Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

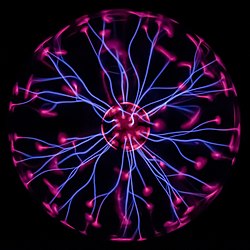

Electromagnetism

View on Wikipedia

| Electromagnetism |

|---|

|

In physics, electromagnetism is an interaction that occurs between particles with electric charge via electromagnetic fields. The electromagnetic force is one of the four fundamental forces of nature.[1] It is the dominant force in the interactions of atoms and molecules. Electromagnetism can be thought of as a combination of electrostatics and magnetism, which are distinct but closely intertwined phenomena. Electromagnetic forces occur between any two charged particles. Electric forces cause an attraction between particles with opposite charges and repulsion between particles with the same charge, while magnetism is an interaction that occurs between charged particles in relative motion. These two forces are described in terms of electromagnetic fields. Macroscopic charged objects are described in terms of Coulomb's law for electricity and Ampère's force law for magnetism; the Lorentz force describes microscopic charged particles.

The electromagnetic force is responsible for many of the chemical and physical phenomena observed in daily life. The electrostatic attraction between atomic nuclei and their electrons holds atoms together. Electric forces also allow different atoms to combine into molecules, including the macromolecules such as proteins that form the basis of life. Meanwhile, magnetic interactions between the spin and angular momentum magnetic moments of electrons also play a role in chemical reactivity; such relationships are studied in spin chemistry. Electromagnetism also plays several crucial roles in modern technology: electrical energy production, transformation and distribution; light, heat, and sound production and detection; fiber optic and wireless communication; sensors; computation; electrolysis; electroplating; and mechanical motors and actuators.

Electromagnetism has been studied since ancient times. Many ancient civilizations, including the Greeks and the Mayans, created wide-ranging theories to explain lightning, static electricity, and the attraction between magnetized pieces of iron ore. However, it was not until the late 18th century that scientists began to develop a mathematical basis for understanding the nature of electromagnetic interactions. In the 18th and 19th centuries, prominent scientists and mathematicians such as Coulomb, Gauss and Faraday developed namesake laws which helped to explain the formation and interaction of electromagnetic fields. This process culminated in the 1860s with the discovery of Maxwell's equations, a set of four partial differential equations which provide a complete description of classical electromagnetic fields. Maxwell's equations provided a sound mathematical basis for the relationships between electricity and magnetism that scientists had been exploring for centuries, and predicted the existence of self-sustaining electromagnetic waves. Maxwell postulated that such waves make up visible light, which was later shown to be true. Gamma-rays, x-rays, ultraviolet, visible, infrared radiation, microwaves and radio waves were all determined to be electromagnetic radiation differing only in their range of frequencies.

In the modern era, scientists continue to refine the theory of electromagnetism to account for the effects of modern physics, including quantum mechanics and relativity. The theoretical implications of electromagnetism, particularly the requirement that observations remain consistent when viewed from various moving frames of reference (relativistic electromagnetism) and the establishment of the speed of light based on properties of the medium of propagation (permeability and permittivity), helped inspire Einstein's theory of special relativity in 1905. Quantum electrodynamics (QED) modifies Maxwell's equations to be consistent with the quantized nature of matter. In QED, changes in the electromagnetic field are expressed in terms of discrete excitations, particles known as photons, the quanta of light.

History

[edit]Ancient world

[edit]Investigation into electromagnetic phenomena began about 5,000 years ago. There is evidence that the ancient Chinese,[2] Mayan,[3][4] and potentially even Egyptian civilizations knew that the naturally magnetic mineral magnetite had attractive properties, and many incorporated it into their art and architecture.[5] Ancient people were also aware of lightning and static electricity, although they had no idea of the mechanisms behind these phenomena. The Greek philosopher Thales of Miletus discovered around 600 B.C.E. that amber could acquire an electric charge when it was rubbed with cloth, which allowed it to pick up light objects such as pieces of straw. Thales also experimented with the ability of magnetic rocks to attract one other, and hypothesized that this phenomenon might be connected to the attractive power of amber, foreshadowing the deep connections between electricity and magnetism that would be discovered over 2,000 years later. Despite all this investigation, ancient civilizations had no understanding of the mathematical basis of electromagnetism, and often analyzed its impacts through the lens of religion rather than science (lightning, for instance, was considered to be a creation of the gods in many cultures).[6]

