Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hubble's law

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Physical cosmology |

|---|

|

Hubble's law, also known as the Hubble–Lemaître law,[1] is the observation in physical cosmology that galaxies are moving away from Earth at speeds proportional to their distance. In other words, the farther a galaxy is from the Earth, the faster it moves away. A galaxy's recessional velocity is typically determined by measuring its redshift, a shift in the frequency of light emitted by the galaxy.

The discovery of Hubble's law is attributed to work published by Edwin Hubble in 1929,[2][3][4] but the notion of the universe expanding at a calculable rate was first derived from general relativity equations in 1922 by Alexander Friedmann. The Friedmann equations showed the universe might be expanding, and presented the expansion speed if that were the case.[5] Before Hubble, astronomer Carl Wilhelm Wirtz had, in 1922[6] and 1924,[7] deduced with his own data that galaxies that appeared smaller and dimmer had larger redshifts and thus that more distant galaxies recede faster from the observer. In 1927, Georges Lemaître concluded that the universe might be expanding by noting the proportionality of the recessional velocity of distant bodies to their respective distances. He estimated a value for this ratio, which—after Hubble confirmed cosmic expansion and determined a more precise value for it two years later—became known as the Hubble constant.[8][9][10][11][12] Hubble inferred the recession velocity of the objects from their redshifts, many of which were earlier measured and related to velocity by Vesto Slipher in 1917.[13][14][15] Combining Slipher's velocities with Henrietta Swan Leavitt's intergalactic distance calculations and methodology allowed Hubble to better calculate an expansion rate for the universe.[16]

Hubble's law is considered the first observational basis for the expansion of the universe, and is one of the pieces of evidence most often cited in support of the Big Bang model.[8][17] The motion of astronomical objects due solely to this expansion is known as the Hubble flow.[18] It is described by the equation v = H0D, with H0 the constant of proportionality—the Hubble constant—between the "proper distance" D to a galaxy (which can change over time, unlike the comoving distance) and its speed of separation v, i.e. the derivative of proper distance with respect to the cosmic time coordinate.[a] Though the Hubble constant H0 is constant at any given moment in time, the Hubble parameter H, of which the Hubble constant is the current value, varies with time, so the term constant is sometimes thought of as somewhat of a misnomer.[19][20]

The Hubble constant is most frequently quoted in km/s/Mpc, which gives the speed of a galaxy 1 megaparsec (3.09×1019 km) away as 70 km/s. Simplifying the units of the generalized form reveals that H0 specifies a frequency (SI unit: s−1), leading the reciprocal of H0 to be known as the Hubble time (14.4 billion years). The Hubble constant can also be stated as a relative rate of expansion. In this form H0 = 7%/Gyr, meaning that, at the current rate of expansion, it takes one billion years for an unbound structure to grow by 7%.

Discovery

[edit]

A decade before Hubble made his observations, a number of physicists and mathematicians had established a consistent theory of an expanding universe by using Einstein field equations of general relativity. Applying the most general principles to the nature of the universe yielded a dynamic solution that conflicted with the then-prevalent notion of a static universe.

Slipher's observations

[edit]In 1912, Vesto M. Slipher measured the first Doppler shift of a "spiral nebula" (the obsolete term for spiral galaxies) and soon discovered that almost all such objects were receding from Earth. He did not grasp the cosmological implications of this fact, and indeed at the time it was highly controversial whether or not these nebulae were "island universes" outside the Milky Way galaxy.[22][23]

FLRW equations

[edit]In 1922, Alexander Friedmann derived his Friedmann equations from Einstein field equations, showing that the universe might expand at a rate calculable by the equations.[24] The parameter used by Friedmann is known today as the scale factor and can be considered as a scale invariant form of the proportionality constant of Hubble's law. Georges Lemaître independently found a similar solution in his 1927 paper discussed in the following section. The Friedmann equations are derived by inserting the metric for a homogeneous and isotropic universe into Einstein's field equations for a fluid with a given density and pressure. This idea of an expanding spacetime would eventually lead to the Big Bang and Steady State theories of cosmology.

Lemaître's equation

[edit]In 1927, two years before Hubble published his own article, the Belgian priest and astronomer Georges Lemaître was the first to publish research deriving what is now known as Hubble's law. According to the Canadian astronomer Sidney van den Bergh, "the 1927 discovery of the expansion of the universe by Lemaître was published in French in a low-impact journal. In the 1931 high-impact English translation of this article, a critical equation was changed by omitting reference to what is now known as the Hubble constant."[25] It is now known that the alterations in the translated paper were carried out by Lemaître himself.[10][26]

Shape of the universe

[edit]Before the advent of modern cosmology, there was considerable talk about the size and shape of the universe. In 1920, the Shapley–Curtis debate took place between Harlow Shapley and Heber D. Curtis over this issue. Shapley argued for a small universe the size of the Milky Way galaxy, and Curtis argued that the universe was much larger. The issue was resolved in the coming decade with Hubble's improved observations.

Cepheid variable stars outside the Milky Way

[edit]Edwin Hubble did most of his professional astronomical observing work at Mount Wilson Observatory,[27] home to the world's most powerful telescope at the time. His observations of Cepheid variable stars in "spiral nebulae" enabled him to calculate the distances to these objects. Surprisingly, these objects were discovered to be at distances which placed them well outside the Milky Way. They continued to be called nebulae, and it was only gradually that the term galaxies replaced it.

Combining redshifts with distance measurements

[edit]

The velocities and distances that appear in Hubble's law are not directly measured. The velocities are inferred from the redshift z = ∆λ/λ of radiation and distance is inferred from brightness. Hubble sought to correlate brightness with parameter z.

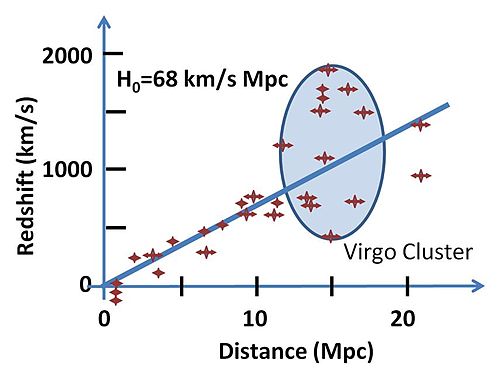

Combining his measurements of galaxy distances with Vesto Slipher and Milton Humason's measurements of the redshifts associated with the galaxies, Hubble discovered a rough proportionality between redshift of an object and its distance. Though there was considerable scatter (now known to be caused by peculiar velocities—the 'Hubble flow' is used to refer to the region of space far enough out that the recession velocity is larger than local peculiar velocities), Hubble was able to plot a trend line from the 46 galaxies he studied and obtain a value for the Hubble constant of 500 (km/s)/Mpc (much higher than the currently accepted value due to errors in his distance calibrations; see cosmic distance ladder for details).[29]

Hubble diagram

[edit]Hubble's law can be easily depicted in a "Hubble diagram" in which the velocity (assumed approximately proportional to the redshift) of an object is plotted with respect to its distance from the observer.[30] A straight line of positive slope on this diagram is the visual depiction of Hubble's law.

Cosmological constant abandoned

[edit]After Hubble's discovery was published, Albert Einstein abandoned his work on the cosmological constant, a term he had inserted into his equations of general relativity to coerce them into producing the static solution he previously considered the correct state of the universe. The Einstein equations in their simplest form model either an expanding or contracting universe, so Einstein introduced the constant to counter expansion or contraction and lead to a static and flat universe.[31] After Hubble's discovery that the universe was, in fact, expanding, Einstein called his faulty assumption that the universe is static his "greatest mistake".[31] On its own, general relativity could predict the expansion of the universe, which (through observations such as the bending of light by large masses, or the precession of the orbit of Mercury) could be experimentally observed and compared to his theoretical calculations using particular solutions of the equations he had originally formulated.

In 1931, Einstein went to Mount Wilson Observatory to thank Hubble for providing the observational basis for modern cosmology.[32]

The cosmological constant has regained attention in recent decades as a hypothetical explanation for dark energy.[33]

Interpretation

[edit]

The discovery of the linear relationship between redshift and distance, coupled with a supposed linear relation between recessional velocity and redshift, yields a straightforward mathematical expression for Hubble's law as follows:

where

- v is the recessional velocity, typically expressed in km/s.

- H0 is Hubble's constant and corresponds to the value of H (often termed the Hubble parameter which is a value that is time dependent and which can be expressed in terms of the scale factor) in the Friedmann equations taken at the time of observation denoted by the subscript 0. This value is the same throughout the universe for a given comoving time.

- D is the proper distance (which can change over time, unlike the comoving distance, which is constant) from the galaxy to the observer, measured in mega parsecs (Mpc), in the 3-space defined by given cosmological time. (Recession velocity is just v = dD/dt).

Hubble's law is considered a fundamental relation between recessional velocity and distance. However, the relation between recessional velocity and redshift depends on the cosmological model adopted and is not established except for small redshifts.

