Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Flint River

View on Wikipedia

| Flint River | |

|---|---|

Jim Woodruff Dam, at the mouth of the Flint River | |

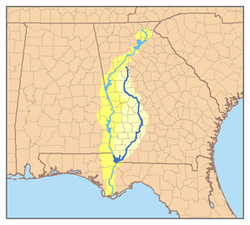

Map of the Apalachicola River system with the Flint River in dark blue and its watershed highlighted. | |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Flint River |

| • location | College Park, Georgia |

| • coordinates | 33°40′08″N 84°26′24″W / 33.669°N 84.440°W |

| • elevation | 1,027 ft (313 m) |

| Mouth | Apalachicola River |

• location | Lake Seminole |

• coordinates | 30°43′44″N 84°52′30″W / 30.729°N 84.875°W |

• elevation | 77 ft (23 m) |

| Length | 344 mi (554 km) |

| Basin size | 8,460 sq mi (21,900 km2) |

The Flint River is a 344-mile-long (554 km)[1] river in the U.S. state of Georgia. The river drains 8,460 square miles (21,900 km2) of western Georgia, flowing south from the upper Piedmont region south of Atlanta to the wetlands of the Gulf Coastal Plain in the southwestern corner of the state. Along with the Apalachicola and the Chattahoochee rivers, it forms part of the ACF basin. In its upper course through the red hills of the Piedmont, it is considered especially scenic, flowing unimpeded for over 200 miles (320 km). Historically, it was also called the Thronateeska River.[2]

Description

[edit]The Flint River rises in west central Georgia in the city of East Point in southern Fulton County on the southern outskirts of the Atlanta metropolitan area as ground seepage. The exact start can be traced to the field located between Plant Street, Willingham Drive, Elm Street, and Vesta Avenue. It travels under the runways of the Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport.[3] Flowing generally south through rural western Georgia, the river is fed by Line Creek, and Whitewater Creek in Fayette County. The river passes through Sprewell Bluff State Park, approximately 10 miles (16 km) west of Thomaston. Farther south, it comes within 5 miles (8 km) of Andersonville, the site of the Andersonville prison during the Civil War.

In southwestern Georgia, the river flows through downtown Albany, the largest city on the river. At Bainbridge it joins Lake Seminole, formed at its confluence with the Chattahoochee River upstream from the Jim Woodruff Dam, very near the Florida state line. From this confluence, the Apalachicola River flows south from the reservoir through Florida to the Gulf of Mexico.

The Flint River is fed by Kinchafoonee Creek just north of Albany, and by Ichawaynochaway Creek in southwestern Mitchell County, approximately 15 miles (24 km) northeast of Bainbridge.

In addition to Lake Seminole, the Flint River is impounded approximately 15 miles (24 km) upstream from Albany to form the Lake Blackshear reservoir.

The Flint River is one of only 40 rivers in the nation to flow more than 200 miles (320 km) unimpeded by dams or other manmade systems, and is increasingly valued for that. In the 1970s, a plan by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to build a dam at Sprewell Bluff in Upson County was defeated by Jimmy Carter, then the Governor of Georgia, and other supporters. Carter's hometown of Plains is located near the Flint River.

Natural history

[edit]The river is considered to have three distinct sections as it flows southward through western Georgia. In its upper reaches in the red hills of the Piedmont, it flows through a deeply incised channel etched into crystalline rocks. South of its fall line near Culloden, the channel transforms to a broad, forested swampy flood plain. South of Lake Blackshear, it transforms again, flowing through a channel in limestone rock above the Upper Floridan Aquifer below southwestern Georgia and northwestern Florida [citation needed].

The river has been prone to floods throughout its history. In 1994, during flooding from Tropical Storm Alberto, the river crested at 43 feet (13 m) in Albany, resulting in the emergency evacuation of over 23,000 residents. It caused one of the worst natural disasters in the state's history. Interstate 75 was closed in Macon, and Albany State University was also seriously flooded, as the river became a few miles or several kilometers wide in some places. The water lifted caskets from cemeteries and left them, along with drowned cattle and other livestock, stuck in trees and other places.

Montezuma, Georgia was completely inundated after the Flint River topped the 29-foot levee protecting the town from floodwater. The official depth of the river at the height of the flood was estimated at 34 feet. The nearby gauge was underwater, making it impossible to get an accurate reading. Cleanup and restoration of Albany took months to complete. In 1998 another serious flood occurred in Albany, but it was not as damaging as the one of 1994.[4] Bainbridge also flooded in 1998. Other significant floods occurred in 1841 and 1925.