19th century

[edit]

Electricity and magnetism were originally considered to be two separate forces. This view changed with the publication of James Clerk Maxwell's 1873 A Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism[7] in which the interactions of positive and negative charges were shown to be mediated by one force. There are four main effects resulting from these interactions, all of which have been clearly demonstrated by experiments:

- Electric charges attract or repel one another with a force inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them: opposite charges attract, like charges repel.[8]

- Magnetic poles (or states of polarization at individual points) attract or repel one another in a manner similar to positive and negative charges and always exist as pairs: every north pole is yoked to a south pole.[9]

- An electric current inside a wire creates a corresponding circumferential magnetic field outside the wire. Its direction (clockwise or counter-clockwise) depends on the direction of the current in the wire.[10]

- A current is induced in a loop of wire when it is moved toward or away from a magnetic field, or a magnet is moved towards or away from it; the direction of current depends on that of the movement.[10]

In April 1820, Hans Christian Ørsted observed that an electrical current in a wire caused a nearby compass needle to move. At the time of discovery, Ørsted did not suggest any satisfactory explanation of the phenomenon, nor did he try to represent the phenomenon in a mathematical framework. However, three months later he began more intensive investigations.[11][12] Soon thereafter he published his findings, proving that an electric current produces a magnetic field as it flows through a wire. The CGS unit of magnetic induction (oersted) is named in honor of his contributions to the field of electromagnetism.[13]

His findings resulted in intensive research throughout the scientific community in electrodynamics. They influenced French physicist André-Marie Ampère's developments of a single mathematical form to represent the magnetic forces between current-carrying conductors. Ørsted's discovery also represented a major step toward a unified concept of energy.

This unification, which was observed by Michael Faraday, extended by James Clerk Maxwell, and partially reformulated by Oliver Heaviside and Heinrich Hertz, is one of the key accomplishments of 19th-century mathematical physics.[14] It has had far-reaching consequences, one of which was the understanding of the nature of light. Unlike what was proposed by the electromagnetic theory of that time, light and other electromagnetic waves are at present seen as taking the form of quantized, self-propagating oscillatory electromagnetic field disturbances called photons. Different frequencies of oscillation give rise to the different forms of electromagnetic radiation, from radio waves at the lowest frequencies, to visible light at intermediate frequencies, to gamma rays at the highest frequencies.

Ørsted was not the only person to examine the relationship between electricity and magnetism. In 1802, Gian Domenico Romagnosi, an Italian legal scholar, deflected a magnetic needle using a Voltaic pile. The factual setup of the experiment is not completely clear, nor if current flowed across the needle or not. An account of the discovery was published in 1802 in an Italian newspaper, but it was largely overlooked by the contemporary scientific community, because Romagnosi seemingly did not belong to this community.[15]

An earlier (1735), and often neglected, connection between electricity and magnetism was reported by a Dr. Cookson.[16] The account stated:

A tradesman at Wakefield in Yorkshire, having put up a great number of knives and forks in a large box ... and having placed the box in the corner of a large room, there happened a sudden storm of thunder, lightning, &c. ... The owner emptying the box on a counter where some nails lay, the persons who took up the knives, that lay on the nails, observed that the knives took up the nails. On this the whole number was tried, and found to do the same, and that, to such a degree as to take up large nails, packing needles, and other iron things of considerable weight ...

E. T. Whittaker suggested in 1910 that this particular event was responsible for lightning to be "credited with the power of magnetizing steel; and it was doubtless this which led Franklin in 1751 to attempt to magnetize a sewing-needle by means of the discharge of Leyden jars."[17]

A fundamental force

[edit]

The electromagnetic force is the second strongest of the four known fundamental forces and has unlimited range.[18] All other forces, known as non-fundamental forces.[19] (e.g., friction, contact forces) are derived from the four fundamental forces. At high energy, the weak force and electromagnetic force are unified as a single interaction called the electroweak interaction.[20]

Most of the forces involved in interactions between atoms are explained by electromagnetic forces between electrically charged atomic nuclei and electrons. The electromagnetic force is also involved in all forms of chemical phenomena.

