Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

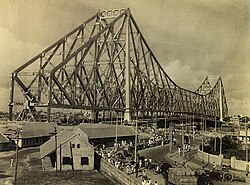

Howrah Bridge

View on Wikipedia

The Howrah Bridge is a balanced steel bridge over the Hooghly River in West Bengal, India. Commissioned in 1943,[9][11] the bridge was originally named the New Howrah Bridge, because it replaced a pontoon bridge at the same location linking both sides of Kolkata. Burrabazar is connected with Howrah rail terminal because of this bridge. On 14 June 1965, it was renamed Rabindra Setu after the Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore, who was the first Indian and Asian Nobel laureate.[11] It is still popularly known as the Howrah Bridge.

Key Information

The bridge is one of four on the Hooghly River and is a famous symbol of Kolkata and West Bengal. The other bridges are the Vidyasagar Setu (popularly called the Second Hooghly Bridge), the Vivekananda Setu and the relatively new Nivedita Setu. It carries a daily traffic of approximately 100,000 vehicles[12] and possibly more than 150,000 pedestrians,[10] easily making it the busiest cantilever bridge in the world.[13] The third-longest cantilever bridge at the time of its construction,[14] the Howrah Bridge is currently the sixth-longest bridge of its type in the world.[15]

History

[edit]1862 proposal by Turnbull

[edit]In 1862, the Government of Bengal asked George Turnbull, chief engineer of the East Indian Railway Company, to study the feasibility of bridging the Hooghly River. He had recently established the company's rail terminus in Howrah. He reported on 19 March, with large-scale drawings and estimates, that:[16]

- The foundations for a bridge at Calcutta would be at a considerable depth and cost because of the depth of the mud there.

- The impediment to shipping would be considerable.

- A good place for the bridge was at Pulta Ghat "about a dozen miles north of Calcutta" where a "bed of stiff clay existed at no great depth under the river bed".

- A suspended-girder bridge of five spans of 401 feet (122 m) and two spans 200 feet (61 m) would be ideal.

Pontoon bridge

[edit]

In view of the increasing traffic across the Hooghly river, a committee was appointed in 1855–56 to review alternatives for constructing a bridge across it.[17] The plan was shelved in 1859–60, to be revived in 1868, when it was decided that a bridge should be constructed and a newly appointed trust vested to manage it. The Calcutta Port Trust was founded in 1870,[9] and the Legislative department of the then Government of Bengal passed the Howrah Bridge Act in the year 1871 under the Bengal Act IX of 1871,[9][17] empowering the lieutenant-governor to have the bridge constructed with Government capital under the aegis of the Port Commissioners.

Eventually a contract was signed with Sir Bradford Leslie to construct a pontoon bridge. Different parts of the bridge were constructed in England and shipped to Calcutta, where they were assembled. The assembling period was fraught with problems. The bridge was considerably damaged by the great cyclone on 20 March 1874.[8] A steamer named Egeria broke from her moorings and collided head-on with the bridge, sinking three pontoons and damaging nearly 200 feet of the bridge.[8] The bridge was complete in 1874,[9] at a total cost of ₹2.2 million,[17] and opened to traffic on 17 October of that year.[8] The bridge was then 1528 ft long and 62 ft wide, with 7-foot wide pavements on either side.[9] Initially the bridge was periodically unfastened to allow steamers and other marine vehicles to pass through. Before 1906, the bridge used to be undone for the passage of vessels during daytime only. Since June of that year it started opening at night for all vessels except ocean steamers, which were required to pass through during daytime.[17] From 19 August 1879, the bridge was illuminated by electric lamp-posts, powered by the dynamo at the Mullick Ghat Pumping Station.[9] As the bridge could not handle the rapidly increasing load, the Port Commissioners started planning in 1905 for a new improved bridge.

