Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Nader Shah

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

Nader Shah Afshar[b] (born Nader Qoli;[9] Persian: نادرشاه افشار; 6 August 1698 or 22 October 1688[a] – 20 June 1747) was the founder of the Afsharid dynasty of Iran and one of the most powerful rulers in Iranian history, ruling as the emperor of Iran (Persia) from 1736 to 1747, when he was assassinated during a rebellion. He fought numerous campaigns throughout the Middle East, the Caucasus, Central Asia, and South Asia, emerging victorious from the battles of Herat, Mihmandust, Murche-Khort, Kirkuk, Yeghevārd, Khyber Pass, Karnal, and Kars. Nader belonged to the Turkoman Afshars, one of the seven Qizilbash tribes that helped the Safavid dynasty establish their power in Iran.

Nader rose to power during a period of chaos in Iran after a rebellion by the Hotaki Afghans had overthrown the weak emperor Soltan Hoseyn (r. 1694–1722), while the arch-enemy of the Safavids, the Ottoman Empire, as well as the Russian Empire, had seized Iranian territory for themselves. Nader reunited the Iranian realm and removed the invaders. He became so powerful that he decided to depose the last members of the Safavid dynasty, which had ruled Iran for over 200 years, and declared himself Shah in 1736. His numerous campaigns created a great empire that, at its maximum extent, briefly encompassed all or part of modern-day Afghanistan, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Georgia, India, Iran, Iraq, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Oman, Pakistan, Uzbekistan, the North Caucasus, and the Persian Gulf, but his military spending had a ruinous effect on the Iranian economy.[1]

Nader Shah has been described as "the last great Asiatic military conqueror".[10] He idolized Genghis Khan and Timur, the previous conquerors from Central Asia. He imitated their military prowess and, especially later in his reign, their cruelty. His victories during his campaigns briefly made him West Asia's most powerful sovereign, ruling over what was arguably the most powerful empire in the world.[11]: 84

Following his assassination in 1747, his empire quickly disintegrated, and Iran fell into a civil war. His grandson Shahrokh Shah was the last of his dynasty to rule, ultimately being deposed in 1796 by Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar, who crowned himself ruler of Qajar Iran the same year.[12]

Background

[edit]Nader belonged to the Turkoman Afshar tribe, which was one of the seven tribes[c] of the Qizilbash who helped the Safavid dynasty establish their power in Iran.[13][14] The Afshar tribe had originally lived in the Turkestan region, but during the 13th century they moved to the Azerbaijan region in northwestern Iran as a result of the expansion of the Mongol Empire.[15]

Nader was from the semi-nomadic Qirqlu clan of the Afshars, which lived in the Khorasan region of northeastern Iran. They had either settled there during the reign of the first Safavid emperor, Ismail I (r. 1501–1524), or had been resettled by Shah Abbas I (r. 1588–1629) to fend off Uzbek attacks. Regardless, the Afshars' migration to Khorasan was already taking place by start of the 16th century.[16][17]

The Afshar dialect is categorized either as a dialect of the Southern Oghuz group or a dialect of the Azerbaijani.[14] As he was growing up, he must have swiftly learned Persian, which was the language of the cities and high culture. However, unless he was speaking to someone who spoke only Persian, he always preferred to communicate in Turkic.[18] His knowledge of Arabic is not documented, but it seems doubtful given his lack of interest in literature and theology.[19] Nader is known to have acquired reading and writing skills at some point in his life, probably later on.[18]

Approximately three million people or more were nomadic or semi-nomadic pastoralists in Iran in the beginning of the 18th century, accounting for one-third of the country's population. Strong ties of kinship as well as customs of helping each other out with fights and finances kept their tribal groups united. Despite being partially or fully absorbed into the more urbanized Persian culture, many of them nevertheless identified culturally with the Turco-Mongol heritage that had been passed down from the era of Timur and Genghis Khan. The settled population was seen by the semi-nomads and nomads as inferior. Nader was part of this heritage, which the British academic Michael Axworthy calls "paradoxical".[18]

Early life

[edit]Nader was born in the fortress of Dastgerd[20] in the northern valleys of Khorasan, a province in the northeast of the Iranian Empire.[21] His father, Emam Qoli, was a herdsman who may also have been a coatmaker.[4] His family lived a nomadic way of life. Nader was a long-waited son in his family.[22]

At the age of 13, Nader lost his father and had to find a way to support himself and his mother. He had no source of income other than the sticks he gathered for firewood, which he transported to the market. Many years later, when he was returning in triumph from his conquest of Delhi, he led the army to his birthplace and made a speech to his generals about his early life of deprivation. He said, "You now see, to what a height it has pleased the Almighty to exalt me; from this you should learn not to despise men of low estate." Nader's early experiences did not, however, make him particularly compassionate toward the poor. Throughout his career, he was only interested in his own advancement. Legend has it that in 1704, when he was about 17, a band of marauding Uzbeks invaded the province of Khorasan, where Nader lived with his mother. They killed many peasants. Nader and his mother were among those who were carried off into slavery. His mother died in captivity. According to another story, Nader managed to convince Turkmens by promising help in the future. Nader returned to the province of Khorasan in 1708.[23]

At the age of 15, he enlisted as a musketeer for a governor. He rose through the ranks and became the governor's right-hand man.[24]