In January 2002, a winter storm blew through Atlanta the day after New Year's Day. The airport's drainage system overflowed, resulting in deicing fluid leaking into the river. Although the antifreeze entered the drinking water of some residents, no one became seriously ill. The airport changed its drainage system to prevent the problem in the future. No problems were reported after an unusually heavy 4 inches (10 cm) of rain officially fell at the airport at the beginning of March 2009.

In May 2009, the National Fish Habitat Action Plan named the Lower Flint River one of its "10 Waters to Watch" for 2009 for its habitat restoration work. In October 2009, American Rivers placed the Flint on its list of America's Most Endangered Rivers, mainly due to new plans to put a dam on it.[5]

The Flint is one of four rivers in the southeast with significant remaining populations of Hymenocallis coronaria, the Shoals spider-lily. Four separate stands of the plant have been studied and documented in the river, ranging from Yellow Jacket Shoals to Hightower Shoals.[6]

In popular culture

[edit]In Gone With the Wind, author Margaret Mitchell describes the Flint River as bordering the fictional plantation Tara.

American country music singer Luke Bryan, a native of Georgia, references the river in his songs "That's My Kind of Night"; "Huntin', Fishin' & Lovin' Every Day"; and "We Rode in Trucks".

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline data. The National Map Archived 2012-03-29 at the Wayback Machine, accessed April 15, 2011

- ^ Thronateeska chapter, Daughters of the American revolution (1924). History and reminiscences of Dougherty county, Georgia. Albany, Georgia: Herald publishing company. p. 16.

- ^ Flint River Archived 2012-09-30 at the Wayback Machine article at the New Georgia Encyclopedia

- ^ "Rain pounds Georgia again, raising flood concerns". USA Today. 2005-04-03.

- ^ Flint River, one of America's Most Endangered Rivers of 2009, still faces critical threats, americanrivers.org American Rivers, archived from the original on December 5, 2010, retrieved February 8, 2010

- ^ Markwith, Scott H.; Scanlon, Michael J. (May 11, 2006). "Multiscale analysis of Hymenocallis coronaria (Amaryllidaceae) genetic diversity, genetic structure, and gene movement under the influence of unidirectional stream flow". American Journal of Botany. Botanical Society of America. Archived from the original on December 20, 2012. Retrieved October 1, 2012.

External links

[edit]Flint River

View on GrokipediaPhysical Geography

Course and Length

The Flint River originates as groundwater seepage emerging from a concrete culvert on Virginia Avenue in Hapeville, a suburb of Atlanta in Clayton County, Georgia, just south of Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport.[1] This unusual headwater source marks the beginning of its southward trajectory through west-central Georgia, initially traversing urban and suburban landscapes before entering more rural Piedmont terrain.[1][9] The river flows generally south for approximately 344 miles (554 km), draining 8,460 square miles (21,900 km²) entirely within Georgia's borders.[10] It crosses the fall line near Culloden, where it descends about 400 feet over roughly 50 miles into the Coastal Plain, transitioning from rocky shoals to sandy bottoms and meandering channels.[1] Key cities and towns along its course include Jonesboro, Griffin, Thomaston, Montezuma, Marshallville, Cordele, Americus, Albany, and Bainbridge; the river passes through two reservoirs formed by dams—Lake Blackshear (near Cordele, impounded by the Crisp County Dam) and Lake Chelaw (near Albany, impounded by the Chelaw Dam)—which generate hydroelectric power but leave much of the river free-flowing.[1][2] Near the Florida state line, approximately 265 miles downstream from its headwaters, the Flint River joins the Chattahoochee River at the Jim Woodruff Lock and Dam, forming Lake Seminole and contributing to the Apalachicola River system that empties into the Gulf of Mexico.[1] This confluence supports navigation and flood control in the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint basin, managed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.[11] The river's meandering path results in a channel length exceeding straight-line distance estimates, with over 220 miles remaining unimpeded by major dams, one of the longest such stretches in the contiguous United States.[2][12]Tributaries and Basin

