Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Higenamine

View on WikipediaThis article needs more reliable medical references for verification or relies too heavily on primary sources. (December 2018) |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

1-[(4-Hydroxyphenyl)methyl]-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline-6,7-diol

| |

| Other names

norcoclaurine, demethylcoclaurine

| |

| Identifiers | |

| |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| KEGG | |

| MeSH | higenamine |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII |

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C16H17NO3 | |

| Molar mass | 271.316 g·mol−1 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Higenamine (norcoclaurine) is a chemical compound found in a variety of plants including Nandina domestica (fruit), Aconitum carmichaelii (root), Asarum heterotropioides, Galium divaricatum (stem and vine), Annona squamosa, and Nelumbo nucifera (lotus seeds).

Higenamine is found as an ingredient in sports and weight loss dietary supplements sold in the US.[1] The US Food and Drug Administration has received reports of adverse effects from higenamine-containing supplements since 2014, but higenamine's health risks remain poorly understood.[1]

Legality

[edit]Higenamine, also known as norcoclaurine HCl, is legal to use within food supplements in the UK, EU, the USA and Canada. Its main use is within food supplements developed for weight management and sports supplements.[1] Traditional formulations with higenamine have been used for thousands of years within Chinese medicine and come from a variety of sources including fruit and orchids. There are no studies comparing the safety of modern formulations (based on synthetic higenamine) with traditional formulations. Nevertheless, it will not be added to the EU 'novel foods' catalogue, which details all food supplements that require a safety assessment certificate before use.[2]

Along with many other β2 agonists, higenamine is prohibited by World Anti-Doping Agency for use in sports.[3] In 2016, French footballer Mamadou Sakho was temporarily banned by UEFA after testing positive for Higenamine causing the player to miss the 2016 Europa League final. The ban was lifted after the player successfully made the mitigating defence that there was an absence of significant negligence as the substance was not on the list of banned substances despite drugs of the same category – β2 agonists – being banned.[4][5][6][7]

Pharmacology

[edit]Since higenamine is present in plants which have a history of use in traditional medicine, the pharmacology of this compound has attracted scientific interest.

In animal models, higenamine has been demonstrated to be a β2 adrenoreceptor agonist.[8][9][10][11][12] Adrenergic receptors, or adrenoceptors, belong to the class of G protein–coupled receptors, and are the most prominent receptors in the adipose membrane, besides also being expressed in skeletal muscle tissue. These adipose membrane receptors are classified as either α or β adrenoceptors. Although these adrenoceptors share the same messenger, cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), the specific transduction pathway depends on the receptor type (α or β). Higenamine partly exerts its actions by the activation of an enzyme, adenylate cyclase, responsible for boosting the cellular concentrations of the adrenergic second messenger, cAMP.[13]

In a rodent model, it was found that higenamine produced cardiotonic, vascular relaxation, and bronchodilator effects.[14][15] In particular, higenamine, via a beta-adrenoceptor mechanism, induced relaxation in rat corpus cavernosum, leading to improved vasodilation and erectile function.

Related to improved vasodilatory signals, higenamine has been shown in animal models to possess antiplatelet and antithrombotic activity via a cAMP-dependent pathway, suggesting higenamine may contribute to enhanced vasodilation and arterial integrity.[8][13][15][16]

In humans, higenamine has been studied as an investigational drug in China for use as a pharmacological agent for cardiac stress tests as well as for treatment of a number of cardiac conditions including bradyarrhythmias.[1] The human trials were relatively small (ranging from 10 to 120 subjects) and higenamine was administered intravenously, most commonly using gradual infusions of 2.5 or 5 mg.[1] Higenamine consistently increased heart rate but had variable effects on blood pressure. One small study described higenamine's effect on cardiac output: higenamine led to an increased ejection fraction in 15 patients with heart disease.[1]

Toxicity

[edit]The safety of orally administered higenamine in humans is unknown. During a study of acute toxicity, mice were orally administered the compound at a dose of 2 g per kg of bodyweight. No mice died during the study.[17] In human trials of intravenous higenamine, subjects who received higenamine reported shortness of breath, racing heart, dizziness, headaches, chest tightness.[1]

Biosynthesis

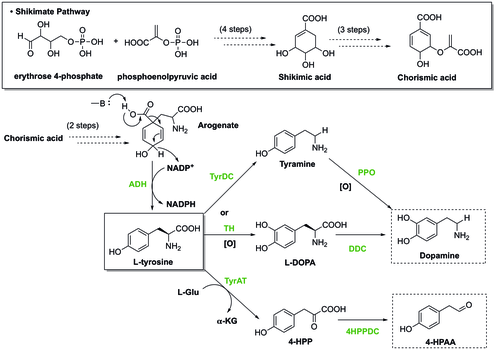

[edit](S)-Norcoclaurine/Higenamine is at the center of benzylisoquinoline alkaloid (BIA) biosynthesis. In spite of large structure diversity, BIAs biosynthesis all share a common first committed intermediate (S)-norcoclaurine.[18] (S)-norcoclaurine is produced by the condensation of two tyrosine derivatives, dopamine and 4-hydroxyphenylacetaldehyde (4-HPAA).

