Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Pasig River

View on Wikipedia

| Pasig River | |

|---|---|

Pasig River in Manila in 2019 | |

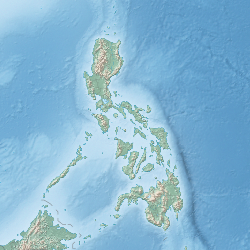

Drainage basin map of the Pasig River | |

Pasig River mouth | |

| |

| Native name | Ilog Pasig (Tagalog) |

| Location | |

| Country | Philippines |

| Region | |

| Cities | |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Laguna de Bay |

| • location | Taguig/Taytay, Rizal |

| • coordinates | 14°31′33″N 121°06′33″E / 14.52583°N 121.10917°E |

| Mouth | Manila Bay |

• location | Manila |

• coordinates | 14°35′40″N 120°57′20″E / 14.59444°N 120.95556°E |

• elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Length | 25.2 km (15.7 mi) |

| Basin size | 4,678 km2 (1,806 sq mi)[2] |

| Width | |

| • average | 90 m (300 ft)[1] |

| Depth | |

| • minimum | 0.5 m (1.6 ft)[1] |

| • maximum | 5.5 m (18 ft)[1] |

| Discharge | |

| • minimum | 12 m3/s (420 cu ft/s)[1] |

| • maximum | 275 m3/s (9,700 cu ft/s)[1] |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left |

|

| • right |

|

| Bridges | 20 |

Pasig summary route map | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Pasig River (Filipino: Ilog Pasig; Spanish: Río Pásig) is a water body in the Philippines that connects Laguna de Bay to Manila Bay. Stretching for 25.2 kilometers (15.7 mi), it bisects the Philippine capital of Manila and its surrounding urban area into northern and southern halves. Its major tributaries are the Marikina River and San Juan River. The total drainage basin of the Pasig River, including the basin of Laguna de Bay, covers 4,678 square kilometers (1,806 sq mi).[2]

The Pasig River is technically a tidal estuary, as the flow direction depends upon the water level difference between Manila Bay and Laguna de Bay. During the dry season, the water level in Laguna de Bay is low with the river's flow direction dependent on the tides. During the wet season, when the water level of Laguna de Bay is high, the flow is reversed towards Manila Bay.

The Pasig River used to be an important transport route and source of water for Spanish Manila. Due to negligence and industrial development, the river suffered a rapid decline in the second half of the 20th century and was declared biologically dead in 1990.[3] Two decades after that declaration, however, a renaturation program designed to revive the river has seen the return of life to the river, including eight fish species, 39 species of birds, and 118 species of trees and other vegetation.[4][5] As a result, the Pasig River received the Asia Riverprize by the International River Foundation in 2019.[3]

The Pasig River Rehabilitation Commission (PRRC) was a Philippine government agency established to oversee rehabilitation efforts for the river from 1999 until it was abolished in November 2019. Rehabilitation efforts are also aided by private sector organizations through raising funds or assisting river cleanups.

Etymology

[edit]The river takes its name from the city of Pasig, which is named after the Tagalog word pasig, meaning "a river that flows into the sea" or "the sandy bank of a river", with the former in reference to the Pasig River's flow from Laguna de Bay towards Manila Bay and out into the South China Sea.[6]

History

[edit]The Pasig River served as an important means of transport; it was Manila's lifeline and center of economic activity. Some of the most prominent kingdoms in early Philippine history, including the kingdoms of Namayan, Maynila, and Tondo grew up along the banks of the river, drawing their life and source of wealth from it. When the Spanish established Manila as the capital of their colonial properties in the Far East, they built the walled city of Intramuros on the southern bank of the Pasig River near its mouth.

-

View of Pasig River 1845

-

View of the Pasig River and the city of Manila with its walls from a northern pueblo. 1789-1794

-

1847 painting by José Honorato Lozano showing a casco barge and sampans traversing the Puente de España bridge (replaced by the Jones Bridge)

-

Pasig River bridge circa 1800s

-

Painting of Pasig River in the 1800s

-

The Pasig River in 1899

-

Casco barges, steamers, and other sailing vessels in Pasig in 1917

-

Aerial view of Fort William McKinley and the Pasig River, c. 1930s

Pollution

[edit]After World War II, massive population growth, infrastructure construction, and the dispersal of economic activities to Manila's suburbs left the river neglected. The banks of the river attracted informal settlers and the remaining factories dumped their wastes into the river, making it effectively a huge sewer system. Industrialization had already polluted the river.[7]

In the 1930s, observers noticed the increasing pollution of the river, as fish migration from Laguna de Bay diminished. People ceased using the river's water for laundering in the 1960s, and ferry transport declined. By the 1970s, the river started to emanate offensive smells, and in the 1980s, fishing in the river was prohibited. In 1990, the Pasig River was considered biologically dead by the Danish International Development Agency.[8][7]

It is estimated that about 60-65 percent of the pollution in the Pasig River comes from household waste disposed into the tributaries of the river. Increasing poverty in the rural areas in Philippines has driven migration to Metro Manila in search of better opportunities. This resulted in rapid urban growth, congestion and overcrowding of land and along the riverbanks, making the river and its tributaries a dumping ground for informal settlers living there. About 30–35 percent of the river pollution is generated from industries located close to the river (such as tanneries, textile mills, food processing plants, distilleries, and chemical and metal plants), some of which do not have water treatment facilities capable of removing heavy metal pollutants. The rest of the pollutants consist of solid waste dumped into the rivers. Metro Manila has been reported to produce as much as 7,000 metric tons (6,900 long tons; 7,700 short tons) of garbage per day.[9] A study conducted by researchers from the Polytechnic University of the Philippines found that the river is also contaminated with microplastics.[10] It is also the world's single largest source of marine plastic pollution, being responsible for 6.43% of global marine plastic pollution.[11]

Rehabilitation efforts

[edit]Efforts to revive the river began in December 1989 with the help of Danish authorities. The Pasig River Rehabilitation Program (PRRP) was established, with the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) as the main agency with the coordination of the Danish International Development Assistance (DANIDA).[12]

In 1994, First Lady Amelita M. Ramos founded the Clean & Green Foundation Inc., a non-government and non-profit organization. The organization conducted fundraising projects such as the Piso para sa Pasig (Filipino: "A peso for the Pasig") campaign. The campaign raised around PHP52 million.[13]

In 1999, President Joseph Estrada signed Executive Order No. 54 establishing the Pasig River Rehabilitation Commission (PRRC) to replace the old PRRP with additional expanded powers such as managing of wastes and resettling of squatters.[12] The PRRC was abolished in November 2019, with its functions and powers being transferred to the Manila Bay Task Force, DENR, Department of Housing and Urban Development, Metropolitan Manila Development Authority (MMDA), and the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH).[14]

In 2010, the television network ABS-CBN and PRRC headed by ABS-CBN Foundation-Bantay Kalikasan Director Gina Lopez – then chairperson of PRRC – launched a fun run fund-raising activity called "Run for the Pasig River" held every October from 2009 to 2013. The proceeds from the fun run will serve as a fund for the "Kapit-bisig para sa Ilog Pasig" (Collaborate for the Pasig River) rehabilitation project of the Pasig River.[15][16][17] No further fun run has been announced since the 2013 event.

In October 2018, the PRRC won the first Asia Riverprize, in recognition of its efforts to rehabilitate the Pasig River.[18][19] According to the PRRC, aquatic life has returned to the river.[18]

On April 20, 2021, San Miguel Corporation announced that it would initiate a clean-up of the Pasig River in May 2021. SMC will also work with the DENR and the DPWH in this river cleanup.[20] The river cleanup is part of San Miguel Corporation's ₱95 billion Pasig River Expressway project.

