibers. Finally, the muscle fibers that form later arise from satellite cells.[3]

Two genes significant in muscle fusion are Mef2 and the twist transcription factor. Studies have shown knockouts for Mef2C in mice lead to muscle defects in cardiac and smooth muscle development, particularly in fusion.[13] The twist gene plays a role in muscle differentiation.

The SIX1 gene plays a critical role in hypaxial muscle differentiation in myogenesis. In mice lacking this gene, severe muscle hypoplasia affected most of the body muscles, specifically hypaxial muscles.[14]

In myoblasts, PtdIns5P, produced by the lipid phosphatase MTM1, is rapidly metabolized by PI5P 4-kinase α into PI(4,5)P2, which accumulates at the plasma membrane. This accumulation facilitates the formation of podosome-like protrusions, where the fusogen Myomaker is localized, playing a crucial role in the spatiotemporal regulation of myoblast fusion.[15]

Protein synthesis and actin heterogeneity

[edit]There are 3 types of proteins produced during myogenesis.[4] Class A proteins are the most abundant and are synthesized continuously throughout myogenesis. Class B proteins are proteins that are initiated during myogenesis and continued throughout development. Class C proteins are those synthesized at specific times during development. Also 3 different forms of actin were identified during myogenesis.

Sim2, a BHLH-Pas transcription factor, inhibits transcription by active repression and displays enhanced expression in ventral limb muscle masses during chick and mouse embryonic development. It accomplishes this by repressing MyoD transcription by binding to the enhancer region, and prevents premature myogenesis.[16]

Delta1 expression in neural crest cells is necessary for muscle differentiation of the somites, through the Notch signaling pathway. Gain and loss of this ligand in neural crest cells results in delayed or premature myogenesis.[17]

Techniques

[edit]The significance of alternative splicing was elucidated using microarrary analysis of differentiating C2C12 myoblasts.[18] 95 alternative splicing events occur during C2C12 differentiation in myogenesis. Therefore, alternative splicing is necessary in myogenesis.

Systems approach

[edit]Systems approach is a method used to study myogenesis, which manipulates a number of different techniques like high-throughput screening technologies, genome wide cell-based assays, and bioinformatics, to identify different factors of a system.[9] This has been specifically used in the investigation of skeletal muscle development and the identification of its regulatory network.

Systems approach using high-throughput sequencing and ChIP-chip analysis has been essential in elucidating the targets of myogenic regulatory factors like MyoD and myogenin, their inter-related targets, and how MyoD acts to alter the epigenome in myoblasts and myotubes.[9] This has also revealed the significance of PAX3 in myogenesis, and that it ensures the survival of myogenic progenitors.[9]

This approach, using cell based high-throughput transfection assay and whole-mount in situ hybridization, was used in identifying the myogenetic regulator RP58, and the tendon differentiation gene, Mohawk homeobox.[9]

References

[edit]- ^ Yaffe, David; Feldman, Michael (1965). "The formation of hybrid multinucleated muscle fibers from myoblasts of different genetic origin". Developmental Biology. 11 (2): 300–317. doi:10.1016/0012-1606(65)90062-X. PMID 14332576.

- ^ Vlahopoulos S, Zimmer WE, Jenster G, Belaguli NS, Balk SP, Brinkmann AO, Lanz RB, Zoumpourlis VC, Schwartz RJ, et al. (2005). "Recruitment of the androgen receptor via serum response factor facilitates expression of a myogenic gene". J Biol Chem. 280 (9): 7786–92. doi:10.1074/jbc.M413992200. PMID 15623502.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad Pestronk, Alan. "Myogenesis & Muscle Regeneration". WU Neuromuscular. Washington University. Retrieved 2013-03-16.

- ^ a b Harovltch, Sharon (1975). "Myogenesis in primary cell cultures from Drosophila melanogaster: protein synthesis and actin heterogeneity during development". Cell. 66 (4): 1281–6. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(78)90210-6. PMID 418880. S2CID 10811840.

- ^ a b c Kitamura, Tadahiro; Kitamura YI; Funahashi Y; Shawber CJ; Castrillon DH; Kollipara R; DePinho RA; Kitajewski J; Accili D (4 September 2007). "A Foxo/Notch pathway controls myogenic differentiation and fiber type specification". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 117 (9): 2477–2485. doi:10.1172/JCI32054. PMC 1950461. PMID 17717603.