In plants, tyrosine is synthesized through Shikimate pathway, during which the last step involves decarboxylation and dehydrogenation of arogenate to give L-tyrosine. To generate dopamine from tyrosine, there are two pathways. In one pathway, tyrosine undergoes decarboxylation catalyzed by tyrosine decarboxylase (TyrDC) to become tyramine, which is then followed by oxidation of polyphenol oxidase (PPO) to render dopamine.[19][20] Alternatively, tyrosine can be oxidized by tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) to form L-DOPA, which is then later decarboxylated by DOPA decarboxylase (DDC) to provide dopamine. Besides that, the other starting material, 4-HPAA, is generated through a first transamination by tyrosine transeaminase (TyrAT) to form 4-hydroxylphenylpyruvate (4-HPP), and a subsequent decarboxylation by 4-HPP decarboxylase.[20]

The condensation of dopamine and 4-HPAA to form (S)-norcoclaurine is catalyzed by (S)-norcoclaurine synthase (NCS).[21] Such reaction is one type of Pictet-Spengler reaction. In this reaction, Asp-141 and Glu-110 in the NCS active site are involved in the activation of the amine and carbonyl respectively to facilitate imine formation. Then, the molecule will be cyclized as the mechanism shown below to produce (S)-nococlaurine.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Cohen, Pieter A.; Travis, John C.; Keizers, Peter H. J.; Boyer, Frederick E.; Venhuis, Bastiaan J. (6 September 2018). "The stimulant higenamine in weight loss and sports supplements". Clinical Toxicology. 57 (2): 125–130. doi:10.1080/15563650.2018.1497171. PMID 30188222. S2CID 52165506.

- ^ "Novel food catalogue". Food Safety. European Commission.

- ^ "Prohibited Substances at All Times". List of Prohibited Substances and Methods. World Anti-Doping Agency. 1 January 2016. Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- ^ "Mamadou Sakho: Liverpool defender investigated over failed drugs test". BBC. 23 April 2016.

- ^ "Euro 2016: Mamadou Sakho could play for France as Uefa opts not to extend ban". BBC. 28 May 2016.

- ^ "Mamadou Sakho - UEFA decision raises key questions". Echo. 28 May 2016.

- ^ "Mamadou Sakho still set to miss EURO 2016, despite being cleared of doping". Get French Football. 29 May 2016.

- ^ a b Tsukiyama M, Ueki T, Yasuda Y, Kikuchi H, Akaishi T, Okumura H, Abe K (October 2009). "Beta2-adrenoceptor-mediated tracheal relaxation induced by higenamine from Nandina domestica Thunberg". Planta Medica. 75 (13): 1393–9. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1185743. PMID 19468973. S2CID 260280804.

- ^ Kashiwada Y, Aoshima A, Ikeshiro Y, Chen YP, Furukawa H, Itoigawa M, Fujioka T, Mihashi K, Cosentino LM, Morris-Natschke SL, Lee KH (January 2005). "Anti-HIV benzylisoquinoline alkaloids and flavonoids from the leaves of Nelumbo nucifera, and structure-activity correlations with related alkaloids". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 13 (2): 443–8. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2004.10.020. PMID 15598565.

- ^ Kimura I, Chui LH, Fujitani K, Kikuchi T, Kimura M (May 1989). "Inotropic effects of (+/-)-higenamine and its chemically related components, (+)-R-coclaurine and (+)-S-reticuline, contained in the traditional sino-Japanese medicines "bushi" and "shin-i" in isolated guinea pig papillary muscle". Japanese Journal of Pharmacology. 50 (1): 75–8. doi:10.1254/jjp.50.75. PMID 2724702.

- ^ Kang YJ, Lee YS, Lee GW, Lee DH, Ryu JC, Yun-Choi HS, Chang KC (October 1999). "Inhibition of activation of nuclear factor kappaB is responsible for inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase expression by higenamine, an active component of aconite root". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 291 (1): 314–20. doi:10.1016/S0022-3565(24)35103-1. PMID 10490919.

- ^ Yun-Choi HS, Pyo MK, Park KM, Chang KC, Lee DH (October 2001). "Anti-thrombotic effects of higenamine". Planta Medica. 67 (7): 619–22. doi:10.1055/s-2001-17361. PMID 11582538. S2CID 260279615.

- ^ a b Kam SC, Do JM, Choi JH, Jeon BT, Roh GS, Chang KC, Hyun JS (2012). "The relaxation effect and mechanism of action of higenamine in the rat corpus cavernosum". International Journal of Impotence Research. 24 (2): 77–83. doi:10.1038/ijir.2011.48. PMID 21956762.

- ^ Bai G, Yang Y, Shi Q, Liu Z, Zhang Q, Zhu YY (October 2008). "Identification of higenamine in Radix Aconiti Lateralis Preparata as a beta2-adrenergic receptor agonist1". Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 29 (10): 1187–94. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7254.2008.00859.x. PMID 18817623.

