Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

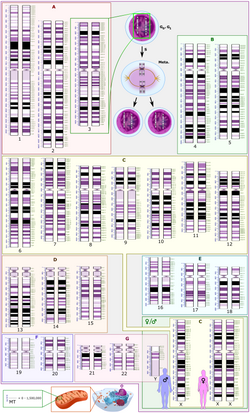

G0 phase

View on Wikipedia

The G0 phase describes a cellular state outside of the replicative cell cycle. Classically[when?], cells were thought to enter G0 primarily due to environmental factors, like nutrient deprivation, that limited the resources necessary for proliferation. Thus it was thought of as a resting phase. G0 is now known to take different forms and occur for multiple reasons. For example, most adult neuronal cells, among the most metabolically active cells in the body, are fully differentiated and reside in a terminal G0 phase. Neurons reside in this state, not because of stochastic or limited nutrient supply, but as a part of their developmental program.

G0 was first suggested as a cell state based on early cell cycle studies. When the first studies defined the four phases of the cell cycle using radioactive labeling techniques, it was discovered that not all cells in a population proliferate at similar rates.[1] A population's "growth fraction" – or the fraction of the population that was growing – was actively proliferating, but other cells existed in a non-proliferative state. Some of these non-proliferating cells could respond to extrinsic stimuli and proliferate by re-entering the cell cycle.[2] Early contrasting views either considered non-proliferating cells to simply be in an extended G1 phase or in a cell cycle phase distinct from G1 – termed G0.[3] Subsequent research pointed to a restriction point (R-point) in G1 where cells can enter G0 before the R-point but are committed to mitosis after the R-point.[4] These early studies provided evidence for the existence of a G0 state to which access is restricted. These cells that do not divide further exit G1 phase to enter an inactive stage called quiescent stage.

Diversity of G0 states

[edit]

Three G0 states exist and can be categorized as either reversible (quiescent) or irreversible (senescent and differentiated). Each of these three states can be entered from the G1 phase before the cell commits to the next round of the cell cycle. Quiescence refers to a reversible G0 state where subpopulations of cells reside in a 'quiescent' state before entering the cell cycle after activation in response to extrinsic signals. Quiescent cells are often identified by low RNA content, lack of cell proliferation markers, and increased label retention indicating low cell turnover.[5][6] Senescence is distinct from quiescence because senescence is an irreversible state that cells enter in response to DNA damage or degradation that would make a cell's progeny nonviable. Such DNA damage can occur from telomere shortening over many cell divisions as well as reactive oxygen species (ROS) exposure, oncogene activation, and cell-cell fusion. While senescent cells can no longer replicate, they remain able to perform many normal cellular functions.[7][8][9][10] Senescence is often a biochemical alternative to the self-destruction of such a damaged cell by apoptosis. In contrast to cellular senescence, quiescence is not a reactive event but part of the core programming of several different cell types. Finally, differentiated cells are stem cells that have progressed through a differentiation program to reach a mature – terminally differentiated – state. Differentiated cells continue to stay in G0 and perform their main functions indefinitely.

Characteristics of quiescent stem cells

[edit]Transcriptomes

[edit]The transcriptomes of several types of quiescent stem cells, such as hematopoietic, muscle, and hair follicle, have been characterized through high-throughput techniques, such as microarray and RNA sequencing. Although variations exist in their individual transcriptomes, most quiescent tissue stem cells share a common pattern of gene expression that involves downregulation of cell cycle progression genes, such as cyclin A2, cyclin B1, cyclin E2, and survivin, and upregulation of genes involved in the regulation of transcription and stem cell fate, such as FOXO3 and EZH1. Downregulation of mitochondrial cytochrome C also reflects the low metabolic state of quiescent stem cells.[11]

Epigenetic

[edit]Many quiescent stem cells, particularly adult stem cells, also share similar epigenetic patterns. For example, H3K4me3 and H3K27me3, are two major histone methylation patterns that form a bivalent domain and are located near transcription initiation sites. These epigenetic markers have been found to regulate lineage decisions in embryonic stem cells as well as control quiescence in hair follicle and muscle stem cells via chromatin modification.[11]

