Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Gakhars

View on Wikipedia

| Gakhars | |

|---|---|

| Religions | |

| Languages | Pothwari |

| Country | |

| Region | Punjab |

| Ethnicity | Punjabi |

The Gakhar (Punjabi: گکھڑ, romanized: Gakkhaṛ) is a historical Punjabi tribe, originating in the Pothohar Plateau of Punjab, Pakistan. They predominantly adhere to Islam.[1][2][3][4]

History

[edit]In the Muslim historiography, the Gakhars have been frequently confused with the Khokhars, who inhabited the same region, and it has been challenging to separate the events of both tribes. Gakhars formed an important part of the army of Shāhis of Gandhāra. Around 30,000 Gakhars fought against Maḥmūd of Ghazna in 1008 CE near Peshawar but were defeated.[5] By the time of Sultan Muʿizz al-Dīn Muḥammad Ghūrī Gakhars had converted to Islam.[5]

In the following centuries, Gakhars engaged in a long-running struggle for sovereignty over the Salt Range with the neighbouring tribes:[6]

The history of this region (the Salt Range) from the thirteenth century onward had been a sickening record of wars between various dominant landowning and ruling clans of Punjabi Muslims including the Janjuas, Gakhars, Thathals and Bhattis for political ascendancy.[7]

For a period, Gakhars were superseded by the Khokhars who under their chieftain Jasrat gained control of most of upper Punjab in the 15th century. However, by the time of Mughal emperor Bābur's invasion of subcontinent, Gakhars had regained power. Under their chief Hātī Khān, Gakhars attacked Babūr in 1525 when he marched against the Delhi Sultanate. Babūr seized Gakhar fortress of Phaŕwāla and Hātī Khān fled, but when Hātī Khān offered his submission to Babūr and provided supplies for the Mughal army, he compensated Hātī Khān well and conferred on him the title of Sultan.[5]

During the reign of Humāyūn, Sulṭān Sārang Khān gained much prominence. He refused to acknowledge Shēr Shāh Sūr as new emperor when the latter defeated Humāyūn, as a result Shēr Shāh led an expedition against Sārang Khān who was defeated and executed. His tomb is in Rawāt.[5]

Sārang Khān's brother, Ādam Khān succeeded him. In 1552, Humāyūn's rebel brother prince Kamrān sought shelter with Ādam Khān but he was betrayed and given up to Humāyūn, who rewarded Ādam Khān with the insignia of nobility for the treachery.[5]

In 1555, Ādam Khān was defeated and killed by his nephew Kamāl Khān, a son of Sārang Khān, possibly on the instigation by emperor Akbar to strengthen his hold over the Gakhars. Further a daughter of Kamāl Khān's brother, Sayd Khān was married to prince Salim.[5]

In 1738 Nader Shah invaded India, during this invasion the city of Gujrat was sacked and after Shah returned to Persia, the city was then taken over by Gakhar chief Mukarrab Khan.[8]

M. A. Sherring writing in 1879 described the Gakhars as an "aboriginal race subdued by Pathan invaders from beyond the Indus." Sherring writing of Hazara District wrote that "they are found to the south of the district. The Gukkur chief resides at Khanpoor. Formerly, the Gukkurs, secure in their mountain fastnesses, set the rulers of the Punjab at defiance, and even exacted blackmail from them." In Hazara the Gakhars were neighbours of the Dhund tribe who similarly seemed to be able to challenge outsiders.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2025) |

See also

[edit]- Sarang Gakhar, Chief of Gakhars

- List of Punjabi tribes

- Gakhar Mandi

References

[edit]- ^ Van Donzel, E. J., ed. (1994). Islamic Desk Reference. BRILL. p. 106. ISBN 978-9-00409-738-4.

- ^ Gandhi, Surjit Singh (2007). History of Sikh Gurus Retold: 1469-1606 C.E. Atlantic Publishers. p. 3. ISBN 978-81-269-0857-8.

The story of most of the Gakhars is that they conquered Kashmir and ruled in that region for many generations but were eventually driven back to Kabul whence they entered the Punjab. They professed the Hindu faith and were converted to Islam, probably after the Ghori rule.

- ^ Singha, Atara (1976). Socio-cultural Impact of Islam on India. Panjab University. p. 46.

After this period, we do not hear of any Hindu Gakhars or Khokhars, for during the next two or three centuries they had all come to accept Islam.

