Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

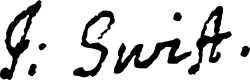

Jonathan Swift

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2025) |

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667 – 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish[1] writer, essayist, satirist, and Anglican cleric. In 1713, he became the dean of St Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin,[2] and was given the sobriquet "Dean Swift". His trademark deadpan and ironic style of writing, particularly in works such as A Modest Proposal (1729), has led to such satire being subsequently termed as "Swiftian".[3] He wrote the satirical book Gulliver's Travels (1726), which became his best-known publication and popularised the fictional island of Lilliput. Following the remarkable success of his works, Swift came to be regarded by many as the greatest satirist of the Georgian era and is considered one of the foremost prose satirists in the history of English literature.[4][5][6]

Key Information

Swift also authored works such as A Tale of a Tub (1704) and An Argument Against Abolishing Christianity (1712). He originally published all of his works under pseudonyms—including Lemuel Gulliver, Isaac Bickerstaff, M. B. Drapier—or anonymously. He was a master of two styles of satire, the Horatian and Juvenalian styles. During the early part of his career, he travelled extensively in Ireland and Great Britain, and these trips helped develop his understanding of human nature and social conditions, which he would later depict in his satirical works. Swift was also very active in clerical circles, due to his affiliations to St Patrick's Cathedral in Dublin. He had supported the Glorious Revolution and joined the Whigs party early on. Swift was related to many prominent figures of his time, including John Temple, John Dryden, William Davenant, and Francis Godwin.

In 1700, Swift moved to Trim, County Meath, and many of his major works were written during this time. His writings reflected much of his political experiences of the previous decade, especially those with the British government under the Tories. Swift used several pseudonyms to publish his early works, with Isaac Bickerstaff being the most recognisable one. Scholars of his works have also suggested that these pseudonyms might have protected Swift from persecution in the politically sensitive conditions of England and Ireland under which he wrote many of his popular satires.

Since the late 18th century, Swift has emerged as the most popular Irish author globally, and his novel Gulliver's Travels, which is considered one of the most famous classics of English literature, has retained its position as the most printed book by an Irish writer in libraries and bookstores worldwide. He continues to be held in high regard in Ireland with many streets, monuments, festivals, and regional attractions named after him. Swift has also influenced several notable authors with his works over the following centuries, including John Ruskin and George Orwell.

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]Jonathan Swift was born on 30 November 1667 in Dublin in the Kingdom of Ireland. He was the second child and only son of Jonathan Swift (1640–1667) and his wife Abigail Erick (or Herrick) of Frisby on the Wreake in Leicestershire.[7] His father was a native of Goodrich, Herefordshire, but he accompanied his brothers to Ireland to seek their fortunes in law after their royalist father's estate was brought to ruin during the English Civil War. His maternal grandfather, James Ericke, was the vicar of Thornton in Leicestershire. In 1634 the vicar was convicted of Puritan practices. Sometime thereafter, Ericke and his family, including his young daughter Abigail, fled to Ireland.[8]

Swift's father joined his elder brother, Godwin, in the practice of law in Ireland.[9] He died in Dublin about seven months before his namesake was born.[10][11] He died of syphilis, which he said he got from dirty sheets when out of town.[12]

His mother returned to England after his birth, leaving him in the care of his uncle Godwin Swift (1628–1695), a close friend and confidant of Sir John Temple, whose son later employed Swift as his secretary.[13]

At the age of one, child Jonathan was taken by his wet nurse to her hometown of Whitehaven, Cumberland, England. He said that there he learned to read the Bible. His nurse returned him to his mother, still in Ireland, when he was three.[14]

Swift's family had several interesting literary connections. His grandmother Elizabeth (Dryden) Swift was the niece of Sir Erasmus Dryden, grandfather of poet John Dryden. The same grandmother's aunt Katherine (Throckmorton) Dryden was a first cousin of Elizabeth, wife of Sir Walter Raleigh. His great-great-grandmother Margaret (Godwin) Swift was the sister of Francis Godwin, author of The Man in the Moone which influenced parts of Swift's Gulliver's Travels. His uncle Thomas Swift married a daughter of poet and playwright Sir William Davenant, a godson of William Shakespeare.[citation needed]

Swift's benefactor and uncle Godwin Swift took primary responsibility for the young man, sending him with one of his cousins to Kilkenny College (also attended by philosopher George Berkeley).[13] He arrived there at the age of six, where he was expected to have already learned the basic declensions in Latin. He had not and thus began his schooling in a lower form. Swift graduated in 1682, when he was 15.[15]

He attended Trinity College Dublin in 1682,[17] financed by Godwin's son Willoughby. The four-year course followed a curriculum largely set in the Middle Ages for the priesthood. The lectures were dominated by Aristotelian logic and philosophy. The basic skill taught to students was debate, and they were expected to be able to argue both sides of any argument or topic. Swift was an above-average student but not exceptional, and received his B.A. in 1686 "by special grace".[18]

Adult life

[edit]Swift was studying for his master's degree when political troubles in Ireland surrounding the Glorious Revolution forced him to leave for England in 1688, where his mother helped him get a position as secretary and personal assistant of Sir William Temple at Moor Park, Farnham.[19] Temple was an English diplomat who had arranged the Triple Alliance of 1668. He had retired from public service to his country estate, to tend his gardens and write his memoirs. Gaining his employer's confidence, Swift "was often trusted with matters of great importance."[20] Within three years of their acquaintance, Temple introduced his secretary to William III and sent him to London to urge the King to consent to a bill for triennial Parliaments.[citation needed]

Swift took up his residence at Moor Park where he met Esther Johnson, then eight years old, the daughter of an impoverished widow who acted as companion to Temple's sister Lady Giffard. Swift was her tutor and mentor, giving her the nickname "Stella", and the two maintained a close but ambiguous relationship for the rest of Esther's life.[21]

In 1690, Swift left Temple for Ireland because of his health, but returned to Moor Park the following year. The illness consisted of fits of vertigo or giddiness, now believed to be Ménière's disease, and it continued to plague him throughout his life.[22] During this second stay with Temple, Swift received his M.A. from Hart Hall, Oxford, in 1692. He then left Moor Park, apparently despairing of gaining a better position through Temple's patronage, in order to become an ordained priest in the Established Church of Ireland. He was appointed to the prebend of Kilroot in the Diocese of Connor in 1694,[23] with his parish located at Kilroot, near Carrickfergus in County Antrim.[citation needed]

Swift appears to have been miserable in his new position, being isolated in a small, remote community far from the centres of power and influence. While at Kilroot, however, he may well have become romantically involved with Jane Waring, whom he called "Varina", the sister of an old college friend.[20] A letter from him survives, offering to remain if she would marry him and promising to leave and never return to Ireland if she refused. She presumably refused, because Swift left his post and returned to England and Temple's service at Moor Park in 1696, and he remained there until Temple's death. There he was employed in helping to prepare Temple's memoirs and correspondence for publication. During this time, Swift wrote The Battle of the Books, a satire responding to critics of Temple's Essay upon Ancient and Modern Learning (1690), though Battle was not published until 1704.[citation needed]

Temple died on 27 January 1699.[20] Swift, normally a harsh judge of human nature, said that all that was good and amiable in mankind had died with Temple.[20] He stayed on briefly in England to complete editing Temple's memoirs, and perhaps in the hope that recognition of his work might earn him a suitable position in England. His eventual publication of the third volume of Temple's memoirs, in 1709,[24] made enemies among some of Temple's family and friends, in particular Temple's formidable sister Martha, Lady Giffard, who objected to indiscretions included in the memoirs.[21] Moreover, she noted that Swift had borrowed from her own biography, an accusation that Swift denied.[25] Swift's next move was to approach King William directly, based on his imagined connection through Temple and a belief that he had been promised a position. This failed so miserably that he accepted the lesser post of secretary and chaplain to the Earl of Berkeley, one of the Lords Justice of Ireland. However, when he reached Ireland, he found that the secretaryship had already been given to another, though he soon obtained the living of Laracor, Agher, and Rathbeggan, and the prebend of Dunlavin[26] in St Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin.[27]

Swift ministered to a congregation of about 15 at Laracor, which was just over four and a half miles (7.2 km) from Summerhill, County Meath, and twenty miles (32 km) from Dublin. He had abundant leisure for cultivating his garden, making a canal after the Dutch fashion of Moor Park, planting willows, and rebuilding the vicarage. As chaplain to Lord Berkeley, he spent much of his time in Dublin and travelled to London frequently over the next ten years. In 1701, he anonymously published the political pamphlet A Discourse on the Contests and Dissentions in Athens and Rome.[citation needed]