Fall of the Safavid dynasty

[edit]Nader grew up during the final years of the Safavid dynasty, which had ruled Iran since 1502. At its peak, under such figures as Abbas the Great, Safavid Iran had been a powerful empire, but by the early 18th century the state was in serious decline, and the reigning shah, Soltan Hoseyn, was a weak ruler. When Soltan Husayn attempted to quell a rebellion by the Ghilzai Afghans in Kandahar, the governor he sent (Gurgin Khan) was killed. Under their leader Mahmud Hotaki, the rebellious Afghans moved westwards against the shah himself, and in 1722 they defeated a force at the Battle of Gulnabad and then besieged the capital, Isfahan.[25] After the Shah failed to escape or to rally a relief force elsewhere, the city was starved into submission and Soltan Husayn abdicated, handing power to Mahmud. In Khorasan, Nader at first submitted to the local Afghan governor of Mashhad, Malek Mahmud, but then rebelled and built up his own small army. Soltan Husayn's son had declared himself Shah Tahmasp II, but found little support and fled to the Qajar tribe, who offered to back him. Meanwhile, Iran's imperial neighboring rivals, the Ottomans and the Russians, took advantage of the chaos in the country to seize and divide territory for themselves.[26] In 1722, Russia, led by Peter the Great and further aided by some of the most notable Caucasian regents of the disintegrating Safavid Empire, such as Vakhtang VI, launched the Russo-Iranian War (1722–1723) in which Russia captured swaths of Iran's territories in the North Caucasus, South Caucasus, as well as in northern mainland Iran. This included mainly, but was not limited to, the losses of Dagestan (including its principal city of Derbent), Baku, Gilan, Mazandaran, and Astrabad. The regions to the west of that, mainly Iranian territories in Georgia, Iranian Azerbaijan, and Armenia, were taken by the Ottomans. The newly gained Russian and Turkish possessions were confirmed and further divided amongst themselves in the Treaty of Constantinople (1724).[27] During the chaos, Nader cut a deal with Mahmud Hotaki to rule Kalat in the north of Iran. However, when Mahmud Hotaki began minting coins in his name and asked for everyone's allegiance, Nader refused.[24][page needed]

Fall of the Hotaki dynasty

[edit]

Tahmasp and the Qajar leader Fath Ali Khan (the ancestor of Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar) contacted Nader and asked him to join their cause and drive the Ghilzai Afghans out of Khorasan. He agreed and thus became a figure of national importance. When Nader discovered that Fath Ali Khan was in treacherous correspondence with Malek Mahmud and revealed this to the shah, Tahmasp executed him and made Nader the chief of his army instead. Nader subsequently took on the title Tahmasp Qoli (Servant of Tahmasp). In late 1726, Nader recaptured Mashhad.[28]

Nader chose not to march directly on Isfahan. First, in May 1729, he defeated the Abdali Afghans near Herat. Many of the Abdali Afghans subsequently joined his army. The new shah of the Ghilzai Afghans, Ashraf, decided to move against Nader but in September 1729, Nader defeated him at the Battle of Damghan and again decisively in November at Murchakhort. Ashraf fled, and Nader finally entered Isfahan, handing it over to Tahmasp in December. The citizens' rejoicing was cut short when Nader plundered them to pay his army. Tahmasp made Nader governor over many eastern provinces, including his native Khorasan, and Tahmasp's sister was given in marriage to Nader's son. Nader pursued and defeated Ashraf, who was murdered by his own followers.[29] In 1738 Nader Shah besieged and destroyed the last Hotaki seat of power at Kandahar. He built a new city near Kandahar, which he named "Naderabad".[1]

First Ottoman campaign and the reconquest of the Caucasus

[edit]

In the spring of 1730, Nader attacked Iran's archrival the Ottomans and regained most of the territory lost during the recent chaos. At the same time, the Abdali Afghans rebelled and besieged Mashhad, forcing Nader to suspend his campaign and save his brother, Ebrahim. It took Nader fourteen months to crush this uprising.[30]

Relations between Nader and the Shah had declined as the latter grew jealous of his general's military successes. While Nader was absent in the east, Tahmasp tried to assert himself by launching a foolhardy campaign to recapture Yerevan. He ended up losing all of Nader's recent gains to the Ottomans and signed a treaty ceding Georgia and Armenia in exchange for Tabriz.[31] Nader, furious, saw that the moment had come to remove Tahmasp from power. He denounced the treaty, seeking popular support for a war against the Ottomans. In Isfahan, Nader got Tahmasp drunk then showed him to the courtiers, asking if a man in such a state was fit to rule. In 1732 he forced Tahmasp to abdicate in favour of the Shah's baby son, Abbas III, to whom Nader became regent.[32]

Nader decided, as he continued the 1730–1735 war, that he could win back the territory in Armenia and Georgia by seizing Ottoman Baghdad and then offering it in exchange for the lost provinces, but his plan went badly amiss when his army was routed by the Ottoman general Topal Osman Pasha near the city in 1733.[33] This was the only time that he was ever defeated in battle. Nader decided he needed to regain the initiative as soon as possible to save his position because revolts were already breaking out in Iran. He faced Topal again with a larger force and defeated and killed him. He then besieged Baghdad, as well as Ganja in the northern provinces, achieving an alliance with Russia against the Ottomans. Nader scored a great victory over a superior Ottoman force at Baghavard, and by the summer of 1735, Iranian Armenia and Georgia were his again. In March 1735, he signed a treaty with the Russians in Ganja by which the latter agreed to withdraw all of their troops from Iranian territory[34][35] (those which had not already been ceded back by the 1732 Treaty of Resht), resulting in the reestablishment of Iranian rule over all of the Caucasus and northern mainland Iran.

Shah of Iran

[edit]Nader suggested to his closest intimates, after a great hunting party on the Moghan plain (presently split between Azerbaijan and Iran), that he should be proclaimed the new king (shah) in place of the young Abbas III.[36] This small group of Nader's close friends included Tahmasp Khan Jalayer and Hasan-Ali Beg Bestami.[36] The group made no objections, but Hasan-Ali stayed silent.[36] When Nader asked Hasan-Ali why he remained silent, he replied that the best thing for Nader to do would be to assemble to all the most prominent men of the state in order to receive their agreement in "a signed and sealed document of consent".[36] Nader approved of this proposal, and the writers of the chancellery, which included the court historian Mirza Mehdi Khan Astarabadi, were instructed to sending out orders to the military leaders, clergy and nobility of the nation to summon at the Moghan plain.[36] The summonses for the people to attend had gone out in November 1735, and they began arriving in January 1736.[37] That same month, Nader held a qoroltai (a grand meeting in the tradition of Genghis Khan and Timur) on the Moghan plain. The Moghan plain was specifically chosen for its size and "abundance of fodder".[38] Everyone agreed to the proposal of Nader becoming the new king, many—if not most—enthusiastically, the rest fearing Nader's anger if they showed support for the deposed Safavids. Nader was crowned Shah of Iran on 8 March 1736, a date his astrologers had chosen as being especially favorable,[39] in attendance of an "exceptionally large assembly" composed of the nobility and military and religious elite of the nation, as well as the Ottoman ambassador Ali Pasha.[40]