Plans for a new bridge

[edit]In 1906[8] the Port Commission appointed a committee headed by R.S. Highet, chief engineer, East Indian Railway and W.B. MacCabe, chief engineer, Calcutta Corporation. They submitted a report stating that[9]

Bullock carts formed the eight - thirteenths of the vehicular traffic (as observed on 27 August 1906, the heaviest day's traffic observed in the port of Commissioners 16 days' Census of the vehicular traffic across the existing bridge). The roadway on the existing bridge is 48 feet wide except at the shore spans where it is only 43 feet in roadways, each 21 feet 6 inches wide. The roadway on the new bridge would be wide enough to take at least two lines of vehicular traffic and one line of trams in each direction and two roadways each 30 feet wide, giving a total width of 60 feet of road way which are quite sufficient for this purpose [...]

The traffic across the existing floating bridge Calcutta & Howrah is very heavy and it is obvious if the new bridge is to be on the same site as the existing bridge, then unless a temporary bridge is provided, there will be serious interruptions to the traffic while existing bridge is being moved to one side to allow the new bridge to be erected on the same site as the present bridge.

The committee considered six options:

- Large ferry steamers capable of carrying vehicular load (set up cost ₹900,000, annual cost ₹438,000)

- A transporters bridge (set up cost ₹2 million)

- A tunnel (set up cost ₹338.2 million, annual maintenance cost ₹1,779,000)

- A bridge on piers (set up cost ₹22.5 million)

- A floating bridge (set up cost ₹2,140,000, annual maintenance cost ₹200,000)

- An arched bridge

The committee eventually decided on a floating bridge. It extended tenders to 23 firms for its design and construction. Prize money of £3,000 (₹45,000, at the then exchange rate) was declared for the firm whose design would be accepted.[9]

Planning and estimation

[edit]

The initial construction process of the bridge was stalled due to World War I, although the bridge was partially renewed in 1917 and 1927. In 1921 a committee of engineers named the 'Mukherjee Committee' was formed, headed by R. N. Mukherji, Sir Clement Hindley, chairman of Calcutta Port Trust and J. McGlashan, Chief Engineer. They referred the matter to Sir Basil Mott, who proposed a single span arch bridge.[9] Charles Alfred O'Grady one of the Engineers

In 1922, set up, to which the Mukherjee Committee submitted its report. In 1926 the New Howrah Bridge Act passed. In 1930 the Goode Committee was formed, comprising S.W. Goode as president, S.N. Mallick, and W.H. Thompson, to investigate and report on the advisability of constructing a pier bridge between Calcutta and Howrah. Based on their recommendation, M/s. Rendel, Palmer and Tritton were asked to consider the construction of a suspension bridge of a particular design prepared by their chief draftsman Mr. Walton.[9] On basis of the report, a global tender was floated. The lowest bid came from a German company, but due to increasing political tensions between Germany and Great Britain in 1935, it was not given the contract.[8] The Braithwaite, Burn & Jessop Construction Co. was awarded the construction contract that year. The New Howrah Bridge Act was amended in 1935 to reflect this, and construction of the bridge started the next year.[9]

Construction

[edit]The bridge does not have nuts and bolts,[11][18] but was formed by riveting the whole structure. It consumed 26,500 tons of steel, out of which 23,000 tons of high-tensile alloy steel, known as Tiscrom, were supplied by Tata Steel.[8][19] The main tower was constructed with single monolith caissons of dimensions 55.31 m × 24.8 m[5][20] with 21 shafts, each 6.25 metre square.[21] The Chief Engineer of the Port Trust, Mr. J. McGlashan, wanted to replace the pontoon bridge, with a permanent structure, as the present bridge interfered with north–south river traffic. Work could not be started as World War I (1914–1918) broke out. Then in 1926 a commission under the chairmanship of Sir R. N. Mukherjee recommended a suspension bridge of a particular type to be built across the River Hoogly. The bridge was designed by one Mr. Walton of M/s Rendel, Palmer & Tritton. The order for construction and erection was placed on M/s.Cleveland Bridge & Engineering Company in 1939. Again World War II (1939–1945) intervened. All the steel that was to come from England were diverted for war effort in Europe. Out of 26,000 tons of steel, that was required for the bridge, only 3000 tons were supplied from England. In spite of the Japanese threat, the then (British) government of India pressed on with the construction. Tata Steel were asked to supply the remaining 23,000 tons of high tension steel. The Tatas developed the quality of steel required for the bridge and called it Tiscrom. The entire 23,000 tons was supplied in time. The fabrication and erection work was awarded to a local engineering firm of Howrah: the Braithwaite, Burn & Jessop Construction Co. The two anchorage caissons were each 16.4 m by 8.2 m, with two wells 4.9 m square. The caissons were so designed that the working chambers within the shafts could be temporarily enclosed by steel diaphragms to allow work under compressed air if required.[21] The caisson at Kolkata side was set at 31.41 m and that at Howrah side at 26.53 m below ground level.[5]

