Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Fumarase

View on Wikipedia

| FH | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | FH, fumarate hydratase, HLRCC, LRCC, MCL, MCUL1, FMRD, Fumarate hydratase, HsFH | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| External IDs | OMIM: 136850; MGI: 95530; HomoloGene: 115; GeneCards: FH; OMA:FH - orthologs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Fumarase (or fumarate hydratase) is an enzyme (EC 4.2.1.2) that catalyzes the reversible hydration/dehydration of fumarate to malate. Fumarase comes in two forms: mitochondrial and cytosolic. The mitochondrial isoenzyme is involved in the Krebs cycle and the cytosolic isoenzyme is involved in the metabolism of amino acids and fumarate. Subcellular localization is established by the presence of a signal sequence on the amino terminus in the mitochondrial form, while subcellular localization in the cytosolic form is established by the absence of the signal sequence found in the mitochondrial variety.[5]

This enzyme participates in 2 metabolic pathways: citric acid cycle and reductive citric acid cycle (CO2 fixation), and is also important in renal cell carcinoma. Mutations in this gene have been associated with the development of leiomyomas in the skin and uterus in combination with renal cell carcinoma (HLRCC syndrome).

Nomenclature

[edit]This enzyme belongs to the family of lyases, specifically the hydro-lyases, which cleave carbon-oxygen bonds. The systematic name of this enzyme class is (S)-malate hydro-lyase (fumarate-forming). Other names in common use include:

- fumarase

- L-malate hydro-lyase

- (S)-malate hydro-lyase

Structure

[edit]Gene

[edit]

In humans, the FH gene is localized to the chromosomal position 1q42.3-q43. The FH gene contains 10 exons.

Protein

[edit]Crystal structures of fumarase C from Escherichia coli have been observed to have two dicarboxylate binding sites close to one another. These are known as the active site and the B site. These sites are connected by a series of hydrogen bonds and the access to either site is only through an opening near the enzyme surface near the B site.[6] Active site is made up of three domains. Even when no ligand is bound to the active site, the binding pocket created by surrounding residues is sufficient to bind water in its place.[6] Crystallographic research on the B site of the enzyme has observed that there is a shift on His129 between free and occupied states. It also suggests that the use of an imidazole-imidazolium conversion controls access to the allosteric B site.[6]

Subtypes

[edit]There are two classes of fumarases, class I and class II.[7] Classification depends on the arrangement of their relative subunits, their metal ion requirement, and their thermal stability. Class I fumarases are change state or become inactive when subjected to heat or radiation, are sensitive to superoxide anion, are iron (Fe2+) dependent, and are dimeric proteins with each subunit consisting of around 120 kD. Class II fumarases, found in prokaryotes as well as in eukaryotes, are tetrameric enzymes with subunits of 200 kD that contain three distinct segments of significantly homologous amino acids. They are also iron-independent and thermally stable. Prokaryotes are known to have three different forms of fumarase: Fumarase A, Fumarase B, and Fumarase C. Fumarase A and Fumarase B from Escherichia coli are classified as class I, whereas Fumarase C is a part of the class II fumarases.[8]

Function

[edit]Mechanism

[edit]

Figure 1 depicts the fumarase reaction mechanism. Two residues catalyze proton transfer and the ionization state of these residues is in part defined by two forms of the enzyme, E1 and E2. In E1, the groups exist in an internally neutralized AH/B: state, while in E2, they occur in a zwitterionic A−/BH+ state. E1 binds fumarate and facilitates its transformation into malate, and E2 binds malate and facilitates its transformation into fumarate. The two forms must undergo isomerization with each catalytic turnover.[9]

