Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Darter

View on Wikipedia| Darter Temporal range: Early Miocene – Recent

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Male African darter Anhinga rufa | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Suliformes |

| Family: | Anhingidae Reichenbach, 1849[1] |

| Genus: | Anhinga Lacépède, 1799 |

| Type species | |

| Pelecanus anhinga Linnaeus, 1766

| |

| Species | |

|

Anhinga anhinga | |

| |

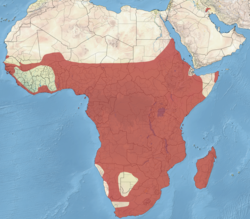

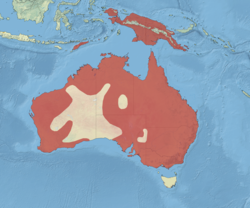

| World distribution of the family Anhingidae | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Family-level: Genus-level: | |

The darters, anhingas, or snakebirds are mainly tropical waterbirds in the family Anhingidae, which contains a single genus, Anhinga. There are four living species, three of which are very common and widespread while the fourth is rarer and classified as near-threatened by the IUCN. The term snakebird is usually used without any additions to signify whichever of the completely allopatric species occurs in any one region. It refers to their long thin neck, which has a snake-like appearance when they swim with their bodies submerged, or when mated pairs twist it during their bonding displays. "Darter" is used with a geographical term when referring to particular species. It alludes to their manner of procuring food, as they impale fishes with their thin, pointed beak. The American darter (A. anhinga) is more commonly known as the anhinga. It is sometimes called "water turkey" in the southern United States; though the anhinga is quite unrelated to the wild turkey, they are both large, blackish birds with long tails that are sometimes hunted for food.[2]

Description

[edit]

Anhingidae are large birds with sexually dimorphic plumage. They measure about 80 to 100 cm (2.6 to 3.3 ft) in length, with a wingspan around 120 cm (3.9 ft), and weigh some 1,050 to 1,350 grams (37 to 48 oz). The males have black and dark-brown plumage, a short erectile crest on the nape and a larger bill than the female. The females have much paler plumage, especially on the neck and underparts, and are a bit larger overall. Both have grey stippling on long scapulars and upper wing coverts. The sharply pointed bill has serrated edges, a desmognathous palate and no external nostrils. The darters have completely webbed feet, and their legs are short and set far back on the body.[3]

There is no eclipse plumage, but the bare parts vary in color around the year. During breeding, however, their small gular sac changes from pink or yellow to black, and the bare facial skin, otherwise yellow or yellow-green, turns turquoise. The iris changes in color between yellow, red or brown seasonally. The young hatch naked, but soon grow white or tan down.[4]

Darter vocalizations include a clicking or rattling when flying or perching. In the nesting colonies, adults communicate with croaks, grunts or rattles. During breeding, adults sometimes give a caw or sighing or hissing calls. Nestlings communicate with squealing or squawking calls.[4]

Distribution and ecology

[edit]

Darters are mostly tropical in distribution, ranging into subtropical and barely into warm temperate regions. They typically inhabit fresh water lakes, rivers, marshes, swamps, and are less often found along the seashore in brackish estuaries, bays, lagoons and mangrove. Most are sedentary and do not migrate; the populations in the coolest parts of the range may migrate however. Their preferred mode of flight is soaring and gliding; in flapping flight they are rather cumbersome. On dry land, darters walk with a high-stepped gait, wings often spread for balance, just like pelicans do. They tend to gather in flocks – sometimes up to about 100 birds – and frequently associate with storks, herons or ibises, but are highly territorial on the nest: despite being a colonial nester, breeding pairs – especially males – will stab at any other bird that ventures within reach of their long neck and bill. The Oriental darter (A. melanogaster sensu stricto) is a Near Threatened species. Habitat destruction along with other human interferences (such as egg collection and pesticide overuse) are the main reasons for declining darter populations.[2]

Diet

[edit]

Darters feed mainly on mid-sized fish;[5] far more rarely, they eat other aquatic vertebrates[6] and large invertebrates[7] of comparable size. These birds are foot-propelled divers which quietly stalk and ambush their prey; then they use their sharply pointed bill to impale the food animal. They do not dive deep but make use of their low buoyancy made possible by wettable plumage, small air sacs and denser bones.[8] On the underside of the cervical vertebrae 5–7 is a keel, which allows for muscles to attach to form a hinge-like mechanism that can project the neck, head and bill forward like a throwing spear. After they have stabbed the prey, they return to the surface where they toss their food into the air and catch it again, so that they can swallow it head-first. Like cormorants, they have a vestigial preen gland and their plumage gets wet during diving. To dry their feathers after diving, darters move to a safe location and spread their wings.[4] Darters go through a synchronous moult of all their primaries and secondaries making them temporarily flightless, although it is possible that some individuals go through incomplete moults.[9]

Predation

[edit]Predators of darters are mainly large carnivorous birds, including passerines like the Australian raven (Corvus coronoides) and house crow (Corvus splendens), and birds of prey such as marsh harriers (Circus aeruginosus complex) or Pallas's fish eagle (Haliaeetus leucoryphus). Predation by Crocodylus crocodiles has also been noted. But many would-be predators know better than to try to catch a darter. The long neck and pointed bill in combination with the "darting" mechanism make the birds dangerous even to larger carnivorous mammals, and they will actually move toward an intruder to attack rather than defending passively or fleeing.[10]

Breeding

[edit]They usually breed in colonies, occasionally mixed with cormorants or herons. The darters pair bond monogamously at least for a breeding season. There are many different types of displays used for mating. Males display to attract females by raising (but not stretching) their wings to wave them in an alternating fashion, bowing and snapping the bill, or giving twigs to potential mates. To strengthen the pair bond, partners rub their bills or wave, point upwards or bow their necks in unison. When one partner comes to relieve the other at the nest, males and females use the same display the male employs during courtship; during changeovers, the birds may also "yawn" at each other.[10]