Regulation of quiescence

[edit]Cell cycle regulators

[edit]Functional tumor suppressor genes, particularly p53 and Rb gene, are required to maintain stem cell quiescence and prevent exhaustion of the progenitor cell pool through excessive divisions. For example, deletion of all three components of the Rb family of proteins has been shown to halt quiescence in hematopoietic stem cells. Lack of p53 has been shown to prevent differentiation of these stem cells due to the cells' inability to exit the cell cycle into the G0 phase. In addition to p53 and Rb, cyclin dependent kinase inhibitors (CKIs), such as p21, p27, and p57, are also important for maintaining quiescence. In mouse hematopoietic stem cells, knockout of p57 and p27 leads to G0 exit through nuclear import of cyclin D1 and subsequent phosphorylation of Rb. Finally, the Notch signaling pathway has been shown to play an important role in maintenance of quiescence.[11]

Post-transcriptional regulation

[edit]Post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression via miRNA synthesis has been shown to play an equally important role in the maintenance of stem cell quiescence. miRNA strands bind to the 3′ untranslated region (3′ UTR) of target mRNAs, preventing their translation into functional proteins. The length of the 3′ UTR of a gene determines its ability to bind to miRNA strands, thereby allowing regulation of quiescence. Some examples of miRNA's in stem cells include miR-126, which controls the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in hematopoietic stem cells, miR-489, which suppresses the DEK oncogene in muscle stem cells, and miR-31, which regulates Myf5 in muscle stem cells. miRNA sequestration of mRNA within ribonucleoprotein complexes allows quiescent cells to store the mRNA necessary for quick entry into the G1 phase.[11]

Response to stress

[edit]Stem cells that have been quiescent for a long time often face various environmental stressors, such as oxidative stress. However, several mechanisms allow these cells to respond to such stressors. For example, the FOXO transcription factors respond to the presence of reactive oxygen species (ROS) while HIF1A and LKB1 respond to hypoxic conditions. In hematopoietic stem cells, autophagy is induced to respond to metabolic stress.[11]

Examples of reversible G0 phase

[edit]Tissue stem cells

[edit]Stem cells are cells with the unique ability to produce differentiated daughter cells and to preserve their stem cell identity through self-renewal.[12] In mammals, most adult tissues contain tissue-specific stem cells that reside in the tissue and proliferate to maintain homeostasis for the lifespan of the organism. These cells can undergo immense proliferation in response to tissue damage before differentiating and engaging in regeneration. Some tissue stem cells exist in a reversible, quiescent state indefinitely until being activated by external stimuli. Many different types of tissue stem cells exist, including muscle stem cells (MuSCs), neural stem cells (NSCs), intestinal stem cells (ISCs), and many others.

Stem cell quiescence has been recently suggested to be composed of two distinct functional phases, G0 and an 'alert' phase termed GAlert.[13] Stem cells are believed to actively and reversibly transition between these phases to respond to injury stimuli and seem to gain enhanced tissue regenerative function in GAlert. Thus, transition into GAlert has been proposed as an adaptive response that enables stem cells to rapidly respond to injury or stress by priming them for cell cycle entry. In muscle stem cells, mTORC1 activity has been identified to control the transition from G0 into GAlert along with signaling through the HGF receptor cMet.[13]

Mature hepatocytes

[edit]While a reversible quiescent state is perhaps most important for tissue stem cells to respond quickly to stimuli and maintain proper homeostasis and regeneration, reversible G0 phases can be found in non-stem cells such as mature hepatocytes.[14] Hepatocytes are typically quiescent in normal livers but undergo limited replication (less than 2 cell divisions) during liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy. However, in certain cases, hepatocytes can experience immense proliferation (more than 70 cell divisions) indicating that their proliferation capacity is not hampered by existing in a reversible quiescent state.[14]