Writer

[edit]Swift resided in Trim, County Meath after 1700. He wrote many of his works during this period. In February 1702, Swift received his Doctor of Divinity degree from Trinity College Dublin. That spring he travelled to England and then returned to Ireland in October, accompanied by Esther Johnson—now 20—and his friend Rebecca Dingley, another member of William Temple's household. There is a great mystery and controversy over Swift's relationship with Esther Johnson, nicknamed "Stella". Many, notably his close friend Thomas Sheridan, believed that they were secretly married in 1716; others, like Swift's housekeeper Mrs Brent and Rebecca Dingley, who lived with Stella all through her years in Ireland, dismissed the story as absurd.[28] Yet Swift certainly did not wish her to marry anyone else: in 1704, when their mutual friend William Tisdall informed Swift that he intended to propose to Stella, Swift wrote to him to dissuade him from the idea. Although the tone of the letter was courteous, Swift privately expressed his disgust for Tisdall as an "interloper", and they were estranged for many years. In 1713, Swift was appointed as Dean of St Patrick's Cathdral, Dublin, a position he held until his death.[citation needed]

During his visits to England in these years, Swift published A Tale of a Tub and The Battle of the Books (1704) and began to gain a reputation as a writer. This led to close, lifelong friendships with Alexander Pope, John Gay, and John Arbuthnot, forming the core of the Martinus Scriblerus Club (founded in 1713).[citation needed]

Swift became increasingly active politically in these years.[29] Swift had supported the Glorious Revolution and early in his life belonged to the Whigs.[30][31] As a member of the Anglican Church, he feared a return of the Catholic monarchy and "Papist" absolutism.[31] From 1707 to 1709 and again in 1710, Swift was in London unsuccessfully urging upon the Whig administration of Lord Godolphin the claims of the Irish clergy to the First-Fruits and Twentieths ("Queen Anne's Bounty"), which brought in about £2,500 a year, already granted to their brethren in England. He found the opposition Tory leadership more sympathetic to his cause, and when they came to power in 1710, he was recruited to support their cause as editor of The Examiner. In 1711, Swift published the political pamphlet The Conduct of the Allies, attacking the Whig government for its inability to end the prolonged war with France. The incoming Tory government conducted secret (and illegal) negotiations with France, resulting in the Treaty of Utrecht (1713) ending the War of the Spanish Succession.[citation needed]

Swift was part of the inner circle of the Tory government,[32] and often acted as mediator between Henry St John (Viscount Bolingbroke), the secretary of state for foreign affairs (1710–15), and Robert Harley (Earl of Oxford), lord treasurer and prime minister (1711–14). Swift recorded his experiences and thoughts during this difficult time in a long series of letters to Esther Johnson, collected and published after his death as A Journal to Stella. The animosity between the two Tory leaders eventually led to the dismissal of Harley in 1714. With the death of Queen Anne and the accession of George I that year, the Whigs returned to power, and the Tory leaders were tried for treason for conducting secret negotiations with France.[citation needed]

Swift has been described by scholars[who?] as "a Whig in politics and Tory in religion" and Swift related his own views in similar terms, stating that as "a lover of liberty, I found myself to be what they called a Whig in politics ... But, as to religion, I confessed myself to be an High-Churchman."[30] In his Thoughts on Religion, fearing the intense partisan strife waged over religious belief in seventeenth-century England, Swift wrote that "Every man, as a member of the commonwealth, ought to be content with the possession of his own opinion in private."[30] However, it should be borne in mind that, during Swift's time period, terms like "Whig" and "Tory" both encompassed a wide array of opinions and factions, and neither term aligns with a modern political party or modern political alignments.[30]

Also during these years in London, Swift became acquainted with the Vanhomrigh family, Dutch merchants who had settled in Ireland, then moved to London, and "became involved with" one of the daughters, Esther. Swift furnished Esther with the nickname "Vanessa"—derived by adding "Essa", a pet form of Esther, to the "Van" of her surname, Vanhomrigh—and she features as one of the main characters in his poem Cadenus and Vanessa. This poem and their correspondence suggest that Esther was infatuated with Swift and that he may have reciprocated her affections, only to regret this and then try to break off the relationship.[33] Esther followed Swift to Ireland in 1714 and settled at her old family home, Celbridge Abbey. Their uneasy relationship continued for some years; then there appears to have been a confrontation, possibly involving Esther Johnson. Esther Vanhomrigh died in 1723 at the age of 35, after having destroyed the will she had made in Swift's favour.[34] Another lady with whom he had a close but less intense relationship was Anne Long, a "toast" of the Kit-Cat Club.[citation needed]

Final years

[edit]

Before the fall of the Tory government, Swift had hoped that his services would be rewarded with a church appointment in England. However, Queen Anne appeared to have taken a dislike to Swift and thwarted these efforts. Her dislike has been attributed to A Tale of a Tub, which she thought blasphemous, compounded by The Windsor Prophecy, where Swift, with a surprising lack of tact, advised the Queen on which of her bedchamber ladies she should and should not trust.[35] The best position his friends could secure for him was the Deanery of St Patrick's;[36] while this appointment was not in the Queen's gift, Anne, who could be a bitter enemy, made it clear that Swift would not have received the preferment if she could have prevented it.[37] With the return of the Whigs, Swift's best move was to leave England, and he returned to Ireland in disappointment, a virtual exile, to live "like a rat in a hole".[38]

Once in Ireland, however, Swift began to turn his pamphleteering skills in support of Irish causes, producing some of his most memorable works: Proposal for Universal Use of Irish Manufacture (1720), Drapier's Letters (1724), and A Modest Proposal (1729), earned him the status of an Irish patriot.[39] This new role was unwelcome to the Government, which made clumsy attempts to silence him. His printer, Edward Waters, was convicted of seditious libel in 1720, but four years later a grand jury refused to find that the Drapier's Letters, which though written under a pseudonym were universally known to be Swift's work, were seditious.[40] Swift responded with an attack on the Irish judiciary almost unparalleled in its ferocity, his principal target being the "vile and profligate villain" William Whitshed, Lord Chief Justice of Ireland.[41]

Also during these years, he began writing his masterpiece, Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World, in Four Parts, by Lemuel Gulliver, first a surgeon, and then a captain of several ships, better known as Gulliver's Travels. Much of the material reflects his political experiences of the preceding decade. For instance, the episode in which the giant Gulliver puts out the Lilliputian palace fire by urinating on it can be seen as a metaphor for the Tories' illegal peace treaty, a treaty he regarded as a good thing accomplished in an unfortunate manner. In 1726 he paid a long-deferred visit to London,[42] taking with him the manuscript of Gulliver's Travels. During his visit, he stayed with his old friends Alexander Pope, John Arbuthnot and John Gay, who helped him arrange for the anonymous publication of his book in November 1726 It was an immediate hit, with a total of three printings that year and another in early 1727. French, German, and Dutch translations appeared in 1727, and pirated copies were printed in Ireland.[citation needed]

In 1727, Swift returned to England one more time and stayed once again with Alexander Pope. The visit was cut short when Swift, receiving word that Esther Johnson was dying, rushed back home to be with her.[42] On 28 January 1728, Johnson died; Swift had prayed at her bedside, even composing prayers for her comfort. Swift could not bear to be present at the end, but on the night of her death he began to write his The Death of Mrs Johnson. He was too ill to attend the funeral at St Patrick's.[42] Many years later, a lock of hair, assumed to be Johnson's, was found in his desk, wrapped in a paper bearing the words, "Only a woman's hair."[citation needed]

Death

[edit]

Death became a persistent preoccupation in Swift's mind from this point. In 1731 he wrote Verses on the Death of Dr. Swift, his own obituary, published in 1739. In 1732, his good friend and collaborator John Gay had died. In 1735, John Arbuthnot, another friend from his days in London, also died, and in 1738 Swift too began to show signs of illness, perhaps even suffering a stroke in 1742, losing the ability to speak and realising his worst fears of becoming mentally disabled. ("I shall be like that tree", he once said. "I shall die at the top.")[43] He became increasingly quarrelsome, and long-standing friendships, like that with Thomas Sheridan, ended without sufficient cause. To protect him from unscrupulous hangers-on, who had begun to prey on the great man, his closest companions had him declared of "unsound mind and memory." However, it was long believed by many that Swift was actually insane at this point. In his book Literature and Western Man, author J. B. Priestley even cites the final chapters of Gulliver's Travels as proof of Swift's approaching "insanity". Bewley attributes his decline to 'terminal dementia'.[22]

In part VIII of his series, The Story of Civilization, Will Durant describes the final years of Swift's life as exhibiting:

Definite symptoms of madness ... [first appearing] in 1738. In 1741, guardians were appointed to take care of his affairs and watch lest in his outbursts of violence, he should do himself harm. In 1742, he suffered great pain from the inflammation of his left eye, which swelled to the size of ... [a chicken's] egg; five attendants had to restrain him from tearing out his eye. He went a whole year without uttering a word.[44]

In 1744, Alexander Pope died. Then on 19 October 1745, Swift died, at nearly 78.[45] After being laid out in public view for the people of Dublin to pay their last respects, he was buried in his own cathedral by Esther Johnson's side, in accordance with his wishes. The bulk of his fortune (£12,000) was left to found a hospital for the mentally ill, originally known as St Patrick's Hospital for Imbeciles, which opened in 1757, and which still exists as a psychiatric hospital.[45]

- (Text extracted from the introduction to The Journal to Stella by George A. Aitken and from other sources).

