Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Beat (music)

View on Wikipedia

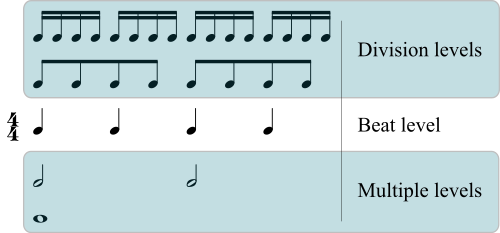

In music and music theory, the beat is the basic unit of time, the pulse (regularly repeating event), of the mensural level[1] (or beat level).[2] The beat is often defined as the rhythm listeners would tap their toes to when listening to a piece of music, or the numbers a musician counts while performing, though in practice this may be technically incorrect (often the first multiple level).[clarification needed] In popular use, beat can refer to a variety of related concepts, including pulse, tempo, meter, specific rhythms, and groove.

Rhythm in music is characterized by a repeating sequence of stressed and unstressed beats (often called "strong" and "weak") and divided into bars organized by time signature and tempo indications.

Beats are related to and distinguished from pulse, rhythm (grouping), and meter:

Meter is the measurement of the number of pulses between more or less regularly recurring accents. Therefore, in order for meter to exist, some of the pulses in a series must be accented—marked for consciousness—relative to others. When pulses are thus counted within a metric context, they are referred to as beats.

— Leonard B. Meyer and Cooper (1960)[3]

Metric levels faster than the beat level are division levels, and slower levels are multiple levels. Beat has always been an important part of music. Some music genres such as funk will in general de-emphasize the beat, while other such as disco emphasize the beat to accompany dance.[4]

Division

[edit]As beats are combined to form measures, each beat is divided into parts. The nature of this combination and division is what determines meter. Music where two beats are combined is in duple meter, music where three beats are combined is in triple meter. Music where the beat is split in two are in simple meter, music where the beat is split in three are called compound meter. Thus, simple duple (2

4, 4

4, etc.), simple triple (3

4), compound duple (6

8), and compound triple (9

8). Divisions which require numbers, tuplets (for example, dividing a quarter note into five equal parts), are irregular divisions and subdivisions. Subdivision begins two levels below the beat level: starting with a quarter note or a dotted quarter note, subdivision begins when the note is divided into sixteenth notes.

Downbeat and upbeat

[edit]

The downbeat is the first beat of the bar, i.e. number 1. The upbeat is the last beat in the previous bar which immediately precedes, and hence anticipates, the downbeat.[5] Both terms correspond to the direction taken by the hand of a conductor.

This idea of directionality of beats is significant when you translate its effect on music. The crusis of a measure or a phrase is a beginning; it propels sound and energy forward, so the sound needs to lift and have forward motion to create a sense of direction. The anacrusis leads to the crusis, but doesn't have the same 'explosion' of sound; it serves as a preparation for the crusis.[6]

An anticipatory note or succession of notes occurring before the first barline of a piece is sometimes referred to as an upbeat figure, section or phrase. Alternative expressions include "pickup" and "anacrusis" (the latter ultimately from Greek ana ["up towards"] and krousis ["strike"/"impact"] through French anacrouse). In English, anákrousis translates literally as "pushing up". The term anacrusis was borrowed from the field of poetry, in which it refers to one or more unstressed extrametrical syllables at the beginning of a line.[5]

On-beat and off-beat

[edit]

In typical Western music 4

4 time, counted as "1 2 3 4, 1 2 3 4...", the first beat of the bar (downbeat) is usually the strongest accent in the melody and the likeliest place for a chord change, the third is the next strongest: these are "on" beats. The second and fourth are weaker—the "off-beats". Subdivisions (like eighth notes) that fall between the pulse beats are even weaker and these, if used frequently in a rhythm, can also make it "off-beat".[9]

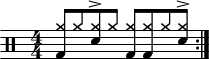

The effect can be easily simulated by evenly and repeatedly counting to four. As a background against which to compare these various rhythms a bass drum strike on the downbeat and a constant eighth note subdivision on ride cymbal have been added, which would be counted as follows (bold denotes a stressed beat):

But one may syncopate that pattern and alternately stress the odd and even beats, respectively:

- 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 — the stress on the "unexpected", or syncopated, beat ⓘ

So "off-beat" is a musical term, commonly applied to syncopation, that emphasizes the weak even beats of a bar, as opposed to the usual on-beat. This is a fundamental technique of African polyrhythm that transferred to popular western music. According to Grove Music, the "Offbeat is [often] where the downbeat is replaced by a rest or is tied over from the preceding bar".[9] The downbeat can never be the off-beat because it is the strongest beat in 4

4 time.[10] Certain genres tend to emphasize the off-beat, where this is a defining characteristic of rock'n'roll and ska music.