- ^ Chandra, Satish (2006). Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals. Vol. 2 (Revised, 2nd ed.). Har-Anand Publications. p. 45. ISBN 978-8-12411-066-9.

- ^ a b c d e f Ansari 2012.

- ^ Journal of the Pakistan Historical Society, Volume 54, Issues 1–2. Pakistan Historical Society. 2006.

- ^ Bakshi, S. R. (1995). Advanced History of Medieval India. Anmol Publications. p. 142. ISBN 978-8-17488-028-4.[permanent dead link]

- ^ [https://punjab.global.ucsb.edu/sites/default/files/sitefiles/journals/volume20/12-Reeta%20Sharma%2020.pdf Urban Patterns in the Punjab Region since Protohistoric Times]

Bibliography

[edit]- Ansari, A.S. Bazmee (2012). "Gakkhaŕ". The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition (12 vols.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_2415.

Further reading

[edit]- Khan, Chaudhary Muhammad Afzal (1357 H). Rajpūt Gotaīñ (in Urdu) – via Rekhta.org.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

Gakhars

View on GrokipediaOrigins and Etymology

Claimed Ancestral Lineages

The Gakhars have advanced several competing ancestral claims, primarily documented in tribal genealogies and later historical accounts such as the Kaygawharnāma attributed to Rāyzāda Dunīchand Bālī and the chronicles of Muhammad Qasim Firishta completed in 1606 CE.[4][3] One prominent narrative traces their origins to Sassanian Persian nobility who, following defeats or migrations, retreated beyond the empire's northeastern frontiers into the Punjab region around the 7th century CE, adopting the title "Kay" or "Kayani" from ancient Persian royal traditions associated with the semi-mythical Kayani dynasty.[3][5] This Persian descent is invoked to underscore an aristocratic heritage, with Gakhar chieftains styling themselves as Kayani to evoke continuity with pre-Islamic Iranian elites.[6] Post-conversion Islamic genealogies extend these claims further, linking Gakhar lineages to biblical and prophetic figures, including descent from Hazrat Adam through intermediaries like Hazrat Sheesh (Seth) and subsequent Persian kings, as preserved in family records such as those of the Dhargloon Gakhars' Shagra-nasal branch.[7] These elaborations, often recorded in the medieval and early modern periods, integrate Quranic prophetic chains to elevate tribal status within Muslim society, portraying the Gakhars as inheritors of divine favor alongside temporal sovereignty.[8] Contrasting indigenous narratives, particularly in Firishta's accounts, depict the Gakhars as a pre-Islamic Kshatriya warrior clan native to northern India, who mounted resistance against Mahmud of Ghazni's invasions in the early 11th century CE, allying with figures like Anandapala, son of the Hindu Shahi ruler Jayapala.[3][4] This portrayal frames them as autochthonous defenders of the Punjab frontiers rather than exogenous migrants, emphasizing martial prowess against Central Asian incursions. Such genealogies, while central to Gakhar identity and prestige, lack corroboration from contemporary pre-Islamic artifacts, inscriptions, or archaeological evidence supporting foreign noble descent; surviving Gakhar monuments, like those at Pharwala Fort, date to the Islamic era and reflect local adaptations rather than Persian imports.[9] The Encyclopaedia of Islam suggests the Gakhars more plausibly emerged from Central Asian invading groups between the Kushan (1st-3rd centuries CE) and Ephthalite (5th-6th centuries CE) periods, but deems specific royal linkages inconclusive absent primary sources.[10] These claims thus appear to function as retrospective constructs for legitimizing authority in competitive tribal and imperial contexts, prioritizing symbolic elevation over verifiable historical continuity.[11]Linguistic and Archaeological Evidence

