Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Pointed arch

View on Wikipedia

A pointed arch, ogival arch, or Gothic arch is an arch with a pointed crown, whose two curving sides meet at a relatively sharp angle at the top of the arch.[1] Also known as a two-centred arch, its form is derived from the intersection of two circles.[2] This architectural element was particularly important in Gothic architecture. The earliest use of a pointed arch dates back to bronze-age Nippur. As a structural feature, it was first used in eastern Christian architecture, Byzantine architecture and Sasanian architecture, but in the 12th century it came into use in France and England as an important structural element, in combination with other elements, such as the rib vault and later the flying buttress. These allowed the construction of cathedrals, palaces and other buildings with dramatically greater height and larger windows which filled them with light.[3]

Early arches

[edit]

Crude arches pointed in shape have been discovered from the Bronze Age site of Nippur dated earlier than 2700 BC. The palace of Nineveh also has pointed arched drains but they have no true keystone.[4] There are many other Greek examples, late Roman and Sassanian examples, mostly evidenced in early church building in Syria and Mesopotamia, but also in engineering works such as the Byzantine Karamagara Bridge, with a pointed arch of 17 m (56 ft) span, making "the pre-Muslim origins of pointed architecture an unassailable contention".[5]

The clearest surviving example of pre-islamic pointed arches are the two pointed arches of Chytroi-Constantia Aqueduct in Cyprus dating back to the 7th century CE.[6]

Pointed arches – Islamic architecture

[edit]The pointed arch became an early feature of architecture in the Islamic world. It appeared in early Islamic architecture, including in both Umayyad architecture and Abbasid architecture (late 7th to 9th centuries).[7][8] The most advanced form of pointed arch in Islamic architecture was the four-centred arch, which appeared in the architecture of the Abbasids. Early examples include the portals of the Qubbat al-Sulaiybiyya, an octagonal pavilion, and the Qasr al-'Ashiq palace, both at Samarra, built by the Abbasid caliphs in the 9th century for their new capital.[8] It later appeared in Fatimid architecture in Egypt[9] and became characteristic of the architecture of Persianate cultures, including Persian architecture,[10] the architecture of the Timurid Empire,[11] and Indo-Islamic architecture.[12][13][14]

-

Restored Abbasid architecture arches of the city gates of Samarra (9th century)

-

Central prayer niche in the Mosque of Ibn Tulun in Cairo (876–879 CE)

-

Bibi-Khanym Mosque, Samarkand, Uzbekistan (1399–1404)

-

The Eurymedon Bridge in Turkey, originally built by the Romans and rebuilt with a pointed arch in the 13th century by the Seljuk Turkish Sultan

-

Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque, Isfahan Iran (1603–1619)

The evolution of the pointed arch in Islamic architecture was associated with increases between the centers of the circles forming the two sides of the arch (making the arch less "blunt" and more "sharp"), from 1⁄10 of the span in Qusayr 'Amra (712-715 AD), to 1⁄6 in Hammam as-Sarah (725-730), to 1⁄5 in Qasr Al-Mshatta (744), and finally to 1⁄3 in Fustat (861-862).[15]

The appearance of the pointed arch in European Romanesque architecture during the second half of the 11th century, for example at Cluny Abbey, is ascribed to the Islamic influence.[16] Some researchers follow Viollet-le-Duc in acknowledging the spread of Arabic architecture forms through Italy, Spain and France, yet suggesting an independent invention of the pointed shape in some cases. The change was supposedly driven by the observations of the collapses of semicircular arches, with the crown moving down and haunches out. In this interpretation, the pointed arch was an attempt to strengthen the semicircular arch against a collapse by moving the crown up and haunches in.[15]

Gothic architecture – pointed arches and rib vaulting

[edit]The reduction of thrust on supports that a pointed arch provided, as compared to a semicircular one with the same load and span, was quickly recognized by medieval European builders. They achieved this at first through experimentation, but technical literature dating to the Renaissance indicates that formulas for determining thrust may have been in use during the medieval period.[15]

-

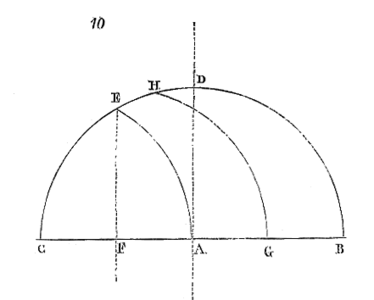

Thirteenth-century illustration by Villard de Honnecourt of how different pointed arches can be made from a single curve of the compass. From Eugène Viollet-le-Duc ""Dictionnaire raisonné de l’architecture française du XIe au XVIe siècle"'

-

Gothic pointed windows, colonnades and vaults at the Abbey of Saint-Denis, Paris, drawn by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc

-

The dynamics of a rib vault, with outward and downward pressure from ribs balanced by columns and buttresses. The pieces can stand by themselves, without cement. (National Museum of French Monuments, Paris)

-

An early sexpartite rib vault drawn by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc

-

Rib vaults of Durham Cathedral (1135–1490)