Pasig River Esplanade

[edit]

On January 17, 2024, the Bongbong Marcos administration inaugurated its Pasig Bigyang Buhay Muli (PBBM; lit. 'Give Life to Pasig Again') project, aiming to revitalize the Pasig River through the development of linear parks, walkways, bikeways, and commercial developments. The program also aims to improve the existing Pasig River Ferry System through the addition of more ferry boats and stations.[21]

Bongbong Marcos inaugurated on January 17, 2024 the "Pasig River Esplanade", the first phase of the P18-billion Pasig River Urban Development of the Rehabilitation of the Pasig River. The Inter-Agency Council for the Pasig River Urban Development (IAC-PRUD) per Jose Acuzar announced that it will build 8 more esplanades in other parts of the 25-kilometer river. The 500-metre (1,600 ft) embankment behind the Manila Central Post Office features the promenade which will be 25 kilometres (16 mi) long on each side of the Pasig River. Acuzar further said that the promenade would lead to a 150-hectare (370-acre) park in Rizal that may be called "Marcos Park".[22][23]

Invasive species

[edit]

The Pasig River has been infested with invasive species, notably the water hyacinth and the janitor fish. Water hyacinth, introduced in the Philippines around 1912 as an ornamental plant, has been thrown into the Pasig River; this led the profusely-growing plants to thrive in the river as well as Laguna de Bay due to shifting tides.[24] The plants are currently considered a notorious pest as they clog the waterways.[25] Introduced in the 1990s to clean algae, the janitor fish has become one of the most destructive fishes. Aside from preying on small fish and contributing to the river's murkiness, its population has exponentially risen due to lack of natural predators.[24]

Memorial

[edit]In December 2024, as memorial to Pasig River, the Philippine Postal Corporation launched at Bonifacio Shrine, Gelo Andres and Renacimiento Manila's work, the P150 "Simbang Gabi sa Ilog Pasig”. The longest usable stamp measures 234mm x 40mm. The postage stamp design features 9 historical churches from Binondo to Antipolo along the River.[26]

Geography

[edit]The Pasig River winds generally northwestward for some 25 kilometers (15.5 mi) from Laguna de Bay, the largest lake in the Philippines, to Manila Bay, in the southern part of the island of Luzon. From the lake, the river runs between Taguig and Taytay, Rizal, before entering Pasig. This portion of the Pasig River, to the confluence with the Marikina River tributary, is known as the Napindan River or Napindan Channel.

From there, the Pasig forms flows through Pasig until its confluence with the Taguig River. From here, it forms the border between Mandaluyong to the north and Makati to the south. The river then sharply turns northeast, where it becomes the border between Mandaluyong and Manila before turning again westward, joining its other major tributary, the San Juan River, and then following a sinuous path through the center of Manila before emptying into Manila Bay.

The whole river and most portions of its tributaries lie entirely within Metro Manila, the metropolitan region of the capital. Isla de Convalecencia, the only island dividing the Pasig River, can be found in Manila and is where the Hospicio de San Jose is located.

Tributaries and canals

[edit]One major river that drains Laguna de Bay is the Taguig River, which enters into Taguig before becoming the Pateros River; it is the border between the municipalities of Pateros and Makati. The Pateros River then enters the confluence where the Napindan Channel and Marikina River meet. The Marikina River is the larger of the two major tributaries of the Pasig River, and it flows southward from the mountains of Rizal and cuts through the Marikina Valley. The San Juan River drains the plateau on which Quezon City stands; its major tributary is Diliman Creek.

Within the city of Manila, various esteros (canals) criss-cross through the city and connect with the Tullahan River in the north and the Parañaque River to the west.

Crossings

[edit]A total of 20 bridges currently cross the Pasig. The first bridge from the source at Laguna de Bay is the Napindan Bridge, followed by the Arsenio Jimenez Bridge to its west. Crossing the Napindan Channel in Pasig is the Bambang Bridge. It is followed by the Kaunlaran Bridge that connects barangays Buting and Sumilang in Pasig.[27]

The next bridge downstream is the C.P. Garcia Bridge carrying C-5 Road and connecting the cities of Makati and Pasig. It is followed by the Sta. Monica–Lawton Bridge, the newest bridge opened in June 2021 that connects Lawton Avenue in Makati to Fairlane Street in Pineda, Pasig as part of the Bonifacio Global City–Ortigas Link Road project approved in 2015.[28]

The Guadalupe Bridge between Makati and Mandaluyong carries Epifanio de los Santos Avenue, the major artery of Metro Manila, as well as the MRT Line 3 from Guadalupe station to Boni station. The Estrella–Pantaleon and Makati–Mandaluyong Bridges likewise connect the two cities downstream, with the latter forming the end of Makati Avenue.

The easternmost crossing in Manila is Lambingan Bridge in the district of Santa Ana. It is then followed by the Tulay Pangarap Footbridge (Abante Bridge), the newest pedestrian bridge that connects the Punta area and Santa Ana proper.[29] It is followed by the Abante Bridge (Tulay Pangarap Footbridge) in Santa Ana, Skyway Stage 3, and the Padre Zamora (Pandacan) Bridge connecting Pandacan and Santa Mesa districts, and carries the southern line of the Philippine National Railways. The expressway bridge of Skyway Stage 3, serving as a connection road between the North Luzon Expressway and the South Luzon Expressway, is built near the mouth of the San Juan River where most parts of it is built and another bridge parallel to Padre Zamora and PNR bridges will be built to merge with NLEX Connector in Santa Mesa; it will thus serve as a solution to heavy traffic along EDSA. The Mabini Bridge (formerly Nagtahan Bridge) provides a crossing for Nagtahan Street, part of C-2 Road. Ayala Bridge carries Ayala Boulevard, and connects the Isla de Convalecencia to both banks of the Pasig.

Further downstream are the Quezon Bridge from Quiapo to Ermita, the Line 1 bridge from Central Terminal station to Carriedo station, MacArthur Bridge from Santa Cruz to Ermita, and the Jones Bridge from Binondo to Ermita. The last bridge near the mouth of the Pasig is the Roxas Bridge (also known as M. Lopez Bridge and formerly called Del Pan Bridge) from San Nicolas to Port Area and Intramuros.

Landmarks

[edit]

The growth of Manila along the banks of the Pasig River has made it a focal point for development and historical events. The foremost landmark on the banks of the river is the walled district of Intramuros, located near the mouth of the river on its southern bank. It was built by the Spanish colonial government in the 16th century. Further upstream is the Hospicio de San Jose, an orphanage located on Pasig's sole island, the Isla de Convalescencia. On the northern bank stands the Quinta Market in Quiapo, Manila's central market, and Malacañan Palace, the official residence of the President of the Philippines. Also on the Pasig River's northern bank and within the Manila district of Sta. Mesa is the main campus of the Polytechnic University of the Philippines.

In Makati, along the southern bank of Pasig, are Circuit Makati (the former Santa Ana Race Track), the Poblacion sewage treatment plant and pumping station of Manila Water, and the Rockwell Center, a high-end office and commercial area. At the confluence of the Pasig and Marikina rivers is the Napindan Hydraulic Control Structure, which regulates the flow of water from the Napindan Channel.

Geographical landmarks

[edit]

The third chapter of Jose Rizal's novel El filibusterismo mentions several stories surrounding certain geographical features along the Pasig River during the Spanish colonial era, such as the Buwayang Bato, the Malapad na Bato, and Doña Geromina's Cave.[30]

Doña Geromina's Cave, according to legend, was built by the Archbishop of Manila as a sanctuary for his former lover.[30] The cave is believed to be located in Barangay Pineda, Pasig under the Bagong Ilog Bridge, which carries Circumferential Road 5 between Pasig and Taguig.[citation needed]

Malapad na Bato

[edit]In what is now Barangay West Rembo, Taguig,[citation needed] a cliff along the river is known as Malapad-na-bato (lit. '"Wide-rock"'), which was considered to be sacred to the early Tagalog people as a home to spirits.[30] After the Nuestra Señora de Gracia Church was completed in 1630, it eventually became a pilgrimage site for newly converted Christians, resulting in a decline in the importance of Malapad-na-bató as a religious site.[citation needed] It was mentioned in El Filibusterismo that the sacred character of the site disappeared as fears of the spirits living there had disappeared after the cliff was inhabited by bandits.[30]

Buwayang Bato

[edit]The Buwayang Bato (lit. '"crocodile rock"') was a rock formation that allegedly resembled a large crocodile. In El Filibusterismo, the legend tells a story of a rich Chinese man who did not believe in Catholicism that boasted of not being afraid of crocodiles. One day, while trading on the river, the man was attacked by a large crocodile. It was said that after the Chinese man prayed to San Nicholas for mercy, the crocodile turned into stone.[30] The rock formation is believed to have been located at the southeastern shore of Mandaluyong, in the namesake barangay of Buayang Bato.[citation needed] Other rock formations in the country that resemble crocodiles can be found near Boracay, and Santa Ana, Cagayan.