He cut a deal with notables and the clergy that he would only assume the position of Shah if they promised to refrain from cursing Omar and Uthman, avoid beating themselves to draw blood at the Ashura festival, accept Sunni practices as legitimate, and to obey Nader's children and relatives after his death, thereby setting up a dynasty in his name. He was effectively realigning Persia with Sunni Islam. The notables accepted.[41] As was traditional for the ruler in Muslim nations, Nader's name was read in the Friday prayers and appeared on the coins from this point on. A new royal seal was also created, which said the following: "Since the jewel of State and Religion had vanished from its place God reinstated it in the name of the Iranian Nader".[42]

Religious policy

[edit]

The Safavids had forced Shia Islam as the state religion of Iran. Nader may have been brought up as a Shiite on the basis of his name and background[5] but later replaced Shia law with a version that was more sympathetic and compatible with Sunni law he called the "Ja'fari school" in an effort to disassociate radical Shia Islam from the state, in part to please his supporters and also to improve relationships with other Sunni powers[43] as he gained power and began to push into the Ottoman Empire. He believed that Safavid Shia Islam had intensified the conflict with the Sunni Ottoman Empire. His army was a mix of Shia and Sunni Muslims (with a notable minority of Christians and Kurds) and included his own Qizilbash as well as Uzbeks, Afghans, Christian Georgians and Armenians,[44][45] and others. He wanted Iran to adopt a form of religion that would be more acceptable to Sunni Muslims and suggested that Iran adopt a form of Shia Islam he called "Ja'fari", in honour of the sixth Shia imam Ja'far al-Sadiq. He banned certain Shia practices which were particularly offensive to Sunni Muslims, such as the cursing of the first three caliphs of Islam. Personally, Nader is said to have been indifferent towards religion and the French Jesuit who served as his personal physician reported that it was difficult to know which religion he followed and that many who knew him best said that he had none.[46] Nader hoped that "Ja'farism" would be accepted as a fifth school (madhhab) of Sunni Islam and that the Ottomans would allow its adherents to go on the hajj, or pilgrimage, to Mecca, which was within their territory. In the subsequent peace negotiations, the Ottomans refused to acknowledge Ja'farism as a fifth mazhab but they did allow Iranian pilgrims to go on the hajj.[47] Nader was interested in gaining rights for Iranians to go on the hajj in part because of revenues from the pilgrimage trade.[1] Nader's other primary aim in his religious reforms was to weaken the Safavids further since Shia Islam had always been a major element in support for the dynasty. He had a Shia mullah of Iran strangled after he was heard expressing support for the Safavids. Among his reforms was the introduction of what came to be known as the kolah-e Naderi. This was a hat with four peaks which symbolised the first four caliphs of Islam.[1] Alternatively, it has also been recorded that the four peaks symbolised the territories of Persia, India, Turkestan, and Khwarezm.[48]

In 1741, eight Muslim scholars and three European and five Armenian priests translated the Koran and the Gospels[clarification needed]. The commission was supervised by Mīrzā Moḥammad Mahdī Khan Monšī, the court historiographer and author of the Tarikh-e-Jahangoshay-e-Naderi (History of Nader Shah's Wars). Finished translations were presented to Nader Shah in Qazvīn in June 1741, who, however, was not impressed.[citation needed]

Nader diverted money going to Shia mullahs and redirected it to his army instead.[24][page needed]

Invasion of India

[edit]

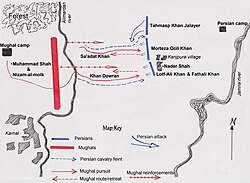

In 1738, Nader Shah conquered Kandahar, the last outpost of the Hotaki dynasty. His thoughts now turned to the Mughal Empire of India. This once powerful Muslim state to the east was falling apart as the nobles became increasingly disobedient and local opponents such as the Sikhs and Hindu Marathas of the Maratha Empire were expanding upon its territory. Its ruler Muhammad Shah was powerless to reverse this disintegration. Nader asked for the Afghan rebels to be handed over, but the Mughal emperor refused. Nader used the pretext of his Afghan enemies taking refuge in India to cross the border and invade the militarily weak but still extremely wealthy eastern empire,[49] and in a brilliant campaign against the governor of Peshawar he took a small contingent of his forces on a daunting flank march through nearly impassable mountain passes and took the enemy forces positioned at the mouth of the Khyber Pass completely by surprise, utterly beating them despite being outnumbered two-to-one. This led to the capture of Ghazni, Kabul, Peshawar, Sindh, and Lahore. As he moved into the Mughal territories, he was loyally accompanied by his Georgian subject and future king of eastern Georgia, Erekle II, who led a Georgian contingent as a military commander as part of Nader's force.[50] Following the prior defeat of Mughal forces, he then advanced deeper into India, crossing the river Indus before the end of year. The news of the Iranian army's swift and decisive successes against the northern vassal states of the Mughal empire caused much consternation in Delhi, prompting the Mughal ruler, Muhammad Shah, to raise an army of some 300,000 men and march to confront Nader Shah.[51]

Despite being outnumbered by six to one, Nader Shah crushed the Mughal army in less than three hours at the huge Battle of Karnal on 13 February 1739. After this spectacular victory, Nader captured Mohammad Shah and entered Delhi.[52] When a rumour broke out that Nader had been assassinated, some Indians attacked and killed Iranian troops; by midday 900 Iranian soldiers had been killed.[53] Nader, furious, reacted by ordering his soldiers to sack the city. During the course of one day (22 March) 20,000 to 30,000 Indians were killed by the Iranian troops and as many as 10,000 women and children were taken as slaves, forcing Mohammad Shah to beg Nader for mercy.[54][53]

In response, Nader Shah agreed to withdraw, but Mohammad Shah paid the consequence in handing over the keys of his royal treasury, and losing even the fabled Peacock Throne to the Iranian emperor.[55] The Peacock Throne, thereafter, served as a symbol of Iranian imperial might. It is estimated that Nader took away with him treasures worth as much as seven hundred million rupees. Among a trove of other fabulous jewels, Nader also looted the Koh-i-Noor (meaning "Mountain of Light" in Persian) and Darya-ye Noor (meaning "Sea of Light") diamonds. The Iranian troops left Delhi at the beginning of May 1739, but before they left, he ceded back to Muhammad Shah all territories to the east of the Indus which he had overrun.[56] The booty they had collected was loaded on 700 elephants, 4,000 camels, and 12,000 horses.[53]

