Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Fisetin

View on Wikipedia

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

3,3′,4′,7-Tetrahydroxyflavone

| |

| Systematic IUPAC name

2-(3,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)-3,7-dihydroxy-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one | |

| Other names

2-(3,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)-3,7-dihydroxychromen-4-one

Cotinin (not to be confused with Cotinine) 5-Deoxyquercetin Superfustel Fisetholz Fietin Fustel Fustet Viset Junger fustik | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.007.669 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C15H10O6 | |

| Molar mass | 286.2363 g/mol |

| Density | 1.688 g/mL |

| Melting point | 330 °C (626 °F; 603 K) |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Fisetin (7,3′,4′-flavon-3-ol) is a plant flavonol from the flavonoid group of polyphenols.[1] It occurs in many plants where it serves as a yellow pigment. It is found in many fruits and vegetables, such as strawberries, apples, persimmons, onions, and cucumbers.[2][3][4]

Its chemical formula was first described by Austrian chemist Josef Herzig in 1891.[5]

Sources

[edit]Fisetin is a flavonoid synthesized by many plants such as the trees and shrubs of Fabaceae, acacias Acacia greggii,[6] and Acacia berlandieri,[6] parrot tree (Butea frondosa), honey locust (Gleditsia triacanthos), members of the family Anacardiaceae such as the Quebracho colorado, and species of the genus Rhus, which contains the sumacs.[7] Along with myricetin, fisetin provides the color of the traditional yellow dye young fustic, an extract from the Eurasian smoketree (Rhus cotinus).

Many fruits and vegetables contain fisetin.[2] In one study, fisetin content was highest in strawberries, with content also observed in apples, grapes, onions, tomatoes, and cucumbers.[2] Fisetin can be extracted from fruit juices, wines,[8] and teas.[3] It is also present in Pinophyta species such as the yellow cypress (Callitropsis nootkatensis).

The average intake of fisetin from foods in Japan is about 0.4 mg per day.[1]

| Plant source | Amount of fisetin (μg/g) |

|---|---|

| Toxicodendron vernicifluum[9] | 15000 |

| Strawberry[2] | 160 |

| Apple[2] | 26 |

| Persimmon[2] | 10.6 |

| Onion[2] | 4.8 |

| Lotus root[2] | 5.8 |

| Grape[2] | 3.9 |

| Kiwifruit[2] | 2.0 |

| Peach[2] | 0.6 |

| Cucumber[2] | 0.1 |

| Tomato[2] | 0.1 |

Research

[edit]Although fisetin has been under laboratory research over several decades for its potential role in senescence or anticancer properties, among other possible effects, there is no clinical evidence that it provides any benefit to human health, as of 2018.[1]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Yousefzadeh MJ, Zhu Y, McGowan SJ, et al. (1 October 2018). "Fisetin is a senotherapeutic that extends health and lifespan". eBioMedicine. 36: 18–28. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.09.015. ISSN 2352-3964. PMC 6197652. PMID 30279143.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Arai Y, Watanabe S, Kimira M, et al. (2000). "Dietary intakes of flavonols, flavones and isoflavones by Japanese women and the inverse correlation between quercetin intake and plasma LDL cholesterol concentration". The Journal of Nutrition. 130 (9): 2243–2250. doi:10.1093/jn/130.9.2243. PMID 10958819.

- ^ a b Viñas P, Martínez-Castillo N, Campillo N, et al. (2011). "Directly suspended droplet microextraction with in injection-port derivatization coupled to gas chromatography–mass spectrometry for the analysis of polyphenols in herbal infusions, fruits and functional foods". Journal of Chromatography A. 1218 (5): 639–646. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2010.12.026. PMID 21185565.

- ^ Fiorani M, Accorsi A (2005). "Dietary flavonoids as intracellular substrates for an erythrocyte trans-plasma membrane oxidoreductase activity". The British Journal of Nutrition. 94 (3): 338–345. doi:10.1079/bjn20051504. PMID 16176603.

- ^ Herzig J (1891). "Studien über Quercetin und seine Derivate, VII. Abhandlung" [Studies on Quercetin and its Derivatives, Treatise VII]. Monatshefte für Chemie (in German). 12 (1): 177–90. doi:10.1007/BF01538594. S2CID 197766725.

- ^ a b Forbes TDA, Clement BA. "Chemistry of Acacia's from South Texas" (PDF). Texas A&M Agricultural Research and Extension Center at. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 May 2011. Retrieved 14 April 2010.

- ^ Gábor M, Eperjessy E (1966). "Antibacterial Effect of Fisetin and Fisetinidin". Nature. 212 (5067): 1273. Bibcode:1966Natur.212.1273G. doi:10.1038/2121273a0. PMID 21090477. S2CID 4262402.

- ^ De Santi C, Pietrabissa A, Mosca F, et al. (2002). "Methylation of quercetin and fisetin, flavonoids widely distributed in edible vegetables, fruits and wine, by human liver". International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 40 (5): 207–212. doi:10.5414/cpp40207. PMID 12051572.