Despite its biological significance, the reaction mechanism of fumarase is not completely understood. The reaction itself can be monitored in either direction; however, it is the formation of fumarate from S-malate in particular that is less understood due to the high pKa value of the HR atom (Fig. 2) that is removed without the aid of any cofactors or coenzymes. The reaction from fumarate to S-malate is better understood, and involves a stereospecific hydration of fumarate to produce S-malate by trans-addition of a hydroxyl group and a hydrogen atom. Early research into this reaction suggested that the formation of fumarate from S-malate involved dehydration of malate to a carbocationic intermediate, which then loses the alpha proton to form fumarate. This led to the conclusion that the formation of S-malate proceeds as E1 elimination - protonation of fumarate to create a carbocation was followed by the addition of a hydroxyl group from H2O. However, more recent trials have provided evidence that the mechanism actually takes place through an acid-base catalyzed elimination by means of a carbanionic intermediate, meaning it proceeds as E1cB elimination (Figure 1).[9][10][11] This was investigated using isotopic labelling techniques, confirming a concerted mechanism[12]

Biochemical pathway

[edit]The function of fumarase in the citric acid cycle is to facilitate a transition step in the production of energy in the form of NADH.[13] In the cytosol, the enzyme functions to metabolize fumarate, which is a byproduct of the urea cycle as well as amino acid catabolism. Studies have revealed that the active site is composed of amino acid residues from three of the four subunits within the tetrameric enzyme.[8][9][10][11]

Other substrates

[edit]The main substrates for fumarase are malate and fumarate. However, the enzyme can also catalyze the dehydration of D-tartrate which results in enol-oxaloacetate. Enol-oxaloacetate can then izomerize into keto-oxaloacetate. Both Fumarase A and Fumarase B have essentially the same kinetics for the reversible malate to fumarase conversion, but Fumarase B has a much higher catalytic efficiency for the conversion of D-tartrate to oxaloacetate compared to Fumarase A.[14] This allows bacteria such as E. coli use D-tartrate for their growth; the growth of mutants with a disruptive gene fumB encoding Fumarase B on D-tartrate was severely impaired.[14]

Clinical significance

[edit]Fumarase deficiency is characterized by polyhydramnios and fetal brain abnormalities. In the newborn period, findings include severe neurologic abnormalities, poor feeding, failure to thrive, and hypotonia. Fumarase deficiency is suspected in infants with multiple severe neurologic abnormalities in the absence of an acute metabolic crisis. Inactivity of both cytosolic and mitochondrial forms of fumarase are potential causes. Isolated, increased concentration of fumaric acid on urine organic acid analysis is highly suggestive of fumarase deficiency. Molecular genetic testing for fumarase deficiency is currently available.[7]

Fumarase is prevalent in both fetal and adult tissues. A large percentage of the enzyme is expressed in the skin, parathyroid, lymph, and colon. Mutations in the production and development of fumarase have led to the discovery of several fumarase-related diseases in humans. These include benign mesenchymal tumors of the uterus, leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma, and fumarase deficiency. Germinal mutations in fumarase are associated with two distinct conditions. If the enzyme has missense mutation and in-frame deletions from the 3' end, fumarase deficiency results. If it contains heterozygous 5' missense mutation and deletions (ranging from one base pair to the whole gene), then leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma/Reed's syndrome (multiple cutaneous and uterine leiomyomatosis) could result.[8][7]

