Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Headline

View on WikipediaThe headline is the text indicating the content or nature of the article below it, typically by providing a form of brief summary of its contents.

The large type front page headline did not come into use until the late 19th century when increased competition between newspapers led to the use of attention-getting headlines.

It is sometimes termed a news hed, a deliberate misspelling that dates from production flow during hot type days, to notify the composing room that a written note from an editor concerned a headline and should not be set in type.[1]

Headlines in English often use a set of grammatical rules known as headlinese, designed to meet stringent space requirements by, for example, leaving out forms of the verb "to be" and choosing short verbs like "eye" over longer synonyms like "consider".

Production

[edit]

A headline's purpose is to quickly and briefly draw attention to the story. It is generally written by a copy editor, but may also be written by the writer, the page layout designer, or other editors. The most important story on the front page above the fold may have a larger headline if the story is unusually important. The New York Times's 21 July 1969 front page stated, for example, that "MEN WALK ON MOON", with the four words in gigantic size spread from the left to right edges of the page.[2]

In the United States, headline contests are sponsored by the American Copy Editors Society, the National Federation of Press Women, and many state press associations; some contests consider created content already published,[3] others are for works written with winning in mind.[4]

Typology

[edit]Research in 1980 classified newspaper headlines into four broad categories: questions, commands, statements, and explanations.[5] Advertisers and marketers classify advertising headlines slightly differently into questions, commands, benefits, news/information, and provocation.[6]

Research

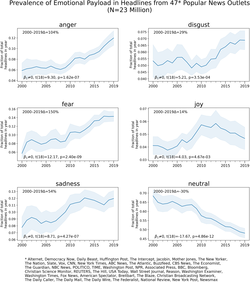

[edit]A study indicates there has been a substantial increase of sentiment negativity and decrease of emotional neutrality in headlines across written popular U.S.-based news media since 2000.[8][7]

Another study concluded that those who have gained the most experience with reading newspapers "spend most of their reading time scanning the headlines—rather than reading [all or most of] the stories".[9]

Headlines can bias readers toward a specific interpretation and readers struggle to update their memory in order to correct initial misconceptions in the cases of misleading or inappropriate headlines.[10]

One approach investigated as a potential countermeasure to online misinformation is "attaching warnings to headlines of news stories that have been disputed by third-party fact-checkers", albeit its potential problems include e.g. that false headlines that fail to get tagged are considered validated by readers.[11]

Criticism

[edit]Sensationalism, inaccuracy and misleading headlines

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2022) |

"Slam"

[edit]The use of "slam" in headlines has attracted criticism on the grounds that the word is overused and contributes to media sensationalism.[12][13] The violent imagery of words like "slam", "blast", "rip", and "bash" has drawn comparison to professional wrestling, where the primary aim is to titillate audiences with a conflict-laden and largely predetermined narrative, rather than provide authentic coverage of spontaneous events.[14]

Crash blossoms

[edit]"Crash blossoms" is a term used to describe headlines that have unintended ambiguous meanings, such as The Times headline "Hospitals named after sandwiches kill five". The word 'named' is typically used in headlines to mean "blamed/held accountable/named [in a lawsuit]",[15] but in this example it seems to say that the hospitals' names were related to sandwiches. The headline was subsequently changed in the electronic version of the article.[16] The term was coined in August 2009 on the Testy Copy Editors web forum[17] after the Japan Times published an article entitled "Violinist Linked to JAL Crash Blossoms"[18] (since retitled to "Violinist shirks off her tragic image").[19]

Headlinese

[edit]

Headlinese is an abbreviated form of news writing style used in newspaper headlines.[20] Because space is limited, headlines are written in a compressed telegraphic style, using special syntactic conventions,[21] including:

- Forms of the verb "to be" and articles (a, an, the) are usually omitted.

- Most verbs are in the simple present tense, e.g. "Governor signs bill", while the future is expressed by an infinitive, with to followed by a verb, as in "Governor to sign bill"

- The conjunction "and" is often replaced by a comma, as in "Bush, Blair laugh off microphone mishap".[22]

- Individuals are usually specified by surname only, with no honorifics.

- Organizations and institutions are often indicated by metonymy: "Wall Street" for the US financial sector, "Whitehall" for the UK government administration, "Madrid" for the government of Spain, "Davos" for World Economic Forum, and so on.

- Many abbreviations, including contractions and acronyms, are used: in the UK, some examples are Lib Dems (for the Liberal Democrats), Tories (for the Conservative Party); in the US, Dems (for "Democrats") and GOP (for the Republican Party, from the nickname "Grand Old Party"). The period (full point) is usually omitted from these abbreviations, though U.S. may retain them, especially in all-caps headlines to avoid confusion with the word us.

- Lack of a terminating full stop (period) even if the headline forms a complete sentence.

- Use of single quotation marks to indicate a claim or allegation that cannot be presented as a fact. For example, an article titled "Ultra-processed foods 'linked to cancer'" covered a study which suggested a link but acknowledged that its findings were not definitive.[23][24] Linguist Geoffrey K. Pullum characterizes this practice as deceptive, noting that the single-quoted expressions in newspaper headlines are often not actual quotations, and sometimes convey a claim that is not supported by the text of the article.[25] Another technique is to present the claim as a question, hence Betteridge's law of headlines.[23][26]

Some periodicals have their own distinctive headline styles, such as Variety and its entertainment-jargon headlines, most famously "Sticks Nix Hick Pix".

Commonly used short words

[edit]To save space and attract attention, headlines often use extremely short words, many of which are not otherwise in common use, in unusual or idiosyncratic ways:[27][28][29]

- ace (a professional, especially a member of an elite sports team, e.g. "England ace")

- axe (to eliminate)

- bid (to attempt)

- blast (to heavily criticize)

- cagers (basketball team – "cage" is an old term for indoor court)[30]

- chop (to eliminate)

- coffer(s) (a person or entity's financial holdings)

- confab (a meeting)[citation needed]

- eye (to consider)

- finger (to accuse, blame)

- fold (to shut down)

- gambit (an attempt)

- hail (to praise, welcome)

- hike (to increase, raise)

- ink (to sign a contract)

- jibe (an insult)

- laud (to praise)

- lull (a pause)

- mar (to damage, harm)

- mull (to contemplate)

- nab (to acquire, arrest)

- nix (to reject)

- parley (to discuss)

- pen (to write)

- probe (to investigate)

- quiz (to question, interrogate)

- rap (to criticize)

- romp (an easy victory or a sexual encounter)

- row (an argument or disagreement)

- rue (to lament)

- see (to forecast)

- slay (to murder)

- slam (to heavily criticize)

- slump (to decrease)

- snub (to reject)

- solon (to judge)

- spat (an argument or disagreement)

- spark (to cause, instigate)

- star (a celebrity, often modified by another noun, e.g. "soap star")

- tap (to select, choose)

- tot (a child)

- tout (to put forward)

- woe (disappointment or misfortune)

Famous examples

[edit]- "Wall Street Lays an Egg" – Variety employing the idiom lay an egg (meaning "fail badly") at the height of the Wall Street crash (1929)

- "Sticks Nix Hick Pix" – Variety writing that rural moviegoers preferred urban films (1935)