Jonathan Swift wrote his own epitaph:

Hic depositum est Corpus |

Here is laid the Body |

W. B. Yeats poetically translated it from the Latin as:

- Swift has sailed into his rest;

- Savage indignation there

- Cannot lacerate his breast.

- Imitate him if you dare,

- World-besotted traveller; he

- Served human liberty.

His library is known through sale catalogues.[46]

Swift, Stella and Vanessa – an alternative view

[edit]British politician Michael Foot was a great admirer of Swift and wrote about him extensively. In Debts of Honour[47] he cites with approbation an explanation propounded by Denis Johnston of Swift's behaviour towards Stella and Vanessa.

Pointing to contradictions in the received information about Swift's origins and parentage, Johnston postulates that Swift's real father was Sir William Temple's father, Sir John Temple, who was Master of the Rolls in Dublin at the time. It is widely thought that Stella was Sir William Temple's illegitimate daughter. So, if these speculations are to be credited, Swift was Sir William's brother and Stella's uncle. Marriage or close relations between Swift and Stella would therefore have been incestuous, an unthinkable prospect.[citation needed]

It follows that Swift could not have married Vanessa without Stella appearing to be a cast-off mistress, which appearance he would not contemplate leaving. Johnston's theory is expounded fully in his book In Search of Swift.[48] He is also cited in the Dictionary of Irish Biography[49] and the theory is presented without attribution in the Concise Cambridge History of English Literature.[50]

Works

[edit]Swift was a prolific writer. The collection of his prose works (Herbert Davis, ed. Basil Blackwell, 1965–) comprises fourteen volumes. A 1983 edition of his complete poetry (Pat Rodges, ed. Penguin, 1983) is 953 pages long. One edition of his correspondence (David Woolley, ed. P. Lang, 1999) fills three volumes.

Major prose works

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2017) |

Swift's first major prose/satire work, A Tale of a Tub (1704, 1710),[51] demonstrates many of the themes and stylistic techniques he would employ in his later work. It is at once wildly playful and funny while being pointed and harshly critical of its targets.[citation needed] In its main thread, the Tale recounts the exploits of three sons, representing the main threads of Christianity, who receive a bequest from their father of a coat each, with the added instructions to make no alterations whatsoever. However, the sons soon find that their coats have fallen out of current fashion, and begin to look for loopholes in their father's will that will let them make the needed alterations. As each finds his own means of getting around their father's admonition, they struggle with each other for power and dominance. Inserted into this story, in alternating chapters, the narrator includes a series of whimsical "digressions" on various subjects.

In 1690, Sir William Temple, Swift's patron, published An Essay upon Ancient and Modern Learning a defence of classical writing (see Quarrel of the Ancients and the Moderns), holding up the Epistles of Phalaris as an example. William Wotton responded to Temple with Reflections upon Ancient and Modern Learning (1694), showing that the Epistles were a later forgery. A response by the supporters of the Ancients was then made by Charles Boyle (later the 4th Earl of Orrery and father of Swift's first biographer). A further retort on the Modern side came from Richard Bentley, one of the pre-eminent scholars of the day, in his essay Dissertation upon the Epistles of Phalaris (1699). The final words on the topic belong to Swift in his Battle of the Books (1697, published 1704) in which he makes a humorous defence on behalf of Temple and the cause of the Ancients.[citation needed]

In 1708, a cobbler named John Partridge published a popular almanac of astrological predictions. Because Partridge falsely determined the deaths of several church officials, Swift attacked Partridge in Predictions for the Ensuing Year by Isaac Bickerstaff, a parody predicting that Partridge would die on 29 March. Swift followed up with a pamphlet issued on 30 March claiming that Partridge had in fact died, which was widely believed despite Partridge's statements to the contrary. According to other sources,[52] Richard Steele used the persona of Isaac Bickerstaff, and was the one who wrote about the "death" of John Partridge and published it in The Spectator, not Jonathan Swift.

The Drapier's Letters (1724) was a series of pamphlets against the monopoly granted by the English government to William Wood to mint copper coinage for Ireland. It was widely believed that Wood would need to flood Ireland with debased coinage in order to make a profit. In these "letters", Swift posed as a shopkeeper or draper to criticise the plan. Swift's writing was so effective in undermining opinion in the project that a reward was offered by the government to anyone disclosing the true identity of the author. Though hardly a secret (on returning to Dublin after one of his trips to England, Swift was greeted with a banner, "Welcome Home, Drapier") no one turned Swift in, although there was an unsuccessful attempt to prosecute the publisher John Harding.[53] General outcry against the coinage caused Wood's patent to be rescinded in September 1725, and the coins were kept out of circulation.[54] In "Verses on the Death of Dr. Swift" (1739) Swift recalled this as one of his best achievements.

Gulliver's Travels, a large portion of which Swift wrote at Woodbrook House in County Laois, was published in 1726 and is regarded as his masterpiece. As with his other writings, the Travels was pseudonymously published under the name of the fictional eponymous character Lemuel Gulliver, who is described in the book's long title as a ship's surgeon and later a sea captain. Some of the correspondence between printer Benjamin Motte and Gulliver's also-fictional cousin negotiating the book's publication has survived. A satire of human nature based on Swift's experience of his times, Gulliver's Travels has often been mistakenly thought of (and published in bowdlerised form) as a children's book, and it has been criticised for its apparent misanthropy. Each of the four books—recounting four voyages to mostly fictional exotic lands—has a different theme. Critics hail the work as a satiric reflection on the shortcomings of Enlightenment thought.[citation needed]

In 1729, Swift's A Modest Proposal for Preventing the Children of Poor People in Ireland Being a Burden on Their Parents or Country, and for Making Them Beneficial to the Publick was published in Dublin by Sarah Harding.[55] It is a satire in which the narrator, with intentionally grotesque arguments, recommends that Ireland's poor escape their poverty by selling their children as food to the rich: "I have been assured by a very knowing American of my acquaintance in London, that a young healthy child well nursed is at a year old a most delicious nourishing and wholesome food ..." Following the satirical form, he introduces the reforms he is actually suggesting by deriding them:

Therefore let no man talk to me of other expedients ... taxing our absentees ... using [nothing] except what is of our own growth and manufacture ... rejecting ... foreign luxury ... introducing a vein of parsimony, prudence and temperance ... learning to love our country ... quitting our animosities and factions ... teaching landlords to have at least one degree of mercy towards their tenants. ... Therefore I repeat, let no man talk to me of these and the like expedients, till he hath at least some glympse of hope, that there will ever be some hearty and sincere attempt to put them into practice.[56]

Essays, tracts, pamphlets, periodicals

[edit]- "A Meditation upon a Broom-stick" (1703–10)

- "A Tritical Essay upon the Faculties of the Mind" (1707–11)[57]

- The Bickerstaff-Partridge Papers (1708–09)

- "An Argument Against Abolishing Christianity" (1708–11): Full text

- The Intelligencer (with Thomas Sheridan (1719–1788)): Text: Project Gutenberg Archived 30 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- The Examiner (1710): Texts: Project Gutenberg Archived 30 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- "A Proposal for Correcting, Improving and Ascertaining the English Tongue" (1712)

- "On the Conduct of the Allies" (1711)

- "Hints Toward an Essay on Conversation" (1713): Full text: Bartleby.com Archived 22 December 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- "The Publick Spirit of the Whigs, set forth in their generous encouragement of the author of the crisis" (1714)

- "A Letter to a Young Gentleman, Lately Entered into Holy Orders" (1720)

- "A Letter of Advice to a Young Poet" (1721): Full text: Bartleby.com Archived 5 December 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- Drapier's Letters (1724, 1725): Full text: Project Gutenberg Archived 30 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- "Bon Mots de Stella" (1726): a curiously irrelevant appendix to "Gulliver's Travels"

- "A Modest Proposal", perhaps the most notable satire in English, suggesting that the Irish should engage in cannibalism. (Written in 1729)

- "An Essay on the Fates of Clergymen"

- "A Treatise on Good Manners and Good Breeding": Full text: Bartleby.com

- "A modest address to the wicked authors of the present age. Particularly the authors of Christianity not founded on argument, and of The resurrection of Jesus considered" (1743–45?)