For distances D larger than the radius of the Hubble sphere rHS, objects recede at a rate faster than the speed of light (See Uses of the proper distance for a discussion of the significance of this):

Since the Hubble "constant" is a constant only in space, not in time, the radius of the Hubble sphere may increase or decrease over various time intervals. The subscript '0' indicates the value of the Hubble constant today.[28] Current evidence suggests that the expansion of the universe is accelerating (see Accelerating universe), meaning that for any given galaxy, the recession velocity dD/dt is increasing over time as the galaxy moves to greater and greater distances; however, the Hubble parameter is actually thought to be decreasing with time, meaning that if we were to look at some fixed distance D and watch a series of different galaxies pass that distance, later galaxies would pass that distance at a smaller velocity than earlier ones.[35]

Redshift velocity and recessional velocity

[edit]Redshift can be measured by determining the wavelength of a known transition, such as hydrogen α-lines for distant quasars, and finding the fractional shift compared to a stationary reference. Thus, redshift is a quantity unambiguously acquired from observation. Care is required, however, in translating these to recessional velocities: for small redshift values, a linear relation of redshift to recessional velocity applies, but more generally the redshift-distance law is nonlinear, meaning the co-relation must be derived specifically for each given model and epoch.[36]

Redshift velocity

[edit]The redshift z is often described as a redshift velocity, which is the recessional velocity that would produce the same redshift if it were caused by a linear Doppler effect (which, however, is not the case, as the velocities involved are too large to use a non-relativistic formula for Doppler shift). This redshift velocity can easily exceed the speed of light.[37] In other words, to determine the redshift velocity vrs, the relation:

is used.[38][39] That is, there is no fundamental difference between redshift velocity and redshift: they are rigidly proportional, and not related by any theoretical reasoning. The motivation behind the "redshift velocity" terminology is that the redshift velocity agrees with the velocity from a low-velocity simplification of the so-called Fizeau–Doppler formula[40]

Here, λo, λe are the observed and emitted wavelengths respectively. The "redshift velocity" vrs is not so simply related to real velocity at larger velocities, however, and this terminology leads to confusion if interpreted as a real velocity. Next, the connection between redshift or redshift velocity and recessional velocity is discussed.[41]

Recessional velocity

[edit]Suppose R(t) is called the scale factor of the universe, and increases as the universe expands in a manner that depends upon the cosmological model selected. Its meaning is that all measured proper distances D(t) between co-moving points increase proportionally to R. (The co-moving points are not moving relative to their local environments.) In other words:

where t0 is some reference time.[42] If light is emitted from a galaxy at time te and received by us at t0, it is redshifted due to the expansion of the universe, and this redshift z is simply:

Suppose a galaxy is at distance D, and this distance changes with time at a rate dtD. We call this rate of recession the "recession velocity" vr:

We now define the Hubble constant as

and discover the Hubble law:

From this perspective, Hubble's law is a fundamental relation between (i) the recessional velocity associated with the expansion of the universe and (ii) the distance to an object; the connection between redshift and distance is a crutch used to connect Hubble's law with observations. This law can be related to redshift z approximately by making a Taylor series expansion:

If the distance is not too large, all other complications of the model become small corrections, and the time interval is simply the distance divided by the speed of light:

or

According to this approach, the relation cz = vr is an approximation valid at low redshifts, to be replaced by a relation at large redshifts that is model-dependent. See velocity-redshift figure.

Observability of parameters

[edit]Strictly speaking, neither v nor D in the formula are directly observable, because they are properties now of a galaxy, whereas our observations refer to the galaxy in the past, at the time that the light we currently see left it.

For relatively nearby galaxies (redshift z much less than one), v and D will not have changed much, and v can be estimated using the formula v = zc where c is the speed of light. This gives the empirical relation found by Hubble.

For distant galaxies, v (or D) cannot be calculated from z without specifying a detailed model for how H changes with time. The redshift is not even directly related to the recession velocity at the time the light set out, but it does have a simple interpretation: (1 + z) is the factor by which the universe has expanded while the photon was traveling towards the observer.

Expansion velocity vs. peculiar velocity

[edit]In using Hubble's law to determine distances, only the velocity due to the expansion of the universe can be used. Since gravitationally interacting galaxies move relative to each other independent of the expansion of the universe,[43] these relative velocities, called peculiar velocities, need to be accounted for in the application of Hubble's law. Such peculiar velocities give rise to redshift-space distortions.

Time-dependence of Hubble parameter

[edit]The parameter H is commonly called the "Hubble constant", but that is a misnomer since it is constant in space only at a fixed time; it varies with time in nearly all cosmological models, and all observations of far distant objects are also observations into the distant past, when the "constant" had a different value. "Hubble parameter" is a more correct term, with H0 denoting the present-day value.

Another common source of confusion is that the accelerating universe does not imply that the Hubble parameter is actually increasing with time; since , in most accelerating models increases relatively faster than , so H decreases with time. (The recession velocity of one chosen galaxy does increase, but different galaxies passing a sphere of fixed radius cross the sphere more slowly at later times.)

On defining the dimensionless deceleration parameter , it follows that

From this it is seen that the Hubble parameter is decreasing with time, unless q < -1; the latter can only occur if the universe contains phantom energy, regarded as theoretically somewhat improbable.

However, in the standard Lambda cold dark matter model (Lambda-CDM or ΛCDM model), q will tend to −1 from above in the distant future as the cosmological constant becomes increasingly dominant over matter; this implies that H will approach from above to a constant value of ≈ 57 (km/s)/Mpc, and the scale factor of the universe will then grow exponentially in time.

Idealized Hubble's law

[edit]The mathematical derivation of an idealized Hubble's law for a uniformly expanding universe is a fairly elementary theorem of geometry in 3-dimensional Cartesian/Newtonian coordinate space, which, considered as a metric space, is entirely homogeneous and isotropic (properties do not vary with location or direction). Simply stated, the theorem is this:

Any two points which are moving away from the origin, each along straight lines and with speed proportional to distance from the origin, will be moving away from each other with a speed proportional to their distance apart.

In fact, this applies to non-Cartesian spaces as long as they are locally homogeneous and isotropic, specifically to the negatively and positively curved spaces frequently considered as cosmological models (see shape of the universe).

An observation stemming from this theorem is that seeing objects recede from us on Earth is not an indication that Earth is near to a center from which the expansion is occurring, but rather that every observer in an expanding universe will see objects receding from them.

Ultimate fate and age of the universe

[edit]

A closed universe with ΩM > 1 and ΩΛ = 0 comes to an end in a Big Crunch and is considerably younger than its Hubble age.

An open universe with ΩM ≤ 1 and ΩΛ = 0 expands forever and has an age that is closer to its Hubble age. For the accelerating universe with nonzero ΩΛ that we inhabit, the age of the universe is coincidentally very close to the Hubble age.

The value of the Hubble parameter changes over time, either increasing or decreasing depending on the value of the so-called deceleration parameter q, which is defined by

In a universe with a deceleration parameter equal to zero, it follows that H = 1/t, where t is the time since the Big Bang. A non-zero, time-dependent value of q simply requires integration of the Friedmann equations backwards from the present time to the time when the comoving horizon size was zero.

It was long thought that q was positive, indicating that the expansion is slowing down due to gravitational attraction. This would imply an age of the universe less than 1/H (which is about 14 billion years). For instance, a value for q of 1/2 (once favoured by most theorists) would give the age of the universe as 2/(3H). The discovery in 1998 that q is apparently negative means that the universe could actually be older than 1/H. However, estimates of the age of the universe are very close to 1/H.

Olbers' paradox

[edit]The expansion of space summarized by the Big Bang interpretation of Hubble's law is relevant to the old conundrum known as Olbers' paradox: If the universe were infinite in size, static, and filled with a uniform distribution of stars, then every line of sight in the sky would end on a star, and the sky would be as bright as the surface of a star. However, the night sky is largely dark.[44][45]

Since the 17th century, astronomers and other thinkers have proposed many possible ways to resolve this paradox, but the currently accepted resolution depends in part on the Big Bang theory, and in part on the Hubble expansion: in a universe that existed for a finite amount of time, only the light of a finite number of stars has had enough time to reach us, and the paradox is resolved. Additionally, in an expanding universe, distant objects recede from us, which causes the light emanated from them to be redshifted and diminished in brightness by the time we see it.[44][45]

Dimensionless Hubble constant

[edit]Instead of working with Hubble's constant, a common practice is to introduce the dimensionless Hubble constant, usually denoted by h and commonly referred to as "little h",[29] then to write Hubble's constant H0 as h × 100 km⋅s−1⋅Mpc−1, all the relative uncertainty of the true value of H0 being then relegated to h.[46] The dimensionless Hubble constant is often used when giving distances that are calculated from redshift z using the formula d ≈ c/H0 × z. Since H0 is not precisely known, the distance is expressed as:

In other words, one calculates 2998 × z and one gives the units as Mpc h-1 or h-1 Mpc.

Occasionally a reference value other than 100 may be chosen, in which case a subscript is presented after h to avoid confusion; e.g. h70 denotes H0 = 70 h70 (km/s)/Mpc, which implies h70 = h / 0.7.

This should not be confused with the dimensionless value of Hubble's constant, usually expressed in terms of Planck units, obtained by multiplying H0 by 1.75×10−63 (from definitions of parsec and tP), for example for H0 = 70, a Planck unit version of 1.2×10−61 is obtained.

Acceleration of the expansion

[edit]A value for q measured from standard candle observations of Type Ia supernovae, which was determined in 1998 to be negative, surprised many astronomers with the implication that the expansion of the universe is currently "accelerating"[47] (although the Hubble factor is still decreasing with time, as mentioned above in the Interpretation section; see the articles on dark energy and the ΛCDM model).