One night, during the process of grabbing out the muck to enable the caisson to move, the ground below it yielded, and the entire mass plunged two feet, shaking the ground. The impact of this was so intense that the seismograph at Kidderpore registered it as an earthquake and a Hindu temple on the shore was destroyed, although it was subsequently rebuilt.[22] While muck was being cleared, numerous varieties of objects were brought up, including anchors, grappling irons, cannons, cannonballs, brass vessels, and coins dating back to the East India Company. The job of sinking the caissons was carried out round-the-clock at a rate of a foot or more per day.[22] The caissons were sunk through soft river deposits to a stiff yellow clay 26.5 m below ground level. The accuracy of sinking the huge caissons was exceptionally precise, within 50–75 mm of the true position. After penetrating 2.1 m into clay, all shafts were plugged with concrete after individual dewatering, with some 5 m of backfilling in adjacent shafts.[21] The main piers on the Howrah side were sunk by open wheel dredging, while those on the Kolkata side required compressed air to counter running sand. The air pressure maintained was about 40 lbs per square inch (2.8 bar), which required about 500 workers to be employed.[13] Whenever excessively soft soil was encountered, the shafts symmetrical to the caisson axes were left unexcavated to allow strict control. In very stiff clays, a large number of the internal wells were completely undercut, allowing the whole weight of the caisson to be carried by the outside skin friction and the bearing under the external wall. Skin friction on the outside of the monolith walls was estimated at 29 kN/m2 while loads on the cutting edge in clay overlying the founding stratum reached 100 tonnes/m.[21] The work on the foundation was completed in November 1938.

By the end of 1940, the erection of the cantilevered arms was commenced and was completed in mid-summer of 1941. The two halves of the suspended span, each 282 feet (86 m) long and weighing 2,000 tons, were built in December 1941. The bridge was erected by commencing at the two anchor spans and advancing towards the center, with the use of creeper cranes moving along the upper chord. 16 hydraulic jacks, each of which had an 800-ton capacity, were pressed into service to join the two halves of the suspended span.[14]

The entire project cost ₹25 million (£2,463,887).[9] The project was a pioneer in bridge construction, particularly in India, but the government did not have a formal opening of the bridge due to fears of attacks by Japanese planes fighting the Allied Powers. Japan had attacked the United States at Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941. The first vehicle to use the bridge was a solitary tram.[8]

The bridge is regarded as the "gateway to Kolkata," as it connects the city to Howrah Station.[23]

Description

[edit]Specifications

[edit]

When commissioned in 1943, Howrah was the third-longest cantilever bridge in the world,[14] behind Pont de Québec (549 metres (1,801 ft)) in Canada and Forth Bridge (521 metres (1,709 ft)) in Scotland. It has since been surpassed by three bridges, making it the sixth-longest cantilever bridge in the world in 2013. It is a suspension type balanced cantilever[5] bridge, with a central span 1,500 feet (460 m) between centers of main towers and a suspended span of 564 feet (172 m). The main towers are 280 feet (85 m) high above the monoliths and 76 feet (23 m) apart at the top. The anchor arms are 325 feet (99 m) each, while the cantilever arms are 468 feet (143 m) each.[7] The bridge deck hangs from panel points in the lower chord of the main trusses with 39 pairs of hangers.[5] The roadways beyond the towers are supported from ground, leaving the anchor arms free from deck load. The deck system includes cross girders suspended between the pairs of hangers by a pinned connection.[7] Six rows of longitudinal stringer girders are arranged between cross girders. Floor beams are supported transversally on top of the stringers,[7] while themselves supporting a continuous pressed steel troughing system surfaced with concrete.[5]