- "Dewey Defeats Truman" – Chicago Tribune incorrectly reporting the winner of the U.S. presidential election (1948)

- "Ford to City: Drop Dead" – New York Daily News reporting the denial of a federal bailout for bankrupt New York City (1975)

- "Mush from the Wimp" – The Boston Globe editorial criticizing statements from then-president Jimmy Carter, added by staff as a joke and mistakenly printed (1980)[31]

- "Headless Body in Topless Bar" – New York Post on a local murder (1983)[32]

- "Sick Transit's Glorious Monday" – New York Daily News reporting an agreement to avoid public transit fare increases, a pun on the Latin phrase sic transit gloria mundi meaning "thus passes the glory of the world" (1979)[33]

- "Gotcha" – The UK Sun on the torpedoing of the Argentine ship Belgrano and sinking of a gunboat during the Falklands War (1982)

- "Freddie Starr Ate My Hamster" – The UK Sun claiming that the comedian had eaten a fan's pet hamster in a sandwich, later proven false (1986)[34]

- "Great Satan Sits Down with the Axis of Evil" – The Times (UK) on US–Iran talks (2007)[35]

- "Super Caley Go Ballistic, Celtic are Atrocious" – Sun on Caley Thistle beating Celtic F.C. in the Scottish Cup, a pun on supercalifragilisticexpialidocious (2000)[36]

- "We are Pope!" (in German: Wir sind Papst!) – Bild on the election of Pope Benedict XVI, a German (2005)

In 1986, The New Republic editor Michael Kinsley held a contest to find the most boring newspaper headline after seeing "Worthwhile Canadian Initiative" over a New York Times column by Flora Lewis.[37][38][39] He reported being "absolute comatose with appreciation" for submissions, such as "Economist Dies" in the Wisconsin State Journal and "Prevent Burglary by Locking House, Detectives Urge" in the Boston Globe. In 2003, New York Magazine published a list of eleven "greatest tabloid headlines".[40]

On 22 June 1978, The Guardian ran an article with the headline "Foot hits back on Nazi comparison".[41] Reader David C. Allan of Edinburgh responded with a letter to the editor, which the paper ran on 27 June. Decrying the headline's apparent pun, Allan suggested that, if Foot were in future to be appointed Secretary of State for Defence, The Guardian might cover it under the headline "Foot Heads Arms Body".[42] The belief later gained currency that The Times actually had run the headline.[43] The headline does not, however, appear in The Times Digital Archive.[44]

See also

[edit]- A-1 Headline, a 2004 Hong Kong film

- Betteridge's law of headlines – Journalistic adage on questions in headlines

- Bus plunge, a type of news story, and accompanying headline

- Copy editing

- Corporate jargon

- Crosswordese, words common in crosswords that are otherwise rarely used

- Dateline – Piece of news text

- Ellipsis (linguistics), omission of words

- Headlines (from The Tonight Show with Jay Leno)

- Lead paragraph

- Nut paragraph – In journalism, an opening paragraph providing context for the story

- Syntactic ambiguity, leads to multiple humorous possible alternative interpretations of written headline

- Title (publishing) – Name of a published text or work of art

References

[edit]- ^ NY Times: On Language: HED

- ^ Wilford, John Noble (14 July 2009). "On Hand for Space History, as Superpowers Spar". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- ^ "Headline Contest".

- ^ A NYTimes contest to write a NYPost-style headline"After Winning N.Y. Times Contest". The New York Times. November 11, 2011.

- ^ Davis & Brewer 1997, p. 56.

- ^ Arens 1996, p. 285.

- ^ a b c Rozado, David; Hughes, Ruth; Halberstadt, Jamin (18 October 2022). "Longitudinal analysis of sentiment and emotion in news media headlines using automated labelling with Transformer language models". PLOS ONE. 17 (10) e0276367. Bibcode:2022PLoSO..1776367R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0276367. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 9578611. PMID 36256658.

- ^ Brooks, David (27 October 2022). "Opinion | The Rising Tide of Global Sadness". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ^ Dor, Daniel (May 2003). "On newspaper headlines as relevance optimizers". Journal of Pragmatics. 35 (5): 695–721. doi:10.1016/S0378-2166(02)00134-0. S2CID 8394655.

- ^ Ecker, Ullrich K. H.; Lewandowsky, Stephan; Chang, Ee Pin; Pillai, Rekha (December 2014). "The effects of subtle misinformation in news headlines". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied. 20 (4): 323–335. doi:10.1037/xap0000028. PMID 25347407.

- ^ Pennycook, Gordon; Bear, Adam; Collins, Evan T.; Rand, David G. (November 2020). "The Implied Truth Effect: Attaching Warnings to a Subset of Fake News Headlines Increases Perceived Accuracy of Headlines Without Warnings". Management Science. 66 (11): 4944–4957. doi:10.1287/mnsc.2019.3478.

- ^ Ann-Derrick Gaillot (2018-07-28). "The Outline "slams" media for overusing the word". The Outline. Retrieved 2020-02-24.

- ^ Kehe, Jason (9 September 2009). "Colloquialism slams language". Daily Trojan.

- ^ Russell, Michael (8 October 2019). "Biden 'Rips' Trump, Yankees 'Bash' Twins: Is Anyone Going to 'Slam' the Press?". PolitiChicks. Archived from the original on 28 September 2022. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- ^ Pérez, Isabel. "Newspaper Headlines". English as a Second or Foreign Language. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ^ Brown, David (18 June 2019). "Hospital trusts named after sandwiches kill five". The Times. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ^ Zimmer, Ben (Jan 31, 2010). "Crash Blossoms". New York Times Magazine. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ^ subtle_body; danbloom; Nessie3. "What's a crash blossom?". Testy Copy Editors. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Masangkay, May (18 August 2009). "Violinist shirks off her tragic image". The Japan Times. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ^ Headlinese Collated definitions via www.wordnik.com

- ^ Isabel Perez.com: "Newspaper Headlines"

- ^ "Bush, Blair laugh off microphone mishap". CNN. July 21, 2006. Archived from the original on August 16, 2007. Retrieved July 17, 2007.

- ^ a b Pack, Mark (2020). Bad News: What the Headlines Don't Tell Us. Biteback. p. 100-102.

- ^ "Ultra-processed foods 'linked to cancer'". BBC News. 2018-02-15. Retrieved 2021-02-26.

- ^ Pullum, Geoffrey (2009-01-14). "Mendacity quotes". Language Log. Retrieved 2021-02-26.

- ^ "The Secrets You Learn Working at Celebrity Gossip Magazines". 2018-09-12. Retrieved 2021-02-26.

- ^ Chad Pollitt (March 5, 2019). "Which Types of Headlines Drive the Most Content Engagement Post-Click?". Social Media Today.

- ^ "19 Headline Writing Tips for More Clickable Blog Posts". August 27, 2019.

- ^ Ash Read (August 24, 2016). "There's No Perfect Headline: Why We Need to Write Multiple Headlines for Every Article".