Poems

[edit]

- "Ode to the Athenian Society", Swift's first publication, printed in The Athenian Mercury in the supplement of Feb 14, 1691. Archived 13 May 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- Poems of Jonathan Swift, D.D. Texts at Project Gutenberg: Volume One, Volume Two Archived 7 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- "Baucis and Philemon" (1706–09): Full text: Munseys

- "A Description of the Morning" (1709): Full annotated text: U of Toronto; Another text: U of Virginia

- "A Description of a City Shower" (1710): Full text: Poetry Foundation

- "Cadenus and Vanessa" (1713): Full text: Munseys

- "Phillis, or, the Progress of Love" (1719): Full text: theotherpages.org Archived 25 October 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- Stella's birthday poems:

- 1719. Full annotated text: U of Toronto

- 1720. Full text

- 1727. Full text: U of Toronto

- "The Progress of Beauty" (1719–20): Full text: OurCivilisation.com

- "The Progress of Poetry" (1720): Full text: theotherpages.org Archived 25 October 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- "A Satirical Elegy on the Death of a Late Famous General" (1722): Full text: U of Toronto

- "To Quilca, a Country House not in Good Repair" (1725): Full text: U of Toronto

- "Advice to the Grub Street Verse-writers" (1726): Full text: U of Toronto

- "The Furniture of a Woman's Mind" (1727)

- "On a Very Old Glass" (1728): Full text: Gosford.co.uk

- "A Pastoral Dialogue" (1729): Full text: Gosford.co.uk

- "The Grand Question debated Whether Hamilton's Bawn should be turned into a Barrack or a Malt House" (1729): Full text: Gosford.co.uk

- "On Stephen Duck, the Thresher and Favourite Poet" (1730): Full text: U of Toronto

- "Death and Daphne" (1730): Full text: OurCivilisation.com

- "The Place of the Damn'd" (1731): Full text at the Wayback Machine (archived 27 October 2009)

- "A Beautiful Young Nymph Going to Bed" (1731): Full annotated text: Jack Lynch; Another text: U of Virginia

- "Strephon and Chloe" (1731): Full annotated text: Jack Lynch; Another text: U of Virginia Archived 30 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- "Helter Skelter" (1731): Full text: OurCivilisation.com

- "Cassinus and Peter: A Tragical Elegy" (1731): Full annotated text: Jack Lynch

- "The Day of Judgment" (1731): Full text

- "Verses on the Death of Dr. Swift, D.S.P.D." (1731–32): Full annotated texts: Jack Lynch, U of Toronto; Non-annotated text:: U of Virginia

- "An Epistle to a Lady" (1732): Full text: OurCivilisation.com

- "The Beasts' Confession to the Priest" (1732): Full annotated text: U of Toronto

- "The Lady's Dressing Room" (1732): Full annotated text: Jack Lynch

- "On Poetry: A Rhapsody" (1733)[58]

- "The Puppet Show"

- "The Logicians Refuted"

Correspondence, personal writings

[edit]- "When I Come to Be Old" – Swift's resolutions. (1699)

- A Journal to Stella (1710–13): Full text (presented as daily entries): The Journal to Stella; Extracts: OurCivilisation.com;

- Letters:

- Selected Letters

- To Oxford and Pope: OurCivilisation.com

- The Correspondence of Jonathan Swift, D.D. Edited by David Woolley. In four volumes, plus index volume. Frankfurt am Main; New York : P. Lang, c. 1999 – c. 2007.

Sermons, prayers

[edit]- Three Sermons and Three Prayers. Full text: U of Adelaide, Project Gutenberg Archived 24 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- Three Sermons: I. on mutual subjection. II. on conscience. III. on the Trinity. Text: Project Gutenberg

- Writings on Religion and the Church. Text at Project Gutenberg: Volume One Archived 30 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Volume Two Archived 30 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- "The First He Wrote Oct. 17, 1727." Full text: Worldwideschool.org Archived 18 February 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- "The Second Prayer Was Written Nov. 6, 1727." Full text: Worldwideschool.org Archived 18 February 2006 at the Wayback Machine

Miscellany

[edit]- Directions to Servants (1731): Full text: Jonathon Swift Archive

- A Complete Collection of Genteel and Ingenious Conversation (1738)

- "Thoughts on Various Subjects." Full text: U of Adelaide Archived 14 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Historical Writings: Project Gutenberg Archived 30 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- Swift quotes at Bartleby: Bartleby.com Archived 26 October 2005 at the Wayback Machine – 59 quotations, with notes

- The Benefit of Farting Explained, published under the pseudonym Don Fartinando Puff-Indorst, Professor of Bumbast in the University of Crackow.[59]

Legacy

[edit]Literary

[edit]

Since his death, Swift came to be regarded by many as the greatest satirist of the Georgian era,[4] and among the foremost writers of satire in the English language.[5] John Ruskin named him as one of the three people in history who were the most influential for him.[60] George Orwell named him as one of the writers he most admired, despite disagreeing with him on almost every moral and political issue.[61] Modernist poet Edith Sitwell wrote a fictional biography of Swift, titled I Live Under a Black Sun and published in 1937.[62] A. L. Rowse wrote a biography of Swift,[63] essays on his works,[64][65] and edited the Pan Books edition of Gulliver's Travels.[66]

Literary scholar Frank Stier Goodwin wrote a full biography of Swift: Jonathan Swift – Giant in Chains, issued by Liveright Publishing Corporation, New York (1940, 450pp, with Bibliography).

In 1982, Soviet playwright Grigory Gorin wrote a theatrical fantasy called The House That Swift Built based on the last years of Jonathan Swift's life and episodes of his works.[67] The play was filmed by director Mark Zakharov in the 1984 two-part television movie of the same name. Jake Arnott features him in his 2017 novel The Fatal Tree.[68] A 2017 analysis of library holdings data revealed that Swift is the most popular Irish author, and that Gulliver's Travels is the most widely held work of Irish literature in libraries globally.[69]

The first woman to write a biography of Swift was Sophie Shilleto Smith, who published Dean Swift in 1910.[70][71]

Eponymous places

[edit]Swift crater, a crater on Mars's moon Deimos, is named after Jonathan Swift, who predicted the existence of the moons of Mars.[72]

In honour of Swift's long-term residence in Trim, there are several monuments, statues and streets in the town. Most notable is Swift's Street, named after him. Trim also held a recurring festival in honour of Swift, called the Trim Swift Festival. In 2020, the festival was cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and has not been held since.[73]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Jonathan Swift at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ "Swift", Online literature, archived from the original on 3 August 2019, retrieved 17 December 2011

- ^ "What higher accolade can a reviewer pay to a contemporary satirist than to call his or her work Swiftian Archived 23 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine?" Frank Boyle, "Johnathan Swift", Ch 11 in A Companion to Satire: Ancient and Modern (2008), edited by Ruben Quintero, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 0470657952.

- ^ a b Hone, Joseph; Rogers, Pat (May 2024). Literature in Context: Jonathan Swift in Context. UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–10. ISBN 9781108831437.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ a b Hudson, Nicholas; Santesso, Aaron (October 2008). Swift's Travels: Eighteenth-Century Satire and its Legacy - Swift and his Antecedents. UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–12. ISBN 9780521879552.

- ^ "Jonathan Swift: Poetry Foundation". Chicago, Illinois. 2018.

- ^ Stephen, Leslie (1898). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 55. pp. 204–227.

- ^ Stubbs, John (2016). Jonathan Swift: The Reluctant Rebel. New York: WW Norton & Co. pp. 25–26.

- ^ Stubbs (2016), p. 43.

- ^ Degategno, Paul J.; Jay Stubblefield, R. (2014). Jonathan Swift. Infobase. ISBN 978-1438108513. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ "Jonathan Swift: His Life and His World". The Barnes & Noble Review. Archived from the original on 2 July 2014. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- ^ Stubbs (2016), p. 54.

- ^ a b Stephen DNB, p. 205.

- ^ Stubbs (2016), pp. 58–63.

- ^ Stubbs (2016), pp. 73–74.