Geology

[edit]

The Pasig River's main watershed is concentrated in the plains between Manila Bay and Laguna de Bay. The watershed of the Marikina River tributary mostly occupies the Marikina Valley, which was formed by the Marikina Fault Line. The Manggahan Floodway is an artificially constructed waterway that aims to reduce the flooding in the Marikina Valley during the rainy season, by bringing excess water to Laguna de Bay.

Tidal flows

[edit]The Pasig River is technically considered a tidal estuary. Toward the end of the summer or dry season (April and May), the water level in Laguna de Bay reaches to a minimum of 10.5 meters (34 ft). During times of high tide, the water level in the lake may drop below that of Manila Bay's, resulting in a reverse flow of seawater from the bay into the lake. This results in increased pollution and salinity levels in Laguna de Bay at this time of the year.[31]

Flooding

[edit]The Pasig River is vulnerable to flooding in times of very heavy rainfall, with the Marikina River tributary the main source of the floodwater. The Manggahan Floodway was constructed to divert excess floodwater from the Marikina River into Laguna de Bay, which serves as a temporary reservoir. By design, the Manggahan Floodway is capable of handling 2,400 cubic meters (85,000 cu ft) per second of water flow, with the actual flow being about 2,000 cubic meters (71,000 cu ft) per second. To complement the floodway, the Napindan Hydraulic Control System (NHCS) was built in 1983 at the confluence of the Marikina River and the Napindan Channel to regulate the flow of water between the Pasig River and the lake.[32]

Archaeology

[edit]A human cranium and mandible was described by D. Sánchez y Sánchez (1929) from under 2.1–3 m (6 ft 11 in – 9 ft 10 in) of Pasig River alluvium. It was discovered during construction of the Church of the Jesuits in 1921 and was partially damaged during excavation,[33] and was noted to be 'primitive' through a loss of Neanderthal characters and mandibular traits (most notably in the teeth and lack of chin), coining the name Homo manillensis. Sánchez y Sánchez classified the species as pre-indigenous using outdated methods based on racial classification. The specimen remains undated (although a Quaternary age has been suggested[34]), and Romeo (1979) somewhat equates the skull with Homo sapiens in his description. Sarat Chandra (1930) follows suite of Romeo (1979).[35][36][37]

Gallery

[edit]-

Barge on the Pasig River

-

The Pasig River near Quiapo

-

View from Fort Santiago

-

View from Guadalupe Bridge

-

Boat transportation along the Pasig River

-

Pasig River with Circuit Makati

-

Buildings of Binondo and the Binondo-Intramuros Bridge seen at far right

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "House Bill No. 5641" (PDF). May 7, 2015.

- ^ a b Tuddao Jr., Vicente B. (September 21, 2011). "Water Quality Management in the Context of Basin Management: Water Quality, River Basin Management and Governance Dynamics in the Philippines" (PDF). www.wepa-db.net. Department of Environment and Natural Resources. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 29, 2016. Retrieved April 10, 2017.

- ^ a b "Process of resurrection continues for once-dead Pasig River". April 20, 2019.

- ^ Villamor, Carmelita, et al. (February 2009) "Biodiversity Assessment of Pasig River and Its Tributaries: Ecosystems Approach (Phase One)."Department of Environment and Natural Resources – Ecosystems Research and Development Bureau (DENR-ERDB).

- ^ Senior, Ira Karen Apanay (August 15, 2009). "Pasig river is feeding ground for exotic species, study shows". The Manila Times. Retrieved April 25, 2022 – via PressReader.

- ^ "Pasig City History". www.pasigcity.gov.ph. Retrieved August 14, 2022.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Murphy, Denis; Anana, Ted (2004). "Pasig River Rehabilitation Program". Habitat International Coalition. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007.

- ^ Suh, Kyung-duck; Cruz, Eric C.; Tajima, Yoshimitsu (September 21, 2017). Asian And Pacific Coast 2017 – Proceedings Of The 9th International Conference On Apac 2017. World Scientific. p. 862. ISBN 978-981-323-382-9. Retrieved April 25, 2022.

- ^ Gorme, Joan B.; Maniquiz, Marla C.; Song, Pum; Kim, Lee-Hyung (2010). "The Water Quality of the Pasig River in the City of Manila, Philippines: Current Status, Management and Future Recovery". Environmental Engineering Research. 15 (3): 173–179. Bibcode:2010EnEnR..15..173G. doi:10.4491/eer.2010.15.3.173.

- ^ Deocaris, Chester C.; Allosada, Jayson O.; Ardiente, Lorraine T.; Bitang, Louie Glenn G.; Dulohan, Christine L.; Lapuz, John Kenneth I.; Padilla, Lyra M.; Ramos, Vincent Paulo; Padolina, Jan Bernel P. (January 22, 2019). "Occurrence of microplastic fragments in the Pasig River". H2Open Journal. 2 (1): 92–100. Bibcode:2019H2OJ....2...92D. doi:10.2166/h2oj.2019.001. ISSN 2616-6518.

- ^ Ritchie, Hannah (May 2021). "Where does the plastic in our oceans come from?". Our World in Data.

- ^ a b Santelices, Menchit. "A dying river comes back to life". Philippine Information Agency. Archived from the original on March 16, 2008.

- ^ Lustre, Monjie. "Clean, green and a not-so-secret garden". Philstar.com. Retrieved November 5, 2024.

- ^ Villanueva, Rhodina; Ramirez, Robertzon (November 15, 2019). "Duterte Abolishes Pasig River Rehabilitation Commission". The Philippine Star. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- ^ "Save the Pasig River, sign up and run". The Philippine Star. November 1, 2009. Archived from the original on August 18, 2024. Retrieved August 18, 2024.

- ^ Villena, Glenda (February 22, 2011). "Pasig River run claims Guinness world record". Yahoo Life Singapore. Archived from the original on August 18, 2024. Retrieved August 18, 2024.

- ^ Choa, Kane Errol (October 3, 2013). "Why run for the Pasig River?". The Philippine Star. Archived from the original on August 18, 2024. Retrieved August 18, 2024.

- ^ a b "'Instagrammable?' Restored Pasig River wins international environment award". ABS-CBN News. October 17, 2018. Retrieved October 20, 2018.

- ^ "Pasig River rehabilitation program feted in first Asia RiverPrize awards". GMA News Online. October 17, 2018. Retrieved October 20, 2018.

- ^ "Pasig River cleanup to start in May". CNN Philippines. April 20, 2021. Archived from the original on April 20, 2021. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- ^ "PBBM leads efforts to bring Pasig River back to its old glory through "Pasig Bigyang Buhay Muli" project". Presidential Communications Office. January 17, 2024.

- ^ "Pasig River Esplanade is Manila's latest IG-worthy spot". ABS-CBN News and Current Affairs. February 7, 2024.

- ^ Domingo, Katrina (January 17, 2024). "Initial phase of P18-B Pasig River mixed-use park unveiled to the public". ABS-CBN News and Current Affairs.

- ^ a b Tacio, Henrylito D. (August 11, 2023). "Not out of this world: The danger posed by invasive species". Manila Bulletin. Archived from the original on October 29, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2024.

- ^ Dela Cruz, Raymond Carl (October 7, 2020). "Water hyacinths ground Pasig River Ferry ops". Philippine News Agency. Archived from the original on October 28, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2024.

- ^ Romero, Alexis (December 1, 2024). "PHLPost launches 'world's longest usable' Christmas stamps". The Philippine Star. Retrieved December 1, 2024.

- ^ "Pasig City". Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved February 16, 2015.

- ^ "NEDA Board Approved Projects (Aquino Administration) From June 2010 to June 2017" (PDF). National Economic and Development Authority Official Website. February 28, 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 23, 2017. Retrieved September 6, 2018.