- ^ "When the Court was a Cage" Archived 2019-11-05 at the Wayback Machine, Sports Illustrated

- ^ Scharfenberg, Kirk (1982-11-06). "Now It Can Be Told . . . The Story Behind Campaign '82's Favorite Insult". The Boston Globe. Boston, Massachusetts. p. 1. Archived from the original on 2011-05-23. Retrieved 2011-01-20.(subscription required)

- ^ Fox, Margalit (2016-06-09). "Vincent Musetto, 74, Dies; Wrote 'Headless' Headline of Ageless Fame". The New York Times.

- ^ Daily News (New York), 9/25/1979, p. 1

- ^ "Telegraph wins newspaper vote". BBC News. 25 May 2006.

- ^ Great Satan sits down with the Axis of Evil[dead link]

- ^ "Super Caley dream realistic?". BBC. 22 March 2003.

- ^ Lewis, Flora (4 October 1986). "Worthwhile Canadian Initiative". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- ^ Kinsley, Michael (1986-06-02). "Don't Stop The Press". The New Republic. Retrieved April 26, 2011.

- ^ Kinsley, Michael (28 July 2010). "Boring Article Contest". The Atlantic. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ^ "Greatest Tabloid Headlines". Nymag.com. March 31, 2003. Archived from the original on January 22, 2009. Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- ^ "Foot hits back on Nazi comparison". The Guardian. 22 June 1978.

- ^ Allan, David C. (1978-06-27). "Footnote [letter to the editor]". The Guardian. p. 10.

- ^ Hoggart, Simon (5 March 2010). "Footnotes to a life well lived". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- ^ "The Times Digital Archive". Cengage Learning. 2011. Archived from the original on 30 April 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

Works cited

[edit]- Arens, William F. (1996). Contemporary Advertising. Irwin. ISBN 978-0-256-18257-6.

- Davis, Boyd H.; Brewer, Jeutonne (1 January 1997). Electronic Discourse: Linguistic Individuals in Virtual Space. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-3475-8.

news headlinesHeadlines

Further reading

[edit]- Harold Evans (1974). News Headlines (Editing and Design : Book Three) Butterworth-Heinemann Ltd. ISBN 978-0-434-90552-2

- Fritz Spiegl (1966). What The Papers Didn't Mean to Say. Scouse Press, Liverpool ISBN 0901367028

- Mårdh, Ingrid (1980); Headlinese: On the Grammar of English Front Page headlines; "Lund studies in English" series; Lund, Sweden: Liberläromedel/Gleerup; ISBN 91-40-04753-9

- Biber, D. (2007); "Compressed noun phrase structures in newspaper discourse: The competing demands of popularization vs. economy"; in W. Teubert and R. Krishnamurthy (eds.); Corpus linguistics: Critical concepts in linguistics; vol. V, pp. 130–141; London: Routledge

External links

[edit]- Front Page – The British Library Archived 2017-07-22 at the Wayback Machine Exhibition of famous newspaper headlines

Headline

View on GrokipediaHistory

Origins and Early Development

The practice of headline writing originated with the earliest printed news publications in Europe, particularly news broadsides and pamphlets that emerged in Germany in the late 1400s. These single-sheet publications often featured bold, sensationalized titles designed to capture immediate interest amid limited literacy and distribution challenges, serving as precursors to modern headlines by summarizing key events or rumors in concise, attention-grabbing phrases.[10] As weekly newspapers developed in the early 17th century—beginning with German publications around 1605—headlines began to evolve from mere titles on broadsides into structured labels for individual articles within multi-column formats. Early examples were modest, typically in larger type above dense text blocks, prioritizing factual indexing over dramatic appeal due to governmental censorship and small audiences; for instance, English corantos from the 1620s used simple declarative phrases to denote foreign news dispatches.[11] In colonial America, by the mid-18th century, newspapers like the Boston News-Letter (1704) employed rudimentary headlines to separate reports, reflecting the influence of European models while adapting to local printing constraints such as hand-operated presses limited to four pages.[12] The early 19th century marked significant development with technological advances, including steam-powered presses introduced around 1814, which enabled larger editions and mass production, necessitating headlines for efficient content navigation. The penny press era, starting with the New York Sun in 1833, accelerated this by targeting working-class readers via street sales, prompting editors to craft more vivid, sales-oriented headlines—often one- or two-line summaries emphasizing novelty or conflict—to boost impulse purchases amid rising competition.[4] By the 1840s, revolving presses further facilitated multi-column layouts, allowing stacked "decks" of headlines that teased story content while conserving space in affordable four-page dailies.[13] This period saw headlines shift from neutral descriptors to promotional tools, though still restrained compared to later sensationalism, as evidenced in antebellum U.S. papers where front-page articles routinely carried bolded titles amid inconsistent typography.[14]Evolution in Print Era

In the early print era, from the 17th to mid-19th centuries, newspapers typically lacked distinct headlines, with articles commencing directly after the masthead and dateline in a continuous block of text. This format prioritized dense information delivery over visual hierarchy, reflecting the hand-composed, labor-intensive production methods of the time.[15] The introduction of more prominent headlines emerged during the American Civil War (1861–1865), where typesetters innovated large, capitalized display lines and varied fonts to capture reader attention amid urgent war dispatches enabled by the telegraph. Post-war, editors refined these styles for aesthetic appeal, coinciding with technological advances like steam-powered presses that allowed for faster production and larger editions. By the late 19th century, competition intensified with the rise of the penny press in the 1830s, which democratized access and spurred circulations into the tens of thousands, necessitating headlines as tools for differentiation.[16][4] Yellow journalism, epitomized by Joseph Pulitzer's New York World (circulation over 600,000 by 1898) and William Randolph Hearst's New York Journal, accelerated headline sensationalism in the 1890s. These publishers employed exaggerated, attention-grabbing banners—such as those accusing Spain after the USS Maine explosion in Havana harbor on February 15, 1898—to fuel public outrage and boost sales during the Spanish-American War. This era marked a shift from informational summaries to emotionally charged declarations, driven by profit motives and mass market demands rather than strict factual restraint.[17][18] By the early 20th century, multicolumn headlines spanning front pages became standard, as seen in coverage of events like World War I armistices, enabling newspapers to visually compete on urban newsstands and align with advertising revenue models. This evolution reflected causal pressures from technological scalability, competitive economics, and reader psychology, prioritizing brevity and impact over exhaustive detail, laying groundwork for headlinese conventions like omitted articles and active verbs.[4][16]Adaptations in Digital and Online Media

In digital and online media, news headlines have shifted from the concise, space-constrained formats of print to longer, engagement-optimized structures driven by search engine optimization (SEO), social media algorithms, and click-through rate (CTR) metrics. Unlike print headlines, which prioritize brevity to fit physical layouts, online headlines expanded in length by approximately 0.25 words per year from 2000 onward, enabling inclusion of descriptive keywords and narrative elements to improve visibility in search results and social feeds.[19] This adaptation reflects the removal of column-inch limits, allowing headlines to function as standalone previews in digital environments where users scan aggregated content.[20] Linguistic features evolved toward clickbait-like elements, including increased use of pronouns, wh-words (e.g., "what," "how"), active verbs, and question forms, which correlate with higher CTRs across diverse outlets.[19] Negativity in headlines rose consistently over two decades, with negative sentiment increasing while positive declined, a trend observed in analyses of nearly 40 million English-language headlines regardless of outlet quality or political lean.[20] These changes stem from low production costs, real-time audience feedback via A/B testing, and competition in an attention economy, where headlines must entice clicks amid algorithm-driven distribution.[19] SEO strategies further shaped headlines, emphasizing keyword integration to match user queries, with optimal lengths around 55-60 characters to avoid truncation in search displays.[21] Social media platforms amplified this by favoring sensational or emotional content, as negative headlines receive more shares and engagement, prompting outlets to tailor versions for platforms like Facebook, often shortening or remediating originals for virality.[22] [23] Analytics tools enable iterative testing, but this focus on metrics has raised concerns over sensationalism eroding trust, though empirical data shows such features persist due to measurable traffic gains.[19]Production and Techniques