Examples of irreversible G0 phase

[edit]Senescent cells

[edit]Often associated with aging and age-related diseases in vivo, senescent cells can be found in many renewable tissues, including the stroma, vasculature, hematopoietic system, and many epithelial organs. Resulting from accumulation over many cell divisions, senescence is often seen in age-associated degenerative phenotypes. Senescent fibroblasts in models of breast epithelial cell function have been found to disrupt milk protein production due to secretion of matrix metalloproteinases.[15] Similarly, senescent pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells caused nearby smooth muscle cells to proliferate and migrate, perhaps contributing to hypertrophy of pulmonary arteries and eventually pulmonary hypertension.[16]

Differentiated muscle

[edit]During skeletal myogenesis, cycling progenitor cells known as myoblasts differentiate and fuse together into non-cycling muscle cells called myocytes that remain in a terminal G0 phase.[17] As a result, the fibers that make up skeletal muscle (myofibers) are cells with multiple nuclei, referred to as myonuclei, since each myonucleus originated from a single myoblast. Skeletal muscle cells continue indefinitely to provide contractile force through simultaneous contractions of cellular structures called sarcomeres. Importantly, these cells are kept in a terminal G0 phase since disruption of muscle fiber structure after myofiber formation would prevent proper transmission of force through the length of the muscle. Muscle growth can be stimulated by growth or injury and involves the recruitment of muscle stem cells – also known as satellite cells – out of a reversible quiescent state. These stem cells differentiate and fuse to generate new muscle fibers both in parallel and in series to increase force generation capacity.

Cardiac muscle is also formed through myogenesis but instead of recruiting stem cells to fuse and form new cells, heart muscle cells – known as cardiomyocytes – simply increase in size as the heart grows larger. Similarly to skeletal muscle, if cardiomyocytes had to continue dividing to add muscle tissue the contractile structures necessary for heart function would be disrupted.

Differentiated bone

[edit]Of the four major types of bone cells, osteocytes are the most common and also exist in a terminal G0 phase. Osteocytes arise from osteoblasts that are trapped within a self-secreted matrix. While osteocytes also have reduced synthetic activity, they still serve bone functions besides generating structure. Osteocytes work through various mechanosensory mechanisms to assist in the routine turnover over bony matrix.

Differentiated nerve

[edit]Outside of a few neurogenic niches in the brain, most neurons are fully differentiated and reside in a terminal G0 phase. These fully differentiated neurons form synapses where electrical signals are transmitted by axons to the dendrites of nearby neurons. In this G0 state, neurons continue functioning until senescence or apoptosis. Numerous studies have reported accumulation of DNA damage with age, particularly oxidative damage, in the mammalian brain.[18]

Mechanism of G0 entry

[edit]Role of Rim15

[edit]Rim15 was first discovered to play a critical role in initiating meiosis in diploid yeast cells. Under conditions of low glucose and nitrogen, which are key nutrients for the survival of yeast, diploid yeast cells initiate meiosis through the activation of early meiotic-specific genes (EMGs). The expression of EMGs is regulated by Ume6. Ume6 recruits the histone deacetylases, Rpd3 and Sin3, to repress EMG expression when glucose and nitrogen levels are high, and it recruits the EMG transcription factor Ime1 when glucose and nitrogen levels are low. Rim15, named for its role in the regulation of an EMG called IME2, displaces Rpd3 and Sin3, thereby allowing Ume6 to bring Ime1 to the promoters of EMGs for meiosis initiation.[19]

In addition to playing a role in meiosis initiation, Rim15 has also been shown to be a critical effector for yeast cell entry into G0 in the presence of stress. Signals from several different nutrient signaling pathways converge on Rim15, which activates the transcription factors, Gis1, Msn2, and Msn4. Gis1 binds to and activates promoters containing post-diauxic growth shift (PDS) elements while Msn2 and Msn4 bind to and activate promoters containing stress-response elements (STREs). Although it is not clear how Rim15 activates Gis1 and Msn2/4, there is some speculation that it may directly phosphorylate them or be involved in chromatin remodeling. Rim15 has also been found to contain a PAS domain at its N terminal, making it a newly discovered member of the PAS kinase family. The PAS domain is a regulatory unit of the Rim15 protein that may play a role in sensing oxidative stress in yeast.[19]