- ^ Hourican, Bridget (2002). "Thomas Pooley". Royal Irish Academy – Dictionary of Irish Biography. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 3 November 2020.

- ^ Alumni Dublinenses Supplement, p. 116: a register of the students, graduates, professors and provosts of Trinity College in the University of Dublin (1593–1860), Burtchaell, G.D/Sadlier, T.U: Dublin, Alex Thom and Co., 1935.

- ^ Stubbs (2016), pp. 86–90.

- ^ Stephen DNB, p. 206.

- ^ a b c d Stephen DNB, p. 207.

- ^ a b Stephen DNB, p. 208.

- ^ a b Bewley, Thomas H., "The Health of Jonathan Swift," Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 1998;91:602–605.

- ^ "Fasti Ecclesiae Hibernicae: The succession of the prelates Volume 3" Cotton, H. p. 266: Dublin, Hodges & Smith, 1848–1878.

- ^ John Middleton Murry, Jonathan Swift. A Critical Biography, Noonday Press, 1955, pp. 154-158

- ^ Matthew, H. C. G.; Harrison, B., eds. (23 September 2004). "The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. ref:odnb/55435. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/55435. Retrieved 19 January 2023. (Subscription, Wikipedia Library access or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "Fasti Ecclesiae Hibernicae: The succession of the prelates Volume 2" Cotton, H. p. 165: Dublin, Hodges & Smith, 1848–1878.

- ^ Stephen DNB, p. 209.

- ^ Stephen DNB, pp. 215–217.

- ^ Stephen DNB, p. 212.

- ^ a b c d Fox, Christopher (2003). The Cambridge Companion to Jonathan Swift. Cambridge University Press. pp. 36–39.

- ^ a b Cody, David. "Jonathan Swift's Political Beliefs". Victorian Web. Archived from the original on 8 November 2018. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ^ Stephen DNB, pp. 212–215.

- ^ Stephen DNB, pp. 215–216.

- ^ Stephen DNB, p. 216.

- ^ Gregg, Edward (1980). Queen Anne. Yale University Press. pp. 352–353.

- ^ "Fasti Ecclesiae Hibernicae: The succession of the prelates Volume 2" Cotton, H. pp. 104–105: Dublin, Hodges & Smith, 1848–1878.

- ^ Gregg (1980), p. 353.

- ^ Stephen DNB, p. 215.

- ^ Stephen DNB, pp. 217–218.

- ^ Sir Walter Scott. Life of Jonathan Swift, vol. 1, Edinburgh 1814, pp. 281–282.

- ^ Ball, F. Elrington (1926). The Judges in Ireland 1221–1921, London: John Murray, vol. 2 pp. 103–105.

- ^ a b c Stephen DNB, p. 219.

- ^ Stephen DNB, p. 221.

- ^ "The Story of Civilization," vol. 8., 362.

- ^ a b Stephen DNB, p. 222.

- ^ Passmann, Dirk F. 2012. "Jonathan Swift as a Book-Collector: With a Checklist of Swift Association Copies." Swift Studies: The Annual of the Ehrenpreis Center 27: 7–68.

- ^ Foot, Michael (1981) Debts of Honour. Harper & Row, New York, p. 219.

- ^ Johnston, Denis (1959) In Search of Swift Hodges Figgis, Dublin

- ^ "Dictionary of Irish Biography". Archived from the original on 21 March 2022. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- ^ Concise Cambridge History of English Literature, 1970, p. 387.

- ^ De Breffny, Brian (1983). Ireland: A Cultural Encyclopedia. London: Thames and Hudson. p. 232.

- ^ Murry, op. cit., p. 150, quotes Steele's Preface to the collected edition of the first four volumes of The Tatler: "I have in the dedication of the first volume made my acknowledgements to Dr. Swift, whose pleasant writings in the name of Bickerstaff created an inclination in the town towards anything that could appear in the same disguise."

- ^ Elrington Ball. The Judges in Ireland, vol. 2 pp. 103–105.

- ^ Baltes, Sabine (2003). The Pamphlet Controversy about Wood's Halfpence (1722–25) and the Tradition of Irish Constitutional Nationalism. Peter Lang GmbH. p. 273.

- ^ Traynor, Jessica. "Irish v English prizefighters: eye-gouging, kicking and sword fighting". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 9 January 2020. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ Swift, Jonathan (2015). A Modest Proposal. London: Penguin. p. 29. ISBN 978-0141398181.

- ^ This work is often wrongly referred to as "A Critical Essay upon the Faculties of the Mind".

- ^ Rudd, Niall (Summer 2006). "Swift's 'On Poetry: A Rhapsody'". Hermathena. 180 (180): 105–120. JSTOR 23041663. Archived from the original on 30 July 2023. Retrieved 30 July 2023.

- ^ Jonathan, Swift (2007). The Benefit of Farting. Oneworld Classics. ISBN 9781847490315.

- ^ In the preface of the 1871 edition of Sesame and Lilies Ruskin mentions three figures from literary history with whom he feels an affinity: Guido Guinicelli, Marmontel and Dean Swift; see John Ruskin, Sesame and lilies: three lectures Archived 11 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Smith, Elder, & Co., 1871, p. xxviii.

- ^ "Politics vs. Literature: an examination of Gulliver's Travels"

- ^ Gabriele Griffin (2003). Who's Who in Lesbian and Gay Writing. Routledge. p. 244. ISBN 978-1134722099. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ Rowse, A. L. (1975). Jonathan Swift Major Prophet. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-01141-9.

- ^ Rowse, A. L. (1944). "XXVI: Jonathan Swift". The English Spirit: Essays in History and Literature. London: Macmillan. pp. 182–192.

- ^ Rowse, A. L. (1970). "Swift as Poet". In A. Norman Jeffares (ed.). Swift. Modern Judgements. Nashville and London: Aurora Publishers Incorporated. pp. 135–142. ISBN 0-87695-092-6.

- ^ Swift, Jonathan (1977). A. L. Rowse (ed.). Gulliver's Travels. London and Sydney: Pan Books. ISBN 0-330-25190-2.

- ^ Justin Hayford (12 January 2006). "The House That Swift Built". Performing Arts Review. Chicago Reader. Archived from the original on 9 February 2020. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ^ Arnott, Jake (2017). The Fatal Tree. Sceptre. ISBN 978-1473637740.

- ^ "What is the most popular Irish book?". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 2 December 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ^ Barnett, Louise (2007). Jonathan Swift in the Company of Women. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-19-518866-0. Archived from the original on 26 April 2023. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- ^ Smith, Sophie Shilleto. Dean Swift. Methuen & Company, 1910.

- ^ MathPages – Galileo's Anagrams and the Moons of Mars Archived 12 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Home – The Jonathan Swift Festival". The Jonathan Swift Festival. Archived from the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

References

[edit]- Damrosch, Leo (2013). Jonathan Swift : His Life and His World. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-16499-2.. Includes almost 100 illustrations.

- Delany, Patrick (1754). Observations Upon Lord Orrery's Remarks on the Life and Writings of Dr. Jonathan Swift. London: W. Reeve. OL 25612897M.

- Fox, Christopher, ed. (2003). The Cambridge Companion to Jonathan Swift. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00283-7.

- Ehrenpreis, Irvin (1958). The Personality of Jonathan Swift. London: Methuen. ISBN 978-0-416-60310-1.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help).- — (1962). Swift: The Man, His Works, and the Age. Vol. I: Mr. Swift and his Contemporaries. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-85830-1.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - — (1967). Swift: The Man, His Works, and the Age. Vol. II: Dr. Swift. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-85832-8.

- — (1983). Swift: The Man, His Works, and the Age. Vol. III: Dean Swift. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-85835-2.

- — (1962). Swift: The Man, His Works, and the Age. Vol. I: Mr. Swift and his Contemporaries. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-85830-1.

- Nokes, David (1985). Jonathan Swift, a Hypocrite Reversed: A Critical Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-812834-2.

- Orrery, John Boyle, Earl of (1752) [1751]. Remarks on the Life and Writings of Dr. Jonathan Swift (third, corrected ed.). London: Printed for A. Millar. OL 25612886M.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Stephen, Leslie (1882). Swift. English Men of Letters. New York: Harper & Brothers. OL 15812247W. Noted biographer succinctly critiques (pp. v–vii) biographical works by Lord Orrery, Patrick Delany, Deane Swift, John Hawkesworth, Samuel Johnson, Thomas Sheridan, Walter Scott, William Monck Mason, John Forester, John Barrett, and W.R. Wilde.

- Stephen, Leslie (1898). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 55. pp. 204–227.