Core Principles of Headline Writing

Headlines in journalism serve as the primary entry point to a story, encapsulating its essence while adhering to standards of factual integrity and reader utility. Core principles emphasize accuracy, ensuring the headline faithfully represents the article's content without exaggeration or omission that could mislead; for instance, Reuters journalistic standards mandate that headlines avoid distortion, prioritizing verifiable facts over interpretive spin.[24] This principle stems from the causal imperative that deceptive headlines erode public trust, as evidenced by editorial guidelines from institutions like Northwestern University, which require headlines to derive solely from the body's information.[25] Brevity constitutes another foundational rule, constraining headlines to 5-10 words to fit spatial limits in print and attentional thresholds in digital formats; longer phrases dilute impact and reduce click-through rates, per analyses of newsroom practices.[26] Journalistic handbooks, such as those from the Defense Information School, instruct writers to summarize the story in one line using present tense and active voice, eliminating superfluous articles and prepositions to achieve telegraphic efficiency.[27] This concision aligns with empirical observations that shorter headlines enhance scannability amid information overload, without sacrificing substantive detail. Clarity demands straightforward language accessible to a broad audience, eschewing jargon, puns, or ambiguity that might obscure meaning; the "ABCs" of journalism—accuracy, brevity, clarity—codify this as a triad for effective communication, as outlined in university writing centers.[28] For example, active verbs and specific nouns prioritize reader comprehension over stylistic flair, contrasting with marketing headlines that may favor intrigue at clarity's expense.[29] Reuters reinforces this by prohibiting bias or opinion in headlines, ensuring neutrality through precise phrasing grounded in sourced events.[30] Additional principles include informativeness, where headlines must signal the story's news value—who, what, when, where, why—without introducing unsubstantiated claims, and engagement, achieved via strong, concrete words that arouse curiosity ethically rather than through clickbait tactics that violate trust principles.[31] These tenets, upheld across editorial processes, mitigate risks of misinformation, as seen in standards from the Society of Professional Journalists advocating against emphasis-driven distortion.[32] Violations, such as sensationalism, have historically prompted corrections, underscoring the causal link between principled writing and sustained credibility.[24]Tools, Constraints, and Editorial Processes

Headline writers in journalism rely on a combination of manual techniques and digital tools to produce concise, impactful titles. Traditionally, tools include style guides such as the Associated Press (AP) Stylebook, which provides rules for capitalization, numerals, and phrasing in headlines, such as using sentence case, present tense, and avoiding articles or conjunctions unless essential.[33] In digital environments, software like headline analyzers evaluates emotional impact, SEO potential, and readability, while AI tools such as Grammarly's headline generator or Jasper assist in generating drafts and variations to test engagement.[34][35] Key constraints shape headline creation, primarily brevity and spatial limits: print headlines are measured in "counts" (character units per line) to fit column widths, often capped at 25-30 counts, demanding telegraphic language without filler words.[36] Digital headlines face character limits for search engine display (e.g., 70 characters for Google) and must incorporate keywords for algorithmic visibility while avoiding clickbait that misrepresents content.[31] Accuracy is paramount, as headlines must summarize the story without exaggeration or new facts, per ethical guidelines to prevent deception or legal risks like libel.[25] Style adherence, such as AP's preference for active verbs and numerals over spelled-out numbers, further restricts phrasing to maintain consistency across outlets.[37] Editorial processes typically begin with reporters submitting stories, after which copy editors draft multiple headline options based on a full reading to capture core elements like who, what, and why.[27] Drafts undergo review by assigning or slot editors for factual alignment, tone suitability, and house style compliance, with revisions to mitigate bias or sensationalism.[38] In digital newsrooms, processes may include A/B testing post-publication using analytics tools to assess click-through rates, prompting swaps for underperforming variants, though initial approvals prioritize journalistic integrity over metrics.[39] Senior editorial oversight escalates for high-stakes stories to ensure headlines withstand scrutiny from diverse audiences.[40]Classification and Typology

Informational and Declarative Types

Informational and declarative headlines convey the essential facts of a news story through straightforward statements, often structured as complete or telegraphic sentences that summarize key elements such as the subject, action, and context. These headlines employ a subject-verb or subject-verb-object format to deliver information efficiently, typically in the present tense to imply immediacy and relevance.[31][41] Distinguished from interrogative or imperative forms, declarative headlines assert rather than question or command, fostering an impression of objectivity and reliability suitable for hard news reporting. For instance, a headline like "Federal Reserve Raises Interest Rates by 0.25%" directly informs readers of the event and its scale without eliciting speculation.[42] Such constructions avoid auxiliary verbs, articles, and infinitives to maximize brevity while retaining grammatical coherence, adhering to conventions that prioritize factual density over stylistic flair. Informational variants emphasize unadorned reporting of verifiable details, serving as the default for straight news where the story's intrinsic value drives readership rather than engineered intrigue.[43] Empirical studies indicate these headlines align with traditional journalistic standards of accuracy but yield lower click-through rates in digital environments compared to question-based alternatives; one field experiment across online articles found declarative formats generated 14-29% fewer engagements, attributed to reduced curiosity arousal.[44][45] Despite this, they maintain higher perceived credibility among audiences valuing substance over sensationalism, particularly in contexts demanding causal transparency like policy or economic updates. In practice, these types dominate print-era front pages for events of broad significance, such as "Armistice Signed Ending World War I" in the New York Times on November 11, 1918, which encapsulated the outcome without embellishment. Their declarative nature supports rapid comprehension, enabling readers to assess relevance at a glance, though editorial constraints like space limits—often 5-10 words—necessitate omission of qualifiers to fit column widths.[41] Over-reliance on them in biased outlets can still propagate selective framing, underscoring the need for cross-verification against primary data sources.Expressive, Question, and Command Types