- ^ a b Pyo MK, Lee DH, Kim DH, Lee JH, Moon JC, Chang KC, Yun-Choi HS (July 2008). "Enantioselective synthesis of (R)-(+)- and (S)-(-)-higenamine and their analogues with effects on platelet aggregation and experimental animal model of disseminated intravascular coagulation". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 18 (14): 4110–4. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.05.094. PMID 18556200.

- ^ Liu W, Sato Y, Hosoda Y, Hirasawa K, Hanai H (November 2000). "Effects of higenamine on regulation of ion transport in guinea pig distal colon". Japanese Journal of Pharmacology. 84 (3): 244–51. doi:10.1254/jjp.84.244. PMID 11138724.

- ^ Lo CF, Chen CM (February 1997). "Acute toxicity of higenamine in mice". Planta Medica. 63 (1): 95–6. doi:10.1055/s-2006-957619. PMID 9063102. S2CID 260281301.

- ^ Hagel JM, Facchini PJ (May 2013). "Benzylisoquinoline alkaloid metabolism: a century of discovery and a brave new world". Plant & Cell Physiology. 54 (5): 647–72. doi:10.1093/pcp/pct020. PMID 23385146.

- ^ Soares AR, Marchiosi R, Siqueira-Soares RC, Barbosa de Lima R, Marchiosi R, Dantas dos Santos W, Ferrarese-Filho O (March 2014). "The role of L-DOPA in plants". Plant Signaling & Behavior. 9 (4) e28275. Bibcode:2014PlSiB...9E8275S. doi:10.4161/psb.28275. PMC 4091518. PMID 24598311.

- ^ a b Beaudoin GA, Facchini PJ (July 2014). "Benzylisoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis in opium poppy". Planta. 240 (1): 19–32. Bibcode:2014Plant.240...19B. doi:10.1007/s00425-014-2056-8. PMID 24671624.

- ^ Lichman BR, Sula A, Pesnot T, Hailes HC, Ward JM, Keep NH (October 2017). "Structural Evidence for the Dopamine-First Mechanism of Norcoclaurine Synthase". Biochemistry. 56 (40): 5274–5277. doi:10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00769. PMC 5637010. PMID 28915025.

Higenamine

View on GrokipediaHigenamine, also known as norcoclaurine, is a naturally occurring alkaloid and non-selective beta-2 adrenergic receptor agonist found in various plants, including Aconitum carmichaelii, Nandina domestica, Asarum heterotropoides, and Tinospora crispa.[1][2] It exhibits pharmacological effects such as bronchodilation, improved cellular energy metabolism, anti-oxidative stress, and anti-apoptotic activity, which have led to its investigation for potential therapeutic applications in conditions like asthma, heart failure, and inflammatory pain.[3][4][5] Higenamine has been incorporated into dietary supplements marketed for weight loss, athletic performance enhancement, and cardiovascular support, though clinical evidence for efficacy remains limited.[6] Since 2017, it has been prohibited at all times by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) under the beta-2 agonists category due to its stimulant properties and risk of unintentional doping from plant-derived sources.[7][8] This ban has sparked concerns over contamination in herbal products and foodstuffs, highlighting challenges in distinguishing exogenous intake from endogenous or dietary origins.[1][9]

Chemical Properties and Occurrence

Molecular Structure and Synthesis

Higenamine, also known as norcoclaurine, is a tetrahydroisoquinoline alkaloid with the molecular formula C₁₆H₁₇NO₃ and a molar mass of 271.316 g/mol.[10] Its IUPAC name is 1-[(4-hydroxyphenyl)methyl]-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline-6,7-diol.[10] The molecule consists of a 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline core bearing hydroxyl groups at the 6- and 7-positions of the benzene ring and a 4-hydroxybenzyl substituent at the 1-position, conferring phenolic functionalities that contribute to its adrenergic activity.[10] Higenamine exists as a pair of enantiomers, with the naturally occurring form being the (S)-enantiomer.[11] Chemical synthesis of higenamine typically employs the Pictet-Spengler reaction, involving condensation of a protected dopamine derivative with a 4-hydroxyphenylacetic acid derivative, followed by cyclization and deprotection.[12] One established method starts from 4-methoxyphenylacetic acid and β-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)ethylamine, proceeding through amide formation, reduction to the amine, and acid-catalyzed cyclization to form the tetrahydroisoquinoline ring, with subsequent demethylation to yield the trihydroxy compound.[12] Industrial production favors chemical synthesis over extraction due to efficiency, often yielding the hydrochloride salt for pharmaceutical applications.[13] Alternative routes include multi-step processes using oxalyl chloride for activation and subsequent reductions, achieving higenamine hydrochloride in several steps.[14]Biosynthesis Pathway