Backbeat

[edit]

A back beat, or backbeat, is a syncopated accentuation on the "off" beat. In a simple 4

4 rhythm these are beats 2 and 4.[13]

"A big part of R&B's attraction had to do with the stompin' backbeats that make it so eminently danceable," according to the Encyclopedia of Percussion.[14] An early record with an emphasised back beat throughout was "Good Rockin' Tonight" by Wynonie Harris in 1948.[15] Although drummer Earl Palmer claimed the honor for "The Fat Man" by Fats Domino in 1949, which he played on, saying he adopted it from the final "shout" or "out" chorus common in Dixieland jazz. There is a hand-clapping back beat on "Roll 'Em Pete" by Pete Johnson and Big Joe Turner, recorded in 1938. A distinctive back beat can be heard on "Back Beat Boogie" by Harry James And His Orchestra, recorded in late 1939.[16] Other early recorded examples include the final verse of "Grand Slam" by Benny Goodman in 1942 and some sections of The Glenn Miller Orchestra's "(I've Got A Gal In) Kalamazoo", while amateur direct-to-disc recordings of Charlie Christian jamming at Minton's Playhouse around the same time have a sustained snare-drum backbeat on the hottest choruses.

Outside U.S. popular music, there are early recordings of music with a distinctive backbeat, such as the 1949 recording of Mangaratiba by Luiz Gonzaga in Brazil.[17]

Slap bass executions on the backbeat are found in styles of country western music of the 1930s, and the late 1940s early 1950s music of Hank Williams reflected a return to strong backbeat accentuation as part of the honky tonk style of country.[19] In the mid-1940s "hillbilly" musicians the Delmore Brothers were turning out boogie tunes with a hard driving back beat, such as the No. 2 hit "Freight Train Boogie" in 1946, as well as in other boogie songs they recorded.[citation needed] Similarly Fred Maddox's characteristic backbeat, a slapping bass style, helped drive a rhythm that came to be known as rockabilly, one of the early forms of rock and roll.[20] Maddox had used this style as early as 1937.[21]

In today's popular music the snare drum is typically used to play the backbeat pattern.[7] Early funk music often delayed one of the backbeats by an eighth note so as "to give a 'kick' to the [overall] beat".[18]

Some songs, such as The Beatles' "Please Please Me" and "I Want to Hold Your Hand", The Knack's "Good Girls Don't" and Blondie's cover of The Nerves' "Hanging on the Telephone", employ a double backbeat pattern.[22] In a double backbeat, one of the off beats is played as two eighth notes rather than one quarter note.[22]

Some drummers slightly delay the backbeat on the snare drum to create a more relaxed feel, a technique known as the "delayed" or "late backbeat." In such cases, the intervals between beats 2 and 3, and between beats 4 and 1, are slightly shortened to prevent the tempo from slowing down. This playing style is particularly common in rock and soul music from the late 1960s to the mid-1970s.[23] Notable examples can be heard in recordings such as "Green Onions" by Booker T. & the M.G.'s, "And Your Bird Can Sing" by The Beatles, "Hey Joe" by The Jimi Hendrix Experience, and "Easy" by The Commodores. Drummer Charlie Watts of The Rolling Stones frequently employed this technique during this period, as heard in tracks like "Monkey Man," "Wild Horses," "Sister Morphine," and "Let It Bleed."[24] A delayed backbeat can also be heard in the famous eight-bar "Funky Drummer" break, played by Clyde Stubblefield.[25] Early backbeats can be heard in Bruce Springsteen's "The River," The Police's "Every Breath You Take," and D'Angelo's "The Line."[26]

Cross-beat

[edit]Cross-rhythm. A rhythm in which the regular pattern of accents of the prevailing meter is contradicted by a conflicting pattern and not merely a momentary displacement that leaves the prevailing meter fundamentally unchallenged

Hyperbeat

[edit]

A hyperbeat is one unit of hypermeter, generally a measure. "Hypermeter is meter, with all its inherent characteristics, at the level where measures act as beats."[28][29]