The name "Gakhar" (or Ghakkar) first appears in 11th-century Persian chronicles documenting interactions in the Punjab frontier, such as accounts from the Ghaznavid era, where it denotes local hill tribes resisting invasions without any indicated foreign linguistic derivation.[10] These records, including those linked to figures like Al-Biruni's contemporaries, treat the term as an indigenous designation for groups in the Pothohar region, consistent with Punjabi dialects featuring guttural consonants and references to rugged terrain, rather than Persian or Turkic roots.[1] Etymological analyses by historians, such as those positing an Indian origin for the word, align with this, rejecting claims of exotic provenance due to the absence of corroborative philological evidence in primary sources.[5] Archaeological surveys in the Pothohar Plateau, encompassing core Gakhar territories, reveal stratified settlements with pottery, lithic tools, and megalithic structures dating to pre-1000 CE periods, exhibiting continuity with broader Indus Valley peripheral cultures and local Iron Age traditions rather than abrupt overlays from distant migrations.[12] Sites like those near Taxila and Soan Valley yield artifacts from the Neolithic (circa 3360 BCE) through Kushan eras, indicating indigenous tribal habitation patterns marked by hill fortifications and agrarian adaptations, which prefigure Gakhar-era constructions without evidence of a sudden non-local influx. Gakhar-specific remains, primarily 11th-16th century forts (e.g., Rawat and Pharwala) and tombs built from local stone, overlay these older layers, suggesting the tribe consolidated power amid existing regional frameworks rather than introducing novel architectural or material signatures.[13][14] Regional genetic studies of Punjab tribes, including those in Potohar, document Y-chromosome haplogroups (e.g., R1a and L) predominant in South Asian populations with variable steppe-derived admixture akin to Jat and other local groups, but no elevated frequencies of haplogroups uniquely tied to Persian or Scythian elites that would support non-indigenous dominance.[15] This admixture pattern reflects ancient regional gene flow rather than a distinct Gakhar founder effect, underscoring material and biological continuity with Punjab's pre-Islamic tribal substrate.[16]Historical Territories

Core Regions and Fortifications

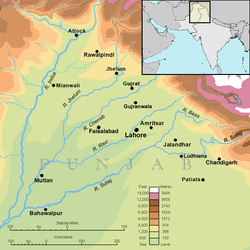

The Gakhars' core homeland encompassed the Pothohar Plateau in northern Punjab, Pakistan, spanning hilly terrains around modern-day Rawalpindi, Jhelum, and Islamabad districts. This elevated region, with its strategic ravines and heights averaging 300-600 meters, facilitated defensive guerrilla tactics against larger invading forces throughout history.[14][17] To fortify their domains, the Gakhars erected multiple stone-walled strongholds leveraging the natural topography for enhanced defensibility. Pharwala Fort, perched on a hill near Hasan Abdal, functioned as a key Gakhar bastion until its seizure by Babur's forces in 1515, demonstrating the tribe's reliance on elevated positions for prolonged resistance.[18][19] Rawat Fort, initially a 16th-century caravanserai along the Grand Trunk Road, was reinforced by Gakhar chiefs like Sultan Sarang Khan to counter threats, including Sher Shah Suri's campaigns, with its compact design incorporating defensive walls and watchtowers suited to the plateau's invasion routes.[20][17] Rohtas Fort, constructed by Sher Shah Suri from 1541 to 1548 near Jhelum specifically to suppress Gakhar rebellions, featured massive sandstone battlements and aqueducts for sustained sieges, indirectly highlighting the tribe's effective hill-based fortifications that necessitated such countermeasures.[21][22][23] Post-1849 British annexation of Punjab, colonial records noted the Gakhars' prior control over extensive village networks in Pothohar, reflecting the scale of their fortified territorial core prior to Sikh and British dominance.[24][25]Expansion and Influence Areas

The Gakhars maintained peripheral influence in Mirpur district of present-day Azad Jammu and Kashmir through kinship networks with local clans, fostering cultural and marital ties that extended their reach without imposing direct administrative control or military occupation.[3] Similar connections linked them to communities in Gilgit-Baltistan, where shared ancestral claims and migrations sustained loose affiliations, though these areas remained under independent local rulers rather than Gakhar dominion.[5] These extensions relied on opportunistic family alliances rather than sustained conquest, reflecting the tribe's strategy of leveraging relational bonds in rugged terrains beyond their Pothohar heartland. In the Northwest Frontier, encompassing parts of present-day Khyber Pakhtunkhwa including Chitral, Gakhar elements pursued trade routes and raiding expeditions for high-quality horses and timber resources vital to their cavalry-based warfare and economy.[26] Khanpur served as a key outpost facilitating such activities, acting as a defensive hub that projected influence into the Hazara-Taxila belt and adjacent frontier zones through semi-autonomous outposts and tribute arrangements with neighboring hill tribes.[26] Geographic constraints defined the outer limits of Gakhar sway, as stronger imperial powers hemmed in their autonomy; the Delhi Sultanate and Mughal Empire enforced boundaries via tribute demands and selective alliances, preventing wholesale expansion into adjacent lowlands or passes.[5] Accounts by the historian Ferishta, though sometimes conflating Gakhars with the distinct Khokhar tribe, underscore this containment, portraying their holdings as fragmented principalities vulnerable to central overlords' interventions.[5] Sikh chronicles further delineate these peripheries, recording Gakhar control as circumscribed to highland pockets, checked by Punjab's expanding misls through raids and fort sieges that precluded further outreach.[1]Political and Military History