Higenamine, or (S)-norcoclaurine, is synthesized in plants as the initial intermediate in the benzylisoquinoline alkaloid (BIA) pathway via the stereoselective Pictet-Spengler condensation of dopamine and 4-hydroxyphenylacetaldehyde (4-HPAA), catalyzed by norcoclaurine synthase (NCS).[15][16] Both substrates originate from L-tyrosine: dopamine forms through sequential hydroxylation to L-DOPA and decarboxylation, while 4-HPAA arises from transamination to 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate followed by decarboxylation.[17] This condensation represents the first committed step in BIA biosynthesis, which proceeds to diverse alkaloids such as morphine in species like opium poppy (Papaver somniferum).[15] NCS, a member of the pathogenesis-related protein 10 (PR10)/Bet v1 family, facilitates the reaction through imine formation between 4-HPAA and dopamine, yielding an iminium ion intermediate that undergoes enantioselective cyclization to produce (S)-norcoclaurine with high stereospecificity.[15] The enzyme, purified from cell cultures of meadow rue (Thalictrum flavum), exhibits a native molecular mass of approximately 28 kDa, optimal pH of 6.5–7.0, and follows an ordered bi-uni mechanism where 4-HPAA binds first, displaying cooperative kinetics toward dopamine.[16] Expression of NCS is highest in roots, suggesting tissue-specific regulation of pathway flux.[16] Subsequent modifications of (S)-norcoclaurine, including 6-O-methylation to (S)-coclaurine and further N- and O-methylations, lead to reticuline, a central hub for BIA diversification, underscoring higenamine's foundational role.[15] NCS homologs have been identified across BIA-producing plants, including Japanese goldthread (Coptis japonica), highlighting evolutionary conservation of this biosynthetic entry point.[15]Natural Plant Sources

Higenamine, also known as (R)-norcoclaurine, occurs naturally in various plants, primarily as a benzylisoquinoline alkaloid, with concentrations varying by plant part and species.[1] It has been detected in species used in traditional Asian herbal medicines, serving as a potential source for unintentional doping or dietary exposure.[18] Key sources include members of the Nelumbonaceae, Ranunculaceae, and Berberidaceae families, where higenamine levels can reach pharmacologically relevant amounts in certain tissues.[19] Nelumbo nucifera (lotus) is among the richest sources, with higenamine identified in leaves (up to 9,667.6 μg/kg in dried samples), seeds (1,183.8 μg/kg), and particularly high concentrations in the plumule, exceeding levels in other plants.[1] [19] This aquatic plant's extracts have been analyzed for β2-agonist content, confirming higenamine's presence through LC-MS methods.[20] Other documented plants include Nandina domestica (heavenly bamboo), where higenamine is a constituent alkaloid, and Aconitum carmichaelii and Aconitum japonicum (monkshood species), traditional sources in Chinese medicine.[21] [22] Tinospora crispa (a vine used in Southeast Asian remedies) and Asarum heterotropioides and Asarum sieboldii (wild gingers) also contain detectable higenamine.[18] [23] Gnetum parvifolium and Galium species (bedstraws) have been reported as additional reservoirs.[18] [21]| Plant Species | Notable Parts Analyzed | Key Findings on Higenamine |

|---|---|---|

| Nelumbo nucifera | Leaves, seeds, plumule | Highest concentrations; up to ~9,667 μg/kg in dried leaves[1] |

| Nandina domestica | Whole plant extracts | Constituent alkaloid; variable levels[21] |

| Aconitum carmichaelii | Roots/tubers | Present in herbal extracts[22] |

| Tinospora crispa | Stems/leaves | Detected via analytical methods[20] |

Historical Context

Traditional Medicinal Uses

Higenamine, also known as norcoclaurine, occurs naturally in several plants utilized in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), particularly species of Aconitum such as Aconitum carmichaelii (known as Fuzi or Radix Aconiti lateralis praeparata), where it contributes to cardiotonic properties.[2] In TCM formulations, Fuzi has been employed for centuries to address cardiac conditions including heart failure, coronary artery disease, bradycardia, and arrhythmias, with higenamine identified as a key bioactive alkaloid mediating these effects through its presence in the herb.[24] Preparations combining Fuzi with ginger have traditionally managed symptoms of heart failure by promoting yang energy restoration and alleviating cold-induced cardiac weakness, aligning with TCM principles of balancing vital energies.[2] Additional sources of higenamine in TCM include Aconitum japonicum, valued for its role in enhancing cardiac function and treating circulatory disorders, as documented in classical texts and modern phytochemical analyses confirming its alkaloid content.[25] While higenamine's isolation and direct administration are modern developments, traditional uses focused on whole-plant decoctions or processed roots to mitigate toxicity risks inherent to raw Aconitum, which contains other cardioactive diterpenoids alongside higenamine.[26] These applications extended to supportive roles in managing syncope, collapse, and painful joints in broader Asian ethnopharmacological contexts, though cardiac indications predominate in verified TCM records.[13] Empirical evidence from historical TCM practice, corroborated by subsequent pharmacological studies, underscores higenamine's contribution to inotropic and chronotropic effects observed in these herbal remedies, without reliance on isolated compound testing in antiquity.[27]Discovery and Early Research