- Wilde, W. R. (1849). The Closing Years of Dean Swift's Life. Dublin: Hodges and Smith. OL 23288983M.

- Samuel Johnson's "Life of Swift": JaffeBros Archived 7 November 2005 at the Wayback Machine. From his Lives of the Poets.

- William Makepeace Thackeray's influential vitriolic biography: JaffeBros Archived 7 November 2005 at the Wayback Machine. From his English Humourists of The Eighteenth Century.

- Sir Walter Scott Memoirs of Jonathan Swift, D.D., Dean of St. Patrick's, Dublin

. Paris: A. and W. Galignani, 1826.

. Paris: A. and W. Galignani, 1826. - Whibley, Charles (1917). Jonathan Swift: the Leslie Stephen lecture delivered before the University of Cambridge on 26 May 1917. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

External links

[edit]- "Gulliver's Travels' 'nonsense' language is based on Hebrew, claims scholar" by Alison Flood, The Guardian, 17 August 2015.

- Jonathan Swift Archived 10 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine at the Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive (ECPA) Archived 25 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 224–231.

- BBC audio file Archived 3 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine "Swift's A modest Proposal". BBC discussion. In our time.

- Jonathan Swift Archived 15 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- Swift, Jonathan (1667–1745) Dean of St Patrick's Dublin Satirist Archived 25 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine at the National Archives.

- The Arch C. Elias Collection, containing material by and about Jonathan Swift, at the Library of Trinity College Dublin.

Online works

[edit]- Works by Jonathan Swift in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by Jonathan Swift at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Jonathan Swift at the Internet Archive

- Works by Jonathan Swift at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by Jonathan Swift at Open Library

- Works by Jonathan Swift at The Online Books Page

Jonathan Swift

View on GrokipediaJonathan Swift (30 November 1667 – 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish satirist, essayist, poet, and Anglican cleric who served as Dean of St. Patrick's Cathedral in Dublin from 1713 until his death.[1] Born in Dublin to English parents shortly after his father's death, Swift was educated at Trinity College Dublin and ordained in 1695, later gaining prominence in London literary and political circles before returning to Ireland.[2] His most enduring achievement, Gulliver's Travels (1726), a satirical novel critiquing human folly, science, and politics through fantastical voyages, remains one of the most widely read works in English literature.[2] Swift's writings often employed biting irony to expose societal vices, religious corruption, and colonial exploitation, as seen in A Tale of a Tub (1704), a parody of religious enthusiasm, and A Modest Proposal (1729), a provocative essay feigning advocacy for Irish parents to sell their children as food to alleviate poverty and English absentee landlordism.[2][3] In political pamphlets like the Drapier's Letters (1724–1725), he rallied Irish opposition against a debased coinage scheme, forcing its abandonment and earning acclaim as a defender of Irish economic interests despite his clerical role under English establishment.[2] These efforts, alongside his management of St. Patrick's Cathedral and posthumous founding of a mental hospital via his estate, underscored his commitment to Irish welfare amid personal struggles with deafness, vertigo, and eventual mental decline.[2][1]

Early Life and Education

Birth and Family

Jonathan Swift was born on 30 November 1667 in Hoey's Court, Dublin, Ireland, the second child and only son of Jonathan Swift (c. 1640–1667) and Abigail Erick (c. 1642–1710).[4][5] His father, an attorney originally from Goodrich, Herefordshire, England, had relocated to Ireland in the early 1660s following the Restoration, securing a position as steward of the King's Inns in Dublin.[6] The elder Swift died in April 1667, approximately seven months before his son's birth, leaving the family without his income and plunging them into poverty.[7] Swift's mother, born in England to a Leicestershire family, struggled to support her children and returned to her homeland shortly after the birth, where she resided for much of Swift's early years.[8][7] Unable to provide adequately in Ireland, she placed the infant Swift in the guardianship of his paternal uncle, Godwin Swift (1628–1695), a Dublin lawyer and merchant who offered modest financial assistance but maintained a distant relationship with his nephew.[4] Godwin, the eldest of the Swift brothers, had himself emigrated from England amid the post-Civil War upheavals, reflecting the family's Protestant English roots and ties to Royalist networks, as evidenced by ancestral figures like the "cavaliero Swift" who supported the Stuart cause.[9][10] As an Anglo-Irish Protestant born into this transplanted English lineage, Swift grew up in a precarious household amid Dublin's volatile environment, where the Protestant settler community—bolstered by Cromwellian land redistributions and Williamite victories—faced ongoing economic pressures and cultural isolation from the Catholic majority.[4] His early dependence on extended family underscored the insecurities of such immigrant Protestant households, shaped by the legacies of 17th-century conquests and absentee English influences in Irish affairs.[10]Education at Kilkenny and Trinity College

Swift was enrolled at Kilkenny School, one of Ireland's premier institutions for classical education, at the age of six in 1673, remaining until 1682.[11] There, he received a rigorous grounding in Latin and Greek, demonstrating particular aptitude in languages and literature.[12] Among his contemporaries was William Congreve, the future playwright, with whom Swift formed a lasting acquaintance during their shared studies.[13] In June 1682, at age fourteen, Swift matriculated as a pensioner at Trinity College Dublin, Ireland's leading Protestant university, pursuing a curriculum centered on classical languages including Hebrew alongside mathematics and philosophy.[14] His time there was marked by disciplinary challenges and non-conformity with the college's stringent regulations, leading to frequent clashes with authorities.[11] Consequently, he received his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1686 ex speciali gratia—by special concession—rather than through standard examination, reflecting his intellectual promise amid behavioral independence.[11] Trinity's Anglican environment exposed Swift to orthodox Protestant theology and the works of Roman satirists such as Juvenal, whose indignant critiques of vice fostered his emerging affinity for sharp, moralistic commentary.[14] This classical immersion, building on Kilkenny's foundations, honed his command of rhetoric and irony, traits evident in his later output, while the institution's emphasis on ecclesiastical preparation aligned with his clerical trajectory.[14] He briefly pursued a Master of Arts but departed Dublin in 1689 amid rising tensions preceding the Williamite War, seeking opportunities in England.[11]Early Writings and Influences

Swift's initial literary output occurred during his residence at Moor Park as secretary to Sir William Temple from 1689 onward, where the diplomat's vast library—comprising classical texts, essays, and contemporary works—provided crucial exposure to ancient and modern learning that honed his satirical style.[15] His debut publication, the poem "Ode to the Athenian Society," printed in the February 1692 supplement to The Athenian Mercury, employed mock-heroic verse to laud the society's empirical inquiries while subtly ironizing pretensions to universal knowledge, revealing early command of irony and critique.[16] Other juvenilia from this period, such as occasional verses composed at Temple's estate, echoed these traits, blending admiration for intellectual patronage with undercurrents of detachment born from his subordinate role.[17] Financial precarity marked Swift's post-university years; after earning his B.A. from Trinity College Dublin in 1686 and briefly tutoring in Ireland, he relocated to England in 1688 amid limited prospects, relying on familial connections for Temple's employment to escape outright want.[2] Compounding this, vertigo attacks—retrospectively linked to Ménière's disease, involving dizziness, nausea, and auditory disturbances—first afflicted him in the early 1690s, recurring episodically and intensifying his alienation as an Irish Protestant dependent on English patrons.[18] Such circumstances cultivated a persistent outsider ethos, evident in his writings' emerging disdain for institutional hypocrisies and human folly, themes rooted in personal frustration rather than abstract philosophy. Swift's inaugural prose pamphlet, A Discourse of the Contests and Dissensions between the Nobles and the Commons in Athens and Rome (1697), anonymously advanced arguments against yielding ecclesiastical authority to dissenters, paralleling ancient republican strife to warn of societal fracture from factional concessions.[19] Drawing on Temple's essays defending classical antiquity, the tract critiqued corruption in power structures, prioritizing stability of established hierarchies over reformist agitation, and signaled his alignment with Anglican orthodoxy amid Ireland's religious tensions.[20]Career in England