-

Choir of Lessay Abbey in Normandy (1064–1178)

-

Vaulted ceiling of Cefalù Cathedral in Sicily (1131–1240)

-

Chapel of Saint Firmin in Basilica of Saint-Denis (1140–1144)

-

Choir of Beauvais Cathedral (begun 1225) (48.5 meters (159 ft) high

Rib vaults

[edit]In the 12th century, architects in Sicily, England and France discovered a new use for the pointed arch. They began using the pointed arch to create the rib vault, which they used to cover the naves of abbeys and cathedrals. One of the first Gothic rib vaults was built at Durham Cathedral in England (1135–1490).[3] Others appeared in the deambulatory of the Abbey of Saint Denis in Paris (1140–1144), Lessay Abbey in Normandy (1064–1178), Cefalù Cathedral in Sicily, (1131–1240). and the Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris.

The rib vault quickly replaced the Romanesque barrel vault in the construction of cathedrals, palaces, and other large structures. In a barrel vault, the round arch over the nave pressed down directly onto the walls, which had to be very thick, with few windows, to support the weight. In the rib vault, the thin stone ribs of the pointed arches distributed the weight outwards and downwards to the rows of pillars below. The result was that the walls could be thinner and higher, and they could have large windows between the columns. With the addition of the flying buttress, the weight could be supported by curving columns outside the building, which meant that the Cathedrals could be even taller, with immense stained glass windows.[17]

In the earliest type of Gothic rib vault, the sexpartite vault, the vault had a transversal pointed arch, and was divided by the ribs into six compartments. It could only cross a limited amount of space, and required a system of alternating columns and pillars. This type was used in Sens Cathedral and Notre-Dame de Paris. A new version was soon introduced, which reduced the number of compartments from six to four, distributed the weight equally to four pillars, eliminating the need for alternating columns and pillars, and allowed the vault to span a wider space. This quadripartite vault was used at Amiens Cathedral, Chartres Cathedral, and Reims Cathedral, and gave these structures unprecedented height.[18]

Portals

[edit]Portals of Cathedrals in the Gothic period were usually in the form of a pointed arch, surrounded by sculpture, often symbolizing the entrance to heaven.

-

Portal of Toledo Cathedral, the "Door of the Lions" (1226–1493)

-

West portal of Reims Cathedral (1211–1345)

-

Central portal of Chartres Cathedral (1194–1220)

Windows

[edit]The window in the form of a pointed arch is a common characteristic of the Gothic style. Windows sometimes were constructed in the classical form of a pointed arch, which is denominated an "equilateral arch", while others had more imaginative forms that combined various geometric forms (see #Forms). One common form was the lancet window, a tall and slender window with a pointed arch, which took its name from the lance. Lancet windows were often grouped into sets, with two, three or four adjacent windows.

-

Ruin of Aulne Abbey in Belgium (1214–1247)

-

Lancet windows

-

A Double-Lancet Window (about 1330) (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

-

Pointed windows of the nave of Sainte-Chapelle de Vincennes occupy near all the walls. (1379–1480)

The late Gothic, also known as the Flamboyant Gothic, had windows with pointed arches that occupied nearly all the space of the walls. Notable examples are the windows of Sainte-Chapelle de Vincennes (1379–1480)

-

Multiple arches of the Flamboyant Gothic at Sainte-Chapelle de Vincennes.

-

The Great Gate of Trinity College, Cambridge, an example of a Tudor Arch or Four-centred arch

Forms

[edit]

The most common form of the Gothic pointed arch in windows and arches was based upon an equilateral triangle, in which the three sides have an equal length (the span of the arch is equal to the arc radii). This so called equilateral arch had the great advantage of simplicity. Stone cutters, or hewers, could precisely draw the arc on the stone with a cord and a marker. This allowed arch stones to be cut at the quarry in quantity with great precision, then delivered and assembled at the site, where the layers put them together, with the assurance that they would fit. The use of the equilateral triangle was given a theological explanation – the three sides represented the Holy Trinity.[19]

In the later years of the flamboyant Gothic the arches and windows often took on more elaborate forms, with tracery circles and multiple forms within forms. Some used a modification of the horseshoe arch, borrowed from Islamic architecture.

The Tudor Arch of the Late Gothic style was a variation of the Islamic four-centred arch. A four-centred arch is a low, wide type of arch with a pointed apex. Its structure is achieved by drafting two arcs that rise steeply from each springing point on a small radius, and then turning into two arches with a wide radius and much lower springing point. It is a pointed sub-type of the general flattened depressed arch. Two of the most notable types are known as the Persian arch, which is moderately "depressed",[8] and the Tudor arch, which is flatter than the Persian arch, was widely used in English architecture, particularly during the Tudor dynasty (1485–1603).[20]

Revival of pointed arch

[edit]Though the Gothic pointed arch was largely abandoned during the Renaissance, replaced by more classical forms, it reappeared in the 18th and 19th century, Gothic Revival architecture. It was used in Strawberry Hill House, the residence in Twickenham, London built by Horace Walpole (1717–1797) from 1749 onward. It was usually used in churches and chapels, and later in the British Houses of Parliament in London, (1840–1876) rebuilt after the earlier building was destroyed by a fire. In the 19th century, pointed arches appeared in varied structures, including the Gothic train station in Peterhof, Russia (1857).