Nader Shah left the area via the mountains in Northern Punjab. Learning of his planned route, the Sikhs started gathering light cavalry bands, and planned an attack to capture his plunder.[57] The Sikhs fell upon Nader's army in the Chenab valley, and seized a large amount of the booty and freed most of the slaves in captivity.[58][59][60][61] The Persians, however, were unable to pursue the Sikhs, because they were overloaded with the remaining plunder and overwhelmed by the terrible heat of that May.[62] Traveling with an advance guard, Nader Shah stopped at Lahore where he learned of his losses.[62][63] He traveled back to his forces, accompanied by Governor Zakariya Khan. Upon learning about the Sikhs, he told Khan that these rebels would one day rule the land.[citation needed] Still, the remaining plunder his forces had seized from India was so much that Nader was able to stop taxation in Iran for three years following his return.[64][65][66]

Many historians believe that Nader attacked the Mughal Empire to give his country some breathing space after previous turmoil. His successful campaign and replenishment of funds meant that he could continue his wars against Iran's archrival and neighbour, the Ottoman Empire,[24][page needed] as well as the campaigns in the North Caucasus. Nader also secured one of the Mughal emperor's daughters, Jahan Afruz Banu Begum, as a bride for his youngest son.

Central Asia, North Caucasus, Arabia, and the second Ottoman war

[edit]

The Indian campaign was the zenith of Nader's career. Afterwards he became increasingly despotic as his health declined markedly. Nader had left his son Reza Qoli Mirza to rule Iran in his absence. Reza had behaved highhandedly and somewhat cruelly but he had kept the peace in Iran. Having heard rumours that his father had died, he had made preparations for assuming the crown. These included the murder of the former shah Tahmasp and his family, including the nine-year-old Abbas III. On hearing the news, Reza's wife, who was Tahmasp's sister, committed suicide. Nader was not impressed with his son's waywardness and reprimanded him, but he took him on his expedition to conquer territory in Transoxiana. In 1740, he conquered the Khanate of Khiva. After the Iranians had forced the Uzbek Khanate of Bukhara to submit, Nader wanted Reza to marry the khan's elder daughter because she was a descendant of his hero Genghis Khan, but Reza flatly refused and Nader married the girl himself.[67]

With regard to Central Asia, Nader viewed Merv (present-day Bayramali, Turkmenistan) vital to his north-eastern defenses. He also tried to secure the ruler of Bukhara as his vassal, imitating previous great conquerors of Mongol-Timurid descent. According to a British scholar Peter Avery, Nader's attitude towards Bukhara was irredentist to an extent that he "may even have thought that, if only the Ottoman power in the west could be contained, he might make Bukhara a base for conquests further afield in Central Asia". Nader dispatched numerous artisans to Merv in a move to prepare for an improbable conquest of distant Kashgaria. Such a campaign did not materialize, but Nader frequently sent funds and engineers to Merv trying to restore its prosperity and rebuild its ill-fated dam. Merv, however, did not become prosperous.[68]

Nader now decided to punish Dagestan for the death of his brother Ebrahim Qoli on a campaign a few years earlier. In 1741, while Nader was passing through the forest of Mazanderan on his way to fight the Dagestanis, an assassin took a shot at him but Nader was only lightly wounded. He began to suspect his son was behind the attempt and confined him to Tehran. Nader's increasing ill health made his temper ever worse. Perhaps it was his illness that made Nader lose the initiative in his war against the Lezgin tribes of Dagestan. Frustratingly for him, they resorted to guerrilla warfare and the Iranians could make little headway against them.[69] Though Nader managed to take most of Dagestan during his campaign, the effective guerrilla warfare as deployed by the Lezgins, but also the Avars and Laks made the Iranian re-conquest of the particular North Caucasian region a short lived one; several years later, Nader was forced to withdraw. During the same period, Nader accused his son of being behind the assassination attempt in Mazanderan. Reza Qoli angrily protested his innocence, but Nader had him blinded as punishment, and ordered his eyes to be brought to him on a platter. When his orders had been carried out, however, Nader instantly regretted it, crying out to his courtiers, "What is a father? What is a son?"[70]

Soon afterwards, Nader started executing the nobles who had witnessed his son's blinding. In his last years, Nader became increasingly paranoid, ordering the assassination of large numbers of suspected enemies. Following the orders of Nader Shah, his soldiers executed 150 monks at Monastery of Saint Elijah after they refused to convert to Islam.[71] With the wealth he gained, Nader started to build an Iranian navy. With lumber from Mazandaran, he built ships in Bushehr. He also purchased thirty ships in India.[1] He recaptured the island of Bahrain from the Arabs. In 1743, he conquered Oman and its main capital Muscat. In 1743, Nader started another war against the Ottoman Empire. Despite having a huge army at his disposal, in this campaign Nader showed little of his former military brilliance. It ended in 1746 with the signing of a peace treaty, the Treaty of Kerden, in which the Ottomans agreed to let Nader occupy Najaf.[72]

Domestic policies

[edit]

Nader changed the Iranian coinage system. He minted silver coins, called Naderi, that were equal to the Mughal rupee.[1] Nader discontinued the policy of paying soldiers based on land tenure.[1] Like the late Safavids he resettled tribes. Nader Shah transformed the Shahsevan, a nomadic group living around Azerbaijan whose name literally means "shah lover", into a tribal confederacy which defended Iran against the neighbouring Ottomans and Russians.[73][74] In addition, he increased the number of soldiers under his command and reduced the number of soldiers under tribal and provincial control.[1] His reforms may have strengthened the country, but they did little to improve Iran's suffering economy.[1] He also always paid his troops on time, no matter what.[75]

Foreign policies

[edit]

In order to construct a broad political framework that could link him to the Ottomans and Mughals more closely than the Safavids had been, Nader Shah started creating new concepts. One of these was a focus on a shared Turkmen descent, by having several official documents evoke how Nader Shah, the Ottomans, Uzbeks, and Mughals all had a shared Turkmen background. In a broad sense, this concept mirrored the origin fables of 15th century Anatolian Turkmen dynasties.[1] The Ottomans, however, were left unimpressed with Nader Shah's new concept. According to the modern historian Ernest Tucker, comparing this concept to an early version of "pan-Turkism" would be "anachronistic and misleading." He adds that this was part of unpolished drafts of concepts that would get polished throughout the 11 years of Nader Shah's reign, and would include wide political and religious aspects.[76]