- ^ Calucin, Diann Uvy (July 20, 2023). "Manila LGU inaugurates 'Tulay Pangarap' in Sta. Ana". Manila Bulletin. Retrieved July 22, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e The Reign of Greed by José Rizal. Retrieved August 14, 2022.

- ^ "[Laguna de Bay] Lake Elevation". Laguna Lake Development Authority. Archived from the original on September 2, 2009.

- ^ "Laguna de Bay Masterplan". Laguna Lake Development Authority. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007.

- ^ Obermaier, Hugo (1924). Fossil man in Spain. Internet Archive. New Haven, Pub. for the Hispanic Society of America by the Yale University Press.

- ^ Pérez de Barradas, José (1945). "Estado actual de las investigaciones sobre el hombre fósil". Boletín de la Real Academia de la Historia (in Spanish).

- ^ Romeo, Luigi (January 1, 1979). Ecce Homo! A Lexicon of Man. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 978-90-272-7452-6.

- ^ Roy, Sarat Chandra (1930). Man In India Vol.10.

- ^ Sánchez, Domingo Sánchez y (1921). Un cráneo humano prehistórico de Manila (Filipinas) (in Spanish). Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales.

External links

[edit] Media related to Pasig River at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pasig River at Wikimedia Commons- Philippine Information Agency article on the Pasig River

- Pasig River Rehabilitation Commission

Pasig River

View on GrokipediaEtymology

Name Origins and Linguistic Evolution

The name Pasig derives from the Tagalog term pasig, denoting a "sandy riverbank," which likely described the river's sediment-laden shores and banks as observed by pre-colonial communities along its course.[8] This indigenous linguistic root reflects empirical geographic features rather than abstract notions like swift currents, despite occasional unsubstantiated associations with rapidity in popular accounts.[8] Under Spanish colonial rule, initiated in 1571 with Miguel López de Legazpi's expedition, the river's designation evolved to Río Pasig or El Río Pasig, integrating the native name into Hispanic cartography and administrative records by the late 16th century.[9] Early maps and toponymic studies from this era, such as those documenting Manila's waterways, consistently employed this form to denote the vital artery connecting Laguna de Bay to Manila Bay.[10] Following Philippine independence in 1946, the name standardized as Pasig River in official English and Filipino usage, with negligible regional dialectical variants owing to Tagalog's prevalence in Metro Manila and the absence of significant phonological shifts in adjacent Austronesian languages like Kapampangan.[8] Proposed alternative etymologies, including Sanskrit derivations for a "river linking waters" or Chinese corruptions from mabagsik (implying forcefulness), persist as folk traditions but are dismissed by linguists for lacking proto-language cognates or historical attestation.[8]Geography

Course and Physical Characteristics

The Pasig River stretches approximately 27 kilometers from Laguna de Bay, the largest lake in the Philippines, to Manila Bay in the west, serving as the primary waterway bisecting Metro Manila.[7][11] The river's course passes through the cities of Taguig, Makati, Mandaluyong, Pasig, and Manila, channeling water through densely urbanized areas amid a watershed influenced by seasonal rainfall and upstream lake levels.[4] The waterway maintains an average width of 91 meters, varying between roughly 62 and 120 meters along its length, with depths typically ranging from 0.5 to 5.5 meters and an overall average depth of about 1.3 meters.[7][11][12] As a tidal estuary, the Pasig River exhibits bidirectional flow determined by the hydraulic gradient between Manila Bay and Laguna de Bay, with tides alternating between mixed semi-diurnal and diurnal patterns that produce a generally sluggish current.[13][7] This tidal dominance results in flow reversal for approximately 200 days annually, where water discharges toward Manila Bay under normal conditions but backflows during high lake levels or low tides.[7]Tributaries and Watershed

The Pasig River's primary tributaries include the Marikina River, which originates in the upland areas of Rizal province and contributes the largest volume of freshwater inflow, and the San Juan River, draining urbanized eastern sectors of Metro Manila.[13][2] Additional significant feeders are the Napindan Channel from Laguna de Bay and the Pateros-Taguig River system, alongside approximately 43 minor tributaries concentrated in Manila's low-lying districts.[2] These eastern and southern inputs form the core of the river's upstream network, channeling surface runoff from surrounding highlands and urban catchments. The direct watershed of the Pasig River, encompassing the Marikina-Pasig-San Juan basin, covers roughly 635 km², with about 10% in highly urbanized Metro Manila areas.[14] Indirectly, it integrates the expansive Laguna de Bay basin, totaling over 3,651 km² in watershed area plus 871 km² lake surface, as water from Laguna de Bay's 24 sub-basins flows northward via the Napindan Channel during normal conditions.[15] This extended drainage spans parts of Rizal province, Laguna, and Metro Manila, capturing precipitation from the Sierra Madre foothills and contributing to the river's baseline volume of approximately 6.5 million cubic meters.[7] In regional hydrology, the Pasig functions as a tidal-influenced conduit with variable inflows driven by monsoon patterns; the Marikina River delivers peak discharges exceeding 500 m³/s during wet seasons from June to November, while dry-season flows drop significantly, relying more on Laguna de Bay exchanges and the San Juan River's steady 15% contribution to total volume.[7][14] Bankfull capacities reach 700 m³/s downstream of the San Juan confluence, tapering to 500 m³/s upstream, reflecting the cumulative effects of these feeder systems on water balance without engineered diversions.[14]Bridges, Crossings, and Infrastructure

The Pasig River features over a dozen bridges that primarily support vehicular, pedestrian, and rail crossings, reflecting engineering advancements from colonial-era steel constructions to contemporary elevated structures amid Metro Manila's rapid urbanization.[16] Jones Bridge, completed in 1921 after construction began in 1919, was engineered as a steel structure to accommodate modern vehicular traffic, succeeding the flood-damaged Puente de España from the Spanish colonial period.[17] Quezon Bridge, a steel-arched design erected in 1939, replaced the earlier Puente Colgante suspension bridge, linking Quezon Boulevard in Quiapo to Padre Burgos Street in Ermita and enhancing connectivity between key districts.[18] Post-World War II reconstruction emphasized durable vehicular and pedestrian bridges to handle growing traffic volumes, with additions like Nagtahan Bridge and Mabini Bridge incorporating girder designs for heavier loads.[16] Rail crossings, such as the Pandacan Railroad Bridge, integrate with the national network, though many structures face strain from overloaded usage. Historical ferry services, once vital for crossings before widespread bridging, transitioned to supplementary roles; the modern Pasig River Ferry Service, relaunched in 2007 with air-conditioned vessels for up to 150 passengers, operates intermittently between Manila Bay and Laguna de Bay but sees limited adoption due to competition from road infrastructure.[19][20] Urban density exacerbates congestion on these crossings, with bridges routinely handling peak-hour volumes exceeding capacity, leading to bottlenecks that propagate through adjacent roadways.[21] Maintenance demands are heightened by corrosion from the river's polluted waters and heavy axle loads, necessitating periodic reinforcements as documented in assessments of 17 deteriorated spans along the Pasig and Marikina Rivers.[16] To address these issues, the Pasig River Expressway (PAREX), a proposed 19.37 km six-lane elevated tollway spanning the river's length from Radial Road 10 in Manila to C-5 Road in Taguig, aims to bypass surface-level chokepoints and integrate multimodal features for pedestrians and cyclists, though as of February 2025, it awaits presidential guidance for harmonization with rehabilitation initiatives.[22][23]Landmarks and Urban Integration

The historic walled city of Intramuros occupies the southern bank of the Pasig River near its outlet into Manila Bay, forming a key segment of Manila's central business and cultural core. Directly across on the northern bank lies Malacañang Palace, the official residence of the Philippine president, situated in San Miguel district and overlooking the river, which shapes restricted zoning and security perimeters in adjacent urban zones.[24] Further upstream, the Arroceros Forest Park, Manila's sole remaining pre-colonial forest remnant spanning 2.2 hectares, anchors the southern bank at the base of Quezon Bridge, embedding natural greenery within the city's high-density fabric.[25] To the east, along the river's middle reaches in Pasig and Mandaluyong cities, Ortigas Center emerges as a cluster of over 50 skyscrapers exceeding 20 stories, including office towers and commercial hubs, positioned adjacent to the waterway and integrating vertical urban density with riparian access points.[26] Riverside esplanades and linear parks, such as those flanking Arroceros and extending toward eastern districts, facilitate pedestrian connectivity, blending recreational pathways with the river's role as a bisecting artery through Metro Manila's 25-kilometer urban corridor.[27] This configuration underscores the Pasig's influence on land use, with institutional sites like Malacañang enforcing buffer zones that limit high-rise development on northern stretches while southern and eastern banks host mixed historic and commercial integration.[24]History