Breeding is seasonal (peaking in March/April) at the northern end of their range; elsewhere they can be found breeding all year round. The nests are made of twigs and lined with leaves; they are built in trees or reeds, usually near water. Typically, the male gathers nesting material and brings it to the female, which does most of the actual construction work. Nest construction takes only a few days (about three at most), and the pairs copulate at the nest site. The clutch size is two to six eggs (usually about four) which have a pale green color. The eggs are laid within 24–48 hours and incubated for 25 to 30 days, starting after the first has been laid; they hatch asynchronously. To provide warmth to the eggs, the parents will cover them with their large webbed feet, because like their relatives they lack a brood patch. The last young to hatch will usually starve in years with little food available. Bi-parental care is given and the young are considered altricial. They are fed by regurgitation of partly digested food when young, switching to entire food items as they grow older. After fledging, the young are fed for about two more weeks while they learn to hunt for themselves.[11]

These birds reach sexual maturity by about two years, and generally live to around nine years. The maximum possible lifespan of darters seems to be about sixteen years.[12]

Darter eggs are edible and considered delicious by some; they are locally collected by humans as food. The adults are also eaten occasionally, as they are rather meaty birds (comparable to a domestic duck); like other fish-eating birds such as cormorants or seaducks they do not taste particularly good though. Darter eggs and nestlings are also collected in a few places to raise the young. Sometimes this is done for food, but some nomads in Assam and Bengal train tame darters to be employed as in cormorant fishing. With an increasing number of nomads settling down in recent decades, this cultural heritage is in danger of being lost. On the other hand, as evidenced by the etymology of "anhinga" detailed below, the Tupi seem to have considered the anhinga a kind of bird of ill omen.[4]

Systematics and evolution

[edit]

The genus Anhinga was introduced by the French zoologist Bernard Germain de Lacépède in 1799, with the anhinga or American darter (Anhinga anhinga) as the type species.[13][14] Anhinga is derived from the Tupi ajíŋa (also transcribed áyinga or ayingá), which in local mythology refers to a malevolent demonic forest spirit; it is often translated as "devil bird". The name changed to anhingá or anhangá as it was transferred to the Tupi–Portuguese Língua Geral. However, in its first documented use as an English term in 1818, it referred to an Old World darter. Ever since, it has also been used for the modern genus Anhinga as a whole.[15]

This family is very closely related to the other families in the suborder Sulae, i.e. the Phalacrocoracidae (cormorants and shags) and the Sulidae (gannets and boobies). Cormorants and darters are extremely similar as regards their body and leg skeletons and may be sister taxa. In fact, several darter fossils were initially believed to be cormorants or shags (see below). Some earlier authors included the darters in the Phalacrocoracidae family as a subfamily, Anhinginae, but this is nowadays generally considered overlumping. However, as this agrees quite well with the fossil evidence,[16] some unite the Anhingidae and Phalacrocoracidae in a superfamily Phalacrocoracoidea.[17]

The Sulae are also united by their characteristic display behavior, which agrees with the phylogeny as laid out by anatomical and DNA sequence data. While the darters' lack of many display behaviors is shared with gannets (and that of a few with cormorants), these are all symplesiomorphies that are absent in frigatebirds, tropicbirds and pelicans also. Like cormorants but unlike other birds, darters use their hyoid bone to stretch the gular sac in display. Whether the pointing display of mates is another synapomorphy of darters and cormorants that was dropped again in some of the latter, or whether it evolved independently in darters and those cormorants that do it, is not clear. The male raised-wing display seems to be a synapomorphy of the Sulae; like almost all cormorants and shags but unlike almost all gannets and boobies, darters keep their wrists bent as they lift the wings in display, but their alternating wing-waving, which they also show before take-off, is unique. That they often balance with their outstretched wings during walking is probably an autapomorphy of darters, necessitated by their being plumper than the other Sulae.[18]

The Sulae were traditionally included in the Pelecaniformes, then a paraphyletic group of "higher waterbirds". The supposed traits uniting them, like all-webbed toes and a bare gular sac, are now known to be convergent, and pelicans are apparently closer relatives of storks than of the Sulae. Hence, the Sulae and the frigatebirds – and some prehistoric relatives – are increasingly separated as the Suliformes, which is sometimes dubbed "Phalacrocoraciformes".[19]

Living species

[edit]There are four living species of darters recognized, all in the genus Anhinga,[20] although the Old World ones were often lumped together as subspecies of A. melanogaster. They may form a superspecies with regard to the more distinct anhinga:[21]

| Common name | Scientific name and subspecies | Range | Size and ecology | IUCN status and estimated population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anhinga or American darter | Anhinga anhinga (Linnaeus, 1766) Two subspecies

|

southern United States, Mexico, Cuba, and Grenada, Brazil.

|

Size: Habitat: Diet: |

LC

|

| Oriental darter | Anhinga melanogaster Pennant, 1769 |

tropical South Asia and Southeast Asia.

|

Size: Habitat: Diet: |

NT

|

| African darter | Anhinga rufa (Daudin, 1802) Two subspecies

|

sub-Saharan Africa and Iraq.

|

Size: Habitat: Diet: |

LC

|

| Australasian darter | Anhinga novaehollandiae Gould, 1847 |

Australia, Indonesia, and Papua New Guinea

|

Size: Habitat: Diet: |

LC

|

Extinct "darters" from Mauritius and Australia known only from bones were described as Anhinga nana ("Mauritian darter") and Anhinga parva. But these are actually misidentified bones of the long-tailed cormorant (Microcarbo/Phalacrocorax africanus) and the little pied cormorant (M./P. melanoleucos), respectively. In the former case, however, the remains are larger than those of the geographically closest extant population of long-tailed cormorants on Madagascar: they thus might belong to an extinct subspecies (Mauritian cormorant), which would have to be called Microcarbo africanus nanus (or Phalacrocorax a. nanus) – quite ironically, as the Latin term nanus means dwarf. The Late Pleistocene Anhinga laticeps is not specifically distinct from the Australasian darter; it might have been a large paleosubspecies of the last ice age.[22]

Fossil record

[edit]

The fossil record of the Anhingidae is rather dense, but very apomorphic already and appears to be lacking its base. The other families placed in the Phalacrocoraciformes sequentially appear throughout the Eocene, the most distinct – frigatebirds – being known since almost 50 Ma (million years ago) and probably of Paleocene origin. With fossil gannets being known since the mid-Eocene (c. 40 Ma) and fossil cormorants appearing soon thereafter, the origin of the darters as a distinct lineage was presumably around 50–40 Ma, maybe a bit earlier.[23]