Nader's concepts regarding the Ja'farism and common Turkmen descent were directed primarily at the Ottomans and Mughals. He may have perceived a need to unite disparate components of the ummah against the expanding power of Europe at that time, however his view of Muslim unity was different from later concepts of it.[1]

He proposed a peace treaty with the Ottomans, in it, he proclaimed the Persians wanted the Ja'fari Maddhab to be incorporated as a Madhhab of Islam. An Ottoman delegation led by Mirahor Mustafa Paşa visited Nader in 1346-1340 to have negotiations in regards to this.[d] While only a nominal claim, Nader's army was increasingly drawing from Sunni Afghans, Kurds, Turkmens, Baloch, and others who were happy with a less sectarian Persia. Externally he presented Persia as completely sympathetic to Sunnis. He probably did this for political reasons in order to increase his legitimacy within the Muslim world; he would have never been accepted if he remained a radical Shia Muslim like the Safavid Shahs. Though as stated countless times before, internally, he was probably agnostic.[24][page needed]

Whenever Nader laid siege to a city, he would construct a city of his own outside the walls. His encampment was filled with markets, mosques, bathhouses, coffeehouses, and stables. He did this to show the besieged his army would be there for the long haul, to prevent diseases from spreading within his troops' ranks, and to occupy his troops' time.[24][page needed]

Death and legacy

[edit]

Nader became increasingly cruel as a result of his illness and his desire to extort more and more tax money to pay for his military campaigns. New revolts broke out and Nader crushed them ruthlessly, building towers from his victims' skulls in imitation of his hero Timur. In 1747, Nader set off for Khorasan, where he intended to punish Kurdish rebels. Some of his officers and courtiers feared he was about to execute them and plotted against him, including two of his relatives: Muhammad Quli Khan, the captain of the guards, and Salah Khan, the overseer of Nader's household. Nader Shah was assassinated on 20 June 1747,[78] at Quchan in Khorasan. He was surprised in his sleep by around fifteen conspirators, and stabbed to death. Nader was able to kill two of the assassins before he died.[79]

The most detailed account of Nader's assassination comes from Père Louis Bazin, Nader's physician at the time of his death, who relied on the eyewitness testimony of Chuki, one of Nader's favourite concubines:

Around fifteen of the conspirators were impatient or merely eager to distinguish themselves, and so turned up prematurely at the agreed meeting place. They entered the enclosure of the royal tent, pushing and smashing their way through any obstacles, and penetrated into the sleeping quarters of that ill-starred monarch. The noise they made on entering woke him up: 'Who goes there?' he shouted out in a roar. 'Where is my sword? Bring me my weapons!' The assassins were struck with fear by these words and wanted to escape, but ran straight into the two chiefs of the murder-conspiracy, who allayed their fears and made them go into the tent again. Nader Shah had not yet had time to get dressed; Muhammad Quli Khan ran in first and struck him with a great blow of his sword which felled him to the ground; two or three others followed suit; the wretched monarch, covered in his own blood, attempted – but was too weak – to get up, and cried out, 'Why do you want to kill me? Spare my life and all I have shall be yours!' He was still pleading when Salah Khan ran up, sword in hand and severed his head, which he dropped into the hands of a waiting soldier. Thus perished the wealthiest monarch on earth.[53]

After his death, he was succeeded by his nephew Ali Qoli, who renamed himself Adel Shah ("righteous king"). Adel Shah was probably involved in the assassination plot.[34] Adel Shah was deposed within a year. During the struggle between Adel Shah, his brother Ibrahim Khan and Nader's grandson Shah Rukh, almost all provincial governors declared independence, established their own states, and the entire Empire of Nader Shah fell into anarchy. Oman and the Uzbek khanates of Bukhara and Khiva regained independence, while the Ottoman Empire regained the lost territories in Western Armenia and Mesopotamia. Finally, Karim Khan founded the Zand dynasty and became ruler of Iran by 1760. Erekle II and Teimuraz II, who, in 1744, had been made the kings of Kakheti and Kartli respectively by Nader himself for their loyal service,[80] capitalized on the eruption of instability, and declared de facto independence. Erekle II assumed control over Kartli after Teimuraz II's death, thus unifying the two as the Kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti, becoming the first Georgian ruler in three centuries to preside over a politically unified eastern Georgia,[81] and due to the frantic turn of events in mainland Iran he would be able to maintain its autonomy until the advent of the Iranian Qajar dynasty.[82] The rest of the Iranian territories in the Caucasus, comprising modern-day Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Dagestan broke away into various khanates. Until the advent of the Zands and Qajars, its rulers had various forms of autonomy, but stayed vassals and subjects to the Iranian king.[83] In the far east, Ahmad Shah Durrani had already proclaimed independence, marking the foundation of modern Afghanistan. Iran finally lost Bahrain to House of Khalifa during Invasion of Bani Utbah in 1783.

Nader Shah was well known to the European public of the time. In 1768, Christian VII of Denmark commissioned Sir William Jones to translate a Persian language biography of Nader Shah written by his Minister Mirza Mehdi Khan Astarabadi into French.[84] It was published in 1770 as Histoire de Nadir Chah.[85] Nader's Indian campaign alerted the East India Company to the extreme weakness of the Mughal Empire and the possibility of expanding to fill the power vacuum. Without Nader, "eventual British [rule in India] would have come later and in a different form, perhaps never at all – with important global effects".[86] Joseph Stalin, leader of the Soviet Union is said to have admired him and called him a teacher (alongside Ivan the Terrible).[87]

The military success of Nader was nearly unprecedented for Muslim Shahs.[24][page needed]

Flag

[edit]Nader Shah consciously avoided using the colour green, as green was associated with Shia Islam and the Safavid dynasty.[88]

Personality

[edit]The strong character of Nader Shah is indicated by the fact that having achieved much fame and glory, he did not allow his pleasers to find great ancestors in the darkness of his origin. He never boasted of a proud genealogy; on the contrary, he often spoke of his simple origin. Even his chronicler was forced to limit himself by saying that diamond was valued not by the rock where it had been found, but by its splendor. There is a story that says, having demanded the daughter of his defeated enemy Muhammad Shah, the Emperor of Delhi, to marry his son Nasrullah, he received the answer that a royal lineage up to the 7th generation was required for marriage with a princess from the House of Timur.[89]