Derivation of the Hubble parameter

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2014) |

Start with the Friedmann equation:

where H is the Hubble parameter, a is the scale factor, G is the gravitational constant, k is the normalised spatial curvature of the universe and equal to −1, 0, or 1, and Λ is the cosmological constant.

Matter-dominated universe (with a cosmological constant)

[edit]If the universe is matter-dominated, then the mass density of the universe ρ should be taken to include just matter so

where ρm0 is the density of matter today. From the Friedmann equation and thermodynamic principles we know for non-relativistic particles that their mass density decreases proportional to the inverse volume of the universe, so the equation above must be true. We can also define (see density parameter for Ωm)

therefore:

Also, by definition,

where the subscript 0 refers to the values today, and a0 = 1. Substituting all of this into the Friedmann equation at the start of this section and replacing a with a = 1/(1+z) gives

Matter- and dark energy-dominated universe

[edit]If the universe is both matter-dominated and dark energy-dominated, then the above equation for the Hubble parameter will also be a function of the equation of state of dark energy. So now:

where ρde is the mass density of the dark energy. By definition, an equation of state in cosmology is P = wρc2, and if this is substituted into the fluid equation, which describes how the mass density of the universe evolves with time, then

If w is constant, then

implying:

Therefore, for dark energy with a constant equation of state w, . If this is substituted into the Friedman equation in a similar way as before, but this time set k = 0, which assumes a spatially flat universe, then (see shape of the universe)

If the dark energy derives from a cosmological constant such as that introduced by Einstein, it can be shown that w = −1. The equation then reduces to the last equation in the matter-dominated universe section, with Ωk set to zero. In that case the initial dark energy density ρde0 is given by[48]

If dark energy does not have a constant equation-of-state w, then

and to solve this, w(a) must be parametrized, for example if w(a) = w0 + wa(1−a), giving[49]

Units derived from the Hubble constant

[edit]Hubble time

[edit]The Hubble constant H0 has units of inverse time; the Hubble time tH is simply defined as the inverse of the Hubble constant,[50] i.e.

This is slightly different from the age of the universe, which is approximately 13.8 billion years. The Hubble time is the age it would have had if the expansion had been linear,[51] and it is different from the real age of the universe because the expansion is not linear; it depends on the energy content of the universe (see § Derivation of the Hubble parameter).

We currently appear to be approaching a period where the expansion of the universe is exponential due to the increasing dominance of vacuum energy. In this regime, the Hubble parameter is constant, and the universe grows by a factor e each Hubble time:

Likewise, the generally accepted value of 2.27 Es−1 means that (at the current rate) the universe would grow by a factor of e2.27 in one exasecond.

Over long periods of time, the dynamics are complicated by general relativity, dark energy, inflation, etc., as explained above.

Hubble length

[edit]The Hubble length or Hubble distance is a unit of distance in cosmology, defined as cH−1 — the speed of light multiplied by the Hubble time. It is equivalent to 4,420 million parsecs or 14.4 billion light years. (The numerical value of the Hubble length in light years is, by definition, equal to that of the Hubble time in years.) Substituting D = cH−1 into the equation for Hubble's law, v = H0D reveals that the Hubble distance specifies the distance from our location to those galaxies which are currently receding from us at the speed of light.

Hubble volume

[edit]The Hubble volume is sometimes defined as a volume of the universe with a comoving size of cH−1. The exact definition varies: it is sometimes defined as the volume of a sphere with radius cH−1, or alternatively, a cube of side cH−1. Some cosmologists even use the term Hubble volume to refer to the volume of the observable universe, although this has a radius approximately three times larger.

Determining the Hubble constant

[edit]

The value of the Hubble constant, H0, cannot be measured directly, but is derived from a combination of astronomical observations and model-dependent assumptions. Increasingly accurate observations and new models over many decades have led to two sets of highly precise values which do not agree. This difference is known as the "Hubble tension".[8][53]

Earlier measurements

[edit]For the original 1929 estimate of the constant now bearing his name, Hubble used observations of Cepheid variable stars as "standard candles" to measure distance.[54] The result he obtained was 500 (km/s)/Mpc, much larger than the value astronomers currently calculate. Later observations by astronomer Walter Baade led him to realize that there were distinct "populations" for stars (Population I and Population II) in a galaxy. The same observations led him to discover that there are two types of Cepheid variable stars with different luminosities. Using this discovery, he recalculated Hubble constant and the size of the known universe, doubling the previous calculation made by Hubble in 1929.[55][56][54] He announced this finding to considerable astonishment at the 1952 meeting of the International Astronomical Union in Rome.

For most of the second half of the 20th century, the value of H0 was estimated to be between 50 and 90 (km/s)/Mpc.

The value of the Hubble constant was the topic of a long and rather bitter controversy between Gérard de Vaucouleurs, who claimed the value was around 100, and Allan Sandage, who claimed the value was near 50.[57] In one demonstration of vitriol between the parties, when Sandage and his colleague Gustav Andreas Tammann formally acknowledged the shortcomings of confirming the systematic error of their method in 1975, Vaucouleurs responded: "It is unfortunate that this sober warning was so soon forgotten and ignored by most astronomers and textbook writers".[58] In 1996, a debate moderated by John Bahcall between Sidney van den Bergh and Gustav Tammann was held in similar fashion to the earlier Shapley–Curtis debate over these two competing values.

This previously wide variance in estimates was partially resolved with the introduction of the ΛCDM model of the universe in the late 1990s. Incorporating the ΛCDM model, observations of high-redshift clusters at X-ray and microwave wavelengths using the Sunyaev–Zel'dovich effect, measurements of anisotropies in the cosmic microwave background radiation, and optical surveys all gave a value of around 50–70 km/s/Mpc for the constant.[59]

Precision cosmology and the Hubble tension

[edit]By the late 1990s, advances in ideas and technology allowed higher precision measurements.[60] However, two major categories of methods, each with high precision, fail to agree. "Late universe" measurements using calibrated distance ladder techniques have converged on a value of approximately 73 (km/s)/Mpc. Since 2000, "early universe" techniques based on measurements of the cosmic microwave background have become available, and these agree on a value near 67.7 (km/s)/Mpc.[61] (This accounts for the change in the expansion rate since the early universe, so is comparable to the first number.) Initially, this discrepancy was within the estimated measurement uncertainties and thus no cause for concern. However, as techniques have improved, the estimated measurement uncertainties have shrunk, but the discrepancies have not, to the point that the disagreement is now highly statistically significant. This discrepancy is called the Hubble tension.[62][63]

An example of an "early" measurement, the Planck mission published in 2018 gives a value for H0 = of 67.4±0.5 (km/s)/Mpc.[64] In the "late" camp is the higher value of 74.03±1.42 (km/s)/Mpc determined by the Hubble Space Telescope[65] and confirmed by the James Webb Space Telescope in 2023.[66][67] The "early" and "late" measurements disagree at the >5 σ level, beyond a plausible level of chance.[68][69] The resolution to this disagreement is an ongoing area of active research.[70]

Reducing systematic errors

[edit]Since 2013, extensive checks for possible systematic errors and improvements in reproducibility have been undertaken.[53]

The "late universe" or distance ladder measurements typically employ three stages or "rungs". In the first rung, distances to Cepheids are determined while trying to reduce luminosity errors from dust and correlations of metallicity with luminosity. The second rung uses Type Ia supernova, explosions of almost constant amounts of mass. Thusly, these produce very similar amounts of light; the primary systematic error in this case is the limited number of objects that can be observed. The third rung of the distance ladder measures the red-shift of supernovae to extract the Hubble flow, and from that the constant. At this rung, corrections due to motion other than expansion are applied.[53]: 2.1 As an example of the kind of work needed to reduce systematic errors, photometry on observations from the James Webb Space Telescope of extra-galactic Cepheids confirm the findings from the HST. The higher resolution avoided confusion from crowding of stars in the field of view but came to the same value for H0.[71][53]

The "early universe" or inverse distance ladder measures the observable consequences of spherical sound waves on primordial plasma density. These pressure waves – called baryon acoustic oscillations (BAO) – ceased once the universe cooled enough for electrons to stay bound to nuclei, ending the plasma and allowing the photons trapped by interaction with the plasma to escape. The subsequent pressure waves are evident in very small perturbations in the density imprinted on the cosmic microwave background, and on the large-scale density of galaxies across the sky. Detailed structure in high-precision measurements of the CMB can be matched to physics models of the oscillations. These models depend upon the Hubble constant such that a match reveals a value for the constant. Similarly, the BAO affects the statistical distribution of matter, observed as distant galaxies across the sky.

These two independent measurements produce similar values for the constant from the current models, giving strong evidence that systematic errors in the measurements themselves do not affect the result.[53]: Sup. B

Other kinds of measurements

[edit]In addition to measurements based on calibrated distance ladder techniques or measurements of the CMB, other methods have been used to determine the Hubble constant.

One alternative method for constraining the Hubble constant involves transient events seen in multiple images of a strongly lensed object. A transient event, such as a supernova, is seen at different times in each of the lensed images, and if this time delay between each image can be measured, it can be used to constrain the Hubble constant. This method is commonly known as "time-delay cosmography", and was first proposed by Refsdal in 1964,[72] years before the first strongly lensed object was observed. The first strongly lensed supernova to be discovered was named SN Refsdal in his honor. While Refsdal suggested this could be done with supernovae, he also noted that extremely luminous and distant star-like objects could also be used. These objects were later named quasars, and to date (April 2025) the majority of time-delay cosmography measurements have been done with strongly lensed quasars. This is because current samples of lensed quasars vastly outnumber known lensed supernovae, of which <10 are known. This is expected to change dramatically in the next few years, with surveys such as LSST expected to discover ~10 lensed SNe in the first three years of observation.[73] For example time-delay constraints on H0, see the results from STRIDES and H0LiCOW in the table below.