Fossil Anhingidae are known since the Early Miocene; a number of prehistoric darters similar to those still alive have been described, as well as some more distinct genera now extinct. The diversity was highest in South America, and thus it is likely that the family originated there. Some of the genera which ultimately became extinct were very large, and a tendency to become flightless has been noted in prehistoric darters. Their distinctness has been doubted, but this was due to the supposed "Anhinga" fraileyi being rather similar to Macranhinga, rather than due to them resembling the living species:[24]

- Meganhinga Alvarenga, 1995 (Early Miocene of Chile)

- "Paranavis" (Middle/Late Miocene of Paraná, Argentina) – a nomen nudum[25]

- Macranhinga Noriega, 1992 (Middle/Late Miocene – Late Miocene/Early Pliocene of SC South America) – may include "Anhinga" fraileyi

- Giganhinga Rinderknecht & Noriega, 2002 (Late Pliocene/Early Pleistocene of Uruguay)

- Anhinga

Prehistoric members of Anhinga were presumably distributed in similar climates as today, ranging into Europe in the hotter and wetter Miocene. With their considerable stamina and continent-wide distribution abilities (as evidenced by the anhinga and the Old World superspecies), the smaller lineage has survived for over 20 Ma. As evidenced by the fossil species' biogeography centered around the equator, with the younger species ranging eastwards out of the Americas, the Hadley cell seems to have been the main driver of the genus' success and survival:[26]

- Anhinga walterbolesi Worthy, 2012 (Late Oligocene to Early Miocene of central Australia

- Anhinga subvolans (Brodkorb, 1956) (Early Miocene of Thomas Farm, US) – formerly in Phalacrocorax[27]

- Anhinga cf. grandis (Middle Miocene of Colombia –? Late Pliocene of SC South America)[28]

- Anhinga sp. (Sajóvölgyi Middle Miocene of Mátraszõlõs, Hungary) – A. pannonica?[29]

- "Anhinga" fraileyi Campbell, 1996 (Late Miocene –? Early Pliocene of SC South America) – may belong in Macranhinga[30]

- Anhinga pannonica Lambrecht, 1916 (Late Miocene of C Europe ?and Tunisia, East Africa, Pakistan and Thailand –? Sahabi Early Pliocene of Libya)[31]

- Anhinga minuta Alvarenga & Guilherme, 2003 (Solimões Late Miocene/Early Pliocene of SC South America)[32]

- Anhinga grandis Martin & Mengel, 1975 (Late Miocene –? Late Pliocene of US)[33]

- Anhinga malagurala Mackness, 1995 (Allingham Early Pliocene of Charters Towers, Australia)[34]

- Anhinga sp. (Early Pliocene of Bone Valley, US) – A. beckeri?[35]

- Anhinga hadarensis Brodkorb & Mourer-Chauviré, 1982 (Late Pliocene/Early Pleistocene of E Africa)[36]

- Anhinga beckeri Emslie, 1998 (Early – Late Pleistocene of SE US)[35]

Protoplotus, a small Paleogene phalacrocoraciform from Sumatra, was in old times considered a primitive darter. However, it is also placed in its own family (Protoplotidae) and might be a basal member of the Sulae and/or close to the common ancestor of cormorants and darters.[37]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Walter J. Bock (1994): History and Nomenclature of Avian Family-Group Names. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, number 222; with application of article 36 of ICZN.

- ^ a b Answers.com [2009], BLI (2009), Myers et al. [2009]

- ^ Brodkorb & Mourer-Chauviré (1982), Myers et al. [2009]

- ^ a b c d Myers et al. [2009]

- ^ E.g. Centrarchidae (sunfishes), Cichlidae (cichlids), Cyprinidae (carps, minnows and relatives), Cyprinodontidae (pupfishes), Mugilidae (mullets), Plotosidae (eeltail catfishes) and Poeciliidae (livebearers): Myers et al. [2009]

- ^ E.g. Anura (frogs and toads), Caudata (newts and salamanders), snakes, turtles and even baby crocodilians: Myers et al. [2009]

- ^ E.g. Crustacea (crabs, crayfish and shrimps), insects, leeches and mollusks: Myers et al. [2009]

- ^ Ryan, PG (2007). "Diving in shallow water: the foraging ecology of darters (Aves: Anhingidae)". J. Avian Biol. 38 (4): 507–514. doi:10.1111/j.2007.0908-8857.04070.x.

- ^ Ryan, Peter G. (2014). "Moult of Flight Feathers in Darters (Anhingidae)". Ardea. 101 (4): 177–180. doi:10.5253/078.101.0213. S2CID 86476224.

- ^ a b Kennedy et al. (1996), Myers et al. [2009]

- ^ Answers.com [2009], Myers et al. [2009]

- ^ AnAge [2009], Myers et al. [2009]

- ^ Brisson, Mathurin Jacques (1760). Ornithologie, ou, Méthode Contenant la Division des Oiseaux en Ordres, Sections, Genres, Especes & leurs Variétés (in French and Latin). Paris: Jean-Baptiste Bauche. Vol. 1, p. 60, Vol. 6, p. 476.

- ^ Mayr, Ernst; Cottrell, G. William, eds. (1979). Check-list of Birds of the World. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Museum of Comparative Zoology. p. 170.