Pre-Colonial and Early Settlement

Archaeological surveys around Laguna de Bay, the primary source of the Pasig River, have identified over 120 pre-colonial sites yielding nearly 500,000 artifacts, indicating sustained human habitation from Paleolithic times through the medieval period, with concentrated settlements in areas like Pinagbuhatan in Pasig and Pila from the 10th to 15th centuries CE.[28] These findings include burial goods such as pottery and cremation jars, suggesting organized communities reliant on lacustrine and riverine resources for sustenance and mobility.[28] The Pasig River served as a critical artery for Tagalog polities, linking inland settlements around Laguna de Bay to Manila Bay outlets and enabling trade in goods like agricultural produce and fish, as corroborated by the Laguna Copperplate Inscription dated approximately 900 CE, the earliest documented evidence of such economic and social interactions in the region.[28][4] Communities navigated the waterway using outrigger boats akin to bancas, facilitating fishing—evidenced by the prevalence of lakeshore sites—and the exchange that underpinned kinship ties across dispersed barangays.[29] This pre-colonial reliance on the Pasig established it as a foundational conduit for cultural and economic cohesion among Tagalog groups, with polities exploiting its tidal flow for seasonal resource access prior to European contact in 1521.[4][29]Colonial Period and Commercial Role

The Pasig River became integral to Spanish colonial commerce following the establishment of Manila as the hub of the Manila-Acapulco galleon trade in 1565, providing the primary inland waterway from Manila Bay to the commercial heart of Intramuros. Galleons, prevented from entering the shallow river due to their deep draft of up to 20 feet, anchored in the bay or at Cavite, where goods—primarily Chinese silks, spices, and porcelain destined for New Spain—were lightered via smaller vessels and barges up the Pasig for unloading at riverside wharves.[30] This transshipment process supported the annual galleon voyages until 1815, with the river handling secondary interisland trade in local products like rice and abaca, funneled through quays at the river's mouth.[31] In the late 19th century, Spanish efforts to modernize infrastructure addressed navigational constraints, initiating dredging of the Pasig in 1884 with a steam-powered dredge imported from England, which removed 37,520 cubic meters of mud and sediment by 1887 to accommodate larger steamships.[31] Concurrent port widening projects from 1880 to 1888 constructed dams, deepened channels, and built warehouses near the docks to store exports such as sugar, copra, and hemp, linking the river to emerging rail lines like the 1892 Luzon railway for efficient goods distribution.[31] These developments positioned the Pasig as a conduit for Manila's growing export economy under late Spanish rule. American colonial administration accelerated improvements after 1898, allocating $3 million in 1902 for harbor enhancements that deepened the Pasig's mouth and completed upgrades by 1908, enabling direct access for trans-Pacific steamers and reinforcing the river's role in U.S.-oriented trade.[31] By the early 1900s, with Manila's population surpassing 219,000 as recorded in the 1903 census, the river functioned as a bustling transport artery, ferrying passengers and freight amid rapid urbanization and commercial expansion.[32]Post-Independence Urbanization

Following Philippine independence in 1946 and the devastation of World War II, rural-to-urban migration surged as provincials sought employment opportunities in Manila, swelling the city's population and fostering informal riparian settlements along the Pasig River's banks. This influx contributed to an explosion in urban size, with Metro Manila's density rising from approximately 9,317 persons per square kilometer in 1980 to higher levels in subsequent decades, driven by post-war reconstruction and economic pull factors. Such growth initially strained the river's capacity for waste assimilation and navigation, as shanty developments encroached on flood-prone margins without adequate planning.[33][34] In the 1950s and 1960s, government policies promoted industrial zoning along the Pasig's course, capitalizing on its role as a transport artery for raw materials and goods between Laguna de Bay and Manila Bay, which spurred economic expansion in sectors like manufacturing and heavy industry. Firms in areas like Pasig incorporated during this period, aligning with national efforts to industrialize and boost GDP through export-oriented activities, though this concentrated effluents and infrastructure demands near the waterway. The river's accessibility facilitated such development, yet early overloads on its hydrological limits emerged as settlements and factories proliferated without proportional environmental safeguards.[35][36] By the 1970s, under President Ferdinand Marcos Sr., flood control initiatives addressed urbanization-induced vulnerabilities, including the construction of dikes and canals to regulate Pasig flows and divert excess water from Marikina River tributaries. These measures, part of broader projects like early phases of the Manggahan Floodway system initiated in the decade, aimed to prevent inundation in densely settled areas, with references to dike reinforcements documented in 1976 planning. While enhancing short-term resilience against monsoonal surges, the works reflected reactive adaptation to demographic pressures rather than preventive land-use controls.[37][38]Onset of Severe Pollution (1950s–1990s)

Following World War II, Manila's rapid urbanization and population growth—reaching approximately 1.5 million by the mid-1950s—overwhelmed rudimentary sanitation infrastructure, resulting in massive untreated sewage discharges into the Pasig River that rendered it increasingly unsuitable for bathing and fishing, activities previously integral to local communities.[39] This shift marked the onset of severe degradation, as domestic wastewater, lacking treatment facilities for over 80% of households, directly contaminated the waterway, fostering anaerobic conditions and foul odors by the late 1950s.[33] In the 1970s and 1980s, industrial expansion along the river's banks exacerbated pollution through untreated effluents from factories, while informal squatter settlements, proliferating amid Metro Manila's population surge to over 5 million, contributed direct dumping of household waste and sewage, with daily solid waste inputs estimated at up to 1,500 tons.[40] Livestock operations, including swine and poultry farms in upstream areas, added organic waste loads, amplifying biochemical oxygen demand and causing persistent offensive smells that signaled ecosystem collapse.[41] By 1990, the Philippine Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) officially declared the Pasig River biologically dead, as dissolved oxygen concentrations consistently dropped below 2 mg/L—the threshold for sustaining fish and other aquatic life—driven by a daily biochemical oxygen demand load of 295 tons from domestic (44%) and industrial (45%) sources exceeding the river's assimilative capacity of around 200 tons per day.[13][42] This assessment reflected decades of unchecked anthropogenic pressures, with no viable fish populations remaining.[13]Environmental Condition

Pollution Sources and Causal Factors

The primary sources of pollution in the Pasig River stem from untreated domestic sewage, which accounts for approximately 60% of the total pollutant load, predominantly biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) from household wastewater in densely populated urban areas and informal settlements lacking proper sanitation infrastructure.[43] [44] These discharges occur via direct outfalls and combined sewer systems overwhelmed during heavy rains, with Metro Manila's sewerage coverage remaining below 10% for the population served by the river's watershed, leading to raw effluent rich in organic matter, nutrients, and pathogens entering the waterway untreated.[45] Industrial effluents contribute roughly 33% of the pollution, originating from manufacturing sectors such as textiles, food processing, tanneries, distilleries, chemicals, and metallurgy, which release untreated or partially treated wastewater containing heavy metals, dyes, solvents, and organic compounds directly into the river or its tributaries.[46] [47] These inputs are concentrated along industrial zones bordering the river, where compliance with effluent standards is inconsistent due to aging facilities and economic pressures prioritizing production over treatment. Solid waste dumping adds to the contamination, comprising about 7% of the load, with poverty in upstream communities driving informal disposal of garbage, including plastics, into the river; an estimated 63,000 metric tons of plastic waste flow through the Pasig annually into Manila Bay and the ocean.[43] [48] Underlying causal factors include rapid urbanization without corresponding infrastructure expansion, high population density exceeding sanitation capacity, and regulatory enforcement gaps under Republic Act No. 9275 (the Philippine Clean Water Act of 2004), which requires discharge permits and treatment but suffers from inadequate monitoring, limited penalties, and jurisdictional overlaps that hinder effective implementation by the Department of Environment and Natural Resources.[49] [50] These lapses perpetuate open dumping and bypassing of treatment, as evidenced by persistent high BOD levels despite the law's mandates for pollution abatement from land-based sources.Biological Status and Water Quality Metrics