The longitudinal expansion and lateral sway movement of the deck are taken care of by expansion and articulation joints. There are two main expansion joints, one at each interface between the suspended span and the cantilever arms and there are others at the towers and at the interface of the steel and concrete structures at both approach.[5] There are total of eight articulation joints, three at each of the cantilever arms and one each in the suspended portion. These joints divide the bridge into segments with vertical pin connection between them to facilitate rotational movements of the deck.[5] The bridge deck has longitudinal ruling gradient of 1 in 40 from either end, joined by a vertical curve of radius 4,000 feet (1,200 m). The cross gradient of the deck is 1 in 48 between kerbs.[5]

Traffic

[edit]

| Traffic flow for fast moving heavy vehicles[12] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Trams | Buses/vans | Trucks |

| 1959 | 13% | 41% | 46% |

| 1986 | 4% | 80% | 16% |

| 1990 | 3% | 82% | 15% |

| 1992 | 2% | 80% | 18% |

| 1999 | - | 89% | 11% |

| Traffic flow for fast moving light vehicles[12] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Two-wheelers/autos | Cars/taxis |

| 1959 | 2.47% | 97.53% |

| 1986 | 24% | 76% |

| 1990 | 27% | 73% |

| 1992 | 26% | 74% |

| 1999 | 20% | 80% |

The bridge serves as the gateway to Kolkata, connecting it to the Howrah Station, which is one of the five intercity train terminus stations serving Howrah and Kolkata. As such, it carries the near entirety of the traffic to and from the station, taking its average daily traffic close to nearly 150,000 pedestrians and 100,000 vehicles.[10] In 1946, a census of the daily traffic was taken, which counted 27,400 vehicles, 121,100 pedestrians and 2,997 cattle.[13] The bulk of the vehicular traffic comes from buses and cars. Prior to 1993, the bridge also carried trams. Trams departed from the terminus at Howrah station towards Sealdah, Rajabazar, Shyambazar, High Court, Dalhousie Square, Park Circus, Ballygunge, and Tollygunge. In 1993, tram service on the bridge was discontinued due to the increasing load on the structure. However, the bridge still continues to carry much more than the expected load. A 2007 report revealed that nearly 90,000 vehicles were plying on the bridge daily (15,000 of which were goods-carrying), though its load-bearing capacity is only 60,000.[24] One of the main reasons for the overloading was that, although vehicles carrying up to 15 tonnes are allowed on the structure, vehicles with 12-18 wheels and carrying loads up to 25 tonnes often plied on it. From 31 May 2007 onwards, overloaded trucks were banned from crossing the bridge and were redirected to the Vidyasagar Setu instead.[25] The road is flanked by footpaths 15 feet (4.6 m) wide, which are thronged with pedestrians.[5]

Maintenance

[edit]

The Kolkata Port Trust (KoPT) is vested with the maintenance of the bridge. The bridge has been subject to damage from vehicles due to rash driving, and corrosion due to atmospheric conditions and biological wastes. In October 2008, 6 high-tech surveillance cameras were placed to monitor the entire 705 metres (2,313 ft) long and 30 metres (98 ft) wide structure from the control room. Two of the cameras were placed under the floor of the bridge to track the movement of barges, steamers and boats on the river, while the other four were fixed to the first layer of beams — one at each end and two in the middle — to monitor vehicle movements. This was in response to substantial damage caused to the bridge from collisions with vehicles, so that compensation could be claimed from the miscreants.[26]

Corrosion has been caused by bird droppings and human spitting. An investigation in 2003 revealed that as a result of prolonged chemical reaction caused by continuous collection of bird excreta, several joints and parts of the bridge were damaged.[10] As an immediate measure, the Kolkata Port Trust engaged contractors to regularly clean the bird droppings, at an annual expense of ₹500,000 (US$5,900). In 2004, KoPT spent ₹6.5 million (US$77,000) to paint the entirety of 2.2 million square metres (24 million square feet) of the bridge. Two coats of aluminium paint, with a primer of zinc chromate before that, was applied on the bridge, requiring a total of 26,500 litres of paint.[27]