- ^ Jobling (1991): p.48, MW [2009]

- ^ E.g. genera like Borvocarbo, Limicorallus or Piscator: Mayr (2009): pp.65–67

- ^ Brodkorb & Mourer-Chauviré (1982), Olson (1985): p.207, Becker (1986), Christidis & Boles (2008): p.100, Mayr (2009): pp.67–70, Myers et al. [2009]

- ^ Kennedy et al. (1996)

- ^ Christidis & Boles (2008): p.100, Answers.com [2009], Mayr (2009): pp.67–70, Myers et al. [2009]

- ^ Gill, Frank; Donsker, David, eds. (2019). "Hamerkop, Shoebill, pelicans, boobies, cormorants". World Bird List Version 9.1. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- ^ Olson (1985): p.207, Becker (1986)

- ^ Miller (1966), Olson (1975), Brodkorb & Mourer-Chauviré (1982), Olson (1985): p.206, Mackness (1995)

- ^ Becker (1986), Mayr (2009): pp.67–70

- ^ Cione et al. (2000), Alvarenga & Guilherme (2003)

- ^ Named in a thesis and hence not validly according to ICZN rules. An apparently flightless species the size of A. anhinga: Noriega (1994), Cione et al. (2000)

- ^ Olson (1985): p.206

- ^ UF 4500, a proximal right humerus half. About 15% larger than A. anhinga and more plesiomorphic: Brodkorb (1956), Becker (1986)

- ^ Including a distal right humerus (UFAC-4721) from the Solimões Formation of Cachoeira do Bandeira (Acre, Brazil). Size identical to A. grandis, but distinctness in space and time makes assignment to that species questionable: Mackness (1995), Alvarenga & Guilherme (2003)

- ^ An ungual phalanx: Gál et al. (1998–99), Mlíkovský (2002): p.74

- ^ Holotype LACM 135356 is a slightly damaged right tarsometatarsus; other material includes a distal left ulna end (LACM 135361), a well-preserved left tibiotarsus (LACM 135357), two cervical vertebrae (LACM 135357-135358), three humerus pieces (LACM 135360, 135362-135363), probably also the almost complete left humerus UFAC-4562. A rather short-winged species about two-thirds larger than A. anhinga; apparently distinct from the living genus: Campbell (1992), Alvarenga & Guilherme (2003)

- ^ a cervical vertebra (the holotype) and a carpometacarpus; additional material includes another cervical vertebra and femur, humerus, tarsometatarsus and tibiotarsus pieces. About as large as A. rufa, apparently ancestral to the Old World lineages: Martin & Mengel (1975), Brodkorb & Mourer-Chauviré (1982), Olson (1985): p.206, Becker (1986), Mackness (1995), Mlíkovský (2002): p.73

- ^ UFAC-4720 (holotype, an almost complete left tibiotarsus) and UFAC-4719 (almost complete left humerus). The smallest known darter (30% smaller than A. anhinga), probably not very closely related to any living species: Alvarenga & Guilherme (2003)

- ^ Assorted material, including the holotype UNSM 20070 (a distal humerus end) and UF 25739 (another humerus piece). Longer-winged, about 25% larger than and twice as heavy as A. anhinga, but apparently a close relative: Martin & Mengel (1975), Olson (1985): p.206, Becker (1986), Campbell (1992)

- ^ QM F25776 (holotype, right carpometacarpus) and QM FF2365 (right proximal femur piece). Slightly smaller than A. melanogaster and apparently quite distinct: Becker (1986), Mackness (1995)

- ^ a b Ulna fossils larger than A. anhinga: Becker (1986)

- ^ The holotype is a well-preserved left femur (AL 288-52). Additional material consists of a proximal left femur (AL 305-2), a distal left tibiotarsus (L 193-78), a proximal (AL 225-3) and a distal (11 234) left ulna, a proximal left carpometacarpus (W 731), and well-preserved (10 736) and fragmentary (2870) right coracoids. Slightly smaller than A. rufa and probably its direct ancestor: Brodkorb & Mourer-Chauviré (1982), Olson (1985): p.206

- ^ Olson (1985): p.206, Mackness (1995), Mayr (2009): pp.62–63

General and cited sources

[edit]- Alvarenga, Herculano M.F.; Guilherme, Edson (2003). "The anhingas (Aves: Anhingidae) from the upper tertiary (Miocene-Pliocene) of southwestern Amazonia". J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 23 (3): 614–621. Bibcode:2003JVPal..23..614A. doi:10.1671/1890. S2CID 84072750.

- AnAge [2009]: Anhinga longevity data. Retrieved 2009-SEP-09.

- Answers.com [2009]: darter. In: Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia (6th ed.). Columbia University Press. Retrieved 2009-Sep-09.

- Becker, Jonathan J. (1986). "Reidentification of "Phalacrocorax" subvolans Brodkorb as the earliest record of Anhingidae" (PDF). Auk. 103 (4): 804–808. doi:10.1093/auk/103.4.804. JSTOR 4087190.

- Brodkorb, Pierce (1956). "Two New Birds from the Miocene of Florida" (PDF). Condor. 58 (5): 367–370. doi:10.2307/1365055. JSTOR 1365055. S2CID 86895919.

- Brodkorb, Pierce; Mourer-Chauviré, Cécile (1982). "Fossil anhingas (Aves: Anhingidae) from Early Man sites of Hadar and Omo (Ethiopia) and Olduvai Gorge (Tanzania)". Géobios. 15 (4): 505–515. Bibcode:1982Geobi..15..505B. doi:10.1016/S0016-6995(82)80071-5.

- BirdLife International (2016). "Anhinga melanogaster". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016 e.T22696712A93582012. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22696712A93582012.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Campbell, K.E. Jr. (1996). "A new species of giant anhinga (Aves: Pelecaniformes: Anhingidae) from the upper Miocene (Huayquerian) of Amazonian Peru". Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Contributions in Science. 460: 1–9.

- Christidis, Les & Boles, Walter E. (2008): Systematics and Taxonomy of Australian Birds. CSIRO Publishing, CollingwoodVictoria, Australia. ISBN 978-0-643-06511-6

- Cione, Alberto Luis; de las Mercedes Azpelicueta, María; Bond, Mariano; Carlini, Alfredo A.; Casciotta, Jorge R.; Cozzuol, Mario Alberto; de la Fuente, Marcelo; Gasparini, Zulma; Goin, Francisco J.; Noriega, Jorge; Scillatoyané, Gustavo J.; Soibelzon, Leopoldo; Tonni, Eduardo Pedro; Verzi, Diego & Guiomar Vucetich, María (2000): Miocene vertebrates from Entre Ríos province, eastern Argentina[permanent dead link]. [English with Spanish abstract] In: Aceñolaza, F.G. & Herbst, R. (eds.): El Neógeno de Argentina. INSUGEO Serie Correlación Geológica 14: 191–237.