Water quality monitoring by the Philippine Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) and the Pasig River Rehabilitation Commission (PRRC) has consistently shown elevated fecal coliform levels in the Pasig River, often exceeding 1 million most probable number (MPN) per 100 mL, particularly near urban bridges and discharge points. For instance, measurements at the river outlet recorded ranges from 79,000 to 2,400,000 MPN/100 mL in 2019, with a geometric mean of 350,000 MPN/100 mL, far surpassing the DENR standard of 200 MPN/100 mL for Class C waters suitable for fishing and boating.[51] Recent monitoring through 2024 indicates persistence of these levels in multiple stations, reflecting ongoing untreated sewage inputs despite rehabilitation claims.[52] Biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) levels frequently exceed 30 mg/L, signaling severe organic pollution that depletes dissolved oxygen and impairs aerobic life. This metric, derived from DENR-classified Class D status for the river, correlates with low dissolved oxygen concentrations below 5 mg/L in bottom waters, limiting habitat viability. pH values typically range from 6.5 to 7.5, within neutral bounds but insufficient to offset other contaminants.[53] Heavy metal concentrations, including lead and cadmium, often surpass World Health Organization guidelines for aquatic ecosystems. Sampling has detected lead levels above 0.01 mg/L and cadmium exceeding 0.003 mg/L thresholds in water and sediments, posing bioaccumulation risks.[54] [55] The river's biological status remains degraded, with fish populations absent since the 1990s declaration of biological death due to anoxic conditions and toxin loads. Post-2010 cleanup initiatives have yielded sporadic sightings of migratory species, but no sustained biodiversity recovery is evident, as confirmed by limited fauna in 2008-2009 assessments and ongoing 2024 DENR studies.[56] Plankton and invertebrate communities persist at low diversity, dominated by pollution-tolerant rotifers, underscoring incomplete ecological restoration.Invasive Species and Ecological Disruptions

The Pasig River hosts several invasive species that disrupt native ecosystems through competition, habitat alteration, and resource monopolization. The water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes, synonym Pontederia crassipes), a South American native introduced to the Philippines, has proliferated in the river since at least the 1970s, forming dense floating mats that impede water flow and navigation.[57] These mats block sunlight penetration, suppressing submerged aquatic vegetation and reducing dissolved oxygen availability, which cascades to diminish populations of light-dependent native species and alter food web dynamics via shading and eutrophication enhancement.[58][59] Introduced fish exacerbate these disruptions; Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus), brought for aquaculture in the mid-20th century, dominates through aggressive feeding and reproduction, outcompeting endemic fish for algae and detritus while tolerating hypoxic conditions that exclude less resilient natives.[60][61] Similarly, sailfin catfishes of the genus Pterygoplichthys (locally termed janitor fish), originating from aquarium releases around the early 2000s in connected systems like Laguna de Bay, burrow extensively into sediments—up to 70 cm in length—destabilizing riverbeds, increasing turbidity, and reshaping benthic habitats to favor detritivores over sensitive invertebrates.[62][63] Their air-breathing capability sustains high survival rates in polluted, low-oxygen waters, amplifying proliferation and competitive exclusion of indigenous taxa.[62][63] Management responses prioritize mechanical intervention, with the Pasig River Coordinating and Management Office (PRCMO) and Metropolitan Manila Development Authority conducting regular harvests; for instance, over 1,600 metric tons of water hyacinth and debris were removed in a June 2024 operation spanning the river and tributaries.[64][65] Dredgers and skimmers target infested zones, yet reinfestation persists from nutrient pollution and vegetative fragments drifting downstream.[66][67] Fish control relies on targeted fishing by local communities, but Pterygoplichthys populations remain robust due to rapid maturation and evasion of low-oxygen mortality.[62][63] Overall, these efforts mitigate but do not eradicate disruptions, as underlying eutrophication sustains invader resilience.[59]Flooding, Tidal Dynamics, and Hydrological Risks

The Pasig River, connected to Manila Bay, experiences a mixed semi-diurnal tidal regime that alternates between spring and neap cycles, resulting in bidirectional flow reversals approximately twice daily.[13] These tides propagate upstream, diminishing in amplitude but still inducing water level fluctuations that hinder consistent downstream flow, particularly in the river's middle and upper sections where gravitational drainage is counteracted by ebb and flood phases.[42] The tidal forcing exacerbates stagnation by mixing saline water inland, reducing oxygen transfer efficiency and altering sediment settling patterns, which collectively amplify vulnerability to upstream backups during low freshwater discharge periods.[55] Monsoon-driven flooding poses acute hydrological risks, as intense rainfall overwhelms the river's discharge capacity, leading to rapid bank overflow and inundation of low-lying urban areas. Typhoon Ondoy (international name Ketsana), striking on September 26, 2009, dumped over 450 mm of rain in 24 hours across Metro Manila, causing the Pasig River to breach its banks and contribute to flooding that affected 872,097 residents, resulted in 241 deaths, and submerged extensive riparian zones.[68] [69] Siltation from upstream erosion and anthropogenic sediment loads has progressively narrowed the channel, reducing cross-sectional conveyance and intensifying water level spikes during such events by constraining freeboard.[70] Urban expansion within the watershed has altered hydrological responses through increased impervious surfaces, elevating runoff velocities and peak discharges via reduced infiltration and interception losses. Hydrological simulations indicate that these land-cover shifts heighten flood hydrographs, with empirical analyses linking urbanization to amplified surface runoff contributions that compound tidal backwater effects and elevate overall inundation risks.[71] [72] Combined with tidal dynamics, this results in compounded water level variability, where storm surges interact with neap or spring cycles to prolong high-water stands and extend flood durations.[73]Geology and Archaeology

Geological Formation and Substrate

The Pasig River channel is situated within the Quaternary sedimentary fill of the Manila Basin, a forearc basin formed by ongoing subduction along the Manila Trench, where the South China Sea plate converges beneath the Philippine Mobile Belt at rates of approximately 7-8 cm per year.[74] This tectonic setting has driven basin subsidence since the Pliocene, accommodating thick accumulations of fluvial and deltaic sediments derived from surrounding volcanic and metamorphic terrains.[15] The river's substrate consists predominantly of unconsolidated Holocene alluvial deposits, including sands, silts, gravels, and clays transported via fluvial processes from upstream catchments in the Rizal volcanic highlands and Laguna de Bay basin.[75] These materials overlie Pleistocene units such as the Guadalupe Formation (tuffs and agglomerates) and Taal Tuff, reflecting episodic volcanic contributions from regional andesitic to dacitic eruptions.[15] The fine-grained clay-silt fractions, often interbedded with reworked volcanic ash, form a soft, low-permeability substrate that exhibits high compressibility and susceptibility to erosion under shear stresses from flow or seismic events.[76] Minor fault influences, linked to the broader subduction regime and nearby structures like the Marikina Valley Fault System, have locally deformed the basin fill but do not dominate the river's straight alignment, which instead reflects incision during post-glacial sea-level stabilization around 6,000-10,000 years ago.[15] Deltaic progradation at the Pasig's outlet into Manila Bay has built up layered clinoforms of similar alluvial composition, extending shoreline deposits northward and southward over historical timescales.[75] Overall sedimentation in the substrate reflects Quaternary denudation rates elevated by tectonic uplift in source highlands, with volcanic pyroclastics enhancing depositional volumes.[15]Archaeological Findings and Sites