-

Strawberry Hill House, residence of Horace Walpole (1749 onward)

-

Entrance to Victoria's Tower of the Houses of Parliament, London (1840–1876)

-

New Peterhof railway station, Peterhof, Russia (1857)

-

Interior of Almudena Cathedral in Madrid (1889–1992)

Notes and citations

[edit]- ^ Bechmann (2017), p. 322.

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, Two-centred.

- ^ a b Mignon (2015), p. 10.

- ^ "The Project Gutenberg eBook of Mesopotamian Archæology, by Percy S. P. Handcock". www.gutenberg.org. Retrieved 2020-07-30.

- ^ Warren 1991, pp. 61–63

- ^ Stewart, Charles Anthony (2014). "Architectural Innovation in Early Byzantine Cyprus". Architectural History. 57: 1–29. ISSN 0066-622X.

- ^ Herzefeld, Ernst (2016) [1910]. "The Genesis of Islamic Art and the Problem of Mshatta". In Bloom, Jonathan M. (ed.). Early Islamic Art and Architecture. Translated by Hillenbrand, Fritz; Bloom, Jonathan M. Routledge. pp. 35–36. ISBN 9781351942584.

- ^ a b c Petersen (2002), pp. 25, 250–251.

- ^ M. Bloom, Jonathan; S. Blair, Sheila, eds. (2009). "Architecture". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. p. 109. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ M. Bloom, Jonathan; S. Blair, Sheila, eds. (2009). "Architecture". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. p. 100. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ Petersen (2002), pp. 283.

- ^ Burton-Page, John (2008). Indian Islamic Architecture: Forms and Typologies, Sites and Monuments. Brill. p. 20. ISBN 978-90-04-16339-3.

- ^ Mehrdad, Shokoohy; Shokoohy, Natalie E. (2020). Bayana: The Sources of Mughal Architecture. Edinburgh University Press. p. 479. ISBN 978-1-4744-6075-0.

- ^ Bandyopadhyay, Soumyen; Chauhan, Sagar (2019). "Herbert Baker, New Delhi and the reception of the classical tradition". In Temple, Nicholas; Piotrowski, Andrzej; Heredia, Juan Manuel (eds.). The Routledge Handbook on the Reception of Classical Architecture. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-69385-1.

- ^ a b c arco entry (in Italian) by C. Ewert in the Enciclopedia Treccani, 1991

- ^ Woodman & Bloom 2003, Pointed.

- ^ Renault & Lazé (2005), p. 34-35.

- ^ Renault & Lazé (2005), p. 34–35.

- ^ Bechmann (2017), pp. 207–215.

- ^ Pugin, Augustus (1821). Specimens of Gothic Architecture: Selected from Various Ancient Edifices in England. Vol. 1–2. p. 3.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bechmann, Roland (2017). Les Racines des Cathédrales (in French). Payot. ISBN 978-2-228-90651-7.

- Bony, Jean (1983). French Gothic Architecture of the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-02831-9.

- Ducher, Robert (1988). Caractéristique des Styles (in French). Flammarion. ISBN 978-2-08-011539-3.

- Mignon, Olivier (2015). Architecture des Cathédrales Gothiques (in French). Éditions Ouest-France. ISBN 978-2-7373-6535-5.

- Petersen, Andrew (2002). Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780203203873.

- Renault, Christophe; Lazé, Christophe (2005). Mémento Gisserot de l'architecture. Mémento Gisserot : histoire de l'art (in French). ISBN 9782877477635. OCLC 470449422.

- Warren, John (1991), "Creswell's Use of the Theory of Dating by the Acuteness of the Pointed Arches in Early Muslim Architecture", Muqarnas, vol. 8, Brill, pp. 59–65, doi:10.2307/1523154, JSTOR 1523154

- Woodman, Francis; Bloom, Jonathan M. (2003). "Arch". Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t003657. ISBN 978-1-884446-05-4.

Further reading

[edit]- Viollet-Le-Duc, Eugene. Dictionnaire raisonné de l'architecture française du XIe au XVIe siècle (in French). (in nine volumes)

![New Peterhof railway station [ru], Peterhof, Russia (1857)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/ca/%D0%A1%D1%82%D0%B0%D0%BD%D1%86%D0%B8%D1%8F_%D0%9D%D0%BE%D0%B2%D1%8B%D0%B9_%D0%9F%D0%B5%D1%82%D0%B5%D1%80%D0%B3%D0%BE%D1%84_-1.jpg/500px-%D0%A1%D1%82%D0%B0%D0%BD%D1%86%D0%B8%D1%8F_%D0%9D%D0%BE%D0%B2%D1%8B%D0%B9_%D0%9F%D0%B5%D1%82%D0%B5%D1%80%D0%B3%D0%BE%D1%84_-1.jpg)