Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

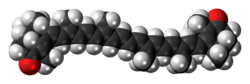

Canthaxanthin

View on Wikipedia | |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

β,β-Carotene-4,4′-dione

| |

| Systematic IUPAC name

3,3′-[(1E,3E,5E,7E,9E,11E,13E,15E,17E)-3,7,12,16-Tetramethyloctadeca-1,3,5,7,9,11,13,15,17-nonaene-1,18-diyl]bis(2,4,4-trimethylcyclohex-2-en-1-one) | |

Other names

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.007.444 |

| E number | E161g (colours) |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C40H52O2 | |

| Molar mass | 564.82 g/mol |

| Appearance | Violet crystals |

| Melting point | 211 to 212 °C (412 to 414 °F; 484 to 485 K) (decomposition)[2] |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Canthaxanthin /ˌkænθəˈzænθɪn/ ⓘ is a keto-carotenoid[3] pigment widely distributed in nature. Carotenoids belong to a larger class of phytochemicals known as terpenoids. The chemical formula of canthaxanthin is C40H52O2.[4] It was first isolated in edible mushrooms. It has also been found in green algae, bacteria, crustaceans, and bioaccumulates in fish such as carp, golden grey mullet, seabream and trush wrasse.[4]

Canthaxanthin is associated with E number E161g and is approved for use as a food coloring agent in different countries, including the United States[5] and the EU;[6] however, it is not approved for use in Australia and New Zealand.[7] It is generally authorized for feed applications in at least the following countries: US,[8] Canada,[9] EU.[10] In the EU, canthaxanthin is allowed by law to be added to trout feed, salmon feed and poultry feed.[11] The European Union limit is 80 mg/kg of feedstuffs,[4] 8 mg/kg in feed for egg laying hens and 25 mg/kg in feed for other poultry and salmonids.

Canthaxanthin is a potent lipid-soluble antioxidant.[12][13] The biological functions of canthaxanthin are related, at least in part, to its ability to function as an antioxidant (free radical scavenging/vitamin E sparing) in animal tissues.[14]

Biosynthesis

[edit]Due to the commercial value of carotenoids, their biosynthesis has been studied extensively in both natural producers, and non-natural (heterologous) systems such as the bacteria Escherichia coli and yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Canthaxanthin biosynthesis proceeds from beta-carotene via the action of a single protein, known as a beta-carotene ketolase, that is able to add a carbonyl group to carbon 4 and 4' of the beta carotene molecule. Although functionally identical, several distinct beta-carotene ketolase proteins are known. That is to say they differ from an evolutionary perspective in their primary amino acid/protein sequence. They are different proteins that complete the same function. Thus, bacterial (CrtW) and micro-algal beta-carotene ketolase proteins such as BKT isolated from Haematococcus pluvialis[15] are known. Due to the nature of canthaxanthin, relative to astaxanthin (a carotenoid of significant commercial value) these beta-carotene ketolase proteins have been studied extensively.[16][17] An E. coli based production system has been developed, that achieved canthanaxanthin production at 170 mg/L in lab scale fermentation.[18]

Presence in fish

[edit]Canthaxanthin is not found in wild Atlantic Salmon, but is a minor carotenoid in Pacific Salmon.[4] Canthaxanthin is used in farm-raised trout.[4] Canthaxanthin is used in combination with astaxanthin for some salmon feeds.[4]

Presence in birds

[edit]The antioxidant characteristics of canthaxanthin have been studied by a number of authors and experiments have shown that the presence of canthaxanthin can potentially help to reduce oxidation in a number of tissues including broiler meat and the chick embryo. In the egg, canthaxanthin is transferred from yolk to the developing embryo where it might help to protect the developing bird against oxidative damage, particularly during the sensitive periods of hatching and early posthatch life.[12][13] Flamingos are known to produce crop milk containing canthaxanthin for this purpose.

Effects on human pigmentation and health

[edit]When ingested for the purpose of simulating a tan, its deposition in the panniculus imparts a golden orange hue to the skin.[19]: 860

In the late 1980s, the safety of canthaxanthin as a feed and a food additive was drawn into question as a result of a completely un-related use of the same carotenoid. A reversible deposition of canthaxanthin crystals was discovered in the retina of a limited number of people who had consumed very high amounts of canthaxanthin via sun-tanning pills – after stopping the pills, the deposits disappeared and the health of those people affected was fully recovered. However, the level of canthaxanthin intake in the affected individuals was many times greater than that which could ever be consumed via poultry products - to reach a similar intake, an individual would have to consume more than 50 eggs per day, produced by hens fed practical levels of canthaxanthin in their diets. Moreover, it was demonstrated by Hueber et all. that ingestions of canthaxanthin cause no long-term adverse effects, and that the phenomenon of crystal deposition on the retina is reversible and does not result in morphological changes.[20][21] Although this incidence was totally unrelated and very different from the feed or food use of canthaxanthin, as a link had been drawn between canthaxanthin and human health, it was important that the use of canthaxanthin as a feed and food additive should be reviewed in detail by the relevant authorities, both in the EU and at an international level. The first stage of this review process was completed in 1995 with the publication by Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) of an Acceptable Daily Intake (ADI) for canthaxanthin of 0.03 mg/kg bodyweight. The work of JECFA was subsequently reviewed and accepted within the EU by the SCF (EU Scientific Committee for Food) in 1997. The conclusion of both these committees was that canthaxanthin is safe for humans. Recently (2010), the EFSA Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient sources added to food (ANS) published a revised version of the safety assessment of Canthaxanthin, reconfirming the already set ADI. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has no "tanning pills" approved for sale in the United States. In spite of this, there are companies that continue to market such products, some of which contain canthaxanthin. The FDA considers such items "adulterated cosmetics" and as a result sent warning letters to the firms citing such products as containing "a color additive that is unsafe within the meaning of section 721(a) of the FD&C Act (FD&C Act, sec. 601(e))."[22]

According to the FDA,[23]

Tanning pills have been associated with health problems, including an eye disorder called canthaxanthin retinopathy, which is the formation of yellow deposits on the eye's retina. Canthaxanthin has also been reported to cause liver injury and a severe itching condition called urticaria, according to the AAD.