Excavations in the Santa Ana district along the Pasig River, conducted by the National Museum of the Philippines in the 1960s under archaeologist Robert B. Fox, uncovered a pre-colonial burial ground with over 1,500 pieces of Chinese tradeware ceramics primarily from the Song (960–1279 CE) and Yuan (1271–1368 CE) dynasties.[77][78] These artifacts, including celadon ware and porcelain, were interred alongside local earthenware pottery, iron tools, spindle whorls, and barkcloth beaters in at least 202 graves, evidencing a settled community engaged in long-distance trade with China as early as the 11th century CE.[79] The site's stratigraphy and ceramic typology date the burials to the 13th–15th centuries CE, reflecting the Namayan polity's role as one of the earliest continuous habitations among Pasig River polities.[80] Further evidence of pre-colonial activity emerges from the Arroceros Forest Park site near the river's banks in Manila, where digs have yielded Chinese ceramics, earthenware vessels, and tradeware indicative of trade and possible riverine loading/unloading functions for commodities.[81] This location, proximate to historical rice trading areas, suggests the Pasig facilitated economic exchange in the pre-Hispanic era, with artifacts aligning temporally with 10th–15th century maritime networks linking the Philippines to Southeast Asia and East Asia.[4] Bank excavations along the Pasig have also recovered gold piloncitos—small, bead-like currency units—attesting to localized economic systems predating Spanish contact. Ongoing siltation and pollution, including acidic effluents, pose risks to organic remains and buried artifacts by accelerating corrosion and burial depth increases, complicating future recovery efforts despite the river's designation as a potential national cultural treasure tied to these finds.[82][4]Sedimentation and Long-Term Changes

The Pasig River has experienced progressive sedimentation over decades, driven by both natural geological processes and intensified anthropogenic factors. Upstream deforestation and land degradation in contributing watersheds, particularly accelerating after the 1950s with rapid urbanization and agricultural expansion, have elevated erosion rates and sediment influx.[7] This has reduced the river's average depth to approximately 1.3 meters (ranging from 0.5 to 5.5 meters in recent assessments), compared to historically deeper channels that supported routine navigation.[7] Catastrophic events have episodically amplified long-term deposition. The 1991 Mount Pinatubo eruption deposited pyroclastic sands across the Pasig-Potrero River basin, a key tributary, leading to over 19 years of post-eruption sediment transport equivalent to more than 750 years of pre-eruption yields.[83] Modeling of total suspended solids (TSS) indicates sustained high loads, with peaks exceeding 200 mg/L in dry seasons, contributing to channel infilling and morphological shifts.[84] These cumulative deposits have critically impaired navigability, as elevated sediment concentrations challenge vessel passage and trading routes in downstream reaches toward Manila Bay.[84] Reduced cross-sectional area and storage capacity exacerbate hydrological risks, impeding water flow and amplifying flood peaks during typhoons, with sediments constricting channels and promoting overflow into adjacent urban areas.[85] Historical dredging, documented since the late 19th century in colonial port improvements, aimed to counteract shoaling but has proven insufficient against ongoing inputs without addressing upstream erosion sources.[86]Rehabilitation Initiatives

Early Government Efforts and PRRC (1990s–2010s)

The Philippine government's initial efforts to rehabilitate the Pasig River in the 1990s focused on pollution control and informal settler relocation, spearheaded by the Clean and Green Foundation under former First Lady Amelita Ramos. Launched in the early 1990s, the foundation's initiatives, including the Piso para sa Pasig fundraising campaign started in 1995, aimed to fund cleanup and community programs while evicting and relocating thousands of families from riverbanks to reduce direct waste dumping. By the mid-1990s, these efforts had relocated approximately 5,000 families to areas outside Metro Manila, such as Cavite and Montalban, though challenges persisted due to incomplete enforcement and return migrations.[87][88] In January 1999, President Joseph Estrada established the Pasig River Rehabilitation Commission (PRRC) via Executive Order No. 54 to coordinate multi-agency rehabilitation, building on prior Danish-funded Pasig River Rehabilitation Program (PRRP) pilots from the late 1980s that emphasized waste management and estero dredging. The PRRC oversaw dredging operations that removed over 30 million kilograms of solid waste from the river and tributaries by the 2010s, alongside small-scale wastewater treatment pilots targeting industrial and household effluents. These interventions temporarily elevated dissolved oxygen (DO) levels to around 3 mg/L in segments by the mid-2000s, as monitored annually, but gains were short-lived due to ongoing untreated discharges exceeding the commission's capacity.[89][90][91] Relocation under the PRRC's expanded Clean and Green framework continued, targeting buffer zones along the 27-kilometer waterway and achieving the removal of about 10,000 families by 2008 through partnerships with local governments and housing agencies. However, fecal coliform levels remained above Class C standards (target <5,000 MPN/100mL for recreational use), with reductions falling short of goals due to insufficient sewerage infrastructure and enforcement gaps, as evidenced by persistent high biochemical oxygen demand readings. By the 2010s, the PRRC's efforts had stabilized some ecological metrics but failed to achieve full restoration, prompting its dissolution in November 2019 via Executive Order No. 93 under President Rodrigo Duterte, which cited incomplete objectives and shifted responsibilities to the Department of Environment and Natural Resources.[92][93]Pasig Bigyang Buhay Muli (PBBM) Program Phases

The Pasig Bigyang Buhay Muli (PBBM) program, initiated by President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. in 2022, structures the rehabilitation of the Pasig River through sequential phases focused on developing esplanades, walkways, and integrated urban features along its 25-kilometer stretch.[94] The initiative emphasizes multi-functional design elements, including pedestrian paths, bike lanes, and connections to ferry services, to support transport, recreation, and tourism while linking to broader urban development such as riverside commerce areas.[95][96] Overall completion is targeted for 2027, transforming the waterway into a cohesive public promenade.[94] Phase 1, covering approximately 500 meters behind the Manila Central Post Office, was inaugurated in early 2024 and introduced initial recreational amenities like jogging paths and kiosks as part of the west showcase area.[97][98] This phase laid the groundwork for linear parks and elevated pathways, integrating with historical sites to promote wellness and connectivity.[99] Phase 2, launched in June 2024, extended the esplanade with additional showcase segments, enhancing accessibility and aesthetic features such as fountains and green spaces to foster tourism and daily use.[97][100] Phase 3, opened on February 27, 2025, in Intramuros, targeted historically significant zones like Plaza Mexico to preserve cultural elements while adding rehabilitated areas for public vibrancy and riverfront enhancement.[101] Phase 4, inaugurated on October 19, 2025, at the Lawton Pasig River Ferry Station, spans 530 meters from the Manila Central Post Office to Arroceros Forest Park, incorporating expanded walkways, bike lanes, bridges, and commercial spaces to support economic hubs and commuter links.[6][102][103] This phase aligns with plans for a modern ferry system operational by late 2026, emphasizing seamless integration of transport and urban commerce.[104] The program's design incorporates external funding, such as a $20 million commitment from UAE-based Clean Rivers in February 2025, directed toward waste prevention and supporting rehabilitation efforts without altering core phase structures.[105][106]Relocation Policies and Buffer Zones

The enforcement of a 10-meter easement protection area (EPA) along the Pasig River banks forms a core component of relocation policies, designating these zones as buffers to restrict human encroachment, ensure public safety during floods, and limit direct pollutant inputs from adjacent settlements. Structures within this zone are subject to clearance, with relocation mandated to prevent wastewater, sewage, and solid waste from entering the waterway unfiltered.[107][90] This approach ties directly to pollution abatement by eliminating point-source dumping, as households in the buffer previously contributed untreated effluents via informal connections or open channels.[108] Under Republic Act No. 7279, the Urban Development and Housing Act of 1992, relocation protocols prioritize in-situ upgrades—improving existing sites with infrastructure like water supply and sanitation—to minimize displacement and preserve community ties, but off-site transfers are applied when site conditions preclude upgrades, as in the Pasig's constrained riparian corridors. Off-site moves involve validated informal settler families (ISFs) being resettled to government-provided housing in areas such as Rizal Province or Naic, Cavite, including lots with basic amenities like electricity and livelihood support.[109] The process commences with censuses and inventory tagging to identify eligible households, followed by legal notices and phased evacuations coordinated by agencies like the Housing and Urban Development Coordinating Council (HUDCC) and local units.[108] Initial EPA establishment targeted approximately 10,000 families for relocation starting in the late 1990s, with intensified enforcement since the 2010s addressing persistent encroachments through systematic clearances. Recent implementations, such as the 2025 resettlement of 59-63 households from Manila segments to Cavite sites, exemplify ongoing mechanics, where families receive structured housing units prior to site vacation to comply with anti-eviction safeguards in RA 7279.[108][110][111] These buffers, once cleared, enable maintenance access and ecological restoration, directly curbing the estimated prior contributions of riparian settlements to the river's biochemical oxygen demand loads.[90]Controversies and Criticisms