Higenamine, chemically known as (RS)-norcoclaurine, was first isolated in 1976 from the roots of Aconitum japonicum, a species of the Ranunculaceae family used in traditional East Asian medicine.[28] Japanese researchers Takashi Kosuge and colleagues extracted it as a cardiotonic alkaloid from ethanolic plant preparations, identifying its benzylisoquinoline structure through spectroscopic analysis.[1] This discovery built on observations of heart-stimulating effects in Aconitum extracts, attributing them partly to higenamine's presence alongside other alkaloids like coryneine.[29] Early research in the late 1970s focused on confirming higenamine's isolation from additional Aconitum species, such as Aconitum carmichaelii, and elucidating its stereochemistry as a racemic mixture or enantiopure (S)-form depending on the plant source.[1] Studies from Japan and China, where Aconitum roots (known as Fuzi) held historical therapeutic significance for cardiac conditions, demonstrated higenamine's positive inotropic and chronotropic effects in isolated heart preparations, mimicking beta-adrenergic stimulation without initial molecular receptor details.[29] These investigations, often tied to validating traditional uses, reported dose-dependent increases in myocardial contractility at concentrations around 10^{-6} to 10^{-5} M in animal models.[30] By the early 1980s, higenamine was detected in other plant genera, including lianas and Annona species, expanding its known natural distribution beyond Ranunculaceae.[1] Preliminary pharmacological assays linked it to enhanced acetylcholine release via beta-receptor activation, laying groundwork for later cardiovascular applications, though human trials remained absent until the 2010s.[31] These findings, primarily from peer-reviewed journals in Asia, emphasized empirical extraction and bioassay data over synthetic analogs, reflecting resource constraints in early alkaloid research.[32]Pharmacology

Mechanism of Action

Higenamine primarily functions as a selective agonist at β₂-adrenergic receptors, with additional evidence supporting dual agonism at β₁-adrenergic receptors.[33][27] This binding activates G-protein-coupled receptor signaling, specifically the stimulatory Gₛ protein, which in turn activates adenylyl cyclase to convert ATP into cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP).[34][33] Elevated intracellular cAMP levels activate protein kinase A (PKA), which phosphorylates target proteins to elicit downstream effects, including relaxation of smooth muscle in bronchial and vascular tissues, increased glucose uptake in skeletal muscle, and enhanced cardiac contractility via positive inotropy.[33][35] In vitro assays in Chinese hamster ovary cells expressing human β₂-receptors have quantified higenamine's potency for cAMP accumulation at a pEC₅₀ of 6.6 (equivalent to 230 nM), establishing it as a full agonist approximately 10-fold less potent than salbutamol but comparable in efficacy to epinephrine.[33] These receptor-mediated effects explain higenamine's bronchodilatory, vasodilatory, and cardiostimulatory properties, as demonstrated in isolated tissue preparations where relaxation of precontracted tracheal, colonic, and corpus cavernosum smooth muscle was blocked by β-antagonists like propranolol.[35][33] While additional pathways such as PI3K/Akt modulation have been implicated in broader cellular responses like anti-apoptosis, the core mechanism remains adrenergic receptor agonism.[36]Physiological and Therapeutic Effects

Higenamine functions primarily as a non-selective β-adrenergic receptor agonist, activating both β1- and β2-receptors to elicit sympathomimetic effects.[31] Physiologically, it increases heart rate by stimulating sinoatrial node cells without inducing arrhythmias in isolated perfused guinea pig hearts at concentrations up to 10 μM.[37] It also enhances cardiac contractility and output via β1-receptor activation, while β2-receptor agonism promotes bronchodilation and vasodilation, potentially improving airflow and peripheral blood flow.[31] In metabolic contexts, acute oral doses (e.g., 1.5–3 mg in supplements) elevate circulating free fatty acids and energy expenditure in humans, suggesting lipolytic activity through β2-mediated cAMP signaling.[38] Additionally, it augments acetylcholine release and muscle tension in neuromuscular preparations, countering inhibitory effects of other alkaloids like coryneine.[39] In vascular physiology, higenamine exhibits antispasmodic properties against cold-induced vasoconstriction in rat mesenteric arteries, modulating PI3K/Akt, ROS/α2C-adrenergic receptor, and PTK9 pathways independently of AMPK/eNOS, at doses of 1–30 μM.[40] It inhibits platelet aggregation and demonstrates anti-inflammatory actions by suppressing matrix metalloproteinase expression in models of fine-dust-induced lung injury.[41] Preclinical studies indicate cardioprotective effects, such as reducing ischemia/reperfusion injury and myocyte apoptosis through β2-AR/PI3K/AKT pathway activation in rat models.[42] In skin physiology, it boosts collagen production via TGF-β/Smad3 signaling and mitigates UVB-induced aging markers in human dermal fibroblasts.[43] Therapeutically, higenamine shows promise in cardiovascular applications, including chronic heart failure management via dual β1/β2 agonism to enhance contractility without excessive tachycardia, as evidenced in traditional Chinese medicine extracts and animal models.[27] It protects against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity by preserving myocardial energy metabolism when combined with [44]-gingerol in rodent studies.[45] Anti-inflammatory and antioxidative properties may benefit conditions like disseminated intravascular coagulation and shock, though human data remain limited to observational supplement use.[46] In respiratory therapy, β2-agonism supports bronchodilation for asthma relief, as seen in aconite-derived preparations.[2] Emerging evidence suggests antidepressant effects by restoring astrocytic gap junctions and reducing neuroinflammation in mouse models of chronic stress, at doses of 20 mg/kg.[47] Overall, while preclinical models demonstrate broad benefits including anti-apoptosis and improved cellular energy, clinical trials are scarce, with effects inferred largely from in vitro and animal data.[3]Modern Applications and Claims