- Gál, Erika; Hír, János; Kessler, Eugén; Kókay, József (1998–99). "Középsõ-miocén õsmaradványok, a Mátraszõlõs, Rákóczi-kápolna alatti útbevágásból. I. A Mátraszõlõs 1. lelõhely" [Middle Miocene fossils from the sections at the Rákóczi chapel at Mátraszőlős. Locality Mátraszõlõs I.] (PDF). Folia Historico Naturalia Musei Matraensis (in Hungarian and English). 23: 33–78. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-21. Retrieved 2007-02-06.

- Jobling, James A. (1991): A Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK. ISBN 0-19-854634-3

- Kennedy, Martyn; Spencer, Hamish G.; Gray, Russell D. (1996). "Hop, step and gape: do the social displays of the Pelecaniformes reflect phylogeny? Animal Behaviour". Animal Behaviour. 51 (2): 273–291. doi:10.1006/anbe.1996.0028. S2CID 53202305. "Erratum". Animal Behaviour. 51 (5): 1197. 1996. doi:10.1006/anbe.1996.0124. S2CID 235331320.

- Mackness, Brian (1995). "Anhinga malagurala, a New Pygmy Darter from the Early Pliocene Bluff Downs Local Fauna, North-eastern Queensland". Emu. 95 (4): 265–271. Bibcode:1995EmuAO..95..265M. doi:10.1071/MU9950265.

- Martin, Larry; Mengel, R.G. (1975). "A new species of anhinga (Anhingidae) from the Upper Pliocene of Nebraska" (PDF). Auk. 92 (1): 137–140. doi:10.2307/4084425. JSTOR 4084425.

- Mayr, Gerald (2009): Paleogene Fossil Birds. Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg & New York. ISBN 3-540-89627-9

- Merriam-Webster (MW) [2009]: Online English Dictionary – Anhinga. Retrieved 2009-Sep-09.

- Miller, Alden H. (1966). "An Evaluation of the Fossil Anhingas of Australia" (PDF). Condor. 68 (4): 315–320. doi:10.2307/1365447. JSTOR 1365447. S2CID 87211599.

- Mlíkovský, Jirí (2002): Cenozoic Birds of the World (Part 1: Europe). Ninox Press, Prague.

- Myers, P.; Espinosa, R.; Parr, C.S.; Jones, T.; Hammond, G.S. & Dewey, T.A. [2009]: Animal Diversity Web – Anhingidae. Retrieved 2009-Sep-09.

- Noriega, Jorge Ignacio (1994): Las Aves del "Mesopotamiense" de la provincia de Entre Ríos, Argentina ["The birds of the 'Mesopotamian' of Entre Ríos Province, Argentina"]. Doctoral thesis, Universidad Nacional de La Plata [in Spanish]. PDF abstract

- Olson, Storrs L. (1975). "An Evaluation of the Supposed Anhinga of Mauritius" (PDF). Auk. 92 (2): 374–376. doi:10.2307/4084567. JSTOR 4084567.

- Olson, Storrs L. (1985). "The Fossil Record of Birds" (PDF). Avian Biology. 8: 206–207 (Section X.G.5.c. Anhingidae). doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-249408-6.50011-x. ISBN 978-0-12-249408-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-18. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

External links

[edit]Darter

View on GrokipediaTaxonomy and systematics

Classification

Darters, referring to the fishes of the subfamily Etheostomatinae, occupy the following position in the taxonomic hierarchy: kingdom Animalia, phylum Chordata, class Actinopterygii, order Perciformes, suborder Percoidei, family Percidae, subfamily Etheostomatinae.[6] This subfamily encompasses several genera, with the most prominent being Etheostoma, Percina, Ammocrypta, Crystallaria, and Allohistium, which collectively account for the majority of darter diversity.[11] The Etheostomatinae is distinguished from other percid subfamilies, such as Luciopercinae (containing walleyes and sauger of the genus Sander) and Percinae (including the yellow perch of the genus Perca), by key morphological adaptations suited to a bottom-dwelling lifestyle. These include a greatly reduced or absent swim bladder, which impairs sustained swimming and favors benthic habitats, as well as elongate pectoral fins that enable precise maneuvering and "walking" along substrates.[12][13] Etheostominae supports approximately 250 extant species, rendering it one of North America's most species-rich assemblages of freshwater fishes.[14] Recent discoveries as of 2025, including two new Etheostoma species and splits in the Percina evides complex, suggest the total may exceed 260.[15][16] Species diversity is concentrated in the major genera, with Etheostoma comprising over 150 species, Percina approximately 55 species, Ammocrypta 6 species, Crystallaria 2 species, and Allohistium 2 species.[17][18][19][20] Post-2000 taxonomic revisions, informed by molecular phylogenetics, have refined darter classification through species splits and the promotion of subgenera to genera. Notable examples include the 2019 elevation of the Etheostoma subgenus Allohistium to full generic status, supported by phylogenomic data revealing deep evolutionary divergence.[21][22]Evolution and fossil record

Darters, comprising the subfamily Etheostomatinae within the family Percidae, originated in eastern North America during the Oligocene epoch, with molecular phylogenetic analyses estimating the crown age of the clade between 30.7 and 38.4 million years ago (Ma).[23] This divergence from other percid lineages, such as the perches (Perca) and pikes (Sander), is linked to adaptations for riverine habitats following the retreat of ancient seaways and the development of post-Eocene freshwater systems in the region.[24] The initial radiation of darters filled ecological niches in streams and rivers, characterized by small body sizes and benthic lifestyles that distinguished them from larger percid relatives.[6] Key drivers of darter diversification include allopatric speciation facilitated by Pleistocene glaciations, which isolated populations in glacial refugia and fragmented river drainages, promoting endemism across southeastern North American watersheds.[25] For instance, repeated cycles of glaciation and interglacials led to vicariance events, with many lineages diverging during the last 4 million years, particularly in genera like Percina and Etheostoma.[26] Sexual selection has also played a significant role, driving the evolution of elaborate male nuptial coloration and patterns through female mate choice and male-male competition, contributing to reproductive isolation and rapid speciation in sympatric populations.[27] The fossil record of darters is sparse, primarily due to the challenges of preserving small-bodied freshwater fishes in sedimentary deposits, with no confirmed Etheostomatinae fossils predating the Miocene.[6] Earliest potential darter-like remains, tentatively assignable to early members of the clade, occur in Miocene sediments from eastern North American river systems, dated approximately 5–23 Ma, though specific genera such as Etheostoma or Percina lack unambiguous pre-Pleistocene fossils.[28] In contrast, non-darter percids have a more robust record extending to the early Miocene, providing indirect calibration for percid timelines but highlighting the taphonomic biases against darter preservation.[29] Phylogenetic studies utilizing mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequences reveal a rapid radiation within Etheostomatinae over the past 5 million years, with molecular clock estimates indicating accelerated speciation rates in the Pliocene and Pleistocene.[30] Comprehensive cladograms from these analyses depict a well-resolved tree encompassing major genera (e.g., Etheostoma, Percina, Ammocrypta, Crystallaria, Allohistium), showing deep divergences among subgenera like Catonotus and Ulocentra, and underscoring the clade's monophyly within Percidae.[6] This recent burst aligns with geological events like river captures and climatic oscillations, explaining the current high species diversity of over 250 taxa.[23]Physical characteristics