Expressive headlines, often aligning with exclamatory sentence structures, emphasize emotional intensity or rhetorical emphasis to evoke reader reaction, such as surprise, outrage, or triumph.[46] These differ from neutral declarative forms by prioritizing affective impact over factual summation, frequently employing exclamation points or hyperbolic phrasing in informal or tabloid journalism. For instance, historical examples include "WOMAN MYSTERY-DEATH VICTIM!" from early 20th-century U.S. newspapers, which amplified drama to boost circulation.[47] Empirical analysis of headline sentiment since 2000 shows rising emotionality in digital-era news, correlating with increased reader engagement metrics, though critics argue this fosters sensationalism over substance. ![Emotionality in news articles headlines since 2000.png][center] Question headlines, or interrogative types, pose direct queries to stimulate curiosity and prompt article consumption by implying unresolved intrigue.[49] Common in feature and online journalism, they leverage psychological gaps in reader knowledge, as seen in examples like "Why Do You Need a Will?" from legal advocacy pieces.[50] Studies indicate question formats outperform declarative ones in click-through rates by 20-30% on digital platforms, attributed to mirroring natural inquisitiveness, yet they risk misleading if the article fails to resolve the posed issue substantively.[51] In news contexts, such headlines surged post-2010 with algorithmic news feeds prioritizing engagement signals over informational value.[49] Command headlines adopt imperative grammar to direct reader action, typically appearing in promotional, editorial calls-to-action, or advocacy journalism rather than straight reporting.[52] Phrases like "Buy This EBook Now!" exemplify the form, starting with a verb to compel immediate response, rooted in direct-response advertising principles adapted to headlines.[53] Usage in news is limited to opinion sections or campaigns, such as "Vote Yes on Proposition 1!" during elections, where efficacy depends on audience alignment; mismatched commands can provoke backlash, reducing credibility.[49] Data from content optimization platforms reveal command types yield higher conversion rates in targeted ads but underperform in general news feeds due to perceived pushiness.[54]Linguistic Features

Headlinese Conventions and Abbreviations

Headlinese, the specialized language of newspaper and media headlines, relies on a telegraphic style that prioritizes brevity through systematic omissions and grammatical simplifications. Function words such as articles ("a," "an," "the") and auxiliary verbs (including forms of "to be") are routinely excluded to reduce word count while preserving core meaning.[55][56] For instance, a full sentence like "The president has signed the bill" becomes "President Signs Bill."[55] Headlinese frequently uses passive voice, often omitting the auxiliary verb "be" for brevity, to emphasize the recipient of the action or the event itself, or to omit the agent when it is unknown or unimportant. Examples include: "Obama elected president for second term" (implying "Obama was elected"); "Toronto named 'most youthful' city in world" ("Toronto was named"); "Two baby baboons born at Brooklyn zoo" ("Two baby baboons were born"); "World's Biggest Bookstore sold to developer" ("was sold"); "2000 workers laid off by Ford motor company last month" ("2000 workers were laid off"); "Mistakes were made" (obscuring agency); and "The suspect was shot" (hiding who shot the suspect).[57][58] Verbs in headlinese favor the simple present tense to convey past events, creating a sense of immediacy and timelessness, as in "Team Wins Championship" for a completed match.[59][56] Future-oriented headlines employ the infinitive form without "to," such as "Team to Play Final," and coordinating conjunctions like "and" are dropped when space is limited.[56] Short synonyms replace longer terms for concision—"clash" for "disagree" or "vie" for "compete"—and noun stacking juxtaposes multiple nouns without prepositions or articles, yielding structures like "School Coach Crash Drama."[59] Abbreviations in headlinese further compress information, primarily through clippings (shortened words like "Mum" for Mumbai or "Ash" for Aishwarya), initialisms (letter-by-letter forms such as "PC" for Police Commissioner or "NZ" for New Zealand), and blends (merged terms like "SanTina" for tennis players Sania Mirza and Martina Hingis).[60] Clippings and shortenings constitute the most frequent types, comprising about 36% and 30% respectively in analyzed samples, serving to accelerate reading and fit spatial limits in print layouts.[60] Journalistic style guides, such as the Associated Press, caution against overuse, permitting only widely familiar acronyms like "FBI," "EU," or "US" to avoid confusion, while advising against state abbreviations unless contextually essential.[61][37] In practice, abbreviations for names and places persist in tabloid and digital formats for punchiness, though they risk ambiguity if not intuitive.[60]Stylistic Devices for Brevity and Impact

News headlines utilize rhetorical and literary devices to achieve conciseness while amplifying emotional and cognitive appeal, enabling rapid information transmission in limited space. These techniques, rooted in linguistic economy, prioritize active verbs, nominalization, and figurative language over verbose exposition, as evidenced by corpus analyses of English-language headlines showing preferences for structures that omit auxiliary verbs and articles to fit column widths typically under 10 words.[62][63] Alliteration, the repetition of initial consonant sounds, enhances memorability and rhythm without adding length; for example, phrases like "Panic Buying Paralyses Paris" employ this device to foreground urgency in disaster coverage, correlating with increased reader retention in empirical studies of headline efficacy.[64][65] Assonance and consonance similarly provide sonic impact, as in "Storm Surge Swamps Streets," compressing descriptive power into phonetic patterns that mimic the event's intensity.[66] Figurative devices such as metaphor and metonymy substitute concrete images for abstract concepts, fostering brevity by evoking associations instantaneously; metonymy, the most prevalent in national newspaper samples, replaces entities with attributes like "White House Denies Claims" for the U.S. presidency, reducing syllables while implying authority.[67][65] Personification attributes human qualities to non-humans, as in "Market Meltdown Eats Savings," personifying economic forces to heighten drama and relatability in financial reporting.[68][69] Hyperbole exaggerates scale for emphasis, such as "Apocalypse Now: Floods Devastate Continent," which, while risking overstatement, drives attention in competitive media environments, per analyses of expressive headline typology.[68][70] Antithesis contrasts ideas sharply, like "Boom to Bust in Blink," juxtaposing extremes to underscore volatility succinctly.[71] Rhetorical questions engage directly, e.g., "Can Democracy Survive?", prompting inference and curiosity without declarative assertion, a tactic frequent in BBC and CNN headlines for eliciting behavioral responses like clicks.[69][72] Puns and irony leverage ambiguity for layered meaning, as in "Oil Spill: Slick Move by Negligent Firm," critiquing corporate error wittily to sustain interest amid brevity demands; such wordplay, though less quantifiable, appears in stylistic inventories of impactful headlines.[68][73] Empirical corpus work indicates these devices cluster in high-engagement contexts, balancing informational density with persuasive pull, though overuse can erode trust if perceived as manipulative.[74][62]Empirical Research