Use in Dietary Supplements

Higenamine is incorporated into various dietary supplements primarily as a stimulant for purported benefits in weight loss, fat metabolism, and exercise performance. It functions as a beta-2 adrenergic agonist, mimicking effects similar to ephedrine, and is marketed in pre-workout formulas, energy boosters, and thermogenic products to enhance lipolysis, increase metabolic rate, and improve endurance.[48][49] In products analyzed from the U.S. market, higenamine dosages have been detected ranging up to 62 mg per serving, often without explicit labeling or in combination with other stimulants like caffeine.[48] Manufacturers include it based on its natural occurrence in plants such as Nelumbo nucifera (lotus seed) and claims of bronchodilatory and cardiovascular effects, though these are extrapolated from limited pharmacological data rather than robust supplement-specific trials.[7][50] Despite promotional claims, higenamine's presence in supplements raises concerns due to inconsistent disclosure and potential for contamination, with some products containing undeclared amounts that could exceed safe thresholds.[51] The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has received adverse event reports linked to higenamine-containing supplements since 2014, highlighting risks from unverified formulations.[24]Evidence on Efficacy for Weight Loss and Performance

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial involving 12 recreational female basketball players (aged 29–41 years) examined the effects of 75 mg daily higenamine supplementation (divided into three 25 mg doses) over 21 days on exercise performance and weight loss. Participants underwent assessments of cardiopulmonary fitness (VO₂max), anthropometric measures, resting metabolic rate, and serum free fatty acids. No significant improvements were observed in VO₂max, body weight, body fat percentage, or exercise performance metrics compared to placebo (p > 0.05 for all primary outcomes). The study concluded that this regimen does not enhance cardiopulmonary fitness or promote weight loss in this population, though it was deemed safe with no adverse events reported.[50] An acute crossover study in 16 healthy adults evaluated a higenamine-containing dietary supplement (dosage not specified as isolated higenamine but part of a formula) on lipolytic markers post-ingestion. Free fatty acid levels increased significantly at 60, 120, and 180 minutes compared to placebo, suggesting potential short-term stimulation of lipolysis via β₂-adrenoceptor agonism, but no changes occurred in glycerol levels or respiratory exchange ratio, limiting inferences on sustained fat oxidation or energy expenditure. This provides mechanistic support for possible fat mobilization but does not demonstrate weight loss efficacy or performance benefits over time.[52] Preclinical data indicate higenamine activates β₂-adrenoceptors, potentially mimicking effects of other agonists like clenbuterol in promoting bronchodilation and lipolysis, which theoretically could aid endurance or fat loss; however, human trials extrapolating these to performance enhancement are absent or negative. Narrative reviews highlight the scarcity of robust clinical evidence, with no long-term randomized trials confirming benefits for obesity or athletic output, and emphasize that WADA's prohibition stems from structural similarity to prohibited stimulants rather than proven ergogenic effects. Overall, available human data do not support claims of efficacy for weight loss or performance enhancement.[24][53]Legality and Regulation

Prohibition in Sports by WADA

Higenamine was incorporated into the World Anti-Doping Agency's (WADA) Prohibited List effective January 1, 2017, under the S3 category of beta-2 agonists.[54][1] This classification applies to non-specified beta-2 agonists, which WADA prohibits due to their capacity to stimulate adrenergic receptors, potentially enhancing athletic performance through mechanisms such as bronchodilation, increased lipolysis, and elevated heart rate and contractility.[8][1] The substance is banned at all times, both in-competition and out-of-competition, without any permitted threshold concentration in urine or other biological samples, distinguishing it from specified beta-2 agonists like salbutamol that allow limited therapeutic use under strict conditions.[8][55] WADA's rationale aligns with its three criteria for prohibition: higenamine meets the threshold for potential performance enhancement, poses health risks including cardiovascular strain and irregular heart rhythms, and contravenes the spirit of sport by providing unfair advantages not achievable through training alone.[8][56] Prior to 2017, higenamine evaded explicit listing despite its presence in some dietary supplements marketed for fat loss and energy, but growing evidence of its beta-adrenergic activity prompted WADA's monitoring program to elevate it to full prohibition.[22][57] The 2017 addition reflected consultations with experts on its pharmacological profile, similar to other sympathomimetics like clenbuterol, which are also S3 substances.[49] As of the 2025 Prohibited List, higenamine remains explicitly named and banned, with no exemptions for natural occurrence in plants or foods.[54][58]Status in Dietary Supplements and Pharmaceuticals