In October 2018, scientists used information from gravitational wave events (especially those involving the merger of neutron stars, like GW170817), of determining the Hubble constant.[74][75]

In July 2019, astronomers reported that a new method to determine the Hubble constant, and resolve the discrepancy of earlier methods, has been proposed based on the mergers of pairs of neutron stars, following the detection of the neutron star merger of GW170817, an event known as a dark siren.[76][77] Their measurement of the Hubble constant is 73.3+5.3

−5.0 (km/s)/Mpc.[78]

Also in July 2019, astronomers reported another new method, using data from the Hubble Space Telescope and based on distances to red giant stars calculated using the tip of the red-giant branch (TRGB) distance indicator. Their measurement of the Hubble constant is 69.8+1.9

−1.9 (km/s)/Mpc.[79][80][81]

In February 2020, the Megamaser Cosmology Project published independent results based on astrophysical masers visible at cosmological distances and which do not require multi-step calibration. That work confirmed the distance ladder results and differed from the early-universe results at a statistical significance level of 95%.[82]

In July 2020, measurements of the cosmic background radiation by the Atacama Cosmology Telescope predict that the Universe should be expanding more slowly than is currently observed.[83]

In July 2023, an independent estimate of the Hubble constant was derived from a kilonova, the optical afterglow of a neutron star merger, using the expanding photosphere method.[84] Due to the blackbody nature of early kilonova spectra,[85] such systems provide strongly constraining estimators of cosmic distance. Using the kilonova AT2017gfo (the aftermath of, once again, GW170817), these measurements indicate a local-estimate of the Hubble constant of 67.0±3.6 (km/s)/Mpc.[86][84]

Possible resolutions of the Hubble tension

[edit]The cause of the Hubble tension is unknown,[87] and there are many possible proposed solutions. The most conservative is that there is an unknown systematic error affecting either early-universe or late-universe observations. Although intuitively appealing, this explanation requires multiple unrelated effects regardless of whether early-universe or late-universe observations are incorrect, and there are no obvious candidates. Furthermore, any such systematic error would need to affect multiple different instruments, since both the early-universe and late-universe observations come from several different telescopes.[53]

Alternatively, it could be that the observations are correct, but some unaccounted-for effect is causing the discrepancy. If the cosmological principle fails (see Lambda-CDM model § Violations of the cosmological principle), then the existing interpretations of the Hubble constant and the Hubble tension have to be revised, which might resolve the Hubble tension.[88] In particular, we would need to be located within a very large void, up to about a redshift of 0.5, for such an explanation to conflate with supernovae and baryon acoustic oscillation observations.[63] Yet another possibility is that the uncertainties in the measurements could have been underestimated, but given the internal agreements this is neither likely, nor resolves the overall tension.[53]

Finally, another possibility is new physics beyond the currently accepted cosmological model of the universe, the ΛCDM model.[63][89] There are very many theories in this category, for example, replacing general relativity with a modified theory of gravity could potentially resolve the tension,[90][91] as can a dark energy component in the early universe,[b][92] dark energy with a time-varying equation of state,[c][93] or dark matter that decays into dark radiation.[94] A problem faced by all these theories is that both early-universe and late-universe measurements rely on multiple independent lines of physics, and it is difficult to modify any of those lines while preserving their successes elsewhere. The scale of the challenge can be seen from how some authors have argued that new early-universe physics alone is not sufficient;[95][96] while other authors argue that new late-universe physics alone is also not sufficient.[97] Nonetheless, astronomers are trying, with interest in the Hubble tension growing strongly since the mid 2010s.[63]

Measurements of the Hubble constant

[edit]| Date published | Hubble constant (km/s)/Mpc |

Observer | Citation | Remarks / methodology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2025-05-27 | 70.39±1.94 | W. Freedman et al | [98] | Tip of the Red Giant Branch (TRGB) method (values from J-Region Asymptotic Giant Branch (JAGB) and Cepheids also reported)(JWST and HST data)[99] |

| 2025-01-14 | 75.7+8.1 −5.5 |

Pascale et al. | [100] | Timing delay of gravitationally lensed images of Supernova H0pe. Independent of cosmic distance ladder or the CMB. JWST data. (2023-05-11 cell and this one are the only 2 values with this method so far) |

| 2024-12-01 | 72.6±2.0 | SH0ES+CCHP JWST | [101] | JWST, 3 methods, Cepheids, TRGB, JAGB, 2 groups data |

| 2023-07-19 | 67.0±3.6 | Sneppen et al. | [86][84] | Due to the blackbody spectra of the optical counterpart of neutron-star mergers, these systems provide strongly constraining estimators of cosmic distance. |

| 2023-07-13 | 68.3±1.5 | SPT-3G | [102] | CMB TT/TE/EE power spectrum. Less than 1σ discrepancy with Planck. |

| 2023-05-11 | 66.6+4.1 −3.3 |

P. L. Kelly et al. | [103] | Timing delay of gravitationally lensed images of Supernova Refsdal. Independent of cosmic distance ladder or the CMB. |

| 2022-12-14 | 67.3+10.0 −9.1 |

S. Contarini et al. | [104] | Statistics of cosmic voids using BOSS DR12 data set.[105] |

| 2022-02-08 | 73.4+0.99 −1.22 |

Pantheon+ | [106] | SN Ia distance ladder (+SH0ES) |

| 2022-06-17 | 75.4+3.8 −3.7 |

T. de Jaeger et al. | [107] | Use Type II supernovae as standardisable candles to obtain an independent measurement of the Hubble constant—13 SNe II with host-galaxy distances measured from Cepheid variables, the tip of the red giant branch, and geometric distance (NGC 4258). |

| 2021-12-08 | 73.04±1.04 | SH0ES | [108] | Cepheids-SN Ia distance ladder (HST+Gaia EDR3+"Pantheon+"). 5σ discrepancy with planck. |

| 2021-09-17 | 69.8±1.7 | W. Freedman | [109] | Tip of the red-giant branch (TRGB) distance indicator (HST+Gaia EDR3) |

| 2020-12-16 | 72.1±2.0 | Hubble Space Telescope and Gaia EDR3 | [110] | Combining earlier work on red giant stars, using the tip of the red-giant branch (TRGB) distance indicator, with parallax measurements of Omega Centauri from Gaia EDR3. |

| 2020-12-15 | 73.2±1.3 | Hubble Space Telescope and Gaia EDR3 | [111] | Combination of HST photometry and Gaia EDR3 parallaxes for Milky Way Cepheids, reducing the uncertainty in calibration of Cepheid luminosities to 1.0%. Overall uncertainty in the value for H0 is 1.8%, which is expected to be reduced to 1.3% with a larger sample of type Ia supernovae in galaxies that are known Cepheid hosts. Continuation of a collaboration known as Supernovae, H0, for the Equation of State of Dark Energy (SHoES). |

| 2020-12-04 | 73.5±5.3 | E. J. Baxter, B. D. Sherwin | [112] | Gravitational lensing in the CMB is used to estimate H0 without referring to the sound horizon scale, providing an alternative method to analyze the Planck data. |

| 2020-11-25 | 71.8+3.9 −3.3 |

P. Denzel et al. | [113] | Eight quadruply lensed galaxy systems are used to determine H0 to a precision of 5%, in agreement with both "early" and "late" universe estimates. Independent of distance ladders and the cosmic microwave background. |

| 2020-11-07 | 67.4±1.0 | T. Sedgwick et al. | [114] | Derived from 88 0.02 < z < 0.05 Type Ia supernovae used as standard candle distance indicators. The H0 estimate is corrected for the effects of peculiar velocities in the supernova environments, as estimated from the galaxy density field. The result assumes Ωm = 0.3, ΩΛ = 0.7 and a sound horizon of 149.3 Mpc, a value taken from Anderson et al. (2014).[115] |

| 2020-09-29 | 67.6+4.3 −4.2 |

S. Mukherjee et al. | [116] | Gravitational waves, assuming that the transient ZTF19abanrh found by the Zwicky Transient Facility is the optical counterpart to GW190521. Independent of distance ladders and the cosmic microwave background. |

| 2020-06-18 | 75.8+5.2 −4.9 |

T. de Jaeger et al. | [117] | Use Type II supernovae as standardisable candles to obtain an independent measurement of the Hubble constant—7 SNe II with host-galaxy distances measured from Cepheid variables or the tip of the red giant branch. |

| 2020-02-26 | 73.9±3.0 | Megamaser Cosmology Project | [82] | Geometric distance measurements to megamaser-hosting galaxies. Independent of distance ladders and the cosmic microwave background. |

| 2019-10-14 | 74.2+2.7 −3.0 |

STRIDES | [118] | Modelling the mass distribution & time delay of the lensed quasar DES J0408-5354. |

| 2019-09-12 | 76.8±2.6 | SHARP/H0LiCOW | [119] | Modelling three galactically lensed objects and their lenses using ground-based adaptive optics and the Hubble Space Telescope. |