Debates on Relocation and Informal Settlements

Proponents of relocating informal settlements along the Pasig River argue that these communities serve as major conduits for pollution, with households contributing an estimated 65% of the river's wastewater load through untreated sewage and solid waste dumping prior to clearance efforts.[112][113] Officials from the former Pasig River Rehabilitation Commission (PRRC) have attributed much of the river's degradation to the absence of proper sewerage systems in these settlements, which directly discharge effluents into the waterway.[40] By clearing riverbanks, relocation reduces these entry points, allowing for the enforcement of easement protection areas (EPAs) that buffer the river from future encroachments.[114] Such measures also facilitate infrastructure development, including the creation of linear parks, walkways, and rehabilitation features that were obstructed by dense squatter occupations.[44] Between 1999 and 2018, efforts relocated approximately 18,000 families from high-risk zones, enabling initial renaturation projects that earned international recognition, such as the Asian River Prize.[44] Opponents, including affected communities and advocacy groups, contend that relocations impose severe hardships on urban poor residents who depend on central locations for daily wage labor, vending, and access to markets.[115] Families moved to peripheral sites, such as those in Cavite, often face unemployment due to scarce job opportunities, with former informal economies disrupted and commuting costs rising sharply.[115] Compensation packages, typically valued at around P290,000 for a basic house-and-lot unit, have been criticized for lacking integrated livelihood support or proximity to urban services, rendering them insufficient to offset poverty exacerbation.[115] A recurring concern is the tendency for cleared areas to be reoccupied, either by returning relocatees dissatisfied with distant housing or by new migrants seeking urban access, necessitating sustained monitoring to prevent illegal re-encroachment.[44] Government assessments have noted that without complementary measures like in-situ upgrading or robust enforcement, such recidivism undermines the permanence of gains, as evidenced by persistent squatting pressures along rehabilitated stretches.[116]Assessments of Cleanup Effectiveness

Efforts to remove invasive water hyacinth and floating waste have achieved partial surface-level improvements, with the Department of Environment and Natural Resources-Pasig River Rehabilitation Commission (DENR-PRRC) extracting 1,603.53 tons of mixed solid waste and hyacinth from the river and tributaries between January and May 2024 alone.[117] Similar operations continued into mid-2024, yielding additional tons via targeted clearing in tributaries like the Ilugin River. However, these gains are undermined by persistent high pollution loads, as fecal coliform levels remain critically elevated; for instance, counts reached up to 256 million most probable number per 100 mL (MPN/100 mL) in 2018-2019, exceeding safe thresholds by orders of magnitude (acceptable bathing levels are typically under 1,000 MPN/100 mL). Recent monitoring in connected systems like Laguna Lake tributaries showed geomean fecal coliform ranging from 19 to 1,742 MPN/100 mL in Q2 2024, indicating ongoing fecal contamination that negates surface cleanups.[118] Critics argue that rehabilitation has emphasized visible, short-term measures like debris removal over substantive infrastructure, such as comprehensive sewer systems and wastewater treatment, leading to reversion of gains; for example, 1990s initiatives under the Pasig River Rehabilitation Commission cleared kilometers of blockages and reduced debris but failed to prevent the river's return to biologically dead status within years due to unchecked industrial and domestic effluents.[33][119] Pollution composition data reinforces this, with solid waste comprising only about 10% of inputs, while untreated industrial (45%) and domestic sewage (45%) dominate, highlighting causal gaps in addressing root sources like upstream tributaries where neglect allows continuous inflow of contaminants.[120] In comparison to the River Thames, which transitioned from biologically dead in the 1950s to supporting over 125 fish species by the 1980s through enforced wastewater treatment and industrial regulations over decades, the Pasig has shown slower substantive progress despite similar starting degradation.[121] The Thames' recovery hinged on systemic enforcement and infrastructure scaling to match population pressures, whereas Pasig's persistent high coliform and reversion patterns stem from enforcement lapses and upstream pollution persistence, limiting ecological revival.[122][123]Political Motivations and Resource Allocation

Rehabilitation efforts for the Pasig River have often aligned with presidential tenures, with successive administrations reinitiating or rebranding initiatives to emphasize environmental legacy and urban renewal. Under President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., the Pasig Bigyang Buhay Muli program advanced through phased launches, including Phase 4 on October 19, 2025, which developed 380 meters of walkways, bike lanes, commercial spaces, and bridges as part of a broader P18-billion project.[124] This follows Executive Order No. 92 on August 19, 2025, establishing the Office of the Presidential Adviser on Pasig River Rehabilitation to coordinate agencies, signaling a centralized push amid prior fragmented efforts.[125] Similar patterns occurred under previous leaders: the Pasig River Rehabilitation Commission (PRRC), active from 1999 to 2019, oversaw intermittent progress before dissolution, with restarts under Benigno Aquino III and Rodrigo Duterte tied to electoral visibility rather than sustained implementation.[126] Resource allocation has favored high-profile infrastructure over comprehensive efficiency, with government expenditures supplemented by private contributions but yielding questionable long-term fiscal returns. San Miguel Corporation invested P2 billion in initial cleanup from 2021, removing over 1.3 million tons of waste, as part of its P95-billion Pasig River Expressway project that includes river restoration components.[127][128] Despite public-private partnership (PPP) frameworks enabling such inputs, broader utilization remains limited, as evidenced by ongoing proposals for hybrid PPPs in related ferry systems rather than full-scale adoption across rehabilitation facets.[7] Critics, including policy analysts, argue that allocations prioritize visible promenade developments over addressing upstream pollution sources, potentially inflating costs without proportional governance incentives for maintenance post-handover.[129] Empirical assessments of return on investment highlight minimal quantifiable gains in targeted outcomes like tourism relative to inputs. While the program envisions the river as an economic hub with linear parks and transport links, documented tourism upticks remain negligible, with no peer-reviewed studies confirming revenue surges offsetting the P18-billion scale despite promotional claims of world-class potential.[130] External funding, such as the UAE's $20 million pledge in February 2025, underscores reliance on foreign aid for momentum, yet causal links to sustained economic revival are unproven, raising questions about political motivations favoring short-term optics over verifiable fiscal prudence.[131][129]Current Status and Prospects

Measurable Achievements and Data (Up to 2025)

The Pasig Bigyang Buhay Muli (PBBM) rehabilitation project earned the 2025 Asian Townscape Award from the United Nations, recognizing its advancements in sustainable urban renewal, heritage restoration, and public space development along the river as of October 2025.[132][133] The award highlights measurable infrastructure gains, including expanded esplanades that have improved pedestrian and recreational access.[134] Phase 4 of the PBBM program was launched on October 19, 2025, introducing a 530-meter waterfront segment with continuous esplanades, walkways, bicycle lanes, commercial areas, and bridges from behind the Manila Central Post Office toward Arroceros Forest Park.[135][124] This expansion connects prior phases, creating over 2 kilometers of linear public green spaces by late 2025 and facilitating enhanced urban mobility and flood resilience.[6] The Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) extracted more than 1.6 million kilograms of solid waste from the Pasig River system by June 2024, directly lowering visible debris and pollution inputs through coordinated cleanup operations.[136] Relocation efforts under the broader rehabilitation framework have addressed over 5,000 informal settler families along the riverbanks in 2024, providing housing alternatives to clear buffer zones and reduce encroachment-related waste discharge.[137] Water quality modeling indicates dissolved oxygen levels in rehabilitated segments reaching up to 7.25 mg/L under neap tide conditions, supporting limited aquatic recovery beyond historical lows.[42] Multiple native fish species, including tilapia and catfish, have naturally repopulated cleaner stretches, as verified in biodiversity assessments.[138]Persistent Challenges and Empirical Gaps