Electromagnetism explains how materials carry momentum despite being composed of individual particles and empty space. The forces we experience when "pushing" or "pulling" ordinary material objects result from intermolecular forces between individual molecules in our bodies and in the objects.

The effective forces generated by the momentum of electrons' movement is a necessary part of understanding atomic and intermolecular interactions. As electrons move between interacting atoms, they carry momentum with them. As a collection of electrons becomes more confined, their minimum momentum necessarily increases due to the Pauli exclusion principle. The behavior of matter at the molecular scale, including its density, is determined by the balance between the electromagnetic force and the force generated by the exchange of momentum carried by the electrons themselves.[21]

Classical electrodynamics

[edit]In 1600, William Gilbert proposed, in his De Magnete, that electricity and magnetism, while both capable of causing attraction and repulsion of objects, were distinct effects.[22] Mariners had noticed that lightning strikes had the ability to disturb a compass needle. The link between lightning and electricity was not confirmed until Benjamin Franklin's proposed experiments in 1752 were conducted on 10 May 1752 by Thomas-François Dalibard of France using a 40-foot-tall (12 m) iron rod instead of a kite and he successfully extracted electrical sparks from a cloud.[23][24]

One of the first to discover and publish a link between human-made electric current and magnetism was Gian Romagnosi, who in 1802 noticed that connecting a wire across a voltaic pile deflected a nearby compass needle. However, the effect did not become widely known until 1820, when Ørsted performed a similar experiment.[25] Ørsted's work influenced Ampère to conduct further experiments, which eventually gave rise to a new area of physics: electrodynamics. By determining a force law for the interaction between elements of electric current, Ampère placed the subject on a solid mathematical foundation.[26]

A theory of electromagnetism, known as classical electromagnetism, was developed by several physicists during the period between 1820 and 1873, when James Clerk Maxwell's treatise was published, which unified previous developments into a single theory, proposing that light was an electromagnetic wave propagating in the luminiferous ether.[27] In classical electromagnetism, the behavior of the electromagnetic field is described by a set of equations known as Maxwell's equations, and the electromagnetic force is given by the Lorentz force law.[28]

One of the peculiarities of classical electromagnetism is that it is difficult to reconcile with classical mechanics, but it is compatible with special relativity. According to Maxwell's equations, the speed of light in vacuum is a universal constant that is dependent only on the electrical permittivity and magnetic permeability of free space. This violates Galilean invariance, a long-standing cornerstone of classical mechanics. One way to reconcile the two theories (electromagnetism and classical mechanics) is to assume the existence of a luminiferous aether through which the light propagates. However, subsequent experimental efforts failed to detect the presence of the aether. After important contributions of Hendrik Lorentz and Henri Poincaré, in 1905, Albert Einstein solved the problem with the introduction of special relativity, which replaced classical kinematics with a new theory of kinematics compatible with classical electromagnetism. (For more information, see History of special relativity.)

In addition, relativity theory implies that in moving frames of reference, a magnetic field transforms to a field with a nonzero electric component and conversely, a moving electric field transforms to a nonzero magnetic component, thus firmly showing that the phenomena are two sides of the same coin. Hence the term "electromagnetism". (For more information, see Classical electromagnetism and special relativity and Covariant formulation of classical electromagnetism.)

Today few problems in electromagnetism remain unsolved. These include: the lack of magnetic monopoles, Abraham–Minkowski controversy, the location in space of the electromagnetic field energy,[29] and the mechanism by which some organisms can sense electric and magnetic fields.

Extension to nonlinear phenomena

[edit]The Maxwell equations are linear, in that a change in the sources (the charges and currents) results in a proportional change of the fields. Nonlinear dynamics can occur when electromagnetic fields couple to matter that follows nonlinear dynamical laws.[30] This is studied, for example, in the subject of magnetohydrodynamics, which combines Maxwell theory with the Navier–Stokes equations.[31] Another branch of electromagnetism dealing with nonlinearity is nonlinear optics.