The bridge is also considerably damaged by pedestrians spitting out acidic, lime-mixed stimulants (gutka and paan).[28] A technical inspection by Port Trust officials in 2011 revealed that spitting had reduced the thickness of the steel hoods protecting the pillars from six to less than three millimeters since 2007.[29][30] The hangers need those hoods at the base to prevent water seeping into the junction of the cross-girders and hangers, and damage to the hoods can jeopardize the safety of the bridge. KoPT announced that it will spend ₹2 million (US$24,000) on covering the base of the steel pillars with fibreglass casing to prevent spit from corroding them.[31]

On 24 June 2005, a private cargo vessel M V Mani, belonging to the Ganges Water Transport Pvt. Ltd, while trying to pass under the bridge during high tide, had its funnel stuck underneath for three hours, causing substantial damage worth about ₹15 million to the stringer and longitudinal girder of the bridge.[32] Some of the 40 cross-girders were also broken. Two of four trolley guides, bolted and welded with the girders, were extensively damaged. Nearly 350 metres (1,150 ft) of 700 metres (2,300 ft) of the track were twisted beyond repair.[33] The damage was so severe that KoPT requested help from Rendall-Palmer & Tritton Limited, the original consultant on the bridge from UK. KoPT also contacted SAIL for 'matching steel' used during its construction in 1943.[34] For the repair, which cost around ₹5 million (US$59,000), about 8 tonnes of steel was used. The repairs were completed in early 2006.[35]

Cultural significance

[edit]

The bridge has been shown in numerous films, such as Bimal Roy's 1953 film Do Bigha Zamin, Ritwik Ghatak's Bari Theke Paliye in 1958, Satyajit Ray's Parash Pathar in the same year, Mrinal Sen's Neel Akasher Neechey in 1959, Shakti Samanta's Howrah Bridge (1958), that featured the famous song Mera Naam Chin Chin Chu and China Town (1962) and Amar Prem (1971), Amar Jeet's 1965 Teen Devian in 1965, Mrinal Sen's 1972 National Award winning Bengali film Calcutta 71 and Sen's Calcutta Trilogy its sequel in 1973, Padatik, Richard Attenborough's 1982 Academy Award winning film Gandhi, Goutam Ghose's 1984 Hindi film Paar, Raj Kapoor's Ram Teri Ganga Maili in 1985, Nicolas Klotz's The Bengali Night in 1988, Roland Joffé's English language film City of Joy in 1992, Florian Gallenberger's Bengali film Shadows of Time in 2004, Mani Ratnam's Bollywood film Yuva in 2004, Pradeep Sarkar's 2005 Bollywood film Parineeta, Subhrajit Mitra's 2008 Bengali film Mon Amour: Shesher Kobita Revisited, Mira Nair's 2006 film The Namesake, Blessy's 2008 Malayalam Film Calcutta News, Surya Sivakumar's 2009 Tamil film Aadhavan, Imtiaz Ali's 2009 Hindi film Love Aaj Kal, Abhik Mukhopadhyay's 2010 Bengali film Ekti Tarar Khonje, Sujoy Ghosh's 2012 Bollywood film Kahaani, Anurag Basu's 2012 Hindi film Barfi!, Riingo Banerjee's 2012 Bengali film Na Hannyate, Rana Basu's 2013 Bengali film Namte Namte, and Ali Abbas Zafar's 2014 Hindi film Gunday, 2015 YRF release from director Dibakar Banerjee's Detective Byomkesh Bakshy!, and even the 2024 Hindi hit Bhool Bhulaiyaa 3. Shoojit Sircar's Piku also features some scenes on this iconic bridge. The bridge was also featured in Garth Davis' Academy Award-nominated 2016 film Lion. Anvita Dutt's 2022 movie Qala features some fictional scenes of the bridge's construction.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Howrah Bridge Review". Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ "Howrah Bridge Map". Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- ^ Helen Schreider; Frank Schreider (October 1960). "From The Hair Of Siva". National Geographic. 118 (4): 445–503.