Nutrient signaling pathways

[edit]Glucose

[edit]Yeast grows exponentially through fermentation of glucose. When glucose levels drop, yeast shift from fermentation to cellular respiration, metabolizing the fermentative products from their exponential growth phase. This shift is known as the diauxic shift after which yeast enter G0. When glucose levels in the surroundings are high, the production of cAMP through the RAS-cAMP-PKA pathway (a cAMP-dependent pathway) is elevated, causing protein kinase A (PKA) to inhibit its downstream target Rim15 and allow cell proliferation. When glucose levels drop, cAMP production declines, lifting PKA's inhibition of Rim15 and allowing the yeast cell to enter G0.[19]

Nitrogen

[edit]In addition to glucose, the presence of nitrogen is crucial for yeast proliferation. Under low nitrogen conditions, Rim15 is activated to promote cell cycle arrest through inactivation of the protein kinases TORC1 and Sch9. While TORC1 and Sch9 belong to two separate pathways, namely the TOR and Fermentable Growth Medium induced pathways respectively, both protein kinases act to promote cytoplasmic retention of Rim15. Under normal conditions, Rim15 is anchored to the cytoplasmic 14-3-3 protein, Bmh2, via phosphorylation of its Thr1075. TORC1 inactivates certain phosphatases in the cytoplasm, keeping Rim15 anchored to Bmh2, while it is thought that Sch9 promotes Rim15 cytoplasmic retention through phosphorylation of another 14-3-3 binding site close to Thr1075. When extracellular nitrogen is low, TORC1 and Sch9 are inactivated, allowing dephosphorylation of Rim15 and its subsequent transport to the nucleus, where it can activate transcription factors involved in promoting cell entry into G0. It has also been found that Rim15 promotes its own export from the nucleus through autophosphorylation.[19]

Phosphate

[edit]Yeast cells respond to low extracellular phosphate levels by activating genes that are involved in the production and upregulation of inorganic phosphate. The PHO pathway is involved in the regulation of phosphate levels. Under normal conditions, the yeast cyclin-dependent kinase complex, Pho80-Pho85, inactivates the Pho4 transcription factor through phosphorylation. However, when phosphate levels drop, Pho81 inhibits Pho80-Pho85, allowing Pho4 to be active. When phosphate is abundant, Pho80-Pho85 also inhibits the nuclear pool of Rim 15 by promoting phosphorylation of its Thr1075 Bmh2 binding site. Thus, Pho80-Pho85 acts in concert with Sch9 and TORC1 to promote cytoplasmic retention of Rim15 under normal conditions.[19]

Mechanism of G0 exit

[edit]Cyclin C/Cdk3 and Rb

[edit]The transition from G1 to S phase is promoted by the inactivation of Rb through its progressive hyperphosphorylation by the Cyclin D/Cdk4 and Cyclin E/Cdk2 complexes in late G1. An early observation that loss of Rb promoted cell cycle re-entry in G0 cells suggested that Rb is also essential in regulating the G0 to G1 transition in quiescent cells.[20] Further observations revealed that levels of cyclin C mRNA are highest when human cells exit G0, suggesting that cyclin C may be involved in Rb phosphorylation to promote cell cycle re-entry of G0 arrested cells. Immunoprecipitation kinase assays revealed that cyclin C has Rb kinase activity. Furthermore, unlike cyclins D and E, cyclin C's Rb kinase activity is highest during early G1 and lowest during late G1 and S phases, suggesting that it may be involved in the G0 to G1 transition. The use of fluorescence-activated cell sorting to identify G0 cells, which are characterized by a high DNA to RNA ratio relative to G1 cells, confirmed the suspicion that cyclin C promotes G0 exit as repression of endogenous cyclin C by RNAi in mammalian cells increased the proportion of cells arrested in G0. Further experiments involving mutation of Rb at specific phosphorylation sites showed that cyclin C phosphorylation of Rb at S807/811 is necessary for G0 exit. It remains unclear, however, whether this phosphorylation pattern is sufficient for G0 exit. Finally, co-immunoprecipitation assays revealed that cyclin-dependent kinase 3 (cdk3) promotes G0 exit by forming a complex with cyclin C to phosphorylate Rb at S807/811. Interestingly, S807/811 are also targets of cyclin D/cdk4 phosphorylation during the G1 to S transition. This might suggest a possible compensation of cdk3 activity by cdk4, especially in light of the observation that G0 exit is only delayed, and not permanently inhibited, in cells lacking cdk3 but functional in cdk4. Despite the overlap of phosphorylation targets, it seems that cdk3 is still necessary for the most effective transition from G0 to G1.[21]