"Tell him," Nader replied, "that Nasrullah is the son of Nader Shah, the son and grandson of the sword, and so on, not until the 7th, but until the 70th generation."[89] Nader had the greatest contempt for the weak, depraved Muhammad Shah, who, according to the local chronicler of that era, "was always with his mistress in his arms and a glass in his hand," and was the lowest libertine and simply a puppet ruler.[90] Nader Shah once had a conversation with a holy man about paradise. After what that man described miracles and pleasures of the heaven, the shah asked:

"Are there such things as war and victory over the enemy in paradise?" When the man answered negatively, Nader replied: "How can there be any pleasure then?"[citation needed]

French orientalist Louis Bazin describes the personality of Nader Shah as follows:

Despite his obscure background, he looked born for the throne. Nature endowed him with all the great qualities that make heroes ... His dyed beard made a sharp contrast with his completely gray hair; his natural physique was strong, tall, and his waist was proportional to his growth; his expression was gloomy, with an oblong face, an aquiline nose and a beautiful mouth, but with his lower lip protruding forward. He had small penetrating eyes with a sharp and piercing gaze; his voice was rude and loud, although he knew how to soften it on occasion, as required by personal interest...

He did not have a permanent home – his military camp was his court; his palace was his tent, and his closest confidants were his bravest soldiers ... Undaunted in battle, he brought courage, and was always in the thick of danger among his brave men, as long as the battle lasted ... He did not neglect any of the measures dictated by foresight ... Nevertheless, the repulsive greed and unprecedented cruelties that wore his subjects, ultimately led to his fall, and the extremes and horrors that were caused by him, made Persia cry. He was adored, feared and cursed at the same time.[91]

English traveler Jonas Hanway, who lived in the courtyard of Nader Shah, describes him:

Nader Shah is taller than 6 feet, well-built, very physically strong. He has such an unusually loud voice that he can give orders to his people at a distance of about 100 yards. He drinks wine moderately, hours of his rest among ladies are very rare, his food is simple, and if government affairs require his presence, he rejects his meal and satisfies hunger with fried peas (which he always carries in his pocket) and a sip of water... He is extremely generous, especially to his warriors, and generously rewards all who have distinguished themselves in his service. At the same time, he is very severe and strict in relation to discipline, punishing with the death penalty all who have committed major misconduct... He never forgives the guilty, no matter what rank he is. Being on a march or in the field, he confines himself to food, drink and sleep of a simple soldier and forces all his officers to follow the same harsh discipline. He has such a strong physique that he often sleeps on a frosty night on bare ground in the open air, wrapping himself only in his cloak and putting a saddle under his head as a pillow. In private conversations, no one is allowed to talk about government affairs.[92]

Member of the French Academy of Sciences, Pierre Bayen wrote about Nader Shah the following:

He was the horror of the Ottoman Empire, the conqueror of India, the ruler of Persia and all of Asia. His neighbors respected him, his enemies were afraid of him, and he lacked only the love of his subjects.[93][page needed]

One Punjabi contemporary poet described the rule of Nader as a time "when all of India trembled with horror."[94] The Kashmiri historian Lateef described him as follows: "Nader Shah, the horror of Asia, the pride and savior of his country, the restorer of her freedom and conqueror of India, who, having a simple origin, rose to such greatness that monarchs rarely have from birth."[95] Joseph Stalin used to read about Nader Shah and admired him, calling him, along with Ivan the Terrible, a teacher. In Europe, Nader Shah was compared to Alexander the Great. Starting from a young age, Napoleon Bonaparte also used to read about and admire Nader Shah. Napoleon considered himself the new Nader, and he himself was later called European Nader Shah.[96]

Nader was somewhat austere in his daily life. He always preferred plain garments and disdained courtly sophistication and lavish lifestyles, particularly that of the Safavids. He ate simple foods and restrained himself from being tied to his harem and liquor, unlike Soltan Hoseyn and Tahmasp II.[97]

Nader did not want historians to detail his military victories too closely because he feared others would copy his brilliant techniques on the battlefield.[24][page needed]

See also

[edit]- Nader Shah's Central Asian campaign

- History of the Caucasus

- Afsharid navy

- Safavid conversion of Iran to Shia Islam

- Treaty of Resht

- Jahangusha-i Naderi, the most important book on the reign and wars of Nader Shah

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Nader's exact date of birth is unknown but 6 August 1698 is the "likeliest" according to Axworthy, p. 17 (and note) and The Cambridge History of Iran (vol. 7, p. 3); other biographers favour 1688.

- ^ Or Nadir Shah. Also known as Nāder Qoli Beyg (نادرقلیبیگ) or Tahmāsb Qoli Khan (تهماسبقلی خان)

- ^ The six other tribes were the Shamlu, Rumlu, Ustajlu, Takallu, Dhu'l-Qadar and Qajar.[13]

- ^ This visit was documented by Tanburi Arutin, musician of the delegation.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Tucker 2006a.

- ^ Colebrooke 1877, p. 374.

- ^ Axworthy 2006, pp. 159, 279.

- ^ a b Axworthy 2006, p. 17.

- ^ a b Axworthy 2006, p. 34.

- ^ Iranian Studies, Volume 27, Issue 1-4: Religion and Society in Islamic Iran during the Pre-Modern Era, 1994, pp. 163–179.

- ^ Tucker 2006b.

- ^ Axworthy 2006, pp. 168–170.

- ^ "Nader Shah, a military genius". Tehran Times. 1 July 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2025.

- ^ Cambridge History of Iran Vol. 7, p. 59.

- ^ Elena Andreeva; Louis A. DiMarco; Adam B. Lowther; Paul G. Pierpaoli Jr.; Spencer C. Tucker; Sherifa Zuhur (2017). "Iran". In Tucker, Spencer C. (ed.). Modern Conflict in the Greater Middle East: A Country-by-Country Guide. ABC-CLIO. pp. 83–108. ISBN 9781440843617.