- ^ "Howrah Bridge Maintenance". Archived from the original on 18 November 2011. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Bridge Details". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ a b c "Howrah Bridge". Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ a b c d "Howrah Bridge". Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "River Ganges". Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "History of the Howrah Bridge". Archived from the original on 13 April 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ a b c d "Bird droppings gnaw at Howrah bridge frame". The Times of India. 29 May 2003. Archived from the original on 16 June 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ a b c "Howrah Bridge – The Bridge without Nuts & Bolts!". Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ a b c "Flow of Traffic on an average week day (8AM to 8 PM)". Archived from the original on 18 August 2011. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ a b c "Hosanna to Howrah Bridge!". Archived from the original on 17 November 2011. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ a b c Victor D. Johnson (2007). Essentials Of Bridge Engineering. Oxford & Ibh Publishing Co. Pvt Ltd. p. 259.

- ^ Durkee, Jackson (24 May 1999), National Steel Bridge Alliance: World's Longest Bridge Spans (PDF), American Institute of Steel Construction, Inc, archived from the original (PDF) on 1 June 2002, retrieved 2 January 2009

- ^ Diaries of George Turnbull held in Cambridge University, England.

- ^ a b c d "Howrah District (1909)". Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ "Howrah Bridge". Archived from the original on 28 October 2011. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ Kasturi Rangan (2003). The Shaping of Indian Science: 1914-1947. Universities Press. p. 494.

- ^ Ponnuswamy (2007). Bridge Engineering. Tata Mcgraw Hill Education Private Limited. p. 304.

- ^ a b c d William Warren; Luca Invernizzi Tettoni; Luca Invernizzi (2001). Singapore, city of gardens. Periplus Editions. p. 369.

- ^ a b Das, Soumitra (6 July 2008). "Cat's cradle of steel". The Telegraph. Calcutta, India. Archived from the original on 3 February 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ Naskar, Nemai (10 March 2025). "Howrah Bridge: History, Facts & Best Views". Trip Musing. Retrieved 10 March 2025.

- ^ "Howrah Bridge and Second Hooghly Bridge: A Comprehensive Comparative Study" (PDF). Calcutta, India. 9 September 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ^ "Howrah bridge ban". The Telegraph. Calcutta, India. 14 April 2007. Archived from the original on 3 February 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ Mandal, Sanjay (15 May 2010). "Bridge bleeds, blow by blow". The Telegraph. Calcutta, India. Archived from the original on 3 February 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ Sengupta, Swati (17 September 2004). "Calcutta icon, painted and lit- October makeover for Howrah bridge". The Telegraph. Calcutta, India. Archived from the original on 3 February 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ Burke, jason (26 May 2010). "Spit threatens Indian bridge". The Guardian. New Delhi. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ^ Bhattasali, Amitabha (23 November 2011). "Scheme to save Calcutta's Howrah Bridge from spit". Kolkata: BBC News. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ^ "Spit Threatens Busy Calcutta Bridge". Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ Mandal, Sanjay (14 November 2011). "Extra cover for spittoon bridge". The Telegraph. Calcutta, India. Archived from the original on 3 February 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ "Howrah's first: Ship stuck under". The Times of India. 24 June 2005. Archived from the original on 16 June 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ "A BARGE RAMS INTO THE BRIDGE IN A RARE ACCIDENT". Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ "British consultants contacted for repair of Howrah Bridge | news.outlookindia.com". Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 13 September 2012.

- ^ Mandal, Sanjay (2 January 2006). "Bridge under barge stress". The Telegraph. Calcutta, India. Archived from the original on 3 February 2013.

External links

[edit]- Official Website of Howrah Bridge, maintained by Calcutta Port Trust

- Picture of old Howrah Bridge

- Photos of Howrah Bridge

- "Howrah Bridge". New Delhi: National Archives of India. 1871. PR_000004001277.