Quantities and units

[edit]Here is a list of common units related to electromagnetism:[32]

In the electromagnetic CGS system, electric current is a fundamental quantity defined via Ampère's law and takes the permeability as a dimensionless quantity (relative permeability) whose value in vacuum is unity.[33] As a consequence, the square of the speed of light appears explicitly in some of the equations interrelating quantities in this system.

| Symbol[34] | Name of quantity | Unit name | Symbol | Base units |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E | energy | joule | J = C⋅V = W⋅s | kg⋅m2⋅s−2 |

| Q | electric charge | coulomb | C | A⋅s |

| I | electric current | ampere | A = C/s = W/V | A |

| J | electric current density | ampere per square metre | A/m2 | A⋅m−2 |

| U, ΔV; Δϕ; E, ξ | potential difference; voltage; electromotive force | volt | V = J/C | kg⋅m2⋅s−3⋅A−1 |

| R; Z; X | electric resistance; impedance; reactance | ohm | Ω = V/A | kg⋅m2⋅s−3⋅A−2 |

| ρ | resistivity | ohm metre | Ω⋅m | kg⋅m3⋅s−3⋅A−2 |

| P | electric power | watt | W = V⋅A | kg⋅m2⋅s−3 |

| C | capacitance | farad | F = C/V | kg−1⋅m−2⋅A2⋅s4 |

| ΦE | electric flux | volt metre | V⋅m | kg⋅m3⋅s−3⋅A−1 |

| E | electric field strength | volt per metre | V/m = N/C | kg⋅m⋅A−1⋅s−3 |

| D | electric displacement field | coulomb per square metre | C/m2 | A⋅s⋅m−2 |

| ε | permittivity | farad per metre | F/m | kg−1⋅m−3⋅A2⋅s4 |

| χe | electric susceptibility | (dimensionless) | 1 | 1 |

| p | electric dipole moment | coulomb metre | C⋅m | A⋅s⋅m |

| G; Y; B | conductance; admittance; susceptance | siemens | S = Ω−1 | kg−1⋅m−2⋅s3⋅A2 |

| κ, γ, σ | conductivity | siemens per metre | S/m | kg−1⋅m−3⋅s3⋅A2 |

| B | magnetic flux density, magnetic induction | tesla | T = Wb/m2 = N⋅A−1⋅m−1 | kg⋅s−2⋅A−1 |

| Φ, ΦM, ΦB | magnetic flux | weber | Wb = V⋅s | kg⋅m2⋅s−2⋅A−1 |

| H | magnetic field strength | ampere per metre | A/m | A⋅m−1 |

| F | magnetomotive force | ampere | A = Wb/H | A |

| R | magnetic reluctance | inverse henry | H−1 = A/Wb | kg−1⋅m−2⋅s2⋅A2 |

| P | magnetic permeance | henry | H = Wb/A | kg⋅m2⋅s–2⋅A–2 |

| L, M | inductance | henry | H = Wb/A = V⋅s/A | kg⋅m2⋅s−2⋅A−2 |

| μ | permeability | henry per metre | H/m | kg⋅m⋅s−2⋅A−2 |

| χ | magnetic susceptibility | (dimensionless) | 1 | 1 |

| m | magnetic dipole moment | ampere square meter | A⋅m2 = J⋅T−1 | A⋅m2 |

| σ | mass magnetization | ampere square meter per kilogram | A⋅m2/kg | A⋅m2⋅kg−1 |

Formulas for physical laws of electromagnetism (such as Maxwell's equations) need to be adjusted depending on what system of units one uses. This is because there is no one-to-one correspondence between electromagnetic units in SI and those in CGS, as is the case for mechanical units. Furthermore, within CGS, there are several plausible choices of electromagnetic units, leading to different unit "sub-systems", including Gaussian, "ESU", "EMU", and Heaviside–Lorentz. Among these choices, Gaussian units are the most common today, and in fact the phrase "CGS units" is often used to refer specifically to CGS-Gaussian units.[35]

Applications

[edit]The study of electromagnetism informs electric circuits, magnetic circuits, and semiconductor devices' construction.