Rb and G0 exit

[edit]Studies suggest that Rb repression of the E2F family of transcription factors regulates the G0 to G1 transition just as it does the G1 to S transition. Activating E2F complexes are associated with the recruitment of histone acetyltransferases, which activate gene expression necessary for G1 entry, while E2F4 complexes recruit histone deacetylases, which repress gene expression. Phosphorylation of Rb by Cdk complexes allows its dissociation from E2F transcription factors and the subsequent expression of genes necessary for G0 exit. Other members of the Rb pocket protein family, such as p107 and p130, have also been found to be involved in G0 arrest. p130 levels are elevated in G0 and have been found to associate with E2F-4 complexes to repress transcription of E2F target genes. Meanwhile, p107 has been found to rescue the cell arrest phenotype after loss of Rb even though p107 is expressed at comparatively low levels in G0 cells. Taken together, these findings suggest that Rb repression of E2F transcription factors promotes cell arrest while phosphorylation of Rb leads to G0 exit via derepression of E2F target genes.[20] In addition to its regulation of E2F, Rb has also been shown to suppress RNA polymerase I and RNA polymerase III, which are involved in rRNA synthesis. Thus, phosphorylation of Rb also allows activation of rRNA synthesis, which is crucial for protein synthesis upon entry into G1.[21]

References

[edit]- ^ Howard A, Pelc SR (2009). "Synthesis of Desoxyribonucleic Acid in Normal and Irradiated Cells and Its Relation to Chromosome Breakage". International Journal of Radiation Biology and Related Studies in Physics, Chemistry and Medicine. 49 (2): 207–218. doi:10.1080/09553008514552501. ISSN 0020-7616.

- ^ Baserga R (2008). "Biochemistry of the Cell Cycle: A Review". Cell Proliferation. 1 (2): 167–191. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2184.1968.tb00957.x. ISSN 0960-7722. S2CID 86353634.

- ^ Patt HM, Quastler H (July 1963). "Radiation effects on cell renewal and related systems". Physiological Reviews. 43 (3): 357–96. doi:10.1152/physrev.1963.43.3.357. PMID 13941891.

- ^ Pardee AB (April 1974). "A restriction point for control of normal animal cell proliferation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 71 (4): 1286–90. Bibcode:1974PNAS...71.1286P. doi:10.1073/pnas.71.4.1286. PMC 388211. PMID 4524638.

- ^ Hüttmann, A (2001). "Functional heterogeneity within rhodamine123lo Hoechst33342lo/sp primitive hemopoietic stem cells revealed by pyronin Y". Experimental Hematology. 29 (9): 1109–1116. doi:10.1016/S0301-472X(01)00684-1. ISSN 0301-472X. PMID 11532352.

- ^ Fukada S, Uezumi A, Ikemoto M, Masuda S, Segawa M, Tanimura N, Yamamoto H, Miyagoe-Suzuki Y, Takeda S (October 2007). "Molecular signature of quiescent satellite cells in adult skeletal muscle". Stem Cells. 25 (10): 2448–59. doi:10.1634/stemcells.2007-0019. PMID 17600112.

- ^ Hayflick L, Moorhead PS (December 1961). "The serial cultivation of human diploid cell strains". Experimental Cell Research. 25 (3): 585–621. doi:10.1016/0014-4827(61)90192-6. PMID 13905658.