Under its great ruler and military leader Nader Shah (1736–1747), Persia was arguably the world's most powerful empire

- ^ Axworthy 2006, pp. 282–283.

- ^ a b Lockhart 1938, p. 17.

- ^ a b Stöber 2010.

- ^ Avery 1991, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Lockhart 1938, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Axworthy 2006, p. 18.

- ^ a b c Axworthy 2006, p. 19.

- ^ Lockhart 1938, p. 274.

- ^ Avery 1991, p. 3.

- ^ Axworthy 2006, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Axworthy 2006, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Axworthy 2006, p. 52.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Axworthy 2006.

- ^ PHI, p. 30.

- ^ This section: Axworthy, pp. 17–56.

- ^ Houtsma & van Donzel 1993, p. 760.

- ^ Axworthy 2006, pp. 57–74.

- ^ Axworthy 2006, pp. 75–116.

- ^ Allen & Muratov 2011, p. 7.

- ^ Freygang, p. 14.

- ^ Allen & Muratov 2011, p. 11.

- ^ Freygang, p. 76.

- ^ a b Elton L. Daniel, "The History of Iran" (Greenwood Press 2000) p. 94

- ^ Lawrence Lockhart Nadir Shah (London, 1938)

- ^ a b c d e Fisher et al. 1991, p. 34.

- ^ Fisher et al. 1991, p. 36.

- ^ Fisher et al. 1991, p. 35.

- ^ This section: Axworthy, pp. 137–174.

- ^ Fisher et al. 1991, pp. 34–36.

- ^ Axworthy 2009, pp. 161–162.

- ^ Axworthy 2009, pp. 172–173.

- ^ The Afghan Interlude and the Zand and Afshar Dynasties, Kamran Scot Aghaie, The Oxford Handbook of Iranian History, ed. Touraj Daryaee, (Oxford University Press, 2012), 316.

- ^ Axworthy 2007, p. 635–646.

- ^ Steven R. Ward. (2014). Immortal, Updated Edition: A Military History of Iran and Its Armed Forces. Georgetown University Press. p. 52. ISBN 9781626160323.

- ^ Axworthy, p. 168.

- ^ Kırca, Ersin (30 December 2020). "OSMANLI – İRAN RESMÎ YAZIŞMALARINA GÖRE OSMANLI DEVLETİ'NİN NADİR ŞAH VE CAFERİLİK MEZHEBİNE YAKLAŞIMI (1736-1746)". Sosyal Bilimler Araştırmaları Dergisi (in Turkish). 15 (2): 392–408. doi:10.48145/gopsbad.815609. ISSN 2564-680X.

- ^ Axworthy 2009, p. 76.

- ^ Raghunath Rai. History. p. 19 FK Publications ISBN 8187139692

- ^ David Marshall Lang (2009) [1957]. Russia and the Armenians of Transcaucasia, 1797–1889: a documentary record. Columbia University Press. p. 142. ISBN 9780231937108.

- ^ Axworthy 2009, p. 196.

- ^ PHI, p. 33.

- ^ a b c d Dalrymple & Anand 2017, pp. 52–60.

- ^ Axworthy 2006, p. 8.

- ^ Singh 1963, p. 237.

- ^ Axworthy 2006, pp. 212, 216.

- ^ Singha, Bhagata (1993). A History of the Sikh Misals. Patiala, India: Publication Bureau, Punjabi University.

- ^ Gupta 1999, p. 54.

- ^ Mahajan 2020, p. 57.

- ^ Joseph 2016.

- ^ Gandhi 1999, pp. 117–118.

- ^ a b Gupta 1999, p. 5.

- ^ Singh 1963, p. 125.

- ^ "Nadir Shah". Encyclopædia Britannica. 12 September 2023.

- ^ Axworthy pp. 1–16, 175–210

- ^ Singh 1963, p. 124–125.

- ^ Soucek 2000, p. 195.

- ^ Avery 1991, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Spencer C. Tucker. (2009). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. p. 739. ISBN 9781851096725.

- ^ Axworthy 2006, p. 240.

- ^ Mendoza, Martha; Alleruzzo, Maya; Janssen, Bram (20 January 2016). "IS Destroys Religious Sites: The oldest Christian monastery in Iraq has been reduced to a field of rubble by IS's relentless destruction of ancient cultural sites". U.S. News & World Report. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 21 January 2016.

- ^ This section: Axworthy, pp. 175–274.

- ^ Floor, Willem (July–September 1999). "Richard Tapper's Frontier Nomads of Iran: A Political and Social History of the Shahsevan". Journal of the American Oriental Society (Book review). 119 (3): 542–544 [543]. doi:10.2307/605982. JSTOR 605982.

- ^ Daniel, Elton L. The History of Iran. Greenwood Publishing Group: 2000. p. 90.

- ^ Axworthy 2009, pp. 158.

- ^ Tucker 2021, p. 14.

- ^ Axworthy 2006, p. 274.

- ^ Perry 1984, pp. 587–589.

- ^ Iran Chamber Soc n.d.

- ^ Ronald Grigor Suny (1994). The Making of the Georgian Nation. Indiana University Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0253209153.

- ^ Hitchins 1998, pp. 541–542.

- ^ Fisher et al. 1991, p. 328.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Soviet law, by Ferdinand Joseph Maria Feldbrugge, Gerard Pieter van den Berg, William B. Simons, p. 457

- ^ Perry 1987.

- ^ Axworthy 2006, p. 330.

- ^ Axworthy 2006, p. xvi.

- ^ Axworthy, Michael (2010). Sword of Persia: Nader Shah, from Tribal Warrior to Conquering Tyrant. Bloomsbury. ISBN 9780857733474.

- ^ Shapur Shahbazi, 1999 at Encyclopædia Iranica.

- ^ a b Axworthy 2009, p. 11.

- ^ Gordon 1896.

- ^ Dalrymple & Anand 2017, p. 48.

- ^ Kaul, R.B. "Ballad on Nadir Shah's Invasion in India", pp. 3–4

- ^ Dalrymple & Anand 2017, p. ?.

- ^ Tucker 2006b, p. 6.

- ^ Kaul, R.B. "Ballad on Nadir Shah's Invasion in India", p. 16

- ^ Matthee 2018, p. 471.

- ^ Axworthy 2009, p. 125.