The Flint River drainage basin covers approximately 8,460 square miles (21,900 km²) entirely within Georgia, encompassing parts of 52 counties primarily in the southwestern region of the state.[3] This area spans from urban headwaters near metropolitan Atlanta southward through the Piedmont, Fall Line Hills, and Dougherty Plain physiographic provinces to the Gulf Coastal Plain, where the river meets the Chattahoochee River at Lake Seminole on the Florida border.[13] The basin's hydrology is influenced by karst features in the lower reaches, with significant groundwater contributions from aquifers underlying the region.[14] Major tributaries augment the Flint's flow, with contributions varying by sub-basin. In the upper Flint River basin, key streams include Line Creek, Morning Creek, White Oak Creek, and Whitewater Creek, draining urban and suburban areas in counties such as Fayette, Clayton, Coweta, Douglas, and Henry.[15] Further downstream in the middle and lower basin, prominent tributaries are Kinchafoonee Creek, Muckalee Creek, Ichawaynochaway Creek, Chickasawhatchee Creek, and Spring Creek, which originate as springs and seeps in the karst terrain and support extensive agricultural irrigation.[16] Spring Creek, draining 585 square miles (1,515 km²), exemplifies the basin's groundwater-dependent systems, discharging directly into Lake Seminole rather than the mainstem Flint due to reservoir impoundment.[14] The basin's sub-watersheds, delineated by the U.S. Geological Survey's Hydrologic Unit Code system, include the Upper Flint, Middle Flint, Lower Flint, Kinchafoonee-Muckalee Creeks, Ichawaynochaway Creek, and Spring Creek units, each exhibiting distinct flow regimes influenced by local geology and land use dominated by agriculture in the lower portions.[17] Wetlands cover an estimated 412,000 acres within the basin, comprising about 5% of the total area and playing a critical role in water retention and filtration.[2]Hydrology and Flow Characteristics

The Flint River displays a highly variable flow regime typical of southeastern U.S. rivers in the Piedmont and Coastal Plain physiographic provinces, where precipitation drives rapid responses in discharge with limited natural storage. Mean annual discharge increases progressively downstream due to tributary contributions and, in the lower basin, substantial groundwater inflows from the karstic Floridan aquifer system, which sustains baseflows during dry periods. At the upper basin gauge near Griffin (USGS 02344500), long-term mean discharge is 335.5 cubic feet per second (cfs), reflecting a small drainage area of approximately 550 square miles and flashy responses to localized storms.[15] Mid-basin at Montezuma (USGS 02349500), mean discharge rises to 4,492 cfs over the period of record, with annual means ranging from a low of 1,752 cfs in 1988 to a high of 5,593 cfs in 1975, and peak daily flows reaching 53,600 cfs on March 11 during a major flood event.[18] Near the mouth at Bainbridge (USGS 02356000), average streamflow approximates 14,124 cfs across the full 8,460-square-mile basin, though interannual variability remains pronounced due to climatic cycles.[19][3] Seasonal flow patterns follow regional rainfall distribution, with peak discharges typically occurring in winter and early spring (December–March) from frequent frontal systems and occasional tropical remnants, while late summer and fall (July–October) see minima driven by evapotranspiration and sparse precipitation. Baseflows, which constitute a larger proportion of total flow in the lower Flint due to aquifer recharge through sinkholes and losing streams upstream, exhibit less extreme diurnal fluctuations than surface runoff-dominated upper reaches but are vulnerable to prolonged dry spells.[20] Human factors amplify low-flow conditions: agricultural irrigation withdrawals in the lower basin, permitted at levels exceeding 200% of minimum flows and 30% of mean flows, contribute to reduced baseflows, particularly post-1975 amid intensified pumping from the aquifer.[16][20] Conversely, floods from intense rainfall events can produce rapid rises; for instance, extreme droughts like 2007–2010 caused dewatering of upper reaches (flows below 100 cfs for extended periods at gauges like Carsonville), while the lower basin relied on groundwater to avoid complete cessation.[21] The river's largely free-flowing nature—unimpounded for over 200 miles—preserves natural hydrograph shapes, including quick recession limbs after peaks, but downstream regulation at Jim Woodruff Lock and Dam (at the Flint-Apalachicola confluence) alters tailwater influences on the terminal reach. Flow duration analyses indicate high variability coefficients, with daily records showing sensitivity to watershed area scaling; smaller subbasins exhibit greater relative fluctuations (e.g., coefficient of variation >1.0) than the integrated mainstem.[22] Climate variability, including El Niño–Southern Oscillation cycles, modulates baseflow recessions, with multi-year droughts reducing median flows by up to 50% in affected periods.[23]| Gauge Location | USGS ID | Drainage Area (sq mi) | Mean Discharge (cfs) | Max Daily Discharge (cfs) | Min Annual Mean (cfs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Near Griffin | 02344500 | ~550 | 335.5 | 2,644 | 6.01 |

| At Montezuma | 02349500 | ~4,200 | 4,492 | 53,600 (Mar 11) | 1,752 (1988) |

| At Bainbridge | 02356000 | 8,460 | ~14,124 | N/A | N/A |