Secretary to Sir William Temple

In 1689, following the disbandment of Trinity College amid political unrest in Ireland, Jonathan Swift joined the household of retired diplomat Sir William Temple at Moor Park in Surrey, England, serving as his secretary and amanuensis.[11] In this role, Swift managed Temple's extensive correspondence, assisted with organizing his library, and aided in preparing diplomatic papers and essays for publication, thereby acquiring practical knowledge of international negotiations and elite administrative practices.[11] These responsibilities immersed him in the intellectual and political milieu of Restoration England, including Temple's connections across partisan lines. Seeking ecclesiastical advancement amid frustrations with his subordinate status, Swift departed Moor Park around 1694 and returned to Ireland, where he was ordained as a priest in the Church of Ireland on 30 January 1695 at Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin.[11] He received the prebend of Kilroot in County Antrim, a rural and modestly remunerated position that offered limited influence and prospects, prompting dissatisfaction with the career trajectory available through Temple's patronage.[11] Efforts to secure preferment via Temple yielded insufficient support, contributing to tensions that briefly strained their relationship before Swift rejoined Moor Park in 1696 at Temple's invitation.[21] Swift's tenure exposed him to foundational debates in English letters and politics, particularly through Temple's advocacy in partisan circles and his 1690 Essay upon Ancient and Modern Learning, which asserted the superiority of classical authors over contemporary innovators in arts and sciences.[22] This work influenced Swift's emerging skepticism toward modern pretensions, fostering a preference for traditional erudition that informed his later critiques of intellectual hubris, while Temple's diplomatic background provided firsthand observation of Whig-Tory rivalries over policy and governance.[22]Initial Political and Literary Circles

Upon the death of Sir William Temple in January 1699, Swift remained in England to pursue ecclesiastical preferment through his connections, initially aligning pragmatically with Whig figures who dominated literary and political circles in London. His friendships with Joseph Addison and Richard Steele, key Whig writers, facilitated entry into these networks; by 1705, Swift enjoyed frequent intercourse with them, contributing poems such as "A Description of the Morning" and "A Description of a City Shower" to Steele's Tatler starting in 1709.[23] These contributions, including his first prose piece in Tatler No. 32 on June 23, 1709, showcased his satirical style amid the periodical's Whig-leaning commentary on society and politics, though Swift's involvement reflected opportunistic collaboration rather than deep ideological commitment.[24] Swift's literary experiments during this period included the anonymous publication of A Tale of a Tub in 1704, a prose satire targeting religious enthusiasm, corruptions in the Church, and the excesses of modern learning through the allegory of three brothers representing Catholicism, Anglicanism, and Puritanism.[25] Initially receiving acclaim for its wit, the work provoked controversy for its irreverent tone, with critics perceiving it as undermining Anglican orthodoxy despite Swift's defense in a 1710 "Apology" clarifying its intent to ridicule extremists while upholding the Church of England.[25] The tract's layered irony hindered preferment under Queen Anne, who viewed it unfavorably, underscoring Swift's precarious position as an Irish cleric navigating English elite opinion.[26] Concurrently, Swift's clerical duties at Laracor rectory in County Meath, to which he was appointed vicar in February 1700 alongside prebendary at St. Patrick's Cathedral, served as a financial fallback but highlighted the cultural chasm between his English aspirations and Irish reality; he resided there intermittently until 1713, delegating much parish work while prioritizing London connections that offered greater influence and patronage prospects.[27][11] This divide reinforced Swift's preference for English intellectual life, where pragmatic networking with Whig literati like Addison and Steele—precursors to broader satirical groups—advanced his reputation amid stalled career ambitions.[28]Association with Whigs and Disillusionment

Swift's entry into English political circles stemmed from his role as secretary to Sir William Temple, a leading Whig statesman and diplomat, whom he served at Moor Park from 1689 until Temple's death in 1699. This position exposed Swift to Whig principles, including support for the Glorious Revolution of 1688, constitutional limits on monarchical power, and opposition to absolute rule, aligning initially with his advocacy for a balanced government where the monarch acted as the "greatest servant of the nation" under laws derived from the people.[29][30] In late 1707, Swift traveled to London to lobby the Whig-dominated Godolphin ministry for the remission of first-fruits taxes on the Irish clergy, a concession aimed at alleviating financial burdens on the Church of Ireland amid Queen Anne's reign. His efforts, spanning November 1707 to April 1709, reflected temporary alignment with Whig leaders like Sidney Godolphin, whom he viewed as amenable to pragmatic reforms favoring the established Church. However, negotiations stalled as Whig policymakers conditioned relief on repealing the Sacramental Test Act, which barred dissenters from civil and military offices to safeguard Anglican dominance—a policy Swift deemed essential for ecclesiastical stability.[31][32] This period saw Swift articulate his Church-centric worldview in key writings, prioritizing Anglican establishment over partisan expediency. In Sentiments of a Church-of-England Man, composed in 1708 and reflecting his self-described moderate stance, he endorsed constitutional monarchy with checks on royal prerogative—such as parliamentary oversight to prevent oppression—while firmly upholding the Church's legal privileges against dissenter encroachments, warning that toleration beyond strict limits risked Presbyterian dominance and historical precedents of rebellion like that against Charles I in 1649. He critiqued both Whig and Tory extremes for fostering factionalism and materialism, where pursuits of wealth and power supplanted public virtue and divine trust, yet emphasized loyalty to the Church as transcending party labels.[30][30] Swift's A Project for the Advancement of Religion, and the Reformation of Manners, written in 1709 and dedicated to the Countess of Berkeley, further exposed tensions by diagnosing widespread moral decay—profanity among the vulgar, corruption in trades and offices, and clerical servility—under the prevailing administration, attributing it to lax enforcement of religious duties and vice's open toleration. He proposed crown-led reforms, including mandatory piety in court appointments and commissioners to suppress immorality with an annual £6,000 budget, accepting short-term hypocrisy as a lesser evil than unbridled vice, provided it fostered eventual genuine reform; implicitly, this indicted Whig governance for prioritizing party patronage over moral order.[33][33] Disillusionment crystallized from Whig policies perceived as subordinating Church integrity to dissenter appeasement and internal power struggles, evident in their reluctance to remit first-fruits without Test Act concessions and broader tolerance that Swift saw as eroding Anglican primacy in favor of factional gain. Rooted in a conviction that governance demanded moral and religious foundations over material or sectarian compromises, Swift's break highlighted his prioritization of ecclesiastical defense—viewing dissenters' historical disloyalty, from Puritan regicide to potential parliamentary majorities, as existential threats—over unwavering party allegiance, foreshadowing his later critiques without yet committing to Tory ranks.[29][30][34]Return to Ireland and Clerical Career

Ordination and Early Posts in Ireland

Swift was ordained deacon in the Church of Ireland on 28 October 1694 and priest on 9 May 1695 at St. Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin.[35] Shortly thereafter, in January 1695, he received appointment as prebendary of Kilroot in the Diocese of Connor, a rural benefice near Carrickfergus in County Antrim, which included a modest parish and residence.[27] However, Swift's tenure at Kilroot proved brief and restless; he resided there only intermittently during 1695–1696, finding the isolation and lack of intellectual stimulation incompatible with his ambitions, before resigning the prebend in December 1697 to resume service with Temple in England.[35] Upon Temple's death on 27 January 1699, Swift returned permanently to Ireland in the summer of that year, initially serving as chaplain and secretary to Lord Berkeley, one of the Lords Justices governing Ireland.[36] In March 1700, through Berkeley's influence, Swift secured the vicarage of Laracor in County Meath, near Trim, along with the adjacent rectories of Rahinstown and Hamrock, forming a consolidated living that provided an annual income of about £250.[11] He also held the prebend of Dunlavin in St. Patrick's Cathedral from 1700, though this was non-residential.[36] Unlike his experience at Kilroot, Swift actively resided at Laracor for much of the next decade, managing its glebe lands—approximately 40 acres—through practical improvements such as diking, planting, and constructing a flour mill on the premises, which generated additional revenue.[11] In his clerical duties at Laracor, Swift demonstrated a hands-on conservatism, catechizing local children, maintaining the church fabric, and providing direct relief to the poor amid widespread rural destitution exacerbated by absentee landlords and English trade restrictions.[37] His small congregation of fewer than 20 families afforded him leisure for reading and writing, yet the post underscored his growing frustration with Ireland's subordinate status under English policy, which he viewed as causally perpetuating economic stagnation through prohibitions on wool exports and manufacturing incentives.[11] This period marked Swift's initial immersion in Irish ecclesiastical and social realities, tempering his earlier hopes for preferment in England—repeatedly petitioned but unrealized—and laying groundwork for his later advocacy against policies that deepened colonial dependency.[36]Dean of St. Patrick's Cathedral