Sources

[edit]- T.E. Colebrooke (April 1877). "On imperial and other titles". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 9 (2): 314–420. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00167784. JSTOR 25581272. S2CID 162599106.

- Allen, William Edward David; Muratov, Paul (2011). Caucasian Battlefields: A History of the Wars on the Turco-Caucasian Border 1828–1921. Cambridge University Press. pp. 4–19. ISBN 978-1108013352.

- Axworthy, Michael (2009). The Sword of Persia: Nader Shah, from Tribal Warrior to Conquering Tyrant. I.B. Tauris.

- Avery, Peter (1991). "Nādir Shāh and the Afsharīd legacy". In Avery, Peter; Hambly, Gavin R. G.; Melville, Charles Peter (eds.). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 7: From Nadir Shah to the Islamic Republic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 3–62. ISBN 0-521-20095-4.

- Axworthy, Michael (2006). The Sword of Persia: Nader Shah, from Tribal Warrior to Conquering Tyrant. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1850437062.

- Axworthy, Michael (December 2007). "The Army of Nader Shah" (PDF). Iranian Studies. 40 (5): 635–646. doi:10.1080/00210860701667720. S2CID 159949082. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016.

- Barati, András (2019). "The Succession Struggle Following the Death of Nādir Shāh (1747–1750)". Orpheus Noster 11/4: 44–58. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- Browne, Edward G. "An Outline of the History of Persia During the Last Two Centuries (A.D. 1722–1922)". London: Packard Humanities Institute. p. 30. Archived from the original on 26 October 2014. Retrieved 24 September 2010.

- Dalrymple, William; Anand, Anita (2017). Koh-i-Noor: The History of the World's Most Infamous Diamond. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 52–60. ISBN 978-1408888827.

- Fisher, William Bayne; Avery, P.; Hambly, G. R. G; Melville, C. (1991). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 7. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521200954. Archived from the original on 13 January 2023. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- Freygang, Frederika von; Freygang, Wilhelm von (1823). Letters from the Caucasus and Georgia: To which are Added, the Account of a Journey Into Persia in 1812, and an Abridged History of Persia Since the Time of Nadir Shah. Harvard University: J. Murray.

- Gandhi, Rajmohan (1999). Revenge and Reconciliation: Understanding South Asian History. Penguin Books. pp. 117–118. ISBN 978-0140290455.

- Gordon, T. E. (1896). Persia Revisited.

- Gupta, Hari Ram (1999). History of the Sikhs: Evolution of Sikh confederacies, 1708–69. Munshiram Manoharlal. p. 54. ISBN 978-8121502481.

- "History of Iran: Afsharid Dynasty (Nader Shah)". Iran Chamber Society. n.d. Archived from the original on 24 November 2010. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- Hitchins, Keith (1998). "Erekle II". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. VIII/5: English IV–Eršād al-zerāʿa. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 541–542. ISBN 978-1-56859-054-7.

- Houtsma, M. Th; van Donzel, E. (1993). E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936. Brill. p. 760. ISBN 90-04-08265-4.

- Joseph, Paul (2016). The Sage Encyclopedia of War: Social Science Perspectives. Sage Publications. ISBN 978-1483359908. Archived from the original on 27 April 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- Lockhart, Laurence (1938). Nadir Shah: A Critical Study Based Mainly upon Contemporary Sources. Luzac & Co. ISBN 978-0404562908.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Mahajan, Vidya Dhar (2020). Modern Indian History. S. Chand Limited. p. 57. ISBN 978-9352836192. Archived from the original on 27 April 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- Matthee, Rudi (2018). "Nādir Shāh in Iranian Historiography: Warlord or National Hero?". In Schmidtke, Sabine (ed.). Studying the Near and Middle East at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, 1935–2018. Gorgias Press. pp. 467–474.

- Perry, John R. (1979). Karim Khan Zand: A History of Iran, 1747–1779. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226660981.

- Perry, John R. (1984). "Afsharids". Encyclopædia Iranica, Vol. I, online ed., Fasc. 6. New York. pp. 587–589.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Perry, John R. (1997). "Ebrāhīm Shah Afšār". Encyclopædia Iranica, Vol. VIII, online edition, Fasc. 1. New York. pp. 75–76.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Perry, J.R. (1987). "Astarābādī, Mahdī Khan". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 8. pp. 844–845.

- Singh, Khushwant (1963). A History of the Sikhs. Vol. 1, 1469–1839. Princeton University Press – via Internet Archive.

- Soucek, Svat (2000). A History of Inner Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521657044.

- Stöber, Georg (2010). "Afshār". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill Online. ISSN 1873-9830.

- Tucker, Ernest (2006a). "Nāder Shāh". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Tucker, Ernest S. (2006b). Nadir Shah's Quest for Legitimacy in Post-Safavid Iran. University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0813029641.

- Perry, John. R. (1991). "The Zand dynasty". In Avery, Peter; Hambly, Gavin R. G.; Melville, Charles Peter (eds.). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 7: From Nadir Shah to the Islamic Republic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 63–104. ISBN 0-521-20095-4.

- Tucker, Ernest (2012). "Afshārids". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill Online. ISSN 1873-9830.

- Tucker, Ernest (2021). Melville, Charles Melville (ed.). The Contest for Rule in Eighteenth-Century Iran: Idea of Iran Vol. 11. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-0755645992.

- Minorsky, Vladimir (1939). "Review of Nadir Shah". Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London. 9 (4): 1119–1123. ISSN 1356-1898. JSTOR 608033.

Further reading

[edit]- Matthee, Rudi (2023). "The wrath of God or national hero? Nader Shah in European and Iranian historiography". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 34: 109–127. doi:10.1017/S1356186322000694.

- Michael Axworthy, Iran: Empire of the Mind: A History from Zoroaster to the Present Day (Paperback) ISBN 0-14-103629-X Publisher Penguin (2008)

- Rota, Giorgio (2020). "In a League of Its Own? Nāder Šāh and His Empire". In Rollinger, Robert; Degen, Julian; Gehler, Michael (eds.). Short-term Empires in World History. Springer. pp. 215–226.

External links

[edit]- Coins of Nader Shah at the Numista Catalogue

.jpg/250px-Contemporary_portrait_of_Nader_Shah._Artist_unknown,_created_in_ca._1740_in_Iran_(cropped).jpg)

.jpg)