| 2019-08-20 | 73.3+1.36 −1.35 |

K. Dutta et al. | [120] | This is obtained analysing low-redshift cosmological data within ΛCDM model. The datasets used are type-Ia supernovae, baryon acoustic oscillations, time-delay measurements using strong-lensing, H(z) measurements using cosmic chronometers and growth measurements from large scale structure observations. |

| 2019-08-15 | 73.5±1.4 | M. J. Reid, D. W. Pesce, A. G. Riess | [121] | Measuring the distance to Messier 106 using its supermassive black hole, combined with measurements of eclipsing binaries in the Large Magellanic Cloud. |

| 2019-07-16 | 69.8±1.9 | Hubble Space Telescope | [79][80][81] | Distances to red giant stars are calculated using the tip of the red-giant branch (TRGB) distance indicator. |

| 2019-07-10 | 73.3+1.7 −1.8 |

H0LiCOW collaboration | [122] | Updated observations of multiply imaged quasars, now using six quasars, independent of the cosmic distance ladder and independent of the cosmic microwave background measurements. |

| 2019-07-08 | 70.3+5.3 −5.0 |

The LIGO Scientific Collaboration and The Virgo Collaboration | [78] | Uses radio counterpart of GW170817, combined with earlier gravitational wave (GW) and electromagnetic (EM) data. |

| 2019-03-28 | 68.0+4.2 −4.1 |

Fermi-LAT | [123] | Gamma ray attenuation due to extragalactic light. Independent of the cosmic distance ladder and the cosmic microwave background. |

| 2019-03-18 | 74.03±1.42 | Hubble Space Telescope | [68] | Precision HST photometry of Cepheids in the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC) reduce the uncertainty in the distance to the LMC from 2.5% to 1.3%. The revision increases the tension with CMB measurements to the 4.4σ level (P=99.999% for Gaussian errors), raising the discrepancy beyond a plausible level of chance. Continuation of a collaboration known as Supernovae, H0, for the Equation of State of Dark Energy (SHoES). |

| 2019-02-08 | 67.78+0.91 −0.87 |

Joseph Ryan et al. | [124] | Quasar angular size and baryon acoustic oscillations, assuming a flat ΛCDM model. Alternative models result in different (generally lower) values for the Hubble constant. |

| 2018-11-06 | 67.77±1.30 | Dark Energy Survey | [125] | Supernova measurements using the inverse distance ladder method based on baryon acoustic oscillations. |

| 2018-09-05 | 72.5+2.1 −2.3 |

H0LiCOW collaboration | [126] | Observations of multiply imaged quasars, independent of the cosmic distance ladder and independent of the cosmic microwave background measurements. |

| 2018-07-18 | 67.66±0.42 | Planck Mission | [64] | Final Planck 2018 results. |

| 2018-04-27 | 73.52±1.62 | Hubble Space Telescope and Gaia | [127][128] | Additional HST photometry of galactic Cepheids with early Gaia parallax measurements. The revised value increases tension with CMB measurements at the 3.8σ level. Continuation of the SHoES collaboration. |

| 2018-02-22 | 73.45±1.66 | Hubble Space Telescope | [129][130] | Parallax measurements of galactic Cepheids for enhanced calibration of the distance ladder; the value suggests a discrepancy with CMB measurements at the 3.7σ level. The uncertainty is expected to be reduced to below 1% with the final release of the Gaia catalog. SHoES collaboration. |

| 2017-10-16 | 70.0+12.0 −8.0 |

The LIGO Scientific Collaboration and The Virgo Collaboration | [131] | Standard siren measurement independent of normal "standard candle" techniques; the gravitational wave analysis of a binary neutron star (BNS) merger GW170817 directly estimated the luminosity distance out to cosmological scales. An estimate of fifty similar detections in the next decade may arbitrate tension of other methodologies.[132] Detection and analysis of a neutron star-black hole merger (NSBH) may provide greater precision than BNS could allow.[133] |

| 2016-11-22 | 71.9+2.4 −3.0 |

Hubble Space Telescope | [134] | Uses time delays between multiple images of distant variable sources produced by strong gravitational lensing. Collaboration known as H0 Lenses in COSMOGRAIL's Wellspring (H0LiCOW). |

| 2016-08-04 | 76.2+3.4 −2.7 |

Cosmicflows-3 | [135] | Comparing redshift to other distance methods, including Tully–Fisher, Cepheid variable, and Type Ia supernovae. A restrictive estimate from the data implies a more precise value of 75±2. |

| 2016-07-13 | 67.6+0.7 −0.6 |

SDSS-III Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey (BOSS) | [136] | Baryon acoustic oscillations. An extended survey (eBOSS) began in 2014 and is expected to run through 2020. The extended survey is designed to explore the time when the universe was transitioning away from the deceleration effects of gravity from 3 to 8 billion years after the Big Bang.[137] |

| 2016-05-17 | 73.24±1.74 | Hubble Space Telescope | [138] | Type Ia supernova, the uncertainty is expected to go down by a factor of more than two with upcoming Gaia measurements and other improvements. SHoES collaboration. |

| 2015-02 | 67.74±0.46 | Planck Mission | [139][140] | Results from an analysis of Planck's full mission were made public on 1 December 2014 at a conference in Ferrara, Italy. A full set of papers detailing the mission results were released in February 2015. |

| 2013-10-01 | 74.4±3.0 | Cosmicflows-2 | [141] | Comparing redshift to other distance methods, including Tully–Fisher, Cepheid variable, and Type Ia supernovae. |

| 2013-03-21 | 67.80±0.77 | Planck Mission | [52][142][143][144][145] | The ESA Planck Surveyor was launched in May 2009. Over a four-year period, it performed a significantly more detailed investigation of cosmic microwave radiation than earlier investigations using HEMT radiometers and bolometer technology to measure the CMB at a smaller scale than WMAP. On 21 March 2013, the European-led research team behind the Planck cosmology probe released the mission's data including a new CMB all-sky map and their determination of the Hubble constant. |

| 2012-12-20 | 69.32±0.80 | WMAP (9 years), combined with other measurements | [146] | |

| 2010 | 70.4+1.3 −1.4 |

WMAP (7 years), combined with other measurements | [147] | These values arise from fitting a combination of WMAP and other cosmological data to the simplest version of the ΛCDM model. If the data are fit with more general versions, H0 tends to be smaller and more uncertain: typically around 67±4 (km/s)/Mpc although some models allow values near 63 (km/s)/Mpc.[148] |

| 2010 | 71.0±2.5 | WMAP only (7 years). | [147] | |

| 2009-02 | 70.5±1.3 | WMAP (5 years), combined with other measurements | [149] | |

| 2009-02 | 71.9+2.6 −2.7 |

WMAP only (5 years) | [149] | |

| 2007 | 70.4+1.5 −1.6 |

WMAP (3 years), combined with other measurements | [150] | |

| 2006-08 | 76.9+10.7 −8.7 |

Chandra X-ray Observatory | [151] | Combined Sunyaev–Zeldovich effect and Chandra X-ray observations of galaxy clusters. Adjusted uncertainty in table from Planck Collaboration 2013.[152] |

| 2003 | 72±5 | WMAP (First year) only | [153] | |

| 2001-05 | 72±8 | Hubble Space Telescope Key Project | [154] | This project established the most precise optical determination, consistent with a measurement of H0 based upon Sunyaev–Zel'dovich effect observations of many galaxy clusters having a similar accuracy. |

| before 1996 | 50 — 90 (est.) | [57] | ||

| 1994 | 67±7 | Supernova 1a Light Curve Shapes | [155] | Determined relationship between luminosity of SN 1a's and their Light Curve Shapes. Riess et al. used this ratio of the light curve of SN 1972E and the Cepheid distance to NGC 5253 to determine the constant. |

| mid 1970's | 100±10 | Gérard de Vaucouleurs | [58] | De Vaucouleurs believed he had improved the accuracy of Hubble's constant from Sandage's because he used 5x more primary indicators, 10× more calibration methods, 2× more secondary indicators, and 3× as many galaxy data points to derive his 100±10. |

| early 1970s | 55 (est.) | Allan Sandage and Gustav Tammann | [156] | |

| 1958 | 75 (est.) | Allan Sandage | [157] | This was the first good estimate of H0, but it would be decades before a consensus was achieved. |

| 1956 | 180 | Humason, Mayall and Sandage | [156] | |

| 1929 | 500 | Edwin Hubble, Hooker telescope | [158][156][159] | |

| 1927 | 625 | Georges Lemaître | [160] | First measurement and interpretation as a sign of the expansion of the universe. |

See also

[edit]- List of scientists whose names are used in physical constants

- S8 tension- a similar problem from another parameter of the ΛCDM model.

- Tests of general relativity

Notes

[edit]- ^ See Comoving and proper distances § Uses of the proper distance for discussion of the subtleties of this definition of velocity.

- ^ In standard ΛCDM, dark energy only comes into play in the late universe – its effect in the early universe is too small to have an effect.

- ^ In standard ΛCDM, dark energy has a constant equation of state w = −1.

References

[edit]- ^ "IAU members vote to recommend renaming the Hubble law as the Hubble–Lemaître law" (Press release). IAU. 29 October 2018. Archived from the original on 2019-03-30. Retrieved 2018-10-29.

- ^ van den Bergh, S. (August 2011). "The Curious Case of Lemaitre's Equation No. 24". Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. 105 (4): 151. arXiv:1106.1195. Bibcode:2011JRASC.105..151V.