- ^ Lee SO, Kim SJ, Kim JS, et al. (2 June 2021). "Comparison of the main components and bioactivity of Rhus verniciflua Stokes extracts by different detoxification processing methods". BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 18 (1): 242. doi:10.1186/s12906-018-2310-x. PMC 6118002. PMID 30165848.

Fisetin

View on GrokipediaChemical properties

Molecular structure

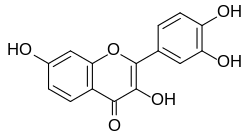

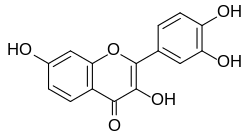

Fisetin is a naturally occurring flavonol with the molecular formula and a molecular weight of 286.24 g/mol.[1] Its systematic IUPAC name is 2-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-3,7-dihydroxychromen-4-one, though it is commonly referred to as 3,3',4',7-tetrahydroxyflavone in scientific literature.[8] This nomenclature reflects its classification within the flavonoid family, specifically the flavonol subclass, which features a 3-hydroxyflavone core structure.[12] The core structure of fisetin consists of two aromatic rings—an A-ring (a benzene ring fused to a heterocyclic pyrone) and a B-ring (a phenyl substituent)—linked by a central γ-pyrone ring (C-ring). This tricyclic system is characterized by extensive π-conjugation, contributing to its stability and bioactive properties. Hydroxyl groups are positioned at the 3-position on the C-ring, the 7-position on the A-ring, and the 3' and 4' positions on the B-ring, with the 4-position of the C-ring bearing a carbonyl group. These functional groups, particularly the ortho-dihydroxy configuration on the B-ring, are key to its chemical reactivity and biological interactions.[13][14] In comparison to the related flavonol quercetin (3,5,7,3',4'-pentahydroxyflavone), fisetin lacks a hydroxyl group at the 5-position of the A-ring, earning it the synonym 5-deoxyquercetin; this structural difference influences its solubility, redox potential, and interactions with biological targets.[1] The absence of chiral centers in fisetin results in no stereoisomers, and its planar geometry arises from the delocalized electron system across the conjugated rings, facilitating stacking interactions in molecular assemblies.[1][15]Physical characteristics

Fisetin is typically observed as a yellowish to orange crystalline powder.[16] Its melting point is approximately 330–333 °C, at which point it decomposes.[17] Fisetin exhibits poor solubility in water (≈0.3 mg/mL at 25 °C) but is soluble in organic solvents such as ethanol (≈5 mg/mL), DMSO (≈30 mg/mL), and DMF (≈30 mg/mL), as well as in alkaline solutions; its logP value of ≈2.3 reflects moderate lipophilicity.[1][18] The compound is sensitive to light and oxidation, remaining stable under acidic conditions but degrading in strong basic environments.[19] Spectroscopically, fisetin displays UV-Vis absorption maxima at 254 nm and 368 nm, with characteristic IR absorption bands and NMR signals attributable to its flavonoid backbone, including aromatic protons and hydroxyl groups.[1]History and occurrence

Discovery and isolation

Fisetin was first isolated in 1833 from the smoke tree (Rhus cotinus L.), also known as Venetian sumac, a plant historically valued for its pigment properties.[11] This extraction marked one of the earliest isolations of a flavonoid compound, highlighting the compound's role in plant coloration and traditional applications.[17] The chemical formula of fisetin was determined in 1891 by Austrian chemist Josef Herzig, who provided a foundational description of its structure as 3,3',4',7-tetrahydroxyflavone.[20] Herzig's work built on initial characterizations and contributed to the emerging understanding of flavonols within plant chemistry. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, fisetin was investigated as part of broader studies on flavonoid pigments responsible for yellow hues in various plants, reflecting its natural occurrence in species like those in the Rhus genus.[21] Fisetin was recognized early on for its use as a dye in traditional practices, derived from the wood and bark of the smoke tree to produce yellow and ochre tones in textiles and other materials.[22] Key advancements in the early 1900s included the first chemical synthesis of fisetin around 1904, which involved cyclization of protected chalcones, enabling improved purification and crystallization techniques for more precise analysis.[23] These methods facilitated its separation from complex plant extracts and supported ongoing research into its properties as a pigment and chemical entity.[24]Natural sources

Fisetin is a flavonoid found in various plant families, including Fabaceae (such as acacias like Acacia greggii and Acacia berlandieri), Moraceae (such as mulberry, Morus species), and Anacardiaceae (such as smoke tree, Cotinus coggygria, and wax tree, Rhus succedanea).[6][25][26] Among dietary sources, fisetin occurs at varying concentrations in fruits and vegetables, with strawberries containing the highest levels at approximately 160 μg/g, followed by apples at 26.9 μg/g and persimmons at 10.5 μg/g. Onions provide about 4.8 μg/g, grapes around 3.9 μg/g, and cucumbers roughly 0.1 μg/g, while tomatoes and other vegetables like kale also contribute smaller amounts. The following table summarizes representative fisetin concentrations in select high-content foods:| Food | Fisetin Concentration (μg/g) |

|---|---|

| Strawberries | 160 |

| Apples | 26.9 |

| Persimmons | 10.5 |

| Onions | 4.8 |

| Grapes | 3.9 |

| Cucumbers | 0.1 |