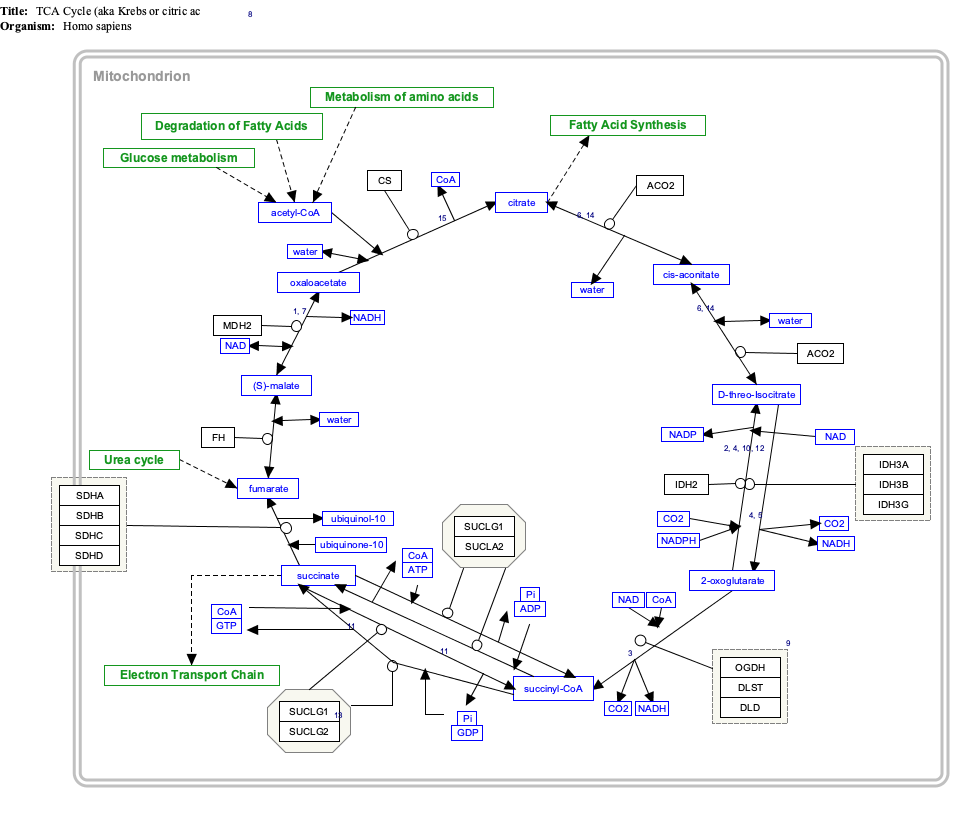

Interactive pathway map

[edit]Click on genes, proteins and metabolites below to link to respective articles. [§ 1]

- ^ The interactive pathway map can be edited at WikiPathways: "TCACycle_WP78".

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000091483 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000026526 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ FH (fumarate hydratase)

- ^ a b c Weaver T (October 2005). "Structure of free fumarase C from Escherichia coli". Acta Crystallographica. Section D, Biological Crystallography. 61 (Pt 10): 1395–1401. doi:10.1107/S0907444905024194. PMID 16204892.

- ^ a b c Lynch AM, Morton CC (2006-07-01). "FH (fumarate hydratase)". Atlas of Genetics and Cytogenetics in Oncology and Haematology.

- ^ a b c Estévez M, Skarda J, Spencer J, Banaszak L, Weaver TM (June 2002). "X-ray crystallographic and kinetic correlation of a clinically observed human fumarase mutation". Protein Science. 11 (6): 1552–1557. doi:10.1110/ps.0201502. PMC 2373640. PMID 12021453.

- ^ a b c Hegemony AD, Frey PA (2007). Enzymatic reaction mechanisms. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512258-9.

- ^ a b Begley TP, McMurry J (2005). The organic chemistry of biological pathways. Roberts and Co. Publishers. ISBN 978-0-9747077-1-6.

- ^ a b Walsh C (1979). Enzymatic reaction mechanisms. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-0070-8.

- ^ Jones VT, Lowe G, Potter BVL (1980). [doi/10.1111/j.1432-1033.1980.tb04739.x "Evidence against a step-wise mechanism for the fumarase-catalysed dehydration of (2S)-malate"]. Eur J Biochem. 108: 433–437.

{{cite journal}}: Check|url=value (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Yogev O, Naamati A, Pines O (November 2011). "Fumarase: a paradigm of dual targeting and dual localized functions". The FEBS Journal. 278 (22): 4230–4242. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08359.x. PMID 21929734.

- ^ a b van Vugt-Lussenburg BM, van der Weel L, Hagen WR, Hagedoorn PL (February 26, 2021). "Biochemical similarities and differences between the catalytic [4Fe-4S] cluster containing fumarases FumA and FumB from Escherichia coli". PLOS ONE. 8 (2) e55549. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0055549. PMC 3565967. PMID 23405168.

External links

[edit]- Fumarase at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Structure of Fumarate

- Structure of S-Malate

- Link to Breakdown of Citric Acid Cycle

- Video of Fumarate → (S)L-Malate Archived 2005-06-25 at the Wayback Machine