- ^ Nussbaumer, H.; Bieri, L. (2011). "Who discovered the expanding universe?". The Observatory. 131 (6): 394–398. arXiv:1107.2281. Bibcode:2011Obs...131..394N.

- ^ Way, M.J. (2013). "Dismantling Hubble's Legacy?" (PDF). In Michael J. Way; Deidre Hunter (eds.). Origins of the Expanding Universe: 1912-1932. ASP Conference Series. Vol. 471. Astronomical Society of the Pacific. pp. 97–132. arXiv:1301.7294. Bibcode:2013ASPC..471...97W.

- ^ Friedman, A. (December 1922). "Über die Krümmung des Raumes". Zeitschrift für Physik (in German). 10 (1): 377–386. Bibcode:1922ZPhy...10..377F. doi:10.1007/BF01332580. S2CID 125190902.. (English translation in Friedman, A. (December 1999). "On the Curvature of Space". General Relativity and Gravitation. 31 (12): 1991–2000. Bibcode:1999GReGr..31.1991F. doi:10.1023/A:1026751225741. S2CID 122950995.)

- ^ Wirtz, C. W. (April 1922). "Einiges zur Statistik der Radialbewegungen von Spiralnebeln und Kugelsternhaufen". Astronomische Nachrichten. 215 (17): 349–354. Bibcode:1922AN....215..349W. doi:10.1002/asna.19212151703.

- ^ Wirtz, C. W. (1924). "De Sitters Kosmologie und die Radialbewegungen der Spiralnebel". Astronomische Nachrichten. 222 (5306): 21–26. Bibcode:1924AN....222...21W. doi:10.1002/asna.19242220203.

- ^ a b c Overbye, Dennis (20 February 2017). "Cosmos Controversy: The Universe Is Expanding, but How Fast?". New York Times. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ^ Lemaître, G. (1927). "Un univers homogène de masse constante et de rayon croissant rendant compte de la vitesse radiale des nébuleuses extra-galactiques". Annales de la Société Scientifique de Bruxelles A (in French). 47: 49–59. Bibcode:1927ASSB...47...49L. Partially translated to English in Lemaître, G. (1931). "Expansion of the universe, A homogeneous universe of constant mass and increasing radius accounting for the radial velocity of extra-galactic nebulae". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 91 (5): 483–490. Bibcode:1931MNRAS..91..483L. doi:10.1093/mnras/91.5.483.

- ^ a b Livio, M. (2011). "Lost in translation: Mystery of the missing text solved". Nature. 479 (7372): 171–173. Bibcode:2011Natur.479..171L. doi:10.1038/479171a. PMID 22071745. S2CID 203468083.

- ^ Livio, M.; Riess, A. (2013). "Measuring the Hubble constant". Physics Today. 66 (10): 41–47. Bibcode:2013PhT....66j..41L. doi:10.1063/PT.3.2148.

- ^ Hubble, E. (1929). "A relation between distance and radial velocity among extra-galactic nebulae". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 15 (3): 168–173. Bibcode:1929PNAS...15..168H. doi:10.1073/pnas.15.3.168. PMC 522427. PMID 16577160.

- ^ Slipher, V.M. (1917). "Radial velocity observations of spiral nebulae". The Observatory. 40: 304–306. Bibcode:1917Obs....40..304S.

- ^ Longair, M. S. (2006). The Cosmic Century. Cambridge University Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-521-47436-8.

- ^ Nussbaumer, Harry (2013). "Slipher's redshifts as support for de Sitter's model and the discovery of the dynamic universe" (PDF). In Michael J. Way; Deidre Hunter (eds.). Origins of the Expanding Universe: 1912–1932. ASP Conference Series. Vol. 471. Astronomical Society of the Pacific. pp. 25–38. arXiv:1303.1814.

- ^ "1912: Henrietta Leavitt Discovers the Distance Key". Everyday Cosmology. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- ^ Coles, P., ed. (2001). Routledge Critical Dictionary of the New Cosmology. Routledge. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-203-16457-0.

- ^ "Hubble Flow". The Swinburne Astronomy Online Encyclopedia of Astronomy. Swinburne University of Technology. Retrieved 2013-05-14.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (25 February 2019). "Have Dark Forces Been Messing With the Cosmos? – Axions? Phantom energy? Astrophysicists scramble to patch a hole in the universe, rewriting cosmic history in the process". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ^ O'Raifeartaigh, Cormac (2013). "The Contribution of V.M. Slipher to the discovery of the expanding universe" (PDF). Origins of the Expanding Universe: 1912-1932. ASP Conference Series. Vol. 471. Astronomical Society of the Pacific. pp. 49–62. arXiv:1212.5499.

- ^ "Three steps to the Hubble constant". www.spacetelescope.org. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- ^ Slipher, V. M. (1913). "The Radial Velocity of the Andromeda Nebula". Lowell Observatory Bulletin. 1 (8): 56–57. Bibcode:1913LowOB...2...56S.

- ^ Slipher, V. M. (1915). "Spectrographic Observations of Nebulae". Popular Astronomy. 23: 21–24. Bibcode:1915PA.....23...21S.

- ^ Friedman, A. (1922). "Über die Krümmung des Raumes". Zeitschrift für Physik (in German). 10 (1): 377–386. Bibcode:1922ZPhy...10..377F. doi:10.1007/BF01332580. S2CID 125190902. Translated to English in Friedmann, A. (1999). "On the Curvature of Space". General Relativity and Gravitation. 31 (12): 1991–2000. Bibcode:1999GReGr..31.1991F. doi:10.1023/A:1026751225741. S2CID 122950995.

- ^ van den Bergh, Sydney (2011). "The Curious Case of Lemaître's Equation No. 24". Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. 105 (4): 151. arXiv:1106.1195. Bibcode:2011JRASC.105..151V.

- ^ Block, David (2012). 'Georges Lemaitre and Stigler's law of eponymy' in Georges Lemaître: Life, Science and Legacy (Holder and Mitton ed.). Springer. pp. 89–96.

- ^ Sandage, Allan (December 1989). "Edwin Hubble 1889–1953". Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. 83 (6): 351–362. Bibcode:1989JRASC..83..351S.

- ^ a b Keel, W. C. (2007). The Road to Galaxy Formation (2nd ed.). Springer. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-3-540-72534-3.

- ^ a b Croton, Darren J. (14 October 2013). "Damn You, Little h! (Or, Real-World Applications of the Hubble Constant Using Observed and Simulated Data)". Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia. 30 e052. arXiv:1308.4150. Bibcode:2013PASA...30...52C. doi:10.1017/pasa.2013.31. S2CID 119257465. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ Kirshner, R. P. (2003). "Hubble's diagram and cosmic expansion". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 101 (1): 8–13. Bibcode:2004PNAS..101....8K. doi:10.1073/pnas.2536799100. PMC 314128. PMID 14695886.

- ^ a b "What is a Cosmological Constant?". Goddard Space Flight Center. Retrieved 2013-10-17.

- ^ Isaacson, W. (2007). Einstein: His Life and Universe. Simon & Schuster. p. 354. ISBN 978-0-7432-6473-0.

- ^ "Einstein's Biggest Blunder? Dark Energy May Be Consistent With Cosmological Constant". Science Daily. 28 November 2007. Retrieved 2013-06-02.

- ^ Davis, T. M.; Lineweaver, C. H. (2001). "Superluminal Recessional Velocities". AIP Conference Proceedings. 555: 348–351. arXiv:astro-ph/0011070. Bibcode:2001AIPC..555..348D. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.254.1810. doi:10.1063/1.1363540. S2CID 118876362.

- ^ "Is the universe expanding faster than the speed of light?". Ask an Astronomer at Cornell University. Archived from the original on 23 November 2003. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ^ Harrison, E. (1992). "The redshift-distance and velocity-distance laws". The Astrophysical Journal. 403: 28–31. Bibcode:1993ApJ...403...28H. doi:10.1086/172179.

- ^ Madsen, M. S. (1995). The Dynamic Cosmos. CRC Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-412-62300-4.

- ^ Dekel, A.; Ostriker, J. P. (1999). Formation of Structure in the Universe. Cambridge University Press. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-521-58632-0.

- ^ Padmanabhan, T. (1993). Structure formation in the universe. Cambridge University Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-521-42486-8.

- ^ Sartori, L. (1996). Understanding Relativity. University of California Press. p. 163, Appendix 5B. ISBN 978-0-520-20029-6.

- ^ Sartori, L. (1996). Understanding Relativity. University of California Press. pp. 304–305. ISBN 978-0-520-20029-6.

- ^ Matts Roos, Introduction to Cosmology

- ^ Scharping, Nathaniel (18 October 2017). "Gravitational Waves Show How Fast The Universe is Expanding". Astronomy. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- ^ a b Chase, S. I.; Baez, J. C. (2004). "Olbers' Paradox". The Original Usenet Physics FAQ. Retrieved 2013-10-17.

- ^ a b Asimov, I. (1974). "The Black of Night". Asimov on Astronomy. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-04111-9.

- ^ Peebles, P. J. E. (1993). Principles of Physical Cosmology. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-07428-3.

- ^ Perlmutter, S. (2003). "Supernovae, Dark Energy, and the Accelerating Universe" (PDF). Physics Today. 56 (4): 53–60. Bibcode:2003PhT....56d..53P. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.77.7990. doi:10.1063/1.1580050. OSTI 1032838. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ Carroll, Sean (2004). Spacetime and Geometry: An Introduction to General Relativity (illustrated ed.). San Francisco: Addison-Wesley. p. 328. ISBN 978-0-8053-8732-2.