Morphology

Darters exhibit a distinctive elongate, perch-like body plan adapted to their benthic lifestyle in streams and rivers. These fish are typically small, ranging from 5 to 15 cm in total length, though some species in the genus Percina can reach up to 20 cm.[31] The body is covered in ctenoid scales, providing flexibility and protection, while the single dorsal fin is divided into an anterior spinous portion with 7–18 spines and a posterior soft-rayed portion with 8–15 rays. The caudal fin is generally rounded, aiding in precise maneuvering rather than sustained swimming.[32] Specialized anatomical features support their bottom-dwelling habits. Most darters have a reduced or absent swim bladder, which limits buoyancy and keeps them close to the substrate.[1] Large pectoral fins, often fan-like and positioned high on the body, enable effective station-holding and darting movements in fast currents. Mouth morphology varies by genus; for instance, species in Etheostoma typically feature an inferior mouth suited for bottom foraging, with short gill rakers adapted for capturing small invertebrates from the substrate.[14][32] Growth is rapid, with individuals reaching sexual maturity in their first year at lengths of 4–8 cm, and lifespans generally lasting 1–3 years.[33][34] Sensory adaptations include an enhanced lateral line system along the body and head, which detects vibrations and water movements in turbulent stream environments, facilitating navigation and prey detection.[35]Coloration and variation

Darters generally display cryptic coloration adapted for their benthic stream environments, featuring mottled or barred patterns in shades of brown, olive, green, and tan that provide camouflage against substrates like gravel and sand.[36] These subdued hues are prevalent in both juveniles and non-breeding adults across genera such as Percina and Etheostoma, aiding in evasion of predators by blending with the riffle and pool bottoms they inhabit.[36] Sexual dimorphism in coloration is pronounced, particularly during the breeding season from spring to mid-summer, when males develop vivid nuptial hues to attract mates and compete intrasexually, while females retain duller, cryptic patterns for protection.[36] For instance, male orangethroat darters (Etheostoma spectabile) exhibit bright red spots along the sides, an orange throat, and blue-green accents on the head and fins, contrasting with the drab browns of females.[37] Similarly, male rainbow darters (E. caeruleum) display iridescent blue-green body hues with red markings on the anal and caudal fins, features absent or muted in females.[37] Males may also develop nuptial tubercles alongside these intensified colors, enhancing visual signals during courtship.[38] Intraspecific variation occurs at both ontogenetic and geographic scales, with juveniles showing achromatic, cryptic patterns that transition to conspicuous adult coloration as they mature and face reduced predation risk due to size or habitat shifts.[38] Within species, populations differ in color intensity; for example, E. spectabile from the Kaskaskia River exhibit bluer and more orange male breeding colors compared to those from other drainages, reflecting local adaptations. Interspecific variation further diversifies patterns, such as the presence of red on the anal fin in E. caeruleum versus its absence in E. spectabile, which aids in taxonomic identification of closely related species. Overall, the Etheostomatinae subfamily demonstrates exceptional color diversity, with over 150 species varying from basal cryptic forms to derived, multi-hued displays.[36]Habitat and distribution

Geographic range

Darters, in the subfamily Etheostomatinae of the family Percidae, comprising genera such as Etheostoma, Percina, Ammocrypta, and Crystallaria, are exclusively distributed across North America, with their range spanning the Great Lakes region, the Mississippi River basin, and eastward to the Atlantic seaboard as far north as southern Quebec and Ontario. This distribution is confined to the eastern and central portions of the continent, where suitable freshwater habitats persist, but darters are notably absent from the western United States, primarily due to the arid climate of the Great Plains and the impassable barrier of the Rocky Mountains that prevents eastward dispersal from Pacific drainages.[40][41][42] The southeastern United States represents the primary hotspot of darter diversity, hosting the majority of the approximately 250 recognized species, with concentrations in river systems such as the Tennessee and Cumberland, where over 150 species occur. Disjunct populations extend northward into Canada, including isolated occurrences of species like the eastern sand darter in Ontario and Quebec drainages connected to the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence system. This regional concentration underscores the historical connectivity of eastern North American waterways, though many populations remain fragmented today. Endemism is a defining feature of darter distributions, with a high proportion of species—often exceeding 80% in certain genera—restricted to individual river basins or even smaller tributaries, reflecting limited dispersal capabilities and habitat specialization. For instance, the Okaloosa darter (Etheostoma okaloosae) is confined to just six small stream drainages within the Choctawhatchee River system on Eglin Air Force Base in northwestern Florida, spanning less than 200 square kilometers. Similarly, species like the Yazoo darter (Etheostoma raneyi) are limited to headwater streams in the Yazoo River basin of Mississippi. This pattern of localized endemism heightens vulnerability to localized disturbances but also highlights the biodiversity richness of southeastern hotspots.[43][44] Historically, darter distributions were shaped by post-glacial recolonization following the retreat of the Laurentide Ice Sheet around 10,000–12,000 years ago, with many species dispersing northward from southern refugia in the Mississippi and Atlantic coastal plains into previously glaciated areas like the Great Lakes basin. Genetic studies of species such as the rainbow darter (Etheostoma caeruleum) reveal distinct phylogeographic patterns consistent with multiple refugia and subsequent range expansions along river corridors. In recent decades, climate warming has facilitated northward range shifts in some populations; for example, the goldline darter (Percina aurolineata) has shown evidence of expansion into higher latitudes within the Cahaba River system by the early 2020s, potentially tracking warmer water temperatures.[45][46][47]Environmental preferences