- ^ Campisi J (February 2013). "Aging, cellular senescence, and cancer". Annual Review of Physiology. 75: 685–705. doi:10.1146/annurev-physiol-030212-183653. PMC 4166529. PMID 23140366.

- ^ Rodier F, Campisi J (February 2011). "Four faces of cellular senescence". The Journal of Cell Biology. 192 (4): 547–56. doi:10.1083/jcb.201009094. PMC 3044123. PMID 21321098.

- ^ Burton DG, Krizhanovsky V (November 2014). "Physiological and pathological consequences of cellular senescence". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 71 (22): 4373–86. doi:10.1007/s00018-014-1691-3. PMC 4207941. PMID 25080110.

- ^ a b c d e Cheung TH, Rando TA (June 2013). "Molecular regulation of stem cell quiescence". Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology. 14 (6): 329–40. doi:10.1038/nrm3591. PMC 3808888. PMID 23698583.

- ^ Weissman IL (January 2000). "Stem cells: units of development, units of regeneration, and units in evolution". Cell. 100 (1): 157–68. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81692-X. PMID 10647940.

- ^ a b Rodgers JT, King KY, Brett JO, Cromie MJ, Charville GW, Maguire KK, Brunson C, Mastey N, Liu L, Tsai CR, Goodell MA, Rando TA (June 2014). "mTORC1 controls the adaptive transition of quiescent stem cells from G0 to G(Alert)". Nature. 510 (7505): 393–6. Bibcode:2014Natur.510..393R. doi:10.1038/nature13255. PMC 4065227. PMID 24870234.

- ^ a b Fausto N (June 2004). "Liver regeneration and repair: hepatocytes, progenitor cells, and stem cells". Hepatology. 39 (6): 1477–87. doi:10.1002/hep.20214. PMID 15185286.

- ^ Coppé JP, Patil CK, Rodier F, Sun Y, Muñoz DP, Goldstein J, Nelson PS, Desprez PY, Campisi J (December 2008). "Senescence-associated secretory phenotypes reveal cell-nonautonomous functions of oncogenic RAS and the p53 tumor suppressor". PLOS Biology. 6 (12): 2853–68. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0060301. PMC 2592359. PMID 19053174.

- ^ Noureddine H, Gary-Bobo G, Alifano M, Marcos E, Saker M, Vienney N, Amsellem V, Maitre B, Chaouat A, Chouaid C, Dubois-Rande JL, Damotte D, Adnot S (August 2011). "Pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell senescence is a pathogenic mechanism for pulmonary hypertension in chronic lung disease". Circulation Research. 109 (5): 543–53. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.241299. PMC 3375237. PMID 21719760.

- ^ page 395, Biology, Fifth Edition, Campbell, 1999

- ^ Bernstein H, Payne CM, Bernstein C, Garewal H, Dvorak K (2008). Cancer and aging as consequences of un-repaired DNA damage. In: New Research on DNA Damages (Editors: Honoka Kimura and Aoi Suzuki) Nova Science Publishers, Inc., New York, Chapter 1, pp. 1–47. open access, but read only https://www.novapublishers.com/catalog/product_info.php?products_id=43247 Archived 2014-10-25 at the Wayback Machine ISBN 1604565810 ISBN 978-1604565812

- ^ a b c d e Swinnen E, Wanke V, Roosen J, Smets B, Dubouloz F, Pedruzzi I, Cameroni E, De Virgilio C, Winderickx J (April 2006). "Rim15 and the crossroads of nutrient signalling pathways in Saccharomyces cerevisiae". Cell Division. 1 (3): 3. doi:10.1186/1747-1028-1-3. PMC 1479807. PMID 16759348.

- ^ a b Sage, Julien (2004). "Cyclin C Makes an Entry into the Cell Cycle". Developmental Cell. 6 (5): 607–608. doi:10.1016/S1534-5807(04)00137-6. PMID 15130482.

- ^ a b Ren S, Rollins BJ (April 2004). "Cyclin C/cdk3 promotes Rb-dependent G0 exit". Cell. 117 (2): 239–51. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00300-9. PMID 15084261.