- ^ a b c Maroto, M; Reshef R; Münsterberg A E; Koester S; Goulding M; Lassar A B. (Apr 4, 1997). "Ectopic Pax-3 activates MyoD and Myf-5 expression in embryonic mesoderm and neural tissue". Cell. 89 (1): 139–148. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80190-7. PMID 9094722.

- ^ Li S, Czubryt MP, McAnally J, Bassel-Duby R, Richardson JA, Wiebel FF, Nordheim A, Olson EN (January 2005). "Requirement for serum response factor for skeletal muscle growth and maturation revealed by tissue-specific gene deletion in mice". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 (4): 1082–7. Bibcode:2005PNAS..102.1082L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0409103102. PMC 545866. PMID 15647354.

- ^ Vlahopoulos S, Zimmer WE, Jenster G, Belaguli NS, Balk SP, Brinkmann AO, Lanz RB, Zoumpourlis VC, Schwartz RJ (March 2005). "Recruitment of the androgen receptor via serum response factor facilitates expression of a myogenic gene". J. Biol. Chem. 280 (9): 7786–92. doi:10.1074/jbc.M413992200. PMID 15623502.

- ^ a b c d e f Ito, Yoshiaki (2012). "A Systems Approach and Skeletal Myogenesis". International Journal of Genomics. 2012. Hindawi Publishing Organization: 1–7. doi:10.1155/2012/759407. PMC 3443578. PMID 22991503.

- ^ Windner SE, Doris RA, Ferguson CM, Nelson AC, Valentin G, Tan H, Oates AC, Wardle FC, Devoto SH (2015). "Tbx6, Mesp-b and Ripply1 regulate the onset of skeletal myogenesis in zebrafish". Development. 142 (6) dev.113431: 1159–68. doi:10.1242/dev.113431. PMC 4360180. PMID 25725067.

- ^ Maroto, M; Reshef R; Münsterberg A E; Koester S; Goulding M; Lassar A B. (4 Apr 1997). "Ectopic Pax-3 activates MyoD and Myf-5 expression in embryonic mesoderm and neural tissue". Cell. 89 (1): 139–148. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80190-7. PMID 9094722.

- ^ Mathew, Sam J.; Hansen JM; Merrell AJ; Murphy MM; Lawson JA; Hutcheson DA; Hansen MS; Angus-Hill M; Kardon G (15 January 2011). "Connective tissue fibroblasts and Tcf4 regulate myogenesis". Development. 138 (2): 371–384. doi:10.1242/dev.057463. PMC 3005608. PMID 21177349.

- ^ Baylies, Mary (2001). "Invertebrate Myogenesis: looking back to the future of muscle development". Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 66 (4): 1281–6. doi:10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00214-8. PMID 11448630.

- ^ Laclef, Christine; Hamard G; Demignon J; Souil E; Houbron C; Maire P (14 February 2003). "Altered myogenesis in Six1-deficient mice". Development. 130 (10): 2239–2252. doi:10.1242/dev.00440. PMID 12668636.

- ^ Mansat, Mélanie; Kpotor, Afi Oportune; Chicanne, Gaëtan; et al. (2024-06-04). "MTM1-mediated production of phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphate fuels the formation of podosome-like protrusions regulating myoblast fusion". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 121 (23) e2217971121. doi:10.1073/pnas.2217971121. PMC 11161799. PMID 38805272.

- ^ Havis, Emmanuelle; Pascal Coumailleau; Aline Bonnet; Keren Bismuth; Marie-Ange Bonnin; Randy Johnson; Chen-Min Fan; Frédéric Relaix; De-Li Shi; Delphine Duprez (2012-03-16). "Development and Stem Cells". Development. 139 (7): 1910–1920. doi:10.1242/dev.072561. PMC 3347684. PMID 22513369.

- ^ Rios, Anne; Serralbo, Olivier; Salgado, David; Marcelle, Christophe (2011-06-15). "Neural crest regulates myogenesis through the transient activation of NOTCH". Nature. 473 (7348): 532–535. Bibcode:2011Natur.473..532R. doi:10.1038/nature09970. PMID 21572437. S2CID 4380479.

- ^ Bland, C.S; Wang, David; Johnson, Castle; Burge, Cooper (July 2010). "Global regulation of alternative splicing during myogenic differentiation". Nucleic Acids Research. 38 (21): 7651–7664. doi:10.1093/nar/gkq614. hdl:1721.1/66688. PMC 2995044. PMID 20634200.