Howrah Bridge

View on GrokipediaHistory

Early Proposals and Temporary Structures

In 1862, the Government of Bengal commissioned George Turnbull, chief engineer of the East Indian Railway Company, to assess the feasibility of constructing a permanent bridge across the Hooghly River to replace the existing ferry services connecting Calcutta and Howrah. Turnbull's study highlighted significant challenges, including the deep mud deposits at the proposed Calcutta site, which would necessitate expensive foundations at considerable depth. He estimated the costs as prohibitively high and recommended an alternative location at Palta Ghat, about 12 miles north, where stiffer clay beds would allow for a more viable suspended-girder design with spans of 401 feet and 200 feet; however, the proposal was ultimately rejected due to the overall expense and logistical concerns.[4][5] As an interim measure, the Bengal government established the first pontoon bridge in 1874, designed by Sir Bradford Leslie, chief engineer of the Eastern Bengal Railway, to address the growing demand for reliable cross-river transport amid rising commercial traffic. Constructed at a cost of Rs. 2.2 million, the floating structure spanned 1,528 feet with a 48-foot roadway and two 7-foot footways, using 26 iron pontoons moored by chains, and was opened to traffic on October 17, 1874, under the management of the Calcutta Port Commissioners. This bridge operated for nearly seven decades until 1943, enduring initial damages like a cyclone-induced collision in March 1874 that sank three pontoons, but requiring periodic openings for river navigation.[6][7][4] The evolution of temporary crossing solutions began in the 1850s with steam ferries handling passengers and goods between Calcutta and Howrah, which proved inadequate as industrial growth intensified river traffic and delays. By the late 19th century, these ferries gave way to the 1874 pontoon bridge as a more stable floating option, which itself underwent adaptations in the early 20th century, including electrical illumination in 1879 and routine night openings from 1906 to accommodate shipping. However, by the 1920s and 1930s, repeated silting of the Hooghly Riverbed, flood damages, and the structure's inability to support escalating vehicular and pedestrian loads—exacerbated by World War II demands—rendered it obsolete, paving the way for plans toward a permanent bridge.[8][7][6]Planning and Design Process

By the 1920s, surging vehicular and pedestrian traffic across the Hooghly River—fueled by industrial and commercial expansion in Calcutta and Howrah—overwhelmed the century-old pontoon bridge, prompting the Calcutta Port Commissioners to prioritize a permanent replacement.[1] In 1921, the Port Commissioners formed the Mookerjee Committee of engineers, chaired by Sir Rajendra Nath Mookerjee, which conducted feasibility studies and unanimously recommended a high-level cantilever bridge to handle projected loads without obstructing river navigation.[1] This recommendation addressed the pontoon's limitations during monsoons and tides, where it often had to be dismantled, disrupting connectivity.[9] The Howrah Bridge Act of 1926 formalized the project by creating the New Howrah Bridge Commission (identical to the Port Commissioners) and authorizing land acquisition and funding mechanisms.[1] To refine the design, the Commission invited competitive proposals in the late 1920s, offering a prize of £3,000 for the most viable engineering solution, though initial efforts were delayed by economic constraints.[9] In 1929, British firm Rendel, Palmer & Tritton was appointed as consulting engineers, tasked with detailed planning after earlier consultations with experts like Basil Mott.[1] Rendel, Palmer & Tritton's team undertook comprehensive site surveys starting in 1929, building on 1921 assessments by the Port Commissioners, to evaluate riverbed conditions and alignment.[1] Soil analysis revealed hard clay foundations at 97 feet below the Calcutta bank and 79 feet at Howrah, with bearing capacities of 5.5 to 16 tons per square foot, confirming the site's suitability for massive piers without extensive dredging.[1] These studies led to the final cantilever design selection in 1935, featuring a 1,500-foot central span and balanced arms, optimized for seismic stability and wind loads in the region.[1] The engineers estimated 26,500 tons of high-tensile steel would be required, prioritizing corrosion-resistant alloys to withstand the humid, saline environment.[1] Tenders for fabrication and erection were issued in December 1934, with submissions due by April 1935, attracting bids from international firms including those from the UK, Germany, and India.[1] Three proposals adhered to the official cantilever design, while alternatives like bascule or suspension were considered but rejected for cost and navigational reasons.[1] In 1936, the British Indian government approved the project budget at a preliminary estimate of £2,656,999 (about Rs 31,542,665), with breakdowns allocating roughly 60% to materials (primarily steel at Rs 12 crore), 25% to labor and erection, and reserves for contingencies amid rising pre-war material prices.[1] The lowest compliant bid from Cleveland Bridge & Engineering Co. was accepted at Rs 20,973,099, incorporating adjustments for potential wartime steel shortages and inflation.[1]Construction and Opening