- ^ Heneka, C.; Amendola, L. (2018). "General modified gravity with 21cm intensity mapping: simulations and forecast". Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics. 2018 (10): 004. arXiv:1805.03629. Bibcode:2018JCAP...10..004H. doi:10.1088/1475-7516/2018/10/004. S2CID 119224326.

- ^ Hawley, John F.; Holcomb, Katherine A. (2005). Foundations of modern cosmology (2nd ed.). Oxford [u.a.]: Oxford University Press. p. 304. ISBN 978-0-19-853096-1.

- ^ Ridpath, Ian (2012). A Dictionary of Astronomy (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 225. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199609055.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-960905-5.

- ^ a b Bucher, P. A. R.; et al. (Planck Collaboration) (2013). "Planck 2013 results. I. Overview of products and scientific Results". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 571: A1. arXiv:1303.5062. Bibcode:2014A&A...571A...1P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201321529. S2CID 218716838.

- ^ a b c d e f g Verde, Licia; Schöneberg, Nils; Gil-Marín, Héctor (2024-09-13). "A Tale of Many H0". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 62: 287–331. doi:10.1146/annurev-astro-052622-033813. ISSN 0066-4146.

- ^ a b Allen, Nick. "Section 2: The Great Debate and the Great Mistake: Shapley, Hubble, Baade". The Cepheid Distance Scale: A History. Archived from the original on 10 December 2007. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ^ Baade, W. (1944) The resolution of Messier 32, NGC 205, and the central region of the Andromeda nebula. ApJ 100 137–146

- ^ Baade, W. (1956) The period-luminosity relation of the Cepheids. PASP 68 5–16

- ^ a b Overbye, D. (1999). "Prologue". Lonely Hearts of the Cosmos (2nd ed.). HarperCollins. p. 1ff. ISBN 978-0-316-64896-7.

- ^ a b de Vaucouleurs, G. (1982). The cosmic distance scale and the Hubble constant. Mount Stromlo and Siding Spring Observatories, Australian National University.

- ^ Myers, S. T. (1999). "Scaling the universe: Gravitational lenses and the Hubble constant". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (8): 4236–4239. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.4236M. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.8.4236. PMC 33560. PMID 10200245.

- ^ Turner, Michael S. (2022-09-26). "The Road to Precision Cosmology". Annual Review of Nuclear and Particle Science. 72: 1–35. arXiv:2201.04741. Bibcode:2022ARNPS..72....1T. doi:10.1146/annurev-nucl-111119-041046. ISSN 0163-8998.

- ^ Freedman, Wendy L.; Madore, Barry F. (2023-11-01). "Progress in direct measurements of the Hubble constant". Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics. 2023 (11) 050. arXiv:2309.05618. Bibcode:2023JCAP...11..050F. doi:10.1088/1475-7516/2023/11/050. ISSN 1475-7516.

- ^ Mann, Adam (26 August 2019). "One Number Shows Something Is Fundamentally Wrong with Our Conception of the Universe – This fight has universal implications". Live Science. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- ^ a b c d e di Valentino, Eleonora; et al. (2021). "In the realm of the Hubble tension—a review of solutions". Classical and Quantum Gravity. 38 (15) 153001. arXiv:2103.01183. Bibcode:2021CQGra..38o3001D. doi:10.1088/1361-6382/ac086d. S2CID 232092525.

- ^ a b Planck Collaboration; Aghanim, N.; et al. (2018). "Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 641 A6. arXiv:1807.06209. Bibcode:2020A&A...641A...6P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201833910.

- ^ Ananthaswamy, Anil (22 March 2019). "Best-Yet Measurements Deepen Cosmological Crisis". Scientific American. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- ^ Riess, Adam G.; Anand, Gagandeep S.; Yuan, Wenlong; Casertano, Stefano; Dolphin, Andrew; Macri, Lucas M.; Breuval, Louise; Scolnic, Dan; Perrin, Marshall (2023-07-28), "Crowded No More: The Accuracy of the Hubble Constant Tested with High Resolution Observations of Cepheids by JWST", The Astrophysical Journal, 956 (1) L18, arXiv:2307.15806, Bibcode:2023ApJ...956L..18R, doi:10.3847/2041-8213/acf769

- ^ "Webb Confirms Accuracy of Universe's Expansion Rate Measured by Hubble, Deepens Mystery of Hubble Constant Tension – James Webb Space Telescope". blogs.nasa.gov. 2023-09-12. Retrieved 2024-02-15.

- ^ a b Riess, Adam G.; Casertano, Stefano; Yuan, Wenlong; Macri, Lucas M.; Scolnic, Dan (18 March 2019). "Large Magellanic Cloud Cepheid Standards Provide a 1% Foundation for the Determination of the Hubble Constant and Stronger Evidence for Physics Beyond LambdaCDM". The Astrophysical Journal. 876 (1) 85. arXiv:1903.07603. Bibcode:2019ApJ...876...85R. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ab1422. S2CID 85528549.

- ^ Riess, Adam G.; Yuan, Wenlong; Macri, Lucas M.; Scolnic, Dan; Brout, Dillon; Casertano, Stefano; Jones, David O.; Murakami, Yukei; Anand, Gagandeep S.; Breuval, Louise; Brink, Thomas G.; Filippenko, Alexei V.; Hoffmann, Samantha; Jha, Saurabh W.; Kenworthy, W. D'arcy (July 2022). "A Comprehensive Measurement of the Local Value of the Hubble Constant with 1 km s−1 Mpc−1 Uncertainty from the Hubble Space Telescope and the SH0ES Team". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 934 (1): L7. arXiv:2112.04510. Bibcode:2022ApJ...934L...7R. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ac5c5b. ISSN 2041-8205.

- ^ Millea, Marius; Knox, Lloyd (2019-08-10). "Hubble constant hunter's guide". Physical Review D. 101 (4) 043533. arXiv:1908.03663. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.101.043533.

- ^ Riess, Adam G.; Anand, Gagandeep S.; Yuan, Wenlong; Casertano, Stefano; Dolphin, Andrew; Macri, Lucas M.; Breuval, Louise; Scolnic, Dan; Perrin, Marshall; Anderson, Richard I. (2023-10-01). "Crowded No More: The Accuracy of the Hubble Constant Tested with High-resolution Observations of Cepheids by JWST". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 956 (1): L18. arXiv:2307.15806. Bibcode:2023ApJ...956L..18R. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/acf769. ISSN 2041-8205.

- ^ Refsdal, S. (1 September 1964). "On the Possibility of Determining Hubble's Parameter and the Masses of Galaxies from the Gravitational Lens Effect". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 128 (4): 307–310. doi:10.1093/mnras/128.4.307.

- ^ Bronikowski, M.; Petrushevska, T.; Pierel, J. D. R.; Acebron, A.; Donevski, D.; Apostolova, B.; Blagorodnova, N.; Jankovič, T. (2025). "Cluster-lensed supernova yields from the Vera C. Rubin Observatory and Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 697: A146. arXiv:2504.01068. Bibcode:2025A&A...697A.146B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202451457.

- ^ Lerner, Louise (22 October 2018). "Gravitational waves could soon provide measure of universe's expansion". Phys.org. Retrieved 22 October 2018.

- ^ Chen, Hsin-Yu; Fishbach, Maya; Holz, Daniel E. (17 October 2018). "A two per cent Hubble constant measurement from standard sirens within five years". Nature. 562 (7728): 545–547. arXiv:1712.06531. Bibcode:2018Natur.562..545C. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0606-0. PMID 30333628. S2CID 52987203.

- ^ National Radio Astronomy Observatory (8 July 2019). "New method may resolve difficulty in measuring universe's expansion – Neutron star mergers can provide new 'cosmic ruler'". EurekAlert!. Archived from the original on 8 July 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ Finley, Dave (8 July 2019). "New Method May Resolve Difficulty in Measuring Universe's Expansion". National Radio Astronomy Observatory. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ a b Hotokezaka, K.; et al. (8 July 2019). "A Hubble constant measurement from superluminal motion of the jet in GW170817". Nature Astronomy. 3 (10): 940–944. arXiv:1806.10596. Bibcode:2019NatAs...3..940H. doi:10.1038/s41550-019-0820-1. S2CID 119547153.

- ^ a b Carnegie Institution of Science (16 July 2019). "New measurement of universe's expansion rate is 'stuck in the middle' – Red giant stars observed by Hubble Space Telescope used to make an entirely new measurement of how fast the universe is expanding". EurekAlert!. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- ^ a b Sokol, Joshua (19 July 2019). "Debate intensifies over speed of expanding universe". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aay8123. S2CID 200021863. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

- ^ a b Freedman, Wendy L.; Madore, Barry F.; Hatt, Dylan; Hoyt, Taylor J.; Jang, In-Sung; Beaton, Rachael L.; et al. (2019). "The Carnegie-Chicago Hubble Program. VIII. An Independent Determination of the Hubble Constant Based on the Tip of the Red Giant Branch". The Astrophysical Journal. 882 (1) 34. arXiv:1907.05922. Bibcode:2019ApJ...882...34F. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ab2f73. S2CID 196623652.