See also

[edit]- Abraham–Lorentz force

- Aeromagnetic surveys

- Computational electromagnetics

- Double-slit experiment

- Electrodynamic droplet deformation

- Electromagnet

- Electromagnetic induction

- Electromagnetic wave equation

- Electromagnetic scattering

- Electromechanics

- Geophysics

- Introduction to electromagnetism

- Magnetostatics

- Magnetoquasistatic field

- Optics

- Relativistic electromagnetism

- Wheeler–Feynman absorber theory

References

[edit]- ^ Biggs, Ben; Rehm, Jeremy (2021-12-23). "The four fundamental forces of nature". Space. Retrieved 2025-08-15.

- ^ Meyer, Herbert (1972). A History of Electricity and Magnetism. p. 2.

- ^ Learn, Joshua Rapp. "Mesoamerican Sculptures Reveal Early Knowledge of Magnetism". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on 2022-12-07. Retrieved 2022-12-07. Summary of paper by Fu et al.

- ^ Fu, Roger R.; Kirschvink, Joseph L.; Carter, Nicholas; Mazariegos, Oswaldo Chinchilla; Chigna, Gustavo; Gupta, Garima; Grappone, Michael (2019-06-01). "Knowledge of magnetism in ancient Mesoamerica: Precision measurements of the potbelly sculptures from Monte Alto, Guatemala". Journal of Archaeological Science. 106: 29–36. Bibcode:2019JArSc.106...29F. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2019.03.001. ISSN 0305-4403.

- ^ du Trémolet de Lacheisserie, É.; Gignoux, D.; Schlenker, M. (2002), du Trémolet de Lacheisserie, É.; Gignoux, D.; Schlenker, M. (eds.), "Magnetism, from the Dawn of Civilization to Today", Magnetism, New York, NY: Springer, pp. 3–18, doi:10.1007/978-0-387-23062-7_1, ISBN 978-0-387-23062-7, archived from the original on 2024-10-03, retrieved 2022-12-07

- ^ Meyer, Herbert (1972). A History of Electricity and Magnetism. pp. 3–4.

- ^ "A Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism". Nature. 7 (182): 478–480. 24 April 1873. Bibcode:1873Natur...7..478.. doi:10.1038/007478a0. ISSN 0028-0836. S2CID 10178476. Archived from the original on 23 October 2021. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- ^ "Why Do Like Charges Repel And Opposite Charges Attract?". Science ABC. 2019-02-06. Archived from the original on 2022-08-22. Retrieved 2022-08-22.

- ^ "What Makes Magnets Repel?". Sciencing. 27 December 2020. Archived from the original on 2022-09-26. Retrieved 2022-08-22.

- ^ a b Jim Lucas Contributions from Ashley Hamer (2022-02-18). "What Is Faraday's Law of Induction?". livescience.com. Archived from the original on 2022-08-22. Retrieved 2022-08-22.

- ^ "History of the Electric Telegraph". Scientific American. 17 (425supp): 6784–6786. 1884-02-23. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican02231884-6784supp. ISSN 0036-8733. Archived from the original on 2024-10-03. Retrieved 2022-02-08.

- ^ Bevilacqua, Fabio; Giannetto, Enrico A., eds. (2003). Volta and the history of electricity. Milano: U. Hoepli. ISBN 88-203-3284-1. OCLC 1261807533.

- ^ Roche, John J. (1998). The mathematics of measurement : a critical history. London: Athlone Press. ISBN 0-485-11473-9. OCLC 40499222.

- ^ Darrigol, Olivier (2000). Electrodynamics from Ampère to Einstein. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198505949.

- ^ Martins, Roberto de Andrade. "Romagnosi and Volta's Pile: Early Difficulties in the Interpretation of Voltaic Electricity" (PDF). In Fabio Bevilacqua; Lucio Fregonese (eds.). Nuova Voltiana: Studies on Volta and his Times. Vol. 3. Università degli Studi di Pavia. pp. 81–102. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-30. Retrieved 2010-12-02.