Pre-Islamic and Early Islamic Periods

The Gakhars, a warlike Punjabi tribe centered in the Pothohar Plateau, adhered to Hinduism prior to the advent of Muslim rule in the region.[27] Their early history is obscure, with limited archaeological or epigraphic evidence predating Islamic chronicles, though they inhabited rugged terrains conducive to defensive warfare against lowland invaders.[28] During Mahmud of Ghazni's raids into Punjab in the early 11th century, the Gakhars emerged as formidable opponents. The Persian chronicler Muhammad Qasim Ferishta records that they mobilized a cavalry force of approximately 30,000 horsemen to contest Ghaznavid advances, a figure probable embellished to underscore their ferocity.[29] In engagements circa 1007–1008 CE, including near the Chach region, Gakhar fighters repelled Mahmud's light infantry despite his direct command, inflicting heavy casualties—estimated at up to 5,000 in one ambush—and nearly compelling a Ghaznavid retreat, thereby disrupting plunder routes.[1] [3] This defiance, often in alliance with Hindu Shahi forces like those of Anandapala, highlighted the tribe's tactical reliance on archery and guerrilla ambushes in defiles, sustaining their autonomy amid repeated incursions.[29] In the transition to Islamic dominance under the Ghurids by the late 12th century, the Gakhars encountered coercive assimilation. Captives from conflicts with Muhammad Ghori around 1192–1206 CE, including Gakhars alongside Khokhars, underwent forced conversions as a condition of survival or release, marking the onset of Islamization in the early 12th century.[30] Sufi missionaries further facilitated voluntary shifts among elites, though mass adherence lagged until Sultanate consolidation.[27] By the early 13th century, with the Delhi Sultanate's establishment in 1206, converted Gakhar chiefs pragmatically pledged nominal fealty to avert subjugation, preserving de facto independence through fortified redoubts and intermittent revolts against overreach, thus navigating the era's invasions without wholesale annihilation.[30]Relations with Delhi Sultanate and Mughals

The Gakhars maintained a pragmatic relationship with the Delhi Sultanate, characterized by intermittent tribute payments and localized rebellions aimed at preserving autonomy in the rugged Potohar plateau. In the early 13th century, they resisted Qutbuddin Aibak's forces following Muhammad of Ghor's invasion, rebelling in 1205 amid broader tribal unrest in Punjab.[1] By the mid-13th century, under sultans like Balban (r. 1266–1287), the Gakhars were compelled to submit tribute as part of broader campaigns to stabilize Punjab frontiers against Mongol incursions, though they retained de facto control over hill forts like Pharwala.[31] This fealty was not ideological but a calculated exchange for security and recognition of their territorial holdings, with rebellions flaring when central authority weakened, such as during succession crises.[32] The advent of Mughal rule marked a pivotal shift, beginning with initial resistance followed by strategic alignment. In March 1519, Hati Khan Gakhar, chief of the tribe, opposed Babur's invasion by fortifying Pharwala and allying with the Lodi Sultanate; Babur's forces captured the fort after a siege, prompting Hati's submission and the Gakhars' integration as frontier auxiliaries.[33] Hati's death by poisoning in 1525 led his cousin Sultan Sarang Khan to reaffirm loyalty, receiving Potohar jagirs in return and participating in Mughal campaigns against rivals like Rana Sanga.[34] This alliance endured through Humayun's reign but fractured under Sher Shah Suri (r. 1540–1545), who viewed the Gakhars' pro-Mughal stance as a threat; Sarang Khan rebelled, prompting Sher Shah to ravage Gakhar lands, enslave thousands, and construct Rohtas Fort in 1541–1543 as a garrison to subdue them.[23][35] Post-Suri, the Gakhars reverted to Mughal fidelity, providing military service in exchange for jagirdari rights and autonomy. Leaders like Kamal Khan and later Muqarrab Khan served Akbar, Jahangir, and Aurangzeb, suppressing local revolts and defending northwestern passes, with alliances driven by mutual interest in territorial stability rather than unwavering fealty.[36] By the late 16th century, their role as reliable zamindars solidified Mughal control over Punjab's highlands, though underlying tensions persisted over revenue demands.[37]18th-19th Century Decline