In April 1713, Swift received appointment as Dean of St. Patrick's Cathedral in Dublin as recompense for his Tory pamphleteering, notably The Conduct of the Allies.[38] This post, which he retained until his death on 19 October 1745, disappointed his ambitions for an English bishopric, constrained by his Irish nativity and the imminent Whig ascendancy under George I.[38] Arriving in Dublin in June 1713, he assumed leadership of the cathedral amid the Church of Ireland's precarious status in a predominantly Catholic country. As dean, Swift enforced pastoral discipline, mandating daily prayers, frequent Holy Communion, and rigorous financial oversight to safeguard the chapter's endowments against immediate depletion.[39] Post-1714 Tory collapse, he positioned himself as bulwark for Anglican privileges, resisting Whig initiatives like Test Act repeal that threatened the establishment's monopoly on civil office.[4] His tenure fortified St. Patrick's as a Protestant bastion, underscoring ecclesiastical resilience amid political marginalization. Swift's deanship intertwined clerical duty with proto-nationalist agitation, exemplified by the Drapier's Letters (1724–1725), pseudonymous tracts decrying William Wood's royal patent for Irish copper coinage—deemed a 360-tonne influx of base halfpence engineered for English profit at Ireland's expense.[40] These epistles mobilized Protestant merchants and gentry, framing the scheme as tyrannical imposition; public outcry prompted patent curtailment in September 1725.[41] This campaign revealed Swift's nuanced Anglo-Irish stance: vehement against Westminster's extractive policies eroding Irish autonomy, yet wedded to the Protestant Ascendancy's hegemony, excluding Catholic reclamation and Dissenting encroachments.[42] In testament to enduring institutional commitment, his 1745 will endowed £12,000 for St. Patrick's Hospital, earmarked for "imbeciles and lunatics," inaugurating Ireland's inaugural psychiatric facility (opened 1757).[43]Engagement with Irish Affairs

Swift's tenure as Dean of St. Patrick's Cathedral from 1713 positioned him to intervene in Irish economic and social crises, where he attributed Ireland's stagnation to a combination of restrictive English trade laws—such as the ban on exporting woolen manufactures—and the exploitative practices of absentee landlords who remitted rents to England, depleting local capital.[44] In a 1720 pamphlet, A Proposal for the Universal Use of Irish Manufacture, he urged Irish consumers to boycott English imports except coal, aiming to stimulate domestic industry and reverse the colony's dependence on England, which he calculated drained Ireland of over £500,000 annually through absenteeism and unequal trade.[45] This advocacy emphasized self-reliance within the existing constitutional framework rather than independence, linking economic revival to moral and industrious habits among the Irish populace. The Drapier's Letters (1724–1725), a series of seven anonymous pamphlets penned under the pseudonym M.B. Drapier, exemplified Swift's opposition to perceived English corruption in Irish governance. Prompted by a 1722 royal patent granting William Wood a monopoly to mint copper halfpence and farthings—valued at £100,800 over 14 years but criticized for poor quality and potential debasement of currency—Swift warned that the coinage would flood Ireland with substandard money, undermine trust in trade, and benefit Wood's cronies at Ireland's expense.[46] The letters mobilized drapers, shopkeepers, and farmers, framing the issue as a defense of Irish liberties against fraudulent patents, and culminated in widespread protests that pressured the English government to investigate via a royal commission in 1724; the patent was ultimately revoked in September 1725.[47] Far from advocating separatism, Swift used the campaign to promote constitutional petitioning and local manufacturing, arguing that English policies exacerbated Ireland's poverty while Irish compliance enabled it. In sermons delivered at St. Patrick's, Swift addressed famine and social decay as outcomes of both external exploitation and internal failings, such as idleness and factionalism among the Irish. In "A Sermon on the Causes of the Wretched Condition of Ireland" (circa 1720s), he enumerated trade barriers that reduced Ireland to "hewers of wood and drawers of water," alongside absentee landlords' extraction of rents—estimated to export £400,000–£600,000 yearly—and called for charity, frugality, and unity under the Church of Ireland to mitigate scarcity, rejecting blame solely on English neglect.[30] He dismissed revolutionary upheaval, favoring reforms like prohibiting absenteeism through parliamentary legislation and encouraging domestic consumption to foster economic resilience, while upholding loyalty to the constitutional monarchy as the path to stability.[44] These interventions underscored Swift's causal analysis: English policies initiated decline, but Irish moral lapses perpetuated it, necessitating Church-guided self-improvement over radical change.Political Advocacy and Tory Commitment

Shift from Whig to Tory Allegiance (1710)

In September 1710, Jonathan Swift arrived in London at the invitation of Robert Harley, the Tory leader and Speaker of the House of Commons, who sought to enlist Swift's pen amid the impending general election. Swift, previously aligned with Whig circles through his association with Sir William Temple and figures like Addison and Steele, had grown disillusioned with the Whig ministry's policies, particularly their handling of the Church of England. The trial of Henry Sacheverell in February-March 1710, where the High Church clergyman was impeached for sermons criticizing Whig toleration of Dissenters and occasional conformity, highlighted what Swift perceived as a Whig assault on ecclesiastical authority and orthodoxy.[48] Swift rejected absolutist notions like divine right of kings, a hallmark of High Toryism, but found common cause with moderate or "country" Tories in their opposition to ministerial corruption and the prolongation of the War of the Spanish Succession.[49] Swift's Journal to Stella, a series of letters begun on 9 September 1710 to Esther Johnson and Rebecca Dingley, meticulously records the Tory leadership's courtship, including multiple dinners with Harley (then elevated to Earl of Oxford) starting 7 October, where political discussions intensified.[50] These encounters, facilitated by intermediaries like Erasmus Lewis, Harley's secretary, convinced Swift of the Tories' commitment to ending the war and restoring Church influence, contrasting with Whig favoritism toward Dissenters and continental allies. By late October, as the general election unfolded—yielding a Tory landslide with approximately 340 seats to the Whigs' 170—Swift had committed to the new ministry, viewing the shift as a principled realignment driven by empirical failures of Whig governance rather than mere opportunism.[48] This transition crystallized in Swift's advocacy for peace, culminating in his 1711 pamphlet The Conduct of the Allies, which exposed alleged profiteering by John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough, through inflated war expenditures and dependency on Dutch allies, thereby justifying Tory negotiations at Utrecht.[51] The work's publication in November 1711 amplified Tory popularity by framing the war's continuation as elite self-interest, with sales exceeding 10,000 copies in weeks and influencing public sentiment toward the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht.[52] Swift's stance reflected causal consistency: his longstanding critique of factional excess and imperial overreach, evident in earlier writings, aligned with Tory realism on fiscal burdens—England's war costs nearing £70 million by 1710—over Whig idealism tied to grand alliances.[53]Role as Tory Pamphleteer

Swift became a key propagandist for the Tory ministry after aligning with Robert Harley (Earl of Oxford) and Henry St. John (Viscount Bolingbroke) in 1710, leveraging his writing to counter Whig criticisms and promote ministerial policies.[24] He assumed control of The Examiner, a pro-Tory weekly newspaper launched on August 3, 1710, and authored 33 consecutive issues from November 2, 1710, to June 7, 1711, systematically defending the administration's fiscal restraint, Church of England supremacy, and diplomatic overtures toward peace with France amid the War of the Spanish Succession.[54] These essays targeted Whig accusations of Jacobitism and corruption, portraying the Tories as stewards of national prosperity and constitutional order against partisan extremism.[55] Swift's pamphlet The Conduct of the Allies and of the Late Ministry (November 1711) extended this advocacy by critiquing Britain's war expenditures—exceeding £70 million since 1688—as disproportionately benefiting Dutch and Austrian interests over English commerce and security, urging termination of hostilities to avert bankruptcy.[24] Circulated widely with over 10,000 copies sold in weeks and endorsements from Tory leaders, it shifted parliamentary sentiment, contributing to the ministry's dissolution of the Whig-dominated previous parliament and bolstering support for separate peace negotiations.[56] This effort culminated in the Treaty of Utrecht, signed April 11, 1713, which secured British gains like the asiento slave-trading contract and Newfoundland fisheries while ending the continental conflict.[57] Swift's output also addressed domestic Tory priorities, including opposition to occasional conformity, whereby Protestant Dissenters evaded sacramental tests for office by nominal Anglican participation; he reinforced ministerial bills against this practice in The Examiner and allied tracts, viewing it as eroding ecclesiastical authority.[30] His labors earned private commendations and hopes for English preferment, yet yielded no formal rewards beyond his existing Irish deanery.[24] Queen Anne's death on August 1, 1714, precipitated the Tory regime's collapse under the Hanoverian Whig ascendancy, rendering Swift's partisanship a liability; denied English bishoprics or livings despite lobbying, he retreated permanently to Dublin's St. Patrick's Cathedral, interpreting the exclusion as punitive marginalization for his effective ministerial service.[58] This outcome highlighted the Whig establishment's consolidation, suppressing Tory voices through preferment denial rather than overt prosecution.[59]Critiques of Whig Policies, Dissenters, and Standing Armies