- ^ VIII. An account of an extraordinary effect of lightning in communicating magnetism. Communicated by Pierce Dod, M.D. F.R.S. from Dr. Cookson of Wakefield in Yorkshire. Phil. Trans. 1735 39, 74-75, published 1 January 1735

- ^ Whittaker, E.T. (1910). A History of the Theories of Aether and Electricity from the Age of Descartes to the Close of the Nineteenth Century. Longmans, Green and Company.

- ^ Rehm, Jeremy; published, Ben Biggs (2021-12-23). "The four fundamental forces of nature". Space.com. Archived from the original on 2022-08-22. Retrieved 2022-08-22.

- ^ Browne, "Physics for Engineering and Science", p. 160: "Gravity is one of the fundamental forces of nature. The other forces such as friction, tension, and the normal force are derived from the electric force, another of the fundamental forces. Gravity is a rather weak force... The electric force between two protons is much stronger than the gravitational force between them."

- ^ Salam, A.; Ward, J.C. (November 1964). "Electromagnetic and weak interactions". Physics Letters. 13 (2): 168–171. Bibcode:1964PhL....13..168S. doi:10.1016/0031-9163(64)90711-5. Archived from the original on 2024-04-16. Retrieved 2024-02-02.

- ^ Purcell, "Electricity and Magnetism, 3rd Edition", p. 546: Ch 11 Section 6, "Electron Spin and Magnetic Moment."

- ^ Malin, Stuart; Barraclough, David (2000). "Gilbert's De Magnete: An early study of magnetism and electricity". Eos, Transactions American Geophysical Union. 81 (21): 233. Bibcode:2000EOSTr..81..233M. doi:10.1029/00EO00163. ISSN 0096-3941. Archived from the original on 2024-10-03. Retrieved 2022-08-22.

- ^ "Lightning! | Museum of Science, Boston". Archived from the original on 2010-02-09. Retrieved 2022-08-22.

- ^ Tucker, Tom (2003). Bolt of fate : Benjamin Franklin and his electric kite hoax (1st ed.). New York: PublicAffairs. ISBN 1-891620-70-3. OCLC 51763922.

- ^ Stern, Dr. David P.; Peredo, Mauricio (2001-11-25). "Magnetic Fields – History". NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. Archived from the original on 2015-11-16. Retrieved 2009-11-27.

- ^ "Andre-Marie Ampère". ETHW. 2016-01-13. Archived from the original on 2022-08-22. Retrieved 2022-08-22.

- ^ Purcell, p. 436. Chapter 9.3, "Maxwell's description of the electromagnetic field was essentially complete."

- ^ Purcell: p. 278: Chapter 6.1, "Definition of the Magnetic Field." Lorentz force and force equation.

- ^ Feynman, Richard P. (2011). "27–4 The ambiguity of the field energy". The Feynman lectures on physics. Volume 1: Mainly mechanics, radiation, and heat (The new millennium edition, paperback first published ed.). New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-04085-8. Archived from the original on 2024-10-03. Retrieved 2024-09-05.

- ^ Jufriansah, Adi; Hermanto, Arief; Toifur, Moh.; Prasetyo, Erwin (2020-05-18). "Theoretical study of Maxwell's equations in nonlinear optics". AIP Conference Proceedings. 2234 (1): 040013. Bibcode:2020AIPC.2234d0013J. doi:10.1063/5.0008179. ISSN 0094-243X. S2CID 219451710.

- ^ Hunt, Julian C. R. (1967-07-27). Some aspects of magnetohydrodynamics (Thesis thesis). University of Cambridge. doi:10.17863/cam.14141. Archived from the original on 2022-08-22. Retrieved 2022-08-22.

- ^ "Essentials of the SI: Base & derived units". physics.nist.gov. 12 April 2010. Archived from the original on 2020-12-28. Retrieved 2022-08-22.

- ^ "Tables of Physical and Chemical Constants, and some Mathematical Functions". Nature. 107 (2687): 264. April 1921. Bibcode:1921Natur.107R.264.. doi:10.1038/107264c0. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ^ International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (1993). Quantities, Units and Symbols in Physical Chemistry, 2nd edition, Oxford: Blackwell Science. ISBN 0-632-03583-8. pp. 14–15. Electronic version.