Construction of the Howrah Bridge began in 1936, following the award of the contract to the British firm Cleveland Bridge & Engineering Company for erection and overall construction, with local fabrication handled by Braithwaite, Burn & Jessop Construction Company Limited in four workshops in Calcutta (now Kolkata). The steel components, totaling 26,500 tons, were primarily supplied by Tata Iron and Steel Company, using high-tensile Tiscrom steel, while a smaller portion came from England. Assembly relied entirely on riveted construction, with no nuts or bolts used, ensuring a robust cantilever structure assembled on-site over the Hooghly River.[1][2] The project faced significant delays due to World War II, as material shortages arose from the diversion of steel and resources to the Allied war effort, including fears of Japanese attacks on Calcutta in 1942–1943. Despite these challenges, the steelwork was completed by the end of 1942, allowing the bridge to be finalized amid wartime constraints.[1][2] The bridge was opened to the public on February 3, 1943, without a formal ceremony or public fanfare due to the ongoing war and security concerns; instead, it was inaugurated quietly at night when a solitary tramcar rolled across from the Calcutta end to the Howrah station end, marking the initial public access for vehicular and pedestrian traffic.[1][2][10] Originally named the New Howrah Bridge to distinguish it from its pontoon predecessor, it was renamed Rabindra Setu on June 14, 1965, in honor of the renowned Bengali poet and Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore, though the name Howrah Bridge remains widely used in common parlance.[2][10]Design and Engineering

Architectural Features

The Howrah Bridge employs a balanced cantilever truss design, constructed entirely from riveted steel without nuts or bolts, which enables a central span of 457 meters without the need for piers in the riverbed, thereby facilitating uninterrupted navigation for vessels on the Hooghly River. This configuration relies on high-tensile steel, specifically Tiscrom alloy steel with a tensile strength of 37 to 43 tons per square inch, to resist the strong currents of the Hooghly and potential seismic activity through robust pier foundations capable of angular distortion. The cantilever arms project from towers on each bank, balancing the load across the span while distributing forces back to the anchorages, ensuring structural stability under dynamic river conditions.[1][11][12] Key structural components include two 99-meter anchor arms on each side, which secure the cantilevers against backward pull, and a suspended span connecting the cantilever tips. The bridge deck is supported by 39 pairs of hangers from the lower chord of the main trusses, with cross girders and longitudinal stringer girders forming a lattice-like framework to carry the roadway and footpaths. To combat corrosion from the humid, saline environment near the river, the steel members are protected by initial red lead paint followed by aluminum paint over a zinc chromate primer. This load distribution via the cantilever system transfers vertical and horizontal forces efficiently through the truss lattice to the ground anchors, minimizing stress concentrations.[1][11][12] Among its innovations, the bridge incorporates expansion joints at critical interfaces, allowing for thermal expansion and contraction due to temperature fluctuations, preventing buckling or undue stress. At the time of its completion in 1943, it ranked as the world's third-longest cantilever bridge, showcasing advanced engineering for its era in achieving such a span without intermediate supports.[1][11]Technical Specifications

The Howrah Bridge features a total length of 705 meters between abutments, a roadway width of 21.6 meters accommodating six vehicular lanes, a tower height of 82 meters, and a navigational clearance of 19.5 meters (64 feet) above the Hooghly River's high water level.[11][1] Its main span measures 457.2 meters.[2] The bridge's cantilever design facilitates this extended main span without intermediate supports over the waterway.[1]| Specification | Details |

|---|---|

| Total Length | 705 meters |

| Width | 21.6 meters (roadway) plus two 4.6-meter footpaths added in 1964 |

| Tower Height | 82 meters |

| Clearance Above High Water | 19.5 meters (64 feet) |

| Main Span | 457.2 meters |

| Hangers | 39 pairs |

| Vehicular Lanes | 6 |

| Coordinates | 22°35′06″N 88°20′49″E |