Studies on Readability and Comprehension

Empirical research demonstrates that online news readers consistently prefer simpler headlines, characterized by higher readability scores and more common vocabulary, over complex alternatives. A large-scale analysis involving approximately 30,000 A/B tests with The Washington Post (7,371 experiments across 19,926 headlines) and Upworthy (22,664 experiments across 105,551 headlines) found positive correlations between headline simplicity—measured via metrics like the Flesch Reading Ease score, Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC) for word frequency and analytic style, and character length—and engagement outcomes such as click-through rates (r=0.055, P<0.001) and clicks per impression (r=0.022, P<0.001).[75] In controlled choice tasks, general readers selected simpler headlines with an odds ratio of 2.83 (P<0.001), indicating enhanced accessibility and potential for initial comprehension, whereas journalists showed no preference, highlighting a producer-consumer mismatch in evaluating readability.[75] Studies on headline effects extend to comprehension and recall, revealing that journalistic conventions may not optimize retention. Two experiments with over 300 participants across age and educational groups (including high school students, undergraduates, and journalism students) compared reading conditions: full articles (headline + summary + text), headline + text, summary + text, and text only. Results indicated no significant impact from headline presence on immediate or delayed free recall compared to text-only exposure, though group differences in recall volume and accuracy emerged based on reader expertise.[76] However, when headlines were experimentally modified to better align with macrostructural content organization, recall improved relative to unmodified journalistic versions, suggesting that standard headline practices prioritize brevity over comprehensive signaling of article themes.[76] Investigations into headline accuracy further illuminate comprehension risks, particularly for inferential processing. In a between-subjects study of 138 undergraduates exposed to news articles on topics like solitary confinement, stem cell research, and wildfires, congruent (accurate) headlines yielded no overall memory advantage over incongruent (misleading) ones, with recognition scores averaging 4.11 (SD=1.35) versus 4.09 (SD=1.32; t(136)=0.115, p=0.909).[77] Inferential reasoning, however, suffered under misleading headlines for certain content, such as stem cell articles (mean scores 1.83 vs. 1.65; F(1,136)=4.124, p=0.044), implying that headline-reader incongruence can distort higher-order understanding despite intact factual recall, though effects were mitigated by enforced reading time.[77] Readability's role in broader comprehension heuristics, such as credibility assessment, appears limited. An experimental probe into whether easier-to-read headlines enhance perceived news trustworthiness found no such effect, challenging assumptions that linguistic simplicity cues reliability for consumers.[78] Collectively, these findings underscore headlines' dual function in attracting attention via simplicity while risking comprehension gaps from stylistic shortcuts or mismatches, with implications for journalistic training to bridge readability preferences and cognitive outcomes.Investigations into Engagement and Behavioral Effects

Studies have demonstrated that negative sentiment in news headlines significantly boosts user engagement metrics, such as click-through rates (CTR). For instance, an analysis of over 46,000 headlines from a major online news outlet found that each additional negative word increased CTR by 2.3%, while positive words decreased it by a comparable margin, controlling for headline length and topic.[79] This negativity bias aligns with evolutionary preferences for threat detection, driving higher consumption of alarming content over neutral or positive alternatives.[80] Clickbait headlines, characterized by exaggerated promises or information gaps, yield mixed effects on engagement. Experimental research indicates they can elevate initial clicks but often fail to sustain deeper interaction, such as prolonged reading time or shares, particularly in domains like health news where emotional intensity may deter dissemination due to perceived unreliability.[81] [82] In contrast, large-scale A/B testing across headlines revealed that features like personalization or curiosity induction inconsistently outperform straightforward formulations, with overall CTR gains modest and context-dependent.[83] Behavioral impacts extend to sharing and trust dynamics. Negative or sensational headlines, including those framed as "breaking news," amplify sharing on social media, as users propagate high-arousal content to signal vigilance or evoke reactions, though this erodes long-term credibility perceptions.[22] [84] Peer-reviewed analyses confirm that emotionally charged negative headlines from biased sources spread further, fostering polarization by reinforcing selective exposure, whereas positive sentiment correlates with reduced virality.[85] These patterns suggest headlines shape not just immediate clicks but habitual news-seeking behaviors, prioritizing novelty over accuracy.[7]Criticisms and Controversies

Sensationalism, Clickbait, and Negativity Bias

![Average yearly sentiment of headlines across 47 popular news media outlets][float-right]Sensationalism in news headlines involves the use of exaggerated, emotionally charged language to attract attention, often at the expense of factual nuance or context.[86] This practice has historical roots but intensified with digital media's reliance on ad revenue tied to page views. Empirical analysis of U.S. news outlets reveals a marked rise in sensational features like forward referencing and personalization in headlines from digitally native versus legacy media, with online-native sites employing such tactics up to 20% more frequently to boost virality.[87] Clickbait represents a modern variant, crafting misleading or hyperbolic titles to provoke clicks while underdelivering in content, prevalent across both mainstream and unreliable outlets. Research tracking English-language media from 2014 to 2016 documented a surge in clickbait usage, correlating with algorithmic amplification on platforms like social media.[88] Experimental studies confirm clickbait headlines enhance initial engagement metrics, such as click-through rates, but erode perceived credibility and trust in the source, with users reporting diminished article quality perceptions post-exposure.[89][90] Digital-native outlets exhibit higher clickbait propensity, driving a self-perpetuating cycle where engagement incentives prioritize virality over veracity, often sidelining substantive reporting.[91] Negativity bias in headlines exploits humans' evolved psychological preference for threat-related information, amplifying coverage of crises, scandals, and conflicts to sustain audience attention. Cross-national psychophysiological experiments demonstrate stronger arousal responses to negative news stimuli than positive equivalents, with skin conductance rising 15-20% more for adverse stories across diverse populations.[92] Longitudinal sentiment analysis of U.S. headlines from 47 outlets shows a steady decline in average positivity since 2000, with negative emotional terms like anger, fear, and disgust surging by factors of 2-5 times in major publications.[93] Causal field studies on viral news confirm negative and emotional wording boosts consumption by 10-30%, as platforms reward high-engagement content regardless of outlet ideology.[80] This bias persists even in alternative media, though mainstream sources, incentivized by scale, often amplify it systematically, fostering distorted threat perceptions that overshadow positive developments.[94][95] Critics argue these tactics distort public discourse by prioritizing outrage over evidence, with repeated exposure correlating to heightened anxiety and reduced social trust; for instance, negative headline scanning induces cognitive biases that diminish prosocial behaviors.[96] While engagement metrics validate short-term efficacy, long-term effects include audience fatigue and skepticism toward journalism, as evidenced by declining trust surveys linking sensational coverage to perceived institutional bias.[9] Empirical scrutiny underscores that, absent countervailing standards, economic pressures in ad-driven models perpetuate these distortions across ideological lines.[97]

Ideological Bias and Misrepresentation

A 2023 study analyzing 1.8 million headlines from U.S. news outlets between 2000 and 2020 found that coverage of domestic politics and social issues has grown increasingly polarized, with headlines from left-leaning sources showing more negative sentiment toward conservative topics and vice versa, indicating a measurable ideological slant that distorts neutral reporting.[6] This polarization arises from selective framing, where outlets emphasize facts aligning with their ideological priors while downplaying contradictory evidence, often prioritizing narrative coherence over comprehensive accuracy.[98] Mainstream media outlets, which empirical analyses consistently rate as left-leaning due to journalists' self-reported ideologies and citation patterns favoring liberal think tanks, frequently misrepresent conservative figures and policies through loaded language in headlines.[99] For instance, a UCLA study of news coverage revealed systematic bias in word choice and story selection, with outlets like The New York Times and CNN exhibiting favoritism toward Democratic viewpoints, such as framing economic policies under Republican administrations more critically than equivalent Democratic ones.[100] Such practices stem from institutional homogeneity in newsrooms, where over 90% of journalists identify as left-of-center, leading to causal distortions that attribute unrelated societal issues to conservative policies while understating similar outcomes under progressive governance.[101] Misrepresentation extends to social issues, where headlines often amplify unverified claims aligning with progressive narratives, as seen in coverage of events like the 2020 U.S. riots, where left-leaning outlets downplayed violence in headlines (e.g., emphasizing "protests" over property damage) compared to right-leaning sources.[102] This selective emphasis, documented in comparative content analyses, fosters public misperception by decoupling headlines from underlying data, such as crime statistics or policy outcomes, thereby reinforcing ideological echo chambers rather than informing causal understanding.[103] Critics, including media scholars, argue this bias erodes trust, with surveys showing conservative audiences perceiving systemic distortion due to these patterns, though outlets rarely correct headline-level framing post-publication.[104] While right-leaning outlets like Fox News exhibit analogous biases favoring conservative narratives, the prevalence in mainstream (e.g., ABC, NBC) amplifies misrepresentation's reach, as these dominate audience share and set agenda priorities.[105] Empirical models estimating bias via language processing confirm that headline sentiment correlates more with outlet ideology than event verifiability, underscoring how ideological priors causally drive omissions, such as ignoring fiscal impacts of left-leaning spending bills while highlighting conservative tax cuts' deficits.[106] Addressing this requires transparency in sourcing and algorithmic detection of slant, though self-regulation remains limited amid competitive pressures for engagement.[101]Inaccuracy, Ethical Lapses, and Legal Challenges