Darters, members of the family Percidae, primarily inhabit cool, clear, oxygen-rich streams and rivers characterized by gravel or rocky substrates, with a strong preference for riffles and runs over deeper pools. These benthic fishes thrive in moderate to swift currents that maintain high dissolved oxygen levels, typically exceeding 6 mg/L, which supports their active foraging behaviors.[48] Microhabitat specialization varies by genus, reflecting adaptations to specific substrates and positions within the water column. Species in the genus Ammocrypta, known as sand darters, favor sandy bottoms where they can bury themselves for concealment and spawning. In contrast, genera like Percina often occupy deeper channels with cobble or boulder substrates, while many Etheostoma species are associated with shallower, rocky riffles. Overall, darters are predominantly benthic, though some exhibit mid-water tendencies in low-flow areas.[49][50] Water quality is critical for darter survival, with optimal pH ranging from 7.0 to 8.5 and temperatures between 10°C and 25°C, though breeding often occurs at 15–18°C. These species are highly sensitive to sedimentation, which clogs gills and buries substrates, and to pollution that reduces oxygen availability or alters chemistry.[34][48] Seasonal variations influence habitat use, with darters migrating to shallower riffles during the breeding season (typically April to June) for spawning on clean gravel. In winter, they shift to deeper, slower waters for overwintering, seeking stable temperatures and reduced flow to conserve energy.[48][51]Behavior and ecology

Feeding habits

Darters primarily consume aquatic insects, with chironomid larvae often comprising over 50% of their diet by number, alongside mayflies (Ephemeroptera, such as baetids), caddisflies (Trichoptera), and blackflies (Simuliidae).[52][53] Microcrustaceans like ostracods and hydracarines, as well as occasional algae or fish eggs, supplement this insectivorous base, though larger species such as Percina evides may incorporate small fish.[54][55] Foraging occurs mainly on the stream bottom, where darters glean or pick prey from substrates using their pectoral fins to hover or position themselves in riffle interstices.[53] They exhibit diurnal activity patterns, with peak feeding intensity at dawn and dusk, such as around 0400 h and 2000 h for species like the fantail darter (Etheostoma flabellare), reflecting opportunistic benthic feeding on available invertebrates.[52] Seasonal variations align with insect availability, showing higher consumption of ephemeropterans and trichopterans in summer and fall.[55] Ontogenetic shifts in diet are common, with juveniles favoring smaller zooplankton and chironomids, while adults transition to larger prey items as body size increases, often around 30–34 mm standard length in species like the bayou darter (Etheostoma rubrum).[54][55] This shift from number-maximizing to prey-size selective tactics enhances foraging efficiency in larger individuals.[56] As secondary consumers in stream food webs, darters occupy a trophic level around 3.4, serving as key insectivores that link benthic invertebrates to higher predators.[57] Their reliance on pollution-sensitive aquatic insects positions darters as effective bioindicators of water quality, with dietary changes reflecting stream health.[58][59]Reproduction

Darters generally reproduce during the spring to early summer, with spawning triggered by rising water temperatures typically between 15°C and 20°C.[60][61] This period aligns with increased photoperiod and flow in streams, and females often undergo multiple spawning bouts over several weeks, releasing batches of eggs in successive events.[62] In southern populations, breeding may begin as early as February, while northern ones extend into late spring or early summer.[63] Mating behaviors in darters emphasize male territoriality, where individuals defend spawning sites against rivals through aggressive displays and chases. Courtship involves elaborate rituals, such as fin flaring, head bobbing, and rapid vibrations while mounting the female, often accompanied by intensified coloration to attract mates. In certain genera like Percina, males construct nests by arranging gravel into depressions or low mounds to receive eggs, enhancing protection within the substrate.[64][65] Reproductive strategies center on external fertilization, where females scatter demersal, adhesive eggs over the nest or substrate while the male simultaneously releases milt. Clutch sizes vary by species and female size but commonly range from 50 to 500 eggs per bout, reflecting high fecundity adapted to high environmental mortality. Many species feature male parental care, with guarding of nests to deter predators and maintain oxygenation, though some simply bury eggs without further attendance. Offspring survival in the wild remains low due to predation, abrasion, and desiccation risks.[62][66][67] The life cycle of darters exhibits variation between semelparity in short-lived, small-bodied species—which mature quickly, spawn once at age 1, and die—and iteroparity in longer-lived forms that breed over multiple seasons up to age 3-4. Larvae are initially pelagic before settling into benthic habitats, with maturity achieved within 6-12 months. Hybrid zones arise in areas of overlapping ranges, such as between Etheostoma caeruleum and E. spectabile, where incomplete reproductive isolation leads to interbreeding and occasional viable hybrids.[63][68] Recent research as of 2025 indicates interspecific variation in metabolic responses to warming temperatures among Etheostoma species, with some like the fantail darter showing elevated aerobic scope that may enhance resilience to climate-induced changes in spawning conditions.[69]Predation and interactions