The Gakhar chieftaincy faced initial erosion during the 1739 invasion by Nader Shah of Persia, when chief Muqarrab Khan submitted to the conqueror, aligning with external forces as Mughal imperial control fragmented in northern Punjab.[38] This opportunistic accommodation preserved short-term survival but contributed to the broader destabilization of regional Muslim elites reliant on Delhi's patronage, exposing Gakhar territories in the Pothohar Plateau to subsequent power vacuums.[1] Sikh military expansion under misl confederacies intensified pressures in the late 18th century, with Gakhar forces defeated at Rawalpindi in 1765, marking the loss of key lowland holdings.[30] By 1810–1818, Maharaja Ranjit Singh's Sikh Empire systematically annexed remaining Gakhar towns and jagirs, confining the tribe to upland fastnesses and reducing their influence to peripheral hill domains amid the consolidation of Sikh suzerainty over Punjab plains.[1][39] Following the British annexation of Punjab after the Second Anglo-Sikh War in 1849, colonial administrators implemented jagir reforms that further marginalized Gakhar elites, converting hereditary land grants into cash pensions and proprietary rights into tenancies, effectively dismantling autonomous tribal governance structures.[40] These policies, aimed at centralizing revenue and loyalty, stripped the Gakhars of military and fiscal autonomy, relegating them from regional potentates to pensioned zamindars by the mid-19th century, with residual holdings vulnerable to post-1857 confiscations for perceived disloyalty during the Indian Rebellion.[40]Social Structure and Culture

Tribal Organization and Governance

The Gakhars maintained a feudal hierarchy centered on a paramount chief, titled Khan or Raja, who wielded authority over military campaigns, revenue collection, and territorial defense in the Pothohar region. Leadership was predominantly hereditary, transmitted patrilineally within ruling lineages such as the Sultan or Kayani branches, ensuring continuity amid alliances with imperial powers like the Mughals.[41][42] Internal power transitions occasionally involved selection among eligible kin to resolve disputes, as evidenced by rivalries between figures like Kamal Khan and Sultan Adam Gakhar in the 16th century, reflecting a blend of inheritance and pragmatic consensus to avert fragmentation.[float-right] Tribal cohesion relied on clan-based subdivisions, with sub-groups like the Gakhar Rajputs or Jats operating semi-autonomously under subordinate headmen who owed fealty to the chief, facilitating localized governance while upholding overarching loyalty.[44] Kinship networks were fortified through preferential endogamy within the tribe and inter-clan marriages, which secured political pacts and expanded influence without diluting core allegiances.[45] This structure emphasized martial readiness and territorial control, with the chief's court serving as the nexus for adjudication and mobilization, though chronicled revolts underscore the limits of centralized command in a decentralized tribal ethos.[46]Economy, Warfare, and Customs

The Gakhars sustained their livelihoods through subsistence agriculture and pastoralism in the rugged Pothohar plateau, cultivating staple crops like wheat in fertile valleys while rearing livestock such as goats and sheep adapted to the hilly tracts.[47] As semi-autonomous chieftains, they supplemented this with tribute extracted from subordinate villages and clans, a system that ensured economic viability amid frequent conflicts.[39] In warfare, the Gakhars emphasized defensive fortifications leveraging the plateau's natural barriers, constructing hilltop strongholds like Pharwala Fort, which Babur assaulted in March 1519 using escalade tactics to overcome its steep defenses held by Hati Khan Gakhar.[33] Mughal chronicles highlight their guerrilla-style resistance and alliances, including service in imperial campaigns, though they often rebelled against central authority, prompting retaliatory sieges by rulers like Sher Shah Suri, who built Rohtas Fort in 1541 specifically to subdue them. Tribal customs revolved around codes of honor stressing familial loyalty, vengeance, and martial prowess, yet pragmatic survival often led to documented betrayals and intra-clan rivalries. For instance, in 1555, Kamal Khan Gakhar defeated and captured his uncle Sultan Adam Khan Gakhar—ruler since 1546—to seize control of Pothohar territories, subordinating kinship ties to ambitions for Mughal favor under Akbar.[48] Such shifts in allegiance, including initial support for the Suris before pivoting to the Mughals, underscore a realist adaptation over rigid honor in the face of superior imperial power.[49]Religious Conversions and Identity