Headlines in journalism have frequently been sources of inaccuracy when they diverge from the factual content of the accompanying article, often to enhance click-through rates or visual appeal. This mismatch, prevalent in online media, can mislead readers into forming erroneous impressions before engaging with the full story; for instance, a 2016 study by the Media Insight Project found that up to 59% of headlines in major outlets overstated or simplified complex findings to attract attention. Such practices undermine the journalistic imperative for precision, as articulated in the Society of Professional Journalists (SPJ) Code of Ethics, which requires reporters to avoid "intentionally distorting information" and to ensure headlines accurately reflect reported truths.[107] Ethical lapses in headline composition commonly involve sensationalism or selective framing that prioritizes emotional provocation over balanced representation, contravening professional standards like those from the SPJ emphasizing "fairness" and "minimizing harm."[108] In digital eras, this manifests as clickbait—headlines promising exaggerated revelations, such as implying causation from correlation in scientific reporting—which erodes audience trust and contributes to widespread misinformation cascades. Historical precedents include yellow journalism tactics in the late 19th century, where publishers like William Randolph Hearst used inflammatory headlines to stoke public fervor, as during the Spanish-American War buildup. Modern codes, including those from the Radio Television Digital News Association, explicitly counsel against headlines that "sensationalize" events at the expense of context, viewing them as breaches of accountability to the public.[109] Legal challenges to headlines typically arise under defamation law when they convey false statements of fact that damage individuals' or entities' reputations. In the U.S., the Supreme Court's 1964 decision in New York Times Co. v. Sullivan set a high bar for public figures, requiring proof of "actual malice"—publication with knowledge of falsity or reckless disregard for verification—before media outlets face liability for libelous content, including headlines.[110] Courts treat headlines as integral to the publication, potentially actionable if they imply verifiable falsehoods rather than protected opinion; the 1990 Milkovich v. Lorain Journal Co. ruling clarified that no categorical "opinion privilege" shields implications of criminal or unethical conduct, applying to headline phrasing that suggests perjury or deceit.[111] Notable settlements underscore risks: Fox News agreed to pay Dominion Voting Systems $787 million in 2023 to resolve defamation claims over false 2020 election headlines and coverage alleging rigged voting machines, despite internal acknowledgments of inaccuracy.[112] Similarly, in 2025, Donald Trump filed a $15 billion suit against The New York Times, alleging defamatory reporting on his Epstein ties, with headlines amplifying disputed assertions.[113] These cases highlight how headlines, as the most visible element, amplify legal exposure when diverging from evidence-based reporting.Notable Examples

Historically Significant Headlines

Historically significant headlines have captured turning points in global affairs, often distilling complex events into stark declarations that informed and mobilized public sentiment. These front-page announcements, appearing in major newspapers, documented milestones such as the conclusions of wars, technological triumphs, and profound tragedies, frequently influencing immediate societal responses and long-term historical narratives. Their brevity amplified their reach, with print runs disseminating the news to millions amid limited communication alternatives.[114] The Armistice ending World War I exemplified such impact. On November 11, 1918, the New York Times proclaimed "ARMISTICE SIGNED—END OF THE WAR!" across its front page, announcing Germany's surrender after four years of conflict that resulted in approximately 20 million deaths. This headline, accompanied by reports of revolutionary upheaval in Berlin, signaled the collapse of empires and the onset of peace negotiations leading to the Treaty of Versailles.[114][115] The sinking of the RMS Titanic produced another landmark declaration. The New York Times reported on April 16, 1912, "TITANIC SINKS FOUR HOURS AFTER HITTING ICEBERG; 1,800 PROBABLY LOST," detailing the maritime disaster that claimed over 1,500 lives despite the ship's purported unsinkability. This coverage exposed flaws in early 20th-century transatlantic safety protocols and spurred international maritime reforms, including enhanced lifeboat requirements.[116] Erroneous yet enduring, the 1948 U.S. presidential election headline "DEWEY DEFEATS TRUMAN" in the Chicago Tribune on November 3 illustrated journalistic pitfalls under deadline pressures. Printed before final tallies confirmed Harry S. Truman's victory over Thomas E. Dewey by a 2.1 million vote margin, the blunder—stemming from premature projections—became symbolic of media overconfidence, famously captured in Truman's triumphant display of the paper.[114] The atomic bombings of Japan yielded headlines heralding a new era of warfare. On August 7, 1945, the New York Times stated "DAY OF ATOM BOMB DAWNS; FOE'S CITIES HIT," describing the Hiroshima strike that killed an estimated 70,000-80,000 instantly and contributed to Japan's surrender on August 15, averting further Allied invasions but igniting debates on nuclear ethics. Subsequent V-J Day coverage, such as "PEACE!" in various U.S. dailies, marked World War II's Pacific conclusion after 405,000 American and millions of global fatalities.[117][114] Neil Armstrong's moonwalk prompted triumphant announcements worldwide. The New York Times headlined "MEN WALK ON MOON" on July 21, 1969, chronicling Apollo 11's success—fulfilling President Kennedy's 1961 pledge amid the Cold War space race—and viewed by an estimated 650 million television audience, it underscored U.S. technological supremacy and inspired generations in STEM fields.[115] The September 11, 2001, attacks elicited unified shock. Outlets like the New York Post blared "U.S. ATTACKED" or "WAR ON AMERICA," reporting the hijackings that destroyed the World Trade Center towers, damaged the Pentagon, and killed 2,977 people, catalyzing the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq and reshaping global counterterrorism doctrines.[117][118]Modern Controversial or Influential Cases