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has determined that higenamine hydrochloride is not generally recognized as safe (GRAS) for use in dietary supplements and does not qualify as a dietary ingredient under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, leading to multiple warning letters issued to manufacturers for marketing adulterated products containing it.[59][60] In May 2022, the FDA explicitly listed higenamine HCl (also known as norcoclaurine HCl or demethylcoclaurine HCl) in its Dietary Supplement Ingredient Advisory List, citing its lack of prior approval as a food additive or color additive and absence of notification as a new dietary ingredient.[61] Additionally, FDA Import Alert 54-18, effective since March 2021, mandates detention without physical examination of dietary supplements imported with higenamine, reflecting regulatory enforcement against its unapproved presence.[62] Despite these restrictions, higenamine has appeared in pre-workout and weight-loss supplements, often unlabeled or with inconsistent dosing, prompting concerns from public health researchers about inaccurate labeling and potential contamination risks.[51][57] In the European Union and United Kingdom, higenamine remains legal for inclusion in food supplements as of the latest available regulatory assessments, though its use is monitored due to its beta-2 agonist properties and presence in traditional herbal contexts.[63] In contrast, Australia classifies higenamine without a history of safe use as a food and prohibits it as a novel food ingredient under Food Standards Australia New Zealand guidelines, resulting in import restrictions and seizures of non-compliant products.[64] Canada permits its sale in supplements, similar to the EU, but athletes face risks from its prohibition under anti-doping rules.[65] Regarding pharmaceuticals, higenamine has never received approval from the FDA or equivalent agencies in major jurisdictions for any therapeutic indication, lacking clinical evaluation as a new drug despite its historical role in traditional Chinese herbal medicine.[22][23] No peer-reviewed evidence or regulatory filings indicate pharmaceutical authorization elsewhere, positioning it outside standard drug development pathways and limiting its application to unregulated or traditional formulations.[25]Safety Profile

Human Clinical Studies

A phase I clinical trial conducted in 2012 evaluated the pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and safety of intravenous higenamine in 10 healthy Chinese adults (4 males, 6 females), administering escalating doses of 0.5 to 4.0 μg/kg/min over 3 minutes (total dose up to approximately 22.5 μg/kg).[66] The compound exhibited rapid distribution with a short elimination half-life of about 8 minutes, alongside dose-dependent increases in heart rate but no significant changes in blood pressure.[66] Higenamine was well tolerated, with only two transient adverse events reported: mild elevation in bilirubin in one subject and moderate dizziness/nausea in another, resolving without intervention.[66] An 8-week double-blind, randomized controlled trial in 2015 assessed oral higenamine safety in 48 healthy young men (ages 23–26 years), who received 100–150 mg daily, either alone or combined with caffeine and yohimbe bark extract.[67] No significant alterations occurred in vital signs (heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate), complete blood counts, metabolic panels, liver enzymes, lipids, or urinalysis across baseline, week 4, and week 8 assessments.[67] Adverse events were minimal and transient, including a rash in the caffeine group and temporary symptoms from accidental double-dosing in one higenamine group, with no discontinuations required, indicating good short-term tolerability at supplement-relevant doses.[67] A 2021 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial examined 75 mg daily oral higenamine (25 mg three times daily) over 21 days in 12 recreational female basketball players (ages 29–41 years), primarily for exercise performance but including safety monitoring.[50] No serious adverse effects emerged, with transient headaches (3/6 in higenamine group vs. 2/6 placebo) and one case of dry mouth reported, alongside stable blood pressure, heart rate, hematology, clinical chemistry (including urea, creatinine, lipids, and enzymes), and no discontinuations.[50] These findings align with prior data on tolerability but highlight the need for larger, longer-term studies, as existing trials involve small cohorts and limited durations, precluding conclusions on chronic use or vulnerable populations.[31]Reported Toxicity and Risks