Darters are preyed upon by a range of aquatic and avian predators, with juveniles exhibiting the highest vulnerability due to their small size and limited mobility. Prominent fish predators include largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides), northern pike (Esox lucius), yellow perch (Perca flavescens), sunfishes (Lepomis spp.), and pickerels (Esox niger).[70][71] Birds such as belted kingfishers (Megaceryle alcyon) and great blue herons (Ardea herodias) frequently consume darters in shallow riffles and streams.[72] Amphibians, including certain salamanders and frogs, may opportunistically prey on smaller individuals in overlapping habitats.[73] Several adaptations mitigate these predation risks. Darters detect predators via chemical cues released into the water, prompting behavioral shifts such as reduced activity or substrate relocation to minimize exposure.[73] Their cryptic coloration, which varies seasonally to match benthic substrates like gravel and algae-covered rocks, enhances camouflage against visual hunters.[74] In open water, some species form loose schools to confuse predators through collective movement. The family's name derives from their rapid darting escapes—quick, erratic bursts along the stream bottom that allow evasion of strikes.[75][76] Interspecific interactions encompass competition, parasitism, and infrequent mutualisms. Darters compete with benthic fishes like mottled sculpins (Cottus bairdii) for invertebrate prey and interstitial spaces in riffles, where resource overlap can limit population densities.[77][78] Trematode parasites, including heterophyids such as Centrocestus formosanus, commonly infect darter gills, causing hyperplasia, opercular flaring, and reduced respiratory efficiency, with prevalence up to 100% in affected populations like the endangered fountain darter (Etheostoma fonticola).[79][80] Rare mutualisms involve algae-covered substrates, where darters graze on periphyton while benefiting from habitat structure that deters predators.[81] As mid-trophic predators, darters serve a keystone function in stream ecosystems by controlling aquatic insect populations, preventing overabundance of herbivores that could degrade algal communities and water quality.[82][83] Invasive species exacerbate predation pressures; for instance, introduced rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) preferentially target native darters, altering community structure and reducing darter abundances in invaded streams.[84]Conservation and human impact

Threats

Darter populations face significant threats from habitat loss primarily driven by human activities such as dam construction, stream channelization, and urbanization, which fragment streams and alter natural flow regimes essential for their benthic lifestyles.[85] For instance, in the southeastern United States, these modifications have contributed to substantial declines in many darter species since the 1970s, with some experiencing over 50% reductions in their historical ranges due to siltation and riparian vegetation removal.[86][87] Pollution poses another major risk, particularly from agricultural runoff that leads to siltation and eutrophication, smothering spawning gravel beds and reducing water quality in riffle habitats favored by darters.[88] In Appalachian regions, acid mine drainage further exacerbates these issues by lowering pH levels, which is lethal to pH-sensitive species like the diamond darter, causing ongoing population stress from historical mining legacies.[89] Climate change intensifies these pressures through warming stream temperatures and altered hydrological patterns, which diminish suitable riffle habitats and increase thermal stress for cold-water adapted darters.[90] Droughts compound isolation in fragmented streams, while projections indicate that under moderate warming scenarios (~3 °C by 2050), up to 36% of global freshwater fish species may have more than 50% of their range exposed to novel climate extremes, potentially leading to significant range contractions.[91] Overexploitation through bait fishing directly removes individuals from vulnerable populations, particularly for smaller darter species harvested for angling bait, potentially leading to localized depletions.[92] Additionally, invasive species threaten darters via competition and hybridization; for example, the introduced fringed darter competes with and hybridizes with the native Barrens darter, eroding genetic integrity in shared habitats.[93] Urban development projects, such as proposed data centers, pose acute risks to endemic species; a November 2025 petition seeks Endangered Species Act protection for the Birmingham darter (Etheostoma birminghamense) due to threats to its limited habitat in Alabama's Valley Creek from such development.[94]Conservation measures

Conservation measures for darters encompass a range of legal protections, habitat restoration initiatives, captive breeding programs, and ongoing monitoring efforts aimed at stabilizing and recovering populations of these imperiled freshwater fish. Under the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, numerous darter species are classified as vulnerable or endangered due to habitat degradation and other pressures; for instance, the spotted darter (Etheostoma maculatum) is assessed as vulnerable globally. In the United States, the Endangered Species Act (ESA) provides federal protections for multiple darter species, with approximately 15 taxa listed as endangered or threatened since the 2010s, including the diamond darter (Crystallaria cincotta), listed in 2013 to safeguard its limited habitat in the Ohio River basin.[95] Other notable listings include the candy darter (Etheostoma osburni) in 2018 and the recent proposal for the Barrens darter (Etheostoma forbesi) in 2025, reflecting proactive measures to address range contractions.[96][97] Recovery efforts focus on habitat restoration, particularly in the Tennessee River system, where stream cleanups and dam removals have enhanced water quality and connectivity for species like the boulder darter (Etheostoma wapiti). By the 2020s, these interventions, including the removal of obsolete dams such as the one on Citico Creek, have reconnected over 1,100 miles of stream habitat, facilitating natural dispersal and spawning.[98][99] Captive breeding and reintroduction programs have also proven effective; for example, Conservation Fisheries has propagated boulder darters in controlled facilities since the 1980s, releasing them into restored reaches of the Tennessee River to bolster wild populations.[100] Similarly, the snail darter (Percina tanasi) benefited from such efforts, leading to its delisting in 2022 after reintroductions and improved river management practices increased its distribution across multiple tributaries.[101] Monitoring and research play a critical role in conservation, with genetic studies addressing hybridization risks that threaten species integrity. In the case of the candy darter, research has documented widespread introgressive hybridization with the introduced variegate darter (Etheostoma variatum), prompting targeted genetic screening to identify pure individuals for reintroduction and to mitigate gene swamping.[102][96] Citizen science initiatives, such as the MyCatch app, enable anglers to log fish observations, contributing data on darter distributions and abundances to support population tracking by fisheries managers.[103] Although darters are primarily North American endemics with limited transboundary distributions, international collaborations through frameworks like the International Freshwater Treaties Database facilitate broader river basin management, indirectly benefiting shared aquatic habitats in U.S.-Canada border regions.[104] Success stories highlight the impact of these measures, including significant population rebounds in protected areas; for instance, the Okaloosa darter (Etheostoma okaloosae) saw its numbers surge to over 600,000 individuals by 2023, enabling its delisting after habitat protections and erosion control efforts since the 1970s.[105] The watercress darter (Etheostoma nuchale) experienced a marked increase in population estimates since the mid-1990s within its Spring Hill refuge, attributed to water quality improvements. The Roanoke logperch (Percina rex), known as the "king of the darters," was delisted in July 2025 following decades of restoration that expanded its range and population viability.[106] However, challenges persist, including insufficient funding for long-term monitoring and the need for climate adaptation strategies to counter warming streams and altered flow regimes that exacerbate habitat fragmentation for darters.[107] These ongoing issues underscore the importance of sustained investment to ensure recovery amid environmental changes.References

- https://stream-ecology.inhs.[illinois](/page/Illinois).edu/files/2021/04/Zhou_etal_2014_malebreedingcolorvariationinrainbowandorangethroatdarters.pdf