In the 2014 Ferguson unrest following the police shooting of Michael Brown, numerous media outlets amplified eyewitness claims that Brown had his hands raised in surrender while shouting "Don't shoot," leading to headlines such as CNN's "Ferguson grand jury weighing whether to indict officer in Michael Brown shooting" that framed the incident as emblematic of systemic police aggression. The U.S. Department of Justice investigation, released in March 2015, concluded that Brown did not raise his hands in surrender and instead charged toward officer Darren Wilson after an initial altercation, contradicting the primary narrative promoted in early coverage.[119] This discrepancy fueled protests and the "Black Lives Matter" slogan but was later acknowledged as built on unreliable witness statements by outlets like the Washington Post. The 2014 Rolling Stone article "A Rape on Campus: A Fraternity's Silence Helped Shield Alleged Sexual Assaults," which detailed an alleged gang rape of a University of Virginia student named "Jackie" at a Phi Kappa Psi fraternity event, generated headlines across media implying institutional complicity in campus sexual violence. Investigations by the magazine itself and Columbia Journalism School revealed that Jackie's story contained fabrications, including nonexistent assailants and unverifiable events, prompting a full retraction on April 5, 2015, and a defamation lawsuit settlement against Rolling Stone for $1.65 million in 2020.[120][121] The case highlighted failures in journalistic verification, as the article bypassed standard fact-checking to prioritize a compelling narrative on fraternity culture.[122] During the 2019 March for Life in Washington, D.C., a viral video clip showed Covington Catholic High School student Nicholas Sandmann standing near Native American activist Nathan Phillips, prompting headlines like the Washington Post's "Students in MAGA hats mock Native American at Indigenous Peoples March" that portrayed the teens as instigators of racial provocation while wearing Trump apparel. Extended footage released subsequently revealed that Black Hebrew Israelites had initiated verbal confrontations toward the students and Phillips before the standoff, leading to apologies and retractions from CNN, the Washington Post, and NBC, which settled defamation suits with Sandmann totaling over $700,000 by 2020.[123][124] This incident exemplified rapid amplification of incomplete video evidence, contributing to doxxing and threats against the students before fuller context emerged.[125] In October 2020, the New York Post published "Smoke and Fire: Hunter Biden's Perfectly Legal but Morally Bankrupt Business Dealings," detailing emails from a laptop purportedly belonging to Hunter Biden suggesting influence peddling with Ukrainian and Chinese entities. Major outlets like NPR dismissed it with headlines such as "Hunter Biden Story Is Russian Disinfo, Dozens Of Former Intel Officials Say," citing a letter from 51 former intelligence officials labeling it potential Russian election interference, while Twitter blocked sharing and Facebook throttled visibility ahead of the presidential election. Forensic analyses by CBS News in 2022 and the FBI's possession of the laptop since 2019 confirmed the device's authenticity and contents, with no evidence of Russian fabrication emerging, though the story's pre-election suppression correlated with polls showing 17% of Biden voters might have reconsidered support if aware.[126]Societal Impact

Influence on Public Opinion and Perception

Headlines frequently serve as the primary or sole point of contact with news stories for large segments of the public, thereby molding initial impressions and enduring beliefs without necessitating full article engagement. A 2014 analysis of American media habits indicated that just 41 percent of respondents had consumed in-depth news coverage beyond headlines in the prior week, underscoring reliance on succinct summaries for opinion formation.[127] More recent data from a 2024 Penn State University study revealed that over 75 percent of social media users share news links without accessing the underlying content, allowing headline phrasing to dictate perceived narrative validity and dissemination.[128] This pattern persists across platforms, where superficial scanning amplifies the disproportionate sway of provocative or simplified wording over comprehensive reporting. ![Average yearly sentiment of headlines across 47 popular news media outlets.png][center] The linguistic structure of headlines, including framing and epistemic cues, systematically alters audience interpretations and attitudes toward reported events. A May 2024 study in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences experimentally showed that headlines employing certain versus uncertain language—such as "causes" versus "may cause"—elevate perceived factual certainty and reader endorsement, even when contradicted by article details, due to primacy effects in information processing.[129] Psychological research on framing effects corroborates this, demonstrating that equivalent facts presented through gain-oriented or loss-oriented headlines yield opposing public risk perceptions and policy preferences; for instance, emphasizing economic "gains" versus "losses" in coverage shifts support for interventions by up to 20 percentage points in controlled trials.[130] Such mechanisms enable headlines to prime selective recall and emotional responses, fostering polarized views aligned with the chosen emphasis rather than objective causality. Sensational or negatively toned headlines exacerbate perceptual distortions by prioritizing emotional arousal over nuance, driving heightened public apprehension and behavioral responses. Empirical analysis of millions of online interactions found that headlines incorporating negative terms increased consumption by approximately 2.3 times compared to neutral or positive equivalents, cultivating a feedback loop of amplified threat perception irrespective of event probability.[79] Repeated exposure to misleading headlines, particularly false ones, further entrenches inaccuracies; a 2018 experiment using real-world fake news instances established that mere prior viewing boosted subsequent accuracy ratings by 0.75 points on a 7-point scale, a phenomenon termed the "illusory truth effect," which compounds across low-credibility sources.[131] These dynamics contribute to societal overestimation of rare risks, such as episodic crimes or policy failures, while underemphasizing chronic issues lacking dramatic phrasing, as evidenced by longitudinal sentiment tracking in major outlets revealing persistent negativity trends since 2000.[79]Role in Political Discourse and Media Dynamics

Headlines serve as primary entry points into political narratives, exerting outsized influence on discourse by condensing complex events into emotionally charged or selectively framed summaries that guide public interpretation. Empirical analysis demonstrates that headlines operate as autonomous framing devices, shaping reader attitudes independently of article content; for instance, a 2025 study of news framing found headlines capable of priming biases and altering policy evaluations even among brief exposures.[132] This agenda-setting function extends to politics, where media outlets prioritize issues via headline prominence, often amplifying conflicts over substantive policy to align with audience predispositions or competitive incentives.[133] In media dynamics, the shift to digital platforms has intensified headline-driven competition for attention, fostering sensationalism and ideological slant as outlets vie for clicks amid declining ad revenues. Data from 1.8 million U.S. news stories between 2014 and 2020 show headlines on domestic politics and social issues growing more polarized, with sentiment diverging sharply along partisan lines—left-leaning outlets increasingly negative toward conservative topics and vice versa.[6] Negative phrasing in headlines boosts consumption rates by up to 2.3 times compared to neutral or positive equivalents, per a 2023 analysis of online news engagement, perpetuating a cycle where emotive content dominates feeds and reinforces selective exposure.[79] Mainstream outlets, often critiqued for systemic left-leaning biases in source selection and framing, contribute to this by disproportionately emphasizing scandals involving right-leaning figures while downplaying equivalents on the left, as evidenced by partisan trust gaps where only 11% of Republicans express confidence in media versus 70% of Democrats in 2024 Gallup polling.[134][135] These dynamics exacerbate political polarization by entrenching echo chambers, with headlines acting as gateways to tailored content ecosystems. Longitudinal studies link repeated exposure to partisan headlines—via social media algorithms or outlet preferences—to heightened affective polarization, where mere familiarity with slanted phrasing biases voter evaluations by 10-15% in experimental settings mimicking election coverage.[136] In U.S. elections, horse-race focused headlines, which comprised over 60% of 2020 campaign coverage in major outlets, prioritize viability over issues, distorting discourse and voter turnout patterns; for example, early negative framing of underdog candidates can suppress support by amplifying perceived inevitability of frontrunners.[137] Social media amplifies this, as headline virality on platforms like X or Facebook correlates with 20-30% greater slant in subsequent shares, further fragmenting consensus and eroding cross-partisan dialogue.[138] ![Average yearly sentiment of headlines across 47 popular news media outlets][center]This variation in headline sentiment underscores divergent media dynamics, with partisan outlets diverging more sharply over time to capture loyal audiences.[6]

References

- ./assets/Emotionality_in_news_articles_headlines_since_2000.png