Prior to the 12th century, the Gakhars practiced Hinduism, encompassing polytheistic rituals and tribal customs typical of Rajput clans in the Punjab highlands.[30] Their religious shift to Islam commenced in the early 1200s amid the Ghurid conquests under Mu'izz al-Din Muhammad (r. 1173–1206), when captured Gakhar and allied Khokhar warriors faced coerced conversions as a condition of survival following defeats.[50] This initial elite-led adoption was pragmatic, driven by the need to forge alliances with incoming Muslim rulers to retain territorial control and avert annihilation, rather than widespread popular enforcement.[3] Subsequent generations solidified Islamic adherence through intermarriage with Sufi-influenced networks and service to sultanates, enabling the Gakhars to transition from resistors to semi-autonomous vassals under the Delhi Sultanate and later Mughals.[51] Historical accounts, such as those in Ferishta's 17th-century chronicle, portray this as a calculated retention of power, with chieftains like Bangash Khan credited as pivotal early converts who secured clan privileges.[3] Mass conversions among the populace followed elite precedents, incentivized by social emulation and exemptions from jizya tax, though resistance persisted in peripheral strongholds until the 14th century.[52] Post-conversion identity centered on Sunni Islam, with Gakhars distinguishing themselves as martial guardians of Islamic frontiers, yet traces of syncretism lingered in localized customs blending tribal veneration with Sufi piety—such as reverence for ancestral lineages framed within Islamic ethics—without overt polytheistic revival.[53] This hybridity reflected causal adaptations for cohesion in a multi-ethnic empire, prioritizing orthodoxy to access patronage while subtly preserving clan solidarity. Modern Gakhar descendants in Pakistan overwhelmingly identify as Sunni Muslims, with negligible Hindu remnants, underscoring the durability of the 13th-century pivot for socioeconomic integration.[54]Notable Gakhar Leaders

Early Chiefs and Warriors

In the early 11th century, Gakhar warriors mounted significant resistance against the Ghaznavid invasions led by Mahmud of Ghazni, allying with the Hindu Shahi ruler Anandapala following his father's defeat. Historical accounts describe these pagan Gakhars as providing substantial military support, including forces that harassed Ghaznavid troops during campaigns through the Punjab region after the capture of Ohind (Waihind), complicating Mahmud's advances despite his victories.[34] This early martial role established the Gakhars as formidable hill warriors in the Pothohar plateau, leveraging terrain for defensive actions against external aggressors. By the 15th century, Hati Khan (also known as Hathi or Hatti Khan) emerged as a prominent Gakhar chief, exemplifying the tribe's pattern of strategic submissions interspersed with revolts to maintain autonomy amid Delhi Sultanate influence. As ruler of territories around Pharwala Fort, which he renovated to bolster defenses, Hati Khan consolidated power through aggressive internal maneuvers, including the poisoning of his cousin Tatar Khan around 1519 to seize leadership and the subsequent arrest of Tatar's sons, Sarang and Adam Khan.[35] [14] Hati Khan's tenure highlighted Gakhar resistance to emerging threats; in 1519, he initially opposed Babur's invading forces at Pharwala, where Gakhar defenders inflicted casualties before Hati escaped, though he later submitted and allied with Babur against the Lodi dynasty to secure his position. This pragmatic shift from revolt to alliance reflected the tribe's adaptive warfare, but internal vendettas persisted, culminating in Hati's poisoning by Sarang Khan in 1524 as retribution.[35] Such episodes underscored the Gakhars' pre-Mughal reputation for fierce, opportunistic militancy in the Salt Range and Jhelum areas, often resisting full subjugation while exploiting divisions among sultanate rivals.[14]Mughal-Era Rulers