Beat perception

[edit]Beat perception refers to the human ability to extract a periodic time structure from a piece of music.[30][31] This ability is evident in the way people instinctively move their body in time to a musical beat, made possible by a form of sensorimotor synchronization called 'beat-based timing'. This involves identifying the beat of a piece of music and timing the frequency of movements to match it.[32][33][34] Infants across cultures display a rhythmic motor response but it is not until between the ages of 2 years 6 months and 4 years 6 months that they are able to match their movements to the beat of an auditory stimulus.[35][36]

Related concepts

[edit]- Tatum refers to a subdivision of a beat which represents the "time division that most highly coincides with note onsets".[37]

- Afterbeat refers to a percussion style where a strong accent is sounded on the second, third and fourth beats of the bar, following the downbeat.[13]

- In reggae music, the term one drop refers to the complete de-emphasis (to the point of silence) of the first beat in the cycle.

- James Brown's signature funk groove emphasized the downbeat – that is, with heavy emphasis "on the one" (the first beat of every measure) – to etch his distinctive sound, rather than the back beat (familiar to many R&B musicians) which places the emphasis on the second beat.[38][39][40]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Berry, Wallace (1976/1986). Structural Functions in Music, p. 349. ISBN 0-486-25384-8.

- ^ Winold, Allen (1975). "Rhythm in Twentieth-Century Music", Aspects of Twentieth-Century Music, p. 213. With, Gary (ed.). Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice–Hall. ISBN 0-13-049346-5.

- ^ Cooper, Grosvenor and Meyer, Leonard B. Meyer (1960). The Rhythmic Structure of Music, p.3-4. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-11521-6/ISBN 0-226-11522-4.

- ^ Rajakumar, Mohanalakshmi (2012). Hip Hop Dance. ABC-CLIO. p. 5. ISBN 9780313378461. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ a b Dogantan, Mine (2007). "Upbeat". Oxford Music Online. Grove Music Online. Archived from the original on May 16, 2008. Retrieved 2007-02-10.

- ^ Cleland, Kent D. and Dobrea-Grindahl, Mary (2013). Developing Musicianship Through Aural Skills, unpaginated. Routledge. ISBN 9781135173050.

- ^ a b Schroedl, Scott (2001). Play Drums Today Dude!, p. 11. Hal Leonard. ISBN 0-634-02185-0.

- ^ Snyder, Jerry (1999). Jerry Snyder's Guitar School, p. 28. ISBN 0-7390-0260-0.

- ^ a b "Beat: Accentuation. (i) Strong and weak beats". Oxford Music Online. Grove Music Online. 2007. Archived from the original on May 16, 2008. Retrieved 2007-02-10.

- ^ "Off-beat". Oxford Music Online. Grove Music Online. 2007. Archived from the original on May 16, 2008. Retrieved 2007-02-10.

- ^ "Introduction to the 'Chop'", Anger, Darol. Strad (0039–2049); 10/01/2006, Vol. 117 Issue 1398, pp. 72–75.

- ^ Horne, Greg (2004). Beginning Mandolin: The Complete Mandolin Method, p. 61. Alfred. ISBN 9780739034712.

- ^ a b "Backbeat". Oxford Music Online. Grove Music Online. 2007. Archived from the original on May 16, 2008. Retrieved February 10, 2007.

- ^ Beck, John H. (2013). Encyclopedia of Percussion, p. 323. Routledge. ISBN 9781317747680.

- ^ Beck (2013), p. 324.

- ^ "The Ultimate Jazz Archive - Set 17/42", Discogs.com. Accessed August 6, 2014.

- ^ "Mangaratiba - Luiz Gonzaga". YouTube. 8 November 2014. Archived from the original on 2021-12-21.

- ^ a b Mattingly, Rick (2006). All About Drums, p. 104. Hal Leonard. ISBN 1-4234-0818-7.

- ^ Tamlyn, Gary Neville (1998). The Big Beat: Origins and Development of Snare Backbeat and other Accompanimental Rhythms in Rock'n'Roll (Ph.D.). ???. pp. 342–43.

- ^ "Riding the Rails to Stardom - The Maddox Brothers and Rose", NPR News. Accessed August 6, 2014.

- ^ "The Maddox Bros & Rose". Rockabilly Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on 3 July 2011. Retrieved June 29, 2011.

- ^ a b Cateforis, C. (2011). Are We Not New Wave?: Modern Pop at the Turn of the 1980s. University of Michigan Press. pp. 140–41. ISBN 978-0-472-03470-3.