Reported adverse effects of higenamine primarily involve cardiovascular symptoms, consistent with its action as a beta-adrenergic agonist, including increased blood pressure, irregular heartbeats, heart palpitations, and chest pain.[1][22] Other commonly noted side effects from human exposure include dizziness, nausea, headaches, dry mouth, and transient chest congestion.[1][22] In intravenous administration studies at doses of 22.5 µg/kg, participants experienced minor, short-term effects such as dizziness, heart palpitations, dry mouth, and chest congestion.[1] Oral intake from dietary supplements averaging 62 mg per serving has been linked to elevated blood pressure and irregular heart rhythms in some reports.[1] A single case report documented paraspinal muscle rhabdomyolysis in a 22-year-old male following consumption of a higenamine-containing supplement, though the exact dose was undisclosed.[1][49] Controlled human trials indicate limited toxicity at moderate oral doses. An 8-week study in 48 healthy young men using up to 150 mg/day higenamine (alone or combined with caffeine and yohimbe) reported no significant alterations in heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, blood chemistry, liver enzymes, or lipid profiles, with only isolated minor incidents like a rash attributed to other components.[67] Similarly, a 21-day randomized trial in recreational female athletes at 75 mg/day found no changes in vital signs, blood markers (e.g., CK, AST, ALT, lipids), or complete blood counts, though transient headaches and dry mouth occurred in a subset of participants.[49] Risks are amplified by inconsistent dosing in unregulated supplements, where actual higenamine content often deviates substantially from labels (0.01% to 200% of stated amounts), potentially leading to unintended high exposures and heightened cardiovascular strain.[22] FDA adverse event reports have included cardiac-related complaints such as palpitations and altered heart rates, underscoring concerns over cardiotoxicity, particularly in combination with other stimulants.[68] Overall, while acute human toxicity appears low based on available data, long-term safety remains understudied, with potential for exacerbated effects in vulnerable populations or via interactions enhancing tachyarrhythmia.[1]Controversies

Doping Incidents and Unintentional Exposure

Higenamine detections in anti-doping tests have increased since its prohibition by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) in 2017 as a β₂-agonist banned at all times, with the substance ranking second among reported β₂-agonists in WADA laboratories by 2020.[1][7] Most positive findings stem from dietary supplements promoted for fat loss or energy enhancement, where higenamine is often undeclared or mislabeled, resulting in athletes' claims of unintentional exposure.[7][69] The WADA minimum required performance level for higenamine in urine is 10 ng/mL, above which an adverse analytical finding is reported.[70][71] Notable doping incidents include the 2020 two-year suspension of English footballer Bambo Diaby for higenamine presence linked to weight-loss products.[72] Similarly, MMA fighter Jake Collier was sanctioned by the United States Anti-Doping Agency (USADA) following a positive test for the substance.[73] In athletics, Kenyan runner Abraham Kiptoo Kangogo faced an adverse finding in 2019, confirmed in a 2020 Athletics Integrity Unit decision, though no intent was disputed.[74] Serbian swimmer Jovan Lekić tested positive twice in June and July 2021 during FINA competitions, attributing the results to contaminated supplements; his four-year ban was reduced to two years upon appeal citing no-fault ingestion.[75] Unintentional exposure via natural sources appears low-risk under typical conditions. Higenamine occurs endogenously in plants like Nelumbo nucifera (lotus) and Annona species, but urinary levels from consuming beetroot products or Annona fruits rarely surpass 1% of the 10 ng/mL threshold.[58][76] However, concentrated lotus plumule extracts in herbal preparations can elevate urine concentrations above the limit, posing a potential hazard for athletes using traditional medicines.[55] Studies on plant-derived higenamine emphasize that while dietary supplements drive most violations, vigilance against herbal contaminants is warranted due to variable extraction yields and bioavailability.[1][18]Issues with Supplement Contamination

Dietary supplements, particularly those marketed for weight loss, energy enhancement, or derived from herbal extracts, have been found to contain higenamine at varying and often undeclared levels, contributing to risks of unintentional doping and inconsistent dosing. A 2018 peer-reviewed analysis of 24 supplements sold in the United States confirmed higenamine presence ranging from trace quantities to 62 ± 6.0 mg per serving, with many products inaccurately labeled or failing to disclose specific dosages, leading to unpredictable intake that could exceed anti-doping thresholds.[77] Such discrepancies arise from inadequate quality control in manufacturing, including cross-contamination during production or variability in raw material sourcing.[21] Higenamine contamination also stems from its natural occurrence in certain plant-based ingredients commonly used in supplements, such as lotus seed embryos (Nelumbo nucifera) and beetroot (Beta vulgaris), where extraction processes can concentrate the compound beyond label expectations or without declaration. For instance, testing of commercial lotus seed embryo supplements revealed higenamine concentrations sufficient to produce urinary levels potentially triggering adverse analytical findings under World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) criteria after short-term consumption, even when not explicitly listed on labels.[55] Similarly, higenamine was detected in the majority of beetroot-containing foodstuffs and supplements analyzed, with experimental evidence indicating de novo synthesis or accumulation during plant processing, underscoring how herbal formulations can inadvertently harbor prohibited substances.[58] These contamination issues have been linked to anti-doping rule violations, as dietary supplements account for a significant portion of unintentional positives; one review estimated that up to 28% of tested supplements contain undeclared doping agents, including beta-2 agonists like higenamine, amplifying health and regulatory risks for consumers and athletes.[78] Peer-reviewed evaluations emphasize that while intentional adulteration occurs, inadvertent contamination from botanical sources or supply chain lapses is prevalent, with recommendations for third-party testing to mitigate exposure.[19] Despite WADA's establishment of a minimum reporting level for higenamine in 2020 (10 ng/mL in urine), pre-existing cases highlight ongoing challenges in supplement purity, as variability persists across global markets.[79]References

- Nov 30, 2017 · Higenamine main use is related to weight loss and it could be found (un)labeled in different dietary supplements. The objective of this study ...