Sultan Sarang Khan Gakhar (died 1546), chief of the Gakhars, was appointed ruler of the Pothohar Plateau by Mughal Emperor Babur around 1520 in recognition of his submission and loyalty following initial resistance.[14] He led military campaigns against tribal rivals and served as a Mughal general, notably resisting the forces of Sher Shah Suri during the latter's brief overthrow of Mughal rule in the 1540s, which demonstrated the Gakhars' strategic alignment with imperial authority to maintain regional control.[49] Sarang Khan also commissioned fortifications and mosques, such as the one at Rawat Fort, underscoring his role in consolidating Gakhar power under Mughal suzerainty.[37] In the late Mughal period, as central authority fragmented, Sultan Muqarrab Khan (reigned circa 1738–1769) emerged as a pivotal Gakhar leader, balancing allegiance to the declining empire with opportunistic expansions. He participated in the Battle of Karnal in 1739 alongside Nader Shah's invading forces against Mughal Emperor Muhammad Shah, which facilitated Persian dominance and indirectly bolstered local autonomy for compliant chiefs like Muqarrab.[55] Following this, Muqarrab Khan conquered the cities of Gujrat and Jhelum around 1740, extending Gakhar influence in the Chaj Doab amid the power vacuum.[1] He later pledged loyalty to Ahmad Shah Durrani, leveraging these alliances to defend Pothohar territories against Afghan incursions and emerging Sikh pressures until his death.[56]Legacy and Modern Descendants

Architectural and Cultural Heritage

The Pharwala Fort, constructed around 1005 CE by Sultan Kaigohar Gakhar, represents the earliest and most prominent example of Gakhar defensive architecture in the Potohar plateau of Punjab, Pakistan. Perched on a rocky hill overlooking the Soan River, the fort's multi-tiered stone walls, bastions, and gateways demonstrate adaptive engineering for rugged terrain, prioritizing elevation for surveillance and water cisterns for siege endurance.[13] Later renovations by Hathi Khan Gakhar in the 15th century enhanced its fortifications, incorporating arched entrances and extended ramparts amid alliances and conflicts with regional powers.[57] Religious structures built by Gakhar patrons further illustrate their patronage of Indo-Persianate influences blended with local stone masonry. The Mai Qamro Mosque, erected in the early 16th century by Mai Qamro—wife of a Gakhar chief—near Pharwala Fort, features a tri-domed prayer hall with mihrab niches and minarets, marking it as the oldest surviving mosque in the Islamabad area.[18] This design, echoed in the three-domed mosque within Rawat Fort (built circa 1540 by Sultan Sarang Khan Gakhar), reflects modular construction using lime mortar and dressed stones, adapted for seismic-prone highlands while facilitating congregational worship.[13][20] Additional Gakhar-commissioned sites, such as the tomb of Muqarab Khan in Bagh Jogian and the Rani Mongho Tomb in Kallar Sayedan (both 16th-17th centuries), employ octagonal plans and decorative calligraphy, underscoring a shift toward funerary monuments post-Mughal integration.[9][58] These structures, concentrated in Potohar villages, highlight Gakhar rulers' role in disseminating brick-and-stone techniques from 1002 to 1765 CE, though many remain unrestored.[14] Preservation efforts by Pakistan's Department of Archaeology have targeted sites like Rawat Fort, with partial restorations in 2025 addressing erosion, yet widespread neglect persists due to urbanization and inadequate funding, leaving forts like Pharwala vulnerable to structural decay.[20][18] Independent surveys note that over half of documented Gakhar monuments in Punjab exhibit crumbling facades and encroaching vegetation, underscoring risks to empirical study of their load-bearing innovations.[14][13]Contemporary Distribution and Role in Pakistan

The Gakhars, also known as Gakkhars, are predominantly distributed across the Pothohar Plateau in northern Punjab province, with concentrations in the districts of Rawalpindi, Jhelum, and Mirpur.[3] [59] Smaller numbers reside in adjacent areas of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.[59] Pakistan's 2017 census does not provide tribe-specific breakdowns, but estimates place the Gakhar population at approximately 64,000, reflecting their status as a localized ethnic group without significant diaspora abroad.[59] In contemporary Pakistan, Gakhars are fully integrated into national society as Sunni Muslims, engaging in urban professions, agriculture, and service in the military and bureaucracy on an individual basis rather than as a unified tribal entity exerting bloc influence in politics or governance.[59] [3] Community members express pride in their historical warrior heritage and fort-building legacy, such as Rawat Fort, yet demonstrate assimilation into broader Punjabi-Pakistani identity without advocating separatist or autonomous claims.[59] This contrasts with more fragmented tribal dynamics elsewhere, as Gakhars lack formalized tribal councils or land-based separatism in the post-colonial era.References

- ./assets/Kamal_Khan_Ghakkar_defeats_Sultan_Adam_Ghakkar.jpg

- https://handwiki.org/wiki/History:Gakhar_kingdom