- ^ Davis S. Carter and Ralf von Appen, "Measuring the Myth: Microtiming and Tempo Variability in the Music of the Rolling Stones," Theory & Practice 49–50 (2025), https://tnp.mtsnys.org/vol49-50/carter_von_appen

- ^ Davis S. Carter and Ralf von Appen, "Measuring the Myth: Microtiming and Tempo Variability in the Music of the Rolling Stones," Theory & Practice 49–50 (2025), https://tnp.mtsnys.org/vol49-50/carter_von_appen

- ^ Davis S. Carter and Ralf von Appen, "Measuring the Myth: Microtiming and Tempo Variability in the Music of the Rolling Stones," Theory & Practice 49–50 (2025), https://tnp.mtsnys.org/vol49-50/carter_von_appen

- ^ Davis S. Carter and Ralf von Appen, "Measuring the Myth: Microtiming and Tempo Variability in the Music of the Rolling Stones," Theory & Practice 49–50 (2025), https://tnp.mtsnys.org/vol49-50/carter_von_appen

- ^ New Harvard Dictionary of Music (1986: 216). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- ^ a b Neal, Jocelyn (2000). "Songwriter's Signature, Artist's Imprint: The Metric Structure of a Country Song". In Wolfe, Charles K.; Akenson, James E. (eds.). Country Music Annual 2000. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky. p. 115. ISBN 0-8131-0989-2.

- ^ Also: Rothstein, William (1990). Phrase Rhythm in Tonal Music, pp. 12–13. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0028721910

- ^ Grahn, J. A., & Brett, M. (2007). Rhythm and beat perception in motor areas of the brain. Journal of cognitive neuroscience, 19(5), 893-906.

- ^ Patel, A. D., & Iversen, J. R. (2014). The evolutionary neuroscience of musical beat perception: the Action Simulation for Auditory Prediction (ASAP) hypothesis. Frontiers in systems neuroscience, 8, 57.

- ^ Iversen, J. R. (2016). 21 In the beginning was the beat: evolutionary origins of musical rhythm in humans. In: Hartenberger, R. (Ed.). (2016). The Cambridge companion to percussion. Cambridge University Press. p. 281–295.

- ^ Iversen, J. R., & Balasubramaniam, R. (2016). Synchronization and temporal processing. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 8, 175-180.

- ^ Grahn, J. A. (2012). Neural mechanisms of rhythm perception: current findings and future perspectives. Topics in cognitive science, 4(4), 585-606.

- ^ Nettl, B. (2000). An ethnomusicologist contemplates universals in musical sound and musical culture. In: Wallin, N. L., Merker, B., & Brown, S. (Eds.). (2001). The origins of music. MIT press.

- ^ Zentner, M., & Eerola, T. (2010). Rhythmic engagement with music in infancy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(13), 5768-5773.

- ^ Jehan, Tristan (2005). "3.4.3 Tatum grid". Creating Music By Listening (Ph.D.). MIT. Archived from the original on 2012-11-08. Retrieved 2013-08-01.

- ^ Pareles, Jon (2006-12-25). "James Brown, the 'Godfather of Soul', Dies at 73". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-01-10. According to The New York Times, by the "mid-1960s Brown was producing his own recording sessions. In February 1965, with 'Papa's Got a Brand New Bag,' he decided to shift the beat of his band: from the one-two-three-four backbeat to one-two-three-four. 'I changed from the upbeat to the downbeat,' Mr. Brown said in 1990. 'Simple as that, really.'"

- ^ Gross, T. (1989). "Maceo Parker: The Hardest Working Sideman". Fresh Air. WHYY-FM/National Public Radio. Retrieved January 22, 2007. According to Maceo Parker, Brown's former saxophonist, playing on the downbeat was at first hard for him and took some getting used to. Reflecting back to his early days with Brown's band, Parker reported that he had difficulty in playing "on the one" during solo performances, since he was used to hearing and playing with the accent on the second beat.

- ^ Anisman, Steve (January 1998). "Lessons in listening – Concepts section: Fantasy, Earth Wind & Fire, The Best of Earth Wind & Fire Volume I, Freddie White". Modern Drummer Magazine. pp. 146–152. Retrieved January 21, 2007.

Further reading

[edit]- de Momigny, Jérôme-Joseph (1821). La seule vraie théorie de la musique. Paris.

- Riemann, Hugo (1884). Musikalische Dynamik und Agogik. Hamburg: D. Rahter.

- Lussy, Mathis (1903). L'anacrouse dans la musique moderne. Paris: Heugel.

- Cone, Edward T. (1968). Musical Form and Musical Performance. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-09767-6.