- ^ "Conversion of formulae and quantities between unit systems" (PDF). www.stanford.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 October 2022. Retrieved 29 January 2022.

Further reading

[edit]Web sources

[edit]- Nave, R. "Electricity and magnetism". HyperPhysics. Georgia State University. Archived from the original on 2023-06-07. Retrieved 2013-11-12.

- Khutoryansky, E. (28 December 2014). "Electromagnetism – Maxwell's Laws". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2024-10-03. Retrieved 2014-12-28.

Textbooks

[edit]- G.A.G. Bennet (1974). Electricity and Modern Physics (2nd ed.). Edward Arnold (UK). ISBN 978-0-7131-2459-0.

- Browne, Michael (2008). Physics for Engineering and Science (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill/Schaum. ISBN 978-0-07-161399-6.

- Dibner, Bern (2012). Oersted and the discovery of electromagnetism. Literary Licensing, LLC. ISBN 978-1-258-33555-7.

- Durney, Carl H.; Johnson, Curtis C. (1969). Introduction to modern electromagnetics. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-018388-9.

- Feynman, Richard P. (1970). The Feynman Lectures on Physics Vol II. Addison Wesley Longman. ISBN 978-0-201-02115-8. Archived from the original on 2024-10-03. Retrieved 2022-05-01.

- Fleisch, Daniel (2008). A Student's Guide to Maxwell's Equations. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-70147-1.

- I.S. Grant; W.R. Phillips; Manchester Physics (2008). Electromagnetism (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-92712-9.

- Griffiths, David J. (1998). Introduction to Electrodynamics (3rd ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-805326-0.

- Jackson, John D. (1998). Classical Electrodynamics (3rd ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-30932-1.

- Moliton, André (2007). Basic electromagnetism and materials. New York: Springer-Verlag New York. ISBN 978-0-387-30284-3.

- Purcell, Edward M. (1985). Electricity and Magnetism Berkeley, Physics Course Volume 2 (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-004908-6.

- Purcell, Edward M and Morin, David. (2013). Electricity and Magnetism, 820p (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press, New York. ISBN 978-1-107-01402-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Rao, Nannapaneni N. (1994). Elements of engineering electromagnetics (4th ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-948746-0.

- Rothwell, Edward J.; Cloud, Michael J. (2001). Electromagnetics. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-1397-4.

- Tipler, Paul (1998). Physics for Scientists and Engineers: Vol. 2: Light, Electricity and Magnetism (4th ed.). W.H. Freeman. ISBN 978-1-57259-492-0.

- Wangsness, Roald K.; Cloud, Michael J. (1986). Electromagnetic Fields (2nd ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-81186-2.

General coverage

[edit]- A. Beiser (1987). Concepts of Modern Physics (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill (International). ISBN 978-0-07-100144-1.

- L.H. Greenberg (1978). Physics with Modern Applications. Holt-Saunders International W.B. Saunders and Co. ISBN 978-0-7216-4247-5.

- R.G. Lerner; G.L. Trigg (2005). Encyclopaedia of Physics (2nd ed.). VHC Publishers, Hans Warlimont, Springer. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-0-07-025734-4.

- J.B. Marion; W.F. Hornyak (1984). Principles of Physics. Holt-Saunders International Saunders College. ISBN 978-4-8337-0195-2.

- H.J. Pain (1983). The Physics of Vibrations and Waves (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-90182-2.

- C.B. Parker (1994). McGraw Hill Encyclopaedia of Physics (2nd ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-051400-3.

- R. Penrose (2007). The Road to Reality. Vintage books. ISBN 978-0-679-77631-4.

- P.A. Tipler; G. Mosca (2008). Physics for Scientists and Engineers: With Modern Physics (6th ed.). W.H. Freeman and Co. ISBN 978-1-4292-0265-7.

- P.M. Whelan; M.J. Hodgeson (1978). Essential Principles of Physics (2nd ed.). John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-3382-2.

External links

[edit]- Magnetic Field Strength Converter

- Electromagnetic Force – from Eric Weisstein's World of Physics