References

[edit]- ^ Merck Index, 11th Edition, 1756.

- ^ Petracek, F. J.; Zechmeister, L. (1956). "Reaction of beta-carotene with N-bromosuccinimide: the formation and conversions of some polyene ketones". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 78 (7): 1427–1434. Bibcode:1956JAChS..78.1427P. doi:10.1021/ja01588a044.

- ^ Efficient Syntheses of the Keto-carotenoids Canthaxanthin, Astaxanthin, and Astacene. Seyoung Choi and Sangho Koo, J. Org. Chem., 2005, 70 (8), pages 3328–3331, doi:10.1021/jo050101l

- ^ a b c d e f Opinion on the use of canthaxanthin in feedingstuffs for salmon ...

- ^ "Colour Additive Status List". Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 2011-10-27.

- ^ "Current EU approved additives and their E Numbers". Food Standards Agency. 14 March 2012. Retrieved Dec 19, 2012.

- ^ "Standard 1.2.4 - Labelling of ingredients". Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code. 8 September 2011. Retrieved 2011-10-27.

- ^ "Code of Federal Regulations Title 21, 1 April 2012". Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 2013-06-21.

- ^ "Feeds Regulations, 1983 (SOR/83-593)". Justice Laws, Canada. Archived from the original on 2013-06-28. Retrieved 2013-06-21.

- ^ "European Union Register of Feed Additives, Revision 162 released 7 June 2013" (PDF). European Commission. Retrieved 2013-06-21.

- ^ Food Standards Agency UK (12 April 2010). "Canthaxanthin - your questions answered". Archived from the original on 23 March 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- ^ a b Surai, P.F. (2012). "The Antioxidant Properties of Canthaxanthin and Its Potential Effects in the Poultry Eggs and on Embryonic Development of the Chick, Part 1". World's Poultry Science Journal. 68 (3): 465–476. doi:10.1017/S0043933912000578. S2CID 92297763.

- ^ a b Surai, P.F. (2012). "The Antioxidant Properties of Canthaxanthin and Its Potential Effects in the Poultry Eggs and on Embryonic Development of the Chick, Part 2". World's Poultry Science Journal. 68 (4): 717–726. doi:10.1017/S0043933912000840. S2CID 86113041.

- ^ Surai, A.P.; Surai, P.F.; Steinberg, W.; Wakeman, W.G.; Speake, B.K.; Sparks, N.H.C. (2003). "Effect of canthaxanthin content of the maternal diet on the antioxidant system of the developing chick". British Poultry Science. 44 (4): 612–619. doi:10.1080/00071660310001616200. PMID 14584852. S2CID 42795189.

- ^ Lotan, T; Hirschberg, J (May 8, 1995). "Cloning and expression in Escherichia coli of the gene encoding beta-C-4-oxygenase, that converts beta-carotene to the ketocarotenoid canthaxanthin in Haematococcus pluvialis". FEBS Letters. 364 (2): 125–8. Bibcode:1995FEBSL.364..125L. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(95)00368-J. PMID 7750556. S2CID 25187964.

- ^ Scaife, M.A.; Burja, A.M.; Wright, P.C. (1 August 2009). "Characterization of cyanobacterial beta-carotene ketolase and hydroxylase genes in Escherichia coli, and their application for astaxanthin biosynthesis". Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 103 (5): 944–55. Bibcode:2009BiotB.103..944S. doi:10.1002/bit.22330. PMID 19365869. S2CID 10425589.

- ^ Fraser, P.D.; Miura, Y.; Misawa, N. (7 March 1997). "In vitro characterization of astaxanthin biosynthetic enzymes". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 272 (10): 6128–35. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.10.6128. PMID 9045623.

- ^ Scaife, Mark A.; Ma, Cynthia A.; Norman, Andrew; Armenta, Roberto E. (1 October 2012). "Progress toward an Escherichia coli canthaxanthin bioprocess". Process Biochemistry. 47 (12): 2500–2509. doi:10.1016/j.procbio.2012.10.012.

- ^ James, William; Berger, Timothy; Elston, Dirk (2005). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. (10th ed.). Saunders. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0.

- ^ "Sun less Tanning". Monday, 26 August 2019

- ^ Hueber, A.; Rosentreter, A.; Severin, M. (2011). "Canthaxanthin Retinopathy: Long-Term Observations". Ophthalmic Research. 46 (2): 103–106. doi:10.1159/000323813. PMID 21346389. S2CID 7495247.

- ^ "Warning Letters Cite Cosmetics as Adulterated Due to Violative Use of the Color Additive Canthaxanthin". April 5, 2005. Archived from the original on May 28, 2009. Retrieved May 13, 2012.

- ^ "Sun Safety: Protect the Skin You're In!". FDA & You, Issue #3. Food and Drug Administration. Spring–Summer 2003. Archived from the original on January 19, 2009.