- ^ a b Pesce, D. W.; Braatz, J. A.; Reid, M. J.; Riess, A. G.; et al. (26 February 2020). "The Megamaser Cosmology Project. XIII. Combined Hubble Constant Constraints". The Astrophysical Journal. 891 (1) L1. arXiv:2001.09213. Bibcode:2020ApJ...891L...1P. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ab75f0. S2CID 210920444.

- ^ Castelvecchi, Davide (2020-07-15). "Mystery over Universe's expansion deepens with fresh data". Nature. 583 (7817): 500–501. Bibcode:2020Natur.583..500C. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-02126-6. PMID 32669728. S2CID 220583383.

- ^ a b c Sneppen, Albert; Watson, Darach; Poznanski, Dovi; Just, Oliver; Bauswein, Andreas; Wojtak, Radosław (2023-10-01). "Measuring the Hubble constant with kilonovae using the expanding photosphere method". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 678 A14. arXiv:2306.12468. Bibcode:2023A&A...678A..14S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202346306. ISSN 0004-6361.

- ^ Sneppen, Albert (2023-09-01). "On the Blackbody Spectrum of Kilonovae". The Astrophysical Journal. 955 (1) 44. arXiv:2306.05452. Bibcode:2023ApJ...955...44S. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/acf200. ISSN 0004-637X.

- ^ a b Sneppen, Albert; Watson, Darach; Bauswein, Andreas; Just, Oliver; Kotak, Rubina; Nakar, Ehud; Poznanski, Dovi; Sim, Stuart (February 2023). "Spherical symmetry in the kilonova AT2017gfo/GW170817". Nature. 614 (7948): 436–439. arXiv:2302.06621. Bibcode:2023Natur.614..436S. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-05616-x. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 36792736. S2CID 256846834.

- ^ Gresko, Michael (17 December 2021). "The universe is expanding faster than it should be". National Geographic. Archived from the original on December 17, 2021. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ Abdalla, Elcio; Abellán, Guillermo Franco; Aboubrahim, Amin (11 Mar 2022), "Cosmology Intertwined: A Review of the Particle Physics, Astrophysics, and Cosmology Associated with the Cosmological Tensions and Anomalies", Journal of High Energy Astrophysics, 34: 49, arXiv:2203.06142, Bibcode:2022JHEAp..34...49A, doi:10.1016/j.jheap.2022.04.002, S2CID 247411131

- ^ Vagnozzi, Sunny (2020-07-10). "New physics in light of the H0 tension: An alternative view". Physical Review D. 102 (2) 023518. arXiv:1907.07569. Bibcode:2020PhRvD.102b3518V. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.102.023518. S2CID 197430820.

- ^ Haslbauer, M.; Banik, I.; Kroupa, P. (2020-12-21). "The KBC void and Hubble tension contradict LCDM on a Gpc scale – Milgromian dynamics as a possible solution". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 499 (2): 2845–2883. arXiv:2009.11292. Bibcode:2020MNRAS.499.2845H. doi:10.1093/mnras/staa2348. ISSN 0035-8711.

- ^ Mazurenko, S.; Banik, I.; Kroupa, P.; Haslbauer, M. (2024-01-21). "A simultaneous solution to the Hubble tension and observed bulk flow within 250/h Mpc". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 527 (3): 4388–4396. arXiv:2311.17988. Bibcode:2024MNRAS.527.4388M. doi:10.1093/mnras/stad3357. ISSN 0035-8711.

- ^ Poulin, Vivian; Smith, Tristan L.; Karwal, Tanvi; Kamionkowski, Marc (2019-06-04). "Early Dark Energy can Resolve the Hubble Tension". Physical Review Letters. 122 (22) 221301. arXiv:1811.04083. Bibcode:2019PhRvL.122v1301P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.122.221301. PMID 31283280. S2CID 119233243.

- ^ Zhao, Gong-Bo; Raveri, Marco; Pogosian, Levon; Wang, Yuting; Crittenden, Robert G.; Handley, Will J.; Percival, Will J.; Beutler, Florian; Brinkmann, Jonathan; Chuang, Chia-Hsun; Cuesta, Antonio J.; Eisenstein, Daniel J.; Kitaura, Francisco-Shu; Koyama, Kazuya; l'Huillier, Benjamin; Nichol, Robert C.; Pieri, Matthew M.; Rodriguez-Torres, Sergio; Ross, Ashley J.; Rossi, Graziano; Sánchez, Ariel G.; Shafieloo, Arman; Tinker, Jeremy L.; Tojeiro, Rita; Vazquez, Jose A.; Zhang, Hanyu (2017). "Dynamical dark energy in light of the latest observations". Nature Astronomy. 1 (9): 627–632. arXiv:1701.08165. Bibcode:2017NatAs...1..627Z. doi:10.1038/s41550-017-0216-z. S2CID 256705070.

- ^ Berezhiani, Zurab; Dolgov, A. D.; Tkachev, I. I. (2015). "Reconciling Planck results with low redshift astronomical measurements". Physical Review D. 92 (6) 061303. arXiv:1505.03644. Bibcode:2015PhRvD..92f1303B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.92.061303. S2CID 118169478.

- ^ Laila Linke (17 May 2021). "Solving the Hubble tension might require more than changing the early Universe". Astrobites.

- ^ Vagnozzi, Sunny (2023-08-30). "Seven Hints That Early-Time New Physics Alone Is Not Sufficient to Solve the Hubble Tension". Universe. 9 (9) 393. arXiv:2308.16628. Bibcode:2023Univ....9..393V. doi:10.3390/universe9090393.

- ^ Ryan E. Keeley and Arman Shafieloo (August 2023). "Ruling Out New Physics at Low Redshift as a Solution to the H0 Tension". Physical Review Letters. 131 (11) 111002. arXiv:2206.08440. Bibcode:2023PhRvL.131k1002K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.131.111002. PMID 37774270. S2CID 249848075.

- ^ Freedman, Wendy L.; Madore, Barry F.; Hoyt, Taylor J.; Jang, In Sung; Lee, Abigail J.; Owens, Kayla A. (2025-06-01). "Status Report on the Chicago-Carnegie Hubble Program (CCHP): Measurement of the Hubble Constant Using the Hubble and James Webb Space Telescopes". The Astrophysical Journal. 985 (2): 203. arXiv:2408.06153. Bibcode:2025ApJ...985..203F. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/adce78. ISSN 0004-637X.

- ^ Kruesi, Liz (2024-08-13). "The Webb Telescope Further Deepens the Biggest Controversy in Cosmology". Quanta Magazine. Retrieved 2024-08-17.

- ^ Pascale, Massimo; Frye, Brenda L.; Pierel, Justin D.R.; Chen, Wenlei; Kelly, Patrick L.; Cohen, Seth H.; Windhorst, Rogier A.; Riess, Adam G.; Kamieneski, Patrick S.; Diego, Jos'e M.; Meena, Ashish K.; Cha, Sangjun; Oguri, Masamune; Zitrin, Adi; Jee, M. James (2025-01-14). "SN H0pe: The First Measurement of H0 from a Multiply Imaged Type Ia Supernova, Discovered by JWST". The Astrophysical Journal. 979 (1): 13. arXiv:2403.18902. Bibcode:2025ApJ...979...13P. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ad9928. ISSN 0004-637X.

- ^ Riess, Adam G.; Scolnic, Dan; Anand, Gagandeep S.; Breuval, Louise; Casertano, Stefano; Macri, Lucas M.; Li, Siyang; Yuan, Wenlong; Huang, Caroline D.; Jha, Saurabh; Murakami, Yukei S.; Beaton, Rachael; Brout, Dillon; Wu, Tianrui; Addison, Graeme E.; Bennett, Charles; Anderson, Richard I.; Filippenko, Alexei V.; Carr, Anthony (2024). "JWST Validates HST Distance Measurements: Selection of Supernova Subsample Explains Differences in JWST Estimates of Local H 0". The Astrophysical Journal. 977 (1): 120. arXiv:2408.11770. Bibcode:2024ApJ...977..120R. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ad8c21.

- ^ Balkenhol, L.; Dutcher, D.; Spurio Mancini, A.; Doussot, A.; Benabed, K.; Galli, S.; et al. (SPT-3G Collaboration) (2023-07-13). "Measurement of the CMB temperature power spectrum and constraints on cosmology from the SPT-3G 2018 T T, T E, and E E dataset". Physical Review D. 108 (2) 023510. arXiv:2212.05642. Bibcode:2023PhRvD.108b3510B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.108.023510. ISSN 2470-0010.

- ^ Kelly, P. L.; Rodney, S.; Treu, T.; Oguri, M.; Chen, W.; Zitri, A.; et al. (2023-05-11). "Constraints on the Hubble constant from Supernova Refsdal's reappearance". Science. 380 (6649) eabh1322. arXiv:2305.06367. Bibcode:2023Sci...380.1322K. doi:10.1126/science.abh1322. PMID 37167351. S2CID 258615332.

- ^ Contarini, Sofia; Pisani, Alice; Hamaus, Nico; Marulli, Federico; Moscardini, Lauro; Baldi, Marco (2024). "The perspective of voids on rising cosmology tensions". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 682 A20. arXiv:2212.07438. Bibcode:2024A&A...682A..20C. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202347572.

- ^ Chiou, Lyndie (2023-07-25). "How (Nearly) Nothing Might Solve Cosmology's Biggest Questions". Quanta Magazine. Retrieved 2023-07-31.